Psychology Discussion

Essay on human behaviour: top 5 essays | psychology.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Here is an essay on ‘Human Behaviour’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Human Behaviour’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Human Behaviour

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Controversies in the Study of Human Behaviour

1. Essay on the Introduction to Human Behaviour:

After all, Homo sapiens has a science all its own, namely anthropology, and the other “social sciences” are almost exclusively concerned with this one species too. Nevertheless, many animal behaviour researchers, undaunted by all these specialists, have made Homo sapiens one of their study species, a choice justified by the fact that theories and methods developed by students of nonhuman animals can often illuminate human affairs in ways that escape scientists whose training and focus is exclusively anthropocentric.

The continuity of anatomy, physiology, brain, and human behaviour between people and other animals clearly implies that nonhuman research can shed light on human nature. Medical researchers rely on this continuity, using “animal models” whenever human research would be premature, too intrusive, or too risky. The same is true in basic behavioural research.

Consider, for example, the study of hormonal influences on human behaviour. The “activating” effects of circulating steroid hormones on sexual motivation aggression, persistence, and other behavioural phenomena were first established in other species and only then investigated in human beings.

Similarly, non-human research on the “organizing” (developmental) effects of these same gonadal hormones has motivated and guided human research on the behavioural consequences of endocrine disorders. In a more recent example, discoveries concerning the role of androgens in mediating tradeoffs between mating effort and male parental effort in animals with biparental care have inspired studies of the same phenomena in human fathers.

The situation is similar, but much more richly developed, in behavioural neuroscience, where virtually everything now known about the human brain was discovered with crucial inspiration and support from experimental research on homologous structures and processes that serve similar perceptual and cognitive functions in other species.

The fact that Homo sapiens is a member of the animal kingdom also means that it is both possible and enlightening to include our species in comparative analysis. A famous example is the association between testis size and mating systems. If a female mates polyandrously, i.e., with more than one male, and if she does so within a sufficiently short interval, then the different males ejaculates must “compete” for the paternity of her offspring.

Thus, although human testes are smaller than those of the most promiscuous primates, they are nevertheless larger than would be expected under monogamy; this observation has substantially bolstered the notion that ancestral women were not strictly monogamous in their sexual behaviour and hence that selection may have equipped the human female with facultative inclinations to cuckold their primary partners by clandestine adultery, or maintain multiple simultaneous sexual relationships, or both.

These ideas, which run contrary to the previous notion that only males would be expected to possess adaptive tendencies to mate polygamously, have had substantial impact on recent research into women’s sexuality.

2. Essay on the Research of Human Behaviour:

Getting involved in human research appears to be an occupational hazard for animal behaviour researchers. In his 1973 Nobel Prize autobiography, Niko Tinbergen revealed that he had long harbored a “dormant desire to make ethology apply its methods to human behaviour,” a desire that he acted upon, late in his research career, by studying autistic children.

Others made the move earlier in their careers, with greater impact. The British ethologist Nicholas Blurton Jones, one of the founders of “human ethology” and now a major figure in hunter-gatherer studies, did his PhD work on threat displays in the great tit (Parus major) but then began almost immediately to study human children.

He writes: “I studied at Oxford with Niko Tinbergen [who] shared the Nobel Prize with Konrad Lorenz for their demonstration that human behaviour should be studied in the same way as any other feature of an animal – as a product of evolution by natural selection.”

Just as they had done in their studies of other animals, Blurton Jones, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, and others who had begun to call their field of research human ethology initially concentrated on categorizing overt motor patterns and counting how often each behavioural act was executed.

Indeed, other scientists without animal behaviour training were coming to similar views about the need for a more objective observational approach at about this time, and a few even turned to Darwin for inspiration. An interesting example is the work of Paul Ekman, an American psychologist who traveled to highland New Guinea and other remote places to prove that facial expressions of emotion and their interpretations by observers is cross- culturally universal rather than exhibiting arbitrary cultural variation from place to place, as many anthropologists had supposed.

This research program was akin to that of Eibl- Eibesfeldt in its questions, its theoretical foundations, and its results, but perhaps because Ekman was trained in psychology, he was less reluctant than the ethologist to use elicited verbal data as his test of universality.

Of course, one might say that the classical ethological approach has withered in nonhuman research too, with the ascendancy of behavioural ecology, but the hallmark of classical ethology, namely observational study of human behaviour in its natural context, has not been forsaken.

3. Essay on the Uniqueness of Human Behaviour:

Another reason why treating human beings as “just another animal” can be problematic is that in many ways we are very exceptional animals indeed. Although other creatures can learn from conspecifics and may even have local traditions, human cultural transmission and the diversity of practices that it has engendered are unique, and how we should approach the study of human behaviour from an evolutionary adaptationist perspective is therefore controversial.

One approach to the issue of cultural diversity is to attempt to make sense of the distinct practices of people in different parts of the world as representing facultative adaptation to the diversity in local ecological circumstances.

A nice example is provided by demonstrations that cross- cultural variation in the use of spices is partly to be understood as response to variation in local and foodstuff- specific rates at which unrefrigerated foods spoil and in the antimicrobial effectiveness of particular spices.

Presumably, such cultural adaptations are usually the product of an “evolutionary” process that does not entail cumulative change in gene pools but only in socially transmitted information and practices, although there are certainly some cases in which there has been gene-culture coevolution. The best-known example of the coevolution of human genes and human culture concerns the variable prevalence of genes that permit people to digest milk and milk products beyond early childhood.

In populations that lack dairying traditions, most adults are lactose-intolerant and suffer indigestion if they drink milk, because they no longer produce lactase, the enzyme that permits us to metabolize lactose. But in populations with a long history of dairying, genotypes that engender persistent lactase production into adulthood predominate, apparently as a result of natural selection favouring those able to derive nutrition from their herds.

Enlightening as such approaches may be, however, they can never make functional sense of every particular cultural phenomenon, for it is certain that a great deal of cultural variability is functionally arbitrary in its details, and at least a few culturally prescribed practices have disastrous fitness consequences.

A famous example, of such a disastrous cultural practice is the transmission of kuru, a fatal prion- induced brain disease akin to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, among the Fore people of highland New Guinea. Like other prion-induced diseases, kuru is not easily transmitted under most circumstances, but as a result of funerary practices that included intimate handling of corpses and ritual cannibalism of parts of deceased kinsmen, the Fore suffered an epidemic resulting in high levels of mortality.

4. Essay on the Measurement of Human Behaviour

It is true that over the decades psychology has moved towards becoming a quantitative science which tries to introduce measurements with precision and accuracy comparable to measurements in exact sciences such as physics, chemistry, etc. There is no doubt that the acceptance of model of the exact sciences has contributed very much to the growth and development of scientific psychology.

It must be stated that modern psychologists have gone far ahead of other social and behavioural sciences. In fact other social sciences such as sociology and political science have tried to adopt the tools and techniques of psychology for their own research and study.

However, the particular problem of quantifying and measuring behaviour still has its own peculiarities. While we may accept the standards and norms of accuracy and prediction set by the exact sciences, nevertheless, psychologists have had and will have to develop their own approaches to measurement and quantification of behaviour because of the very nature and characteristics of human behaviour.

Some of the peculiarities of human behaviour are given below:

Firstly all types of human behaviour are not explicit or visible. Only some aspects of behaviour are capable of being measured with instruments and gadgets directly. Thus, the inner needs and motives are difficult to measure directly.

