How to Write a Bibliography for a Research Paper

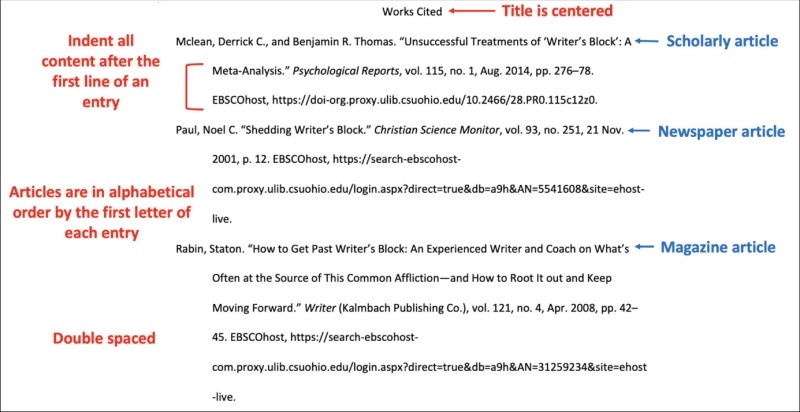

Do not try to “wow” your instructor with a long bibliography when your instructor requests only a works cited page. It is tempting, after doing a lot of work to research a paper, to try to include summaries on each source as you write your paper so that your instructor appreciates how much work you did. That is a trap you want to avoid. MLA style, the one that is most commonly followed in high schools and university writing courses, dictates that you include only the works you actually cited in your paper—not all those that you used.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, assembling bibliographies and works cited.

- If your assignment calls for a bibliography, list all the sources you consulted in your research.

- If your assignment calls for a works cited or references page, include only the sources you quote, summarize, paraphrase, or mention in your paper.

- If your works cited page includes a source that you did not cite in your paper, delete it.

- All in-text citations that you used at the end of quotations, summaries, and paraphrases to credit others for their ideas,words, and work must be accompanied by a cited reference in the bibliography or works cited. These references must include specific information about the source so that your readers can identify precisely where the information came from.The citation entries on a works cited page typically include the author’s name, the name of the article, the name of the publication, the name of the publisher (for books), where it was published (for books), and when it was published.

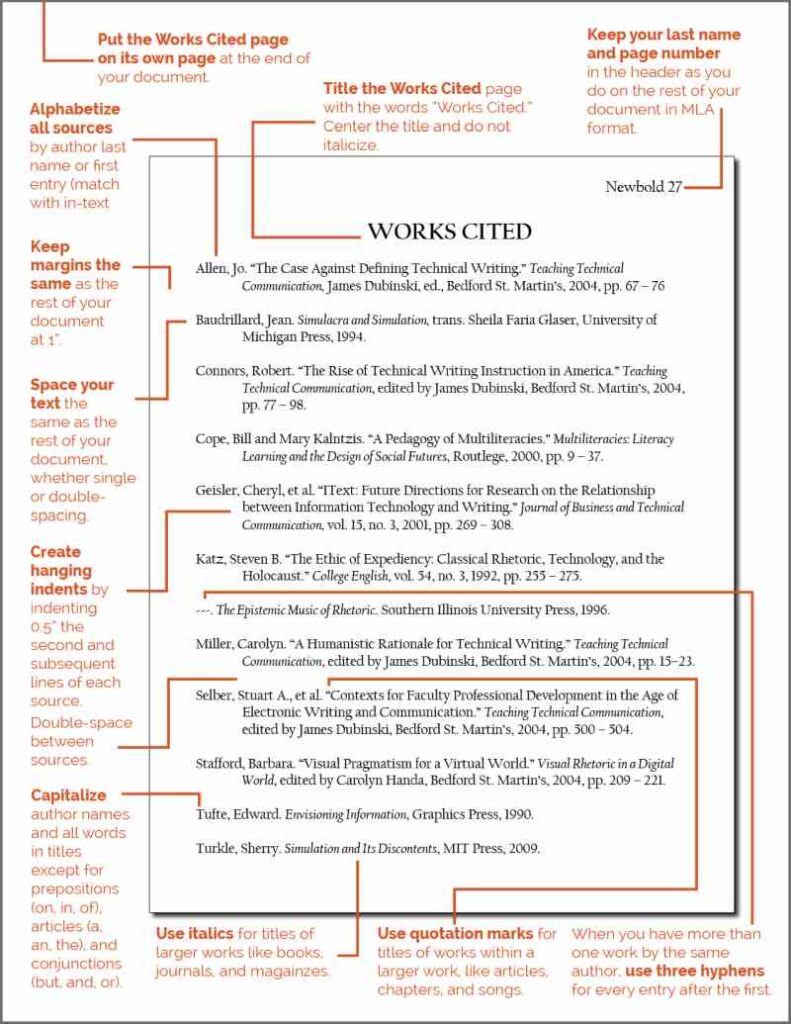

The good news is that you do not have to memorize all the many ways the works cited entries should be written. Numerous helpful style guides are available to show you the information that should be included, in what order it should appear, and how to format it. The format often differs according to the style guide you are using. The Modern Language Association (MLA) follows a particular style that is a bit different from APA (American Psychological Association) style, and both are somewhat different from the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS). Always ask your teacher which style you should use.

A bibliography usually appears at the end of a paper on its own separate page. All bibliography entries—books, periodicals, Web sites, and nontext sources such radio broadcasts—are listed together in alphabetical order. Books and articles are alphabetized by the author’s last name.

Most teachers suggest that you follow a standard style for listing different types of sources. If your teacher asks you to use a different form, however, follow his or her instructions. Take pride in your bibliography. It represents some of the most important work you’ve done for your research paper—and using proper form shows that you are a serious and careful researcher.

