We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here . #BlackLivesMatter.

“Therefore this is what the Lord says: ‘I will bring on them a disaster they cannot escape. Although they cry out to me, I will not listen to them.” – Jeremiah 11:11

In Rodney Ascher ’s documentary “ Room 237 ,” four theorists attempt to explain the hidden messages in Stanley Kubrick ’s movie “ The Shining .” The ideas about what the movie is about range from the possible to the downright bizarre. One theory fixates on the possibility that “The Shining” was Kubrick’s way of confessing he faked the landing on the moon footage, and another obsesses over the details of the hedge maze. The other two see evidence that the 1980 film indirectly references either the genocide of Native Americans or the Holocaust.

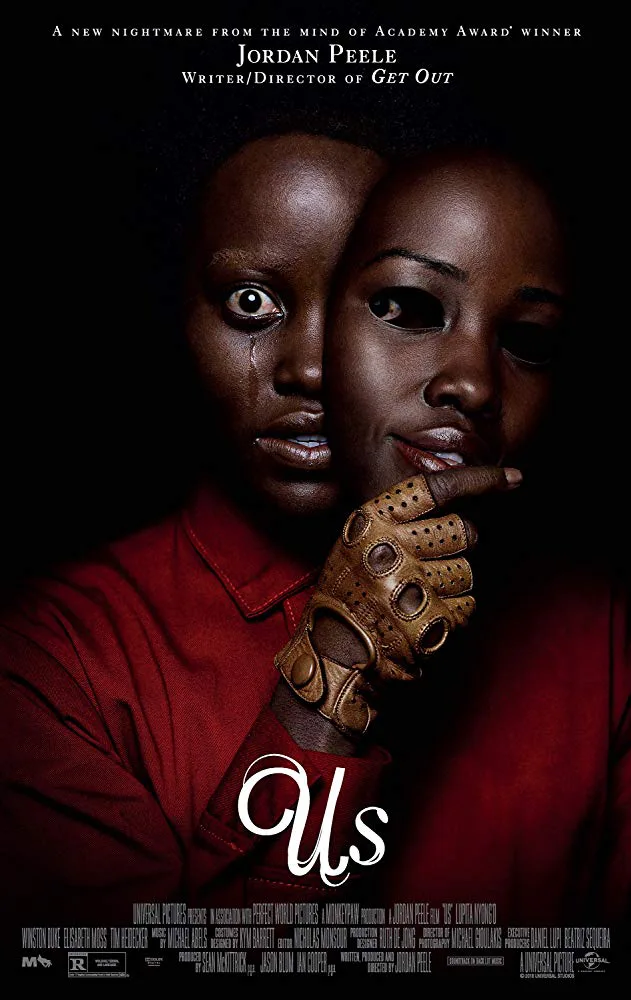

Like “The Shining,” there are a number of different ways to interpret Jordan Peele ’s excellent new horror movie, “Us.” Every image seems to be a clue for what’s about to happen or a stand-in for something outside the main story of a family in danger. Peele’s film, which he directed, wrote and produced, will likely reward audiences on multiple viewings, each visit revealing a new secret, showing you something you missed before in a new light.

“Us” begins back in 1986 with a young girl and her parents wandering through the Santa Cruz boardwalk at night. She separates from them to walk out on the empty beach, watching a foreboding flock of thunderclouds roll in. Her eyes find an attraction just off the main pier, and she walks into what looks like an abandoned hall of mirrors, discovering something deeply terrifying—her doppelgänger. The movie shifts to the present day, with Janelle Monae on the radio as the Wilson family is heading towards their vacation home. The little girl has now grown up to be a woman, Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o), nervous about returning to that spot on the Santa Cruz beach. Her husband, Gabe ( Winston Duke ), thinks her reaction is overblown, but he tries to make her feel at ease so they can take their kids Zora ( Shahadi Wright Joseph ) and Jason ( Evan Alex ) to the beach and meet up with old friends, the Tylers ( Elisabeth Moss and Tim Heidecker ) and their twin daughters. After one small scare and a few strange coincidences on the beach, the family returns home for a quiet night in, only to have their peace broken by a most unlikely set of trespassers lined up across their driveway: doppelgängers of their family.

Part of the appeal of “Us” is how you interpret what all of this information and images mean. No doubt the movie will give audiences plenty to mull over long after the credits. In the film, the Jeremiah 11:11 Bible verse appears twice before pivotal moments, and there are plenty of other Biblical references to dig into, including an analogy to heaven and hell. Perhaps Jason’s “ Jaws ” shirt is a reference to the rocket sweater the little boy wears in “The Shining” or it could be a warning about the film’s oceanside dangers. In the ‘80s scene, when young Adelaide walks into the mysterious attraction, the sign welcoming her is that of a Native American in a headdress above the name “Shaman Vision Quest.” When the family returns to the beach, the sign has been replaced with a more PC-friendly sign bearing a wizard advertising it as “Merlin’s Enchanted Forest,” a bandaid solution to hiding the racist exterior and the horror inside its halls.

As he did with “ Get Out ,” Peele pays significant tribute to the films that have influenced him in “Us.” Though this time, there doesn’t seem to be a consensus. As I spoke with others who saw the movie, we focused on different titles that stood out to us. For me, “The Shining” looked to be the film that received the most nods in “Us,” including an overhead shot of the Wilson family driving through hilly forests to their vacation home, much like the Torrance family does on the way to the Overlook Hotel. There’s also a reference to “The Shining” twins, a few architectural and cinematography similarities and, in one shot, Nyong’o charges the camera with a weapon much like Jack Nicholson menacingly drags along an ax in a chase. However, “Us” is not just a love letter to one horror movie. Peele also pays tribute to Brian De Palma with a split diopter shot that places both Adelaide and her doppelgänger in equal focus for the first time in the movie. There’s also a tip of the hat to Darren Aronofsky ’s “ Black Swan ” in terms of dueling balletic styles and a gorgeously choreographed fight scene that looks like a combative pas de deux.

