Nursing: Family Centered Care

Introduction, the family centered care, reference list.

Family centered care is a practice incorporates the family of a patient to be part of intensive care. The family in this case is the patient’s relatives or people that the patient considers closest to him. Mitchell et al refer to Family Centered Care as [an innovative approach to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care that is grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among health care patients, families, and providers.

Patient and family centered care applies to patients of all ages, and it may be practiced in any health care setting] (Mitchell et al., 2009, 543). Family Centered care therefore is a collaboration of the nurses and the family of the patient to provide intensive care. This collaboration between the family and the nurses results in complete care for the patient. Below is an overview of the Family Centered Care in the Intensive Care Unit.

The patient’s kin play an important role in critical care. They provide information when the patient is unable to speak and make decision for the patients. They are involved in making giving opinions, making, assessing and implementing care. As a result the family centered care benefits the patient. The intensive care “is based on mutual respect, collaboration, and support for the family and the patient” (Mitchell et al 2009, 544).

The family of the patient during intensive care expects that the health providers will notify and assure them of recovery as well as have access to see their relative. Family members who are allowed to assist in giving care ended up with a positive attitude. They assist in giving care even after the patient recovers and is discharged. The patient benefits from the company of the relative. After discharge the patient has an easier time coping with home care given by the relatives, while the relatives cope easily with the giving care.

Furthermore fewer readmission occur (Mitchell et al 2009, 544). According to Gavaghan, family centered care is the key to an all rounded care for intensive care patients. The family receives necessary information in order to support the patient. The nurses on the other hand receive support from the family, while the patient benefits from the intensive care.

In their study, Mitchell et al (2009, 543) observed that there are three indicators of family centered care. They include; respect, collaboration and support. Hennman and Cardin (2002, 65) affirms that the relatives feel respected if they are given information about the patient. The family cares to know the sleeping patterns, the medical procedures the patient is expected to undergo and if the patient is recovering. The family also needs to know when to offer help. This is because they are willing and ready to give support. In this case nurses explain what the family cannot understand, for instance when to let the patient rest. The family needs reassurance. When there is no hope, the family should be informed that the patients comfort is important.

York (2004, 84) found out that health providers have culturally been neglecting the patients family. While the patient is receiving medical attention, the relatives are left in the waiting area without any information. Centrally to that culture, the presence of the kinsmen could have a positive effect. As she further mentions, the family of the patient can alleviate the difficulty of accepting negative results after medical efforts to save life are unsuccessful.

Providing Family centered care is a challenging task. A nurse must practice patience when dealing with the patient and the relatives (Cooley and McAllister, 1999, 121). They should have a positive attitude towards the support to provide intensive care to the patient. Another challenge is the Perceptions about the family. Nurses assume that relatives cause the patient to have stress and therefore time given for visitation is limited.

The nurses see this restriction as a benefit to the patient. This is because they create time for themselves rather than spent a lot of time in the hospital. Nurses should not assume that the presence of a relative on the bedside is an indicator of their inability to work. Also, patients on the other hand should not see the presence of relatives as invasion into their privacy. Instead, they should see it as collective support, to assist them recover. Hennman and Cardin (2002, 64) argue that the important point to consider is to ensure that the patients needs are the determining factor of every action.

In order to ensure that the family centered care is a success there should be some form of regulation. Order can be achieved if there are clearly outlined rules that explain what extend of care the family is allowed to give the patients. There should be a structure that is considerate of the patient, the relatives and the nurses. This will ensure that care is given at the right time, in the right way and by the right person. Information booklets or flyers can be availed to the patient’s relative so that there is understanding amongst them. The importance of this information is to clarify doubts, and states the dos and don’ts. The relatives could be allowed to give feedback in order to improve family centered care (Sisterhen et al., 2007, 319).

Family Centered care contributes to the recovery of a patient through combined efforts. The needs of the patient and the family are met while the nurse gets support in providing care. The patient needs should guide the actions in the family centered care. The end result of this relationship is that the family participates actively in giving support.

Cooley, W. C., & McAllister, J. W. (1999). Putting Family-Centered Care into Practice: A Response to the Adaptive Practice Model . Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics , 20 (2), 120-122.

Gavaghan, S. R. & Carroll, D. L. (2002). Families of critically ill patients and the effect of nursing interventions. Dimensions in Critical Care Nursing , 21 (2), 64-71.

Henneman, E. A. & Cardin, S. (2002). Family-centered critical care: A practical Approach to making it Happen. Critical Care Nurse , 22 (6), 12-19.

Mitchell, M., Chaboyer, W., Burmeister, E., Foster, M. (2009). Positive Effects of Nursing Intervention on Family- Centered Care in Adult Critical Care. American Journal of Critical Care , 18 (2), 543-552.

Sisterhen, L. L., Blaszak, R. T., Woods, M. B. & Smith, C. E. (2007). Defining family-centered rounds. Teaching and Learning in Medicine , 19 (2), 319-322.

York, N. (2004). Implementing a Family Presence Protocol Option . Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing , 23(2), 84-88.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, April 17). Nursing: Family Centered Care. https://studycorgi.com/nursing-family-centered-care/

"Nursing: Family Centered Care." StudyCorgi , 17 Apr. 2022, studycorgi.com/nursing-family-centered-care/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Nursing: Family Centered Care'. 17 April.

1. StudyCorgi . "Nursing: Family Centered Care." April 17, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/nursing-family-centered-care/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Nursing: Family Centered Care." April 17, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/nursing-family-centered-care/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Nursing: Family Centered Care." April 17, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/nursing-family-centered-care/.

This paper, “Nursing: Family Centered Care”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: July 30, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 13 August 2019

Towards a universal model of family centered care: a scoping review

- Kristina M. Kokorelias 1 ,

- Monique A. M. Gignac 2 ,

- Gary Naglie 3 , 4 &

- Jill I. Cameron ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4161-1572 1 , 5

BMC Health Services Research volume 19 , Article number: 564 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

93k Accesses

197 Citations

70 Altmetric

Metrics details

Families play an important role meeting the care needs of individuals who require assistance due to illness and/or disability. Yet, without adequate support their own health and wellbeing can be compromised. The literature highlights the need for a move to family-centered care to improve the well-being of those with illness and/or disability and their family caregivers. The objective of this paper was to explore existing models of family-centered care to determine the key components of existing models and to identify gaps in the literature.

