- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Guardian book club: Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

There are two schools of thought about Cloud Atlas: the first believes it approaches genius; the second thinks it's too clever by half. When the book reached the US, it did so on a tide of ecstatic publicity. "The reviews have been Messiah-worthy," wrote Tom Bissell in the New York Times. "One critic wrote that the novel makes 'almost everything in contemporary fiction look like a squalid straggle of Nissen huts'." Yet Bissell himself was unconvinced: "This is a book that might very well move things forward. It is also a book that makes one wonder to what end things are being moved."

By the time the novel was nominated for the Man Booker prize , plenty of UK journalists had sharpened their knives, too. "It is one of those flashy rather empty novels," thundered David Robson in the Telegraph, "where the author leaps from setting to setting, narrator to narrator, more concerned with showing off his ventriloquial skills than telling a coherent story."

To an extent, I can see what he means. The book comes in 11 parts, containing six separate narratives, all written in different styles and spanning thousands of years and miles. A summary (I was going to write "brief summary" but the complexity of the book makes that impossible) should give some idea of the scale of Mitchell's ambition – or of the problem, depending on your point of view.

First, we are taken to the mid-19th century and the South Seas, where Adam Ewing, a notary from San Francisco, writes an increasingly unsettling journal of his journey to the remote Chatham Islands and the abusive nature of the hierarchy on his ship.

Second comes a series of high camp letters written by Robert Frobisher to his lover Rufus Sixsmith shortly after the first world war. Frobisher, on the lam from debt and disgrace in England, wheedles his way into the house of famous ageing composer Vyvyan Ayrs, working as his amanuensis and sleeping with his wife on the side.

Third, there is a 1970s Erin Brockovich-style environmental thriller about journalist Louisa Rey's death-defying attempts to get hold of a report written by a scientist (named Rufus Sixsmith) detailing the design problems of a proposed nuclear reactor.

The fourth part takes place in the here and now, following Thomas Cavendish, the 60-year-old owner of a vanity publishing house, who finds himself trapped in an old people's home.

The fifth moves into the future where Somni 451, a genetically engineered "fabricant", answers a series of questions about her "ascension" from a world of ignorance, slavery and dishing up food in an underground fast-food restaurant.

Sixth, we follow a tribesman called Zach'ry through a stone age version of a more distant future, where only a few people carry the guttering flame of civilisation after man's "hunger for more" has "ripped up the skies, boiled up the seas and poisoned the soil".

The first five parts all end in cliffhangers. Only the sixth reaches a conclusion, while also acting as a kind of narrative mirror, since, afterwards, the other narratives are completed in reverse chronological order. They each reach conclusions of their own while feeding into a grand central conceit about the way those desiring power destroy the thing they crave. "The weak are meat the strong do eat," we are told very late in the 11th part of the book – but by that stage we have also already been informed that "winners are the real losers because they learn nothing" and that "rats' nests & rubble is what all belief turns to one day".

As well as these thematic connections, there are other tricksy narrative links. Frobisher discovers Ewing's journal at Ayrs's house (naturally, in two separate halves); Luisa Rey comes across Frobisher's letters as Sixsmith, the nuclear scientist, was their original recipient. She also manages to hear the music Frobisher was working on in Bruges: The Cloud Atlas Sextet. Cavendish receives Luisa Rey's story as a novel sent to his publishing house. Sonmi watches a film of Cavendish's ordeal. Zach'ry's people view Somni as a god, and recordings of her story form one of the few preserved artefacts from the lost civilisation. The main characters all also have comet-shaped birthmarks.

All of which creates the feeling that Mitchell is playing games – especially since he is so keen to remind us that he's one step ahead. Cavendish, for instance, judges the Luisa Rey story just as a cynical reader might: "One or two things will have to go: the insinuation that Luisa Rey is this Robert Frobisher chap reincarnated, for example. Far too hippy-druggy – new age." Someone in the second Somni section also asks: "Didn't you spot the hairline cracks?", before pointing out all the narrative inconsistencies in this "fake adventure story". Mitchell even has the audacity to write his own review. "Revolutionary or gimmicky?" Frobisher demands of his Cloud Atlas Sextet. Eventually, he decides it is good – "an incomparable creation".

I can understand why some might object to such metafictional fooling. But I find it hard to disagree with Frobisher. Cloud Atlas is an incomparable creation, and Mitchell's games just make it all the more fun. Those "ventriloquial skills" that annoyed David Robson had me mesmerised. Each voice is strong and true enough to guarantee that crucial emotional as well as intellectual involvement. It was excruciating to abandon the characters at the various (and invariably brilliant) cliffhangers. They are – whatever Robson may say – coherent, powerful stories, and they add up to an impressive whole.

Finally, in case I haven't convinced you, how about these three quick examples of Mitchell's delicious prose: 1. "My bruises, cuts, muscles & extremities groaned like a courtroom of malcontent litigants." 2. "In the smoky firelight the two old men nodded off like a pair of ancient kings passing the aeons in their tumuli." 3. "What's a reviewer? One who reads quickly, arrogantly, but never wisely." Who could argue with that? Over to you – comments will be most appreciated, as they'll help inform John Mullan's final book club column this month.

- David Mitchell

- Booker prize

- Cloud Atlas

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

Book club Guardian book club: John Mullan meets David Mitchell

Comments (…), most viewed.

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

- The New York Review of Books: recent articles and content from nybooks.com

- The Reader's Catalog and NYR Shop: gifts for readers and NYR merchandise offers

- New York Review Books: news and offers about the books we publish

- I consent to having NYR add my email to their mailing list.

- Hidden Form Source

April 18, 2024

Current Issue

Cloud Atlas’s Theory of Everything

November 2, 2012

Warner Brothers

Larry and Lana Wachowski’s Cloud Atlas

Cloud Atlas , the unlikely new adaptation by Lana and Andy Wachowski and Tom Tykwer of David Mitchell’s ingenious novel, should do well on DVD, a format whose capacity for endless replay will enable viewers to study at leisure the myriad concurrences binding the movie’s half dozen plots. Better yet, the directors should hire their friend the philosopher Ken Wilber to provide expert commentary and spare us from having to hit “pause” and “reverse.”

Ken Wilber? In academic circles, Wilber remains obscure. A sixty-three-year-old autodidact, he is the author of an ambitious effort to reconcile empirical knowledge and mystical experience in an “Integral Theory” of existence. Yet his admirers include not only the alternative-healing guru Deepak Chopra—who has called Wilber “one of the most important pioneers in the field of consciousness”—but also the philosopher Charles Taylor, the theologians Harvey Cox and Michael Lerner, and Bill Clinton. Wilber’s generally lucid treatments of both Western science and Eastern spirituality have earned him favor with a coterie of highly literate seekers for whom the phrase “New Age” is nonetheless suspect. He’s an intellectual’s mystic, short on ecstatic visions and long on exegeses of Habermas (whom he regards, for his perception of “homologous structures” in human individual and social development, as something of a kindred spirit). At the Integral Institute, a Colorado-based think tank inspired by Wilber’s ideas, scholars like Jack Crittenden, a professor of political theory at Arizona State University, strive to apply his approach to “global-scale problems,” from climate change to religious conflict.

