How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Q uality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

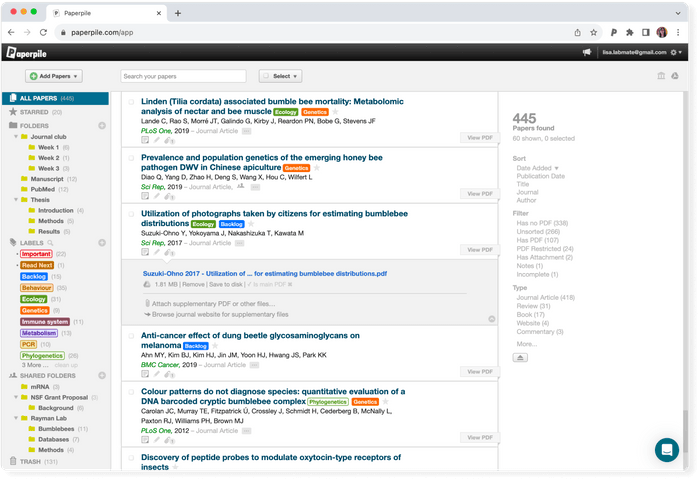

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

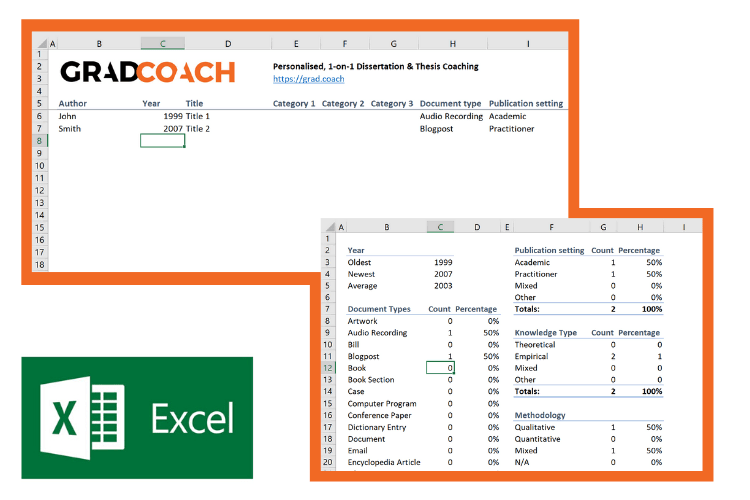

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Learn More About Lit Review:

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

5 Signs You Need A Dissertation Helper

Discover the 5 signs that suggest you need a dissertation helper to get unstuck, finish your degree and get your life back.

Writing A Literature Review: 4 Time-Saving Hacks

🎙️ PODCAST: Ace The Literature Review 4 Time-Saving Tips To Fast-Track Your Literature...

Research Question 101: Everything You Need To Know

Learn what a research question is, how it’s different from a research aim or objective, and how to write a high-quality research question.

Research Question Examples: The Perfect Starting Point

See what quality research questions look like across multiple topic areas, including psychology, business, computer science and more.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Writing a Literature Review

When writing a research paper on a specific topic, you will often need to include an overview of any prior research that has been conducted on that topic. For example, if your research paper is describing an experiment on fear conditioning, then you will probably need to provide an overview of prior research on fear conditioning. That overview is typically known as a literature review.

Please note that a full-length literature review article may be suitable for fulfilling the requirements for the Psychology B.S. Degree Research Paper . For further details, please check with your faculty advisor.

Different Types of Literature Reviews

Literature reviews come in many forms. They can be part of a research paper, for example as part of the Introduction section. They can be one chapter of a doctoral dissertation. Literature reviews can also “stand alone” as separate articles by themselves. For instance, some journals such as Annual Review of Psychology , Psychological Bulletin , and others typically publish full-length review articles. Similarly, in courses at UCSD, you may be asked to write a research paper that is itself a literature review (such as, with an instructor’s permission, in fulfillment of the B.S. Degree Research Paper requirement). Alternatively, you may be expected to include a literature review as part of a larger research paper (such as part of an Honors Thesis).

Literature reviews can be written using a variety of different styles. These may differ in the way prior research is reviewed as well as the way in which the literature review is organized. Examples of stylistic variations in literature reviews include:

- Summarization of prior work vs. critical evaluation. In some cases, prior research is simply described and summarized; in other cases, the writer compares, contrasts, and may even critique prior research (for example, discusses their strengths and weaknesses).

- Chronological vs. categorical and other types of organization. In some cases, the literature review begins with the oldest research and advances until it concludes with the latest research. In other cases, research is discussed by category (such as in groupings of closely related studies) without regard for chronological order. In yet other cases, research is discussed in terms of opposing views (such as when different research studies or researchers disagree with one another).

Overall, all literature reviews, whether they are written as a part of a larger work or as separate articles unto themselves, have a common feature: they do not present new research; rather, they provide an overview of prior research on a specific topic .