This delightfully deranged home invasion-family horror film works because Peele not only knows how to tell his story, he assembled an incredible cast to play two roles. The Wilsons are a picture of an all-American family: a family of four that looks to be middle class, with college-educated (Gabe is wearing a Howard University sweater) parents doting on their two children. Their doppelgängers may look like them and be tied to them in some way, but their lives are inverses of each other, and their existence has been one of limits and misery. It’s one of the most poignant analogies of class in America to come out in a studio film in recent memory. For the actors, it’s a chance to play two extremes, one of intense normality and the other of wretched evil. In “Us,” Duke shows off his comedic strengths as the dorky father who often embarrasses his kids, and his doppelgänger is a frighting wall of violence with little to say other than grunts and fighting his adversary. If Nyong’o doesn’t get some professional recognition for her performances here, I will be very disappointed. As Adelaide, she’s fearful, trying to keep some traumatic memories at bay but putting on a brave face for her family. To play her character’s opposite, Nyong’o adopts a graceful, confident movement for her doppelgänger, sliding into the family’s home with scissors at the ready. The doppelgänger looks wide-eyed and maliciously curious as if she’s looking for new ways to terrorize this family. She whispers in a raspy but sinister voice that would make many people jump and run away.

A suspenseful story and marvelous cast need a great crew to make the film a home run, and “Us” is not short on talent. “ It Follows ” cinematographer Mike Gioulakis creates unsettling images in mundane spaces, like how a strange family standing at a driveway isn’t necessarily scary, but when it’s eerily dark out, they’re backlit so that their faces go unseen and the four bodies are standing at a higher elevation from our heroes, so it looks like evil is swooping in from above. Kym Barrett ’s costume designs not only supply the doppelgängers’ nefarious looking red jumpsuits but also the normal, comfy clothes the Wilsons and Tylers wear on vacation. Michael Abels , who also composed the score for “Get Out,” and the ominous notes from the sound design team lay the groundwork for nerve-wracking sequences.

Jordan Peele isn’t the next Kubrick, M. Night Shyamalan, Alfred Hitchcock or Steven Spielberg . He’s his own director, with a vision that melds comedy, horror and social commentary. And he has a visual style that’s luminous, playful and delightfully unnerving. Peele uses an alternate cinematic language to Kubrick, seems more comfortable at teasing his story’s twists throughout the narrative unlike Shyamalan, uses suspense differently than Hitchcock, and possesses the comedic timing Spielberg never had. “Us” is another thrilling exploration of the past and oppression this country is still too afraid to bring up. Peele wants us to talk, and he’s given audiences the material to think, to feel our way through some of the darker sides of the human condition and the American experience.

This review was originally filed from the South by Southwest Film Festival on March 9, 2019.

Monica Castillo

Monica Castillo is a critic, journalist, programmer, and curator based in New York City. She is the Senior Film Programmer at the Jacob Burns Film Center and a contributor to RogerEbert.com .

- Evan Alex as Jason Wilson

- Tim Heidecker as Mr. Tyler

- Winston Duke as Gabriel "Gabe" Wilson

- Kara Hayward as Nancy

- Lupita Nyong’o as Adelaide Wilson

- Shahadi Wright Joseph as Zora Wilson

- Elisabeth Moss as Mrs. Tyler

- Jordan Peele

- Michael Abels

Cinematographer

- Mike Gioulakis

- Nicholas Monsour

Leave a comment

Now playing.

The Remarkable Life of Ibelin

Daddy’s Head

Terrifier 3

Falling Stars

Latest articles

The Steady, Inevitable Decline: Sideways at 20

Bright Wall/Dark Room October 2024: All Hail the Screwball Queen by Olympia Kiriakou

Panic! At the Disco: Body Double at 40

Chicago International Film Festival Pays Tribute to Hirokazu Kore-Eda

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

- Login / Sign Up

With 25 days left, we need your help

The US presidential campaign is in its final weeks and we’re dedicated to helping you understand the stakes. In this election cycle, it’s more important than ever to provide context beyond the headlines. But in-depth reporting is costly, so to continue this vital work, we have an ambitious goal to add 5,000 new members.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

Jordan Peele’s Us — and its ending — explained. Sort of.

The new movie’s conclusion is one elastic metaphor after another. That’s what makes it frustrating. And brilliant.

by Emily St. James

Guess what? Spoilers follow!

First things first: I’m going to give this article a headline that’s something like, “ Us ’s ending, explained” or “ Us ’s ending, dissected,” and I should tell you upfront that I’m not going to explain Us ’s ending. I can’t.

Jordan Peele’s second film has an ending that dares you to bring what you think to it. Where the ending of his first film, Get Out (for which he won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay), was a series of puzzle pieces snapping into place, Us ends in a way that causes the film’s structure to sprawl endlessly. It’s five different puzzles mixed up in the same box, and you only have about 75 percent of the pieces for any of them at best.

- Us is Jordan Peele’s thrilling, blood-curdling allegory about a self-destructing America

But I found that approach incredibly engaging. The audience leaving my screening the other night seemed sharply divided on the film — and its last-minute twist — but I plunged deeper and deeper into it because of that messy, glorious ending.

So let’s talk first about what happens in that ending and how we could read that ending, and then try to find a way to synthesize all of these ideas.

What happens at the end of Us

Us breaks evenly into a classic three-act structure. The first act is all unsettling setup — first with a flashback to our protagonist, Adelaide ( Lupita Nyong’o ), as a young girl, meeting an eerie mirror version of herself, then to the first few days of a family vacation that she takes with her husband ( Winston Duke ) and kids as an adult. The second act follows Adelaide’s and her family’s actions after being menaced by horrifying double versions of themselves — played by the same actors — over the course of one long, gory night.

The second act — roughly the middle hour of the 116-minute film — is pretty much perfect, the kind of expertly pitched horror comedy we see far too rarely. And all along the way, Peele is seeding in exposition, like when we learn that Adelaide and her family aren’t the only ones being menaced by their doubles (who are called “Tethers” in the film, because they’re tethered to their mirror images), and the film cuts away to the vicious murder of two of their friends ( Tim Heidecker and Elisabeth Moss ) by the friends ’ doubles.

Some of this exposition is stated outright, as when Adelaide’s double, Red, explains exactly who she is and who her compatriots are. Other exposition is mostly implied. (Pay close attention, for instance, to whom the Tethers kill and whom they just maim.) And still other stuff is probably just me reading my own opinions into the movie.

Anyway, the third act begins when the family finally makes it to daylight, having killed two of their doubles, with a third double falling right at the top of Act 3. The only Tether left is Red, who absconds with Adelaide’s son, Jason ( Evan Alex ), and races with him down into a gigantic complex of tunnels that exists beneath the Santa Cruz, California, boardwalk and — it’s implied — the entire country.

The tunnels have the feel of an abandoned military facility more than anything else, and they’re filled with rabbits, which have been set free from cages. (The bunnies are the only food the Tethers get.) This vague military feel tracks with something Red tells Adelaide when the two finally face off in what seems to be a classroom. The Tethers were created by a nebulous “them” to control their other selves.