All of which makes Wilber a natural ally of the Wachowski siblings, whose films tend to reflect a similar grandiosity of ambition. In 2004, Wilber was one of two thinkers—the other was Cornel West—that they invited to deliver a “philosophers’ commentary” on a DVD edition of the Matrix trilogy, their brainy sci-fi masterwork. In Wilber’s take, the movies’ ostensibly Manichean premise—good humans and evil machines duking it out on an illusory electronic terrain—conceals a sophisticated philosophical allegory about a fallen world groping toward enlightenment. He is particularly taken with the trilogy’s concluding minutes, in which Neo, the hacker hero, willingly succumbs to Agent Smith, his digital nemesis, and both dissolve into streams of light. This final twist, Wilber contends, is a sign that the necessary “reintegration” of body (humans), mind (the matrix), and spirit (machines) is underway, not to mention proof of an unusually developed directorial consciousness. “To think they had the nerve to put that stuff into a commercial blockbuster like this is an absolutely rare deed!” he exclaims at one point.

kenwilber.com

In their Matrix commentary, Wilber and West name-checked most of philosophy’s leading lights, from Plato and Descartes to Schopenhauer, Emerson, and the ancient Hindu authors of the Upanishads. A similar list of influences on Cloud Atlas would surely include Wilber’s own name somewhere near the top. The film, which runs to nearly three hours and careers through time, places, genres, and storylines, relying on a small ensemble of big-ticket actors to play as many as six roles each, has largely baffled critics . Manohla Dargis, of The New York Times , called it a “megabucks hash of time, space, and cinema” that “weaves together multiple stories through a lot of airy cosmic convenience and a cavalcade of false noses.” Much of the bewilderment may be explained by the Wachowskis’ philosophical predilections; their movie appears to owe as much to Wilber’s brand of cerebral mysticism as to Mitchell’s fiction, a circumstance that, at least with respect to box-office revenue, is likely to be a disadvantage.

Cloud Atlas the novel is a marvel, a singular parable about the human race’s dueling capacities for self-annihilation and survival comprised of six disparate sections, sliced and shuffled, as in a card trick, to yield a suggestively resonant whole. The strands include an American notary’s maritime diary of a voyage through the South Pacific in the 1840s; the letters of a dissolute musical prodigy in pre-war rural Belgium; the final testimony of a genetically engineered fast-food worker awaiting execution in a twenty-second-century police state; and the oral epic of a goatherd living hand-to-mouth on a Hawaiian island in a distant, post-apocalyptic future, a place where English has devolved into a memorably salty pidgin. (“I’d got diresome hole-spew that day ‘cos I’d ate a gammy dog leg in Honokaa….”) Mitchell’s fecund imagination and skill as a ventriloquist have been amply noted ; the novel’s six narrators are utterly distinct yet equally eloquent.

The virtuosity extends to the book’s Russian doll construction: each section becomes a text that is read—or, in one case, a film that is viewed—by a character in the succeeding one. Thus Robert Frobisher, the musical prodigy, is entranced by the diary of Adam Ewing, the seafaring notary, which he discovers in his room at the Belgian chateau belonging to the syphilitic composer to whom he is serving as amanuensis. In turn, Frobisher’s letters preoccupy Luisa Rey, the heroine of the third section, an intrepid reporter in 1970s southern California intent on exposing a corrupt oil company. Rey retrieves Frobisher’s letters from a hotel room where his lover, now an aging nuclear scientist, was murdered. Then, in the fourth section, Rey’s saga arrives as a manuscript submission by an aspiring crime-thriller writer in the mailbox of Timothy Cavendish, a hack publisher in contemporary London. And so on.

Other mysterious bonds connect the sections, including a comet-shaped birthmark shared by five protagonists, men and women both, living hundreds of years apart. The reader encounters all but one of the sections twice, first in chronological order, and then, after the sixth section, in reverse, so that the novel collapses in on itself like a folding telescope, ending where it began, with Adam Ewing’s diary, in the 1840s.

Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory, elaborated over the course of thirty-five years and in more than twenty densely argued books, features a similar nested design. In simplified form, it says something like this: reality is composed exclusively of holons , a term borrowed from Arthur Koestler to denote that which is simultaneously an autonomous whole and a part of something larger. Just as a brain cell is both a self-contained unit and part of a larger organ, so, too, a human being exists as a single individual and as part of a larger collective—a family, an ethnic group, the human race, all living things—in a pattern that extends indefinitely in both directions. It’s holons all the way up and all the way down.

According to Wilber, even consciousness evolves in holarchical fashion, so that the “amount of consciousness” in any given holon is greater than that of its constituents, which it incorporates and transcends, yielding distinctive new forms. He is less interested in definitions—as he points out, there’s no consensus about what consciousness is, let alone which life forms have it—than in the grand pattern. “It really does not matter, as far as I’m concerned, how far down (or not) you wish to push consciousness,” he writes in Sex, Ecology, Spirituality . “The important point…is simply that each new and emergent interior holon transcends but includes, and thus operates upon, the information presented by its junior holons, and thus it fashions something novel in the ongoing cognitive or interior stream.”

Wilber is an ecumenical taxonomist; he doesn’t choose between materialist and idealist accounts of consciousness. Competing schools of knowledge, he suggests, merely reflect limitations of perspective, a problem that conveniently disappears once all more or less plausible points of view are properly integrated, “not on the level of details—that is finitely impossible; but on the level of orienting generalizations.” He is big on labels and diagrams. No doubt part of his appeal is a talent for reducing complex phenomena to a flowchart. Who wouldn’t want a map of reality that fits in a wallet?

www.kheper.net

A diagram elaborated by Wilber to explain Integral Theory

In his schema, the highest form of consciousness is “transpersonal,” a state in which identification with the divine unity (“World Soul”) underlying all things is possible, if rarely achieved. Wilber, who is not known for intellectual modesty, told the science writer John Horgan that he can sustain this “nondual” awareness in deep sleep, something he claimed not even the Dalai Lama can do. But even as we take baby steps toward enlightenment, human history is stuck on endless repeat. “The mystics are pretty sure about this,” Wilber told Horgan. “This has happened a gazillion times; it’ll happen another gazillion.”

With Lana Wachowski, Wilber apparently established an instant rapport. “You and I both are, you know, we’re integrally informed,” he remarks during a 2004 conversation with Lana—who is transgender and was then called Larry—according to a transcript posted on Wilber’s website. “You’ve been interested in this as long as I have, in terms of, you know, the span of your adult life. When you and I first talked on the phone…we spent three and a half hours, and it was non-stop talking about all these things.” Larry confirms Wilber’s account—“it was like one of those great moments where you meet someone, and you talk, and you have a confirmation or a validation about the world”—and tells him that she and her father are reading Sex, Ecology, Spirituality together.

Two years later, in a giddy blog post about the New York premier of V for Vendetta , which Wilber attended at the Wachowskis’ invitation (the siblings wrote the screenplay), he describes Larry as among the “most brilliant minds that I have jumped into a dance of intersubjectivity with,” adding,

Larry will begin a single sentence with a quote from the Upanishads and Schopenhauer, weave it through different interpretations of Chekhov and Tolstoy, and end up—in the same sentence, mind you—with their relationship to recent digital video games. I have honestly never seen anything like it.

(Wilber, who is apparently not so enlightened that he is immune to the ego-trip of the red carpet, also gives a breathless account of his limo ride, his encounter with John Hurt, and his date’s Alexander McQueen gown, in which she “outshone even Natalie Portman.”)

