- Stories & videos

- My life then and now

- People We Love

Then and now: My life growing up in poverty

- by Cindy L., CI grad, Colombia

Then: A childhood of poverty

My childhood was difficult, because my parents separated when I was just 2. My father went to Barranquilla, Colombia, leaving my mother very sick.

Our economic situation wasn’t the best. [My mother] would take me every morning with her to her friends’ house where she would help them do the chores. As payment, they would give us food. Later, she worked as a maid with the condition that they would let her be with me. That’s how she took care of my needs. My maternal grandmother also supported us.

We lived in a community without many opportunities and with problems with safety, violence and sanitation.

What I remember with great admiration was the care and love that my mother always expressed to me, no matter what she was going through. I always yearned for the love of my father.

When I was 5, Children International came to my community. They enrolled me, and soon an angel appeared and sponsored me. Such happiness!

When I received my first gift, I was excited. Up until then, I didn’t know how important Children International would be in my life.

I happily received all of the gifts. As with the medical and dental care, the medicines were always available. All of that made me feel better and more secure.

This support and the love of my family helped make achieving my dreams easier. Seeing the sacrifices my mother made gave me the strength to keep moving forward and be able to change my life story. I always wanted to be a nurse, and Children International helped me to make that dream a reality.

Smile time: “Although I have a daughter and I’m a single mother, I can take care of her needs and help my mother,” explains Cindy happily.

Now: A dream come true

Thanks to God and Children International for giving me the opportunity to study through a HOPE education scholarship, now I’m a nursing assistant. I stood out as the best student because I really wanted it and I wanted to improve more and more each day.

Currently, I’m working as a nursing assistant for the second consecutive year. I feel really happy to have had Children International’s help, because they contributed to the realization of my dreams.

I was in the youth program. I participated in the workshops which really strengthened me. I learned that we can overcome [issues] if we really want to — that poverty can be overcome, to value ourselves as people, to have a life project and to set goals for ourselves. I had a lot of fun playing, sharing in group, being tolerant and responsible.

This program helped me clarify my goals and strive to achieve them, no matter the difficulties that get in the way.

Having studied nursing and practicing it, means changing my life story — a story full of love, but also with many economic necessities.

Now my life is different. Although I have a daughter and I’m a single mother, I can take care of her needs and help my mother. My future goal is to continue on with becoming a professional in my career, to offer my daughter a good future, never forgetting to give her love. To help my family, my mother, my stepfather (who gave me a father’s love) and my siblings from whom I have always received unconditional love and who give me the strength to move forward.

My dream: become a head nurse or teacher of young children.

I want to serve people and work with boys and girls.

Thank you, Children International and sponsors. God bless you.

Photos and reporting assistance by Marelvis Campo, CI field reporter – Barranquilla.

- Thought Leadership

Children International builds partnerships at UN General Assembly

- by CHRISTINA BECHERER, Senior Director of Global Partnerships

- Team Impact

- Global Perspectives

- Philippines

Reducing educational barriers by boosting literacy

- by Deron D. , Jackson S. and Leo G.

Sponsorship = growth & new beginnings for children

- by Deron D. , and Patricia C.

This site uses cookies to improve your experience. You can restrict cookies through your browser; however that may impair site functionality.

Are you sure?

My order summary

Growing Up Poor Made Me a Stronger, More Confident Adult

I don't want to just survive. I want to live.

I never imagined the struggles that my parents faced would affect me as an adult today. My parents were underprivileged – same as their parents, and everyone in their families before them. But it was hard to accept that we were poor because it never felt that way. We had everything we needed: food, clothes, and a roof over our heads. It just wasn't enough.

As a child, my mother used to take me shopping for school clothes in the basement of an old church. I remember hiding between rounded racks of airless shirts and peeking through them every so often to make sure she was still nearby. The room was filled with anxious women who were racing to find the best bang for their hard-earned buck while scraping wire hangers against metal rods—a sound that sends chills through my spine to this day.

Most of the time, I went undetected while crouching beneath the madness, but on those rare occasions when one of the women did happen to catch my eye, we would both smile coyly and go on about our business. One of the memories I hold is of a tiny, rectangular window at the top of the ceiling in the church that looked out into the street. Whenever it stormed, the raindrops would glide down the front of the glass, like my own tears. Although I was young, I knew we deserved better than second-hand pajamas with Kool-Aid stains on them, and I swore when I got older that I would never end up like my mother.

My mother worried about the future, especially when it involved spending money. It was her belief that you were damned if you do and damned if you don't , so you may as well accept reality. She taught me early on to walk straight to the back of a store whenever we shopped because that's where they kept all the sales racks. In all my years of knowing her, she has never once paid full price for anything, and everything we were given as children had been donated, recycled or red-tagged at least three times. It was, quite simply, our normal .

Hardship was different in the 1970s. We called it "middle-class." It was an era of keeping your nose to the grindstone without ever losing hope. As children, we knew not to ask for things that our parents couldn't afford. And on birthdays and holidays, when mom handed us a Sears catalog and said we could circle whatever we wanted, it was clear that she meant within reason . One of the toughest decisions I ever had to make as a little girl was choosing something that wouldn't put more pressure on my parents than they already had.

My parents did the best that they could, but they never encouraged me to further my education, which is something I have often regretted. Most likely, they were afraid of the costs involved and unaware of financial aid and scholarship opportunities because neither one of them went to college. They did the only thing they knew how: survived. Though I don't blame them for my poor judgment, I do believe that things may have turned out differently for me had I focused on applying to a university instead of to a job as a receptionist. Perhaps a degree would have given me the confidence I was lacking to pursue a dream that took an extra 20 years to achieve without one.

"In the past eight years, we've lost everything, but like my mother, I have never given up hope."

The poverty train goes on until you jump off of it. My mother is in her mid-70s now and is still working to keep a roof over her head. She has a nice home and everything she needs, but just as it was 40 years ago, it isn't enough. Still, she never backs down.