Secondly, the individuals themselves would not be willing or ready to reveal certain aspects of human behaviour such as inner conflicts, problems of adjustments etc.

Thirdly the psycho-analytic school demonstrated the importance of unconscious processes which are not open to the awareness of the behaving individuals themselves. Such aspects have to be mostly inferred or measured through indirect methods. Thus, we may broadly categories measurements in psychology into indirect and direct measures.

Early attempts at measurement in psychology were simple and direct and were concerned with those aspects of human behaviour that could be directly measured. Later, with the enthusiasm of psychologists to measure other aspects of human behaviour, indirect approaches were developed.

By and large, sensations, learning, remembering, perception and similar variables are measured through direct means whereas indirect measures are largely used in studying motivational, personality and attitudinal variables.

Most intelligence tests are direct measures of intelligence while all the projective tests are indirect measures. Direct measures have the advantage in that they are simpler or more objective and are easy to handle, whereas indirect measures, to a large extent, depend on the interpretation of the individual’s behaviour and inference based on certain guidelines.

Yet another point that may be borne in mind is that direct measures are largely independent of specific theories of behaviour or personality. In fact, psychologists with different theoretical approaches and biases employed the same direct measures.

Indirect measures are largely associated with specific theories. Thus, projective tests such as the Rorschach test and TAT rest on certain basic assumptions about human behaviour and personality. Therefore, it can be said that direct measures give us measures of behaviour as they occur, while indirect measures give us scores which are arrived at on the basis of inferences and interpretations based on particular theories. Indirect measures are based on particular rationales.

It is also possible to consider psychological measures as empirical measures and rational measures. Empirical measures are based on the occurrence of certain behavioural patterns and are statistically arrived at. They are not based on any theory. Logical measures are based on certain theories. The best instance of convergence of the two traditions is found in the construction of attitude scales.

Errors in Measurement of Human Behaviour:

It is apparent that there are many instances where behavioural measures can be contaminated by errors. The requisites of accuracy, validity and reliability were explained. Naturally, when a number of errors creep in, the characteristics are affected adversely.

Errors in psychological measures are of two types; systematic errors and random errors. Systematic errors are those which occur repeatedly and are constant. For example, if while measuring the intelligence of a person, we employ a test which is too easy, then the individual’s intelligence is overestimated. Such an error is called a systematic error.

On the other hand, even if we employ a proper test and measure the individual’s intelligence on different occasions it is possible that the measured IQ on these different occasions will not be the same. Such variations are occasional examples of random errors which result from factors such as the subject’s mood, motivation, skills of the tests, etc.

Whenever we measure human behaviour we should be aware of the presence of such errors. Systematic errors are avoided by a very careful choice and usage of the test.

Random errors are taken care of by making repeated measurements and taking the average of all these scores. Errors in measurement, therefore, result from the defects in the measuring tools, defects in the measuring conditions and also certain factors in the subject as well as the experimenter.

5. Essay on the Controversies in the Study of Human Behaviour:

There are a number of current controversies in the study of human behaviour from an evolutionary perspective, and most of them closely parallel ongoing controversies in animal behaviour more generally.

One perennial point of discussion is whether measures of reproductive success are essential for testing adaptationist hypotheses. Evolutionary anthropologists who reported that wealth and/or status is positively related to reproductive success in certain societies presented these correlations as testimony to the relevance of Darwinism for the human sciences, and this invited the rejoinder that a failure to find such a correlation in modern industrialized societies must then constitute evidence of Darwinism’s irrelevance.

Anthropologist Donald Symons then entered the fray with a forceful counterargument to the effect that measures of reproductive attainment are virtually useless for testing adaptationist hypotheses, which should instead be tested on the basis of “design” criteria.

These arguments are sometimes read as if the issue applies only to the cultural animal Homo sapiens but, as Thornhill has pointed out, the same debate can be found in the nonhuman literature, with writers like Wade and Reeve and Sherman arguing that fitness consequences provide the best test of adaptationist hypotheses, whereas Thornhill and Williams defend the opposing view.

A related point of contention concerns the characterization of the human behaviour “environment of evolutionary adaptedness” (EEA). This concept is often invoked in attempts to understand the prevalence of some unhealthy or otherwise unfit practice in the modern world, such as damaging levels of consumption of refined sugar or psychoactive drugs.

The point is simply that these substances did not exist in the selective environment that shaped the human adaptations they now exploit, and that this is why we lack defenses against their harmful effects.

Essentially the same point can be made about more benign modern novelties, such as effective contraceptive devices, telephones, and erotica- there is little reason to expect that we will use these inventions in ways that promote our fitness, since they have, in a sense, been designed to “parasitize” our adaptations, and there has not been sufficient time for natural selection to have crafted countermeasures to their effects.

The EEA concept has become controversial because several writers believe that it entails untestable assumptions about the past; presupposes that human evolution stopped in the Pleistocene; and is invoked in a pseudo-explanatory post-hoc fashion to dispose of puzzling failures of adaptation.

Yet it is surely not controversial that a world with novel chemical pollutants, televised violence, internet pornography, and exogenous opiates is very different from that in which the characteristic features of human psychophysiology evolved.

Once again, these debates about the utility of the EEA concept are read as if the issue were peculiar to the human case. But in fact, any adaptation in any species has its “environment of evolutionary adaptedness,” and the notion that some adaptations are tuned to aspects of past environments which no longer exist is as relevant to the behaviour of other animals as it is to our own.

Byers, for example, has argued that various aspects of the human behaviour of the pronghorn, a social ungulate of North American grasslands, can only be understood as adaptations to predators that are now extinct.

Similarly, Coss et al. have demonstrated that California ground squirrels from different populations, none of which presently live in sympatry with rattlesnakes, may or may not exhibit adaptive anti-predator responses to introduced snakes and that the difference reflects how many millennia have passed since the squirrel populations lost contact with the rattlesnakes.

Yet another issue of current controversy concerns the reasons why there is so much genetic diversity affecting behavioural diversity within human populations. Personality dimensions in which there are stable individual differences consistently prove to have heritabilities of around 0.5, which means that about half the variability among individuals in things like extroversion, shyness, and willingness to take risks can be attributed to differences in genotype.

The puzzle is why selection “tolerates” this variability- if selection works by weeding out suboptimal variants and thereby optimizing quantitative traits, how can all this heritable diversity persist? One possibility is that the diversity is a functionless byproduct of the fact that selection on many traits is weak relative to mutation pressure; in finite populations, not all attributes can be optimized by selection simultaneously.

Another possibility is that heritable diversity in personality represents the expression of formerly neutral, variants in evolutionary novel environments. Still another view, argued by Tooby and Cosmides, is that heritable personality diversity is indeed functionless “noise” but is nevertheless maintained by frequency-dependent selection favouring rare genotypes in a never-ending “arms race” with polymorphic rapidly evolving pathogen strains.

Finally, Wilson has defended the possibility that there is a substantial prevalence of adaptive behavioural polymorphisms maintained by selection on the behavioural phenotypes themselves.

The “evolutionarily stable” state in game-theory models of social behaviour is often a mix of different types. If most individuals are honest reciprocators, for example, this creates a niche for exploitative “cheaters” whose success is maximal when they are extremely rare and declines as they become more prevalent.

Once again, this is obviously an issue of relevance in other species as well as human beings, and it is not an easy issue to resolve. However, the right answer will influence how we should look at matters ranging from sexual selection to psychopathology. Gangestad has argued that there is an evolutionarily stable mix of women with distinct sexualities such that some are inclined to long-term monogamy and others are not.

