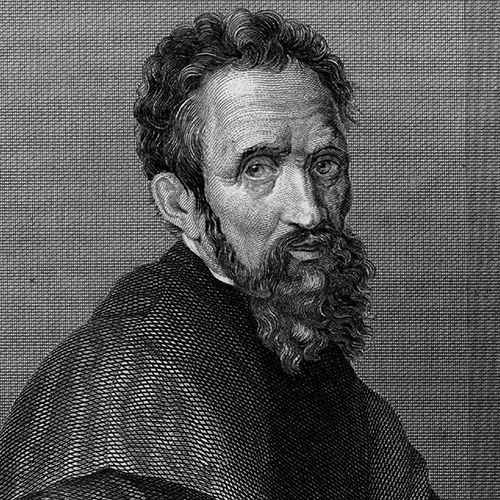

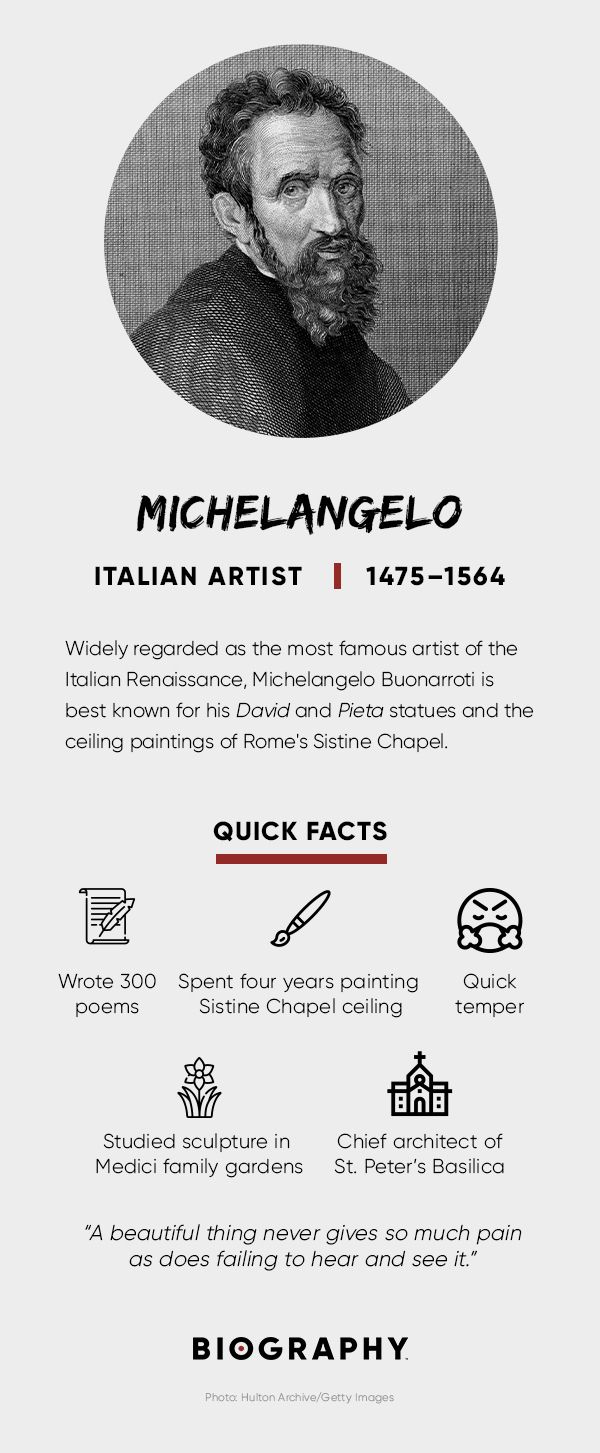

Michelangelo Biography

Born on March 6, 1475, in a town near Arezzo, in Tuscany, Michelangelo lived a comfortable life during his childhood. His family were bankers in Florence, but his father decided to enter a government post when the bank industry failed. When he was born, his father served as the judicial administrator at Caprese, as well as Chiusi's local administrator. Eventually, Michelangelo's family went back to Florence, and this was where the artist lived much of his childhood. In 1481, his mother died of a chronic illness, and he was only 6 years of age at that time. The artist came to Florence, so he could study grammar under his master Francesco da Urbino. However, he was vaguely interested in formal schooling, as he was more fascinated with copying paintings from various churches in Italy. He was also able to meet several painters who inspired him to pursue his art education.