But the experiment was abandoned for unexplained reasons, leaving the Tethers belowground, mimicking our every movement up here, and living lives where they have no free will, lives entirely dictated by our choices. (The long expository monologue where Red basically explains all of this is the movie’s weakest section and kills its momentum. This was also true of the long expository monologue in Get Out !)

The status quo held until Red and Adelaide met as young girls, and the two begin a fight that’s almost a dance but still recognizably a fight. (Peele intercuts this with footage of the teenage Adelaide — a great ballerina — dancing beautifully as Red replicates her actions in a weirdly grotesque mirror belowground.) Finally, Adelaide overcomes Red and kills her. She finds Jason and exits the tunnels.

But aboveground, the many Tethers have joined hands together in a mirror of Hands Across America , the 1986 event meant to raise money and awareness of hunger, which stretched a 6.5 million-person chain (almost all the way) across the Lower 48. The presence of this massive chain of Tethers should hopefully clue in viewers to the film’s final twist. An ad for Hands Across America is one of the last things little Adelaide sees before she goes to the Santa Cruz boardwalk with her parents — which is where she meets Red and (the final scene reveals) is forced to take Red’s place in the Tether world while Red comes up to ours.

The movie never makes clear whether this is long-buried trauma that Adelaide is resurfacing as she and her family ride off into the new, post-apocalyptic landscape of a world where seemingly millions have been murdered by their doubles and a chain of those doubles stands athwart the continent, or whether it’s something she’s pointedly avoided referencing throughout the film. You can make an argument for either.

The movie leaves you with the twist: Adelaide was Red, and Red was Adelaide, and they switched places as young girls. Jason, somehow, seems to realize this in his mother’s eyes, and he looks worried as the scene cuts to the camera tilting over the hills surrounding Santa Cruz — where a long chain of Tethers stretches, presumably from sea to shining sea.

What’s it all mean?

There is no single meaning to the conclusion of Us , and the beauty of it is how elastic its metaphor is

One of the reasons Get Out took off so readily with online theorists was that every single piece of it was crafted to add up to the film’s central revelation about elderly white people literally possessing the bodies of young black people. It was a potent commentary on racial relations, yes, but Peele seeded hints about the big twist into the plot as well. He had clearly thought through every little detail of the movie’s world.

You can’t really say the same for Us . Every time you think you’ve got the movie pinned down to say, “It’s about this!” it slips away from you. Its central metaphor of meeting a literal evil twin of yourself certainly can be read as a commentary on race, but it’s also a pretty brilliant commentary on class, on capitalism, on gender, and on the lasting effects of trauma or mental illness. You can probably add your own possibilities to this list.

All of these concepts keep informing one another. If you want to read what happens to Red and Adelaide as a commentary on how differently traumatic incidents weigh on children of means versus children who grow up with little money, doing so can support both an interpretation of the film as being about mental illness and one where it’s about class.

What’s more, Us doesn’t seem to want to be read as social commentary in the same way Get Out was. That middle hour is so fun precisely because it never really bothers to stop and make you think about the movie’s deeper themes. It’s too busy killing off Tethers by chewing them up in a boat’s motor.

Now, granted, my experience of Us was pretty different from a lot of folks’ experiences (at least from the people I’ve talked to), because I guessed from the first flashback sequence that Red and Adelaide had switched places as kids. I assumed the movie wanted me to figure this out, because it was essentially the only way the movie’s larger plot — the idea that everybody has a Tether, and not just this specific family — could make any sense. Something had to have caused this breach in reality, and the connection between Adelaide and Red seemed the most likely culprit.

Yet it’s honestly remarkable that the movie works as well as it does when you figure out its big twist early on, because Peele does a terrific job of teasing you in ways that make you think maybe you didn’t figure it out, or that the twist is something else entirely. ( Get Out , after all, didn’t really have “a twist” in the way this movie does, only a reveal that happens before the ending.)

Still, set the twist aside, and let’s take Red at her word when it comes to the origin of the Tethers. Some strange experiment produced them, and now they’re a kind of national id, a barely checked shadow self that every American has. (At one point, when asked who she and her family are, Red croaks, “We’re Americans,” which ... fair.)

The natural pushback to this is — it’s preposterous. By giving so much information but still so little, Peele creates a situation where it feels like he’s going to answer all our questions and then just doesn’t. (Credit where it’s due: I love how accurately the whole third act replicates the experience of falling down a particularly disturbing Wikipedia hole at 3 am, right down to somehow finding yourself reading about Hands Across America .)

And yet ... is the twist that preposterous? I don’t literally have a shadow self, but there’s some other person out there in the country right now who could have had my life and career but, instead, has some less comfortable one because he grew up with parents who didn’t have enough money to send him to college, or because he grew up some race other than white, or because he was born a girl, or ... fill in the blank.

Taking Red at her word means believing in an idea that seems self-evidently kooky, but it’s also an idea that drives much of modern society. Capitalism demands that we cling desperately to what we’ve got, and the fear that some dark underbelly might come and rob us of what little we have is always present.

Yet the very idea of society means we’re all tethered together somehow, and the actions of those of us with power and money often make those without either jerk about on puppet strings, even if we never know how what we do affects our doppelgängers.

And all the while, “they” — whoever “they” are — get richer and richer and more powerful.

Thoughts on a universal read of the ending of Us (with apologies to Stanley Kubrick)

But Us isn’t really “about” capitalism, unless you (like me) want to read that into it. The movie’s metaphor is so elastic that you could easily mount a read of the film that says it’s about climate change or the 2016 election or zombies. (In the scenes set in the underground complex especially, Peele plays off the familiar images of zombie films, like legions of people shuffling about, shadows of some life they should otherwise be living.) And I also want to be clear that if you just want to watch Us as a super-fun horror comedy, it is absolutely possible, and you should do that.

But I think you can get to a kind of universal understanding of Us, one that drills down into what the film is about at its core while still leaving room for the elasticity that allows you to read as much or as little into its central metaphor as you’d like. To get there, we have to look at the hall of mirrors that first brings Adelaide and Red together as kids.

In 1986, the hall of mirrors features a stereotypical painting of an American Indian that sits atop its entrance. The art is offensive in the way all thoughtlessness is. Nobody cared who might be hurt by this painting; they just went ahead and painted it. Peele isn’t digging into one of America’s original sins here in the way he alluded to slavery in Get Out , but the evocation of a terrible genocide is at least there .