How to Write a Literature Review

When writing a literature review, it can be helpful to rely on the following steps. Please note that these procedures are not necessarily only for writing a literature review that becomes part of a larger article; they can also be used for writing a full-length article that is itself a literature review (although such reviews are typically more detailed and exhaustive; for more information please refer to the Further Resources section of this page).

Steps for Writing a Literature Review

1. Identify and define the topic that you will be reviewing.

The topic, which is commonly a research question (or problem) of some kind, needs to be identified and defined as clearly as possible. You need to have an idea of what you will be reviewing in order to effectively search for references and to write a coherent summary of the research on it. At this stage it can be helpful to write down a description of the research question, area, or topic that you will be reviewing, as well as to identify any keywords that you will be using to search for relevant research.

2. Conduct a literature search.

Use a range of keywords to search databases such as PsycINFO and any others that may contain relevant articles. You should focus on peer-reviewed, scholarly articles. Published books may also be helpful, but keep in mind that peer-reviewed articles are widely considered to be the “gold standard” of scientific research. Read through titles and abstracts, select and obtain articles (that is, download, copy, or print them out), and save your searches as needed. For more information about this step, please see the Using Databases and Finding Scholarly References section of this website.

3. Read through the research that you have found and take notes.

Absorb as much information as you can. Read through the articles and books that you have found, and as you do, take notes. The notes should include anything that will be helpful in advancing your own thinking about the topic and in helping you write the literature review (such as key points, ideas, or even page numbers that index key information). Some references may turn out to be more helpful than others; you may notice patterns or striking contrasts between different sources ; and some sources may refer to yet other sources of potential interest. This is often the most time-consuming part of the review process. However, it is also where you get to learn about the topic in great detail. For more details about taking notes, please see the “Reading Sources and Taking Notes” section of the Finding Scholarly References page of this website.

4. Organize your notes and thoughts; create an outline.

At this stage, you are close to writing the review itself. However, it is often helpful to first reflect on all the reading that you have done. What patterns stand out? Do the different sources converge on a consensus? Or not? What unresolved questions still remain? You should look over your notes (it may also be helpful to reorganize them), and as you do, to think about how you will present this research in your literature review. Are you going to summarize or critically evaluate? Are you going to use a chronological or other type of organizational structure? It can also be helpful to create an outline of how your literature review will be structured.

5. Write the literature review itself and edit and revise as needed.

The final stage involves writing. When writing, keep in mind that literature reviews are generally characterized by a summary style in which prior research is described sufficiently to explain critical findings but does not include a high level of detail (if readers want to learn about all the specific details of a study, then they can look up the references that you cite and read the original articles themselves). However, the degree of emphasis that is given to individual studies may vary (more or less detail may be warranted depending on how critical or unique a given study was). After you have written a first draft, you should read it carefully and then edit and revise as needed. You may need to repeat this process more than once. It may be helpful to have another person read through your draft(s) and provide feedback.

6. Incorporate the literature review into your research paper draft.

After the literature review is complete, you should incorporate it into your research paper (if you are writing the review as one component of a larger paper). Depending on the stage at which your paper is at, this may involve merging your literature review into a partially complete Introduction section, writing the rest of the paper around the literature review, or other processes.

Further Tips for Writing a Literature Review

Full-length literature reviews

- Many full-length literature review articles use a three-part structure: Introduction (where the topic is identified and any trends or major problems in the literature are introduced), Body (where the studies that comprise the literature on that topic are discussed), and Discussion or Conclusion (where major patterns and points are discussed and the general state of what is known about the topic is summarized)

Literature reviews as part of a larger paper

- An “express method” of writing a literature review for a research paper is as follows: first, write a one paragraph description of each article that you read. Second, choose how you will order all the paragraphs and combine them in one document. Third, add transitions between the paragraphs, as well as an introductory and concluding paragraph. 1

- A literature review that is part of a larger research paper typically does not have to be exhaustive. Rather, it should contain most or all of the significant studies about a research topic but not tangential or loosely related ones. 2 Generally, literature reviews should be sufficient for the reader to understand the major issues and key findings about a research topic. You may however need to confer with your instructor or editor to determine how comprehensive you need to be.

Benefits of Literature Reviews

By summarizing prior research on a topic, literature reviews have multiple benefits. These include:

- Literature reviews help readers understand what is known about a topic without having to find and read through multiple sources.

- Literature reviews help “set the stage” for later reading about new research on a given topic (such as if they are placed in the Introduction of a larger research paper). In other words, they provide helpful background and context.

- Literature reviews can also help the writer learn about a given topic while in the process of preparing the review itself. In the act of research and writing the literature review, the writer gains expertise on the topic .

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

- UCSD Library Psychology Research Guide: Literature Reviews

External Resources

- Developing and Writing a Literature Review from N Carolina A&T State University

- Example of a Short Literature Review from York College CUNY

- How to Write a Review of Literature from UW-Madison

- Writing a Literature Review from UC Santa Cruz

- Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149. doi : 1371/journal.pcbi.1003149

1 Ashton, W. Writing a short literature review . [PDF]

2 carver, l. (2014). writing the research paper [workshop]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Research Paper Structure

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a literature review in 6 steps

What is a literature review?

