Cohort Studies: Design, Analysis, and Reporting

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH.

- PMID: 32658655

- DOI: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.014

Cohort studies are types of observational studies in which a cohort, or a group of individuals sharing some characteristic, are followed up over time, and outcomes are measured at one or more time points. Cohort studies can be classified as prospective or retrospective studies, and they have several advantages and disadvantages. This article reviews the essential characteristics of cohort studies and includes recommendations on the design, statistical analysis, and reporting of cohort studies in respiratory and critical care medicine. Tools are provided for researchers and reviewers.

Keywords: bias; cohort studies; confounding; prospective; retrospective.

Copyright © 2020 American College of Chest Physicians. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Cohort Studies*

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Guidelines as Topic

- Research Design / statistics & numerical data*

Cohort Study: Definition, Designs & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A cohort study is a type of longitudinal study where a group of individuals (cohort), often sharing a common characteristic or experience, is followed over an extended period of time to study and track outcomes, typically related to specific exposures or interventions.

In cohort studies, the participants must share a common factor or characteristic such as age, demographic, or occupation. A “cohort” is a group of subjects who share a defining characteristic.

Cohort studies are observational, so researchers will follow the subjects without manipulating any variables or interfering with their environment.

This type of study is beneficial for medical researchers, specifically in epidemiology, as scientists can use data from cohort studies to understand potential risk factors or causes of a disease.

Before any appearance of the disease is investigated, medical professionals will identify a cohort, observe the target participants over time, and collect data at regular intervals.

Weeks, months, or years later, depending on the duration of the study design, the researchers will examine any factors that differed between the individuals who developed the condition and those who did not.

They can then determine if an association exists between an exposure and an outcome and even identify disease progression and relative risk.

Retrospective

- A retrospective cohort study is a type of observational research that uses existing past data to identify two groups of individuals—those with the risk factor or exposure (cohort) and without—and follows their outcomes backward in time to determine the relationship.

- In a retrospective study , the subjects have already experienced the outcome of interest or developed the disease before starting the study.

- The researchers then look back in time to identify a cohort of subjects before developing the disease and use existing data, such as medical records, to discover any patterns.