Lalumière et al. present evidence that “psychopaths,” socially exploitative people who are lacking in empathy for others, are not suffering from pathology but are instead a discrete type of person that is maintained at low frequencies by selection. How such ideas will fare in the light of future theorizing and research is an open question.

Related Articles:

- Essay on Stress: Top 7 Essays | Human Behaviour | Psychology

- Essay on Motivation: Top 9 Essays | Human Behaviour | Psychology

- Essay on Attitude: Top 8 Essays | Human Behaviour | Psychology

- Essay on Parenting: Top 5 Essays | Human Behaviour | Psychology

Essay , Psychology , Human Behaviour , Essay on Human Behaviour

Essay on Human Behaviour

Students are often asked to write an essay on Human Behaviour in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Human Behaviour

Understanding human behavior.

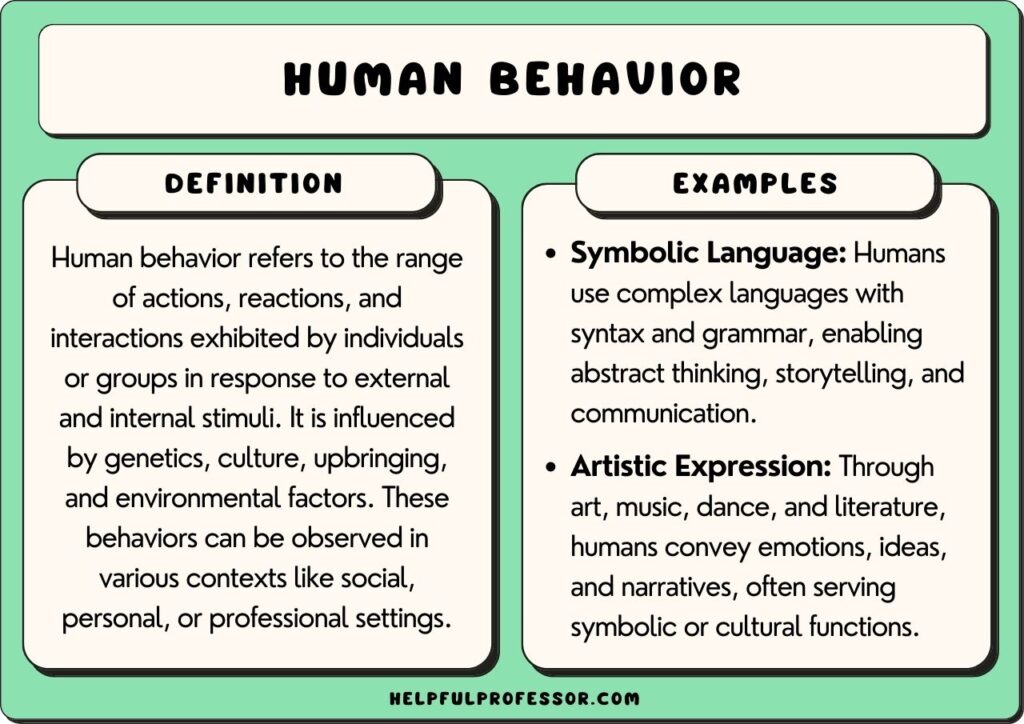

Human behavior is the way people act and react. It can be influenced by many things like feelings, the environment, or past experiences. For example, someone might be very happy at a party but sad if they lose a game.

Influences on Behavior

What we do is often shaped by where we are and who we are with. If we are with friends, we might act differently than when we are alone. Also, rules at home or school guide how we behave.

Learning from Others

We learn how to act by watching others. If a child sees a sibling sharing toys, they may learn to share too. This is called learning by example. It’s a big part of growing up.

Choices and Behavior

Every day, we make choices that show our behavior. Choosing to help someone or saying ‘thank you’ are ways we can show kindness. Our choices help shape our behavior.

Changing Behavior

People can change how they act. If someone learns that being angry doesn’t solve problems, they might try to stay calm next time. Changing behavior can be hard, but it is possible.

250 Words Essay on Human Behaviour

Human behavior is the way people act and think. It’s what we do every day, like talking, playing, and even sleeping. Scientists who study how the mind works say that many things shape our actions. These include how we grow up, the friends we have, and the rules we follow.

Why We Act Differently

Each person is unique, which means we don’t all behave the same way. Imagine you have a twin. Even if you look the same, you might like different foods or games. This is because our choices often depend on our own personal experiences and feelings.

We learn a lot by watching other people. For example, if you see someone getting a reward for being kind, you might start being kinder too. This is called learning by example. Parents, teachers, and friends can all be examples that we learn from.

Feelings and Behavior

Our feelings play a big part in how we act. If you are happy, you might smile or laugh. But if you’re sad, you might not want to play. Understanding our emotions can help us know why we act in certain ways.

Choices and Consequences

Every action has a result, which can be good or bad. If you study hard, you might get good grades. This shows that making good choices can lead to good things happening.

In conclusion, human behavior is a mix of many things, including our surroundings, learning, and feelings. By understanding why we do things, we can make better choices and understand others better too.

500 Words Essay on Human Behaviour

Human behavior is the way people act and think in different situations. It’s like a code that tells us what someone might do next. Everyone is unique, so their actions can be very different from one another. Scientists and psychologists study human behavior to learn why we do the things we do.

Why We Act the Way We Do

A big part of our behavior comes from our brains. Our thoughts and feelings can push us to act in certain ways. For example, if you feel happy, you might smile or laugh. If you are scared, you might run away or hide. Our families, friends, and even the places we live also shape our actions. They teach us what is okay to do and what is not.

From the time we are babies, we watch and copy others. This is how we learn to walk, talk, and eat. As we grow older, we keep learning by watching others. We learn good habits, like saying “please” and “thank you,” and sometimes bad habits too. This copying is a powerful way we learn behavior.

Choices and Decisions

Every day, we make choices. Some are small, like what to wear, and some are big, like whom to be friends with. When we make a choice, we think about the good and bad things that could happen. This thinking helps us decide what to do. Our choices can affect not just us, but also other people around us.

Feelings play a huge role in our actions. When we are happy, we may do kind things. When we are angry, we might do things we later wish we hadn’t. Understanding our feelings can help us control our actions better. It’s like having a remote control for our behavior.

Group Behavior

When we are in a group, we might act differently than when we are alone. This is because we want to fit in with the group. Sometimes, being part of a group can make us braver and do things we wouldn’t do by ourselves. Other times, we might do something just because everyone else is doing it, even if we know it’s wrong.

Change Over Time

As we get older, our behavior changes. A little child might throw toys when angry, but as they grow, they learn new ways to show they are upset. We all learn and change as we have more experiences. It’s like getting updates on a computer; we get better at handling different situations.

Human behavior is a big and interesting subject. It’s about why we do things, how we learn from others, and how we change over time. By understanding behavior, we can get along better with others and make good choices. It’s important for us to think about why we act the way we do, so we can be the best versions of ourselves.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Human Cloning

- Essay on Human Body System

- Essay on How To Stay Healthy

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Human Behavior: Nature or Nurture?

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe Galton’s contributions towards the Nature and Nurture theory.

- Differentiate between the influence of genes and environment, as well as a combination of both.

- Define and Describe Epigenetics.

- Explain the difference between Social Learning Theory and Genetic Inheritance Theory.

- Explain the findings of the Bobo doll experiment.

- Understand the Grizzly Bear article.

- Understand the Beyond Heritability: Twin Studies article.