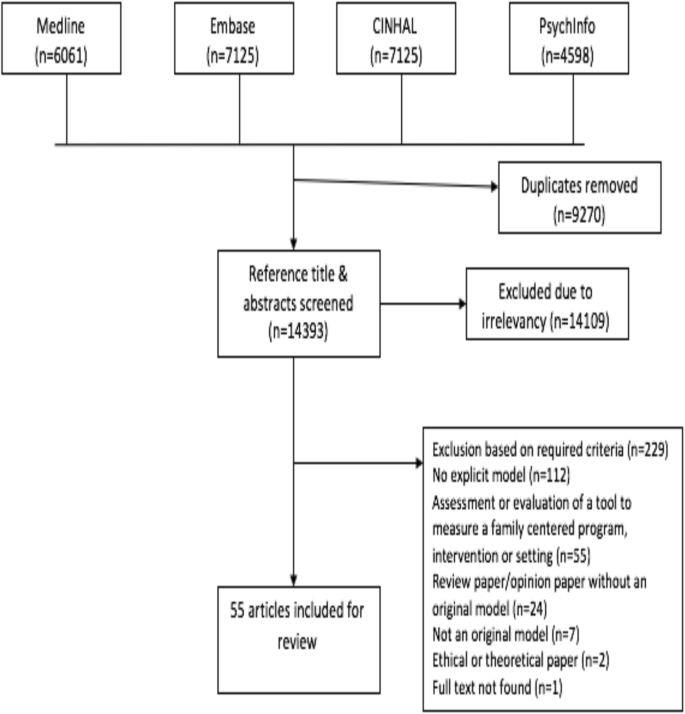

A scoping review guided by Arksey & O’Malley (2005) examined family-centered care models for diverse illness and age populations. We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and EMBASE for research published between 1990 to August 1, 2018. Articles describing the development of a family-centered model in any patient population and/or healthcare field or on the development and evaluation of a family-centered service delivery intervention were included.

The search identified 14,393 papers of which 55 met our criteria and were included. Family-centered care models are most commonly available for pediatric patient populations ( n = 40). Across all family-centered care models, the consistent goal is to develop and implement patient care plans within the context of families. Key components to facilitate family-centered care include: 1) collaboration between family members and health care providers, 2) consideration of family contexts, 3) policies and procedures, and 4) patient, family, and health care professional education. Some of these aspects are universal and some of these are illness specific.

Conclusions

The review identified core aspects of family-centred care models (e.g., development of a care plan in the context of families) that can be applied to all populations and care contexts and some aspects that are illness specific (e.g., illness-specific education). This review identified areas in need of further research specifically related to the relationship between care plan decision making and privacy over medical records within models of family centred care. Few studies have evaluated the impact of the various models on patient, family, or health system outcomes. Findings can inform movement towards a universal model of family-centered care for all populations and care contexts.

Peer Review reports

Families play an integral role providing care to individuals with health conditions. As the number of individuals facing chronic illness continues to rise worldwide, there is a timely need to increase recognition of the care input made by family members. Nearly half of Canadians aged 15 years and older have provided care to persons with illness and/or disabilities [ 1 ]. Definitions of caregivers vary, but in general they are an unpaid family member, close friend, or neighbour who provides assistance with every day activities, including hands-on care, care coordination and financial management [ 2 ]. We use the term caregivers to reflect this definition. We use the term family to include the patient, caregiver(s) and other family members. When caring for patients with progressively deteriorating conditions and increasing care needs, over time, caregivers perform more complex care duties similar to those carried out by professional health or social service providers [ 3 , 4 ]. Thus, caregivers play an important role in the care of persons with illnesses or disability across the entire illness trajectory.

Caregiving can be associated with negative outcomes. Caregivers’ physical and mental health, financial status, and social life are often negatively impacted, regardless of the care recipients’ illness [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. As a result, the quality and sustainability of care provision at home may be threatened [ 5 , 6 ]. Policies and programs to help sustain the caregiving role may reduce the negative consequences of caregiving and optimize care provision in the home.

The need to support caregivers to minimize negative outcomes and optimize the care they provide has received considerable attention in recent policy initiatives. In 2007, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) announced the Aging at Home Strategy, “to enable people to continue leading healthy and independent lives in their own homes” [ 7 ]. The strategy implies a shift away from institutional (e.g., long-term care) care towards home care, using population-based funding allocations to offer health and social services to seniors and their caregivers [ 7 ]. This is similar to initiatives in other provinces, such as British Columbia’s Choice in Supports for Independent Living (CSIL) program, introduced in 1994. As these strategies place increasing demands on caregivers, a broader initiative, the National Carer Strategy launched in 2008 and updated in 2014 articulates the need for universal priorities to support caregivers [ 8 ]. Changes in Canada are echoed in other countries, including Sweden and Vietnam [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. These initiatives aim to facilitate a collaborative action plan to support seniors through policy.

Family-centered care has been proposed to address the needs of not only the patient, but also their family members. To date, family-centered care has been defined by a number of organizations. The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) [ 12 ] defines family-centered care as mutually beneficial partnerships between health care providers (HCPs), patients, and families in health care planning, delivery, and evaluation. Alternatively, Perrin and colleagues [ 13 ] define family-centered care as an organized system of healthcare, education and social services offered to families, that permits coordinated care across systems. In palliative care, family-centered care is defined by Gilmer [ 14 ] as a seamless continuity in addressing patient, family, and community needs related to terminal conditions through interdisciplinary collaboration. In the broadest scope, the notion of family-centred care embraces the view of the care-client as the patient and their family, rather than just the patient [ 14 ].

Building upon existing definitions, models of family-centered care have been proposed for a number of patient populations. The family-centered approach to healthcare delivery, developed most notably for pediatric-care, values a partnership with family members in addressing the medical and psychosocial health of patients. Parents are considered experts concerning their child’s abilities and needs [ 15 , 16 ]. In the context of critical care, family-centered interventions may decrease the strain of caregiving in families during a crisis [ 17 ]. In the context of stroke, a family-centered approach to rehabilitation showed an improvement in adult children caregivers’ depression and health status one-year post stroke [ 18 ]. Other researchers have argued that family-centered care offers an opportunity to support families and strengthen a working partnership between the patient, family, and health professionals during end of life care [ 19 ]. With an aging population and a growing number of people living with chronic illness, family-centered care can help health care systems to provide support and improve quality-of-life, for patients and their families.

To date, there has been no synthesis of key components of original family-centered care models across all illness populations. Therefore, the objective of this paper was to conduct a scoping review of original models of family-centered care to determine the key model components and to identify aspects that are universal across illness populations, and care contexts and aspects that are illness- or care-context specific. This paper also aimed to identify gaps in the literature to provide recommendations for future research. A scoping review was selected as optimum because its goals are to generate a profile of the key concepts in the existing literature on a topic and identify gaps in the literature [ 20 ].

We used a scoping review methodology guided by Arksey & O’Malley [ 21 ] to gather and summarize the existing literature on family-centred care models.

Search strategy

A literature search of MEDLINE (including ePub ahead of print, in process & other non-indexed citations), CINAHL, PSYCHInfo and EMBASE databases was conducted. The search terms “family-centered”, “family-centred” were applied. The search strategy utilized a narrow focus due to the high degree of noise additional keywords generated. All searches were limited to English language publications from 1990 to August 1, 2018. We did not limit the patient population as we believed that the expected number of models in any sub-set of populations would be low. Searches were conducted by an Information Specialist. EndNote was used to organize the literature and assist with removal of duplicates. See Additional file 1 for an example of the search strategy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria.

The focus of the article was on the development and/or evaluation of a family-centered model or a family-centered service delivery intervention

The article considered healthcare providers’ communication/interactions with patients and families

The focus of the article was on the development of a family-centered model in any patient population and/or location of care (i.e., acute care hospital, inpatient rehabilitation, community, institutional long-term care).

For the purposes of this paper, we used The Agency for Clinical Innovation (ACI)‘s definition of a model of care: “the way health services are delivered” ([ 22 ], p., 3). The definition includes where, by whom and how the intervention is delivered.