The Wachowskis are notoriously press-shy. One of their few explicit statements regarding their intellectual vision for Cloud Atlas is in a YouTube trailer , online since July, in which they and Tykwer invoke themes of “connectedness and karma,” while admitting that the movie is “hard to sell because it is hard to describe.” But their decision to have the same actors play characters in different storylines, and to shuttle among all the plots at once, is telling. With these gestures, the directors made literal what Mitchell had left playfully ambiguous: characters in later sections are the spiritual embodiments—reincarnations—of those in earlier ones.

Cloud Atlas

Thus, in the movie, Luisa Rey (Halle Berry), doesn’t just share a birthmark with Robert Frobisher, the musical prodigy; as Jocasta, the bored young wife of the aged composer Frobisher works for, Berry actually sleeps with him—and so, by the power of transitivity, does Rey. The bad karma racked up by characters Tom Hanks plays in earlier storylines, including a quack doctor who tries to poison Adam Ewing in order to rob him, is more than compensated for centuries later by Hanks’ heroic behavior as Zachry, the goatherd, who undertakes to save what’s left of the human race from certain self-destruction. (Got that?)

Characters with and without birthmarks are captured, enslaved, liberated, and transformed, and the actors who play them cross ethnic and gender as well as temporal barriers. The Korean actress Doona Bae plays both Sonmi-451, the futuristic fast-food drone, and, with far less conviction, Adam Ewing’s red-haired San Franciscan wife. Viewers are asked to take all this in while absorbing a steady stream of heady apercus—“From womb to tomb we are bound to others; with each crime and every kindness, we birth our future”—and hurtling between sets whose lavish detail far exceeds the requirements of plot and which are evidently intended as tributes to entire cinematic genres, including noir, anime, and Merchant-Ivory.

During the film’s opening sequence, as we are whisked through half a dozen scenes, each in medias res and taking place decades and sometimes centuries apart, Timothy Cavendish (the delightful Jim Broadbent) pleads forbearance: “If you extend your patience for just a moment, there is a method to this tale of madness.” Surely he’s right, and that’s part of the problem. So intent are the Wachowskis and Tykwer on delivering the movie’s mystical tidings—we’re not just bodies, but also souls (or even holons); the choices we make in one life affect who we become in another; we’re all connected to each other and to something bigger than ourselves—that the film risks the earnest impenetrability of a New Age infomercial.

It’s easy to see how Mitchell’s novel, with its nested construction, mysterious concordances, and perpetually recurring birthmark, could give off a Wilberite allure. And to be fair, Mitchell gave the film script his blessing (though he has also told reporters that he considered his book “unfilmable.”) Yet where the filmmakers evangelize, Mitchell treads lightly, with a mischievous wink. For every implied connection between two characters across time and space, another character pooh-poohs the very notion. As Timothy Cavendish, the London publisher, says when he accepts “Half-Lives: the First Luisa Rey Mystery” for publication:

One or two things will have to go: the insinuation that Luisa Rey is this Robert Frobisher chap reincarnated, for example. Far too hippie-druggy-new age. (I too have a birthmark below my left armpit, but no lover ever compared it to a comet.)

And, of course, as Mitchell reminds us, “Half-Lives,” like the novel’s other sections, is a work of fiction, not to be confused with truth.

Mitchell has said that he doesn’t believe in reincarnation , at least not for human beings. (He told an interviewer that he intended the birthmark as a symbol of “the universality of human nature.” ) In his fiction, however, the same names tend to recur from one book to the next. In his first novel, Ghostwritten , Luisa Rey makes a brief appearance as a true-crime writer who calls in to a late-night radio show. Her name is itself an homage to a work of fiction: Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey , another imaginative exploration of the metaphysical bond connecting a seemingly random group of people. In that novel, a lonely society matron veers between despair that “the world had no plan in it” and a flicker of belief in what Wilder eloquently terms “the great Perhaps.” Belief in the great Perhaps suffuses Cloud Atlas the novel; the misstep of Cloud Atlas the film is to try to turn Perhaps into Certainty.

Subscribe to our Newsletters

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

More by Emily Eakin

January 23, 2017

March 25, 2013

July 27, 2012

Emily Eakin has worked as a senior editor at The New Yorker and as a culture reporter at The New York Times .

Short Review

July 20, 1972 issue

April Films to Watch at Home

J. Hoberman’s monthly film roundup, usually a selection of what to see in theaters, now offers films that can be streamed online while readers are staying at home because of the pandemic.

April 4, 2020

Leonard Schapiro (1908–1983)

December 22, 1983 issue

The Current Cinema

December 11, 1975 issue

From ‘The Lady Eve’

December 20, 1990 issue

A Virtual Summer: Films to Stream

More virtual summer is provided by the Criterion Channel, which is streaming its comprehensive collection of Olympic films from Stockholm 1912 to London 2012.

August 11, 2020

Easter 2020: The Eighth Sacrament

Happy Easter, in spite of the coronavirus pandemic, from the Review.

April 12, 2020

Philosophy as a Humanist Discipline: The Legacy of Isaiah Berlin, Stuart Hampshire, and Bernard Williams

On June 22, 2013, The New York Review held a conference to celebrate its fiftieth anniversary and to honor the lives, work, and legacy of Isaiah Berlin, Stuart Hampshire and Bernard Williams. We are pleased to present an audio record of this event.

August 15, 2013

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

CLOUD ATLAS

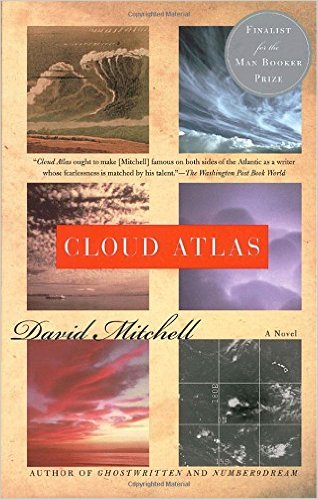

by David Mitchell ‧ RELEASE DATE: Aug. 24, 2004

Sheer storytelling brilliance. Mitchell really is his generation’s Pynchon.

Great Britain’s answer to Thomas Pynchon outdoes himself with this maddeningly intricate, improbably entertaining successor to Ghostwritten (2000) and Number9Dream (2002).

Mitchell’s latest consists of six narratives set in the historical and recent pasts and imagined futures, all interconnected whenever a later narrator encounters and absorbs the story that preceded his own. In the first, it’s 1850 and American lawyer-adventurer Adam Ewing is exploring endangered primitive Pacific cultures (specifically, the Chatham Islands’ native Moriori besieged by numerically superior Maori). In the second, “The Pacific Diary of Adam Ewing” falls (in 1931) into the hands of bisexual musician Robert Frobisher, who describes in letters to his collegiate lover Rufus Sixsmith his work as amanuensis to retired and blind Belgian composer Vivian Ayrs. Next, in 1975, sixtysomething Rufus is a nuclear scientist who opposes a powerful corporation’s cover-up of the existence of an unsafe nuclear reactor: a story investigated by crusading reporter Luisa Rey. The fourth story (set in the 1980s) is Luisa’s, told in a pulp potboiler submitted to vanity publisher Timothy Cavendish, who soon finds himself effectively imprisoned in a sinister old age home. Mitchell then moves to an indefinite future Korea, in which cloned “fabricants” serve as slaves to privileged “purebloods”—and fabricant Sonmi-451 enlists in a rebellion against her masters. The sixth story, told in its entirety before the novel doubles back and completes the preceding five (in reverse order), occurs in a farther future time, when Sonmi is a deity worshipped by peaceful “Valleymen”—one of whom, goatherd Zachry Bailey, relates the epic tale of his people’s war with their oppressors, the murderous Kona tribe. Each of the six stories invents a world, and virtually invents a language to describe it, none more stunningly than does Zachry’s narrative (“Sloosha’s Crossin’ and Ev’rythin’ After”). Thus, in one of the most imaginative and rewarding novels in recent memory, the author unforgettably explores issues of exploitation, tyranny, slavery, and genocide.

