- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2021

A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases

- Anna Catharina Vieira Armond ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7121-5354 1 ,

- Bert Gordijn 2 ,

- Jonathan Lewis 2 ,

- Mohammad Hosseini 2 ,

- János Kristóf Bodnár 1 ,

- Soren Holm 3 , 4 &

- Péter Kakuk 5

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 50 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

23 Citations

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

The areas of Research Ethics (RE) and Research Integrity (RI) are rapidly evolving. Cases of research misconduct, other transgressions related to RE and RI, and forms of ethically questionable behaviors have been frequently published. The objective of this scoping review was to collect RE and RI cases, analyze their main characteristics, and discuss how these cases are represented in the scientific literature.

The search included cases involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework. A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without language or date restriction. Data relating to the articles and the cases were extracted from case descriptions.

A total of 14,719 records were identified, and 388 items were included in the qualitative synthesis. The papers contained 500 case descriptions. After applying the eligibility criteria, 238 cases were included in the analysis. In the case analysis, fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%), followed by patient safety issues (11.1%) and plagiarism (6.9%). 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities. Paper retraction was the most prevalent sanction (45.4%), followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%).

Conclusions

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields compared to its proportion in scientific publications. The cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of misbehaviors. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations, and from recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Peer Review reports

There has been an increase in academic interest in research ethics (RE) and research integrity (RI) over the past decade. This is due, among other reasons, to the changing research environment with new and complex technologies, increased pressure to publish, greater competition in grant applications, increased university-industry collaborative programs, and growth in international collaborations [ 1 ]. In addition, part of the academic interest in RE and RI is due to highly publicized cases of misconduct [ 2 ].

There is a growing body of published RE and RI cases, which may contribute to public attitudes regarding both science and scientists [ 3 ]. Different approaches have been used in order to analyze RE and RI cases. Studies focusing on ORI files (Office of Research Integrity) [ 2 ], retracted papers [ 4 ], quantitative surveys [ 5 ], data audits [ 6 ], and media coverage [ 3 ] have been conducted to understand the context, causes, and consequences of these cases.

Analyses of RE and RI cases often influence policies on responsible conduct of research [ 1 ]. Moreover, details about cases facilitate a broader understanding of issues related to RE and RI and can drive interventions to address them. Currently, there are no comprehensive studies that have collected and evaluated the RE and RI cases available in the academic literature. This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE consortium to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). Two separate analyses have been conducted. The first analysis uses identified research articles to explore how the literature presents cases of RE and RI, in relation to the year of publication, country, article genre, and violation involved. The second analysis uses the cases extracted from the literature in order to characterize the cases and analyze them concerning the violations involved, sanctions, and field of science.

This scoping review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The full protocol was pre-registered and it is available at https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5bde92120&appId=PPGMS .

Eligibility

Articles with non-fictional case(s) involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, were included. Cases unrelated to scientific activities, research institutions, academic or industrial research and publication were excluded. Articles that did not contain a substantial description of the case were also excluded.

A normative framework consists of explicit rules, formulated in laws, regulations, codes, and guidelines, as well as implicit rules, which structure local research practices and influence the application of explicitly formulated rules. Therefore, if a case involves a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, then it does so on the basis of explicit and/or implicit rules governing RE and RI practice.

Search strategy

A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without any language or date restrictions. Two parallel searches were performed with two sets of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, one for RE and another for RI. The parallel searches generated two sets of data thereby enabling us to analyze and further investigate the overlaps in, differences in, and evolution of, the representation of RE and RI cases in the academic literature. The terms used in the first search were: (("research ethics") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The terms used in the parallel search were: (("research integrity") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The search strategy’s validity was tested in a pilot search, in which different keyword combinations and search strings were used, and the abstracts of the first hundred hits in each database were read (Additional file 1 ).

After searching the databases with these two search strings, the titles and abstracts of extracted items were read by three contributors independently (ACVA, PK, and KB). Articles that could potentially meet the inclusion criteria were identified. After independent reading, the three contributors compared their results to determine which studies were to be included in the next stage. In case of a disagreement, items were reassessed in order to reach a consensus. Subsequently, qualified items were read in full.

Data extraction

Data extraction processes were divided by three assessors (ACVA, PK and KB). Each list of extracted data generated by one assessor was cross-checked by the other two. In case of any inconsistencies, the case was reassessed to reach a consensus. The following categories were employed to analyze the data of each extracted item (where available): (I) author(s); (II) title; (III) year of publication; (IV) country (according to the first author's affiliation); (V) article genre; (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification)[ 7 ]; (X) types of violation (see below); (XI) case description; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case.

Two sets of data were created after the data extraction process. One set was used for the analysis of articles and their representation in the literature, and the other set was created for the analysis of cases. In the set for the analysis of articles, all eligible items, including duplicate cases (cases found in more than one paper, e.g. Hwang case, Baltimore case) were included. The aim was to understand the historical aspects of violations reported in the literature as well as the paper genre in which cases are described and discussed. For this set, the variables of the year of publication (III); country (IV); article genre (V); and types of violation (X) were analyzed.

For the analysis of cases, all duplicated cases and cases that did not contain enough information about particularities to differentiate them from others (e.g. names of the people or institutions involved, country, date) were excluded. In this set, prominent cases (i.e. those found in more than one paper) were listed only once, generating a set containing solely unique cases. These additional exclusion criteria were applied to avoid multiple representations of cases. For the analysis of cases, the variables: (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification); (X) types of violation; (XI) case details; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case were considered.

Article genre classification

We used ten categories to capture the differences in genre. We included a case description in a “news” genre if a case was published in the news section of a scientific journal or newspaper. Although we have not developed a search strategy for newspaper articles, some of them (e.g. New York Times) are indexed in scientific databases such as Pubmed. The same method was used to allocate case descriptions to “editorial”, “commentary”, “misconduct notice”, “retraction notice”, “review”, “letter” or “book review”. We applied the “case analysis” genre if a case description included a normative analysis of the case. The “educational” genre was used when a case description was incorporated to illustrate RE and RI guidelines or institutional policies.

Categorization of violations

For the extraction process, we used the articles’ own terminology when describing violations/ethical issues involved in the event (e.g. plagiarism, falsification, ghost authorship, conflict of interest, etc.) to tag each article. In case the terminology was incompatible with the case description, other categories were added to the original terminology for the same case. Subsequently, the resulting list of terms was standardized using the list of major and minor misbehaviors developed by Bouter and colleagues [ 8 ]. This list consists of 60 items classified into four categories: Study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. (Additional file 2 ).

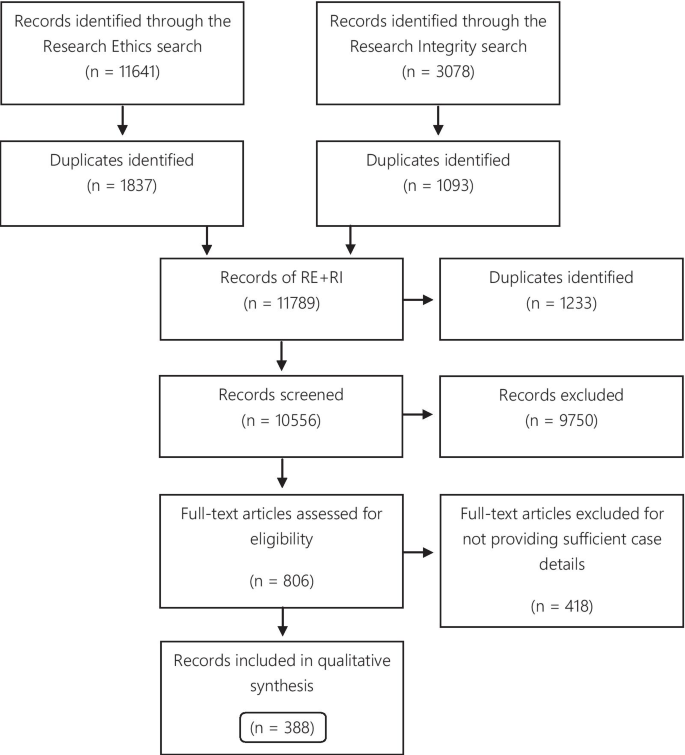

Systematic search

A total of 11,641 records were identified through the RE search and 3078 in the RI search. The results of the parallel searches were combined and the duplicates removed. The remaining 10,556 records were screened, and at this stage, 9750 items were excluded because they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. 806 items were selected for full-text reading. Subsequently, 388 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1 ).