Exclusion criteria

The focus of the article was an assessment or the evaluation of a tool that measured the degree of family-centeredness of a program, intervention or setting and not the evaluation of an original family-centered care model

The article considered only interactions between family members

The article was a review paper that did not propose an original model of family-centered care

The article pertained primarily to ethical issues or the theoretical understandings of family-centered care

The article was focused on training healthcare providers on how to deliver family-centered care and did not offer an original model of family-centered care.

The article reviewed or discussed only the history, implications or rationale for family-centered care (e.g., the study conclusions suggested the need for a model of family-centered care)

The article described a patient-centered care model that only included discussion of family interactions

The focus of the article was on the development of a family-centered model exclusively for social support, rather than in a clinical, health-care context.

Study selection and charting the data

The search identified 14,393 papers. One of the authors (K.M.K.) reviewed the citations and abstracts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two other individuals reviewed 30% of the retrieved abstracts. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were modified as needed to enhance clarity (final inclusion/exclusion criteria aforementioned). Full-text articles of all potentially relevant references were retrieved, and each was independently assessed for eligibility by one of the authors (K.M.K.) and the two other reviewers. There was 100% concordance between all reviewers on this second step. Reference lists of the included articles were reviewed by one of the authors (K.M.K.) and the two other reviewers, but no additional articles were added to the review.

Data were extracted by the lead author (K.M.K.) and the abstracted data content was reviewed for accuracy by the two other reviewers. Data were extracted relating to elements of the family-centered care model including details of the targeted population, objectives, intervention (if applicable), key findings and desired outcomes of the model. The key components of the models were systematically charted using a data charting form developed in Microsoft Word with a priori categories to guide the data extraction (see Additional file 2 ).

Data synthesis

The purpose of this scoping review was to aggregate the family-centred model descriptions and present an overview of the key elements of the models. Methodological rigour of the publications was not examined, as consistent with scoping review methodologies [ 21 ].

The extracted data were collated to identify key components of models of family-centered care. K.M.K extracted the data and J.I.C reviewed the extracted data. K.M.K and J.I.C then followed qualitative thematic analysis using techniques of scrutinizing, charting and sorting the extracted data according to crucial nuances of the data, and this was summarized into descriptive themes characterizing model components [ 21 , 23 ]. Data were synthesized using summary tables with tentative thematic headings. Themes and potential components of family-centered care models were discussed between K.M.K and J.I.C until consensus was achieved, and final themes were developed. When discussing themes, K.M.K and J.I.C analyzed the data within and then across different patient populations (diagnoses), age groups (pediatric vs. adult literature), and care contexts (e.g., acute care, community care) to identify aspects of models that are universal (i.e., do not differ across populations and care contexts) and aspects that are illness-specific. Final themes were then discussed with all authors. These themes represent answers to our study objective.

Fifty-five articles were included in this review (see Fig. 1 ). The majority of articles were not grounded in empirical research but proposed models for family-centered care and offered practical suggestions to inform implementation (91%). Of the 9 empirical studies, four articles (7%) described randomized control trials (RCTs) and one (2%) described a pre-test, post-test evaluation of their model. Three of the models tested in RCTs were developed to support families at the end of the patients’ lives, with the other model focused on behavioural change as part of childhood obesity treatment. The article describing a pre-test, post-test evaluation aimed to reduce alcohol and drug use through positive peer and family influences. Another study used longitudinal experimental quantitative design to measure the impact of their family-centered care model over two time points, using t-test analysis [ 24 ]. These studies demonstrated benefits of the models including enhanced feelings of mastery and empowerment for family members in care planning through skill building [ 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Search Selection

Two articles (3%) examined the feasibility of applying the concepts of family-centered models into practice. Eight articles (14%) described case studies of an implemented model that included families and children with complex medical needs in palliative and sub-acute settings with conditions including HIV, cancer and stem-cell transplantations. Another described patients and families in cardiac intensive care units (CICU) after operative procedures. Nine (16%) articles were literature reviews on FCC that lead to the description of a single hypothetical family-centered care model, but did not review all existing FCC models. One article (2%) compared HCPs’ roles in traditional models of care with their roles the family-centered model.

Out of the 55 included papers, 40 (73%) were explicitly designed for pediatric care recipients. In the pediatric literature, family-centered care models were proposed for a variety of populations which included, but were not limited to, cancer ( n = 5), AIDS/HIV ( n = 3), motor dysfunction (e.g. cerebral palsy) ( n = 3), non-illness specific disabilities ( n = 2), obesity ( n = 3), asthma ( n = 1), oral disease (1 paper), trauma ( n = 2), autism ( n = 1) and transplant recipients ( n = 1). Eighteen studies did not report on a specific population. In adult populations, models have been presented for palliative care ( n = 3), heart failure ( n = 1), mental health ( n = 1), cancer ( n = 1), age-related chronic conditions ( n = 1) and unspecified populations ( n = 8).

Many of the family-centered care models have been developed for a variety of care contexts (e.g., community, acute care) and incorporate a variety of health care professionals. Care contexts included home/community care, acute hospital wards, emergency departments, critical care units, inpatient rehabilitation units and palliative care units. Professionals identified in the models primarily included nurses, social workers, physicians and nutritionists. In some models, psychologists, rehabilitation therapists and chaplains also were included. The core elements of FCC models did not differ by diagnosis, age or care context. This suggested that some aspects of FCC models were universal. We use the term “universal” to refer to this notion of high-level concepts that can be applied across illness populations, ages and care contexts. Universal and illness-specific aspects of FCC will be discussed in detail below.

Thematic analysis revealed a universal goal of FCC models to develop and implement patient care plans within the context of families. To facilitate this aim, family-centered care models require: 1) collaboration between family members and health care providers, 2) consideration of family contexts, 3) education for patients, families, and HCPs, and 4) dedicated policies and procedures. Figure 2 provides a graphical overview of the key components of FCC. This figure highlights the overarching goal of FCC models and the key components required to help facilitate this goal including both universal and illness-specific components.

Universal Model of Family-Centered Care

Overarching theme: family-centred care plan development and implementation

This overarching theme describes the universal goal of family-centered care models to develop and implement patient care plans that are created within the context of unique family situations.

All 55 models supported the development of family-centered care plans with specific short and long-term outcomes [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Patients, families and HCPs were considered key partners who should contribute to the clarification of care plan goals [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Care plans should consider the day-to-day ways of living for patients and families [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ] by encouraging the maintenance of home routines [ 41 ]. Potential goals identified included achieving family and patient identified functional milestones like a new motor skill (e.g., running) [ 30 ]; decreasing delays or complications at hospital discharge [ 42 ]; improving patient and family satisfaction with care [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]; and improving caregiver support [ 43 ]. Patient involvement in care plans was acknowledged as conditional upon the patient’s capacity to participate (it may exclude young children, people with illnesses affecting their cognition, etc.). From the initial diagnosis, the models championed that all members of the patients care team should elicit families’ perspectives regarding priorities, families’ needs and concerns, and their abilities to provide care [ 14 , 29 , 37 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]. Understanding families’ needs and priorities was deemed important and as contributing to realistic and better-defined outcomes [ 24 , 45 ], as well as important to enhance families’ abilities to support the plan and optimize patient outcomes [ 41 , 49 , 50 , 51 ].