When my husband lost a lucrative job in 2007, I never imagined that I would end up in the same place I was as a child: living on false expectations in a tiny house that we couldn't afford to maintain. In the past eight years, we've lost everything, but like my mother, I have never given up hope.

More than hope, confidence comes into play. For a long time, I lacked the confidence to overcome my insecurities, which has kept me frozen in an ice block of redundancy—until now.

Hope and confidence are similar, but only one of them permits you to excel in the face of fear. This past year, for example, I have tried to live up to my potential as much as I can.

I no longer hope that my efforts will pay off because in many ways they have already. As for our daughter, she will go to college. I have made it my mission to ensure that she is financially independent and confident in her ability to succeed in life, even if it means I have to suffer during mine to see it through. If I play my cards right, she will learn from my mistakes and never know what it is like to live paycheck-to-paycheck.

In our household, can't is a word my daughter knows never to use.

Work + Money

So Many Amazon Leggings Are on Sale Right Now

The Best Deals From Walmart's Labor Day 2024 Sale

30 Work from Home Jobs That Bring in the Cash

Genius Back-to-School Money Saving Hacks

42 Best Medical School Graduation Gifts

30 Best Gifts for Lawyers & 2024 Law School Grads

What to Know About Amazon's Big Spring Sale 2024

Shop the Best Lowe's 2024 Presidents' Day Sales

The AirPods Pro Are Just $189 Right Now

The Best Presidents’ Day Mattress Sales 2024

The Best Amazon Presidents' Day Sales of 2024

32 Best Wayfair's Presidents’ Day Deals of 2024

- Login / Sign Up

With 25 days left, we need your help

The US presidential campaign is in its final weeks and we’re dedicated to helping you understand the stakes. In this election cycle, it’s more important than ever to provide context beyond the headlines. But in-depth reporting is costly, so to continue this vital work, we have an ambitious goal to add 5,000 new members.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

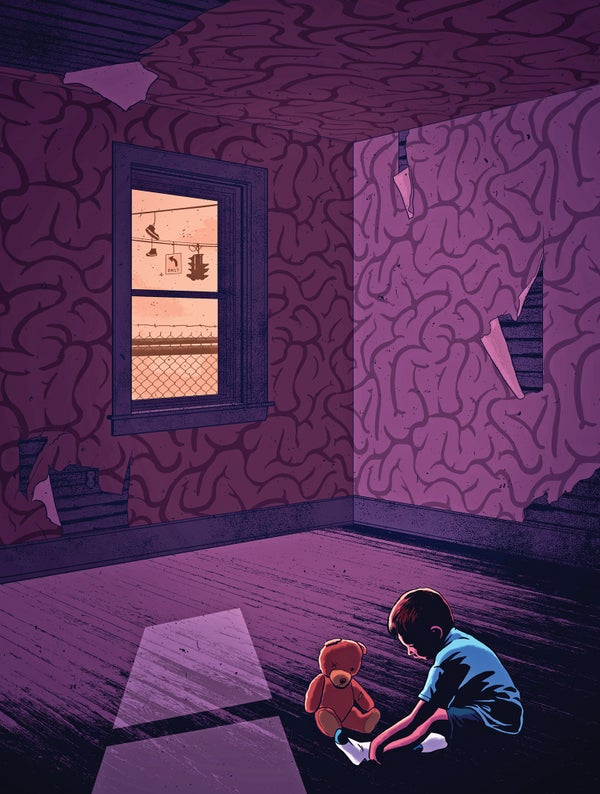

The hardest part about growing up poor was knowing I couldn’t mess up. Not even once.

by David Tran

I think we have an ideology about talent that says that talent is a tangible, resilient, hardened, shiny thing. It will always rise to the top. To find and encourage talent, all you have to do as a society is to make sure the right doors are open. Free campus visits, free tuition, letters to the kids with high scores. … You raise your hand and say, “Over here!” And the talent will come running, but that’s not true … [i]t’s not resilient and shiny … [t]alent is really, really fragile.

— Malcolm Gladwell

I grew up in East Oakland, California, as the youngest son of Teochew-Vietnamese immigrants. School was always easy for me — I never really felt challenged throughout elementary school. Amid the droves of teacher strikes and substitutes, the truly dedicated teachers of Oakland’s Maxwell Park Elementary School were few and far between.

But in fifth grade, I was fortunate enough to be taught by Mrs. Harris, who changed my life forever. On weekends, Mrs. Harris invited students to her house for lunch. Using her own money, she gave away trinkets to those who did well on assignments.

And during a parent-teacher conference, she did something unthinkable and so incredible that I didn’t fully comprehend its impact until years later. She begged my parents to have me apply to private middle schools to get me out of the failing Oakland public schools .

My parents, who don’t speak much English, did not understand what was happening. They didn’t know what a private school was, let alone why anyone would pay for school when there was free public education. Neither graduated from high school before fleeing from Vietnam to America with my eldest brother in tow. While they valued education for their children, they thought of education as uniform and binary — you either went to school or you didn’t. And as long as their kids went to school, that was good enough.

I had taken a shot at the big leagues, trying to get into a better school, and I had been rejected. I wasn’t smart enough. I hadn’t worked hard enough. I wasn’t enough.

If it had been up to my parents, nothing would have happened. But Mrs. Harris was hell-bent on making sure that I would have this opportunity for a better education. Every day, she would ask me, “So have you started applying yet?” “Did your parents look into Head-Royce yet?”

After weeks of hounding my parents, Mrs. Harris, my brother, and most of my 16 aunts and uncles managed to convince my parents to look into this private school idea. Thanks to their efforts, I ended up applying to the prestigious Head-Royce School in Oakland, taking the admissions test, and getting accepted.

But I didn’t attend. Instead, I ended up going to the local public middle school because my parents and I had failed to turn in the financial aid forms before the deadline . It took a village to push my parents to apply to Head-Royce, but there wasn’t anyone around to help us with something as mundane yet essential as filling out the financial aid forms on time. There probably were people who could have helped us, but my parents didn’t want to bother anyone by asking for help. That was their immigrant mindset: You shut up, work hard, and definitely don’t burden others.