In 2019, the hall of mirrors has now, clumsily, been converted into one for Merlin the wizard. The inside is the same. Most of the outside is the same. But the painting of the Indian has been replaced — not particularly convincingly — with a painting of Merlin that’s seemingly just been mounted over the old American Indian one. It’s a really good joke, honestly; it’s a spin on how willing modern America is to gloss over the horrors in its past in the name of simply coming up with some other story entirely.

It’s also key to the movie’s more universal read. The hall of mirrors was constructed in the first place as a distillation of tropes around a racially charged stereotype. Just because it’s now ostensibly about Merlin doesn’t mean that it’s no longer built around those darker ideas. You can’t simply scrub away the darker past by putting a more palatable face on it.

America (okay, this is, like, 99.9999 percent on white America) likes to pretend it’s a country without a grim history, that its self-proclaimed exceptionalism makes it free from anything too dark. But, of course, that’s not true. The hall of mirrors was constructed with an American Indian atop it because whoever built it could be reasonably certain no one would care if it was offensive. Those who might care are mostly sequestered on reservations or died generations ago. And you, if you’re an American, live on the land you live on because they died.

(Sidebar: This could also be a really elaborate riff on Peele’s part on The Shining , another horror movie that is occasionally read by some of its hardcore fans through the lens of America’s general inability to deal with the genocide lurking in its root system. Peele has been dressing like The Shining ’s Jack Torrance on the press tour...)

Now consider Hands Across America. The movement did raise some money for hunger — around $34 million — but much of that was eaten up by operational fees, leaving $15 million to be donated to the actual cause. That isn’t chump change, but it’s a drop in the bucket of the problem of actually trying to fight hunger. Is there anything more American than thinking you’ve solved a problem by creating a gigantic spectacle that accomplishes less than you’d think? Again — something dark is covered up by something glossy, and we celebrate the glossy surface.

Us put me in mind of a book I read recently. In The City in the Middle of the Night , the new novel by science fiction author Charlie Jane Anders, the protagonist, Sophie, meets members of an alien species whose telepathic links mean that they are essentially forced to remember everything that has ever happened, stretching back into their distant past. Even when one member of the species dies, that member’s memories are carried forward by those who knew them, and those memories become part of the collective consciousness.

Anders not only shows just how hard this could be for those who don’t quite feel at home in the collective (those who are dealing with huge emotions that they need to understand privately, say), but she also keenly contrasts this species’ long memory with humanity’s short one. Sophie carries the burdens of decisions made millennia before she was born, back on the massive spaceship that brought her ancestors from Earth to this new planet. Those ancestors were shaped by the decisions that you and I are making right now, even as we’re shaped by decisions made hundreds of years ago, and so on. And many of those decisions are now half-remembered dreams.

It is hard to really deal with this, maybe all but impossible. To really sit and think about all of the ways that you are a product of human history, floating through the immense sweep of time and space, rather than someone who can take control of their life and make a difference, is so dispiriting . So we try to gloss over all of that. We put up paintings of Merlin where once paintings of an Indian stood, and we smile and say, “That’s better.” But the painting is still there, underneath the surface. If the aliens Sophie meets in Anders’s novel are doomed to remember, then we, perhaps, are doomed to forget, to pretend that we are more powerful than we are, simply because we’re alive.

This, I think, is why both Anders’s novel and Us spoke so profoundly to me. To try to escape the past is to try to escape yourself. But to try to escape the past is also deeply, deeply human, because to make any progress, we have to find a way to excuse, forgive, or ignore our own faults, to lock them up in a subterranean basement and hope we don’t remain tethered to them forever. But what a fool’s errand that is.

And this reading of the film’s ending, that it was always about the perils of trying to ignore inconvenient truths when they’re looking right back at you in the mirror, is one that unites every other possible reading of the film, too. Race, gender, class, trauma — they’re all covered by the idea that you can have a great life and be a good person but still unknowingly be causing so much suffering.

All of which is to say, when Jason looks at Adelaide late in this movie, seeing, for the first time, his mother’s true self, he’s not realizing that she’s Red, or that she’s Adelaide, or anything like that. He’s realizing that she is, and always has been, both.

More in this stream

Most Popular

- The nightmare facing Democrats, even if Harris wins

- Kamala Harris and the problem with ceding the argument

- How to prepare for growing older if you don’t have kids Member Exclusive

- Why some economists are skeptical of this year’s Nobelists Member Exclusive

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Culture

In the new movie, Sebastian Stan’s Trump is built of grievance and gilding.

They didn’t listen to Hurricane Milton evacuation orders. Then they posted through it.

Laraaji — ambient musician and onetime actor and comic — on laughter, surrender, and transcending the thinking mind.

Everybody’s in LA’s week-long stint is over. It still might point toward the streamer’s future — and the comedian’s.

Essayist and author Meghan O’Gieblyn on the meaning of art in the age of artificial intelligence.

Viral debate videos have become inescapable online.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Review: Jordan Peele’s “Us” Is a Colossal Cinematic Achievement

The success of Jordan Peele’s 2017 film, “ Get Out ,” bought him time, he said, in a recent interview with Le Monde —for his new film, “Us,” he had twice as many shoot days. The expanded time frame allowed him to produce a work of expanded ambition: “Us” bounces back and forth between 1986 and the present day, and its action, compared to “Get Out,” has a vast range—geographical, dramatic, and intellectual. The movie’s imaginative spectrum is enormous, four-dimensionally so: it delves deep into a literal underground world that lends the hallucinatory concept of the “sunken place” from “Get Out” a physical embodiment. And it captures the transformative, radical power of a political conscience, of an idea long held in secret, as it ripens and develops over decades’ worth of time. “Us” is nothing short of a colossal achievement.

Structured like a home-invasion drama, “Us” is a horror film—though saying so is like offering a reminder that “The Godfather” is a gangster film or that “2001: A Space Odyssey” is science fiction. Genre is irrelevant to the merits of a film, whether its conventions are followed or defied; what matters is that Peele cites the tropes and precedents of horror in order to deeply root his film in the terrain of pop culture—and then to pull up those roots. “Us” is a film that places itself within pop culture for diagnostic—and even self-diagnostic—purposes; its subject is, in large measure, cultural consciousness and its counterpart, the cultural unconscious. The crucial element of horror is political and moral—the realities that metaphorical fantasies evoke.