The models also emphasized that HCPs and family members should share in the implementation of the care plan. Care delivery should commence when everyone is in agreement with the care plan [ 42 ]. It was noted that family members should be encouraged to communicate any issues or priorities they have regarding care to HCPs [ 27 , 44 ]. Family members of relatives who are inpatients also should be involved in discharge planning, such as describing their concerns and ability to perform care duties [ 42 ] so as to troubleshoot and optimize care in the community. Some models noted that care plans can be made achievable by breaking them down into smaller steps for the family [ 27 ]. One model also hypothesized that monitoring the success of the care plan has the potential to optimize service use by bridging service gaps and eliminating any duplication of resources [ 52 ].

Model components

In addition to the overarching theme related to care plan development and implementation (described above), other key model components needed to facilitate family-centered care plans were identified. These encompassed collaboration and communication; education and support; consideration of the family context; and the need for policies and procedures.

Collaboration

Family-centered care models highlighted collaboration between HCPs, patients and families as key in the development of care plans. Collaboration was noted as being required across the illness and care trajectory [ 53 ] to enhance patients’ and families’ abilities to maintain control over the patient’s care plan and delivery [ 54 ], particularly as care becomes increasingly complex [ 55 ].

Many of the family-centered care models offered some insight into how families and HCPs could work together in the delivery of care across the care trajectory. Trusting [ 54 ], caring and collaborative relationships [ 44 ] between families and HCPs were identified as key and efforts should be undertaken to cultivate them. In this collaborative relationship, HCPs were encouraged to relinquish their role as a single authority. Some authors even argued that families should have decision-making authority to decide upon the role and the degree of involvement of HCPs in developing care plans [ 28 ]. Attharos and colleagues [ 55 ] further suggested that family-centered care models should have defined roles for each family member, the patient, and all involved HCPs. All roles are essential to the development of care plans [ 56 ].

Communication

Family-centered care models were thought to better facilitate communication and exchange of information and insights among family members, patients and HCPs related to the development and delivery of care plans [ 54 ]. One model suggested that clinicians should offer care options and patients and families should advocate for patient preferences and family values [ 57 ]. The exchange of information was encouraged to be open, timely, complete and objective [ 27 , 55 ].

The models encouraged HCPs to use a variety of strategies to communicate with and support caregivers and patients, including interdisciplinary care and diagnostic reports, community follow-up in-person or by virtual meetings, and resource notebooks listing community supports to help care for the patient [ 29 ]. HCPs were also encouraged to communicate disease-specific information to help patients and family members make appropriately-informed disease-related decisions [ 32 , 39 , 57 ].

Education about care provision and the disease was deemed necessary to enable family-centered care. Education was typically approached from the concept of mutual learning, whereby patients, family members and HCPs all learn and support each other [ 38 , 54 ]. In general, models advocated for training of HCPs to effectively elicit information and communicate with patients and family members. This was thought to decrease anxiety and increase control for patients and caregivers [ 14 , 32 , 58 , 59 ].

Various researchers posited ways to best provide education about the illness and care provision to patients and families. Connor [ 60 ] suggested that written information, describing the family-centered approach to care should be provided to patients and caregivers. Further, all information should be presented at a language level that is understandable to the family and patient [ 42 , 43 , 60 ], which means minimizing technical (e.g., medical) jargon [ 59 ].

Education was though to be ongoing, meaning that it often doesn’t end when a patient is discharged from an inpatient setting. Models highlighted a need to establish methods to continue educating caregivers beyond inpatient care [ 49 ], such as by providing the patient and family with a follow–up care plan after discharge and possibly follow-up contact by HCPs [ 33 ]. Appropriately communicated education is believed to foster a sense of trust [ 42 ] and help patients and family members become more knowledgeable. As a result, patients and families were thought to become more independent in making informed treatment decisions [ 14 , 35 , 37 ].

Some models noted that patients and their family members find it helpful to learn from other patients and caregiver peers [ 32 ]. Peer sharing of mutually supportive resources and other experiences related to living with an illness or providing care can serve as an important means of improving knowledge about support resources [ 32 ] and enhancing emotional support [ 60 , 61 ]. This was thought to be possible as part of family centered care models by care teams helping to cultivate friendships and general peer support with other families in similar caregiving situations (for example, those caring for care recipients with the same illness). Other mechanisms to offer peer support could include patient and caregiver support groups, workshops, group retreat trips, and shared respite care [ 14 ].

Family support needs

Family members may experience a negative impact on their own well-being as part of the ongoing demands of caregiving. Recognizing that families are often psychologically stressed and can have difficulties coping [ 59 ], family-centered care models emphasized support for family members’ well-being [ 62 ]. Supporting families often included emotional support and providing education and training on care delivery that takes into account caregiver needs and preferences. Family-centered models acknowledge that caregivers are experts in matters concerned with their own well-being [ 47 ]. HCPs were thought to support caregivers’ by providing education to foster caregivers’ confidence in their ability to provide care and develop care plans.

Family-centered care models emphasized that care recipients function best in a supportive family environment [ 41 ]. Identifying the impact of the illness on the patient and the family is crucial to providing emotional support [ 42 ]. At a minimum, information about support needs should be gathered from both patient and family [ 63 ]. Particularly in pediatric patient populations, authors spoke of identifying types of support that are based on the patient’s developmental capacities [ 64 ] and needs, while also taking into consideration the social context of the patient and family’s life [ 48 ]. Support needs can be determined through well-designed, semi-structured activities, including questionnaires [ 48 ] and discussions with the family.

Health systems utilizing a family-centered care model were thought to help sustain caregivers by providing them with resources to support their caregiving activities [ 65 ]. Goetz and Caron [ 49 ] state that organizational support should make existing health service community resources more family-centered by considering the family in all aspects of program delivery. Topics that need to be addressed by services offered to family members included, mental health, home care, insurance/financing, transportation, public health, housing, vocational services, education and social services [ 13 ].

Consideration of family context

Family was conceptualized in different ways across models. For example, some models described including the family-as-a-whole (every family member, not just those that provide care) [ 63 , 64 ], whereas others described the family as those who provide care [ 44 ]. Authors highlighted that families have ‘the ultimate responsibility’ [ 63 ] and should have a constant presence throughout the care and illness trajectory [ 60 ]. Consistently across family-centered care models, families were seen as vital members of the care team [ 38 ] who provide emotional, physical, and instrumental levels of support to the patient [ 32 , 54 ].

Family strengths

Three of the models underscored that family-centered care is based on a belief that all families have unique strengths that should be identified, enhanced, and utilized [ 41 , 53 , 66 ]. Models identified various examples of family strengths in care delivery including resilience [ 41 ], coping strategies [ 58 ], competence and skill in providing care [ 25 , 26 ] and motivation [ 49 ]. None of the models discussed how these strengths would be identified when implementing family centered care. Three of the models stated that family-centered care should continuously encourage caregivers to utilize these strengths [ 53 , 57 , 64 ] although specific examples of how to do so were not included. Identifying areas of weakness that may require education and training was not discussed in the models.