How to write a literature review, 1. determine the purpose of your literature review, 2. do an extensive search, 3. evaluate and select literature, 4. analyze the literature, 5. plan the structure of your literature review, 6. write your literature review, other resources to help you write a successful literature review, frequently asked questions about writing a literature review, related articles.

A literature review is an assessment of the sources in a chosen topic of research.

A good literature review does not just summarize sources. It analyzes the state of the field on a given topic and creates a scholarly foundation for you to make your own intervention. It demonstrates to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.

In a thesis, a literature review is part of the introduction, but it can also be a separate section. In research papers, a literature review may have its own section or it may be integrated into the introduction, depending on the field.

➡️ Our guide on what is a literature review covers additional basics about literature reviews.

- Identify the main purpose of the literature review.

- Do extensive research.

- Evaluate and select relevant sources.

- Analyze the sources.

- Plan a structure.

- Write the review.

In this section, we review each step of the process of creating a literature review.

In the first step, make sure you know specifically what the assignment is and what form your literature review should take. Read your assignment carefully and seek clarification from your professor or instructor if needed. You should be able to answer the following questions:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What types of sources should I review?

- Should I evaluate the sources?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or critique sources?

- Do I need to provide any definitions or background information?

In addition to that, be aware that the narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good overview of the topic.

Now you need to find out what has been written on the topic and search for literature related to your research topic. Make sure to select appropriate source material, which means using academic or scholarly sources , including books, reports, journal articles , government documents and web resources.

➡️ If you’re unsure about how to tell if a source is scholarly, take a look at our guide on how to identify a scholarly source .

Come up with a list of relevant keywords and then start your search with your institution's library catalog, and extend it to other useful databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Science.gov

➡️ Our guide on how to collect data for your thesis might be helpful at this stage of your research as well as the top list of academic search engines .

Once you find a useful article, check out the reference list. It should provide you with even more relevant sources. Also, keep a note of the:

- authors' names

- page numbers

Keeping track of the bibliographic information for each source will save you time when you’re ready to create citations. You could also use a reference manager like Paperpile to automatically save, manage, and cite your references.

Read the literature. You will most likely not be able to read absolutely everything that is out there on the topic. Therefore, read the abstract first to determine whether the rest of the source is worth your time. If the source is relevant for your topic:

- Read it critically.

- Look for the main arguments.

- Take notes as you read.

- Organize your notes using a table, mind map, or other technique.

Now you are ready to analyze the literature you have gathered. While your are working on your analysis, you should ask the following questions:

- What are the key terms, concepts and problems addressed by the author?

- How is this source relevant for my specific topic?

- How is the article structured? What are the major trends and findings?

- What are the conclusions of the study?

- How are the results presented? Is the source credible?

- When comparing different sources, how do they relate to each other? What are the similarities, what are the differences?

- Does the study help me understand the topic better?

- Are there any gaps in the research that need to be filled? How can I further my research as a result of the review?

Tip: Decide on the structure of your literature review before you start writing.

There are various ways to organize your literature review:

- Chronological method : Writing in the chronological method means you are presenting the materials according to when they were published. Follow this approach only if a clear path of research can be identified.

- Thematic review : A thematic review of literature is organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time.

- Publication-based : You can order your sources by publication, if the way you present the order of your sources demonstrates a more important trend. This is the case when a progression revealed from study to study and the practices of researchers have changed and adapted due to the new revelations.

- Methodological approach : A methodological approach focuses on the methods used by the researcher. If you have used sources from different disciplines that use a variety of research methods, you might want to compare the results in light of the different methods and discuss how the topic has been approached from different sides.

Regardless of the structure you chose, a review should always include the following three sections:

- An introduction, which should give the reader an outline of why you are writing the review and explain the relevance of the topic.

- A body, which divides your literature review into different sections. Write in well-structured paragraphs, use transitions and topic sentences and critically analyze each source for how it contributes to the themes you are researching.

- A conclusion , which summarizes the key findings, the main agreements and disagreements in the literature, your overall perspective, and any gaps or areas for further research.

➡️ If your literature review is part of a longer paper, visit our guide on what is a research paper for additional tips.

➡️ UNC writing center: Literature reviews

➡️ How to write a literature review in 3 steps

➡️ How to write a literature review in 30 minutes or less

The goal of a literature review is to asses the state of the field on a given topic in preparation for making an intervention.

A literature review should have its own independent section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where it can be found, and address this section as “Literature Review.”

There is no set amount of words for a literature review; the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, then it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, then it will be short.

Most research papers include a literature review. By assessing the available sources in your field of research, you will be able to make a more confident argument about the topic.

Literature reviews are most commonly found in theses and dissertations. However, you find them in research papers as well.