I got a voicemail from the head of admissions at Head-Royce, asking if I still wanted to enroll despite the lack of financial aid. Growing up, I never really thought that we were poor, or at least I didn’t understand what that meant. The words “federally assisted lunch program” actually made me feel special since I got free lunches at school.

But once I found out that the school’s tuition cost more than my parents made in a year, I realized there was a world beyond what I had known. Before applying, I had no idea that Head-Royce or private schools even existed, but now that I had a window into that world, it felt like the window had been boarded over, shutting me out.

Here’s the crazy part — I internalized this whole process to mean that I wasn’t good enough for Head-Royce. I had taken a shot at the big leagues, trying to get into a better school, and I had been rejected. I wasn’t smart enough. I hadn’t worked hard enough. I wasn’t enough.

At first, my parents complained about the unfair system. However, soon after, both my parents and I took the closed door to mean that I wasn’t good enough, that I hadn’t scored high enough on the tests, that Head-Royce didn’t want me after all. If I had and if they did, they would have given me a scholarship. I felt awful and ashamed. I wasn’t good enough.

It’s a feeling that has persisted throughout my life, even as I attended an excellent college and started a successful company. It’s a feeling that many people like me — people who have fought their way out of poverty — struggle with. This is a problem we need to fix, and fast.

I really needed someone to believe in me

I might have given up on myself, but Mrs. Harris refused to give up on me. When she found out that I wasn’t going to Head-Royce, she went to work on a backup plan. We tried to get into a better public middle school in the wealthy part of Oakland, but nothing came of our efforts. Undeterred, Mrs. Harris contacted and pushed to get me into the Heads Up summer program, which offered free classes at Head-Royce for underserved kids.

During summer classes at Heads Up, I felt challenged academically for the first time ever and really started to love school. That newfound appreciation for education also rubbed off on my parents — they somehow saved up enough from their minimum wage jobs to pay for a math tutor whose house I went to twice a week that year. Mrs. Harris changed everything. I hope she’s reading this, since I don’t think I ever even said thank you. Thank you.

Given the long odds we beat to get here, sometimes in our heads, our world feels very fragile; at any moment, the clock could strike midnight

Those summer classes gave me hope during sixth grade, which ended up feeling like a lost year. I can’t remember any of the teachers’ names. I just have memories of the English teacher who the kids made cry and the substitute math teacher who yelled at me when I corrected him on how to do long division — never mind why a sixth-grade class was still being taught long division.

I applied again to Head-Royce, this time for seventh grade. We applied for financial aid as soon as it opened up and had several people check over the forms to make sure everything looked right. Thanks to the generosity of the Malone Family Foundation , I received a financial aid package that allowed me to attend the school.

Head-Royce felt like paradise. Everyone there was smart and loved to learn. The coursework was actually challenging. I loved it. Even so, I never felt like I fit in. I never, ever told anyone about what had happened when I had previously applied to Head-Royce — it remained a huge, shameful, dirty secret. I don’t think I ever got over that feeling that I wasn’t good enough, though it certainly motivated to me to work my butt off.

Years later, at Stanford, where a large percentage of the student body receives some financial aid, I maintained that internalized feeling of not belonging in this world, of not being good enough. I never talked about it. Not at Head-Royce. Not at Stanford.

Why the feeling of not being good enough haunts kids who grew up poor

On my way to a friend’s new luxury apartment in San Francisco last month, I listened to an episode of Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History podcast called “Carlos Doesn’t Remember.” I quickly found myself in tears — the protagonist’s story was my story. It was probably many of your stories.

Carlos is a smart, hard-working high school sophomore from a bad part of LA. He was fortunate enough to meet Eric Eisner, a former entertainment lawyer who founded a program called YES to help kids like Carlos get a scholarship to an elite private school. It sounds like he’s got his ticket out, but it’s never that simple. You don’t just leave behind where you came from because you get a scholarship to a good school.

Gladwell revisits a moment in Carlos’s life when his private school teachers were concerned that he didn’t play with the other kids during recess. It wasn’t due to a lack of friends, because he was usually very gregarious in the classroom. Nor was it due to him feeling self-conscious as the only Hispanic kid at the predominantly white school. Eisner found out: He literally couldn’t play because his shoes were three sizes too big and he couldn’t afford another pair .

Carlos had also been accepted to a prestigious boarding school but didn’t enroll because he didn’t want to leave his sister alone in foster care. He doesn’t like to talk about these things — in fact, he claims he doesn’t remember any of these incidents.

Carlos’s story highlights a problem that I’ve experienced but was never able to articulate. While scholarships are supposed to be an equalizer — and we as a society should continue to make education more affordable and scholarships available — the real battle underprivileged kids face can be much more insidious and intangible. My co-founder Ricky Yean touched on this battle in “Why it’s so hard to succeed in Silicon Valley when you grew up poor” :

Tangible inequalities — that which can be seen and measured, like money or access — get the majority of the attention, and deservedly so. But inequalities that live in your mind can keep the deck stacked against you long after you’ve made it out of the one-room apartment you shared with your dad. This is insidious, difficult-to-discuss, and takes a long essay to explain.

Being poor, you cannot afford to fuck up the opportunity that comes along

After listening to Gladwell’s podcast, I realized that both Ricky and I — any many others who’ve tried to escape poverty — are motivated by survival instinct. Once you see a way out, you become laser-focused on that opportunity. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a scholastic or sports scholarship, or a less traditional path. Being poor, you cannot afford to fuck up the opportunity that comes along.

You don’t take it for granted because you understand you’re playing by someone else’s rules. Even today, Ricky and I often feel like that. Given the long odds we beat to get here, sometimes in our heads, our world feels very fragile; at any moment, the clock could strike midnight. We’ve encouraged each other to talk more openly about these feelings, in an effort to strengthen and reinforce the reality of what we’ve built.