Pub Date: Aug. 24, 2004

ISBN: 0-375-50725-6

Page Count: 496

Publisher: Random House

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: May 15, 2004

LITERARY FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by David Mitchell

BOOK REVIEW

by David Mitchell

by Naoki Higashida ; translated by KA Yoshida & David Mitchell

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

THE MOST FUN WE EVER HAD

by Claire Lombardo ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 25, 2019

Characters flip between bottomless self-regard and pitiless self-loathing while, as late as the second-to-last chapter, yet...

Four Chicago sisters anchor a sharp, sly family story of feminine guile and guilt.

Newcomer Lombardo brews all seven deadly sins into a fun and brimming tale of an unapologetically bougie couple and their unruly daughters. In the opening scene, Liza Sorenson, daughter No. 3, flirts with a groomsman at her sister’s wedding. “There’s four of you?” he asked. “What’s that like?” Her retort: “It’s a vast hormonal hellscape. A marathon of instability and hair products.” Thus begins a story bristling with a particular kind of female intel. When Wendy, the oldest, sets her sights on a mate, she “made sure she left her mark throughout his house—soy milk in the fridge, box of tampons under the sink, surreptitious spritzes of her Bulgari musk on the sheets.” Turbulent Wendy is the novel’s best character, exuding a delectable bratty-ness. The parents—Marilyn, all pluck and busy optimism, and David, a genial family doctor—strike their offspring as impossibly happy. Lombardo levels this vision by interspersing chapters of the Sorenson parents’ early lean times with chapters about their daughters’ wobbly forays into adulthood. The central story unfurls over a single event-choked year, begun by Wendy, who unlatches a closed adoption and springs on her family the boy her stuffy married sister, Violet, gave away 15 years earlier. (The sisters improbably kept David and Marilyn clueless with a phony study-abroad scheme.) Into this churn, Lombardo adds cancer, infidelity, a heart attack, another unplanned pregnancy, a stillbirth, and an office crush for David. Meanwhile, youngest daughter Grace perpetrates a whopper, and “every day the lie was growing like mold, furring her judgment.” The writing here is silky, if occasionally overwrought. Still, the deft touches—a neighborhood fundraiser for a Little Free Library, a Twilight character as erotic touchstone—delight. The class calibrations are divine even as the utter apolitical whiteness of the Sorenson world becomes hard to fathom.

Pub Date: June 25, 2019

ISBN: 978-0-385-54425-2

Page Count: 544

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: March 3, 2019

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 15, 2019

LITERARY FICTION | FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP

HOUSE OF LEAVES

by Mark Z. Danielewski ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 6, 2000

The story's very ambiguity steadily feeds its mysteriousness and power, and Danielewski's mastery of postmodernist and...

An amazingly intricate and ambitious first novel - ten years in the making - that puts an engrossing new spin on the traditional haunted-house tale.

Texts within texts, preceded by intriguing introductory material and followed by 150 pages of appendices and related "documents" and photographs, tell the story of a mysterious old house in a Virginia suburb inhabited by esteemed photographer-filmmaker Will Navidson, his companion Karen Green (an ex-fashion model), and their young children Daisy and Chad. The record of their experiences therein is preserved in Will's film The Davidson Record - which is the subject of an unpublished manuscript left behind by a (possibly insane) old man, Frank Zampano - which falls into the possession of Johnny Truant, a drifter who has survived an abusive childhood and the perverse possessiveness of his mad mother (who is institutionalized). As Johnny reads Zampano's manuscript, he adds his own (autobiographical) annotations to the scholarly ones that already adorn and clutter the text (a trick perhaps influenced by David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest ) - and begins experiencing panic attacks and episodes of disorientation that echo with ominous precision the content of Davidson's film (their house's interior proves, "impossibly," to be larger than its exterior; previously unnoticed doors and corridors extend inward inexplicably, and swallow up or traumatize all who dare to "explore" their recesses). Danielewski skillfully manipulates the reader's expectations and fears, employing ingeniously skewed typography, and throwing out hints that the house's apparent malevolence may be related to the history of the Jamestown colony, or to Davidson's Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a dying Vietnamese child stalked by a waiting vulture. Or, as "some critics [have suggested,] the house's mutations reflect the psychology of anyone who enters it."

Pub Date: March 6, 2000

ISBN: 0-375-70376-4

Page Count: 704

Publisher: Pantheon

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 2000

More by Mark Z. Danielewski

by Mark Z. Danielewski

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Anthony Doerr’s Optimism Engine

By James Wood

A curious coincidence, of the kind favored by certain novelists, occurred in 2014 and 2015, when both the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and the Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction were awarded in consecutive years to Donna Tartt, for “ The Goldfinch ,” and Anthony Doerr, for “ All the Light We Cannot See .” These novels, enormous best-sellers, are essentially children’s tales for grownups, and feature teen-age protagonists. In both books, the teen-ager possesses a rare object that has been removed from a great museum; the subsequent adventures of the object are inextricable from the adventures of the protagonist. In “ The Goldfinch ,” the object is an exquisite seventeenth-century painting, which thirteen-year-old Theo Decker has stolen from the Metropolitan Museum. In “All the Light We Cannot See,” Marie-Laure LeBlanc, sixteen years old and blind, ends up as the surviving guardian of a hundred-and-thirty-three-carat diamond known as the Sea of Flames, which once sat in a vault in the Museum of Natural History in Paris. As the Nazis closed in on the city, Marie-Laure and her father, who worked at the museum, fled with the gem to Saint-Malo.

The two novels end with loudly redemptive messages. On the final page of Tartt’s book, Theo informs us, “Whatever teaches us to talk to ourselves is important: whatever teaches us to sing ourselves out of despair. But the painting has also taught me that we can speak to each other across time.” Toward the end of Doerr’s novel, a character reflects that to behold young Marie-Laure, who has survived the Second World War, albeit orphaned, “is to believe once more that goodness, more than anything else, is what lasts.” Years later, in 2014, a now elderly Marie-Laure sits in the Jardin des Plantes, and feels that the air is “a library and the record of every life lived.” At each moment, she laments, someone who once remembered the war is dying. But there is hope: “We rise again in the grass. In the flowers. In songs.”

For both writers, I think, the real treasure to be safeguarded is not a particular painting or jewel but story itself: Tartt’s novel shares its very title with the painting in question, and more important to Marie-Laure than the gem are Jules Verne’s adventure stories, which she carries with her throughout the novel; in a stirringly implausible episode, a German soldier is kept alive by listening to her radio broadcast of “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.” In both books, “goodness” is really just the presumed great good of story. We “sing” across the generations, and this song is first of all the novel we hold in our hands, and more generally storytelling itself. This is what lasts, or so these writers hope: history as an enormous optimistic library.