- Understand key concepts and definitions pertaining to nature vs nurture.

Introduction: What Do We Mean By Nature Vs Nurture?

In this chapter it is discussed that nature vs nurture is the debate of whether we are a product of nature (genetics) or nurture (environment). There is evidence supporting both sides of the debate. By the end of this, you should be able to determine that both nature and nurture play a key role in humans and animal behaviour.

Memory Match

The memory match game allows you to identify keywords pertaining to nature and nurture. The goal is to click a card and match the word on the card, with another card that has the same word. Now that you know how to play, let’s see how many you can match!

When we refer to nature, we are talking about our genetics that we inherit from our parents. A fairly recent study (Kamran, 2016) conducted in Pakistan suggests that the parallels drawn regarding the temperament of siblings are due to their genetics. The results of this study states that the genetic makeup of relatives of the family (even deceased) also influence how the child acts. These behaviours of the child are identifiable by the family members even though the deceased family member no longer is present.

Browse through Galton’s timeline and discover his story!

Pair the Pioneer

The following pioneers play a key role in what we know about nature and nurture today! The goal of the game is to pair the correct pioneer with the correct fact pertaining to the pioneer. If you place your mouse above the pioneer, there is a fun fact that has a clue to help. Be careful, there is a trick pioneer!

- Nature: refers to all of the genes and hereditary factors that influence who we are- from our physical appearance to our personality characteristics (definition retrieved from verywellmind.com on November 17, 2019).

- Epigenetics : the study of heritable changes in gene function that do not involve changes in DNA sequence (definition retrieved from MerriamWebster.com on November 17, 2019)

When we refer to nurture, we are talking about all the environmental factors that influence us. Environmental factors include but aren’t limited to parenting style, birth order, peers, family size, culture, language, education, etc. The main argument for nurture is that the environment is what makes us who we are. Those who are on the extreme side of nurture are empiricists. They believe humans are born as blank slates and acquire all information from their environment with their 5 senses.

Behaviorism, established by John Watson, is the theory that all behavior is a result of stimulation from the environment or a consequence of the individual’s previous conditioning. Behaviorism is a school of psychology that is on the side of nurture.

A study in 2019 performed an experiment on Bonobos (a species of chimpanzee) to observe social learning. The results of the experiment found supporting evidence that Bonobos are able to learn from observing others of their species just like humans.

Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory states that people learn by observing, imitating, and modeling behavior. In 1961, Bandura’s famous Bobo doll experiment’s findings support the argument for nurture in that our environment influences our behavior.

Key Terms:

- Nurture: Environmental factors that influence our growth and behaviour.

- Empiricism: The belief that people are born as a blank slate learn everything from their environment.

Nature or Nurture? Or Both?

Given what we have discussed so far, is it genes or environment that influences behaviour? It is actually both genetic and social influences that contributes to an individual’s behaviour. Below is a video that explains how both components contribute to an individual.

Now that you understand how genes and environment work together, is it possible for one component to influence an individual more than the other? Below is an article that explains how grizzly bears’ conflict behaviour may attribute to genetic inheritance or social learning… talk about beary bad behaviour!

Beary Bad Behaviour

Grizzly bear den

Welcome to the Grizzly Bear den. Inside there are paws, click any paw to learn key concepts within the article! Don’t worry, the bears won’t bite!

A study done in Alberta, Canada analyzed the genetic and environmental relationship of grizzly bears, pertaining to their offspring’s conflict behaviour. The study predicts that aggression is determined genetically from either biological parents. If the cub’s conflict behaviour is inherited from the father’s genes, then necessary relocation of wildlife protection is necessary to avoid human-conflict interaction. If the cub’s behaviour is inherited from the mother’s genes, then relocation of female bears is much more difficult to do as there are legal wildlife implications.

The study genotyped 213 grizzly bears, most of which were males. The study described conflict-beahviour or “problem bear” as those that exemplified invasive or aggressive behaviour on private property, public property, or had an incident with an individual. The results of the study indicated that the offspring of the female parent displayed a negative interaction more so than the offspring from the male parent.

According to Morehouse et al., (2016), “ results support the social learning hypothesis, but not the genetic inheritance hypothesis as it relates to the acquisition of conflict behaviour. If human-bear conflict was an inherited behaviour, we would have expected to see a significant relationship between paternal conflict behaviour and offspring behaviour. Social learning has the potential to perpetuate grizzly bear conflicts highlighting the importance of preventing initial conflicts, but also removing problem individuals once conflicts start” (p.7).

Beyond Heritability: Twin Studies

In this study, it talks about the general observations of 50 study samples regarding over 800,000 pairs of twins and how their behavior may have been impacted by genes or by their environment. Due to the ethical limitations of human experimentation, there can only be a conclusion that there are mild causal effects. Heritable estimations are quite frankly useless in these studies because the results purely depend on the environmental conditions of the study participants, and it only becomes applicable when all participants are in the same environment.

If a separated teen is brought up in a rich environment, their gene makeup has a higher likelihood of being a factor in their upbringing. If his or her counterpart twin, in contrast, is brought up in a poor environment, the influence of their genes will be insignificant because of a less nurturing surrounding. Another example is the first sexual encounter on separated twins; do their shared genetics influence them to take action around the same time? The answer is no, because such events are a result of the environmental influences of delinquency.

Psychologist Eric Turkheimer states that there are essentially Three Laws of Behaviour Genetics:

“First Law: All human behavioural traits are heritable.

Second Law: The effect of being raised in the same family is smaller than the effect of the genes.

Third Law: A substantial portion of the variation in complex human behavioural traits is not accounted for by the effects of genes or families.”

He explains that genes only make up ~50% of our behaviours while the rest is influenced by our environment.

“The omnipresence of genetic influences does not [mean] that behaviour is less psychological or more biologically determined”, but it’s the facilitation of the environmental conditions that allows people to bring out their full behaviouristic tendencies to light; and even then, our genes are only half the story.

The following video is a study that looked at the effects of nature and nurture on twins. In short, there are many coincidences that may seem that their actions come from genetic relations.

- To answer the question of whether we are a product of Nature or Nurture, we are both. We are a product of our genetics, and our environment. Through our genetics, we have a certain baseline personality, but that changes over time due to the influence of our surroundings: the people we hang out with and the overall level of nourishment in our growing environment.

- In summary, based on several studies and research it can be concluded that human behaviour is both nature and nurture. In addition, evidence also supports that animal behaviour specifically (grizzly bears) is also due to nature and nurture. Many aspects of the nature vs. nurture theory argues that various behaviours in humans are based both on genetics and the environment of an individual. However, it is possible that one variable from the theory may contribute more of an effect on the individual.

Chapter References

ABC News (2018, Mar 10) 20/20 Mar 9 Part 2: Adopted twins were separated and then part of a secret study. Retrieved November 17, 2019, from https://youtu.be/0-2FFsuitO4

Benjamin, J. (2017, March 31). Cancer: Nature Vs. Nurture. Retrieved November 17, 2019, from https://marybird.org/blog/olol/cancer-nature-vs-nurture

Biography.com Editors. (2019, August 28). Charles Darwin Biography. Retrieved November 17, 2019, from https://www.biography.com/scientist/charles-darwin.

Cherry, K. (2019, July 1). The Age Old Debate of Nature vs. Nurture. Retrieved November 19, 2019, from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-nature-versus-nurture-2795392.

David L, “Social Learning Theory (Bandura),” in Learning Theories, February 7, 2019, https://www.learning-theories.com/social-learning-theory-bandura.html .