As Gladwell points out, it’s often only possible for poor kids like me to reach their potential when we have a champion who can not only show us the way but help carry us there. Mrs. Harris was that hero for me. She wasn’t a big-shot lawyer in this case; she was just a teacher who believed in me. She made opportunities happen for me, and she persisted when things hit unexpected roadblocks.

But not every kid is lucky enough to have a Mrs. Harris. Or an Eric Eisner. Remembering that and thinking about how many underprivileged kids must be experiencing this on a daily basis is why Carlos’s story brought me to tears.

We as a society need to do more to not only find these lost diamonds in the rough but dig them up, champion their cause, and push open doors for them — like Mrs. Harris did for me.

We always need more Mrs. Harrises and Eric Eisners, but this isn’t just a call for champions. I believe that in order to level the playing field for underprivileged, minority, or other disadvantaged groups, providing opportunities is not enough — we need to start talking openly about the differences in background, mindset, and opportunities that persist even after you attempt to level the field.

In the face of adversity, you have far fewer chances, a much smaller margin for error

When discussing diversity, people often bring up the idea of a pipeline, where the focus is on bringing in as many qualified, underrepresented, or underprivileged candidates as possible. But perhaps we should start thinking about it as less of a pipeline and more of a leaky funnel.

The fact is when you grow up poor or disadvantaged, there are innumerable places where you might drop off before you have a chance at a better life. As Gladwell points out, many of the brightest students in Carlos’s hometown end up gang-affiliated as early as the eighth grade, long before free SAT prep courses, scholarships, and admissions officers can open up doors for them. We have to do more to ensure that the underserved know what opportunities are available to them and help them through every step of realizing those opportunities.

In the face of adversity, you have far fewer chances, a much smaller margin for error. The oversights and slights you internalize over the course of many, many years make the rare opportunities you find even rarer and leave you unable to capitalize on what’s left. If we want to start to spot and seal the cracks and leaks that leave people behind, we need to begin the dialogue on unseen inequalities and unexpected drop-offs.

To everyone who has experienced this— who has felt like they don’t belong or aren’t good enough — the world needs to hear your story. Only then can it begin to give current and future underdogs a better chance at a better life. And just remember: You are good enough. You do belong.

David Tran is the co-founder and CTO of PRX.co , a venture-backed, software-powered PR startup. Previously he started Crowdbooster, a social media optimization solution, was an entrepreneur in residence at Stanford’s StartX, and graduated from Stanford with a BS in computer science. David spends a lot of his free time training for marathons and rooting for the Warriors, the A’s, and the Stanford Cardinal.

This essay is adapted from a post that originally ran on Medium .

First Person is Vox’s home for compelling, provocative narrative essays. Do you have a story to share? Read our submission guidelines , and pitch us at [email protected] .

We know how to end poverty. So why don’t we?

Most popular.

- The resurgence of the r-word Member Exclusive

- The one horrifying story from the new Menendez brothers doc that explains their whole case Member Exclusive

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- AI companies are trying to build god. Shouldn’t they get our permission first?

- How “Divorce him!” became the internet’s de facto relationship advice

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in archives

Given the Court’s Republican supermajority, this case is unlikely to end well for trans people.

Learn about saving, spending, investing, and more in a monthly personal finance advice column written by Nicole Dieker.

The latest news, analysis, and explainers coming out of the GOP Iowa caucuses.

The economy’s stacked against us.

A Texas judge issued a national ruling against medication abortion. Here’s what you need to know.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Penslar, Feldman examine plight of Jewish Americans after 10/7 attack

Can a 50-year-old philosophy help make democracy better today?

U.S. seems impossibly riven. What if we could start from scratch?

Robert Sampson, Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, is one of the researchers studying the link between poverty and social mobility.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Unpacking the power of poverty

Peter Reuell

Harvard Staff Writer

Study picks out key indicators like lead exposure, violence, and incarceration that impact children’s later success

Social scientists have long understood that a child’s environment — in particular growing up in poverty — can have long-lasting effects on their success later in life. What’s less well understood is exactly how.

A new Harvard study is beginning to pry open that black box.

Conducted by Robert Sampson, the Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, and Robert Manduca, a doctoral student in sociology and social policy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the study points to a handful of key indicators, including exposure to high levels of lead, violence, and incarceration as key predictors of children’s later success. The study is described in an April paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“What this paper is trying to do, in a sense, is move beyond the traditional neighborhood indicators people use, like poverty,” Sampson said. “For decades, people have shown poverty to be important … but it doesn’t necessarily tell us what the mechanisms are, and how growing up in poor neighborhoods affects children’s outcomes.”

To explore potential pathways, Manduca and Sampson turned to the income tax records of parents and approximately 230,000 children who lived in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, compiled by Harvard’s Opportunity Atlas project. They integrated these records with survey data collected by the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, measures of violence and incarceration, census indicators, and blood-lead levels for the city’s neighborhoods in the 1990s.

They found that the greater the extent to which poor black male children were exposed to harsh environments, the higher their chances of being incarcerated in adulthood and the lower their adult incomes, measured in their 30s. A similar income pattern also emerged for whites.

Among both black and white girls, the data showed that increased exposure to harsh environments predicted higher rates of teen pregnancy.

Despite the similarity of results along racial lines, Chicago’s segregation means that far more black children were exposed to harsh environments — in terms of toxicity, violence, and incarceration — harmful to their mental and physical health.

“The least-exposed majority-black neighborhoods still had levels of harshness and toxicity greater than the most-exposed majority-white neighborhoods, which plausibly accounts for a substantial portion of the racial disparities in outcomes,” Manduca said.

“It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.” Robert Sampson

“What this paper shows … is the independent predictive power of harsh environments on top of standard variables,” Sampson said. “It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.”

More like this

Cities’ wealth gap is growing, too

Racial and economic disparities intertwined, study finds

The study isn’t solely focused on the mechanisms of how poverty impacts children; it also challenges traditional notions of what remedies might be available.