Peele reaches deep into the symbolic DNA of pop culture to discover a hidden, implicit history that he brings to the fore, at a moment of growing recognition that the deeds of the past still rage with silent and devastating force in the present time. After a title card notes the presence of a vast hidden network of tunnels (as for abandoned railways and mines) beneath American soil, the action begins with a bit of pop archeology: a shot of an old-fashioned tube TV set, on which a commercial is playing for “Hands Across America,” a 1986 philanthropic fund-raising event that involved an effort to create a human chain from coast to coast. (The announcer’s voice-over says, “Six million people will tether themselves together to fight hunger in America.”)

At that time, a young girl named Adelaide (though her name isn’t heard until much later in the film, when she’s an adult) is visiting a Santa Cruz beach with her squabbling parents. The child (Madison Curry) wanders off, enters a beachside haunted-house attraction, and, there, walking through a hall of mirrors reminiscent of the one in Orson Welles’s “The Lady from Shanghai,” sees not her reflection but her physical double. After the incident, her parents find her traumatized, but just what happened isn’t clear to them. In the present day, Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o) is married to Gabe Wilson (Winston Duke), and they have two children, Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph), a teen-ager, and Jason (Evan Alex), who seems to be about eight. The Wilsons are prosperous—they’re heading to a summer house by a lake, where Gabe buys a speedboat (albeit a beat-up, run-down one) on a whim. It’s not clear what they do for a living; Adelaide used to dance but gave it up. What is clear is that she now has an aversion to the beach because of the haunted house, which is still there, in a slightly different guise. Her memories and flashbacks suggest that the trauma from whatever happened in the house has haunted her for her whole life.

The Wilsons are black, a fact that, as depicted, has little overt effect on their lives. Avoiding the stereotypes of black Americans in movies, Peele instead knowingly depicts them as a stereotype of a financially successful, socially stable, and cinematically average American family. It’s as though they naturally and unintentionally use what Boots Riley’s film, “Sorry to Bother You,” would call their “white voice,” the voice of white-dominated corporate prosperity. (There’s even a wink back to “Get Out,” regarding the Wilsons’ utterly untroubled confidence in the police.) Their summer companions are a white (and wealthier) family, the Tylers, Kitty (Elisabeth Moss) and Josh (Tim Heidecker), and their twin daughters, Becca (Cali Sheldon) and Lindsey (Noelle Sheldon).

Back at their summer house that night, Adelaide experiences premonitions—she tells Gabe that she feels that her double is out there somewhere. “My whole life I’ve felt as if she’s still coming for me,” she says, and, on this night, she feels as if “she’s getting closer.” Moments later, Jason sees another family standing outside the house; it turns out to be four doubles of the Wilson family, distinguished by their matching red jumpsuits (reminiscent of prison uniforms) and tan sandals, their static posture—holding hands side by side, in the manner of Hands Across America—and their silence. The doubles soon burst into the house, facing off against the Wilsons while Adelaide’s double (named, in the credits, Red)—the only one of the four doppelgängers to speak—states, in a hoarse and halting voice, her demands.

No less than “Get Out,” “Us” is a work of directorial virtuosity, in which Peele invests every moment, every twist, every diabolically conceived and gleefully invoked detail with graphic, psychological resonance and controlled tone, in performance and gesture. Here, as in “Get Out,” Peele employs point-of-view shots to put audience members in the position of the characters, to conjure subjective and fragmentary experience that reverberates with the metaphysical eeriness of their suddenly doubled world. (Recurring nods to Hitchcock’s “The Birds” suggest a mysterious transformation of the natural order.) Exactly as the title promises (and as the drama delivers, when Jason identifies the intruders, saying, “It’s us”), the movie turns the screen into a funhouse mirror in which the distortions prove to be truer representations of the state of things—in the world of its viewers—than more familiar, realistic depictions.

A distinctively American vision is planted throughout the action of “Us,” with an explicit and monitory allusion to the notion of national destiny. As a child, Adelaide sees, at the beach, a silent beachcomber-prophet with a sign that reads “Jeremiah 11:11.” In that chapter, God grants people land on the condition that they keep their covenant with Him, but when they revert to “the sins of their ancestors,” they face divine retribution: “Therefore this is what the Lord says: ‘I will bring on them a disaster they cannot escape. Although they cry out to me, I will not listen to them.’ ” When Adelaide asks the family’s doubles “What are you people?,” the wording of the question (not “who” but “what”) is less offensive than it is literally ontological: Are they alive or dead? Are they zombies or robots or creatures from space or figments of their imagination? Red’s answer is “We’re Americans.” (Even the title, “Us,” doubles as “U.S.”)

“Us” is intensely suspenseful (it would be sinful to spoil its twists or even to hint at its scares) and moderately gory—yet the bloodshed rigorously serves the drama. It’s never there to gross out viewers or to test their threshold of shock or disgust. (And I’m squeamish.) In particular, the explicit violence provides a serious view of life-threatening dangers that compel bourgeois characters to get their hands dirty with the act of killing—it shows what they’re up against and what they have to face, and to do, in an effort to save themselves. Yet “Us” also offers that safety, that salvation, with bitter irony. (It brings to mind Florence Reece’s pro-union song “ Which Side Are You On? ”) It’s a movie that, true to its genre, is plotted with hair-trigger mechanisms that tweak suspense with surprises—intellectual ones along with dramatic and sensory ones.

With its foretold emphasis on tunnels, “Us” proves to be something like Peele’s version of “ Notes from Underground ,” complete with its fiery arias of torment from those whose voices otherwise go unheard. (There’s a relevant wink along the way at Samuel Fuller’s jangling masterwork “ Shock Corridor .”) The term that describes the link between the Wilsons and their doubles is called “tethering”—and that word, in its many grammatical forms, recurs throughout the film (not least, in repeated allusions to Hands Across America). The nature of bonds—social bonds, voluntary and involuntary connections of some people to others—is at the heart of the movie, the desire for solidarity with some, the intended or oblivious dissociation from others.

The movie’s many pop-culture references—whether kids wearing T-shirts for “Thriller” and “Jaws” or the presence of “Good Vibrations” and “Fuck tha Police” on the soundtrack—are no mere decorations. Peele’s radical vision of inequality, of the haves and the have-nots, those who are in and those who are out, is reflected brightly and brilliantly in his view of pop culture, current and classic (including riffs on romantic melodrama and on the notion of emotional expression as a luxury in itself). Mass media is presented in “Us” as a rich people’s culture, if not in the immediate origins of its artists, then in the production, distribution, marketing, platforming, and lawyering of the work—in the very notion of its valuable and ubiquitous legacy. (In the Le Monde interview, Peele cited the soundtrack as another principal benefit of his higher budget.)