Prospective

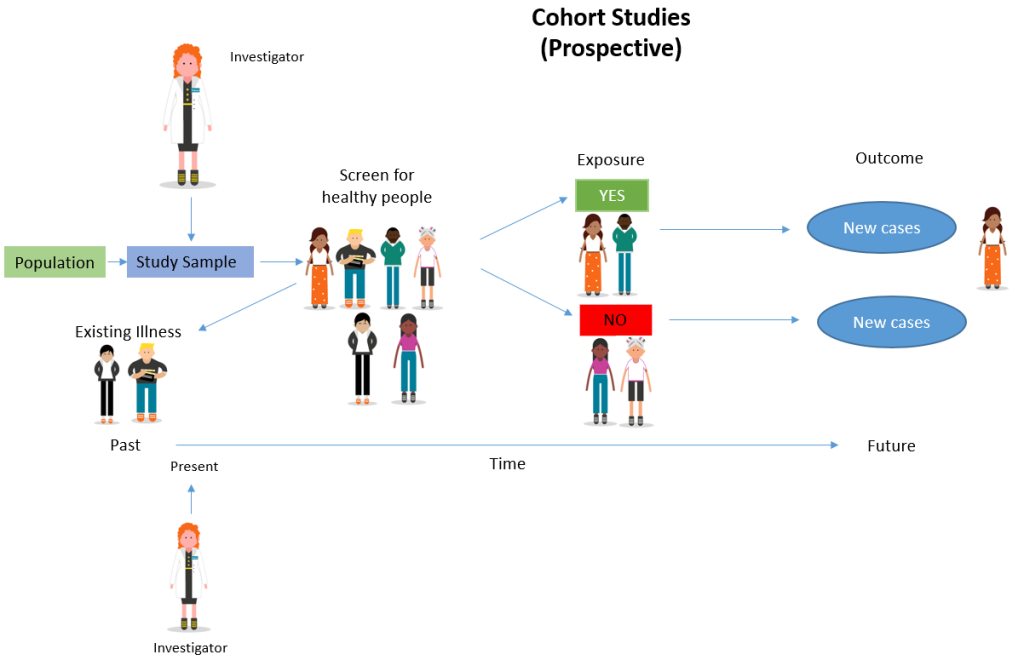

A prospective cohort study is a type of longitudinal research where a group of individuals sharing a common characteristic (cohort) is followed over time to observe and measure outcomes, often to investigate the effect of suspected risk factors.

In a prospective study , the investigators will design the study, recruit subjects, and collect baseline data on all subjects before they have developed the outcomes of interest.

- The subjects are followed and observed over a period of time to gather information and record the development of outcomes.

Determine cause-and-effect relationships

Because researchers study groups of people before they develop an illness, they can discover potential cause-and-effect relationships between certain behaviors and the development of a disease.

Provide extensive data

Cohort studies enable researchers to study the causes of disease and identify multiple risk factors associated with a single exposure. These studies can also reveal links between diseases and risk factors.

Enable studies of rare exposures

Cohort studies can be very useful for evaluating the effects and risks of rare diseases or unusual exposures, such as toxic chemicals or adverse effects of drugs.

Can measure a continuously changing relationship between exposure and outcome

Because cohort studies are longitudinal, researchers can study changes in levels of exposure over time and any changes in outcome, providing a deeper understanding of the dynamic relationship between exposure and outcome.

Limitations

Time consuming and expensive.

Cohort studies usually require multiple months or years before researchers are able to identify the causes of a disease or discover significant results. Because of this, they are often more expensive than other types of studies. Retrospective studies, though, tend to be cheaper and quicker than prospective studies as the data already exists.

Require large sample sizes

Cohort studies require large sample sizes in order for any relationships or patterns to be meaningful. Researchers are unable to generate results if there is not enough data.

Prone to bias

Because of the longitudinal nature of these studies, it is common for participants to drop out and not complete the study. The loss of follow-up in cohort studies means researchers are more likely to estimate the effects of an exposure on an outcome incorrectly.

Unable to discover why or how a certain factor is associated with a disease

Cohort studies are used to study cause-and-effect relationships between a disease and an outcome. However, they do not explain why the factors that affect these relationships exist. Experimental studies are required to determine why a certain factor is associated with a particular outcome.

The Framingham Heart Study

Studied the effects of diet, exercise, and medications on the development of hypertensive or arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, in a longitudinal population-based cohort.

The Whitehall Study

The initial prospective cohort study examined the association between employment grades and mortality rates of 17139 male civil servants over a period of ten years, beginning in 1967. When the Whitehall Study was conducted, there was no requirement to obtain ethical approval for scientific studies of this kind.

The Nurses’ Health Study

Researched long-term effects of nurses” nutrition, hormones, environment, and work-life on health and disease development.

The British Doctors Study

This was a prospective cohort study that ran from 1951 to 2001, investigating the association between smoking and the incidence of lung cancer.

The Black Women’s Health Study

Gathered information about the causes of health problems that affect Black women.

Millennium Cohort Study

Found evidence to show how various circumstances in the first stages of life can influence later health and development. The study began with an original sample of 18,818 cohort members.

The Danish Cohort Study of Psoriasis and Depression

Studied the association between psoriasis and the onset of depression.

The 1970 British Cohort Study

Followed the lives of around 17,000 people born in England, Scotland, and Wales in a single week of 1970.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. are case-control studies and cohort studies the same.

While both studies are commonly used among medical professionals to study disease, they differ.

Case-control studies are performed on individuals who already have a disease (cases) and compare them with individuals who share similar characteristics but do not have the disease (controls).