Life in Florence

At that time, Florence was considered as the center of learning and arts throughout Italy. The town council sponsored art, along with wealthy patrons, banking associates and merchant guilds. Moreover, the Renaissance was flourishing in this Italian city, which gave rise to impressive structures and artistic masterpieces. At 13 years old, Michelangelo obtained apprenticeship from Ghirlandaio. A year after, the artist's father asked Ghirlandaio to pay Michelangelo as an artist, and this was a rather unusual circumstance during that time. In 1489, a wealthy man and Florence's de facto ruler named Lorenzo de Medici asked Ghirlandaio for two of his best pupils. Without hesitation, he recommended Francesco Granacci and Michelangelo. Hence, the young artist was given a chance to be enrolled in the Humanist Academy, an institution founded by the Medici. While studying at the academy, Michelangelo realized that his outlook and works were rather influenced by numerous writers and philosophers in history such as Pico della Mirandola, Poliziano and Marsilio Ficino. It was also during this period that the artist began sculpting some of his renowned works including the Battle of the Centaurs and Madonna of the Steps . Poliziano suggested the theme Battle of the Centaurs, and this artwork was commissioned by Lorenzo de Medici.

Accomplishments

When Lorenzo died in 1492, this caused some challenges and uncertainties in the life of Michelangelo. He was forced to leave the security of living and earning money at the Medici court, and he came back to his father's house. A few months after, he was able to make a wooden crucifix, which he gave as a present to the prior of the Santa Maria del Santo Spirito. The said prior gave the artist a chance to study the anatomy of some of the corpses found at the church's hospital. By 1493, he decided to buy a marble that he could use for a life-size statue of Hercules, which was eventually sent to France. The artist was given another chance to re-enter the Medici court in 1494, and this was the time when Piero de Medici commissioned from him a snow statue. During the same year that the artist came back to the court, the Medici had to leave Florence because of the rise of Savonarola. Michelangelo, however, left the city even before the political crisis started. He relocated to Venice before proceeding to Bologna, where he was tasked to complete the carving of some small figures found at the Shrine and tomb of St. Dominic. Before 1494 ended, he traveled back to Florence during the time Charles VIII were experiencing defeats and Florence was in a stable condition. While in Florence, the artist became preoccupied with his latest projects such as the statue of a sleeping Cupid and the child St. John the Baptist.

Life in Rome

At 21 years of age, the artist came to Rome where he engaged in new projects. On July 4, 1496, he began sculpting the massive statue of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine. Cardinal Raffaele Riario commissioned him to do this project, but he eventually rejected the artist's work. Afterward, the statue was bought by Jacopo Galli, a wealthy banker. In 1497, the French Ambassador in Rome commissioned Michelangelo's work called the Pieta. Although the artist was very much devoted to his sculpting, he became deeply interested in drawing and painting. In fact, while in Rome, he completed several artworks that made him one of the most popular artists in his time.

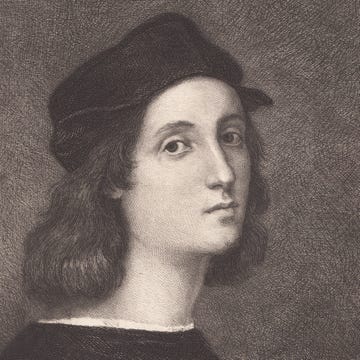

Later in Michelangelo's life, he was able to create several Pietas, which reflects different images. The Pieta of Vittoria Colonna, for instance, was a chalk drawing that presented Mary with upraised arms and hands, which indicated her prophetic role. As for the frontal features of the image, it resembled the fresco by Masaccio, which is found at the Holy Trinity in Santa Maria Novella, in Florence. As for the Florentine Pieta, the artist depicted himself as the old image of Nicodemus as he lowered Jesus' body upon his death on the cross. Mary Magdalene and Mary, the mother of Jesus, were also included in this Pieta . It can be found that the leg and left arm of Jesus in this Pieta was smashed, which was said to have been done by Michelangelo. Eventually, the disfigured arm and leg were repaired by Tiberio Calcagni, the artist's pupil. According to scholars, the Rondanini Pieta was Michelangelo's final work, yet it remains unfinished because he started working on it until there was a lack of stone to complete the work. Hence, this work of art maintained an abstract quality that resembled the 20th century concept and style of sculpting. Along with Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael , and Donatello , Michelangelo was responsible for sixteenth century Florence becoming the century of a movement of artists that has permanently enriched western culture. Considered as one of the leading lights of the Italian Renaissance , Michelangelo was without a doubt one of the most inspirational and talented artists in modern history.