“Us” highlights the unwitting complicity of even apparently well-meaning and conscientious people in an unjust order that masquerades as natural and immutable but is, in fact, the product of malevolent designs that leave some languishing in the perma-shadows. (Designed by whom? The movie doesn’t name names, but it winks and nods and nudges in a general direction that runs from the sea to the lake.) It dramatizes this world, but with a twist—one that (avoiding spoilers) risks overturning conventional values and sympathies with ecstatic fervor. Suffice it to say that “Us” reserves empathy for its unwitting villains while gleefully deriding their comfortably normal state of obliviousness—and the ordinary absurdities of the world at large.

The movie’s exquisite perceptiveness and its alluring details are part of a vision that ranges between the outrageously sardonic and the grandly tragic. It renders the movie, for all its suspense, violence, and moral outrage, as much of a joy to recall, moment by moment, as it is to watch. Zora, after wielding an improvised weapon in a desperate, defensive rage, wiggles her arm in fatigue, as if she’d just completed a household chore. Gabe, challenging the doppelgängers with a metal baseball bat, adopts a stereotypical black-dialect voice as if, by doing so, he could make himself more menacing. Jason, suspicious of his own double (named Pluto), crafts a chess-like strategy leading to results and images of anguished grandeur. There are all kinds of magnificently world-built elements that only make sense in the light of big, late reveals, such as a strange and bloody preview, on the Santa Cruz beach, of the Wilson family’s doubles, and Adelaide’s early success as a dancer (and her double’s ability to use it against her).

This world-building has a stark thematic simplicity that both belies and inspires immense complexity. “Us” is a movie that defies the jigsaw-fit, quasi-academic interpretation that pervades recent criticism. As much as the movie offers a metaphorical vision of the enormities of social and political life, it also offers implications of an inner world, a projection of Peele-iana that maps his personal vision onto that of the world at large—and that, in turn, calls upon viewers to receive that world as intensely and consciously and imaginatively as he tries to do. The results of doing so, he suggests, are intrinsically political, even revolutionary.

- Trending on RT

- Best Horror Movies

- More Horror Guides

Jordan Peele's Us Explained: The Big Twists, References, Themes, And Allusions

We're answering the biggest questions you have about jordan peele's idea-stuffed horror smash..

TAGGED AS: Horror

Jordan Peele’s Us broke box office records this weekend with a $70 million start – which means a lot of people saw his terrifying mindf–k of a film and are probably right now going, “huh?” Because Us , unlike most mainstream horror movies, has a helluva lot on its mind. Here we’re going to try and answer a bunch of questions you might have about it, so if you haven’t seen Us , be warned: There is a ton of spoilers ahead .

Where do we even begin? With the big twist that Adelaide ( Lupita Nyong’o ) isn’t actually Adelaide but one of the Tethered? And that rather than protecting her family during the movie, she’s trying to keep her past secret? (Or both!). Or with a breakdown of why Peele chose Hands Across America as a pivotal theme? Maybe with a flick through the Good Book to Jeremiah 11:11?

Below, we’re diving into the movie’s big ideas, and big questions, and shedding some light. But be warned: The more we look, the more questions we find, so please join in this deep Us dissection in the comments, offering up new questions and ever more elaborate theories about Peele’s latest scary puzzler. We will update the piece with new information and theories as we find them, including the best stuff from the comments.

Can you clarify exactly what the “Tethered” Are?

(Photo by @ Universal)

Who the Tethered are is explained, to some extent at least, in two key moments in the movie. There is the fireside chat, in which Red, Adelaide’s double/Tethered, answers Gabe’s ( Winston Duke ) question, “What are you people?” with a “Once upon a time…” tale that reveals that an entity called “they” created the doubles by cloning the population (with the glitch that they hadn’t quite worked out how to clone the soul as well as the body; the soul is split and shared). More is revealed towards the end of the movie when we see, in flashbacks, how the Tethered lived underground – first as bodies intended to control the above-ground population (though there is no explanation as to exactly how that works) and then, once the Tethered were abandoned there, seemingly forced to live a crude reflection of the lives lived by their doubles on the surface.

Who created the Tethered?

It’s never made explicitly clear who exactly created the Tethered, and the “why” – to control the above-ground population – is not really fleshed out. We only hear the creators referred to as “they.” Most theorists believe it’s the government. Not only does the below-ground facility we visit in the film’s climax look and feel government-y, but there are allusions to government control throughout the film, including the moment in the car when Zora ( Shahadi Wright Joseph ) mentions that the government adds fluoride to the water to brainwash the population. Peele said in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter that there is definitely a detailed explanation for how the Tethered came to be, and who made them, but he isn’t sharing anytime soon. “I have a pretty elaborate mythology and history of what’s going on in this film. And of course, the dilemma that comes up is how much of that do you tell?” he said. “When there are questions left, and you know there is more to the story, your imagination is left to run wild.” Mission: Accomplished. We’ll just have to wait for the sequel: Them .

What are the Tethered a metaphor for?

It’s there in the title: us . The obvious point being made in Us is that we are our own worst enemy, so “watch yourself.” Peele said as much in a Q&A following the movie’s premiere at South by Southwest, and elaborated in an interview with the Guardian . “We are our own worst enemy, not just as individuals but more importantly as a group, as a family, as a society, as a country, as a world. We are afraid of the shadowy, mysterious ‘other’ that’s gonna come and kill us and take our jobs and do whatever, but what we’re really afraid of is the thing we’re suppressing: our sin, our guilt, our contribution to our own demise … No one’s taking responsibility for where we’re at. Owning up, blaming ourselves for our part in the problems of the world is something I’m not seeing.” Taking this further, and considering how your sympathies might change on a second viewing – if you’re like us , you may be rooting for Red, who was dragged into a life of servitude – we begin to see some greater truths being revealed in the movie. Is Peele making a point about America’s burying of its past – our collective putting-in-the-dark of the parts of the nation’s history we don’t want to face and, like Adelaide, are determined to keep it in the dark. In the Tethered, Peele seems to say that chance and circumstance are really the only things separating the privileged “us” from the “thems” we fear.

US also means the U.S., right?

Bingo. When asked “What are you people?,” Red answers “We’re Americans” in a line that has been singled out by some critics as being perhaps a bit too on-the-nose. Multiple points seem to be being made here: That the Tethered are Americans, just like us; and that these are our “fellow Americans” who’ve been living this way (just like it’s your fellow Americans who live in poverty).