Det medisinke fakultet. (2016, January 26). Epigenetics: Nature vs nurture. Retrieved November 17, 2019, from https://youtu.be/k50yMwEOWGU

Everywhere Psychology. (2012, August 28). Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment. Retrieved November 19, 2019, from https://youtu.be/dmBqwWlJg8U .

FuseSchool-Global Education. (2019, August 27). Nature vs Nurture | Genetics | Biology | FuseSchool Retrieved November 18, 2019 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EmctxRcmloc

Gervais, M. (2017, August 31). Dr. Albert Bandura – The Theory of Agency. Retrieved November 19, 2019, from https://art19.com/shows/minutes-on-mastery/episodes/a1cef11d-e32c-4f03-ba4a-262a91268f4c.

Johnson W, Turkheimer E, Gottesman II, Bouchard TJ Jr. Beyond Heritability: Twin Studies in Behavioral Research. Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2010;18(4):217–220. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01639.x

Kamran, F., PhD. (2016). Are siblings different as ‘day and night’? parents’ perceptions of nature vs. nurture. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 26 (2), 95-115. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.kpu.ca:2443/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.kpu.ca:2443/docview/1864042019?accountid=35875

Merriam-Webster. (2019). Retrieved November 17, 2019 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/epigenetics

McLeod, S. A. (2016, Feb 05). Bandura – social learning theory . Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html

McLeod, S. A. (2018, Dec 20). Nature vs nurture in psychology. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/naturevsnurture.html

Miko, I. (2008) Gregor Mendel and the principles of inheritance. Nature Education 1( 1 ) :134

Morehouse, A. T., Graves, T. A., Mikle, N., & Boyce, M. S. (2016). Nature vs. nurture: Evidence for social learning of conflict behaviour in grizzly bears. PLoS One, 11 (11) doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.kpu.ca:2080/10.1371/journal.pone.0165425

Rose, H., & Rose, S. (2011). The legacies of francis galton. Lancet, the, 377 (9775), 1397-1397.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60560-6

Shorland, G., Genty, E., Guéry, J.-P., & Zuberbühler, K. (2019). Social learning of arbitrary food preferences in bonobos. Behavioural Processes, 167. https://doi-org.ezproxy.kpu.ca:2443/10.1016/j.beproc.2019.103912

TED-Ed. (2013, March 12). How Mendel’s pea plants helped us understand genetics. Retrieved November 17, 2019, from https://youtu.be/Mehz7tCxjSE.

Thesaurus.Plus . (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2019, from https://thesaurus.plus/thesaurus.

Turkheimer, E. (2000). Three laws of behavior genetics and what they mean. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 9 (5), 160–164. https://doi-org.ezproxy.kpu.ca:2443/10.1111/1467-8721.00084

Winch, J. (2012, Mar 08). Genius with a finger on the pulse of discovery: Birmingham-born sir francis galton was a victorian genius. but today he would be thought a racist because of the controversial interest for which he is best remembered – eugenics. jessica winch reports. Birmingham Post. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.kpu.ca:2443/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.kpu.ca:2443/docview/926809806?accountid=35875

Wikipedia. (2019, November 16). Francis Galton. Retrieved November 17, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Galton.

Evolutionary Psychology: Exploring Big Questions Copyright © by kristie. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 January 2022

The future of human behaviour research

- Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier 1 ,

- Jean Burgess 2 , 3 ,

- Maurizio Corbetta 4 , 5 ,

- Kate Crawford 6 , 7 , 8 ,

- Esther Duflo 9 ,

- Laurel Fogarty 10 ,

- Alison Gopnik 11 ,

- Sari Hanafi 12 ,

- Mario Herrero 13 ,

- Ying-yi Hong 14 ,

- Yasuko Kameyama 15 ,

- Tatia M. C. Lee 16 ,

- Gabriel M. Leung 17 , 18 ,

- Daniel S. Nagin 19 ,

- Anna C. Nobre 20 , 21 ,

- Merete Nordentoft 22 , 23 ,

- Aysu Okbay 24 ,

- Andrew Perfors 25 ,

- Laura M. Rival 26 ,

- Cassidy R. Sugimoto 27 ,

- Bertil Tungodden 28 &

- Claudia Wagner 29 , 30 , 31

Nature Human Behaviour volume 6 , pages 15–24 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

59k Accesses

25 Citations

187 Altmetric

Metrics details

Human behaviour is complex and multifaceted, and is studied by a broad range of disciplines across the social and natural sciences. To mark our 5th anniversary, we asked leading scientists in some of the key disciplines that we cover to share their vision of the future of research in their disciplines. Our contributors underscore how important it is to broaden the scope of their disciplines to increase ecological validity and diversity of representation, in order to address pressing societal challenges that range from new technologies, modes of interaction and sociopolitical upheaval to disease, poverty, hunger, inequality and climate change. Taken together, these contributions highlight how achieving progress in each discipline will require incorporating insights and methods from others, breaking down disciplinary silos.

Genuine progress in understanding human behaviour can only be achieved through a multidisciplinary community effort. Five years after the launch of Nature Human Behaviour , twenty-two leading experts in some of the core disciplines within the journal’s scope share their views on pressing open questions and new directions in their disciplines. Their visions provide rich insight into the future of research on human behaviour.

Artificial intelligence

Kate Crawford

Much has changed in artificial intelligence since a small group of mathematicians and scientists gathered at Dartmouth in 1956 to brainstorm how machines could simulate cognition. Many of the domains that those men discussed — such as neural networks and natural language processing — remain core elements of the field today. But what they did not address was the far-reaching social, political, legal and ecological effects of building these systems into everyday life: it was outside their disciplinary view.

Since the mid-2000s, artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly expanded as a field in academia and as an industry, and now a handful of powerful technology corporations deploy these systems at a planetary scale. There have been extraordinary technical innovations, from real-time language translation to predicting the 3D structures of proteins 1 , 2 . But the biggest challenges remain fundamentally social and political: how AI is widening power asymmetries and wealth inequality, and creating forms of harm that need to be prioritized, remedied and regulated.

The most urgent work facing the field today is to research and remediate the costs and consequences of AI. This requires a deeper sociotechnical approach that can contend with the complex effect of AI on societies and ecologies. Although there has been important work done on algorithmic fairness in recent years 3 , 4 , not enough has been done to address how training data fundamentally skew how AI models interpret the world from the outset. Second, we need to address the human costs of AI, which range from discrimination and misinformation to the widespread reliance on underpaid labourers (such as the crowd-workers who train AI systems for as little as US $2 per hour) 5 . Third, there must be a commitment to reversing the environmental costs of AI, including the exceptionally high energy consumption of the current large computational models, and the carbon footprint of building and operating modern tensor processing hardware 6 . Finally, we need strong regulatory and policy frameworks, expanding on the EU’s draft AI Act of 2021.

By building a more interdisciplinary and inclusive AI field, and developing a more rigorous account of the full impacts of AI, we give engineers and regulators alike the tools that they need to make these systems more sustainable, equitable and just.

Kate Crawford is Research Professor at the Annenberg School, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Senior Principal Researcher at Microsoft Research New York, New York, NY, USA; and the Inaugural Visiting Chair of AI and Justice at the École Normale Supérieure, Paris, France.

Anthropology

Laura M. Rival

The field of anthropology faces fundamental questions about its capacity to intervene more effectively in political debates. How can we use the knowledge that we already have to heal the imagined whole while keeping people in synchrony with each other and with the world they aspire to create for themselves and others?