Sistine Chapel Ceiling

The last judgment, the creation of adam, the deposition, creation of the sun, moon, and plants, madonna of bruges, the battle of cascina, the torment of saint anthony, risen christ.

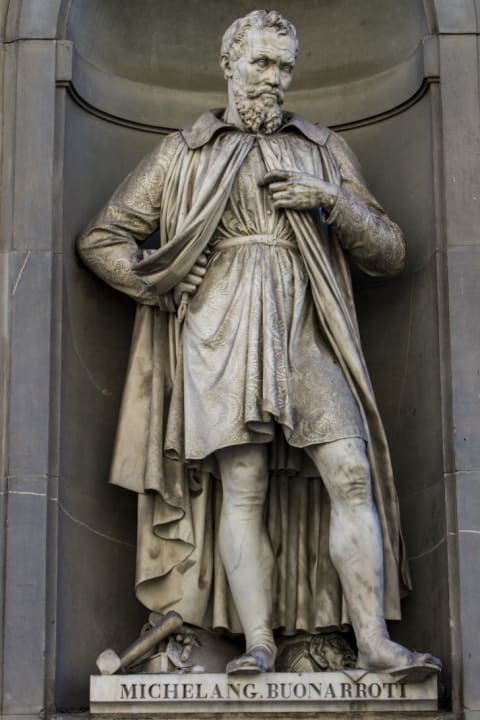

Michelangelo

Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo created the 'David' and 'Pieta' sculptures and the Sistine Chapel and 'Last Judgment' paintings.

(1475-1564)

Who Was Michelangelo?

Michelangelo Buonarroti was a painter, sculptor, architect and poet widely considered one of the most brilliant artists of the Italian Renaissance . Michelangelo was an apprentice to a painter before studying in the sculpture gardens of the powerful Medici family .

What followed was a remarkable career as an artist, famed in his own time for his artistic virtuosity. Although he always considered himself a Florentine, Michelangelo lived most of his life in Rome, where he died at age 88.

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy, the second of five sons.

When Michelangelo was born, his father, Leonardo di Buonarrota Simoni, was briefly serving as a magistrate in the small village of Caprese. The family returned to Florence when Michelangelo was still an infant.

His mother, Francesca Neri, was ill, so Michelangelo was placed with a family of stonecutters, where he later jested, "With my wet-nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues."

Indeed, Michelangelo was less interested in schooling than watching the painters at nearby churches and drawing what he saw, according to his earliest biographers (Vasari, Condivi and Varchi). It may have been his grammar school friend, Francesco Granacci, six years his senior, who introduced Michelangelo to painter Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Michelangelo's father realized early on that his son had no interest in the family financial business, so he agreed to apprentice him, at the age of 13, to Ghirlandaio and the Florentine painter's fashionable workshop. There, Michelangelo was exposed to the technique of fresco (a mural painting technique where pigment is placed directly on fresh, or wet, lime plaster).

Medici Family

From 1489 to 1492, Michelangelo studied classical sculpture in the palace gardens of Florentine ruler Lorenzo de' Medici of the powerful Medici family. This extraordinary opportunity opened to him after spending only a year at Ghirlandaio’s workshop, at his mentor’s recommendation.

This was a fertile time for Michelangelo; his years with the family permitted him access to the social elite of Florence — allowing him to study under the respected sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni and exposing him to prominent poets, scholars and learned humanists.

He also obtained special permission from the Catholic Church to study cadavers for insight into anatomy, though exposure to corpses had an adverse effect on his health.