Cultural values

Families were thought to contribute to a culturally sensitive care plan by discussing their specific cultural needs, as well as their strengths related to personal values, preferences and ideas. Caregivers’ social, religious, and/or cultural backgrounds can influence the provision of care to their family member [ 29 , 49 , 57 , 58 ]. One model suggested that HCPs need to elicit information about families’ beliefs [ 26 ] to help guide culturally sensitive care plans (e.g. religious participation). The process by which this would occur was not discussed in detail.

Dedicated policies and procedures to support implementation

To support implementation, family-centered care models should have dedicated policies and procedures that are also transparent [ 56 , 67 , 68 ]. Both the macro and micro levels of society need to be considered when trying to implement family-centered practices [ 13 ]. Perrin and colleagues [ 13 ] described macro level issues as including government policies and agencies (e.g., national, provincial, municipal), while micro level factors include community service systems (e.g., physicians, other HCPs, schools, public transportation, etc.). Examples of macro-level considerations include incorporating families in nation-wide policy making and program development [ 29 , 53 , 56 , 60 ]. Micro-level considerations include incorporating family members and patients in decision-making for local community organizations [ 69 ], the implementation of health programs and care policies at regional hospitals, as well as in HCP education [ 29 ].

Family-centered care policies were identified as important as they legitimize and support families’ contributions to the care of their family member. For example, in pediatrics, Regan and colleagues [ 39 ] suggested changing policy to open visitation hours to increase family members’ roles as partners in care. This could increase the number of interactions between HCPs, patients and families, and, as a result, further support caregivers in their caring role [ 24 ].

Family-centered care models also noted the importance of considering the physical environment when developing policies and practices. The physical environment of care settings should be created and tailored to meet the needs of patients and families [ 54 ], although concreate examples were not provided. Both the patient and family should be included in the development and evaluation of facility design [ 29 ], where possible, as well as modifications to the home environment.

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify core components of family-centered care models and to identify components that are universal and can be applied across care populations. This paper also aimed to identify gaps in the literature to provide recommendations for future research. Most models were developed for pediatric populations with a number of models emerging for the care of adult populations. The synthesis suggests that there are core components of family-centered care models that were not unique to specific illness populations or care contexts making them applicable across diverse health conditions and experiences. From a theoretical perspective, our review adds to our understanding of how FCC is conceptualized within the current state of the literature and suggests the possibility of moving towards a universal model of FCC. This includes developing a care plan with defined outcomes and that incorporates patient and family perspectives and their unique characteristics. This also includes collaboration between HCPs and family members and flexible policies and procedures. However, there were some aspects of models that were specific to illness populations such as illness-specific patient and family education.

Currently, person-centered care is considered best practice for improving care and outcomes for many illness populations. Patient-centered care has been described as being “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” [ 70 ]. Person-centered care involves: acknowledging the individuality of persons in all aspects of care, and personalizing care and surroundings; offering shared decision making; interpreting behavior from the person’s viewpoint; and prioritizing relationships to the same extent as care tasks [ 71 ]. Aspects of patient and person-centered care were identified as key components of family-centered care models including focusing on patient and family values, preferences and needs, related to their own circumstances and family contexts. In addition, this review identified specific components that go beyond patient-centered care that are required to address the needs of families including focusing on respectful communication to facilitate the necessary patient/family-professional partnerships and collaboration needed to develop and implement care plans. Moreover, there is the need for the patient/family-professional partnerships to respect the strengths, cultures and expertise that all members of this partnership bring to the development and delivery of care plans.

Implementation of illness-specific models of care for multiple different illnesses may be challenging for health care systems. As many individuals live with multi-morbidity, a non-illness specific family-centered care model may meet the needs of more individuals [ 72 ]. Yet, there is a lack of discussion in the literature of concrete strategies to help implement the key concepts identified in our review. Moreover, the research on implementing FCC models in real world situations is scant. In order to encourage changes in health care systems there is a need for evidence that the concepts of FCC lead to improvements.

This review identified aspects of family-centered care that are illness-specific. Illness-specific education and support is required at each stage of the illness recognizing differences in illness trajectories across patient populations [ 73 ]. Currently, the models are described with static concepts that are not reflective of ongoing and changing illness trajectories. Providing illness-specific care, advice, and information that is sensitive to their place in the illness trajectory may greatly influence caregivers’ capacity to support the care recipient. Further research is needed to understand how family-centered care may evolve across the illness and care trajectory.

More research is needed to enhance the potential of a universal family-centered care model that crosses age groups, conditions, and care settings. For instance, in the current models of FCC, there is not consistent definition of what constitutes the family. In the pediatric literature the family primarily includes the parents of the child, but does not usually include siblings or extended family members who may be providing care. Moreover, current FCC models fail to address conflict and mediation for circumstances where there is the potential for family members to disagree with one another, with the patient or with the HCPs regarding care plans or other aspects of care.

As many of the models were developed for pediatric populations, they fail to acknowledge aspects such as privacy issues and cognitive capacity. These issues become relevant as we consider models of care for adult populations. In instances where patients’ cognitive capacity influences their ability to participate in decision-making, family caregivers become active contributors to care plan development and implementation. Caregivers can benefit from having access to patients’ medical information to contribute to treatment decision making and inform care and service use. Current privacy legislation does not automatically give families access to relevant information. Future research should explore adult patients’ preferences for family members to have access to their medical records, as their preferences will influence the management of privacy in models of FCC.

Lastly, the articles included in this review were primarily descriptive and not evaluative. Evaluations are needed to demonstrate the benefit of FCC to patient, caregiver and health system outcomes. Potential evaluation outcomes can include satisfaction with care, improvements in patient health and caregiver health and stress, and efficient use of health services. There should be consensus regarding outcome measures to be used when evaluating FCC models to enhance our ability to compare across models. Model evaluation is needed to provide empirical evidence to support or reject the concepts of FCC in both universal and illness-specific contexts. Moreover, we need methods to assess implementation of FCC in practice. For example, measures to assess the family-centered nature of care are being developed [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The review suggests we may need new assessment tools to assess, for example, family strengths.

Concrete steps are needed to implement a universal FCC care model into practice. While we have defined the components of a model, we have also highlighted additional empirical research that is needed to further define model components in real-world settings, within and across various care contexts and illness populations. In particular, we recommend the testing of our universal model in the context of a randomized control trial (RCT).

Lastly, we recommend the development of outcomes measures to determine if FCC leads to improvements in patient and family satisfaction, mental and physical health outcomes, enhanced efficiency, health system utilization (e.g., decreased length of hospital stay or return hospital visits), community reintegration and cost-effectiveness. Important outcomes should relate to families, patients of all ages and health care professionals. Outcome measures related to health care professionals may include enhanced comfort working with families and patients. Valid and reliable measures are essential for the evaluation of a model’s effectiveness and to translate FCC models into practice.

Study limitations

This scoping review is not without limitations. Only published, English language articles were included, thus excluding other models that may exist in other languages. This may have also limited models to those that were developed and/or tested in predominantly English-speaking counties. We also did not explore grey literature, limiting our models to only those that underwent peer review. Many of the included models were designed for the pediatric population, so findings have limited application to adult populations.