Flow diagram

Of the 388 articles, 157 were only identified via the RE search, 87 exclusively via the RI search, and 144 were identified via both search strategies. The eligible articles contained 500 case descriptions, which were used for the analysis of the publications articles analysis. 256 case descriptions discussed the same 50 cases. The Hwang case was the most frequently described case, discussed in 27 articles. Furthermore, the top 10 most described cases were found in 132 articles (Table 1 ).

For the analysis of cases, 206 (41.2% of the case descriptions) duplicates were excluded, and 56 (11.2%) cases were excluded for not providing enough information to distinguish them from other cases, resulting in 238 eligible cases.

Analysis of the articles

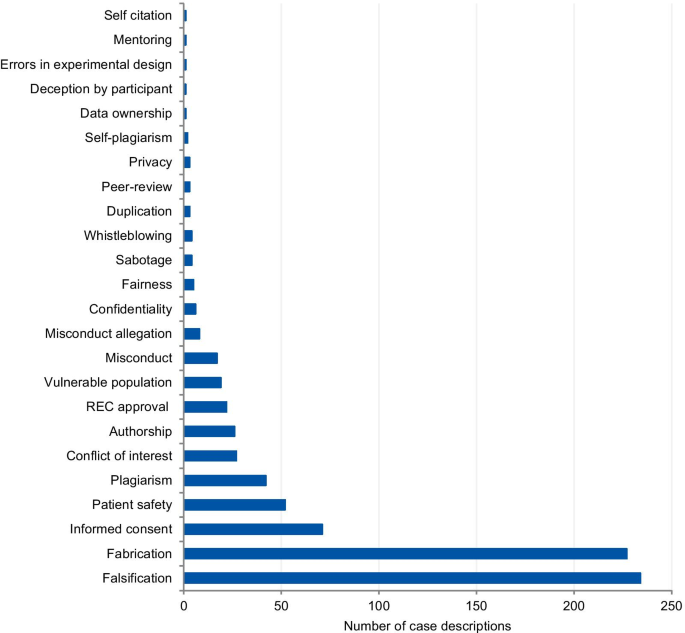

The categories used to classify the violations include those that pertain to the different kinds of scientific misconduct (falsification, fabrication, plagiarism), detrimental research practices (authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, and mentoring), and “other misconduct” (according to the definitions from the National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, [ 1 ]). Each case could involve more than one type of violation. The majority of cases presented more than one violation or ethical issue, with a mean of 1.56 violations per case. Figure 2 presents the frequency of each violation tagged to the articles. Falsification and fabrication were the most frequently tagged violations. The violations accounted respectively for 29.1% and 30.0% of the number of taggings (n = 780), and they were involved in 46.8% and 45.4% of the articles (n = 500 case descriptions). Problems with informed consent represented 9.1% of the number of taggings and 14% of the articles, followed by patient safety (6.7% and 10.4%) and plagiarism (5.4% and 8.4%). Detrimental research practices, such as authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, mentoring, and self-citation were mentioned cumulatively in 7.0% of the articles.

Tagged violations from the article analysis

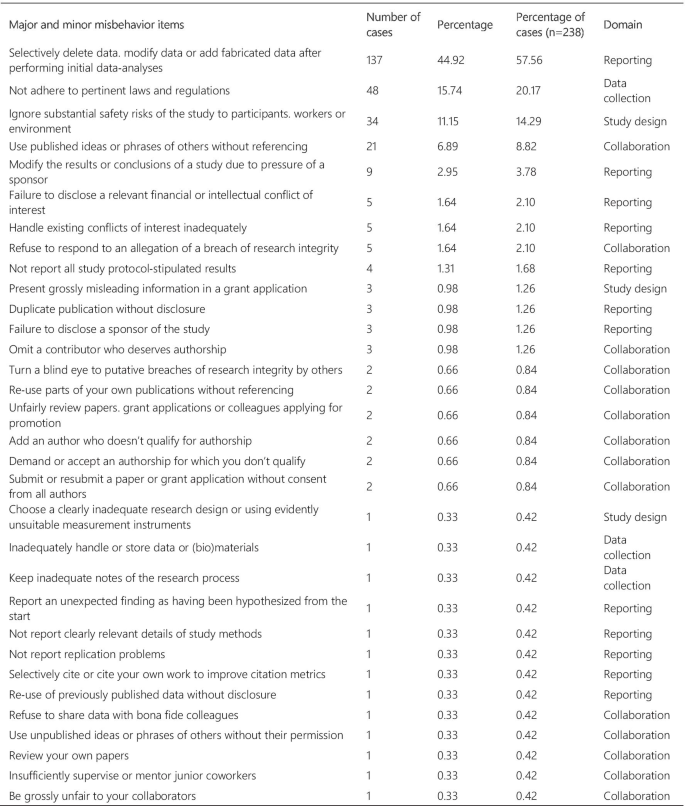

Analysis of the cases

Figure 3 presents the frequency and percentage of each violation found in the cases. Each case could include more than one item from the list. The 238 cases were tagged 305 times, with a mean of 1.28 items per case. Fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%), involved in 57.7% of the cases (n = 238). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%) and involved in 20.2% of the cases. Patient safety issues were the third most frequently tagged violations (11.1%), involved in 14.3% of the cases, followed by plagiarism (6.9% and 8.8%). The list of major and minor misbehaviors [ 8 ] classifies the items into study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. Our results show that 56.0% of the tagged violations involved issues in reporting, 16.4% in data collection, 15.1% involved collaboration issues, and 12.5% in the study design. The items in the original list that were not listed in the results were not involved in any case collected.

Major and minor misbehavior items from the analysis of cases

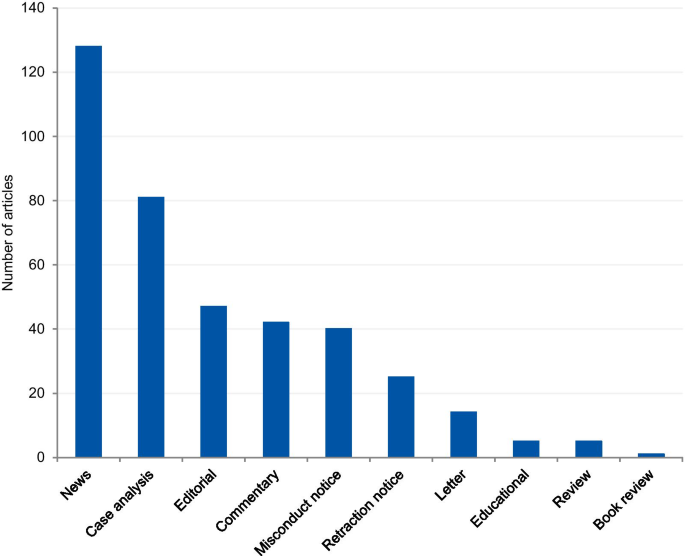

Article genre

The articles were mostly classified into “news” (33.0%), followed by “case analysis” (20.9%), “editorial” (12.1%), “commentary” (10.8%), “misconduct notice” (10.3%), “retraction notice” (6.4%), “letter” (3.6%), “educational paper” (1.3%), “review” (1%), and “book review” (0.3%) (Fig. 4 ). The articles classified into “news” and “case analysis” included predominantly prominent cases. Items classified into “news” often explored all the investigation findings step by step for the associated cases as the case progressed through investigations, and this might explain its high prevalence. The case analyses included mainly normative assessments of prominent cases. The misconduct and retraction notices included the largest number of unique cases, although a relatively large portion of the retraction and misconduct records could not be included because of insufficient case details. The articles classified into “editorial”, “commentary” and “letter” also included unique cases.