What was implicit in “All the Light We Cannot See” is blaringly overt in Doerr’s new novel, “ Cloud Cuckoo Land ” (Scribner). Scattered across six hundred and twenty or so pages are five stories, set in very different places and periods. In the nearish future, Konstance, a teen-age girl (here’s our hero-guardian, once again), is flying in a spaceship with eighty-five other people, toward a planet that may sustain human life, after its collapse on earth. (Reaching its destination will take almost six hundred years.) In mid-fifteenth-century Constantinople, Anna, a Greek Christian, awaits the assault that has long been threatened by Muslim forces. A few hundred miles away, Omeir, a gentle country boy, finds himself caught up in the Sultan’s army and its march toward Constantinople, and he eventually encounters Anna. In contemporary Lakeport, Idaho, a sweet-natured octogenarian named Zeno Ninis is minding a group of schoolchildren, who are rehearsing a play in the local library, while, outside the building, a troubled ecoterrorist named Seymour sits in his car, a bomb in his lap, about to make his great explosive statement.

These characters are explicitly connected by a fable (or fragments of a fable) that Doerr has invented, and that he attributes to an actual Greek writer, Antonius Diogenes, thought to have flourished in the second century C.E. Titled “Cloud Cuckoo Land,” the Doerr-Diogenes fabrication tells the tale of Aethon, a shepherd who tries to travel to “a utopian city in the sky,” a place in the clouds “where all needs are met and no one suffers.” After assorted escapades of a classical nature—the hero is turned into a donkey and a crow—Aethon returns to earth, grateful for “the green beauty of the broken world,” or, as Doerr capitalizes for the slow-witted, “ WHAT YOU ALREADY HAVE IS BETTER THAN WHAT YOU SO DESPERATELY SEEK. ”

Each of the novel’s five principal characters finds his or her way to this invented Greek text. Anna stumbles across a frail, goatskin codex of the tale in a ruined library in Constantinople. Omeir and Anna eventually fall in love and have children, and together they guard and tend the magical manuscript. Zeno spends his later years translating the Greek fable—indeed, it’s his dramatic version of “Cloud Cuckoo Land” that the schoolchildren are rehearsing in the Idaho library. Konstance’s father, one of a small number of people on the spaceship old enough to remember life on earth (most have been born on board), used to tell embellished adaptations of the Greek story to his daughter at bedtime. Near the end of Doerr’s novel, Diogenes’ fragments reach even Seymour, now in the Idaho State Correctional Institution, where he is doing time for the deadly incident at the library: Seymour gets interested in Zeno’s translation, and asks one of his victims, the town’s former librarian, to send it to him. As he reads, the potent text emits its healing gas. “By age seventeen he’d convinced himself that every human he saw was a parasite, captive to the dictates of consumption,” we’re told. “But as he reconstructs Zeno’s translation, he realizes that the truth is infinitely more complicated, that we are all beautiful even as we are all part of the problem, and that to be a part of the problem is to be human.”

What on earth—or even on Cloud Cuckoo Land—is this? It’s less a novel than a big therapeutic contraption, moving with sincere deliberation toward millions of eager readers. The author might reply, with some justice, that a fable is a therapeutic contraption, and so is plenty of Dickens. Doerr’s new novel, though, is more of a contraption, and more earnestly therapeutic, than any adult fiction I can recall reading. The obsessive connectivity resembles a kind of novelistic online search, each new link unfolding inescapably from its predecessor, as our author keeps pressing Return. The title shared by the Greek text and the novel comes, an epigraph reminds us, from Aristophanes’ comedy “The Birds.” Yet these characters are also bound to one another by larger ropes of classical allusion and cross-reference. Anna and Zeno both excitedly discover the Odyssey before they encounter the Diogenes text; Seymour, who appears to be somewhat autistic, develops a relationship with an owl, which he nicknames Trustyfriend (a borrowing from “The Birds”); when Konstance’s father was back on earth, he used to live in Australia, on a farm he called Scheria (a mythical island in the Odyssey); the spaceship is named the Argos (the name of Odysseus’ dog, and also suggestive of Jason’s ship, the Argo).

These characters are, necessarily, held together not only by “Cloud Cuckoo Land” the fable but by “Cloud Cuckoo Land” the novel. Having laid out his flagrantly disparate cast, Doerr must insist on that cast’s almost freakish genealogical coherence. This formal insistence becomes the novel’s raison d’être. We have no idea how these people or periods relate to one another, or how they rationally could. But storytelling, redefined as esoteric manipulation, will reveal the code; the novelist is the magus, the secret historian. Although the book is largely set in a recognizable actual world, largely obeys the laws of physics, and features human beings, storytelling, stripped of organic necessity, aerates itself into fantasy.

Novels that, like “Cloud Cuckoo Land,” follow the “ Cloud Atlas ” suite form provide an opportunity for authorial bravado. (David Mitchell has much to answer for.) Doerr’s new book and its predecessor open with narrative propositions. The reader is, in effect, presented with a vast map, pegged with tiny characters who begin very far apart. Slowly, these dots will get bigger and move toward one another. In “All the Light We Cannot See,” for instance, we open in Saint-Malo, with sixteen-year-old Marie-Laure. Two other characters—a tenderhearted German radio engineer and a Nazi gem hunter—are converging on Marie-Laure, and it will take the course of the book for them to do so.

Doerr likes to start in medias res, and then to go back to the origins of his stories and work forward again (or forward and backward and forward again, in alternation). He dangles that first picture, the confusing snapshot from the thick of things, as the prize awaiting the properly plot-hungry, plot-patient reader. So that novel begins in 1944, and promptly takes us back to Marie-Laure at the age of six, in Paris, in order to demonstrate how she and her father ended up in Saint-Malo with a diamond bigger than the Ritz. At the opening of “Cloud Cuckoo Land,” we’re presented with the incomprehensible tableau of fourteen-year-old Konstance hurtling through space in the Argos. She has recently discovered the connection between her father and Antonius Diogenes’ tale of Aethon. But the scene quickly gives way to the snatched preludes of two other stories: Zeno at the Idaho library with the children, Seymour in a parked car with his bomb. These stories, too, quickly reverse—we see Zeno at seven, in 1941, and Seymour at three, in 2005—in order to go forward once again more slowly. When we next encounter Konstance, a hundred or so pages after her first appearance, she is four years old. In this way, the reader is always playing Doerr’s game of catch-up, eager to reach a finale that has already functioned as prelude.

As a stylist, Doerr has several warring modes. One of them comes from what could be called the Richard Powers school of emergency realism. Omeir isn’t merely afraid; “tendrils of panic clutch his windpipe.” Anna isn’t merely very thirsty; “thirst twists through her.” When Seymour thinks, “questions chase one another around the carousel of his mind.” But Doerr’s habitual register is less obtrusive. He often writes very well, and is excellent at the pop-up scenic evocations required by big novels that move around a lot. Although the arcs of his stories may tend toward a kind of sentimental pedagogy, his sentences, in the main, scrupulously avoid it. He knows how to animate a picture; he knows which details to choose. Here is Zeno as a young infantryman, fighting in the Korean War. The supply truck he’s riding in has been ambushed by enemy soldiers:

A middle-aged Chinese soldier with small beige teeth drags him out of the passenger’s door and into the snow. In another breath there are twenty men around him. . . . Some carry Russian burp guns; some have rifles that look four decades old; some wear only rice bags for shoes. Most are tearing open C rations they’ve taken out of the back of the Dodge. One holds a can printed PINEAPPLE UPSIDE-DOWN CAKE while another tries to saw it open with a bayonet; another stuffs his mouth with crackers; a fourth bites into a head of cabbage as though it were a giant apple.