In cohort studies, on the other hand, researchers identify a group before any of the subjects have developed the disease. Then after an extended period, they examine any factors that differed between the individuals who developed the condition and those who did not.

2. What is the difference between a cross-sectional study and a cohort study?

Like case-control and cohort studies, cross-sectional studies are also used in epidemiology to identify exposures and outcomes and compare the rates of diseases and symptoms of an exposed group with an unexposed group.

However, cross-sectional studies analyze information about a population at a specific point in time, while cohort studies are carried out over longer periods.

3. What is the difference between cohort and longitudinal studies?

A cohort study is a specific type of longitudinal study. Another type of longitudinal study is called a panel study which involves sampling a cross-section of individuals at specific intervals for an extended period.

Panel studies are a type of prospective study, while cohort studies can be either prospective or retrospective.

Barrett D, Noble H. What are cohort studies? Evidence-Based Nursing 2019; 22:95-96.

Kandola, A.A., Osborn, D.P.J., Stubbs, B. et al. Individual and combined associations between cardiorespiratory fitness and grip strength with common mental disorders: a prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. BMC Med 18, 303 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01782-9

Marmot, M. G., Rose, G., Shipley, M., & Hamilton, P. J. (1978). Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 32(4), 244-249.

Rosenberg, L., Adams-Campbell, L., & Palmer, J. R. (1995). The Black Women’s Health Study: a follow-up study for causes and preventions of illness. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association (1972), 50(2), 56-58.

Samer Hammoudeh, Wessam Gadelhaq and Ibrahim Janahi (November 5th 2018). Prospective Cohort Studies in Medical Research, Cohort Studies in Health Sciences, R. Mauricio Barría, IntechOpen, DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.76514. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/60939

Setia M. S. (2016). Methodology Series Module 1: Cohort Studies. Indian journal of dermatology, 61(1), 21–25. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5154.174011

Zabor, E. C., Kaizer, A. M., & Hobbs, B. P. (2020). Randomized Controlled Trials. Chest, 158(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.013

Further Information

- Cohort Effect? Definition and Examples

- Barrett, D., & Noble, H. (2019). What are cohort studies?. Evidence-based nursing, 22(4), 95-96.

- The Whitehall Studies

- Euser, A. M., Zoccali, C., Jager, K. J., & Dekker, F. W. (2009). Cohort studies: prospective versus retrospective. Nephron Clinical Practice, 113(3), c214-c217.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Study designs: Part 1 – An overview and classification

Priya ranganathan, rakesh aggarwal.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr. Priya Ranganathan, Department of Anaesthesiology, Tata Memorial Centre, Ernest Borges Road, Parel, Mumbai - 400 012, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: [email protected]

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

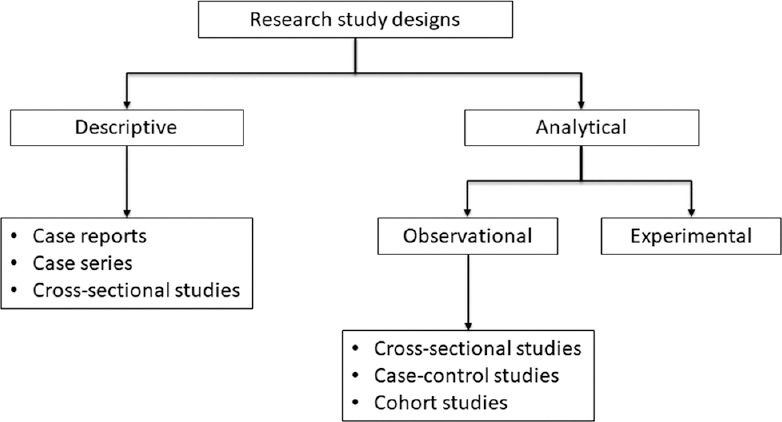

There are several types of research study designs, each with its inherent strengths and flaws. The study design used to answer a particular research question depends on the nature of the question and the availability of resources. In this article, which is the first part of a series on “study designs,” we provide an overview of research study designs and their classification. The subsequent articles will focus on individual designs.