“This has [various] policy implications,” Sampson said. “Because when you talk about the effects of poverty, that leads to a particular kind of thinking, which has to do with blocked opportunities and the lack of resources in a neighborhood.

“That doesn’t mean resources are unimportant,” he continued, “but what this study suggests is that environmental policy and criminal justice reform can be thought of as social mobility policy. I think that’s provocative, because that’s different than saying it’s just about poverty itself and childhood education and human capital investment, which has traditionally been the conversation.”

The study did suggest that some factors — like community cohesion, social ties, and friendship networks — could act as bulwarks against harsh environments. Many researchers, including Sampson himself, have shown that community cohesion and local organizations can help reduce violence. But Sampson said their ability to do so is limited.

“One of the positive ways to interpret this is that violence is falling in society,” he said. “Research has shown that community organizations are responsible for a good chunk of the drop. But when it comes to what’s affecting the kids themselves, it’s the homicide that happens on the corner, it’s the lead in their environment, it’s the incarceration of their parents that’s having the more proximate, direct influence.”

Going forward, Sampson said he hopes the study will spur similar research in other cities and expand to include other environmental contamination, including so-called brownfield sites.

Ultimately, Sampson said he hopes the study can reveal the myriad ways in which poverty shapes not only the resources that are available for children, but the very world in which they find themselves growing up.

“Poverty is sort of a catchall term,” he said. “The idea here is to peel things back and ask, What does it mean to grow up in a poor white neighborhood? What does it mean to grow up in a poor black neighborhood? What do kids actually experience?

“What it means for a black child on the south side of Chicago is much higher rates of exposure to violence and lead and incarceration, and this has intergenerational consequences,” he continued. “This is particularly important because it provides a way to think about potentially intervening in the intergenerational reproduction of inequality. We don’t typically think about criminal justice reform or environmental policy as social mobility policy. But maybe we should.”

This research was supported with funding from the Project on Race, Class & Cumulative Adversity at Harvard University, the Ford Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation.

Share this article

You might like.

Scholars trace history of group in U.S., discuss why many wrestling with what it means for Israel, their own place in nation’s culture

New book based on ideas of renowned Harvard scholar John Rawls argues it all comes down to fairness

Key would be focusing on social, political, economic fairness, according to new book on ideas of political philosopher John Rawls

Drug-free nasal spray blocks, neutralizes viruses, bacteria

In preclinical studies, spray offered nearly 100% protection from respiratory infections by COVID-19, influenza, viruses, and pneumonia-causing bacteria

Falls put older adults at increased risk of Alzheimer’s

Researchers found dementia more frequently diagnosed within one year of a fall, compared to other types of injuries

A blueprint for better conversations

After months of listening and learning, open inquiry co-chairs detail working group’s recommendations

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Poverty in America — Life in Poverty: Defying the Odds

Life in Poverty: Defying The Odds

- Categories: Child Poverty Poverty in America

About this sample

Words: 438 |

Published: Jan 25, 2024

Words: 438 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Defying the odds, works cited.

- ASHBERY, JOHN. "My Philosophy Of Life". Midwest Studies In Philosophy 33.1 (2009): 1-2. Web.

- Kass, Leon. Life, Liberty, And The Defense Of Dignity. 1st ed. San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2002. Print.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 747 words

1 pages / 477 words

1 pages / 480 words

4 pages / 1886 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Poverty in America

Homelessness started to become a dilemma since the 1930s leaving millions of people without homes or jobs during The Great Depression. Homeless people face numerous challenges every day dealing with shelters and food in order to [...]

Poverty in the United States is a complex and multi-faceted issue that affects millions of Americans every day. Despite being one of the wealthiest countries in the world, the United States has a high poverty rate compared to [...]

Michael Patrick MacDonald’s memoir, All Souls, provides a poignant and raw account of growing up in South Boston during the 1970s and 1980s. The book explores themes of poverty, violence, and racism, as well as the impact of [...]

The cycle of poverty, a phenomenon that entraps families and entire communities in a state of financial destitution across generations, stands as a formidable barrier to economic and social progress. A mosaic of socio-economic [...]

A small boy tugs at his mother’s coat and exclaims, “Mom! Mom! There’s the fire truck I wanted!” as he gazes through the glass showcase to the toy store. The mother looks down at the toy and sees the price, she pulls her son [...]

At the turn of the 19th century, a Danish immigrant by the name of Jacob Riis set out to change New York City’s slums. Jacob, born in Denmark in the year 1849, emigrated to America when he was 21, carrying little money in his [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

January 1, 2017

13 min read

Does Poverty Shape the Brain?

Growing up in a poor family can leave a mark on the developing brain. Understanding how and why has important implications for educators and society

By John D. E. Gabrieli & Silvia A. Bunge

Imagine that you are a child again. In this version of your childhood, you arrive at school hungry, tired and anxious. Your mother was not able to pay the rent this month. The cupboards are bare. A car alarm went off late last night, and it fell to you to soothe your baby brother back to sleep. You woke up early to take the bus across town, and by the time the school bell rings, you have so much on your mind that it is difficult to concentrate.

Myriad stressors collect and compound for children who grow up in poverty. Although their stories are all different, we know that the many challenges they face can have a lasting impact. In the U.S., one in four infants and toddlers lives below the federal poverty line.

Despite our societal desire to see education as an equalizer that elevates people from difficult circumstances, social scientists have known for some time that the truth is not so simple. The income of the family you are born into has a powerful effect on educational outcomes and, in turn, future job prospects and economic security. Education researcher Sean Reardon and his colleagues at Stanford University recently completed an analysis showing that children in school districts with high levels of poverty score an average of four grade levels below peers from the most affluent districts on tests of reading and math. And kids born to a low-income family have a far worse chance of getting a college degree than children born to a high-income family, in turn constricting economic and career opportunities.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As disquieting as these inequities may be, this so-called income-achievement gap is not new. Educators and social scientists have been tracking the relation between school success and poverty for roughly half a century. Although there is now some evidence that the divide may be starting to narrow—after three decades of expansion—the pace of change is too slow to help this generation or even the next. In fact, it could take 60 to 110 years to close the gap at its current rate of change, according to a 2016 calculation by Reardon.