Bibliography Entry for a Book

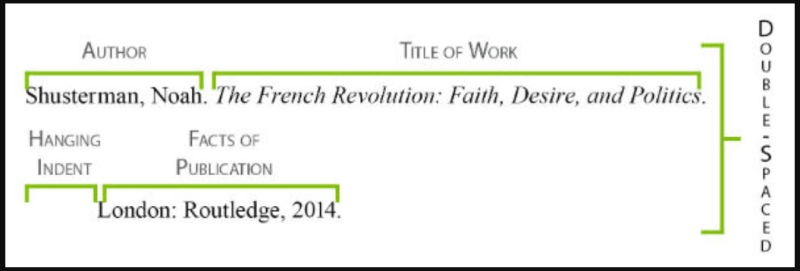

A bibliography entry for a book begins with the author’s name, which is written in this order: last name, comma, first name, period. After the author’s name comes the title of the book. If you are handwriting your bibliography, underline each title. If you are working on a computer, put the book title in italicized type. Be sure to capitalize the words in the title correctly, exactly as they are written in the book itself. Following the title is the city where the book was published, followed by a colon, the name of the publisher, a comma, the date published, and a period. Here is an example:

Format : Author’s last name, first name. Book Title. Place of publication: publisher, date of publication.

- A book with one author : Hartz, Paula. Abortion: A Doctor’s Perspective, a Woman’s Dilemma . New York: Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1992.

- A book with two or more authors : Landis, Jean M. and Rita J. Simon. Intelligence: Nature or Nurture? New York: HarperCollins, 1998.

Bibliography Entry for a Periodical

A bibliography entry for a periodical differs slightly in form from a bibliography entry for a book. For a magazine article, start with the author’s last name first, followed by a comma, then the first name and a period. Next, write the title of the article in quotation marks, and include a period (or other closing punctuation) inside the closing quotation mark. The title of the magazine is next, underlined or in italic type, depending on whether you are handwriting or using a computer, followed by a period. The date and year, followed by a colon and the pages on which the article appeared, come last. Here is an example:

Format: Author’s last name, first name. “Title of the Article.” Magazine. Month and year of publication: page numbers.

- Article in a monthly magazine : Crowley, J.E.,T.E. Levitan and R.P. Quinn.“Seven Deadly Half-Truths About Women.” Psychology Today March 1978: 94–106.

- Article in a weekly magazine : Schwartz, Felice N.“Management,Women, and the New Facts of Life.” Newsweek 20 July 2006: 21–22.

- Signed newspaper article : Ferraro, Susan. “In-law and Order: Finding Relative Calm.” The Daily News 30 June 1998: 73.

- Unsigned newspaper article : “Beanie Babies May Be a Rotten Nest Egg.” Chicago Tribune 21 June 2004: 12.

Bibliography Entry for a Web Site

For sources such as Web sites include the information a reader needs to find the source or to know where and when you found it. Always begin with the last name of the author, broadcaster, person you interviewed, and so on. Here is an example of a bibliography for a Web site:

Format : Author.“Document Title.” Publication or Web site title. Date of publication. Date of access.

Example : Dodman, Dr. Nicholas. “Dog-Human Communication.” Pet Place . 10 November 2006. 23 January 2014 < http://www.petplace.com/dogs/dog-human-communication-2/page1.aspx >

After completing the bibliography you can breathe a huge sigh of relief and pat yourself on the back. You probably plan to turn in your work in printed or handwritten form, but you also may be making an oral presentation. However you plan to present your paper, do your best to show it in its best light. You’ve put a great deal of work and thought into this assignment, so you want your paper to look and sound its best. You’ve completed your research paper!

Back to How To Write A Research Paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- Utility Menu

fa3d988da6f218669ec27d6b6019a0cd

A publication of the harvard college writing program.

Harvard Guide to Using Sources

- The Honor Code

- Bibliography

If you are using Chicago style footnotes or endnotes, you should include a bibliography at the end of your paper that provides complete citation information for all of the sources you cite in your paper. Bibliography entries are formatted differently from notes. For bibliography entries, you list the sources alphabetically by last name, so you will list the last name of the author or creator first in each entry. You should single-space within a bibliography entry and double-space between them. When an entry goes longer than one line, use a hanging indent of .5 inches for subsequent lines. Here’s a link to a sample bibliography that shows layout and spacing . You can find a sample of note format here .

Complete note vs. shortened note

Here’s an example of a complete note and a shortened version of a note for a book:

1. Karen Ho, Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 27-35.

1. Karen Ho, Liquidated , 27-35.

Note vs. Bibliography entry

The bibliography entry that corresponds with each note is very similar to the longer version of the note, except that the author’s last and first name are reversed in the bibliography entry. To see differences between note and bibliography entries for different types of sources, check this section of the Chicago Manual of Style .

For Liquidated , the bibliography entry would look like this:

Ho, Karen, Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street . Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

Citing a source with two or three authors

If you are citing a source with two or three authors, list their names in your note in the order they appear in the original source. In the bibliography, invert only the name of the first author and use “and” before the last named author.

1. Melissa Borja and Jacob Gibson, “Internationalism with Evangelical Characteristics: The Case of Evangelical Responses to Southeast Asian Refugees,” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 17, no. 3 (2019): 80-81, https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2019.1643983 .

Shortened note:

1. Borja and Gibson, “Internationalism with Evangelical Characteristics,” 80-81.

Bibliography:

Borja, Melissa, and Jacob Gibson. “Internationalism with Evangelical Characteristics: The Case of Evangelical Responses to Southeast Asian Refugees.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 17. no. 3 (2019): 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2019.1643983 .

Citing a source with more than three authors

If you are citing a source with more than three authors, include all of them in the bibliography, but only include the first one in the note, followed by et al. ( et al. is the shortened form of the Latin et alia , which means “and others”).

1. Justine M. Nagurney, et al., “Risk Factors for Disability After Emergency Department Discharge in Older Adults,” Academic Emergency Medicine 27, no. 12 (2020): 1271.