This paper used an established scoping review methodology to synthesize 55 models of family-centered care. We were able to determine the universal components of the models that place both the patient and family at the center of care, regardless of the patient’s illness or care context. Findings outline aspects of FCC that are universal and aspects that are illness specific. Universal aspects include collaboration between family members and health care providers to define care plans that take into consideration the family contexts. It also includes the need for flexible policies and procedures and the need for patient, family, and health care professional education. Non-universal aspects include illness-specific patient and family education. Future research should evaluate the ability of FCC to improve important patient, family, caregiver, and health system outcomes. Health care policies and procedures are needed that incorporate FCC to create system level change. Our review moves the field of FCC forward by identifying the universal and illness-specific model components that can inform model development, testing, and implementation. Advancing FCC has the potential to optimize outcomes for patients, families, and caregivers.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Family-centered care

Health care professionals

Sinha M. Portrait of caregivers, 2012. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2013. Retrieved from: http://healthcareathome.ca/mh/en/Documents/Portrait%20of%20Caregivers%202012.pdf

Google Scholar

Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):217.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schulz R, Martire LM. Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):240–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Collins LG, Swartz K. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(11):1309.

PubMed Google Scholar

Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–55.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Government of Canada. Canada Health Act [“CHA”], R.S.C. 1985, c. C-6. Ottawa, Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20031205153216/http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/C-6/

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario's Aging at Home Strategy. Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/ program/ltc/33_ontario_strategy.html

Carers Canada. Canada’s Carer strategy. Ottawa. Retrieved from: http://www.carerscanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CC-Caregiver-Strategy_v4.pdf .

Feinberg LF, Newman SL. A study of 10 states since passage of the National Family Caregiver Support Program: policies, perceptions, and program development. The Gerontologist. 2004;44(6):760–9.

Hokenstad MC Jr, Restorick RA. International policy on ageing and older persons: implications for social work practice. Int Soc Work. 2011;54(3):330–43.

Article Google Scholar

Sweden Report, Supra note 20, sat 9; social services act, SFS 2001:453, promulgated June 7, 2001, online: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Sweden.

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. What is patient- and family-centered care? Available at: http://www.ipfcc.org/about/pfcc.html

Perrin JM, Romm D, Bloom SR, Homer CJ, Kuhlthau KA, Cooley C, Duncan P, Roberts R, Sloyer P, Wells N, Newacheck P. A family-centered, community-based system of services for children and youth with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(10):933–6.

Gilmer MJ. Pediatric palliative care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2002;14(2):207–14.

MacKean G, Spragins W, L’Heureux L, Popp J, Wilkes C, Lipton H. Advancing family-centred care in child and adolescent mental health. A critical review of the literature. Healthc Q. 2012;15:64–75.

Chu S, Reynolds F. Occupational therapy for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), part 2: a multicentre evaluation of an assessment and treatment package. Br J Occup Ther. 2007;70(10):439–48.

Johnson SK, Craft M, Titler M, Halm M, Kleiber C, Montgomery LA, Megivern K, Nicholson A, Buckwalter K. Perceived changes in adult family members' roles and responsibilities during critical illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1995;27(3):238–43.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Visser-Meily A, Post M, Gorter JW, Berlekom SB, Van Den Bos T, Lindeman E. Rehabilitation of stroke patients needs a family-centred approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(24):1557–61.

Teno JM, Casey VA, Welch LC, Edgman-Levitan S. Patient-focused, family-centered end-of-life medical care: views of the guidelines and bereaved family members. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2001;22(3):738–51.

Gagliardi AR, Berta W, Kothari A, Boyko J, Urquhart R. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):38.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

The Agency for Clinical Innovation (ACI). Understanding the process to develop a Model of Care: An ACI Framework. A practical guide on how to develop a Model of Care . 2013 May [cited 2018 April 27]. Available from: https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/181935/HS13-034_Framework-DevelopMoC_D7.pdf

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Marcenko MO, Smith LK. The impact of a Fmaily-centered case management approach. Soc Work Health Care. 1992;17(1):87–100.

Kissane D. Family focused grief therapy: the role of the family in preventive and therapeutic bereavement care. Bereave Care. 2003;22(1):6–8.

Kissane D, Lichtenthal WG, Zaider T. Family care before and after bereavement. Omega. 2008;56(1):21–32.

Leviton A, Mueller M, Kauffman C. The family-centered consultation model: practical applications for professionals. Infants Young Child. 1992;4(3):1–8.

Sharifah WW, Nur HH, Ruzita AT, Roslee R, Reilly JJ. The Malaysian childhood obesity treatment trial (MASCOT). Malays J Nutr. 2011;17(2):229–36.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Jasovsky DA, Morrow MR, Clementi PS, Hindle PA. Theories in action and how nursing practice changed. Nurs Sci Q. 2010 Jan;23(1):29–38.

Darrah J, Law M, Pollock N. Family-centered functional therapy-a choice for children with motor dysfunction. Infants Young Child. 2001;13(4):79–87.

Dowling J, Vender J, Guilianelli S, Wang B. A model of family-centered care and satisfaction predictors: the critical care family assistance program. Chest. 2005;128(3):81S–92S.

Madigan CK, Donaghue DD, Carpenter EV. Development of a family liaison model during operative procedures. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1999;24(4):185–9.

Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, Smith CE. Defining family-centered rounds. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):319–22.

Hyman D. Reorganizing health systems to promote best practice medical care, patient self-management, and family-centered care for childhood asthma. Ethnicity & disease. 2003;13(3 Suppl 3):S3–94.

Kaufman J. Case management services for children with special health care needs. A family-centered approach. J Case Manag. 1992;1(2):53–6.

Prelock PA, Beatson J, Contompasis SH, Bishop KK. A model for family-centered interdisciplinary practice in the community. Top Lang Disord. 1999;19(3):36–51.

Cormany EE. Family-centered service coordination: a four-tier model. Infants Young Child. 1993;6(2):12–9.

King G, Tucker MA, Baldwin P, Lowry K, Laporta J, Martens L. A life needs model of pediatric service delivery: services to support community participation and quality of life for children and youth with disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2002;22(2):53–77.

Regan KM, Curtin C, Vorderer L. Paradigm shifts in inpatient psychiatric care of children: approaching child-and family-centered care. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2006;19(1):29–40.

McKlindon D, Barnsteiner JH. Therapeutic relationships: evolution of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia model. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1999;24(5):237–43.

Romero-Daza N, Ruth A, Denis-Luque M, Luque JS. An alternative model for the provision of services to hiV-positive orphans in Haiti. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(4):36–40.

Muething SE, Kotagal UR, Schoettker PJ, del Rey JG, DeWitt TG. Family-centered bedside rounds: a new approach to patient care and teaching. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):829–32.

Raina P, O'Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J, Walter SD, Russell D, Swinton M, Zhu B, Wood E. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e626–36.

Hernandez LP, Lucero E. Days La Familia community drug and alcohol prevention program: family-centered model for working with inner-city Hispanic families. J Prim Prev. 1996;16(3):255–72.

MacFarlane MM. Family centered care in adult mental health: developing a collaborative interagency practice. J Fam Psychother. 2011;22(1):56–73.

Mausner S. Families helping families: an innovative approach to the provision of respite care for families of children with complex medical needs. Soc Work Health Care. 1995;21(1):95–106.

Biggert RA, Watkins JL, Cook SE. Home infusion service delivery system model: a conceptual framework for family-centered care in pediatric home care delivery. J Intraven Nurs. 1992;15(4):210–8.