Keywords: Epidemiologic methods, research design, research methodology

INTRODUCTION

Research study design is a framework, or the set of methods and procedures used to collect and analyze data on variables specified in a particular research problem.

Research study designs are of many types, each with its advantages and limitations. The type of study design used to answer a particular research question is determined by the nature of question, the goal of research, and the availability of resources. Since the design of a study can affect the validity of its results, it is important to understand the different types of study designs and their strengths and limitations.

There are some terms that are used frequently while classifying study designs which are described in the following sections.

A variable represents a measurable attribute that varies across study units, for example, individual participants in a study, or at times even when measured in an individual person over time. Some examples of variables include age, sex, weight, height, health status, alive/dead, diseased/healthy, annual income, smoking yes/no, and treated/untreated.

Exposure (or intervention) and outcome variables

A large proportion of research studies assess the relationship between two variables. Here, the question is whether one variable is associated with or responsible for change in the value of the other variable. Exposure (or intervention) refers to the risk factor whose effect is being studied. It is also referred to as the independent or the predictor variable. The outcome (or predicted or dependent) variable develops as a consequence of the exposure (or intervention). Typically, the term “exposure” is used when the “causative” variable is naturally determined (as in observational studies – examples include age, sex, smoking, and educational status), and the term “intervention” is preferred where the researcher assigns some or all participants to receive a particular treatment for the purpose of the study (experimental studies – e.g., administration of a drug). If a drug had been started in some individuals but not in the others, before the study started, this counts as exposure, and not as intervention – since the drug was not started specifically for the study.

Observational versus interventional (or experimental) studies

Observational studies are those where the researcher is documenting a naturally occurring relationship between the exposure and the outcome that he/she is studying. The researcher does not do any active intervention in any individual, and the exposure has already been decided naturally or by some other factor. For example, looking at the incidence of lung cancer in smokers versus nonsmokers, or comparing the antenatal dietary habits of mothers with normal and low-birth babies. In these studies, the investigator did not play any role in determining the smoking or dietary habit in individuals.

For an exposure to determine the outcome, it must precede the latter. Any variable that occurs simultaneously with or following the outcome cannot be causative, and hence is not considered as an “exposure.”

Observational studies can be either descriptive (nonanalytical) or analytical (inferential) – this is discussed later in this article.

Interventional studies are experiments where the researcher actively performs an intervention in some or all members of a group of participants. This intervention could take many forms – for example, administration of a drug or vaccine, performance of a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure, and introduction of an educational tool. For example, a study could randomly assign persons to receive aspirin or placebo for a specific duration and assess the effect on the risk of developing cerebrovascular events.

Descriptive versus analytical studies

Descriptive (or nonanalytical) studies, as the name suggests, merely try to describe the data on one or more characteristics of a group of individuals. These do not try to answer questions or establish relationships between variables. Examples of descriptive studies include case reports, case series, and cross-sectional surveys (please note that cross-sectional surveys may be analytical studies as well – this will be discussed in the next article in this series). Examples of descriptive studies include a survey of dietary habits among pregnant women or a case series of patients with an unusual reaction to a drug.

Analytical studies attempt to test a hypothesis and establish causal relationships between variables. In these studies, the researcher assesses the effect of an exposure (or intervention) on an outcome. As described earlier, analytical studies can be observational (if the exposure is naturally determined) or interventional (if the researcher actively administers the intervention).

Directionality of study designs

Based on the direction of inquiry, study designs may be classified as forward-direction or backward-direction. In forward-direction studies, the researcher starts with determining the exposure to a risk factor and then assesses whether the outcome occurs at a future time point. This design is known as a cohort study. For example, a researcher can follow a group of smokers and a group of nonsmokers to determine the incidence of lung cancer in each. In backward-direction studies, the researcher begins by determining whether the outcome is present (cases vs. noncases [also called controls]) and then traces the presence of prior exposure to a risk factor. These are known as case–control studies. For example, a researcher identifies a group of normal-weight babies and a group of low-birth weight babies and then asks the mothers about their dietary habits during the index pregnancy.