Short version of note:

1. Justine M. Nagurney, et al., “Risk Factors for Disability,” 1271.

Nagurney, Justine M., Ling Han, Linda Leo‐Summers, Heather G. Allore, Thomas M. Gill, and Ula Hwang. “Risk Factors for Disability After Emergency Department Discharge in Older Adults.” Academic Emergency Medicine 27, no. 12 (2020): 1270–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14088 .

Citing a book consulted online

If you are citing a book you consulted online, you should include a URL, DOI, or the name of the database where you found the book.

1. Karen Ho, Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 27-35, https://doi-org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/10.1215/9780822391371 .

Bibliography entry:

Ho, Karen. Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street . Durham: Duke University Press, 2009. https://doi-org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/10.1215/9780822391371 .

Citing an e-book consulted outside of a database

If you are citing an e-book that you accessed outside of a database, you should indicate the format. If you read the book in a format without fixed page numbers (like Kindle, for example), you should not include the page numbers that you saw as you read. Instead, include chapter or section numbers, if possible.

1. Karen Ho, Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), chap. 2, Kindle.

Ho, Karen. Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street . Durham: Duke University Press, 2009. Kindle.

- Citation Management Tools

- In-Text Citations

- Examples of Commonly Cited Sources

- Frequently Asked Questions about Citing Sources in Chicago Format

- Sample Bibliography

PDFs for This Section

- Citing Sources

- Online Library and Citation Tools

What is Bibliography?: Meaning, Types, and Importance

A bibliography is a fundamental component of academic research and writing that serves as a comprehensive list of sources consulted and referenced in a particular work. It plays a crucial role in validating the credibility and reliability of the information presented by providing readers with the necessary information to locate and explore the cited sources. A well-constructed bibliography not only demonstrates the depth and breadth of research undertaken but also acknowledges the intellectual contributions of others, ensuring transparency and promoting the integrity of scholarly work. By including a bibliography, writers enable readers to delve further into the subject matter, engage in critical analysis, and build upon existing knowledge.

1.1 What is a Bibliography?

A bibliography is a compilation of sources that have been utilized in the process of researching and writing a piece of work. It serves as a comprehensive list of references, providing information about the various sources consulted, such as books, articles, websites, and other materials. The purpose of a bibliography is twofold: to give credit to the original authors or creators of the sources used and to allow readers to locate and access those sources for further study or verification. A well-crafted bibliography includes essential details about each source, including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication date, and publication information. By having a bibliography, writers demonstrate the extent of their research, provide a foundation for their arguments, and enhance the credibility and reliability of their work.

1.2 Types of Bibliography.

The bibliography is a multifaceted discipline encompassing different types, each designed to serve specific research purposes and requirements. These various types of bibliographies provide valuable tools for researchers, scholars, and readers to navigate the vast realm of literature and sources available. From comprehensive overviews to specialized focuses, the types of bibliographies offer distinct approaches to organizing, categorizing, and presenting information. Whether compiling an exhaustive list of sources, providing critical evaluations, or focusing on specific subjects or industries, these types of bibliographies play a vital role in facilitating the exploration, understanding, and dissemination of knowledge in diverse academic and intellectual domains.

As a discipline, a bibliography encompasses various types that cater to different research needs and contexts. The two main categories of bibliographies are

1. General bibliography, and 2. Special bibliography.

1.2.1. General Bibliography:

A general bibliography is a comprehensive compilation of sources covering a wide range of subjects, disciplines, and formats. It aims to provide a broad overview of published materials, encompassing books, articles, journals, websites, and other relevant resources. A general bibliography typically includes works from various authors, covering diverse topics and spanning different periods. It is a valuable tool for researchers, students, and readers seeking a comprehensive collection of literature within a specific field or across multiple disciplines. General bibliographies play a crucial role in guiding individuals in exploring a subject, facilitating the discovery of relevant sources, and establishing a foundation for further research and academic pursuits.

The general bibliography encompasses various subcategories that comprehensively cover global, linguistic, national, and regional sources. These subcategories are as follows:

- Universal Bibliography: Universal bibliography aims to compile a comprehensive list of all published works worldwide, regardless of subject or language. It seeks to encompass human knowledge and includes sources from diverse fields, cultures, and periods. Universal bibliography is a monumental effort to create a comprehensive record of the world’s published works, making it a valuable resource for scholars, librarians, and researchers interested in exploring the breadth of human intellectual output.

- Language Bibliography: Language bibliography focuses on compiling sources specific to a particular language or group of languages. It encompasses publications written in a specific language, regardless of the subject matter. Language bibliographies are essential for language scholars, linguists, and researchers interested in exploring the literature and resources available in a particular language or linguistic group.

- National Bibliography: The national bibliography documents and catalogs all published materials within a specific country. It serves as a comprehensive record of books, journals, periodicals, government publications, and other sources published within a nation’s borders. National bibliographies are essential for preserving a country’s cultural heritage, facilitating research within specific national contexts, and providing a comprehensive overview of a nation’s intellectual output.

- Regional Bibliography: A regional bibliography compiles sources specific to a particular geographic region or area. It aims to capture the literature, publications, and resources related to a specific region, such as a state, province, or local area. Regional bibliographies are valuable for researchers interested in exploring a specific geographic region’s literature, history, culture, and unique aspects.

1.2.2. Special Bibliography:

Special bibliography refers to a type of bibliography that focuses on specific subjects, themes, or niche areas within a broader field of study. It aims to provide a comprehensive and in-depth compilation of sources specifically relevant to the chosen topic. Special bibliographies are tailored to meet the research needs of scholars, researchers, and enthusiasts seeking specialized information and resources.

Special bibliographies can cover a wide range of subjects, including but not limited to specific disciplines, subfields, historical periods, geographical regions, industries, or even specific authors or works. They are designed to gather and present a curated selection of sources considered important, authoritative, or influential within the chosen subject area.