In the meantime, strong evidence has begun to emerge about how family income relates to the development of a child's brain. In essence, scientists are finding anatomical differences tied to poverty—and some of this variation has implications for education. Everything that is learned, after all, depends on the brain's plasticity, its ability to grow and change. The new discoveries, in turn, serve not only as an added call to action but may also fuel ideas about how to best intervene.

Building the Brain

At birth, we have a rich supply of both gray matter, which is primarily composed of cell bodies, and white matter, which encompasses the tracts of cablelike axons that transmit signals from one neuron to the next. We start out with more neural material than we strictly need. The brain is sculpted into a more efficient organ as we learn and grow, strengthening some networks, eliminating others.

From late childhood through early adulthood, a part of the brain called the neocortical gray matter steadily thins. This area comprises six layers of cortex that cover the brain and support perception, language, thought and action. Researchers believe this thinning reflects a massive pruning of cells and the connections between them. Also during this life stage, white matter develops in ways that improve the connectivity of large-scale networks across the brain.

Scientists have only recently begun to examine how socioeconomic status (SES) might influence the normal course of brain development. SES is a complex construct that is measured by combining educational attainment, income and occupation. There is substantial variation among individuals and families at every socioeconomic level, making it hard to generalize about an individual's experiences. In addition, disadvantages, where they exist, tend to co-occur or correlate with one another, so it is difficult to relate specific circumstances to particular outcomes. For example, very low SES or poverty is associated with poor health, family instability and high stress. It can also entail malnutrition, limited health care, modest language and intellectual stimulation at home, inferior schools and lowered social expectations. These conditions could all, in turn, affect neural and cognitive development.

A classic series of experiments conducted in the 1960s at the University of California, Berkeley, proved that adverse early environments harm the brain in rodents. Neuroscientist Marian Diamond showed that rearing rats in an impoverished environment—lacking toys and opportunities to socialize—hampered their brain development and ability to learn.

Click or tap to enlarge

Credit: Rob Dobi; Sources: Child Poverty in America 2015: National Analysis . Children's Defense Fund, September 13, 2016 ( children in poverty ); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services ( poverty line ); Child Poverty and Intergenerational Mobility , by Sarah Fass et al. National Center for Children in Poverty, December 2009 ( poverty at age 35 ); Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States: 45 Year Trend Report . Revised. Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Education and Penn Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy, 2015 ( college completion for bottom quartile ); “Is College Worth It? Clearly, New Data Say,” by David Loenhardt, in the Upshot, New York Times . Published online May 27, 2014 ( pay increase with college degree )

Such studies would be unethical in humans, but a long-term follow-up of Romanian children who had been warehoused in an appalling system of state orphanages found similar outcomes. Beginning in 2001, developmental psychologists Charles A. Nelson III of Harvard University, Nathan A. Fox of the University of Maryland and Charles H. Zeanah, Jr., of Tulane University compared kids who remained trapped in that system with those who escaped to foster care or adoption and found dire emotional and cognitive repercussions for the first group. They confirmed that the environment can shape cognitive and brain growth and showed that a supportive intervention can substantially ameliorate early privations.

Seeing the Difference

Most children growing up in poverty face some adversity, but it is rarely as extreme as the absence of human interaction and enrichment experienced by the Romanian orphans. Nevertheless, even lesser deprivation appears to alter brain development. In the past few years several large, high-quality studies using MRI have linked variation in a child's neuroanatomy with family income. In no area are the disparities more striking than in the cortex.

One of us (Gabrieli) has made this observation in his own laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He, Allyson Mackey and their colleagues compared cortical thickness among 58 eighth grade students from lower-income versus higher-income families. The results, published in 2015, revealed that the lower-income group had a thinner cortex in widespread regions of the brain. For all students, regardless of income, a thicker cortex was associated with better scores on statewide tests of reading and math. This study, therefore, directly related family income, brain anatomy and educational achievement.

In the same year, cognitive neuroscientist Kim Noble of Columbia University and her colleagues published findings from an MRI examination of 1,099 children ages three through 20. They discovered that cortical surface area was larger in children with greater family income. Critically, they found that small differences in income among families earning less than $50,000 a year were associated with relatively large differences in surface area. But this pattern did not hold true among kids from families who made more than $50,000. These findings suggest a threshold model in which small disparities in earnings may matter greatly among lower-income individuals, but above a certain income level, these differences have less impact.

Also in 2015 Seth Pollak, a psychologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, published a study of 389 children and young adults, aged four to 22, that examined the relation between household poverty, academic performance and MRI data. He and his colleagues found that people with higher scores on cognitive and achievement tests had greater cortical volumes in the frontal and temporal lobes—and, as in the other studies, poorer children had less cortical gray matter (a finding that in all three studies was unrelated to race or ethnicity).

All of this work is correlational, so it is important to note that it cannot prove whether or not an impoverished environment caused these changes—or, for that matter, whether these differences in structure definitely translate into academic deficits. There are some remarkable students, for example, who do very well in school despite an impoverished background, and we do not know how their neural structure compares. It may resemble that of a more affluent child—or perhaps their brain can compensate, enabling equal academic performance despite differences in brain architecture.

The consistent finding that poverty is associated with a smaller cortex is notable, however, because we associate brain maturation from childhood through young adulthood with a thinning cortex. In fact, several studies have reported that better cognitive abilities are associated with a thinner cortex among adolescents at a given age. (These findings most likely involved children from higher-income families who are more likely to volunteer for research studies.)