Article genre of included articles

Article analysis

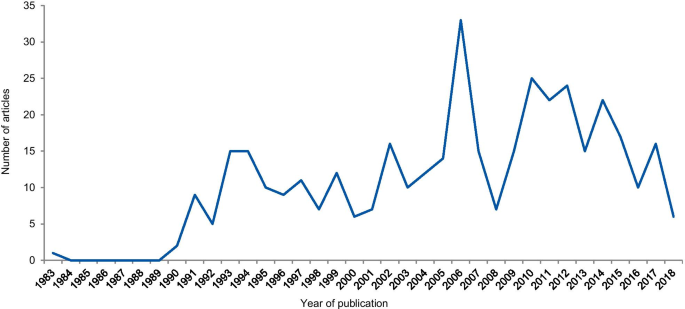

The dates of the eligible articles range from 1983 to 2018 with notable peaks between 1990 and 1996, most probably associated with the Gallo [ 9 ] and Imanishi-Kari cases [ 10 ], and around 2005 with the Hwang [ 11 ], Wakefield [ 12 ], and CNEP trial cases [ 13 ] (Fig. 5 ). The trend line shows an increase in the number of articles over the years.

Frequency of articles according to the year of publication

Case analysis

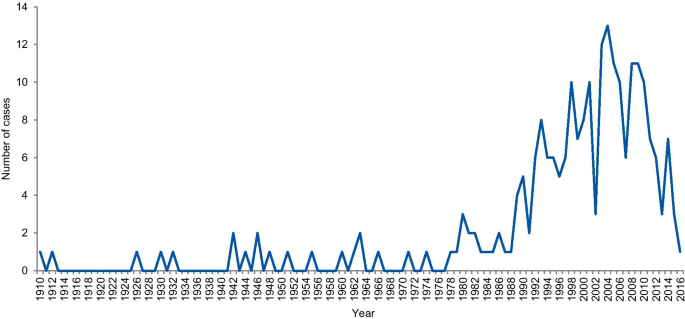

The dates of included cases range from 1798 to 2016. Two cases occurred before 1910, one in 1798 and the other in 1845. Figure 6 shows the number of cases per year from 1910. An increase in the curve started in the early 1980s, reaching the highest frequency in 2004 with 13 cases.

Frequency of cases per year

Geographical distribution

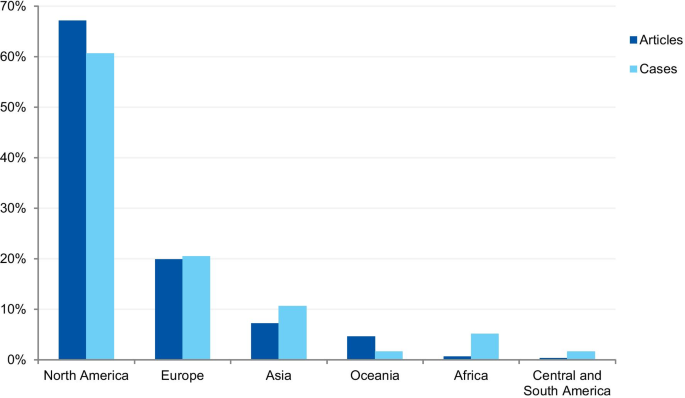

The first analysis concerned the authors’ affiliation and the corresponding author’s address. Where the article contained more than one country in the affiliation list, only the first author’s location was considered. Eighty-one articles were excluded because the authors’ affiliations were not available, and 307 articles were included in the analysis. The articles originated from 26 different countries (Additional file 3 ). Most of the articles emanated from the USA and the UK (61.9% and 14.3% of articles, respectively), followed by Canada (4.9%), Australia (3.3%), China (1.6%), Japan (1.6%), Korea (1.3%), and New Zealand (1.3%). Some of the most discussed cases occurred in the USA; the Imanishi-Kari, Gallo, and Schön cases [ 9 , 10 ]. Intensely discussed cases are also associated with Canada (Fisher/Poisson and Olivieri cases), the UK (Wakefield and CNEP trial cases), South Korea (Hwang case), and Japan (RIKEN case) [ 12 , 14 ]. In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of articles (Fig. 7 ).

Percentage of articles and cases by continent

The case analysis involved the location where the case took place, taking into account the institutions involved in the case. For cases involving more than one country, all the countries were considered. Three cases were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient information. In the case analysis, 40 countries were involved in 235 different cases (Additional file 4 ). Our findings show that most of the reported cases occurred in the USA and the United Kingdom (59.6% and 9.8% of cases, respectively). In addition, a number of cases occurred in Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), China (2.1%), and Germany (2.1%). In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of cases (Fig. 7 ). To enable comparison, we have additionally collected the number of published documents according to country distribution, available on SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ]. The numbers correspond to the documents published from 1996 to 2019. The USA occupies the first place in the number of documents, with 21.9%, followed by China (11.1%), UK (6.3%), Germany (5.5%), and Japan (4.9%).

Field of science

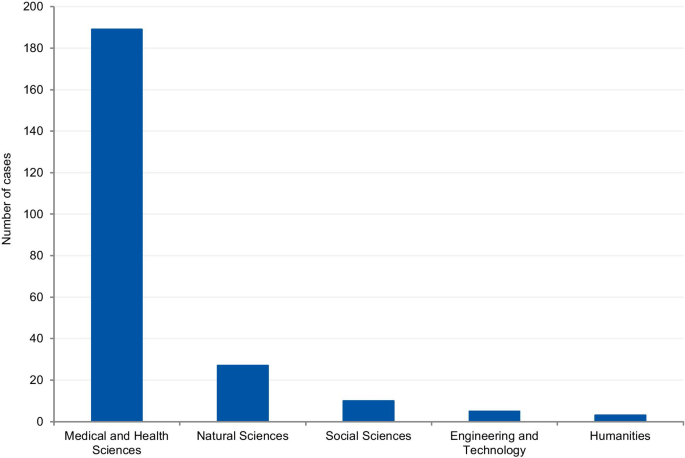

The cases were classified according to the field of science. Four cases (1.7%) could not be classified due to insufficient information. Where information was available, 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities (Fig. 8 ). Additionally, we have retrieved the number of published documents according to scientific field distribution, available on SCImago [ 16 ]. Of the total number of scientific publications, 41.5% are related to natural sciences, 22% to engineering, 25.1% to health and medical sciences, 7.8% to social sciences, 1.9% to agricultural sciences, and 1.7% to the humanities.

Field of science from the analysis of cases

This variable aimed to collect information on possible consequences and sanctions imposed by funding agencies, scientific journals and/or institutions. 97 cases could not be classified due to insufficient information. 141 cases were included. Each case could potentially include more than one outcome. Most of cases (45.4%) involved paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%). (Table 2 ).

RE and RI cases have been increasingly discussed publicly, affecting public attitudes towards scientists and raising awareness about ethical issues, violations, and their wider consequences [ 5 ]. Different approaches have been applied in order to quantify and address research misbehaviors [ 5 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. However, most cases are investigated confidentially and the findings remain undisclosed even after the investigation [ 19 , 20 ]. Therefore, the study aimed to collect the RE and RI cases available in the scientific literature, understand how the cases are discussed, and identify the potential of case descriptions to raise awareness on RE and RI.

We collected and analyzed 500 detailed case descriptions from 388 articles and our results show that they mostly relate to extensively discussed and notorious cases. Approximately half of all included cases was mentioned in at least two different articles, and the top ten most commonly mentioned cases were discussed in 132 articles.