Special bibliography encompasses several subcategories that focus on specific subjects, authors, forms of literature, periods, categories of literature, and types of materials. These subcategories include:

- Subject Bibliography: Subject bibliography compiles sources related to a specific subject or topic. It aims to provide a comprehensive list of resources within a particular field. Subject bibliographies are valuable for researchers seeking in-depth information on a specific subject area, as they gather relevant sources and materials to facilitate focused research.

- Author and Bio-bibliographies: Author and bio-bibliographies focus on compiling sources specific to individual authors. They provide comprehensive lists of an author’s works, including their books, articles, essays, and other publications. Bio-bibliographies include biographical information about the author, such as their background, career, and contributions to their respective fields.

- Bibliography of Forms of Literature: This bibliography focuses on specific forms or genres of literature, such as poetry, drama, fiction, or non-fiction. It provides a compilation of works within a particular literary form, enabling researchers to explore the literature specific to their interests or to gain a comprehensive understanding of a particular genre.

- Bibliography of Materials of Particular Periods: Bibliographies of materials of particular periods compile sources specific to a particular historical period or time frame. They include works published or created during that period, offering valuable insights into the era’s literature, art, culture, and historical context.

- Bibliographies of Special Categories of Literature: This category compiles sources related to special categories or themes. Examples include bibliographies of children’s literature, feminist literature, postcolonial literature, or science fiction literature. These bibliographies cater to specific interests or perspectives within the broader field of literature.

- Bibliographies of Specific Types of Materials: Bibliographies of specific materials focus on compiling sources within a particular format or medium. Examples include bibliographies of manuscripts, rare books, visual art, films, or musical compositions. These bibliographies provide valuable resources for researchers interested in exploring a specific medium or format.

1.3 Functions of Bibliography

A bibliography serves several important functions in academic research, writing, and knowledge dissemination. Here are some key functions:

- Documentation: One of the primary functions of a bibliography is to document and record the sources consulted during the research process. By providing accurate and detailed citations for each source, it can ensure transparency, traceability, and accountability in scholarly work. It allows readers and other researchers to verify the information, trace the origins of ideas, and locate the original sources for further study.

- Attribution and Credit: The bibliography plays a crucial role in giving credit to the original authors and creators of the ideas, information, and materials used in research work. By citing the sources, the authors acknowledge the intellectual contributions of others and demonstrate academic integrity. This enables proper attribution and prevents plagiarism, ensuring ethical research practices and upholding the principles of academic honesty.

- Verification and Quality Control: It acts as a means of verification and quality control in academic research. Readers and reviewers can assess the information’s reliability, credibility, and accuracy by including a list of sources. This allows others to evaluate the strength of the evidence, assess the validity of the arguments, and determine the scholarly rigor of a work.

- Further Reading and Exploration: The bibliography is valuable for readers who wish to delve deeper into a particular subject or topic. By providing a list of cited sources, the bibliography offers a starting point for further reading and exploration. It guides readers to related works, seminal texts, and authoritative materials, facilitating their intellectual growth and expanding their knowledge base.

- Preservation of Knowledge: The bibliography contributes to the preservation of knowledge by cataloguing and documenting published works. It records the intellectual output within various fields, ensuring that valuable information is not lost over time. A bibliography facilitates the organization and accessibility of literature, making it possible to locate and retrieve sources for future reference and research.

- Intellectual Dialogue and Scholarship: The bibliography fosters intellectual dialogue and scholarship by facilitating the exchange of ideas and enabling researchers to build upon existing knowledge. By citing relevant sources, researchers enter into conversations with other scholars, engaging in a scholarly discourse that advances knowledge within their field of study.

A bibliography serves the important functions of documenting sources, crediting original authors, verifying information, guiding further reading, preserving knowledge, and fostering intellectual dialogue. It plays a crucial role in maintaining academic research’s integrity, transparency, and quality and ensures that scholarly work is built upon a solid foundation of evidence and ideas.

1.4 Importance of Bibliographic Services

Bibliographic services are crucial in academia, research, and information management. They are a fundamental tool for organizing, accessing, and preserving knowledge . From facilitating efficient research to ensuring the integrity and credibility of scholarly work, bibliographic services hold immense importance in various domains.

Bibliographic services are vital for researchers and scholars. These services provide comprehensive and reliable access to various resources, such as books, journals, articles, and other scholarly materials. By organizing these resources in a structured manner, bibliographic services make it easier for researchers to locate relevant information for their studies. Researchers can explore bibliographic databases, catalogues, and indexes to identify appropriate sources, saving them valuable time and effort. This accessibility enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of research, enabling scholars to stay up-to-date with the latest developments in their fields.

Bibliographic services also aid in the process of citation and referencing. Proper citation is an essential aspect of academic integrity and intellectual honesty. Bibliographic services assist researchers in accurately citing the sources they have used in their work, ensuring that credit is given where it is due. This not only acknowledges the original authors and their contributions but also strengthens the credibility and authenticity of the research. By providing citation guidelines, formatting styles, and citation management tools, bibliographic services simplify the citation process, making it more manageable for researchers.

Another crucial aspect of bibliographic services is their role in preserving and archiving knowledge. Libraries and institutions that provide bibliographic services serve as custodians of valuable information. They collect, organize, and preserve various physical and digital resources for future generations. This preservation ensures that knowledge is not lost or forgotten over time. Bibliographic services enable researchers, students, and the general public to access historical and scholarly materials, fostering continuous learning and intellectual growth.

Bibliographic services contribute to the dissemination of research and scholarly works. They provide platforms and databases for publishing and sharing academic outputs. By cataloguing and indexing research articles, journals, and conference proceedings, bibliographic services enhance the discoverability and visibility of scholarly work. This facilitates knowledge exchange, collaboration, and innovation within academic communities. Researchers can rely on bibliographic services to share their findings with a broader audience, fostering intellectual dialogue and advancing their respective fields.