Prospective versus retrospective study designs

The terms “prospective” and “retrospective” refer to the timing of the research in relation to the development of the outcome. In retrospective studies, the outcome of interest has already occurred (or not occurred – e.g., in controls) in each individual by the time s/he is enrolled, and the data are collected either from records or by asking participants to recall exposures. There is no follow-up of participants. By contrast, in prospective studies, the outcome (and sometimes even the exposure or intervention) has not occurred when the study starts and participants are followed up over a period of time to determine the occurrence of outcomes. Typically, most cohort studies are prospective studies (though there may be retrospective cohorts), whereas case–control studies are retrospective studies. An interventional study has to be, by definition, a prospective study since the investigator determines the exposure for each study participant and then follows them to observe outcomes.

The terms “prospective” versus “retrospective” studies can be confusing. Let us think of an investigator who starts a case–control study. To him/her, the process of enrolling cases and controls over a period of several months appears prospective. Hence, the use of these terms is best avoided. Or, at the very least, one must be clear that the terms relate to work flow for each individual study participant, and not to the study as a whole.

Classification of study designs

Figure 1 depicts a simple classification of research study designs. The Centre for Evidence-based Medicine has put forward a useful three-point algorithm which can help determine the design of a research study from its methods section:[ 1 ]

Classification of research study designs

Does the study describe the characteristics of a sample or does it attempt to analyze (or draw inferences about) the relationship between two variables? – If no, then it is a descriptive study, and if yes, it is an analytical (inferential) study

If analytical, did the investigator determine the exposure? – If no, it is an observational study, and if yes, it is an experimental study

If observational, when was the outcome determined? – at the start of the study (case–control study), at the end of a period of follow-up (cohort study), or simultaneously (cross sectional).

In the next few pieces in the series, we will discuss various study designs in greater detail.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- 1. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Study Designs. 2016. [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 04]. Available from: https://www.cebm.net/2014/04/study-designs/

- View on publisher site

- PDF (482.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Study Design 101: Cohort Study

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

A study design where one or more samples (called cohorts) are followed prospectively and subsequent status evaluations with respect to a disease or outcome are conducted to determine which initial participants exposure characteristics (risk factors) are associated with it. As the study is conducted, outcome from participants in each cohort is measured and relationships with specific characteristics determined

- Subjects in cohorts can be matched, which limits the influence of confounding variables

- Standardization of criteria/outcome is possible

- Easier and cheaper than a randomized controlled trial (RCT)

Disadvantages

- Cohorts can be difficult to identify due to confounding variables

- No randomization, which means that imbalances in patient characteristics could exist

- Blinding/masking is difficult

- Outcome of interest could take time to occur

Design pitfalls to look out for

The cohorts need to be chosen from separate, but similar, populations.

How many differences are there between the control cohort and the experiment cohort? Will those differences cloud the study outcomes?

Fictitious Example

A cohort study was designed to assess the impact of sun exposure on skin damage in beach volleyball players. During a weekend tournament, players from one team wore waterproof, SPF 35 sunscreen, while players from the other team did not wear any sunscreen. At the end of the volleyball tournament players' skin from both teams was analyzed for texture, sun damage, and burns. Comparisons of skin damage were then made based on the use of sunscreen. The analysis showed a significant difference between the cohorts in terms of the skin damage.

Real-life Examples

Hoepner, L., Whyatt, R., Widen, E., Hassoun, A., Oberfield, S., Mueller, N., ... Rundle, A. (2016). Bisphenol A and Adiposity in an Inner-City Birth Cohort. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124 (10), 1644-1650. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP205

This longitudinal cohort study looked at whether exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) early in life affects obesity levels in children later in life. Positive associations were found between prenatal BPA concentrations in urine and increased fat mass index, percent body fat, and waist circumference at age seven.