These combined influences laid the groundwork for what would become Michelangelo's distinctive style: a muscular precision and reality combined with an almost lyrical beauty. Two relief sculptures that survive, "Battle of the Centaurs" and "Madonna Seated on a Step," are testaments to his phenomenal talent at the tender age of 16.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MICHELANGELO FACT CARD

Move to Rome

Political strife in the aftermath of Lorenzo de' Medici’s death led Michelangelo to flee to Bologna, where he continued his study. He returned to Florence in 1495 to begin work as a sculptor, modeling his style after masterpieces of classical antiquity.

There are several versions of an intriguing story about Michelangelo's famed "Cupid" sculpture, which was artificially "aged" to resemble a rare antique: One version claims that Michelangelo aged the statue to achieve a certain patina, and another version claims that his art dealer buried the sculpture (an "aging" method) before attempting to pass it off as an antique.

Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio bought the "Cupid" sculpture, believing it as such, and demanded his money back when he discovered he'd been duped. Strangely, in the end, Riario was so impressed with Michelangelo's work that he let the artist keep the money. The cardinal even invited the artist to Rome, where Michelangelo would live and work for the rest of his life.

Personality

Though Michelangelo's brilliant mind and copious talents earned him the regard and patronage of the wealthy and powerful men of Italy, he had his share of detractors.

He had a contentious personality and quick temper, which led to fractious relationships, often with his superiors. This not only got Michelangelo into trouble, it created a pervasive dissatisfaction for the painter, who constantly strived for perfection but was unable to compromise.

He sometimes fell into spells of melancholy, which were recorded in many of his literary works: "I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts," he once wrote.

In his youth, Michelangelo had taunted a fellow student, and received a blow on the nose that disfigured him for life. Over the years, he suffered increasing infirmities from the rigors of his work; in one of his poems, he documented the tremendous physical strain that he endured by painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Political strife in his beloved Florence also gnawed at him, but his most notable enmity was with fellow Florentine artist Leonardo da Vinci , who was more than 20 years his senior.

Poetry and Personal Life

Michelangelo's poetic impulse, which had been expressed in his sculptures, paintings and architecture, began taking literary form in his later years.

Although he never married, Michelangelo was devoted to a pious and noble widow named Vittoria Colonna, the subject and recipient of many of his more than 300 poems and sonnets. Their friendship remained a great solace to Michelangelo until Colonna's death in 1547.

Soon after Michelangelo's move to Rome in 1498, the cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, a representative of the French King Charles VIII to the pope, commissioned "Pieta," a sculpture of Mary holding the dead Jesus across her lap.

Michelangelo, who was just 25 years old at the time, finished his work in less than one year, and the statue was erected in the church of the cardinal's tomb. At 6 feet wide and nearly as tall, the statue has been moved five times since, to its present place of prominence at St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City.

Carved from a single piece of Carrara marble, the fluidity of the fabric, positions of the subjects, and "movement" of the skin of the Piet — meaning "pity" or "compassion" — created awe for its early viewers, as it does even today.

It is the only work to bear Michelangelo’s name: Legend has it that he overheard pilgrims attribute the work to another sculptor, so he boldly carved his signature in the sash across Mary's chest. Today, the "Pieta" remains a universally revered work.

Between 1501 and 1504, Michelangelo took over a commission for a statue of "David," which two prior sculptors had previously attempted and abandoned, and turned the 17-foot piece of marble into a dominating figure.

The strength of the statue's sinews, vulnerability of its nakedness, humanity of expression and overall courage made the "David" a highly prized representative of the city of Florence.

Originally commissioned for the cathedral of Florence, the Florentine government instead installed the statue in front of the Palazzo Vecchio. It now lives in Florence’s Accademia Gallery .

Sistine Chapel

Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo to switch from sculpting to painting to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which the artist revealed on October 31, 1512. The project fueled Michelangelo’s imagination, and the original plan for 12 apostles morphed into more than 300 figures on the ceiling of the sacred space. (The work later had to be completely removed soon after due to an infectious fungus in the plaster, then recreated.)

Michelangelo fired all of his assistants, whom he deemed inept, and completed the 65-foot ceiling alone, spending endless hours on his back and guarding the project jealously until completion.

The resulting masterpiece is a transcendent example of High Renaissance art incorporating the symbology, prophecy and humanist principles of Christianity that Michelangelo had absorbed during his youth.