The prominence of certain cases in the literature, based on the number of duplicated cases we found (e.g. Hwang case), can be explained by the type of article in which cases are discussed and the type of violation involved in the case. In the article genre analysis, 33% of the cases were described in the news section of scientific publications. Our findings show that almost all article genres discuss those cases that are new and in vogue. Once the case appears in the public domain, it is intensely discussed in the media and by scientists, and some prominent cases have been discussed for more than 20 years (Table 1 ). Misconduct and retraction notices were exceptions in the article genre analysis, as they presented mostly unique cases. The misconduct notices were mainly found on the NIH repository, which is indexed in the searched databases. Some federal funding agencies like NIH usually publicize investigation findings associated with the research they fund. The results derived from the NIH repository also explains the large proportion of articles from the US (61.9%). However, in some cases, only a few details are provided about the case. For cases that have not received federal funding and have not been reported to federal authorities, the investigation is conducted by local institutions. In such instances, the reporting of findings depends on each institution’s policy and willingness to disclose information [ 21 ]. The other exception involves retraction notices. Despite the existence of ethical guidelines [ 22 ], there is no uniform and a common approach to how a journal should report a retraction. The Retraction Watch website suggests two lists of information that should be included in a retraction notice to satisfy the minimum and optimum requirements [ 22 , 23 ]. As well as disclosing the reason for the retraction and information regarding the retraction process, optimal notices should include: (I) the date when the journal was first alerted to potential problems; (II) details regarding institutional investigations and associated outcomes; (III) the effects on other papers published by the same authors; (IV) statements about more recent replications only if and when these have been validated by a third party; (V) details regarding the journal’s sanctions; and (VI) details regarding any lawsuits that have been filed regarding the case. The lack of transparency and information in retraction notices was also noted in studies that collected and evaluated retractions [ 24 ]. According to Resnik and Dinse [ 25 ], retractions notices related to cases of misconduct tend to avoid naming the specific violation involved in the case. This study found that only 32.8% of the notices identify the actual problem, such as fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism, and 58.8% reported the case as replication failure, loss of data, or error. Potential explanations for euphemisms and vague claims in retraction notices authored by editors could pertain to the possibility of legal actions from the authors, honest or self-reported errors, and lack of resources to conduct thorough investigations. In addition, the lack of transparency can also be explained by the conflicts of interests of the article’s author(s), since the notices are often written by the authors of the retracted article.

The analysis of violations/ethical issues shows the dominance of fabrication and falsification cases and explains the high prevalence of prominent cases. Non-adherence to laws and regulations (REC approval, informed consent, and data protection) was the second most prevalent issue, followed by patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. The prevalence of the five most tagged violations in the case analysis was higher than the prevalence found in the analysis of articles that involved the same violations. The only exceptions are fabrication and falsification cases, which represented 45% of the tagged violations in the analysis of cases, and 59.1% in the article analysis. This disproportion shows a predilection for the publication of discussions related to fabrication and falsification when compared to other serious violations. Complex cases involving these types of violations make good headlines and this follows a custom pattern of writing about cases that catch the public and media’s attention [ 26 ]. The way cases of RE and RI violations are explored in the literature gives a sense that only a few scientists are “the bad apples” and they are usually discovered, investigated, and sanctioned accordingly. This implies that the integrity of science, in general, remains relatively untouched by these violations. However, studies on misconduct determinants show that scientific misconduct is a systemic problem, which involves not only individual factors, but structural and institutional factors as well, and that a combined effort is necessary to change this scenario [ 27 , 28 ].

Analysis of cases

A notable increase in RE and RI cases occurred in the 1990s, with a gradual increase until approximately 2006. This result is in agreement with studies that evaluated paper retractions [ 24 , 29 ]. Although our study did not focus only on retractions, the trend is similar. This increase in cases should not be attributed only to the increase in the number of publications, since studies that evaluated retractions show that the percentage of retraction due to fraud has increased almost ten times since 1975, compared to the total number of articles. Our results also show a gradual reduction in the number of cases from 2011 and a greater drop in 2015. However, this reduction should be considered cautiously because many investigations take years to complete and have their findings disclosed. ORI has shown that from 2001 to 2010 the investigation of their cases took an average of 20.48 months with a maximum investigation time of more than 9 years [ 24 ].

The countries from which most cases were reported were the USA (59.6%), the UK (9.8%), Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), and China (2.1%). When analyzed by continent, the highest percentage of cases took place in North America, followed by Europe, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and Africa. The predominance of cases from the USA is predictable, since the country publishes more scientific articles than any other country, with 21.8% of the total documents, according to SCImago [ 16 ]. However, the same interpretation does not apply to China, which occupies the second position in the ranking, with 11.2%. These differences in the geographical distribution were also found in a study that collected published research on research integrity [ 30 ]. The results found by Aubert Bonn and Pinxten (2019) show that studies in the United States accounted for more than half of the sample collected, and although China is one of the leaders in scientific publications, it represented only 0.7% of the sample. Our findings can also be explained by the search strategy that included only keywords in English. Since the majority of RE and RI cases are investigated and have their findings locally disclosed, the employment of English keywords and terms in the search strategy is a limitation. Moreover, our findings do not allow us to draw inferences regarding the incidence or prevalence of misconduct around the world. Instead, it shows where there is a culture of publicly disclosing information and openly discussing RE and RI cases in English documents.

Scientific field analysis

The results show that 80.8% of reported cases occurred in the medical and health sciences whilst only 1.3% occurred in the humanities. This disciplinary difference has also been observed in studies on research integrity climates. A study conducted by Haven and colleagues, [ 28 ] associated seven subscales of research climate with the disciplinary field. The subscales included: (1) Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) resources, (2) regulatory quality, (3) integrity norms, (4) integrity socialization, (5) supervisor/supervisee relations, (6) (lack of) integrity inhibitors, and (7) expectations. The results, based on the seven subscale scores, show that researchers from the humanities and social sciences have the lowest perception of the RI climate. By contrast, the natural sciences expressed the highest perception of the RI climate, followed by the biomedical sciences. There are also significant differences in the depth and extent of the regulatory environments of different disciplines (e.g. the existence of laws, codes of conduct, policies, relevant ethics committees, or authorities). These findings corroborate our results, as those areas of science most familiar with RI tend to explore the subject further, and, consequently, are more likely to publish case details. Although the volume of published research in each research area also influences the number of cases, the predominance of medical and health sciences cases is not aligned with the trends regarding the volume of published research. According to SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ], natural sciences occupy the first place in the number of publications (41,5%), followed by the medical and health sciences (25,1%), engineering (22%), social sciences (7,8%), and the humanities (1,7%). Moreover, biomedical journals are overrepresented in the top scientific journals by IF ranking, and these journals usually have clear policies for research misconduct. High-impact journals are more likely to have higher visibility and scrutiny, and consequently, more likely to have been the subject of misconduct investigations. Additionally, the most well-known general medical journals, including NEJM, The Lancet, and the BMJ, employ journalists to write their news sections. Since these journals have the resources to produce extensive news sections, it is, therefore, more likely that medical cases will be discussed.

Violations analysis

In the analysis of violations, the cases were categorized into major and minor misbehaviors. Most cases involved data fabrication and falsification, followed by cases involving non-adherence to laws and regulations, patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. When classified by categories, 12.5% of the tagged violations involved issues in the study design, 16.4% in data collection, 56.0% in reporting, and 15.1% involved collaboration issues. Approximately 80% of the tagged violations involved serious research misbehaviors, based on the ranking of research misbehaviors proposed by Bouter and colleagues. However, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis by Fanelli (2009), most self-declared cases involve questionable research practices. In the meta-analysis, 33.7% of scientists admitted questionable research practices, and 72% admitted when asked about the behavior of colleagues. This finding contrasts with an admission rate of 1.97% and 14.12% for cases involving fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism. However, Fanelli’s meta-analysis does not include data about research misbehaviors in its wider sense but focuses on behaviors that bias research results (i.e. fabrication and falsification, intentional non-publication of results, biased methodology, misleading reporting). In our study, the majority of cases involved FFP (66.4%). Overrepresentation of some types of violations, and underrepresentation of others, might lead to misguided efforts, as cases that receive intense publicity eventually influence policies relating to scientific misconduct and RI [ 20 ].