The economic systems that sustain modern life have produced pernicious waste cultures. Globalization has accelerated planetary degradation and global warming through the continuous release of toxic waste. Every day, like millions of others, I dutifully clean and prepare my waste for recycling. I know it is no more than a transitory measure geared to grant manufacturers time to adjust and adapt. Reports that most waste will not be recycled, but dumped or burned, upset me deeply. How can anthropology remain a critical project in the face of such orchestrated cynicism, bad faith and indifference? How should anthropologists deploy their skills and bring a sense of shared responsibility to the task of replenishing the collective will?

To help to find answers to these questions, anthropologists need to radically rethink the ways in which we describe the processes and relations that tie communities to their environments. The extinction of experience (loss of direct contact with nature) that humankind currently suffers is massive, but not irreversible. New forms of storytelling have successfully challenged modernist myths, particularly their homophonic promises 7 . But there remain persistent challenges, such as the seductive and rampant power of one-size-fits-all progress, and the actions of elites, who thrive on emulation, and in doing so fuel run-away consumerism.

To combat these challenges, I simply reassert that ‘nature’ is far from having outlasted its historical utility. Anthropologists must join forces and reanimate their common exploration of the immense possibilities contained in human bodies and minds. No matter how overlooked or marginalized, these natural potentials hold the key to what keeps life going.

Laura M. Rival is Professor of Anthropology of Nature, Society and Development, ODID and SAME, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK .

Communication and media studies

Jean Burgess

The communication and media studies field has historically been animated by technological change. In the process, it has needed to navigate fundamental tensions: communication can be understood as both transmission (of information), and as (social) ritual 8 ; relatedly, media can be understood as both technology and as culture 9 .

The most important technological change over the past decade has been the ‘platformization’ 10 of the media environment. Large digital platforms owned by the world’s most powerful technology companies have come to have an outsized and transformative role in the transmission (distribution) of information, and in mediating social practices (whether major events or intimate daily routines). In response, digital methods have transformed the field. For example, advances in computational techniques enabled researchers to study patterns of communication on social media, leading to disciplinary trends such as the quantitative description of ‘hashtag publics’ in the mid-2010s 11 .

Platforms’ uses of data, algorithms and automation for personalization, content moderation and governance constitute a further major shift, giving rise to new methods (such as algorithmic audits) that go well beyond quantitative description 12 . But platform companies have had a patchy — at times hostile — relationship to independent research into their societal role, leading to data lockouts and even public attacks on researchers. It is important in the interests of public oversight and open science that we coordinate responses to such attempts to suppress research 13 , 14 .

As these processes of digital transformation continue, new connections between the humanities and technical disciplines will be necessary, giving rise to a new wave of methodological innovation. This next phase will also require more hybrid (qualitative and quantitative; computational and critical) methods 15 , not only to get around platform lockouts but also to ensure more careful attention is paid to how the new media technologies are used and experienced in everyday life. Here, innovative approaches such as the use of data donations can both aid the ‘platform observability’ 16 that is essential to accountability, and ensure that our research involves the perspectives of diverse audiences.

Jean Burgess is Professor of Digital Media at the School of Communication and Digital Media Research Centre (DMRC), Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland Australia; and Associate Director at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society (ADM+S), Melbourne, Victoria, Australia .

Computational social science

Claudia Wagner

Computational social science has emerged as a discipline that leverages computational methods and new technologies to collect, model and analyse digital behavioural data in natural environments or in large-scale designed experiments, and combine them with other data sources (such as survey data).

While the community made critical progress in enhancing our understanding about empirical phenomena such as the spread of misinformation 17 and the role of algorithms in curating misinformation 18 , it has focused less on questions about the quality and accessibility of data, the validity, reliability and reusability of measurements, the potential consequences of measurements and the connection between data, measurement and theory.

I see the following opportunities to address these issues.

First, we need to establish privacy-preserving, shared data infrastructures that collect and triangulate survey data with scientifically motivated organic or designed observational data from diverse populations 19 . For example, longitudinal online panels in which participants allow researchers to track their web browsing behaviour and link these traces to their survey answers will not only facilitate substantive research on societal questions but also enable methodological research (for example, on the quality of different data sources and measurement models), and contribute to the reproducibility of computational social science research.

Second, best practices and scientific infrastructures are needed for supporting the development, evaluation and re-use of measurements and the critical reflection on potentially harmful consequences of measurements 20 . Social scientists have developed such best practices and infrastructural support for survey measurements to avoid using instruments for which the validity is unclear or even questionable, and to support the re-usability of survey scales. I believe that practices from survey methodology and other domains, such as the medical industry, can inform our thinking here.

Finally, the fusion of algorithmic and human behaviour invites us to rethink the various ways in which data, measurements and social theories can be connected 20 . For example, product recommendations that users receive are based on measurements of users’ interests and needs: however, users and measurements are not only influenced by those recommendations, but also influence them in turn. As a community we need to develop research designs and environments that help us to systematically enhance our understanding of those feedback loops.

Claudia Wagner is Head of Computational Social Science Department at GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Köln, Germany; Professor for Applied Computational Social Sciences at RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany; and External Faculty Member of the Complexity Science Hub, Vienna, Austria .

Criminology

Daniel S. Nagin

Disciplinary silos in path-breaking science are disappearing. Criminology has had a longstanding tradition of interdisciplinarity, but mostly in the form of an uneasy truce of research from different disciplines appearing side-by-side in leading journals — a scholarly form of parallel play. In the future, this must change because the big unsolved challenges in criminology will require cooperation among all of the social and behavioural sciences.

These challenges include formally merging the macro-level themes emphasized by sociologists with the micro-, individual-level themes emphasized by psychologists and economists. Initial steps have been made by economists who apply game theory to model crime-relevant social interactions, but much remains to be done in building models that explain the formation and destruction of social trust, collective efficacy and norms, as they relate to legal definitions of criminal behaviour.

A second opportunity concerns the longstanding focus of criminology on crimes involving the physical taking of property and interpersonal physical violence. These crimes are still with us, but — as the daily news regularly reports — the internet has opened up broad new frontiers for crime that allow for thefts of property and identities at a distance, forms of extortion and human trafficking at a massive scale (often involving untraceable transactions using financial vehicles such as bitcoin) and interpersonal violence without physical contact. This is a new and largely unexplored frontier for criminological research that criminologists should dive into in collaboration with computer scientists who already are beginning to troll these virgin scholarly waters.

The final opportunity I will note also involves drawing from computer science, the primary home of what has come to be called machine learning. It is important that new generations of criminologists become proficient with machine learning methods and also collaborate with its creators. Machine learning and related statistical methods have wide applicability in both the traditional domains of criminological research and new frontiers. These include the use of prediction tools in criminal justice decision-making, which can aid in crime detection, and the prevention and measuring of crime both online and offline, but also have important implications for equity and fairness due to their consequential nature.

Daniel S. Nagin is Teresa and H. John Heinz III University Professor of Public Policy and Statistics at the Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA .

Behavioural economics

Bertil Tungodden

Behavioural and experimental economics have transformed the field of economics by integrating irrationality and nonselfish motivation in the study of human behaviour and social interaction. A richer foundation of human behaviour has opened many new exciting research avenues, and I here highlight three that I find particularly promising.