Do the Tethered exist across the world?

That remains to be seen, but there are suggestions throughout the film that this is a uniquely American phenomenon. There’s Red’s line, “We’re Americans,” and also the overarching theme of “Hands Across America.” Most tellingly, though, is that Adelaide’s plan of escape is to drive along the coast and get to Mexico. Does she know, as a former Tethered, that it’s safe across the border?

What was Hands Across America? And why is it a theme of the movie?

This weekend, Hands Across America is the most highly trafficked Wikipedia page in the world (we presume). But back in 1986, it was a charity event and campaign that was staged on Sunday May 25, that saw some 6.5 million people hold hands and form a human chain across the country (from sea to shining sea, as it says in the ad at the beginning of the film). The way it worked was simple: for a small donation, Americans got a place in the line, and proceeds went to local charities to help the homeless and impoverished. It’s reported that the stunt raised some $34 million.

Why did Peele make it a central theme in his movie? He’s not yet said, but the event has plenty of ties to the film’s themes. There’s the copying/cloning, symbolized by the hand-holding, and the fact that the charity was in support of helping the homeless and underprivileged, the “others” who materialize in Us as the terrifying Tethered. Then there is the fact that ultimately Hands Across America turned out to be something of an empty gesture, a way for those with means to make themselves feel good about themselves but ultimately do little to solve the problem of poverty in the country. After the event, Americans could go back to their everyday lives and forget about their fellow Americans who were suffering. But as the emergence of the Tethered shows, there were others who could not let go of the promise of a better, and equal life.

Why Scissors?

Paper dolls were a big deal around the time of Hands Across America – a few quick snips and you could create a optimistic little piece of craft that spoke to a unified country – and an idea that Adelaide held onto when she was dragged into the underground facility. We see her cutting paper dolls towards the end of the movie, standing by a blackboard, before she slices the paper figures apart. The use of scissors as a weapon in the Tethered attack seems a direct reference to these paper dolls, Hands Across America, and the way scissors can quickly separate two connected things.

UPDATE: Rotten Tomatoes user Danielle also makes an interesting point in the comments, about the duality captured in scissors: “Scissors are made of two blades joined by a single bolt which, when separated, mirror each other’s movements.” Not only then do scissors functionally separate things that are attached, but they also, of themselves, represent the way two like things work together and reflect each other. They’re some kind of physical, stabby, Rorschach Test.

Why the red jump suits and single gloves?

This is pure speculation, as no one has come out and explained the significance of the jump suits or the gloves – or how the Tethered got a hold of so many suits, gloves, and gold scissors for that matter. (Amazon Prime is everywhere .) But a number of online theories suggest the influence of Michael Jackson in the costume choice. When Adelaide is kidnapped and taken down below during the opening sequence (though the actual facts are revealed at the end) she is wearing a “Thriller” t-shirt, which her doppelgänger steals from her before she returns to the surface. Like so many things she connected with before she was dragged below (Hands Across America being the main one), “Thriller” stuck with her. In the song’s famous music video, Jackson is wearing an all-red outfit. The choice to use a single glove on the right hand could also be a nod to Jackson, who often wore a single glove on stage on his right hand. On top of that, Peele could be referencing Freddy Krueger and his famous glove; the killer is one of Peele’s favorite slashers and a VHS of A Nightmare on Elm Street is seen next to the TV in the movie’s opening.

Jeremiah 11: 11

If you, like us, Googled “Jeremiah 11:11” the moment the Us credits rolled, you, like us, probably thought: well, yep, that makes sense. The verse reads: “Therefore thus saith the Lord, Behold, I will bring evil upon them, which they shall not be able to escape; and though they shall cry unto me I will not hearken unto them.” A terrifying evil unleashed and a God who won’t hear our prayers? Yep, that checks out. The verse comes from a passage that also alludes to a people’s past sins and how God’s people had forgotten their own history. The verse is referenced multiple times throughout the movie. First when Adelaide asks for prize number 11, as well as written out on the homeless man’s sign, and later carved into his forehead. (The numbers 11 and 11 appear even earlier, when Adelaide is watching TV, during an ad.) The numbers appear again on the alarm clock at 11:11pm, and on top of the ambulance at the end of the movie.

Update: Another 11:11 sighting comes via Kyle Davidson in the comments: “The Black Flag t-shirt. Their logo is 4 bars which look like IIII (or 1111). The shirt is worn by the employee working the Whack-a-Mole stand in the ’80s and then worn by one of the twins in the present.” Read through the comments section to see what else Kyle has to say about the symbolism of the shirt.

What’s with the rabbits?

When we asked Peele about the rabbits at the Us premiere , he said it was simply that rabbits were scary: “You can tell in their eyes, they have the brain of a sociopath.” But there’s more going on here, we think. There is, of course, some serious Alice in Wonderland vibes – young girl follows white rabbit into another world. But then there is also the notion of rabbits as frequent subjects of scientific experiments. In the opening of the film, Peele cuts from a shot of young Adelaide silent-screaming to a close-up of a caged white rabbit as the credit sequence begins. It’s an obvious clue as to what happened to Adelaide (she was just caged), but also an introduction of the theme of multiplicity (rabbits, they multiply at speed!) and enslavement. Why do the Tethered eat the rabbits? Well, it looks like they have precious few options, and the quick-breeding rabbits make for a sustainable food source.

And what’s with the spiders?

Spiders are another recurring animal motif. First, young Adelaide whistles “Itsy Bitsy Spider” in the hall of mirrors, before young Red takes over the tune; later, as she sits beaten and almost dead in the movie’s climax, real Adelaide attempts to whistle the tune again. It was the last song she heard before she was kidnapped. Why that song? Again: symbolism. The song is about a small spider who tries to climb out of a water spout but is washed back down; later, when the sun comes out and dries up the rain, the spider climbs back up. Kinda like the Tethered, right? Early on we see a kind of visualization of this, as Adelaide watches a small spider crawling out from beneath a big fake spider. The big, fat spider is fake; the little, vulnerable spider is real. Again: symbolism .

And… owls ?