Sanctions analysis

The five most prevalent outcomes were paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications, exclusion from service or position, dismissal and suspension, and paper correction. This result is similar to that found by Redman and Merz [ 31 ], who collected data from misconduct cases provided by the ORI. Moreover, their results show that fabrication and falsification cases are 8.8 times more likely than others to receive funding exclusions. Such cases also received, on average, 0.6 more sanctions per case. Punishments for misconduct remain under discussion, ranging from the criminalization of more serious forms of misconduct [ 32 ] to social punishments, such as those recently introduced by China [ 33 ]. The most common sanction identified by our analysis—paper retraction—is consistent with the most prevalent types of violation, that is, falsification and fabrication.

Publicizing scientific misconduct

The lack of publicly available summaries of misconduct investigations makes it difficult to share experiences and evaluate the effectiveness of policies and training programs. Publicizing scientific misconduct can have serious consequences and creates a stigma around those involved in the case. For instance, publicized allegations can damage the reputation of the accused even when they are later exonerated [ 21 ]. Thus, for published cases, it is the responsibility of the authors and editors to determine whether the name(s) of those involved should be disclosed. On the one hand, it is envisaged that disclosing the name(s) of those involved will encourage others in the community to foster good standards. On the other hand, it is suggested that someone who has made a mistake should have the right to a chance to defend his/her reputation. Regardless of whether a person's name is left out or disclosed, case reports have an important educational function and can help guide RE- and RI-related policies [ 34 ]. A recent paper published by Gunsalus [ 35 ] proposes a three-part approach to strengthen transparency in misconduct investigations. The first part consists of a checklist [ 36 ]. The second suggests that an external peer reviewer should be involved in investigative reporting. The third part calls for the publication of the peer reviewer’s findings.

Limitations

One of the possible limitations of our study may be our search strategy. Although we have conducted pilot searches and sensitivity tests to reach the most feasible and precise search strategy, we cannot exclude the possibility of having missed important cases. Furthermore, the use of English keywords was another limitation of our search. Since most investigations are performed locally and published in local repositories, our search only allowed us to access cases from English-speaking countries or discussed in academic publications written in English. Additionally, it is important to note that the published cases are not representative of all instances of misconduct, since most of them are never discovered, and when discovered, not all are fully investigated or have their findings published. It is also important to note that the lack of information from the extracted case descriptions is a limitation that affects the interpretation of our results. In our review, only 25 retraction notices contained sufficient information that allowed us to include them in our analysis in conformance with the inclusion criteria. Although our search strategy was not focused specifically on retraction and misconduct notices, we believe that if sufficiently detailed information was available in such notices, the search strategy would have identified them.

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields when compared with the volume of publications produced by each field. Moreover, published cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of ethical issues for RE and RI. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations and ethical issues, and recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Availability of data and materials

This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE project in order to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository in https://osf.io/3xatj/?view_only=313a0477ab554b7489ee52d3046398b9 .

National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Fostering integrity in research. National Academies Press; 2017.

Davis MS, Riske-Morris M, Diaz SR. Causal factors implicated in research misconduct: evidence from ORI case files. Sci Eng Ethics. 2007;13(4):395–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-007-9045-2 .

Article Google Scholar

Ampollini I, Bucchi M. When public discourse mirrors academic debate: research integrity in the media. Sci Eng Ethics. 2020;26(1):451–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00103-5 .

Hesselmann F, Graf V, Schmidt M, Reinhart M. The visibility of scientific misconduct: a review of the literature on retracted journal articles. Curr Sociol La Sociologie contemporaine. 2017;65(6):814–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116663807 .

Martinson BC, Anderson MS, de Vries R. Scientists behaving badly. Nature. 2005;435(7043):737–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/435737a .

Loikith L, Bauchwitz R. The essential need for research misconduct allegation audits. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22(4):1027–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9798-6 .

OECD. Revised field of science and technology (FoS) classification in the Frascati manual. Working Party of National Experts on Science and Technology Indicators 2007. p. 1–12.

Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Res Integrity Peer Rev. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 .

Greenberg DS. Resounding echoes of Gallo case. Lancet. 1995;345(8950):639.

Dresser R. Giving scientists their due. The Imanishi-Kari decision. Hastings Center Rep. 1997;27(3):26–8.

Hong ST. We should not forget lessons learned from the Woo Suk Hwang’s case of research misconduct and bioethics law violation. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(11):1671–2. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1671 .

Opel DJ, Diekema DS, Marcuse EK. Assuring research integrity in the wake of Wakefield. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;342(7790):179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2 .

Wells F. The Stoke CNEP Saga: did it need to take so long? J R Soc Med. 2010;103(9):352–6. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k010 .

Normile D. RIKEN panel finds misconduct in controversial paper. Science. 2014;344(6179):23. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.344.6179.23 .

Wager E. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE): Objectives and achievements 1997–2012. La Presse Médicale. 2012;41(9):861–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2012.02.049 .

SCImago nd. SJR — SCImago Journal & Country Rank [Portal]. http://www.scimagojr.com . Accessed 03 Feb 2021.

Fanelli D. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738 .

Steneck NH. Fostering integrity in research: definitions, current knowledge, and future directions. Sci Eng Ethics. 2006;12(1):53–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00022268 .

DuBois JM, Anderson EE, Chibnall J, Carroll K, Gibb T, Ogbuka C, et al. Understanding research misconduct: a comparative analysis of 120 cases of professional wrongdoing. Account Res. 2013;20(5–6):320–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2013.822248 .

National Academy of Sciences NAoE, Institute of Medicine Panel on Scientific R, the Conduct of R. Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process: Volume I. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright (c) 1992 by the National Academy of Sciences; 1992.

Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Flanagin A, Thornton J. Scientific misconduct and medical journals. JAMA. 2018;320(19):1985–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14350 .

COPE Council. COPE Guidelines: Retraction Guidelines. 2019. https://doi.org/10.24318/cope.2019.1.4 .

Retraction Watch. What should an ideal retraction notice look like? 2015, May 21. https://retractionwatch.com/2015/05/21/what-should-an-ideal-retraction-notice-look-like/ .

Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(42):17028–33. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109 .

Resnik DB, Dinse GE. Scientific retractions and corrections related to misconduct findings. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(1):46–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2012-100766 .

de Vries R, Anderson MS, Martinson BC. Normal misbehavior: scientists talk about the ethics of research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics JERHRE. 2006;1(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2006.1.1.43 .

Sovacool BK. Exploring scientific misconduct: isolated individuals, impure institutions, or an inevitable idiom of modern science? J Bioethical Inquiry. 2008;5(4):271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-008-9113-6 .

Haven TL, Tijdink JK, Martinson BC, Bouter LM. Perceptions of research integrity climate differ between academic ranks and disciplinary fields: results from a survey among academic researchers in Amsterdam. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210599 .

Trikalinos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA. Falsified papers in high-impact journals were slow to retract and indistinguishable from nonfraudulent papers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(5):464–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.019 .

Aubert Bonn N, Pinxten W. A decade of empirical research on research integrity: What have we (not) looked at? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2019;14(4):338–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264619858534 .

Redman BK, Merz JF. Scientific misconduct: do the punishments fit the crime? Science. 2008;321(5890):775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158052 .

Bülow W, Helgesson G. Criminalization of scientific misconduct. Med Health Care Philos. 2019;22(2):245–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-018-9865-7 .

Cyranoski D. China introduces “social” punishments for scientific misconduct. Nature. 2018;564(7736):312. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07740-z .

Bird SJ. Publicizing scientific misconduct and its consequences. Sci Eng Ethics. 2004;10(3):435–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-004-0001-0 .

Gunsalus CK. Make reports of research misconduct public. Nature. 2019;570(7759):7. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01728-z .