In Summary, bibliographic services are immensely important in academia, research, and information management. They facilitate efficient analysis, aid in proper citation and referencing, preserve knowledge for future generations, and contribute to the dissemination of research. These services form the backbone of scholarly pursuits, enabling researchers, students, and professionals to access, utilize, and contribute to the vast wealth of knowledge available. As we continue to rely on information and research to drive progress and innovation, the significance of bibliographic services will only grow, making them indispensable resources in pursuing knowledge.

References:

- Reddy, P. V. G. (1999). Bio bibliography of the faculty in social sciences departments of Sri Krishnadevaraya university Anantapur A P India.

- Sharma, J.S. Fundamentals of Bibliography, New Delhi : S. Chand & Co.. Ltd.. 1977. p.5.

- Quoted in George Schneider, Theory of History of Bibliography. Ralph Robert Shaw, trans., New York : Scare Crow Press, 1934, p.13.

- Funk Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of the English language – International ed – Vol. I – New York : Funku Wagnalls Co., C 1965, p. 135.

- Shores, Louis. Basic reference sources. Chicago : American Library Association, 1954. p. 11-12.

- Ranganathan, S.R., Documentation and its facts. Bombay : Asia Publishing House. 1963. p.49.

- Katz, William A. Introduction to reference work. 4th ed. New York : McGraw Hill, 1982. V. 1, p.42.

- Robinson, A.M.L. Systematic Bibliography. Bombay : Asia Publishing House, 1966. p.12.

- Chakraborthi, M.L. Bibliography : In Theory and practice, Calcutta : The World press (P) Ltd.. 1975. p.343.

Related Posts

National bibliography, bibliographic services.

This site was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something which helped me. Thanks!

You really make it seem so easy along with your presentation but I find this topic to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It kind of feels too complex and very vast for me. I am having a look ahead in your next publish, I’ll try to get the grasp of it!

I’m Ghulam Murtaza

Thank for your detailed explanation,the work really help me to understand bibliography more than I knew it before.

thanks for this big one, and i get concept about bibliography( reference) that is great!!!!!

Leave A Reply Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Bibliography in APA Format

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

- APA Bibliography

- How to Create One

- Why You Need It

Sample Bibliography

An APA format bibliography lists all of the sources that might be used in a paper. A bibliography can be a great tool to help you keep track of information during the research and writing process. In some cases, your instructor may require you to include a bibliography as part of your assignment.

At a Glance

A well-written APA format bibliography can help you keep track of information and sources as you research and write your psychology paper. To create a bibliography, gather up all of the sources that you might use in your paper. Create an APA format reference for each source and then write a brief annotation. Your annotation should be a brief summary of what each reference is about. You can quickly refer to these annotations When writing your paper and determine which to include.

What Is an APA Format Bibliography?

An APA format bibliography is an alphabetical listing of all sources that might be used to write an academic paper, essay, article, or research paper—particularly work that is covering psychology or psychology-related topics. APA format is the official style of the American Psychological Association (APA). This format is used by many psychology professors, students, and researchers.

Even if it is not a required part of your assignment, writing a bibliography can help you keep track of your sources and make it much easier to create your final reference page in proper APA format.

Creating an APA Bibliography

A bibliography is similar in many ways to a reference section , but there are some important differences. While a reference section includes every source that was actually used in your paper, a bibliography may include sources that you considered using but may have dismissed because they were irrelevant or outdated.

Bibliographies can be a great way to keep track of information you might want to use in your paper and to organize the information that you find in different sources. The following are four steps you can follow to create your APA format bibliography.

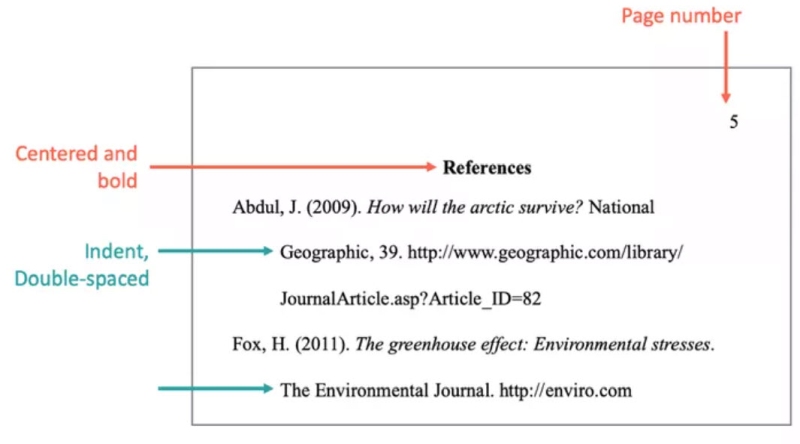

Start on a New Page

Your working bibliography should be kept separate from the rest of your paper. Start it on a new page, with the title "Bibliography" centered at the top and in bold text. Some people use the title "References" instead, so it's best to check with your professor or instructor about which they prefer you to use.

Gather Your Sources

Compile all the sources you might possibly use in your paper. While you might not use all of these sources in your paper, having a complete list will make it easier later on when you prepare your reference section.

Gathering your sources can be particularly helpful when outlining and writing your paper.

By quickly glancing through your working bibliography, you will be able to get a better idea of which sources will be the most appropriate to support your thesis and main points.