Lao, X., Liu, X., Deng, H., Chan, T., Ho, K., Wang, F., ... Yeoh, E. (2018). Sleep Quality, Sleep Duration, and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study With 60,586 Adults. Journal Of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14 (1), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6894

This prospective cohort study explored "the joint effects of sleep quality and sleep duration on the development of coronary heart disease." The study included 60,586 participants and an association was shown between increased risk of coronary heart disease and individuals who experienced short sleep duration and poor sleep quality. Long sleep duration did not demonstrate a significant association.

Related Formulas

- Relative Risk

Related Terms

A group that shares the same characteristics among its members (population).

Confounding Variables

Variables that cause/prevent an outcome from occurring outside of or along with the variable being studied. These variables render it difficult or impossible to distinguish the relationship between the variable and outcome being studied).

Population Bias/Volunteer Bias

A sample may be skewed by those who are selected or self-selected into a study. If only certain portions of a population are considered in the selection process, the results of a study may have poor validity.

Prospective Study

A study that moves forward in time, or that the outcomes are being observed as they occur, as opposed to a retrospective study, which looks back on outcomes that have already taken place.

Now test yourself!

1. In a cohort study, an exposure is assessed and then participants are followed prospectively to observe whether they develop the outcome.

a) True b) False

2. Cohort Studies generally look at which of the following?

a) Determining the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic methods b) Identifying patient characteristics or risk factors associated with a disease or outcome c) Variations among the clinical manifestations of patients with a disease d) The impact of blinding or masking a study population

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- Case Reports

- << Previous: Case Control Study

- Next: Randomized Controlled Trial >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2962

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Cohort studies: prospective and retrospective designs

Posted on 6th March 2019 by Izabel de Oliveira

In epidemiology, the term “cohort” is used to define a set of people followed for a certain period of time. W. H. Frost, a 20th century epidemiologist, was the first to adopt the term in a 1935 publication, when he assessed age-specific and tuberculosis-specific mortality rates. The epidemiological definition of the word currently means:

a group of people with certain characteristics, followed up in order to determine incidence or mortality by any specific disease, all causes of death or some other outcome. [1]

Cohort study design is described as ‘observational’ because, unlike clinical studies, there is no intervention. [2] Because exposure is identified before outcome , cohort studies are considered to provide stronger scientific evidence than other observational studies such as case-control studies. [1] A fundamental characteristic of the study is that at the starting point, subjects are identified and exposure to particular risk factors is assessed. Subsequently, the frequency of the outcome, usually the incidence of disease or death over a period of time, is measured and related to exposure status. [3]

Relative risk (RR) is the measure of association that is applied for the analysis of the results in cohort studies. It compares the incidence of the disease in the exposed group with the incidence in the non-exposed group, hence the name relative risk or risk ratio. If the incidence in the two groups is equal, the value for the RR will be 1, but if the value is greater than 1, this indicates a positive relationship between the risk factor and the outcome. In order to determine if the sample studied reflects a real effect of the risk factor in the population, the sample variability of the findings may be evaluated through tests of significance or confidence intervals. [4]

Advantages of cohort studies include the possibility of examining multiple results from a given exposure, determining disease rates in exposed and unexposed individuals over time, and investigating multiple exposures. In addition, cohort studies are less susceptible to selection bias than case-control studies. The disadvantages are the weaknesses of observational design, the inefficiency to study rare diseases or those with long periods of latency, high costs, time consuming, and the loss of participants throughout the follow-up which may compromise the validity of the results. [5]

Prospective Cohort Studies

Prospective cohort studies are characterised by the selection of the cohort and the measurement of risk factors or exposures before the outcome occurs, thus establishing temporality, an important factor in determining causality. This design provides a different advantage over case-control studies in which exposure and disease are assessed at the same time. [6]