Gunsalus CK, Marcus AR, Oransky I. Institutional research misconduct reports need more credibility. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1315–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0358 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the EnTIRE research group. The EnTIRE project (Mapping Normative Frameworks for Ethics and Integrity of Research) aims to create an online platform that makes RE+RI information easily accessible to the research community. The EnTIRE Consortium is composed by VU Medical Center, Amsterdam, gesinn. It Gmbh & Co Kg, KU Leuven, University of Split School of Medicine, Dublin City University, Central European University, University of Oslo, University of Manchester, European Network of Research Ethics Committees.

EnTIRE project (Mapping Normative Frameworks for Ethics and Integrity of Research) has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement N 741782. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Behavioural Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Móricz Zsigmond krt. 22. III. Apartman Diákszálló, Debrecen, 4032, Hungary

Anna Catharina Vieira Armond & János Kristóf Bodnár

Institute of Ethics, School of Theology, Philosophy and Music, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Bert Gordijn, Jonathan Lewis & Mohammad Hosseini

Centre for Social Ethics and Policy, School of Law, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Center for Medical Ethics, HELSAM, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Center for Ethics and Law in Biomedicine, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary

Péter Kakuk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors (ACVA, BG, JL, MH, JKB, SH and PK) developed the idea for the article. ACVA, PK, JKB performed the literature search and data analysis, ACVA and PK produced the draft, and all authors critically revised it. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anna Catharina Vieira Armond .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

. Pilot search and search strategy.

Additional file 2

. List of Major and minor misbehavior items (Developed by Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Research integrity and peer review. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 ).

Additional file 3

. Table containing the number and percentage of countries included in the analysis of articles.

Additional file 4

. Table containing the number and percentage of countries included in the analysis of the cases.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Armond, A.C.V., Gordijn, B., Lewis, J. et al. A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases. BMC Med Ethics 22 , 50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00620-8

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2020

Accepted : 21 April 2021

Published : 30 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00620-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Research ethics

- Research integrity

- Scientific misconduct

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Understanding Research Ethics

- First Online: 22 April 2022

Cite this chapter

- Sarah Cuschieri 2

436 Accesses

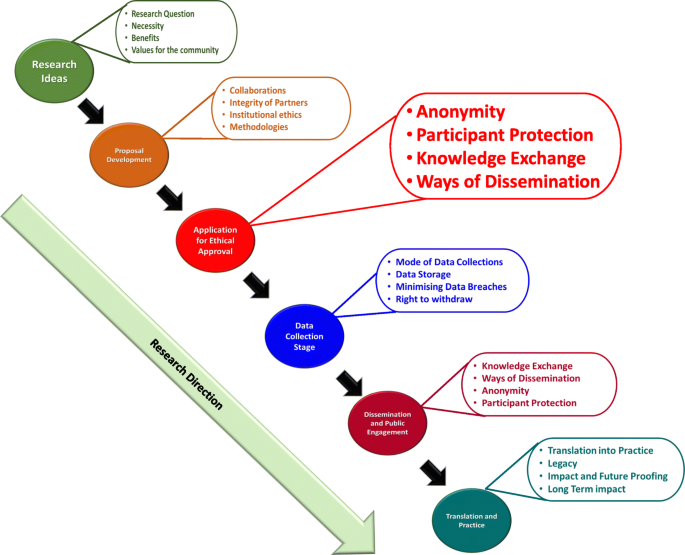

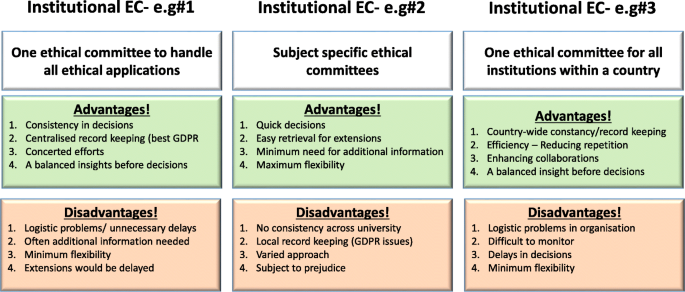

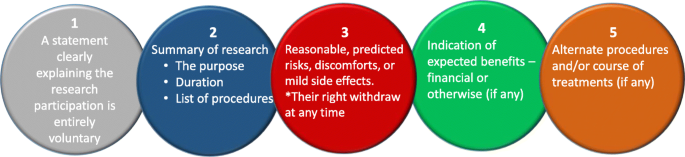

As a researcher, whatever your career stage, you need to understand and practice good research ethics. Moral and ethical principles are requisite in research to ensure no deception or harm to participants, scientific community, and society occurs. Failure to follow such principles leads to research misconduct, in which case the researcher faces repercussions ranging from withdrawal of an article from publication to potential job loss. This chapter describes the various types of research misconduct that you should be aware of, i.e., data fabrication and falsification, plagiarism, research bias, data integrity, researcher and funder conflicts of interest. A sound comprehension of research ethics will take you a long way in your career.

- Research ethics

- Scientific bias

- Conflict of interest

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Malta, Msida, Malta

Sarah Cuschieri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cuschieri, S. (2022). Understanding Research Ethics. In: A Roadmap to Successful Scientific Publishing. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99295-8_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99295-8_2

Published : 22 April 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-99294-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-99295-8

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Research Ethics

Preview this book.

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting / Indexing

- Submission Guidelines

Research Ethics provides a platform for sharing experiences and analysis of ethical issues that are related to the design, conduct, impact and oversight of research. Through open and transparent narrative and analysis of ethical issues in research, it serves to raise awareness, challenge assumptions and help find solutions for complex ethical issues.

Ethical issues are not limited to a specific discipline or type of research. The Editors welcome submissions from any research field (for instance, biomedical, social science, environmental, information technology, or the arts) and a broad range of methodological approaches (for instance, clinical trials, animal experimentation, qualitative studies, laboratory or desk-based research).

Some examples of the topics addressed in Research Ethics include:

- Ethical issues related to the inclusion of vulnerable populations in research

- Ethics dumping

- Benefit sharing

- Ethical issues related to social media research

- Research integrity and research misconduct

- The education and training of researchers and ethics reviewers

- The development and implementation of governance mechanisms

In addition to these applied ethics issues, the journal also welcomes original theoretical papers that contribute to the debate around the normative underpinnings or ethical frameworks for research ethics.

Research Ethics publishes original papers and review articles as well as informative case studies and offers a home for submissions from authors from around the world. The quality of submitted articles is evaluated independently by double-blind peer review. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Research Ethics is aimed at readers and authors who are interested in ethical issues associated with the design and conduct of research, the regulation of research, the procedures and process of ethical review and issues related to scientific integrity. The journal aims to promote, inspire, host and engage in open and public debate about research ethics on an international scale and to contribute to the education of researchers and reviewers of research.

Research Ethics offers a home for submissions from authors from around the world and publishes original papers and review articles as well as informative case studies. The quality of submitted articles is evaluated independently by double-blind peer review.

- Clarivate Analytics: Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI)

- Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ)

- ERIC (Education Resources Information Center)

Manuscript Submission Guidelines: Research Ethics

This Journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics .

Please read the guidelines below then visit the Journal’s submission site http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/rea to upload your manuscript. Please note that manuscripts not conforming to these guidelines may be returned.

Only manuscripts of sufficient quality that meet the aims and scope of Research Ethics will be reviewed.

All articles published in Research Ethics are published fully open access under a Creative Commons licence and available worldwide, with readers having barrier-free access to the full-text articles immediately upon publication. From 1st January 2024, an article processing charge (APC) is levied on all article types that are published in the journal.

For authors that are currently eligible for an Open Access Agreement at your institution with Sage , your article will be published at either no direct cost to you or at a deeply discounted rate, depending on the terms of the agreement.

Authors based at institutions in developing countries may also be eligible for an APC waiver, please see our website page on Gold Open Access Article Processing Charge Waivers for further information. Please refer to our page regarding our partnerships around the world if you would like to know more about the Research4Life initiative.

For authors not eligible for a Sage Open Access Agreement, the APC is USD $500.