Total Gray Matter: Using MRI to track brain development in 77 infants, psychologists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison found that differences associated with socioeconomic status (SES) became increasingly pronounced over time. By age three, toddlers from low-income households showed significantly less gray matter than those raised in wealthier homes. Source: “Family Poverty Affects the Rate of Human Infant Brain Growth,” by Jamie L. Hanson et al., in PLOS One , Vol. 8, No. 12, Article No. e80954; December 11, 2013

On the one hand, a reduced cortex may simply reflect the deleterious consequence of impoverished environments. On the other hand, it could reflect a protective adaptation to such environments. Accelerated thinning could perhaps diminish the influence of negative experiences on the developing brain. Preventing the brain from being shaped by harsh influences over the course of many years could be an evolutionarily adaptive response, helping a child to better cope in adverse conditions—but premature thinning could also reduce education's influence on the developing brain.

A Question of Timing?

Researchers have been trying to determine when brain differences associated with SES first become apparent: Do they start in the womb or as an infant experiences more or less supportive environments after birth? In principle, brain imaging offers a novel way to answer these questions, but findings thus far have been inconsistent.

One 2015 study of 44 infants by cognitive neuroscientist Martha Farah of the University of Pennsylvania and her colleagues found that by one month of age, higher SES (defined by income and maternal education) was associated with larger cortical volume in girls. This finding suggests that differences emerge very early—although it is hard to know what such variation means.

Pollak and his colleagues, however, looked at infants aged five months to four years and in 2013 found that SES-related brain differences were minimal at early ages but increased over time. This gap does not grow indefinitely, however. Investigation later in life has yielded no evidence for widening brain differences after early childhood.

It is also important to consider the specific influences that may shape development during these years. Another study by Farah linked home environment to brain development. Researchers visited homes when children were four and then again at eight years of age, and both times they measured environmental stimulation, such as exposure to books, conversation, trips and music.

When the same group of kids reached adolescence, they were given MRI scans. The researchers found that a stimulating home at age four, but not at age eight, predicted greater cortical thickness in the frontal and temporal cortex. It may be that the home environment has a particularly powerful influence on brain development in the early childhood years—or that by age eight, school and social peers exert greater influence than the home does.

It is also possible that, given the range of factors related to socioeconomic status, there may not be a single or simple answer to the question of when brain differences first emerge. Furthermore, there may not be a special or “critical” period of development that is uniquely potent in predicting long-term outcomes. It seems logical that early preventive help is more likely to be effective than remedial support after a child has fallen behind, but education occurs continuously through a child's development and matters at all ages.

Finding Ways to Help

Early experience does not determine outcomes; it merely influences their probability. Given individual variation in response to adversity, we cannot and should not make assumptions about a child's potential based on his or her background. The brain, after all, is plastic and continues to change with experience over a life span.

Yet the longer we wait to get started, the more intensive the effort we may need to counteract the effects of early adversity. The detriments associated with the Romanian orphanages, for example, were not as pronounced among kids placed into family foster care early in childhood. The best solution is therefore prevention, and the next best is remediation. That means that tackling income inequality—and particularly extreme child poverty—at the societal level is of paramount importance, and we hope that neuroscientific evidence can be a spur for shifting policy in that direction. Meanwhile there are some promising steps, inspired by the new findings, that we can take to mitigate the negative effects of indigence on children.

A number of research-based programs for disadvantaged kids are showing good results. Structured group play sessions, such as those offered at Childhaven in Seattle ( left ) or a Tools of the Mind classroom such as this one at Christina Seix Academy in Trenton, N.J. ( right ), can help boost executive functions, a crucial set of skills that includes problem solving, reasoning and planning. Credit: Courtesy of Childhaven ( left ); Courtesy of Tools of the Mind ( right )

There are a number of ways people are trying to improve life outcomes for disadvantaged children—including efforts targeting factors such as sleep and nutrition, cognitive and academic skills, and even finance, career development and parenting strategies for parents and caregivers. Columbia's Noble and her colleagues, for example, have begun a pilot project in which they are testing whether cash transfers to low-income mothers will improve their child's environment and cognition and lower maternal stress. If the threshold model is correct, even modest financial assistance could make a big difference.

Applying techniques from neuroscience may yield unique insight into a given intervention's power. One example of an approach that has been assessed in part through brain measurements is the Kids in Transition to School (KITS) program, developed by psychologist Philip Fisher and his colleagues at the Oregon Social Learning Center, which works with children in foster care and youngsters from low-income families two months before the start of kindergarten and continues until two months after entry.

Aimed at boosting self-regulatory skills, as well as early literacy and prosocial behavior, KITS includes 24 sessions of therapeutic play for children, as well as an eight-session workshop for caregivers. In the classroom, students practice skills such as sitting still and raising their hand, as well as cooperating with their peers. In the workshop, adults learn ways to establish routines with children and encourage good behavior.

Two-generation approaches are effective for many reasons, among them the fact that when parents are involved, children can be helped outside of class and they may not feel as singled out among their peers. In a paper published in 2013 Helen Neville, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Oregon, and her colleagues compared a parent-and-child intervention based on KITS with an intervention focused solely on kids. They found that the combined approach did a better job of boosting nonverbal IQ and language skills. This result was supported by electroencephalography (EEG) findings indicating that the children had a bigger improvement in their brain's capacity to filter out distracting information while focusing on a task.

Both of us are directly involved in testing other interventions for children in poverty that involve their parents and caregivers. As part of the Boston Charter Research Collaborative, Gabrieli works with teachers at six charter school management organizations, serving nearly 7,000 inner-city students in the metropolitan area. The teachers describe their challenges, and researchers at Harvard and M.I.T. offer evidence-based solutions; together they implement and evaluate these programs. Some of the participating students come for brain imaging before and after an intervention so that beneficial brain plasticity can be visualized.

Neuroimaging can also pinpoint cognitive targets for an intervention. The executive functions, for example, are a suite of skills that help people focus on a task, regulate feelings and behaviors, and consider possible consequences before making a decision. They not only increase the odds of staying in school but also appear to be highly vulnerable to poverty. Indeed, executive functions are associated with the prefrontal cortex, an area that shows clear differences in imaging studies that compare children of wealth with those of poverty.