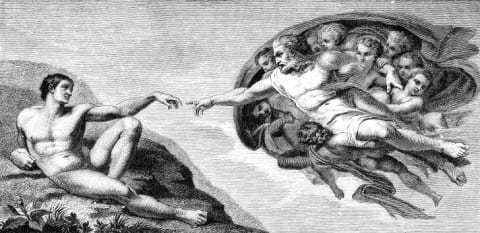

'Creation of Adam'

The vivid vignettes of Michelangelo's Sistine ceiling produce a kaleidoscope effect, with the most iconic image being the " Creation of Adam," a famous portrayal of God reaching down to touch the finger of man.

Rival Roman painter Raphael evidently altered his style after seeing the work.

'Last Judgment'

Michelangelo unveiled the soaring "Last Judgment" on the far wall of the Sistine Chapel in 1541. There was an immediate outcry that the nude figures were inappropriate for so holy a place, and a letter called for the destruction of the Renaissance's largest fresco.

The painter retaliated by inserting into the work new portrayals: his chief critic as a devil and himself as the flayed St. Bartholomew.

Architecture

Although Michelangelo continued to sculpt and paint throughout his life, following the physical rigor of painting the Sistine Chapel he turned his focus toward architecture.

He continued to work on the tomb of Julius II, which the pope had interrupted for his Sistine Chapel commission, for the next several decades. Michelangelo also designed the Medici Chapel and the Laurentian Library — located opposite the Basilica San Lorenzo in Florence — to house the Medici book collection. These buildings are considered a turning point in architectural history.

But Michelangelo's crowning glory in this field came when he was made chief architect of St. Peter's Basilica in 1546.

Was Michelangelo Gay?

In 1532, Michelangelo developed an attachment to a young nobleman, Tommaso dei Cavalieri, and wrote dozens of romantic sonnets dedicated to Cavalieri.

Despite this, scholars dispute whether this was a platonic or a homosexual relationship.

Michelangelo died on February 18, 1564 — just weeks before his 89th birthday — at his home in Macel de'Corvi, Rome, following a brief illness.

A nephew bore his body back to Florence, where he was revered by the public as the "father and master of all the arts." He was laid to rest at the Basilica di Santa Croce — his chosen place of burial.

Unlike many artists, Michelangelo achieved fame and wealth during his lifetime. He also had the peculiar distinction of living to see the publication of two biographies about his life, written by Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi.

Appreciation of Michelangelo's artistic mastery has endured for centuries, and his name has become synonymous with the finest humanist tradition of the Renaissance.

Watch "Michelangelo: Artist and Man" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Michelangelo Buonarroti

- Birth Year: 1475

- Birth date: March 6, 1475

- Birth City: Caprese (Republic of Florence)

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo created the 'David' and 'Pieta' sculptures and the Sistine Chapel and 'Last Judgment' paintings.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Michelangelo was just 25 years old at the time when he created the 'Pieta' statue.

- For the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo fired all of his assistants and painted the 65-foot ceiling alone.

- Despite his immense talent, Michelangelo had a quick temper and contempt for authority.

- Death Year: 1564

- Death date: February 18, 1564

- Death City: Rome

- Death Country: Italy

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Michelangelo Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/michelangelo

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 4, 2020

- Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I accomplish.

- I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

- I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts.

- With my wet-nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues.

- A beautiful thing never gives so much pain as does failing to hear and see it.

- Faith in oneself is the best and safest course.

- If people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn't seem so wonderful at all.

- Critique by creating.

- The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

- With few words I will make thee understand my soul.

- Lord, make me see thy glory in every place.

- Genius is eternal patience.

- If you knew how much work went into it, you wouldn't call it genius.