The study is carried out in three fundamental stages: identification of the individuals, observation of each group over time to evaluate the development of the disease in the groups, and comparison of the risk of onset of the disease between exposed and non-exposed groups. [5]

The main disadvantage to prospective cohort studies is the cost. It requires a large number of individuals to be followed up for long periods of time [6] and this can be difficult due to loss to follow-up or withdrawal by the individuals studied. [1] Biases may occur, especially if there is significant loss during follow-up. [6]

It is important to minimise loss to follow-up , a situation in which the researcher loses contact with the individual, resulting in missing data. When loss to follow-up of many individuals occurs, the internal validity of the study is reduced. As a general rule, the loss rate should not exceed 20% of the sample. Any systematic differences related to the outcome or exposure of risk factors for those who drop out and those who remain in the study should be examined, if possible. Strategies to avoid loss to follow-up are to exclude individuals who are likely to be lost, such as those who plan to move, and to obtain information to enable future tracking and to maintain periodic contact. [1]

Prospective design is inefficient and inappropriate for the study of rare diseases, but it becomes more efficient when there is an increase in the frequency of the disease in the population. [6]

The Nurses’ Health Study…

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) [7] is among the largest prospective investigation into the risk factors for major chronic diseases in women. Donna Shalala, former Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, called the NHS “one of the most significant studies ever conducted on the health of women.”

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) was established by Dr. Frank Speizer in 1976 with continued funding from the National Institutes of Health since then. The primary motivation for the study was to investigate the potential long-term consequences of oral contraceptives which were being prescribed to millions of women.

Nurses were selected as the study population because of their knowledge about health and their ability to provide complete and accurate information regarding various diseases due to their nursing education. They were relatively easy to follow over time and were motivated to participate in a long-term study. The cohort was limited to married women due to the sensitivity of questions about contraceptive use at that time.

The original focus of the study was on contraceptive methods, smoking, cancer, and heart disease, but has expanded over time to include research on many other lifestyle factors, behaviours, personal characteristics, and also other diseases.

Retrospective Cohort Studies

Cohort studies can also be retrospective. Retrospective cohorts are also called historical cohorts. [1,8] A retrospective cohort study considers events that have already occurred. Health records of a certain group of patients would already have been collected and stored in a database, so it is possible to identify a group of patients – the cohort – and reconstruct their experience as if it had been prospectively followed up. [2]

Although patient information was probably collected prospectively, the cohort would not have initially identified the goal of following individuals and investigating the association between risk factor and outcome. In a retrospective study, it is likely that not all relevant risk factors have been recorded. This may affect the validity of a reported association between risk factor and outcome when adjusted for confounding . In addition, it is possible that the measurement of risk factors and outcomes would not have been as accurate as in a prospective cohort study. [2]

Many of the advantages and disadvantages of retrospective cohort studies are similar to those of prospective studies. As previously described, retrospective cohort studies are typically constructed from previously collected records, in contrast to prospective design, which involves identification of a prospectively followed group, with the objective of investigating the association between one or more risk factors and outcome. However, an advantage to both study designs is that exposure to risk factors can be recorded before the outcome occurs. This is important because it allows the sequence of risk and outcome factors to be evaluated. [8]

Use of previously collected and stored records in a database indicates that the retrospective cohort study is relatively inexpensive and quick and easy to perform. However, with retrospective cohorts, it is possible that not all relevant risk factors have been identified and recorded. Another disadvantage is that many health professionals will have become involved in patient care, making the measurement of risk factors and outcomes less consistent than that achieved with a prospective study design. [8]

Dying to be famous…

Rock and pop fame is associated with risk taking, substance use and premature mortality. This retrospective cohort study [9] examined the relationships between fame and premature mortality and tested how these relationships vary with the type of performer (solo or band member) and nationality and whether the cause of death was linked to adverse childhood experiences.

The cohort included 1,489 rock and pop stars that reached fame between 1956 and 2006. The study examined the risk and protective factors for star mortality, relative contributions of adverse childhood experiences and other performance characteristics to cause premature death between rock and pop stars.