Economists have typically assumed that preferences are fixed and stable, but a growing literature, combining field and laboratory experimental approaches, has provided novel evidence on how the social environment shapes our moral and selfish preferences. It has been shown that prosocial role models make people less selfish 21 , that early-childhood education affects the fairness views of children 22 and that grit can be fostered in the correct classroom environment 23 . Such insights are important for understanding how exposure to different institutions and socialization processes influence the intergenerational transmission of preferences, but much more work is needed to gain systematic and robust evidence on the malleability of the many dimensions that shape human behaviour.

The moral mind is an important determinant of human behaviour, but our understanding of the complexity of moral motivation is still in its infancy. A growing literature, using an impartial spectator design in which study participants make consequential choices for others, has shown that people often disagree on what is morally acceptable. An important example is how people differ in their view of what is a fair inequality, ranging from the libertarian fairness view to the strict egalitarian fairness view 24 , 25 . An exciting question for future research is whether such moral differences reflect a concern for other moral values, such as freedom, or irrational considerations.

A third exciting development in behavioural and experimental economics is the growing set of global studies on the foundations of human behaviour 26 , 27 . It speaks to the major concern in the social sciences that our evidence is unrepresentative and largely based on studies with samples from Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic societies 28 . The increased availability of infrastructure for implementing large-scale experimental data collections and methodological advances carry promise that behavioural and experimental economic research will broaden our understanding of the foundations of human behaviour in the coming years.

Bertil Tungodden is Professor and Scientific Director of the Centre of Excellence FAIR at NHH Norwegian School of Economics, Bergen, Norway .

Development economics

Esther Duflo

The past three decades have been a wonderful time for development economics. The number of scholars, the number of publications and the visibility of the work has dramatically increased. Development economists think about education, health, firm growth, mental health, climate, democratic rules and much more. No topic seems off limits!

This progress is intimately connected with the explosion of the use of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and, more generally, with the embrace of careful causal identification. RCTs have markedly transformed development economics and made it the field that it is today.

The past three decades (until the COVID-19 crisis) have also been very good for improving the circumstances of low-income people around the world: poverty rates have fallen; school enrolment has increased; and maternal and infant mortality has been halved. Although I would not dare imply that the two trends are causally related, one of the reasons for these improvements in the quality of life — even in countries where economic growth has been slow — is the greater focus on pragmatic solutions to the fundamental problems faced by people with few resources. In many countries, development economics researchers (particularly those working with RCTs) have been closely involved with policy-makers, helping them to develop, implement and test these solutions. In turn, this involvement has been a fertile ground for new questions, which have enriched the field.

I imagine future change will, once again, come from an unexpected place. One possible driver of innovation will come from this meeting between the requirements of policy and the intellectual ambition of researchers. This means that the new challenges of our planet must (and will) become the new challenges of development economics. Those challenges are, I believe, quite clear: rethinking social protection to be better prepared to face risks such as the COVID-19 pandemic; mitigating, but unfortunately also adapting to, climate changes; curbing pollution; and addressing gender, racial and ethnic inequality.

To address these critical issues, I believe the field will continue to rely on RCTs, but also start using more creatively (descriptively or in combination with RCTs) the huge amount of data that is increasingly available as governments, even in poor countries, digitize their operations. I cannot wait to be surprised by what comes next.

Esther Duflo is The Abdul Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation and Development Economics at the Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge MA, USA; and cofounder and codirector of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) .

Political science

Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier

Political science remains one of the most pluralistic disciplines and we are on the move towards engaged pluralism. This takes us beyond mere tolerance to true, sincere engagement across methods, methodologies, theories and even disciplinary boundaries. Engaged pluralism means doing the hard work of understanding our own research from the multiple perspectives of others.

More data are being collected on human behaviour than ever before and our advances in methods better address the inherent interdependencies of the data across time, space and context. There are new ways to measure human behaviour via text, image and video. Data creation can even go back in time. All these advancements bode well for the potential to better understand and predict behaviour. This ‘data century’ and ‘golden age of methods’ also hold the promise to bridge, not divide, political science, provided that there is engaged methodological pluralism. Qualitative methods provide unique insights and perspectives when joined with quantitative methods, as does a broader conception of the methodologies underlying and launching our research.

I remain a strong proponent of leveraging dynamics and focusing on heterogeneity in our research questions to advance our disciplines. Doing so brings in an explicit perspective of comparison around similarity and difference. Our questions, hypotheses and theories are often made more compelling when considering the dynamics and heterogeneity that emerges when thinking about time and change.

Striving for a better understanding of gender, race and ethnicity is driving deeper and fuller understandings of central questions in the social sciences. The diversity of the research teams themselves across gender, sex, race, ethnicity, first-generation status, religion, ideology, partisanship and cultures also pushes advancement. One area that we need to better support is career diversity. Supporting careers in government, non-profit organizations and industry, as well as academia, for graduate students will enhance our disciplines and accelerate the production of knowledge that changes the world.

Engaged pluralism remains a foundational key to advancement in political science. Engaged pluralism supports critical diversity, equity and inclusion work, strengthens political scientists’ commitment to democratic principles, and encourages civic engagement more broadly. It is an exciting time to be a social scientist.

Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier is Vernal Riffe Professor of Political Science, Professor of Sociology (courtesy) and Distinguished University Professor at the Department of Political Science, Ohio State University, Columbus OH, USA; and immediate past President of the American Political Science Association .

Cognitive psychology

Andrew Perfors

Cognitive psychology excels at understanding questions whose problem-space is well-defined, with precisely specified theories that transparently map onto thoroughly explored experimental paradigms. That means there is a vast gulf between the current state of the art and the richness and complexity of cognition in the real world. The most exciting open questions are about how to bridge that gap without sacrificing rigour and precision. This requires at least three changes.

First, we must move beyond typical experiments. Stimuli must become less artificial, with a naturalistic structure and distribution. Similarly, tasks must become more ecologically valid: less isolated, with more uncertainty, embedded in natural situations and over different time-scales.

Second, we must move beyond considering individuals in isolation. We live in a rich social world and an environment that is heavily shaped by other humans. How we think, learn and act is deeply affected by how other people think and interact with us; cognitive science needs to engage with this more.

Third, we must move beyond the metaphor of humans as computers. Our cognition is deeply intertwined with our emotions, motivations and senses. These are more than just parameters in our minds; they have a complexity and logic of their own, and interact in nontrivial ways with each other and more typical cognitive domains such as learning, reasoning and acting.

How do we make progress on these steps? We need reliable real-world data that are comparable across people and situations, reflect the cognitive processes involved and are not changed by measurement. Technology may help us with this, but challenges surrounding privacy and data quality are huge. Our models and analytic approaches must also grow in complexity — commensurate with the growth in problem and data complexity — without becoming intractable or losing their explanatory power.

Success in this endeavour calls for a different kind of science that is not centred around individual laboratories or small stand-alone projects. The biggest advances will be achieved on the basis of large, rich, real-world datasets from different populations, created and analysed in collaborative teams that span multiple domains, fields and approaches. This requires incentive structures that reward team-focused, slower science and prioritize the systematic construction of reliable knowledge over splashy findings.

Andrew Perfors is Associate Professor and Deputy Director of the Complex Human Data Hub, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia .

Cultural and social psychology

Ying-yi Hong

I am writing this at an exceptional moment in human history. For two years, the world has faced the COVID-19 pandemic and there is no end in sight. Cultural and social psychology are uniquely equipped to understand the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically examining how people, communities and countries are dealing with this extreme global crisis — especially at a time when many parts of the world are already experiencing geopolitical upheaval.