Famous Painters

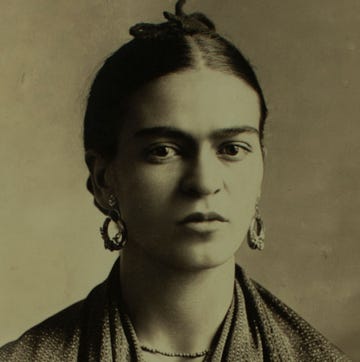

Frida Kahlo

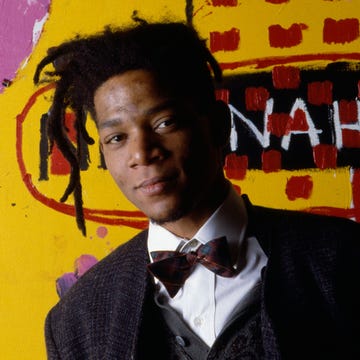

Jean-Michel Basquiat

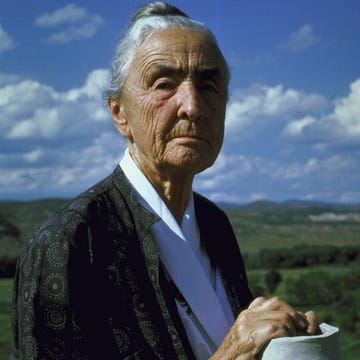

Georgia O'Keeffe

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Michelangelo

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 6, 2019 | Original: October 18, 2010

Michelangelo was a sculptor, painter and architect widely considered to be one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance—and arguably of all time. His work demonstrated a blend of psychological insight, physical realism and intensity never before seen. His contemporaries recognized his extraordinary talent, and Michelangelo received commissions from some of the most wealthy and powerful men of his day, including popes and others affiliated with the Catholic Church. His resulting work, most notably his Pietà and David sculptures and his Sistine Chapel paintings, has been carefully tended and preserved, ensuring that future generations would be able to view and appreciate Michelangelo’s genius.

Early Life and Training

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni) was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy. His father worked for the Florentine government, and shortly after his birth his family returned to Florence, the city Michelangelo would always consider his true home.

Did you know? Michelangelo received the commission to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling as a consolation prize of sorts when Pope Julius II temporarily scaled back plans for a massive sculpted memorial to himself that Michelangelo was to complete.

Florence during the Italian Renaissance period was a vibrant arts center, an opportune locale for Michelangelo’s innate talents to develop and flourish. His mother died when he was 6, and initially his father initially did not approve of his son’s interest in art as a career.

At 13, Michelangelo was apprenticed to painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, particularly known for his murals. A year later, his talent drew the attention of Florence’s leading citizen and art patron, Lorenzo de’ Medici , who enjoyed the intellectual stimulation of being surrounded by the city’s most literate, poetic and talented men. He extended an invitation to Michelangelo to reside in a room of his palatial home.

Michelangelo learned from and was inspired by the scholars and writers in Lorenzo’s intellectual circle, and his later work would forever be informed by what he learned about philosophy and politics in those years. While staying in the Medici home, he also refined his technique under the tutelage of Bertoldo di Giovanni, keeper of Lorenzo’s collection of ancient Roman sculptures and a noted sculptor himself. Although Michelangelo expressed his genius in many media, he would always consider himself a sculptor first.

Sculptures: The Pieta and David

Michelangelo was working in Rome by 1498 when he received a career-making commission from the visiting French cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, envoy of King Charles VIII to the pope. The cardinal wanted to create a substantial statue depicting a draped Virgin Mary with her dead son resting in her arms—a Pieta—to grace his own future tomb. Michelangelo’s delicate 69-inch-tall masterpiece featuring two intricate figures carved from one block of marble continues to draw legions of visitors to St. Peter’s Basilica more than 500 years after its completion.

Michelangelo returned to Florence and in 1501 was contracted to create, again from marble, a huge male figure to enhance the city’s famous Duomo, officially the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. He chose to depict the young David from the Old Testament of the Bible as heroic, energetic, powerful and spiritual and literally larger than life at 17 feet tall. The sculpture, considered by scholars to be nearly technically perfect, remains in Florence at the Galleria dell’Accademia , where it is a world-renowned symbol of the city and its artistic heritage.

Paintings: Sistine Chapel

In 1505, Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to sculpt a grand tomb with 40 life-size statues, and the artist began work. But the pope’s priorities shifted away from the project as he became embroiled in military disputes and his funds became scarce, and a displeased Michelangelo left Rome (although he continued to work on the tomb, off and on, for decades).

However, in 1508, Julius called Michelangelo back to Rome for a less expensive, but still ambitious painting project: to depict the 12 apostles on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel , a most sacred part of the Vatican where new popes are elected and inaugurated.