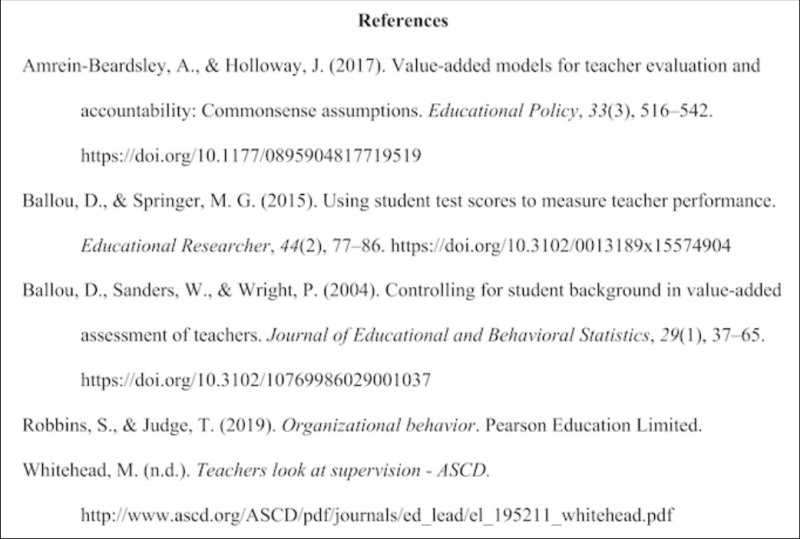

Reference Each Source

Your references should be listed alphabetically by the author’s last name, and they should be double-spaced. The first line of each reference should be flush left, while each additional line of a single reference should be a few spaces to the right of the left margin, which is known as a hanging indent.

The format of each source is as follows for academic journals:

- Last name of first author (followed by their first initial)

- The year the source was published in parentheses

- The title of the source

- The journal that published the source (in italics)

- The volume number, if applicable (in italics)

- The issue number, if applicable

- Page numbers (in parentheses)

- The URL or "doi" in lowercase letters followed by a colon and the doi number, if applicable

The following examples are scholarly articles in academic journals, cited in APA format:

- Kulacaoglu, F., & Kose, S. (2018). Borderline personality disorder (BPD): In the midst of vulnerability, chaos, and awe. Brain sciences , 8 (11), 201. doi:10.3390/brainsci8110201

- Cattane, N., Rossi, R., & Lanfredi, M. (2017). Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: exploring the affected biological systems and mechanisms. BMC Psychiatry, 18 (221). doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1383-2

Visit the American Psychological Association's website for more information on citing other types of sources including online media, audiovisual media, and more.

Create an Annotation for Each Source

Normally a bibliography contains only references' information, but in some cases you might decide to create an annotated bibliography. An annotation is a summary or evaluation of the source.

An annotation is a brief description of approximately 150 words describing the information in the source, your evaluation of its credibility, and how it pertains to your topic. Writing one of these for each piece of research will make your writing process faster and easier.

This step helpful in determining which sources to ultimately use in your paper. Your instructor may also require it as part of the assignment so they can assess your thought process and understanding of your topic.

Reasons to Write a Bibliography

One of the biggest reasons to create an APA format bibliography is simply to make the research and writing process easier.

If you do not have a comprehensive list of all of your references, you might find yourself scrambling to figure out where you found certain bits of information that you included in your paper.

A bibliography is also an important tool that your readers can use to access your sources.

While writing an annotated bibliography might not be required for your assignment, it can be a very useful step. The process of writing an annotation helps you learn more about your topic, develop a deeper understanding of the subject, and become better at evaluating various sources of information.

The following is an example of an APA format bibliography by the website EasyBib:

There are many online resources that demonstrate different formats of bibliographies, including the American Psychological Association website . Purdue University's Online Writing Lab also has examples of formatting an APA format bibliography.

Check out this video on their YouTube channel which provides detailed instructions on formatting an APA style bibliography in Microsoft Word.

You can check out the Purdue site for more information on writing an annotated APA bibliography as well.

What This Means For You

If you are taking a psychology class, you may be asked to create a bibliography as part of the research paper writing process. Even if your instructor does not expressly require a bibliography, creating one can be a helpful way to help structure your research and make the writing process more manageable.

For psychology majors , it can be helpful to save any bibliographies you have written throughout your studies so that you can refer back to them later when studying for exams or writing papers for other psychology courses.

American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 7th Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2020.

Masic I. The importance of proper citation of references in biomedical articles. Acta Inform Med . 2013;21(3):148–155. doi:10.5455/aim.2013.21.148-155

American Psychological Association. How do you format a bibliography in APA Style?

Cornell University Library. How to prepare an annotated bibliography: The annotated bibliography .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

- Harvard Style Bibliography | Format & Examples

Harvard Style Bibliography | Format & Examples

Published on 1 May 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 7 November 2022.

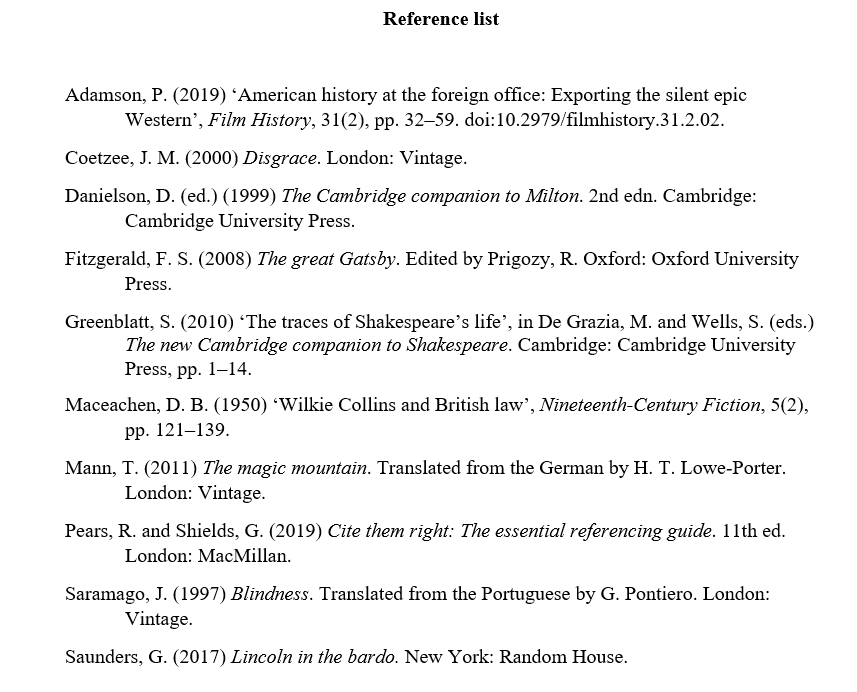

In Harvard style , the bibliography or reference list provides full references for the sources you used in your writing.