Although artists are generally not accessible through search techniques, considerable information is available through biographical publications, news and other media coverage. The accuracy and completeness of the data collected from the media and biographical sources cannot be quantified. However, such limitations are unlikely to have generated the patterns identified in this study.

The study concluded that the association between fame and mortality is mainly conditioned to performers’ characteristics. Adverse experiences in their lives predisposed them to adopt health-damaging behaviours, and fame and wealth provide greater opportunities to engage in risk-taking. Young people wish to emulate their idols, so it is important they recognise that drug abuse and risk-taking may be rooted in negative experiences rather than seeing them related to success.

Take home points:

- Cohort studies are appropriate studies to evaluate associations between multiple exposures and multiple outcomes.

- An advantage of prospective and retrospective cohort designs is that they are able to examine the temporal relationship between the exposure and the outcome.

Izabel de Oliveira

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Cohort studies: prospective and retrospective designs

Please connect @[email protected]

nice page, i reccomend to heve ppt of the updates on the site with references.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Cluster Randomized Trials: Concepts

This blog summarizes the concepts of cluster randomization, and the logistical and statistical considerations while designing a cluster randomized controlled trial.

Expertise-based Randomized Controlled Trials

This blog summarizes the concepts of Expertise-based randomized controlled trials with a focus on the advantages and challenges associated with this type of study.

An introduction to different types of study design

Conducting successful research requires choosing the appropriate study design. This article describes the most common types of designs conducted by researchers.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Abstract. Cohort studies are types of observational studies in which a cohort, or a group of individuals sharing some characteristic, are followed up over time, and outcomes are measured at one or more time points. Cohort studies can be classified as prospective or retrospective studies, and they have several advantages and disadvantages.

Cohort studies are a type of observational study that can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. They can be used to conduct both exploratory research and explanatory research depending on the research topic. In prospective cohort studies, data is collected over time to compare the occurrence of the outcome of interest in those who were ...

A prospective cohort study is a type of longitudinal research where a group of individuals sharing a common characteristic (cohort) is followed over time to observe and measure outcomes, often to investigate the effect of suspected risk factors. In a prospective study, the investigators will design the study, recruit subjects, and collect ...

In clinical research, cohort studies are appropriate when there is evidence to suggest an association between an exposure and an outcome, and the time interval between exposure and the development of outcome is reasonable. Cohort studies are the design of choice for determining the incidence and natural history of a condition.

Research study design is a framework, or the set of methods and procedures used to collect and analyze data on variables specified in a particular research problem. ... Typically, most cohort studies are prospective studies (though there may be retrospective cohorts), whereas case-control studies are retrospective studies. An interventional ...

Design, Analysis, and Reporting. Cohort studies are types of observational studies in which a cohort, or a group of individuals sharing some characteristic, are followed up over time, and outcomes are measured at one or more time points. Cohort studies can be classified as prospective or retrospective studies, and they have several advantages ...

Similarly, cohort studies provide complete data on a subject's exposure (multiple outcomes for single exposure can also be assessed) and are the best study design to assess the incidence of a ...

Abstract. In a cohort study, a group of subjects (the cohort) is followed for a period of time; assessments are conducted at baseline, during follow-up, and at the end of follow-up. Cohort studies are, therefore, empirical, longitudinal studies based on data obtained from a sample; they are also observational and (usually) naturalistic.

A study design where one or more samples (called cohorts) are followed prospectively and subsequent status evaluations with respect to a disease or outcome are conducted to determine which initial participants exposure characteristics (risk factors) are associated with it. As the study is conducted, outcome from participants in each cohort is ...

Cohort study design is described as 'observational' because, unlike clinical studies, there is no intervention. [2] Because exposure is identified before outcome, cohort studies are considered to provide stronger scientific evidence than other observational studies such as case-control studies. [1] A fundamental characteristic of the study ...