Prizant BM, Wetherby AM, Rubin E, Laurent AC. The SCERTS model: a transactional, family-centered approach to enhancing communication and socioemotional abilities of children with autism spectrum disorder. Infants Young Child. 2003;16(4):296–316.

Goetz DR, Caron W. A biopsychosocial model for youth obesity: consideration of an ecosystemic collaboration. Int J Obes. 1999;23(S2):S58.

Byers JF. Holistic acute care units: partnerships to meet the needs of the chronically I11 and their families. AACN Adv Crit Care. 1997;8(2):271–9.

CAS Google Scholar

Law M, Darrah J, Pollock N, King G, Rosenbaum P, Russell D, Palisano R, Harris S, Armstrong R, Watt J. Family-centred functional therapy for children with cerebral palsy: an emerging practice model. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 1998;18(1):83–102.

Brady MT, Crim L, Caldwell L, Koranyi K. Family-centered care: a paradigm for care of the HIV-affected family. Pediatr AIDS HIV Infect. 1996;7(3):168–75.

Tyler DO, Horner SD. Family-centered collaborative negotiation: a model for facilitating behavior change in primary care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2008;20(4):194–203.

Brown K, Mace SE, Dietrich AM, Knazik S, Schamban NE. Patient and family–centred care for pediatric patients in the emergency department. CJEM. 2008;10(1):38–43.

Attharos T. Development of a family-centered care model for the children with cancer in a pediatric cancer unit. Thailand: Mahidol University; 2003.

Baker JN, Barfield R, Hinds PS, Kane JR. A process to facilitate decision making in pediatric stem cell transplantation: the individualized care planning and coordination model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(3):245–54.

Lyon ME, Garvie PA, Briggs L, He J, McCarter R, D'Angelo LJ. Development, feasibility, and acceptability of the family/adolescent-centered (FACE) advance care planning intervention for adolescents with HIV. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):363–72.

Beers LS, Cheng TL. When a teen has a tot: a model of care for the adolescent parent and her child: you can mitigate the health and educational risks faced by an adolescent parent and her child by providing a medical home for both. This" teen-tot" model of family-centered care provides a framework for success. Contemp Pediatr. 2006;23(4):47–52.

Callahan HE. Families dealing with advanced heart failure: a challenge and an opportunity. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2003;26(3):230–43.

Connor D. Family-centred care in practice. Nurs N Z. 1998;4(4):18.

Martin-Arafeh JM, Watson CL, Baird SM. Promoting family-centered care in high risk pregnancy. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 1999;13(1):27–42.

Tluczek A, Zaleski C, Stachiw-Hietpas D, Modaff P, Adamski CR, Nelson MR, Reiser CA, Ghate S, Josephson KD. A tailored approach to family-centered genetic counseling for cystic fibrosis newborn screening: the Wisconsin model. J Genet Couns. 2011;20(2):115–28.

Kavanagh KT, Tate NP. Models to promote medical health care delivery for indigent families: computerized tracking to case management. J Health Soc Policy. 1990;2(1):21–34.

Ainsworth F. Family centered group care practice: model building. In Child and youth care forum 1998 Feb 1 (Vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 59-69). Kluwer Academic Publishers-Human Sciences Press.

Ahmann E, Bond NJ. Promoting normal development in school-age children and adolescents who are technology dependent: a family centered model. Pediatr Nurs. 1992;18(4):399–405.

Grebin B, Kaplan SC. Toward a pediatric subacute care model: clinical and administrative features. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(12):SC16–20.

Kazak AE. Comprehensive care for children with cancer and their families: a social ecological framework guiding research, practice, and policy. Child Serv Soc Policy Res Pract. 2001;4(4):217–33.

Davison KK, Lawson HA, Coatsworth JD. The family-centered action model of intervention layout and implementation (FAMILI) the example of childhood obesity. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(4):454–61.

Monahan DJ. Assessment of dementia patients and their families: an ecological-family-centered approach. Health Soc Work. 1993;18(2):123–31.

Reid Ponte PR, Peterson K. A patient-and family-centered care model paves the way for a culture of quality and safety. Crit Care Nurs Clin. 2008;20(4):451–64.

Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, Lindseth A, Norberg A, Brink E, Carlsson J, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Johansson IL, Kjellgren K, Lidén E. Person-centered care—ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(4):248–51.

Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. The European journal of general practice. 2008;14(sup1):28–32.

Cameron JI, Gignac MA. “Timing it right”: a conceptual framework for addressing the support needs of family caregivers to stroke survivors from the hospital to the home. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(3):305–14.

Download references

Acknowledgements

G. Naglie is supported by the George, Margaret and Gary Hunt Family Chair in Geriatric Medicine, University of Toronto.

We would like to thank and acknowledge the contributions of Jessica Babineau, Information Specialist at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute - University Health Network, for providing guidance on the search strategy development, and conducting the literature search.

We would like to thank and acknowledge the contributions of Jazmine Que. and John Nguyen, Masters of Occupational Therapy Students- The University of Toronto, for reviewing subsets of the retrieved articles and extracted study data.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Rehabilitation Sciences Institute, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, 500 University Avenue, Suite 160, Toronto, ON, Canada

Kristina M. Kokorelias & Jill I. Cameron

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Institute for Work and Health, University of Toronto, 481 University Avenue, Suite 800, Toronto, ON, Canada

Monique A. M. Gignac

Department of Medicine and Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, 3560 Bathurst Street, Room 278, Kimel Family Building, Toronto, ON, Canada

Gary Naglie

Department of Medicine, and Affiliated Scientist, Rotman Research Institute, Baycrest Health Sciences, 3560 Bathurst Street, Room 278, Kimel Family Building, Toronto, ON, Canada

Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, Rehabilitation Sciences Institute, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, 500 University Avenue, Suite 160, Toronto, ON, Canada

Jill I. Cameron

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KMK and JIC conceptualised and designed the study. KMK, JIC, GN and MAMG contributed to the interpretation of the data and to the drafting of the initial and revised manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jill I. Cameron .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Search Strategy Example (Medline). (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 2:

Data Abstraction. (DOCX 90 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kokorelias, K.M., Gignac, M.A.M., Naglie, G. et al. Towards a universal model of family centered care: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 19 , 564 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4394-5

Download citation

Received : 14 February 2019

Accepted : 01 August 2019

Published : 13 August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4394-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Family centered care

- Family caregiving

- Patient-care

- Patient education

- Scoping review

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Nursing: Family Centered Care

Introduction.

The information should be accurate between the patient, family members, and the care providers to ensure that quality service is offered.

The care providers need to learn about family background and culture and traditions. This will enable them to create a conducive environment for the health care workers

Much attention can be given to patients in critical conditions if they are near their family members. They will also enjoy the freedom to follow their taste and preferences unlike in hospital-based care where the management determines the diet

It will also enable the care providers to identify the possible barriers that can hinder effective service delivery

It is different from the traditional health care system in that it involves both the patient and the family in deriving a solution to the medical problem (Sisterhen et al 2007, p2).

Literature review

The practice of FCC ensures that both the patient and family are considered as the units of health care (Mitchell, Burmeister, and Foster 2009, p3). The health assurance and well-being of the patients in a critical care environment are affected by the good relationships obtained through the partnership between the family and the professionals.