Instead, over the course of the four-year project, Michelangelo painted 12 figures—seven prophets and five sibyls (female prophets of myth)—around the border of the ceiling and filled the central space with scenes from Genesis.

Critics suggest that the way Michelangelo depicts the prophet Ezekiel—as strong yet stressed, determined yet unsure—is symbolic of Michelangelo’s sensitivity to the intrinsic complexity of the human condition. The most famous Sistine Chapel ceiling painting is the emotion-infused The Creation of Adam, in which God and Adam outstretch their hands to one another.

Architecture & Poems

The quintessential Renaissance man, Michelangelo continued to sculpt and paint until his death, although he increasingly worked on architectural projects as he aged: His work from 1520 to 1527 on the interior of the Medici Chapel in Florence included wall designs, windows and cornices that were unusual in their design and introduced startling variations on classical forms.

Michelangelo also designed the iconic dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (although its completion came after his death). Among his other masterpieces are Moses (sculpture, completed 1515); The Last Judgment (painting, completed 1534); and Day, Night, Dawn and Dusk (sculptures, all completed by 1533).

Later Years

From the 1530s on, Michelangelo wrote poems; about 300 survive. Many incorporate the philosophy of Neo-Platonism—that a human soul, powered by love and ecstasy, can reunite with an almighty God—ideas that had been the subject of intense discussion while he was an adolescent living in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s household.

After he left Florence permanently in 1534 for Rome, Michelangelo also wrote many lyrical letters to his family members who remained there. The theme of many was his strong attachment to various young men, especially aristocrat Tommaso Cavalieri. Scholars debate whether this was more an expression of homosexuality or a bittersweet longing by the unmarried, childless, aging Michelangelo for a father-son relationship.

Michelangelo died at age 88 after a short illness in 1564, surviving far past the usual life expectancy of the era. A pieta he had begun sculpting in the late 1540s, intended for his own tomb, remained unfinished but is on display at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence—not very far from where Michelangelo is buried, at the Basilica di Santa Croce .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Michelangelo

ARTISTS (1475–1564); CAPRESE, ITALY

Michelangelo—full name Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni—is often regarded as one of the most impactful artists of the Renaissance period, creating notable works such as the statues of David and Pietà , and his paintings in the Sistine Chapel, including The Creation of Adam on its ceiling and The Last Judgment behind the church altar. Learn more about the artist below.

1. Michelangelo’s statue of David was originally going to be located on a Florence rooftop.

When the city of Florence first commissioned Michelangelo to sculpt David , it was supposed to be one of many statues to line the roof of the Florence Cathedral dome . But the statue was so well-received when it was completed in 1504 that it was decided that it needed to be more visible to people. Plus, at 17 feet tall and weighing 6.4 tons, moving it onto the roof wouldn’t have been an easy task.

The decision was then made to display it outside the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence’s government offices, where it stood for nearly 370 years before moving to the Galleria dell'Accademia (the Gallery of the Academy of Florence) in 1873, which is where he still stands today.

2. Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment painting may contain a self-portrait of the artist.

In addition to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel , Michelangelo also did a fresco painting on the altar wall of the church, which he worked on from 1536 to 1541. The painting depicts the second coming of Jesus and the judgment of souls going to heaven or hell. It’s generally believed that the artist snuck a reference to himself into the painting; a likeness of Michelangelo can reportedly be seen in the flayed skin of St. Bartholomew, who himself was skinned alive.

3. Michelangelo’s Pietà statue is the artist’s only work to feature his signature.

Pietà , which depicts Mary cradling the body of Jesus after the Crucifixion, is one of Michelangelo’s best-known works. The sculpture is notable beyond just being a masterpiece from the artist—it’s also reportedly the only work Michelangelo ever signed . So what made Michelangelo's Pietà so different from his other works that he just had to sign it? Apparently, he overheard onlookers admiring the statue as a work in progress, but when one of them asked who the artist was, someone in the group attributed it to a different sculptor.

Michelangelo, horrified by the onlooker’s mixup, returned to the statue one night and chiseled his name across Mary’s chest—an act he would later regret and led him to vow that he would never sign another piece of work.