During the pandemic, and across different nations and regions, a diverse set of strategies (and subsequent levels of effectiveness) were used to curb the spread of the disease. In the first year of the pandemic, research revealed that some cultural worldviews — such as collectivism (versus individualism) and tight (versus loose) norms — were positively associated with compliance with COVID-19 preventive measures as well as with fewer infections and deaths 29 , 30 . These worldview differences arguably stem from different perspectives on abiding to social norms and prioritizing the collective welfare over an individual’s autonomy and liberty. Although in the short term it seems that a collectivist or tight worldview has been advantageous, it is unclear whether this will remain the case in the long term. Cultural worldviews are ‘tools’ that individuals use to decipher the meaning of their environment, and are dynamic rather than static 31 . Future research can examine how cultural worldviews and global threats co-evolve.

The pandemic has also amplified the demarcation of national, political and other major social categories. On the one hand, identification with some groups (for example, national identity) was found to increase in-group care and thus a greater willingness to sacrifice personal autonomy to comply with COVID-19 measures 32 . On the other hand, identification with other groups (for example, political parties) widened the ideological divide between groups and drove opposing behaviours towards COVID-19 measures and health outcomes 33 . As we are facing climate change and other pressing global challenges, understanding the role of social identities and how they affect worldviews, cognition and behaviour will be vital. How can we foster more inclusive (versus exclusive) identities that can unite rather than divide people and nations?

Ying-yi Hong is Choh-Ming Li Professor of Management and Associate Dean (Research) at the Department of Management, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China .

Developmental psychology

Alison Gopnik

Developmental psychology is similar to the kind of book or band that, paradoxically, everyone agrees is underrated. On the one hand, children and the people who care for them are often undervalued and overlooked. On the other, since Piaget, developmental research has tackled some of the most profound philosophical questions about every kind of human behaviour. This will only continue into the future.

Psychologists increasingly recognize that the minds of children are not just a waystation or an incomplete version of adult minds. Instead, childhood is a distinct evolutionarily adaptive phase of an organism, with its own characteristic cognitions, emotions and motivations. These characteristics of childhood reflect a different agenda than those of the adult mind — a drive to explore rather than exploit. This drive comes with motivations such as curiosity, emotions such as wonder and surprise and remarkable cognitive learning capacities. A new flood of research on curiosity, for example, shows that children actively seek out the information that will help them to learn the most.

The example of curiosity also reflects the exciting prospects for interdisciplinary developmental science. Machine learning is increasingly using children’s learning as a model, and developmental psychologists are developing more precise models as a result. Curiosity-based AI can illuminate both human and machine intelligence. Collaborations with biology are also exciting: for example, in work on evolutionary ‘life history’ explanations of the effects of adverse experiences on later life, and new research on plasticity and sensitive periods in neuroscience. Finally, children are at the cutting edge of culture, and developmental psychologists increasingly conduct a much wider range of cross-cultural studies.

But perhaps the most important development is that policy-makers are finally starting to realize just how crucial children are to important social issues. Developmental science has shown that providing children with the care that they need can decrease poverty, inequality, disease and violence. But that care has been largely invisible to policy-makers and politicians. Understanding scientifically how caregiving works and how to support it more effectively will be the most important challenge for developmental psychology in the next century.

Alison Gopnik is Professor of Psychology and Affiliate Professor of Philosophy at the Department of Psychology, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA .

Science of science

Cassidy R. Sugimoto

Why study science? The goal of science is to advance knowledge to improve the human condition. It is, therefore, essential that we understand how science operates to maximize efficiency and social good. The metasciences are fields that are devoted to understanding the scientific enterprise. These fields are distinguished by differing epistemologies embedded in their names: the philosophy, history and sociology of science represent canonical metasciences that use theories and methods from their mother disciplines. The ‘science of science’ uses empirical approaches to understand the mechanisms of science. As mid-twentieth-century science historian Derek de Solla Price observed, science of science allows us to “turn the tools of science on science itself” 34 .

Contemporary questions in the science of science investigate, inter alia, catalysts of discovery and innovation, consequences of increased access to scientific information, role of teams in knowledge creation and the implications of social stratification on the scientific enterprise. Investigation of these issues require triangulation of data and integration across the metasciences, to generate robust theories, model on valid assumptions and interpret results appropriately. Community-owned infrastructure and collective venues for communication are essential to achieve these goals. The construction of large-scale science observatories, for example, would provide an opportunity to capture the rapidly expanding dataverse, collaborate and share data, and provide nimble translations of data into information for policy-makers and the scientific community.

The topical foci of the field are also undergoing rapid transformation. The expansion of datasets enables researchers to analyse a fuller population, rather than a narrow sample that favours particular communities. The field has moved from an elitist focus on ‘success’ and ‘impact’ to a more-inclusive and prosopographical perspective. Conversations have shifted from citations, impact factors and h -indices towards responsible indicators, diversity and broader impacts. Instead of asking ‘how can we predict the next Nobel prize winner?’, we can ask ‘what are the consequences of attrition in the scientific workforce?’. The turn towards contextualized measurements that use more inclusive datasets to understand the entire system of science places the science of science in a ripe position to inform policy and propel us towards a more innovative and equitable future.

Cassidy R. Sugimoto is Professor and Tom and Marie Patton School Chair, School of Public Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA .

Sari Hanafi

In the past few years, we have been living through times in which reasonable debate has become impossible. Demagogical times are driven by the vertiginous rise of populism and authoritarianism, which we saw in the triumph of Donald Trump in the USA and numerous other populist or authoritarian leaders in many places around the globe. There are some pressing tasks for sociology that can be, in brief, reduced to three.

First, fostering democracy and the democratization process requires disentangling the constitutive values that compose the liberal political project (personal liberty, equality, moral autonomy and multiculturalism) to address the question of social justice and to accommodate the surge in people’s religiosity in many parts in the globe.

Second, the struggle for the environment is inseparable from our choice of political economy, and from the nature of our desired economic system — and these connections between human beings and nature have never been as intimate as they are now. Past decades saw rapid growth that was based on assumptions of the long-term stability of the fixed costs of raw materials and energy. But this is no longer the case. More recently, financial speculation intensified and profits shrunk, generating distributional conflicts between workers, management, owners and tax authorities. The nature of our economic system is now in acute crisis.

The answer lies in a consciously slow-growing new economy that incorporates the biophysical foundations of economics into its functioning mechanisms. Society and nature cannot continue to be perceived each as differentiated into separate compartments. The spheres of nature, culture, politics, social, economy and religion are indeed traversed by common logics that allow a given society to be encompassed in its totality, exactly as Marcel Mauss 35 did. The logic of power and interests embodied in ‘ Homo economicus ’ prevents us from being able to see the potentiality of human beings to cultivate gift-giving practices as an anthropological foundation innate within social relationships.

Third, there are serious social effects of digitalized forms of labour and the trend of replacing labour with an automaton. Even if digital labour partially reduces the unemployment rate, the lack of social protection for digital labourers would have tremendous effects on future generations.

In brief, it is time to connect sociology to moral and political philosophy to address fundamentally post-COVID-19 challenges.

Sari Hanafi is Professor of Sociology at the American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; and President of the International Sociological Association .

Environmental studies (climate change)

Yasuko Kameyama

Climate change has been discussed for more than 40 years as a multilateral issue that poses a great threat to humankind and ecosystems. Unfortunately, we are still talking about the same issue today. Why can’t we solve this problem, even though scientists pointed out its importance and urgency so many years ago?