- Open Access

- Article processing charge (APC)

- What do we publish? 3.1 Aims & Scope 3.2 Article types 3.3 Writing your paper

- Editorial policies 4.1 Peer review policy 4.2 Authorship 4.3 Acknowledgements 4.4 Declaration of conflicting interests 4.5 Research ethics and patient consent 4.6 Clinical trials

- Publishing policies 5.1 Publication ethics 5.2 Contributor's publishing agreement

- Preparing your manuscript 6.1 Main File 6.2 Title Page 6.3 Formatting 6.4 Language 6.5 Artwork, figures and other graphics 6.6 Supplementary material 6.7 Reference style 6.8 English language editing services

- Submitting your manuscript 7.1 ORCID 7.2 Title, keywords and abstracts 7.3 Information required for completing your submission 7.4 Permissions

- On acceptance and publication 8.1 Sage Production 8.2 Online publication 8.3 Promoting your article

- Further information

1. Open Access

Research Ethics is an open access, peer-reviewed journal. Each article accepted by peer review is made freely available online immediately upon publication, is published under a Creative Commons license and will be hosted online in perpetuity.

For general information on open access at Sage please visit the Open Access page or view our Open Access FAQs.

Back to top

2. Article processing charge (APC)

For authors not eligible for a Sage Open Access Agreement, the article processing charge (APC) is USD $500.

3. What do we publish?

3.1 Aims & Scope

Before submitting your manuscript to Research Ethics , please ensure you have read the Aims & Scope .

3.2 Article Types

Research Ethics publishes original articles and review articles as well as informative case studies on the ethical issues associated with the design and conduct of research, the regulation of research, the procedures and process of ethical review, and issues related to scientific integrity. The journal encourages the submission of the following types of manuscripts:

- Original articles: these manuscripts present original empirical content and/or an original theoretical perspective. Submissions that present original empirical content should not exceed 12,000 words (including references). Submissions that present an original theoretical perspective should not exceed 6,000 words (including references). Longer manuscripts may occasionally be considered at the discretion of the Editors.

- Topic Pieces: these articles are intended to form a snapshot of, or perspective on, contemporary thinking on a topic or issue in research ethics or research integrity. Submissions of topic pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words (including references).

- Case studies: these articles provide examples of real-world ethical challenges in research or research ethics review, as well as real-world case studies in research integrity or research misconduct. Case studies should include ethics analysis of the identified challenges and, where possible, recommendations for dealing with them. Submissions of case studies should be no longer than 3,000 words (including references).

- Review articles: these articles address key issues in research ethics or integrity with a focus on under-researched topics. Rather than introducing new material, review articles offer critical analysis of specific issues in particular areas with significant referencing to existing published literature. Review articles should be between 3,000 and 6,000 words (including references).

3.3 Writing your paper

The Sage Author Gateway has some general advice and on how to get published , plus links to further resources. Sage Author Services also offers authors a variety of ways to improve and enhance their article including English language editing, plagiarism detection, and video abstract and infographic preparation.

3.3.1 Make your article discoverable

When writing up your paper, think about how you can make it discoverable. The title, keywords and abstract are key to ensuring readers find your article through search engines such as Google. For information and guidance on how best to title your article, write your abstract and select your keywords, have a look at this page on the Gateway: How to Help Readers Find Your Article Online .

4. Editorial policies

4 .1 Peer review policy

Manuscripts submitted for publication in Research Ethics are subject to anonymised peer review.

Submissions are initially reviewed by the editors, who determine whether the submission meets the basic guidelines (e.g. addresses a topic relevant to research ethics or research integrity, is written in English, and is sufficiently understandable). If so, the editors will consult among themselves to determine if the submission, based on its quality, should go on to peer review. Submissions passing this first level of review will be assigned to at least two peer reviewers with the appropriate expertise. The reviewers assess submissions based on scholarly quality, relevance, timeliness, novelty, importance, engagement with the relevant literature, and similar factors. Upon receipt of the peer review responses, the editors will decide whether the manuscript should be rejected, or accepted with or without required revisions.

Research Ethics operates a strictly fully anonymous peer review process in which the reviewer’s name is withheld from the author and, the author’s name from the reviewer. The reviewer may at their own discretion opt to reveal their name to the author in their review, but our standard policy practice is for both identities to remain concealed. The desired turnaround time for manuscripts is a maximum of eight weeks from submission to initial decision. If the manuscript is accepted for publication, the editors reserve the right to make minor adjustments (e.g. grammar, tone) and, if necessary, to shorten the manuscript without changing the meaning.

4.2 Authorship

All parties who have made a substantive contribution to the manuscript should be listed as authors. Principal authorship, authorship order, and other publication credits should be based on the relative scientific or professional contributions of the individuals involved, regardless of their status. A student is usually listed as principal author on any multiple-authored publication that substantially derives from the student’s dissertation or thesis. See also the COPE discussion document on authorship, available here .

Please note that AI chatbots and Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, do not currently satisfy our authorship criteria. Use of any AI chatbot or LLM in helping prepare a manuscript for submission should be clearly indicated in the manuscript, including which model was used and for what purpose. Please use the methods or acknowledgements section, as appropriate. For more information see the Sage policy on Use of ChatGPT and Generative AI .

4.3 Acknowledgements

Contributors or advisors who do not meet the criteria for authorship can be listed in an Acknowledgements section. Examples of those who might be acknowledged include a person who provided purely technical help, general support or feedback on an early draft. Please ensure that persons who are acknowledged have given permission for mention in the article and upload their confirmation (as supplementary materials) at submission.

4.3.1 Third party submissions

Where an individual who is not listed as an author submits a manuscript on behalf of the author(s), a statement must be included in the Acknowledgements section of the manuscript and in the accompanying cover letter. The statements must:

- Disclose this type of editorial assistance – including the individual’s name, company and level of input

- Identify any entities that paid for this assistance

- Confirm that the listed authors have authorized the submission of their manuscript via third party and approved any statements or declarations, e.g. conflicting interests, funding, etc.

Where appropriate, Sage reserves the right to deny consideration to manuscripts submitted by a third party rather than by the authors themselves .

4.3.2 Writing assistance

Individuals who provided writing assistance, e.g. from a specialist communications company, do not qualify as authors and so should only be included in the Acknowledgements section. Authors must disclose any writing assistance – including the individual’s name, company and level of input – and identify the entity that paid for this assistance.

It is not necessary to disclose use of language polishing services.

4.4 Declaration of conflicting interests

It is the policy of Research Ethics to require a declaration of conflicting interests from all authors enabling a statement to be carried within the paginated pages of all published articles.

The declaration of conflicting interests must be provided at the submission stage in two ways:

- Authors should provide a full statement disclosing the existence of any financial or non-financial interest within the title page and/or cover letter, which is not sent to reviewers, to detail these and to declare any potential conflicts of interest to the editor.

- Authors should provide a minimal statement (either "The authors declare the existence of a financial/non-financial competing interest" OR "The authors declare no competing interests") within the anonymised manuscript. The minimal statement will be shared with peer-reviewers and must not include any information which may enable the disclosure of author identities.

In addition to any declarations in the submission system, all authors are required to include a ‘Declaration of Conflicting Interests’ statement at the end of their published article using one of the following standard sentences:

- The authors declare the following competing interests.

- The authors declare no competing interests.

For guidance on conflict of interest statements, please see Sage’s Publishing Policies and the ICMJE recommendations here .

4.5 Research ethics and patient approvals

It is the policy of Research Ethics to require a declaration about research ethics approval enabling a statement to be carried within the paginated pages of all published articles. To ensure anonymous peer-review, please include these details on the title page of your submission. This should include the name of the ethics committee that approved the study and, where possible, the date of approval and reference number of the application.

Should research ethics approval not be relevant/required for your study/article, please include a statement to this effect at the submission stage, along with any accompanying evidence if possible (e.g. relevant link to policy position of institution or legal framework clarifying ethics approval is not required or expected for the kind of study/article being submitted). The following standard sentence can be used:

- The authors declare that research ethics approval was not required for this study.

4.5.1 Medical research

Medical research involving human participants or data must be conducted according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki .

Submitted manuscripts should conform to the ICMJE Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals , and all articles reporting on studies involving human participants must state that the relevant ethics committee provided ethics approval (or waived its requirement). Please ensure that you have provided the full name and institution of the ethics committee, in addition to the approval number and date of approval. Please include these details on the title page of your submission. For research articles, authors are also required to state in the methods section whether participants provided informed consent and whether the consent was written or verbal.

Information on informed consent to report on individual cases or case series should be included in the manuscript text. A statement is required regarding whether written informed consent for patient information and images to be published was provided by the participant(s) or a legally authorized representative.

Please also refer to the ICMJE Recommendations for the Protection of Research Participants

4.5.2 Non-medical research involving humans and human data

All manuscripts reporting studies with humans or human data, including studies that involve primary collection of personal data such as surveys or interviews, must state the relevant ethics committee provided (or waived) approval.

If ethics approval was obtained, please provide the name(s) of the ethics committee(s)/IRB(s) plus the approval number(s)/ID(s). If the study received exemption from ethics approval, please provide the name(s) of the ethics committee(s)/IRB(s) or other authorized body and the reason for exemption. If ethics approval was not sought for the present study, please specify why it was not required and cite the relevant guidelines or legislation where applicable, for the benefit of an international readership. Please include these details on the title page of your submission.

For empirical research articles, authors are also required to state in the methods section whether participants provided informed consent and whether the consent was written or verbal.

If you are unsure whether ethics approval is required for your study, please refer to this Editorial .

4.5.3 Animal studies

All manuscripts reporting on studies with animals must provide details of the relevant research ethics approval (or waiver). Please include these details on the title page of your submission.

4.6 Clinical trials

Many Sage journals conform to the ICMJE requirement that clinical trials are registered in a WHO-approved public trials registry at or before the time of first patient enrolment as a condition of consideration for publication. The trial registry name and URL, and registration number must be included at the end of the abstract.

Further to the above, other Sage journals may consider retrospectively registered trials if the justification for late registration is acceptable, consistent with the AllTrials campaign . The trial registry name and URL, and registration number must be included at the end of the abstract.

5. Publishing Policies

5.1 Publication ethics

Sage is committed to upholding the integrity of the academic record. We encourage authors to refer to the Committee on Publication Ethics’ International Standards for Authors and view the Publication Ethics page on the Sage Author Gateway .

5.1.1 Plagiarism

Research Ethics and Sage take issues of copyright infringement, plagiarism or other breaches of best practice in publication very seriously. We seek to protect the rights of our authors and we always investigate claims of plagiarism or misuse of published articles. Equally, we seek to protect the reputation of the journal against malpractice. Submitted articles may be checked with duplication-checking software. Where an article, for example, is found to have plagiarised other work or included third-party copyright material without permission or with insufficient acknowledgement, or where the authorship of the article is contested, we reserve the right to take action including, but not limited to: publishing an erratum or corrigendum (correction); retracting the article; taking up the matter with the head of department or dean of the author's institution and/or relevant academic bodies or societies; or taking appropriate legal action.

5.1.2 Prior publication

If material has been previously published it is not generally acceptable for publication in a Sage journal. However, there are certain circumstances where previously published material can be considered for publication. Please refer to the guidance on the Sage Author Gateway or if in doubt, contact the Editor at the address given below.

5.2 Contributor's publishing agreement

Before publication Sage requires the author as the rights holder to sign a Journal Contributor’s Publishing Agreement. Research Ethics publishes manuscripts under Creative Commons licenses . The standard license for the journal is Creative Commons by Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC), which allows others to re-use the work without permission as long as the work is properly referenced and the use is non-commercial. For more information, you are advised to visit Sage's OA licenses page .

Alternative license arrangements are available, for example, to meet particular funder mandates, made at the author’s request.

6. Preparing your manuscript for submission

You will be asked to upload your anonymised manuscript separately from a title page. Please take note of the requirements for preparation for each of these documents.

6.1 Main file

Your main file is your anonymised manuscript. Please ensure that you do not include any identifiable information in your main manuscript. It will consist of the body of your work plus references. You do not need to include the title or abstract as these will be added during the submission process.

6.2 Title page

Separate from your anonymised manuscript (main file), please also include a separate title page with the following information:

- Name of all the authors with institutional affiliations and contact details

- Ethics approval information

- Conflict of interest information

- Funding information

- Acknowledgements

6.3 Formatting

The preferred format for your manuscript is Word. Files should be submitted in a .doc or .docx file format. Word templates are available on the Manuscript Submission Guidelines page of our Author Gateway. It is preferable that all submissions be typed in sans serif font (e.g. Calibri, Helvetica). Double-spacing is also preferred. Keep formatting simple, and avoid unnecessary advanced word processing features, justification, linked objects, or creating your own symbols.

6.4 Language

All manuscripts must be written in English.

6.4.1 Terminology

Please note that at Research Ethics we actively discourage use of the term ‘research subjects’ when referring to studies that involve human participants. The word ‘subjects’ should only be used when referring to the processing of data (as in ‘data subjects’). As an alternative, please use: humans, persons, participants, research participants or human participants.

6.5 Artwork, figures and other graphics

For guidance on the preparation of illustrations, pictures and graphs in electronic format, please visit Sage’s Manuscript Submission Guidelines .

Figures supplied in colour will appear in colour online.

6.6 Supplementary material

This journal is able to host additional materials online (e.g. datasets, podcasts, videos, images etc) alongside the full-text of the article. For more information please refer to our guidelines on submitting supplementary files .

6.7 Reference style

Research Ethics adheres to the Sage Harvard reference style. View the Sage Harvard guidelines to ensure your manuscript conforms to this reference style.

If you use EndNote to manage references, you can download the Sage Harvard EndNote output file .

6.8 English language editing services

Authors seeking assistance with English language editing, translation, or figure and manuscript formatting to fit the journal’s specifications should consider using Sage Language Services. Visit Sage Language Services on our Journal Author Gateway for further information.

7. Submitting your manuscript

Research Ethics is hosted on Sage Track, a web based online submission and peer review system powered by ScholarOne™ Manuscripts. Visit http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/rea to login and submit your article online.

IMPORTANT: Please check whether you already have an account in the system before trying to create a new one. If you have reviewed or authored for the journal in the past year it is likely that you will have had an account created. For further guidance on submitting your manuscript online please visit ScholarOne Online Help .

As part of our commitment to ensuring an ethical, transparent and fair peer review process Sage is a supporting member of ORCID, the Open Researcher and Contributor ID . ORCID provides a unique and persistent digital identifier that distinguishes researchers from every other researcher, even those who share the same name, and, through integration in key research workflows such as manuscript and grant submission, supports automated linkages between researchers and their professional activities, ensuring that their work is recognized.

The collection of ORCID iDs from corresponding authors is now part of the submission process of this journal. If you already have an ORCID iD you will be asked to associate that to your submission during the online submission process. We also strongly encourage all co-authors to link their ORCID iD to their accounts in our online peer review platforms. It takes seconds to do: click the link when prompted, sign into your ORCID account and our systems are automatically updated. Your ORCID iD will become part of your accepted publication’s metadata, making your work attributable to you and only you. Your ORCID iD is published with your article so that fellow researchers reading your work can link to your ORCID profile, and from there link to your other publications.

If you do not already have an ORCID iD please follow this link to create one or visit our ORCID homepage to learn more.

7.2 Title, keywords and abstracts

Please supply a title, an abstract and keywords to accompany your manuscript. The title, keywords and abstract are key to ensuring readers find your article online through online search engines such as Google. Please refer to the information and guidance on how best to title your article, write your abstract and select your keywords by visiting the Sage Journal Author Gateway for guidelines on How to Help Readers Find Your Article Online.

All manuscripts should include up to 6 keywords (in alphabetical order) and an abstract of up to 250 words, which is a condensation of the manuscript that contains a statement of purpose, a description of the content, argument, or analysis, and a concise summary of conclusions.

7.3 Co-authors