Link copied

Zeno is captured, and put in a P.O.W. camp. Doerr deftly provides the equivalent of a cinematic establishing shot: “In winter stalagmites of frozen urine reach up and out of the latrines. The river freezes, the Chinese heat fewer bunkhouses, and the Americans and Brits are merged.” We’re up and running.

Yet his prose is regularly on the verge of formula, and too often capitulates to baser needs. “All the Light We Cannot See” recycles a goodly amount of Nazi tropes: impeccably dressed officers brush invisible specks of dust from their uniforms, or pull off their leather gloves one finger at a time. A boy is “thin as a blade of grass, skin as pale as cream.” In both novels, when Doerr wants to gesture at immensity, he . . . gestures. The telltale formulation involves the word “thousand.” From his previous novel: “At the lowest tides, the barnacled ribs of a thousand shipwrecks stick out above the sea.” And: “A thousand frozen stars preside over the quad.” And: “A thousand eyes peer out.” And: “A shell screams over the house. He thinks: I only want to sit here with her for a thousand hours.” He’s at it again in the new book. Anna “practices her letter on the thousand blank pages of her mind.” Zeno, as a little boy, is afraid: “Only now does fear fill his body, a thousand snakes slithering beneath his skin.” Konstance, too, is on edge: “From the shadows crawl a thousand demons.”

It’s a minor tic, appealing even in its unconsciousness. But this double movement, simultaneously toward the enlargement of intensity and the routine of formula, tells us something about the strange terrain of Doerr’s novels, which leave so little for the mean, for the middle. Proficient prose supports an extravagance of storytelling; excellent craftsmanship holds together a flashing edifice; tight plotting underwrites earnestly immense themes. Every so often, a more subtle observer emerges amid these gapped extremities, a writer interested merely in honoring the world about him, a stylist capable of something as beautiful as “the quick, drastic strikes of a bow dashing across the strings of a violin,” or this taut description of an Idaho winter: “Icicles fang the eaves.”

“Cloud Cuckoo Land” has little time for such mimetic modesties and accidental beauties. Far more even than its predecessor, it is fraught with preachment. This novel of performative storytelling that is also a novel about storytelling is dedicated to “the librarians then, now, and in the years to come.” Two anxieties, reinforcing each other, are at play: the end of the book, and nothing less than the end of the world. Which is to say, the book is under threat both by the erosion of cultural memory and by the climate crisis. Doerr’s invention of the fable of Aethon is also Doerr’s fable about the precariousness of the book: a fragment that barely made it into the modern world, surviving only by the tenuous links between successive generations of readers. Books, a teacher tells Anna, are precious repositories “for the memories of people who have lived before. . . . But books, like people, die.” Elsewhere, another scribe reminds Anna that time “wipes the old books from the world,” and, likening Constantinople to an ark full of books, neatly twins this novel’s emphases: “The ark has hit the rocks, child. And the tide is washing in.”

The terminality of the message perhaps explains the frantic didacticism of all the theming. Libraries are everywhere here, from Constantinople to Idaho. In one of the book’s most tender episodes, Zeno meets an English soldier in Korea named Rex Browning, and surreptitiously falls in love with him. Rex is a classicist, who tells Zeno that he might be named for Zenodotus, “the first librarian at the library at Alexandria.” Later in the novel, back in England, Rex writes a book titled “Compendium of Lost Books.” The spaceship Argos offers an elegiac, troubling vision of life without actual libraries; its brain is a Siri-like oracle known as Sibyl, a vast digital library of everything we ever knew: “the collective wisdom of our species. Every map ever drawn, every census ever taken, every book ever published, every football match, every symphony, every edition of every newspaper, the genomic maps of over one million species—everything we can imagine and everything we might ever need.”

Gradually, you come to understand that the desperate cross-referencing and thematic reinforcing borrow not so much from the model of the Internet as from the model of the library. Just as this novel full of stories is also about storytelling, so this novel about the importance of libraries mimics a library; it is stuffed with texts and allusions and connections, an ideal compendium of “the collective wisdom of our species.”

It’s here, perhaps, that “Cloud Cuckoo Land” becomes an affecting document. As a novelist, Doerr is utterly unembarrassed by statement. For him, storytelling is entertainment and sermon; the novel is really a fable. Late Tolstoy might have approved. And since we are living in critical times, the lessons are made very legible: the book is at risk; the world is at risk; we should not seek out distant utopias but instead cultivate our burnt gardens. Above all—or, rather, underneath all—everything is connected. Seymour, vibrantly, morbidly alive to our self-destruction, realizes this:

Seymour studies the quantities of methane locked in melting Siberian permafrost. Reading about declining owl populations led him to deforestation which led to soil erosion which led to ocean pollution which led to coral bleaching, everything warming, melting, and dying faster than scientists predicted, every system on the planet connected by countless invisible threads to every other: cricket players in Delhi vomiting from Chinese air pollution, Indonesian peat fires pushing billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere over California, million-acre bushfires in Australia turning what’s left of New Zealand’s glaciers pink.

If this sounds like it could almost have been written by Don DeLillo , there’s a reason. The apprehension that everything is connected is essentially a paranoid insight (and a useful one for the novelist, who can pose as esoteric decoder). What’s poignant here is the way one kind of connectivity helplessly collapses into another. Seymour’s Internet search, today’s version of a library search, is an exercise in scholarly connection, of the kind this novel also enjoys—everyone and everything is related by cross-reference and classical allusion and thematic inheritance. But “Cloud Cuckoo Land” embodies and imposes a darker connective energy, too. Climate change, after all, enforces an entirely justifiable paranoia: we are indeed part of a shared system, in which melting in one place arrives by flood in a second place and fire in yet another. One form of connectivity might be almost utopian; the other has become powerfully dystopian. History’s enormous optimistic library becomes reality’s enormous pessimistic prison. Each vision, as in Seymour’s alarmed search, fuels another in this book.

Artistically, this sincere moral and political urgency does the novel few favors, as the book veers between its relentless thematic coherence and wild fantasias of storytelling. But that urgency may also account for the novel’s brute didactic power; it is hard to read, without a shudder, the sections about the desperate and deluded Argonauts, committed to voyaging for centuries through space-time because life on earth has failed. A pity, then, and a telling one, that Doerr finally resolves nearly every story optimistically and soothingly. And Konstance’s hurtling spaceship? Oh, it turns out to be the biggest therapeutic contraption of all. ♦

A previous version of this article misstated the name of the Museum of Natural History in Paris.

New Yorker Favorites

- How we became infected by chain e-mail .

- Twelve classic movies to watch with your kids.

- The secret lives of fungi .

- The photographer who claimed to capture the ghost of Abraham Lincoln .

- Why are Americans still uncomfortable with atheism ?

- The enduring romance of the night train .

- Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Kyle Chayka

By Anthony Lane

By Justin Taylor

By Clarissa Wei

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Cloud Atlas

Embed our reviews widget for this book

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

Book Reviews

Anthony doerr's new novel spans centuries, yet fits together like clockwork.