4. Michelangelo’s Moses Sculpture Was Meant for a Much Larger Tomb for Pope Julius II.

Moses is considered one of the artist’s finest works, acting as the main piece for the tomb of Pope Julius II. But while the tomb in its present state is impressive, it was originally meant to be much larger. Pope Julius II, who commissioned the work while he was still alive, meant for his final resting place to be a three-level work, with up to 40 life-sized statues potentially adorning it.

However, other projects, like the Sistine Chapel ceiling, got in the way—but not before Moses was sculpted with the original plans in mind. Following the pope’s death in 1513, Michelangelo agreed to sculpt a much more toned-down tomb, which is where the statue presently stands. Some evidence of the original ideas exist, though, including illustrations of the plans and statues like the Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave , which were planned for the larger design but then wound up in the Louvre in Paris when the plans changed.

5. It took four years for Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Consisting of 300 figures and taking up more than 12,000 square feet, Michelangelo’s sprawling painting on the Sistine Chapel ceiling was a massive undertaking, so it should come as no surprise that it took four years for the artist to finish. Other artists contributed work on the chapel walls, including Sandro Botticelli, Cosimo Rosselli, and Pietro Perugino.

6. Contrary to popular belief, Michelangelo did not paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling while lying on his back.

Despite being a prominent part of Michelangelo’s mythology, the artist did not paint the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling while on his back. In reality, he and his team had constructed a special scaffold to allow him to finish his masterpiece while remaining vertical. Chock the whole thing up to a mistranslation, stemming from a Michelangelo biography by a bishop named Paolo Giovio, where he used the word resupinus , meaning “bent backward,” to talk about the artist’s painting position . Some made the mistake of interpreting that as meaning “on his back,” which is where the idea of a horizontal Michelangelo originated.

7. Michelangelo didn’t consider himself a very talented painter.

The Sistine Chapel ceiling is one of the most celebrated artistic feats in history, but during the whole ordeal, Michelangelo expressed that he had no faith in his ability as a painter. The project left him anxious and paranoid, believing he was being set up to fail. “I’m not in a good place, and I’m no painter,” he famously wrote about the project. While the anxiety may have been there, Michelangelo actually convinced Pope Julius II to expand the scope of the work early on. What was originally supposed to be a painting of the 12 apostles turned into the grand scene you see today.

8. Florence’s Piazzale Michelangelo square has bronze copies of the artist’s most famous sculptures.

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475 in Caprese, Italy, and he passed away after a brief illness on February 18, 1564 in Macel de'Corvi, Rome at the age of 88. And in modern-day Florence, his legacy is now a permanent fixture. This is highlighted by the Piazzale Michelangelo, a popular lookout named after the artist that’s just across from the Arno River that offers panoramic views of the city. As a dedication to Michelangelo and his works, some of his most famous statues—including David and the four allegorical statues from Medici Chapel ( Dawn , Dusk , Night , and Day )—are recreated in bronze and placed around the square.

9. Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam may feature a hidden image of the brain.

In 1990, a physician from Indiana named Dr. Frank Lynn Meshberger came up with a new interpretation of The Creation of Adam , which is the most recognizable portion of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. His theory is that the rose-colored fabric that surrounds God and Eve in the painting represents the human brain, due to its distinct shape. He also pointed to other details that can be found within, such as a green scarf standing in for the vertebral artery and an angel’s foot and leg forming what looks like the pituitary stalk and gland.

Famous Michelangelo Artwork:

- The Creation of Adam (The Sistine Chapel)

- The Last Judgment (The Sistine Chapel)

- Moses (Tomb of Pope Julius II)

- Madonna of Bruges

- The Torment of Saint Anthony

- The Crucifixion of St. Peter

Famous Michelangelo Quotes:

- "Love takes me captive; beauty binds my soul; pity and mercy with their gentle eyes wake in my heart a hope that cannot cheat." (From his poem "Doom of Beauty.")

- "A man paints with his brains and not with his hands."

- "My stomach's squashed under my chin, my beard's pointing at heaven, my brain's crushed in a casket, my breast twists like a harpy's. My brush, above me all the time, dribbles paint so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!" ( Translated from his poem "When the Author Was Painting the Vault of the Sistine Chapel," which was about the agony of painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling.)