- A reference list consists of entries corresponding to your in-text citations .

- A bibliography sometimes also lists sources that you consulted for background research, but did not cite in your text.

The two terms are sometimes used interchangeably. If in doubt about which to include, check with your instructor or department.

The information you include in a reference varies depending on the type of source, but it usually includes the author, date, and title of the work, followed by details of where it was published. You can automatically generate accurate references using our free reference generator:

Harvard Reference Generator

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Formatting a harvard style bibliography, harvard reference examples, referencing sources with multiple authors, referencing sources with missing information, frequently asked questions about harvard bibliographies.

Sources are alphabetised by author last name. The heading ‘Reference list’ or ‘Bibliography’ appears at the top.

Each new source appears on a new line, and when an entry for a single source extends onto a second line, a hanging indent is used:

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Reference list or bibliography entries always start with the author’s last name and initial, the publication date and the title of the source. The other information required varies depending on the source type. Formats and examples for the most common source types are given below.

- Entire book

- Book chapter

- Translated book

- Edition of a book

Journal articles

- Print journal

- Online-only journal with DOI

- Online-only journal without DOI

- General web page

- Online article or blog

- Social media post

Newspapers and magazines

- Newspaper article

- Magazine article

When a source has up to three authors, list all of them in the order their names appear on the source. If there are four or more, give only the first name followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Sometimes a source won’t list all the information you need for your reference. Here’s what to do when you don’t know the publication date or author of a source.

Some online sources, as well as historical documents, may lack a clear publication date. In these cases, you can replace the date in the reference list entry with the words ‘no date’. With online sources, you still include an access date at the end:

When a source doesn’t list an author, you can often list a corporate source as an author instead, as with ‘Scribbr’ in the above example. When that’s not possible, begin the entry with the title instead of the author:

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a difference in meaning:

- A reference list only includes sources cited in the text – every entry corresponds to an in-text citation .

- A bibliography also includes other sources which were consulted during the research but not cited.

In Harvard referencing, up to three author names are included in an in-text citation or reference list entry. When there are four or more authors, include only the first, followed by ‘ et al. ’

In Harvard style referencing , to distinguish between two sources by the same author that were published in the same year, you add a different letter after the year for each source:

- (Smith, 2019a)

- (Smith, 2019b)

Add ‘a’ to the first one you cite, ‘b’ to the second, and so on. Do the same in your bibliography or reference list .

To create a hanging indent for your bibliography or reference list :

- Highlight all the entries

- Click on the arrow in the bottom-right corner of the ‘Paragraph’ tab in the top menu.

- In the pop-up window, under ‘Special’ in the ‘Indentation’ section, use the drop-down menu to select ‘Hanging’.

- Then close the window with ‘OK’.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, November 07). Harvard Style Bibliography | Format & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/referencing/harvard-bibliography/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, a quick guide to harvard referencing | citation examples, harvard in-text citation | a complete guide & examples, referencing books in harvard style | templates & examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

31 Bibliography

Annotated bibliography.

A bibliography is an alphabetized list of sources showing the author, date, and publication information for each source.

An annotation is like a note; it’s a brief paragraph that explains what the writer learned from the source.

Annotated bibliographies combine bibliographies and brief notes about the sources.

Writers often create annotated bibliographies as a part of a research project, as a means of recording their thoughts and deciding which sources to actually use to support the purpose of their research. Some writers include annotated bibliographies at the end of a research paper as a way of offering their insights about the source’s usability to their readers.

Instructors in college often assign annotated bibliographies as a means of helping students think through their source’s quality and appropriateness to their research question or topic. (23)

Formatting the Annotated Bibliography

The citations (bibliographic information – title, date, author, publisher, etc.) in the annotated bibliography are formatted using the particular style manual (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) that your discipline requires.

Annotations are written in paragraph form, usually 3-7 sentences (or 80-200 words). Depending on your assignment your annotations will generally include the following:

- Summary: Summarize the information given in the source. Note the intended audience. What are the main arguments? What is the point of this book or article? What topics are covered? If someone asked what this article/book is about, what would you say?

- Evaluate/Assess: Is this source credible? Who wrote it? What are their credentials? Who is the publisher? Is it a useful source? How does it compare with other sources in your bibliography? Is the information reliable? Is this source biased or objective? What is the goal of this source?

- Reflect/React: Once you’ve summarized and assessed a source, you need to ask how it fits into your research. State your reaction and any additional questions you have about the information in your source. Was this source helpful to you? How does it help you shape your argument? How can you use this source in your research project? Has it changed how you think about your topic? Compare each source to other sources in your annotated bibliography in terms of its usefulness and thoroughness in helping answer your research question. (24)

Annotated Bibliography Examples

In the following examples, the bold font indicates the reflection component of the annotation that is sometimes required in an assignment.

APA style 6 th edition for the journal citation:

Waite, L. J., Goldschneider, F. K., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review , 51, 541-554.

The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living. (25)

MLA 8 style for a website citation:

Anderson, L.V. “Can You Libel Someone on Twitter?” Slate.com, The Slate Group, A Graham Holdings. Company, 26 Nov. 2012, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/explainer/2012/11/libel_on_twitter_you_can_be_sued_for_libel_for_what_you_write_on_facebook.html . Accessed 2 Apr. 2018.