Jason Sheehan

In 15th century Constantinople, a young girl scales the high walls of an abandoned monastery said to be haunted by spirits who carry their chamberlain through the broken halls on a throne made of bones.

In the 1940s, in Lakeport, Idaho, a boy follows his father to a new job, a new life and, eventually, a new war.

In 2020, a troubled teenager sits in his car outside the Lakeport public library, a gun in his pocket, a bomb in the backpack beside him.

In 2146, mission year 65 of the Argos — a generation ship headed for a new home on Beta Oph2 — a girl arranges scraps of paper on the floor inside a sealed room. She has been inside for 300-some days, her only company an artificial intelligence called Sybil who contains the sum total of all mankind's knowledge.

These are the points of the loom on which Anthony Doerr weaves his newest book, Cloud Cuckoo Land — a tapestry that stretches across centuries, linking the lives of these characters through words, stories, libraries and, most notably, an invented manuscript (for which the novel is named) written by the very real ancient Greek author Antonius Diogenes.

In Constantinople, Anna is a failure as a seamstress, but learns to read ancient Greek from a dying tutor to rich children in exchange for stolen wine and bread. She spends her nights thieving, her days in a monastery with her sister. She meets a group of Italian scholars looking for ancient manuscripts, grave-robbing the city ahead of the war that is coming. Outside the walls, there is a boy, Omeir, with a cleft palate and a deep connection to his two massive oxen, Moonlight and Tree. He has been conscripted into the Sultan's army besieging the city but will, months later, find Anna among those who've fled.

Author Interviews

Anthony doerr on the spark that inspired 'cloud cuckoo land'.

A Fractured Tale Of Time, War And A Really Big Diamond

In the 1950's, Zeno Ninis, the boy in Lakeport, lost his father in WWII and goes himself to fight in the Korean War. He is captured, survives, ends up translating the Diogenes manuscript and, decades later, working in the library of his hometown, he helps a group of schoolchildren stage "Cloud Cuckoo Land" as a play. It is the night of the dress rehearsal that Seymour, the ecoterrorist, brings his bomb to the library, thinking it deserted, hoping only to damage or destroy the model home and offices of a real estate development company next door.

Doerr does amazing things with his story, with this narrative spread unevenly across such disparate characters, such different voices. He makes links that persist across centuries, flits from place to place and person to person with an enviable grace, making seemingly impossible logical and temporal leaps seem as natural as breath. Between the covers, across hundreds of pages, he has everything — birth and death, love and war, heists, escapes, the particular (though not unique) perils of growing up in 1453, 1940, 2020 and 2146. He breaks the story into a thousand pieces, then spends every page carefully putting it all back in order again.

Cloud Cuckoo Land is a book that is in love with nature and with libraries, that disdains advancement and yet embraces technology (to read his descriptions of the construction of a massive cannon outside the walls of Constantinople or the experience of virtual reality aboard a space-ark a century from now are masterpieces of worldbuilding and wonder). For his central, eponymous hook, Doerr invents what is a ridiculous, Big Rock Candy Mountain kind of ancient Greek yarn about a dim shepherd named Aethon who hears a story of an imaginary city in the sky where there is no pain or hunger or suffering and believes it real; who is turned into a donkey, a fish and an owl in his pursuit of this place — each echoing the lives of those characters whose stories intersect across the centuries, whose lives are shaped by Diogenes's comic tale.

Doerr does not overstate the importance of the story-within-a-story. If anything, he makes a point of reminding us again and again how easy it is for books to be lost across the ages — the staggering number of histories, tales, songs, account books, speeches, poems and stories that never made it through the meatgrinder of history. Diogenes' "Cloud Cuckoo Land" survived by luck, by chance, through sacrifice and dedication. There are no heroes or villains, no global plots, no secret societies bent on controlling this lost manuscript. There's just a book thief, a boy and his ox, a messed-up kid who lost his best friend, a man putting on a children's play, a girl talking to a supercomputer.

The book is a puzzle. The greatest joy in it comes from watching the pieces snap into place. It is an epic of the quietest kind, whispering across 600 years in a voice no louder than a librarian's. It is a book about books, a story about stories. It is tragedy and comedy and myth and fable and a warning and a comfort all at the same time. It says, Life is hard. Everyone believes the world is ending all the time. But so far, all of them have been wrong .

It says that if stories can survive, maybe we can, too.

Jason Sheehan knows stuff about food, video games, books and Star Blazers . He's the restaurant critic at Philadelphia magazine, but when no one is looking, he spends his time writing books about giant robots and ray guns. Tales From the Radiation Age is his latest book.

Advertisement

Supported by

editors’ choice

8 New Books We Recommend This Week

Suggested reading from critics and editors at The New York Times.

- Share full article

Our recommended books this week include three very different memoirs. In “Grief Is for People,” Sloane Crosley pays tribute to a lost friend and mentor; in “Replay,” the video-game designer Jordan Mechner presents a graphic family memoir of three generations; and in “What Have We Here?” the actor Billy Dee Williams looks back at his life in Hollywood and beyond.

Also up this week: a history of the shipping companies that helped Jewish refugees flee Europe before World War I and a humane portrait of people who ended up more or less alone at death, their bodies unclaimed in a Los Angeles morgue. In fiction we recommend a posthumous story collection by a writer who died on the cusp of success, along with a ripped-from-the-headlines thriller and a big supernatural novel from a writer previously celebrated for her short fiction. Happy reading. — Gregory Cowles

WHAT HAPPENED TO NINA? Dervla McTiernan

Despite its title, this disturbing, enthralling thriller is less concerned with what happened to 20-year-old Nina, who vanished while spending the weekend with her controlling boyfriend, than it is with how the couple’s parents — all broken, terrified and desperate in their own ways — respond to the exigencies of the moment.

“Almost painfully gripping. … The last scene will make your blood run cold.”

From Sarah Lyall’s thrillers column

Morrow | $27

THE UNCLAIMED: Abandonment and Hope in the City of Angels Pamela Prickett and Stefan Timmermans

The sociologists Pamela Prickett and Stefan Timmermans spent some 10 years studying the phenomenon of the unclaimed dead in America — and, specifically, Los Angeles. What sounds like a grim undertaking has resulted in this moving project, in which they focus on not just the deaths but the lives of four people. The end result is sobering, certainly, but important, readable and deeply humane.

“A work of grace. … Both cleareyed and disturbing, yet pulsing with empathy.”

From Dan Barry’s review

Crown | $30

THE BOOK OF LOVE Kelly Link

Three teenagers are brought back from the dead in Link’s first novel, which is set in a coastal New England town full of secrets and supernatural entities. The magic-wielding band teacher who revived them gives the kids a series of tasks to stay alive, but powerful forces conspire to thwart them.

“It’s profoundly beautiful, provokes intense emotion, offers up what feel like rooted, incontrovertible truths.”

From Amal El-Mohtar’s review

Random House | $31

GRIEF IS FOR PEOPLE Sloane Crosley

Crosley is known for her humor, but her new memoir tackles grief. The book follows the author as she works to process the loss of her friend, mentor and former boss, Russell Perreault, who died by suicide.

“The book is less than 200 pages, but the weight of suicide as a subject, paired with Crosley’s exceptional ability to write juicy conversation, prevents it from being the kind of slim volume one flies through and forgets.”