The strengths, culture, and traditions in a given family will directly impact how a patient relates to the family

These barriers could be those that prevent the patients and families from enjoying such services. They could be those preventing the care providers from effectively delivering their services, e.g. a strange culture and tradition

Sharing the information among the family, the patients, and the professionals will enable health assurance since an appropriate resolution can be made that suits everyone.

The care given under partnership will help reduce the burden that would be put on the health care providers.

There is a need to outline the kind of care that is to be given to the patient and give a description of the delivery process

There is also a need to examine the possible interventions that can be made to meet the needs of both the patients and their families

Family-centered care should be given the necessary precautions to achieve its desired objective. A well-delivered FCC shall ensure that the intended quality services are given to the patients and their families.

Fundamentals of FCC philosophy

There are various key elements of Family-centered care (Cooley & McAllister 1999, p120). The elements can be broadly grouped into these three categories. These are the fundamental principles that govern an effective family-centered care practice. Each of the parties involved should respect and recognize the roles that each has in providing the needed care ( Marshall et al 2002, p2). There should be no overdependence on one party and neither should a party, particularly the staff, consider it wrong for the other to be involved.

The information on the medical history of the patients as well as the economic needs of the family will greatly affect the course of treatment to be provided. Such information should therefore be welcomed by the hospital staff and the family should also be willing to provide it

The care, especially in an ICU environment, should be considered a collective responsibility that requires the services of both parties.

Learning Model

The learning model outlines how the learning process shall be conducted and what is required of the instructor and the learner

The learners should understand the necessities in a learning environment and ensure that they comply with such provisions.

The Adult Learning Theory

The Adult Learning Theory assumes that the learners are very mature people, and who have gained some knowledge in the past. The basics are therefore not very necessary

Interactive learning enables the instructor to identify what the learners are not getting correctly and make clarification appropriately.

The adult learners often have other engagements and it will be very necessary that the learners, as well as the instructor, keep time.

There is a need to have penalties for non-compliance with the learning principles like time management. Specify the consequences of lateness and stress on the dangers of being a passive learner

Interventions to Meet the Needs of the Patients

A patient in a critical condition may lose the courage to ever get better. Words of encouragement from the family members may not sound like truth to such a patient who may have been bedridden for long or underwent amputation in the leg. The nurses are responsible for restoring this lost confidence in the patients

In a situation where there are conflicts in the course of action to be taken about the patient’s care, the nurses should have an upper say to protect the patient. This is because they understand the physiological needs of the body better than the families do

Interventions to Meet the Needs of the Families of the Patient

An important need by the family that should be addressed is the assurance that their patient would recover (Gavaghan & Carroll 2002, p3). The nurses should help the families in identifying their strengths and weaknesses and the possible causes of barriers that can be encountered in providing FCC services. The next move is to assist them to develop these strengths while attempting to alleviate the weaknesses

The assessment of how the family understands the physiological and physical bodily mechanisms will enable the nurses to make an appropriate decision in response to the information that is obtained from the family.

The family of the patient is often interested in knowing the condition of the patient and whether an improvement is recorded or not Gavaghan & Carroll 2002, p3).

Teaching the family the normal physiological functioning of the body will enable them to make an informed decision. They shall be taking a course of action whose purpose and ultimate consequences are well known to them.

The family members should be aware of the important role that they should play in ensuring that their patient receives quality care services.

The beliefs and culture in a given area can affect the people’s perception of the practice of FCC. The nurses should therefore examine such cultural practices and educate the families on the dangers of being stuck to them, especially in a situation that requires crucial medical attention.

Barriers to the Family-Centered Care

The delivery of family-centered care has several challenges that it faces and still allows for the adoption of the traditional system of care. Some of these obstacles stem from within the healthcare center while others are from the families of the patients

The factors could be obstacles to either the professionals who would wish to provide quality services or to the patients and families who would want to obtain the quality services.

Barriers to the patient and family

In practicing family-centered care, there may be a resolution that the family members be close to the patient if the latter has to be hospitalized. The space that is available in the hospital may not allow for that, hence this shall be a barrier.

The infrastructural facilities in the hospital, as well as the entire region, will greatly affect the delivery of family-centered care services. If the patients are being nursed at home, poor conditions of the roads may not allow the professionals who have limited time to assess the patients’ progress effectively. Other facilities like water and electricity will greatly affect the necessary care given to the patients, especially in critical conditions.

Some professionals find it professionally unethical to involve the opinions of the patients and their families in addressing the issues that concern the patient’s health. The patients and family needs will thus not be considered in decision making posing challenges to an effective FCC

The patients and families are maybe not aware of the need to have such a kind of care system. They then adopt the traditional system that it is the professional who knows what to do and should be fully responsible for the steps to be taken.

They may also be unaware of the services even though they may be practiced in a given center.

Lack of enough resources in the patients family can be of absolute threat to effective family-centered care

Barriers to the Professionals

The ratio of physicians to patients is growing smaller and smaller with the increasing number of patients that need attention. The average physician time per patient is thus a scarce resource that may not allow for family-centered care. Financial constraints may also not allow for the physicians to effectively deliver the services at home.

Barriers on the Professionals Cont’

A care provider would be positively willing to practice FCC, however, if such a program is not supported by the management then the professional may not effectively deliver the services. It is the responsibility of the management of a health institution to ensure that such services are instituted and supported

The nurses should be conversant with the cultural beliefs and practices in a given community from which the patient hails. Some communities do not believe in medical treatment. An important guideline is to help the family and patient understand and appreciate the effectiveness of health care systems (MacDougall 2007, p1)

A care provider may fail to collaborate with a given family due to the conflicting cultural beliefs and practices that exist between them

The data about the lab results, admission and discharge dates, and chart reviews are not easy to keep in practice family-centered care. This will eventually pose a problem when attempting to evaluate how such practices progress to make the necessary improvements.

Creating Conducive Environment

Creating a conducive environment for the delivery of family-centered care is mainly concerned with the management of the health institution. They are the interventions that the staff need to make to ensure the effective delivery of FCC (Bowden & Greenberg 2009, p10) They need to have a positive attitude towards the service.

They should do away with what is referred to as ‘latent conditions’ characterized by the poor environment with the administration not intending to make changes (Reiling, Hughes & Murphy n.d, p1).

The expansion of accommodation facilities will allow for more members of the family to be present at the patient’s bedside when there is a need for it.

Alternating the visiting hours will also allow for more members of the family to be present at a patient’s bedside during the visiting time.

The family members who are accommodated to support their patient should be provided with incentives to make him feel at home. Involvement in the activities like sports will enable the family to overcome the stress of nursing their beloved member

The conferences shall enlighten the family on the health matters and enable them to make an informed decision concerning their patient’s needs.

Consistent means of communication will ensure that the family and the hospital are in touch all the time. Any emergency case can then be dealt with immediately.

The family needs to be introduced into the institution. They should be made to feel part of the institution for whatever period it will turn out to be.

It is important to understand that the families that shall be met come from different cultural backgrounds. The nurses should be conversant with the cultures and allow them as long as they are consistent with the regulations of the institution on such issues. Religious culture should not be discouraged since a kind of divine intervention is often required in a critical health condition