Update: We threw it out to the audience to tell us why they thought Peele chose to have a mechanical owl pop out in the house of mirrors, and they came through with some theories and ideas as to the symbolism. Danielle suggests it was all about foreboding (“Owls are common symbols in literature for evil”), while Gonzalo Lomeli wrote, “Owls are seen as death omens in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and in some Native American tribes. When the owl pops up and scares young Adelaide in the house of mirrors it symbolizes her inevitable fate. When Red (Adelaide’s copy) sees the same owl later, she smashes it to pieces foreshadowing that she will make it out alive.” Kayson Honda suggests, “this might be too on the nose but I was thinking it’s the standard symbol of wisdom, knowledge and truth. Explains why it scared Adelaide as a child but represents her being introduced to the ‘true’ nature of the Tethered. Would also explain why Adelaide symbolically destroys hit when she follows Red back down. Could be seen as a comical poke at how it scared her as a child, or it represents the truth she’s trying desperately to hide.” Whatever the meaning of the owl, it’s interesting to note that one version of Adelaide has a very different reaction to it than the other; the real Adelaide jumps while her doppelgänger has no fear of it.

How much does Jason know?

We learn early on that young Jason ( Evan Alex ) is perceptive and curious (“What does I got five on it mean?”). It’s Jason who seems to work out that the Tethered are controlled by, or control, us, when he plays with his double, Pluto, in the closet; that comes in handy later when he walks Pluto into the fire. At the end of the film, sitting in the passenger seat, he gives his mom a look that suggests he knows something’s not quite right – that she could in fact be one of the Tethered and not the real Adelaide. It’s not 100% clear that he knows this, but there are reasons to believe he has pieced it together. It’s Jason, after all, who witnesses his mother killing one of the Tyler twins and letting out an almost animalistic (and very Tethered-y) sound as she does, and he is in the underground facility when the truth comes out between Adelaide and Red at the movie’s climax. Could he have overheard?

What about the Tethered’s Names? And the family’s?

Biblical and mythological references abound in Peele’s choice of names. Gabriel and his doppelgänger Abraham both bear firmly biblical names, while Jason’s doppelgänger Pluto is named for the Greek god of the underworld and Zora’s Thethered, Umbrae, is named for shadow or darkness. The Tyler twins’ Tethereds’ names also come layered with meaning (Io was the first high priestess of Hera, Nix a Greek goddess of night) and one inventive Rotten Tomatoes staffer wonders if the choice of Adelaide, which is a city in South Australia, was a hint that the character was actually from the underground world (a.k.a., “down under”). This is not true, but we certainly want it to be.

UPDATE: Kitty’s doppelgänger is named Dahlia, which in Hebrew means “flowering branch” and which is also the name of a brightly colored Mexican flower from the daisy family. Interestingly, given the Tylers’ wealth, in Baltic mythology Dalia is the goddess of fate, and is connected with material wealth and its distribution – again a key theme of the movie. And, if you want to read even deeper , many Americans likely associate “Dahlia” with the case of the Black Dahlia, a.k.a. Elizabeth Short, who was found murdered in L.A. in the late 1940s. She had been brutally mutilated and… bisected.

Why is Red the only one who can talk? And why does she talk like that?

That Red can talk is the biggest clue that she is in fact the original Adelaide: none of the other Tethered can talk – though they seem to have a language of grunts and shouts that is communicative, as when Abraham shouts to someone from the boat – so she must have been one of us at some point.

Why does she have such a strained, croaky voice? There are multiple possible explanations. Her trachea might have been broken as a child when her doppelgänger choked her. Her vocal patterns might have blended with the rough noises made by the Tethered with whom she lived. It might be a result of not having spoken for so many years. In an interview with the Hollywood Reporter , Nyong’o refused to reveal the exact source of the character’s voice, but did explain how she achieved it: She based the voice on a real-life condition called spasmodic dysphonia, sometimes the result of trauma. “Your vocal chords involuntarily spasm, creating this odd airflow. I worked with my ENT and a vocal therapist to be able to do it but keep my voice safe, because it’s quite dangerous for a healthy vocal box to do that kind of thing. Then I built off of that.”

Why Couldn’t Kitty’s Doppelgänger Kill Adelaide?

UPDATE: One of the questions we asked in our original post was why couldn’t Kitty’s doppelgänger kill Adelaide? Why did she have her tied to the bed when she could have just stabbed her? Some might argue that it was pure dramatic tension – having the villain looking in the mirror, creepily playing with her face, allowed Peele to get the kids into the room for Zora to put herself in danger, and then Jason to kill Kitty with that fist-pumping crystal attack. RT user mattman suggests two explanations in the comments: “She couldn’t kill Adelaide because if it wasn’t for her, the tethered never would have escaped. Adelaide was important to all the tethers [ sic ].” He also posts: “My other idea comes from Kitty and Adelaide’s conversation earlier in the movie. Kitty is jealous of Adelaide’s beauty. Maybe the tether[ed] also feels that way and was about to pull a Face Off with those scissors.” It’s worth noting that as Kitty’s doppelgänger, Dahlia would have had to endure a bastardized – and presumably quite horrific – reflection of the plastic surgery procedures Kitty had undergone; thus she starts to cut her face maybe in an act of rebellion. Also, containing some part of Kitty’s soul, she might have just been enjoying a moment of vanity with herself in the mirror.

And there are so many more questions. Like:

- Why didn’t young Adelaide just run out of the facility when her cuffs eventually came off?

- What’s exactly happening with the ballet stuff?

- Is Jason potentially one of the Tethered – or different somehow?

- What’s with the rock, paper, scissors players?

- How does Plato’s Allegory of the Cave play into it? (It does, right?)

- What’s with Adelaide snapping off-beat? Is that because Tethered Adelaide can’t actually dance/keep rhythm?

Think you know the answers? Think we got something wrong? Have more questions of your own? Let us know in the comments.

Thumbnail image courtesy @ Universal

Like this? Subscribe to our newsletter and get more features, news, and guides in your inbox every week.

Us (2019) 93%

Related news.

Smile 2 First Reviews: One of the Best Horror Films of the Year

The 10 Scariest Horror Movies Ever

Weekend Box Office: Terrifier 3 Wins Battle of the Killer Clowns

TV Premiere Dates 2024

Renewed and Cancelled TV Shows 2024

Movie & TV News

Featured on rt.

50 Best New Action Movies of 2024

October 16, 2024

Best Horror Movies of the 2020s (So Far)

The 100 Best 2000s Horror Movies

Top Headlines

- 50 Best New Action Movies of 2024 –

- Best Horror Movies of the 2020s (So Far) –

- The 100 Best 2010s Horror Movies –

- The 100 Best 2000s Horror Movies –

- Best New Rom-Coms and Romance Movies –

- 58 Best Basketball Movies, Ranked by Tomatometer –

IMAGES