From Ashley C. Ford’s review

MCDxFSG | $27

NEIGHBORS AND OTHER STORIES Diane Oliver

This deceptively powerful posthumous collection by a writer who died at 22 follows the everyday routines of Black families as they negotiate separate but equal Jim Crow strictures, only to discover uglier truths.

“Like finding hunks of gold bullion buried in your backyard. … Belatedly bids a full-throated hello.”

From Alexandra Jacobs’s review

Grove | $27

WHAT HAVE WE HERE? Portraits of a Life Billy Dee Williams

In this effortlessly charming memoir, the 86-year-old actor traces his path from a Harlem childhood to the “Star Wars” universe, while lamenting the roles that never came his way.

“He writes with clarity and intimacy, revealing the person behind the persona. And he doesn’t scrimp on the dirty details.”

From Maya S. Cade’s review

Knopf | $32

THE LAST SHIPS FROM HAMBURG: Business, Rivalry, and the Race to Save Russia’s Jews on the Eve of World War I Steven Ujifusa

Ujifusa’s history describes the early-20th-century shipping interests that made a profit helping millions of impoverished Jews flee violence in Eastern Europe for safe harbor in America before the U.S. Congress passed laws restricting immigration.

“Thoroughly researched and beautifully written. … Truth as old as the Republic itself.”

From David Nasaw’s review

Dutton | $35

REPLAY: Memoir of an Uprooted Family Jordan Mechner

The famed video-game designer (“Prince of Persia”) pivots to personal history in this ambitious but intimate graphic novel. In it, he elegantly interweaves themes of memory and exile with family lore from three generations: a grandfather who fought in World War I; a father who fled Nazi persecution; and his own path as a globe-trotting, game-creating polymath.

“The binding theme is statelessness — imposed by chance, antisemitism and personal ambition — but memoirs are about memory, and so it is also a book about the subtleties and biases of recollection.”

From Sam Thielman’s graphics column

First Second | $29.99

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

History Is a Nightmare. Share full article. By Tom Bissell. Aug. 29, 2004. CLOUD ATLAS. By David Mitchell. 509 pp. Random House. Paper, $14.95. IT is not unheard of for a novelist of exceptional ...

A new edition of Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell, introduced by Gabrielle Zevin, is published by Sceptre on 11 April. Every author wants to write a book like David Mitchell's Cloud Atlas. Two ...

Fri 11 Jun 2010 09.22 EDT. There are two schools of thought about Cloud Atlas: the first believes it approaches genius; the second thinks it's too clever by half. When the book reached the US, it ...

*Cloud Atlas*, the unlikely new adaptation by Lana and Andy Wachowski and Tom Tykwer of David Mitchell's ingenious novel, should do well on DVD, a format whose capacity for endless replay will enable viewers to study at leisure the myriad concurrences binding the movie's half dozen plots. Better yet, the directors should hire their friend the philosopher Ken Wilber to provide expert ...

Irish writer Rooney has made a trans-Atlantic splash since publishing her first novel, Conversations With Friends, in 2017. Her second has already won the Costa Novel Award, among other honors, since it was published in Ireland and Britain last year. In outline it's a simple story, but Rooney tells it with bravura intelligence, wit, and delicacy.

In mid-fifteenth-century Constantinople, Anna, a Greek Christian, awaits the assault that has long been threatened by Muslim forces. A few hundred miles away, Omeir, a gentle country boy, finds ...

About Cloud Atlas. By the New York Times bestselling author of The Bone Clocks | Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize A postmodern visionary and one of the leading voices in twenty-first-century fiction, David Mitchell combines flat-out adventure, a Nabokovian love of puzzles, a keen eye for character, and a taste for mind-bending, philosophical and scientific speculation in the tradition of ...

Cloud Atlas is comprised of six distinct stories, told in eleven parts. But while most novels conventionally use chapters to delineate sections of their plot, Cloud Atlas dovetails its own stories together, meaning one may simply end, abruptly and without conclusion, for another to begin. The following tale takes the reader to a new time and location, essentially to begin all over again ...

It is a challenge that bests both actors, according to David Edelstein. Jay Maidment/Warner Bros. Cloud Atlas. Directors: Tom Tykwer, Andy Wachowski, Lana Wachowski. Genre: Drama. Running Time ...

Now in his new novel, David Mitchell explores with daring artistry fundamental questions of reality and identity. Cloud Atlas begins in 1850 with Adam Ewing, an American notary voyaging from the Chatham Isles to his home in California. Along the way, Ewing is befriended by a physician, Dr. Goose, who begins to treat him for a rare species of ...

By the New York Times bestselling author of The Bone Clocks | Shortlisted for the Man Booker PrizeA postmodern visionary and one of the leading voices in twenty-first-century fiction, David Mitchell combines flat-out adventure, a Nabokovian love of puzzles, a keen eye for character, and a taste for mind-bending, philosophical and scientific speculation in the tradition of Umberto Eco, Haruki ...

Cloud Atlas, published in 2004, is the third novel by British author David Mitchell.The book combines metafiction, historical fiction, contemporary fiction and science fiction, with interconnected nested stories that take the reader from the remote South Pacific in the 19th century to the island of Hawai'i in a distant post-apocalyptic future. Its title references a piece of music by Toshi ...

By Pico Iyer. Aug. 28, 2014. "I don't summon anything up," protests Holly Sykes, the down-to-earth protagonist of "The Bone Clocks," David Mitchell's latest head-spinning flight into ...

By the New York Times bestselling author of The Bone Clocks | Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize A postmodern visionary and one of the leading voices in twenty-first-century fiction, David Mitchell combines flat-out adventure, a Nabokovian love of puzzles, a keen eye for character, and a taste for mind-bending, philosophical and scientific speculation in the tradition of Umberto Eco, Haruki ...

Cloud Atlas is a remarkable achievement, a frightening, beautiful, funny, wildly inventive, elaborately conceived tour de force. It places us not in one intensely imagined world but six: six different time periods, milieus, vocabularies and literary styles …. To read Cloud Atlas is to feel perpetually off balance, often disoriented ...

The New York Times. Cloud Atlas imposes a dizzying series of milieus, characters and conflicts upon us...Each story is written quite differently - so much so that Cloud Atlas feels like a doggedly expert gloss on various writers and modes …. The novel is frustrating not because it is too smart but because it is not nearly as smart as its ...

By the New York Times bestselling author of The Bone Clocks | Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize A postmodern visionary and one of the leading voices in twenty-first-century fiction, David Mitchell combines flat-out adventure, a Nabokovian love of puzzles, a keen eye for character, and a taste for mind-bending, philosophical and scientific speculation in the tradition of Umberto Eco, Haruki ...

By the New York Times bestselling author of The Bone Clocks - Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize A postmodern visionary and one of the leading voices in twenty-first-century fiction, David Mitchell combines flat-out adventure, a Nabokovian love of puzzles, a keen eye for character, and a taste for mind-bending, philosophical and scientific speculation in the tradition of Umberto Eco, Haruki ...

At its best, reading "Genealogy of a Murder" was, for me, like reading "Cloud Atlas," David Mitchell's novel that collapses hundreds of years of history and connects generations of ...

The book is a puzzle. The greatest joy in it comes from watching the pieces snap into place. It is an epic of the quietest kind, whispering across 600 years in a voice no louder than a librarian's ...

Billy Dee Williams. In this effortlessly charming memoir, the 86-year-old actor traces his path from a Harlem childhood to the "Star Wars" universe, while lamenting the roles that never came ...