Bunge is involved in the Frontiers of Innovation (FOI) network, established by the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard. This group of researchers and practitioners at multiple sites around the U.S. identifies and develops promising approaches for assisting parents and other caregivers of young children living in adversity. Through FOI, Bunge's team at U.C. Berkeley has been collaborating with Seattle-based Childhaven, which provides therapeutic services to children under age six who have suffered neglect or maltreatment at home. Pilot data from this work suggest that simple classroom activities, such as structured group play that requires children to follow explicit rules and take turns with their classmates, can begin to boost executive functions within 10 weeks.

Several other approaches have shown success in strengthening these functions. One example is the Tools of the Mind curriculum, an alternative to traditional kindergarten developed at Metropolitan State University of Denver by psychologists Elena Bodrova and Debora Leong. The curriculum focuses on building executive functions through “scaffolded” play, which involves targeted interactions with peers and teachers. In 2014 psychologists Clancy Blair and Cybele Raver of New York University found this program was especially beneficial in high-poverty preschools.

What Comes Next?

Although the nature of brain differences was unknown until the past decade, it had to be expected that the profound disparities in educational, occupational and health outcomes associated with childhood poverty or affluence would be reflected in the brain's development. In many ways, the findings complement the long-standing research into the income-achievement gap.

Yet this work also hints at a special role for neuroscience, beyond descriptive imaging. Monitoring the progress of a particular approach with EEG, as well as behavioral measures, for instance, can offer a fast and revealing indicator of its strengths or failings. Furthermore, the nature of neural differences associated with SES is instructive. If longitudinal evidence supports the idea that more rapid cortical thinning occurs in children raised in poverty, then developing strategies to slow such thinning could be helpful.

Ultimately individual children will respond in varied ways to any given intervention. The challenge is to develop personalized solutions that are not overly expensive or time-consuming for educators. Broadly speaking, the most beneficial programs will be intensive (involving multiple, regular sessions or spanning several years), engage a range of skills in diverse ways, and incorporate not only children and educators but also caregivers and the home environment. Best of all would be public policies and societal changes that take aim at child poverty and income inequality.

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds face many challenges, but thanks in part to the remarkable power of neuroplasticity, no one's story is predetermined. Our hope is that the new brain-based findings may inspire and guide solutions to help these kids flourish and thrive.

John D. E. Gabrieli is a professor in the department of brain and cognitive sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is director of the Athinoula A. Martinos Imaging Center at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the Gabrieli Laboratory, both at M.I.T.

Silvia A. Bunge is a professor in the department of psychology and at the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, where she also directs the Building Blocks of Cognition Laboratory.

Growing Up Poor in America

September 8 and December 8, 2020 / 54m

Season 2020: Episode 3

Their families were already struggling to make ends meet. Then came the coronavirus.

Director Jezza Neumann, who made 2012’s Poor Kids , once again delves into how poverty impacts children. With the 2020 election approaching, Growing Up Poor in America follows three children and their families in the battleground state of Ohio as the COVID-19 pandemic amplifies their struggle to stay afloat. As the country also reckons with issues of race and racism, the children share their worries and hopes about their futures.

Filmmaker Jezza Neumann on “Growing Up Poor in America”

“i don’t want to live like this forever”: a 14-year-old’s story of “hidden homelessness” amid the coronavirus pandemic, how covid has impacted poverty in america, featured documentaries, video list slider.

The U.S. COVID Death Toll Has Passed 1 Million. These Documentaries Offer Context.

What Happened to Poverty in America in 2021

As the U.S. Crosses 500,000 Deaths from COVID-19, These 9 Documentaries Offer Context

Taking Office in a Time of Crisis: 16 Documentaries on Key Issues Biden Inherits

Watch 2020’s 10 Most-Streamed FRONTLINE Documentaries

Awaiting Election Results, the U.S. Set a New Daily COVID Record. These 8 Films Offer Context.

Children in Poverty: By the Numbers

Our New Season Begins Tonight With “Growing Up Poor in America”

Next on Frontline

A year of war: israelis and palestinians, get our newsletter, follow frontline, frontline newsletter, we answer to no one but you.

You'll receive access to exclusive information and early alerts about our documentaries and investigations.

I'm already subscribed

The FRONTLINE Dispatch

Don't miss an episode. sign-up for the frontline dispatch newsletter., sign-up for the unresolved newsletter..

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Then: A childhood of poverty. My childhood was difficult, because my parents separated when I was just 2. My father went to Barranquilla, Colombia, leaving my mother very sick. Our economic situation wasn’t the best.

Growing Up Poor Made Me a Stronger, More Confident Adult. I don't want to just survive. I want to live. By Lisa René LeClair Published: Jan 15, 2016. I never imagined the struggles that my...

The fact is when you grow up poor or disadvantaged, there are innumerable places where you might drop off before you have a chance at a better life.

Social scientists have long understood that a child’s environment — in particular growing up in poverty — can have long-lasting effects on their success later in life. What’s less well understood is exactly how. A new Harvard study is beginning to pry open that black box.

Words: 439 | Page: 1 | 3 min read. Published: Apr 29, 2022. According to Google, although some researchers argue differently, the main effects of growing up in poverty include poor health, a high risk of teen pregnancy, and the lack of an education.

My life as a fourth-born in a poor family was not one anyone would wish to experience, especially at a young age. My parents, who were never able to attend elementary school, struggled to take care of the family.

Growing up in a poor family can leave a mark on the developing brain. Understanding how and why has important implications for educators and society

Growing up poor can carry long-term health implications. Poverty itself can be dangerous. Children growing up poor are more likely to be injured in accidents, and five times more likely to...

The economic crisis that we find ourselves in today threatens to cause a dramatic increase in the number of America’s poor children; however poverty in America has long been a crisis that has faced the children of our nation. This essay will investigate the previous asked questions and research

When it comes to tracking how poverty impacts American families with children — a subject documented in 2017's 'Poor Kids' and 2020's 'Growing Up Poor in America' — estimates for 2021...