This article provides an overview of defamation law in the United States compared to the United Kingdom, in layman’s terms. It also explains how defamation law applies to social media platforms and individuals who use social media. Libelous comments posted on social media can be subject to lawsuit, depending on the content of the statement, and whether the person is a public or private figure. The article is found on the website, Slate.com, which is a web-based daily magazine that focuses on general interest topics. While the writer’s credentials are unavailable, she does thank Sandra S. Baron, Executive Director of the Media Law Resource Center and Jeff Hermes, director of the Digital Media Law Project for providing information. She also links to the United States laws that she cites. I would use the article to compare United States law to United Kingdom law and for background information. (1)

Information creation is a process. Scholars produce information in the forms of peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and conference presentations, to name a few. As a student researcher, you will be expected to create research projects such as essays, reports, visual presentations, and annotated bibliographies. Most scholarly writing makes an argument—whether it is to persuade your readers that your claim is true or to act on it. In order to create a sound argument, you must gather sources that will argue and counter-argue your claims.

When creating an argument, the researcher typically organizes their report or presentation with the claim/thesis at the beginning, which answers their research question. Then they provide reasons and supporting evidence to validate their claim. They acknowledge and respond to counter-arguments by citing sources that disagree with them, and refuting or conceding those counter-claims. Their conclusion restates their thesis and discusses why their research is important to the scholarly conversation, as well as potential areas for further research.

A Roman numeral outline is one way to organize your argument before you begin writing. It helps to identify sources for each section of your outline, so you know if you need further research to support your argument.

An annotated bibliography is one way to present research, and can be used as a cumulative assignment, or a precursor to your actual research paper. A good annotated bibliography will provide a variety of sources that met all your research needs—background, evidence, argument, and method. In other words, you should be able to take your annotated bibliography and write a complete research report based on those sources. (1)

Introduction to College Research Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing pp 657–665 Cite as

How to Create a Bibliography

- Rohan Reddy 4 ,

- Samuel Sorkhi 4 ,

- Saager Chawla 4 &

- Mahadevan Raj Rajasekaran 5

- First Online: 01 October 2023

568 Accesses

This chapter describes the fundamental principles and practices of referencing sources in scientific writing and publishing. Understanding plagiarism and improper referencing of the source material is paramount to producing original work that contains an authentic voice. Citing references helps authors to avoid plagiarism, give credit to the original author, and allow potential readers to refer to the legitimate sources and learn more information. Furthermore, quality references serve as an invaluable resource that can enlighten future research in a field. This chapter outlines fundamental aspects of referencing as well as how these sources are formatted as per recommended citation styles. Appropriate referencing is an important tool that can be utilized to develop the credibility of the author and the arguments presented. Additionally, online software can be useful in helping the author organize their sources and promote proper collaboration in scientific writing.

- Referencing

- Harvard and Vancouver styles

- Referencing software

- Scientific writing

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

AWELU (2022) The functions of references. Lund University. https://www.awelu.lu.se/referencing/the-functions-of-references/ . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Masic I (2013) The importance of proper citation of references in biomedical articles. Acta Inform Med 21(3):148–155

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Neville C (2012) Referencing: principles, practice and problems. RGUHS J Pharm Sci 2(2):1–8

Google Scholar

Horkoff T (2015) Writing for success 1st Canadian edition: BCcampus. Chapter 7. Sources: choosing the right ones. https://opentextbc.ca/writingforsuccess/chapter/chapter-7-sources-choosing-the-right-ones/ . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

A guide to database and catalog searching: bibliographic elements. Northwestern State University. https://libguides.nsula.edu/howtosearch/bibelements . Updated 5 Aug 2021; Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Research process: step 7: citing and keeping track of sources. University of Rio Grande. https://libguides.rio.edu/c.php?g=620382&p=4320145 . Updated 12 Dec 2022; Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Pears R, Shields G (2022) Cite them right. Bloomsbury Publishing

Harvard system (1999) Bournemouth University. http://ibse.hk/Harvard_System.pdf . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Gitanjali B (2004) Reference styles and common problems with referencing: Medknow. https://www.jpgmonline.com/documents/author/24/11_Gitanjali_3.pdf . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Williams K, Spiro J, Swarbrick N (2008) How to reference Harvard referencing for Westminster Institute students. Westminster Institute of Education Oxford Brookes University

Harvard: reference list and bibliography: University of Birmingham. 2022. https://intranet.birmingham.ac.uk/as/libraryservices/library/referencing/icite/harvard/referencelist.aspx . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Limited SN (2017) Responsible referencing. Nat Methods 14(3):209

Article Google Scholar

Hensley MK (2011) Citation management software: features and futures. Ref User Serv Q 50(3):204–208

Ramesh A, Rajasekaran MR (2014) Zotero: open-source bibliography management software. RGUHS J Pharm Sci 4:3–6

Shapland M (2000) Evaluation of reference management software on NT (comparing Papyrus with Procite, Reference Manager, Endnote, Citation, GetARef, Biblioscape, Library Master, Bibliographica, Scribe, Refs). University of Bristol

EndNote 20. Clarivate. 2022. https://endnote.com/product-details . Accessed 28 Dec 2022

Angélil-Carter S (2014) Stolen language? Plagiarism in writing. Routledge

Book Google Scholar

Howard RM (1995) Plagiarisms, authorships, and the academic death penalty. Coll Engl 57(7):788–806

Barrett R, Malcolm J (2006) Embedding plagiarism education in the assessment process. Int J Educ Integr 2(1):38–45

Introna L, Hayes N, Blair L, Wood E (2003) Cultural attitudes towards plagiarism. University of Lancaster, Lancaster, pp 1–57

Neville C (2016) The complete guide to referencing and avoiding plagiarism. McGraw-Hill Education (UK), London, p 43

Campion EW, Anderson KR, Drazen JM (2001) Internet-only publication. N Engl J Med 345(5):365

Li X, Crane N (1996) Electronic styles: a handbook for citing electronic information. Information Today, Inc.

APA (2005) Concise rules of APA style. APA, Washington, DC

Snyder PJ, Peterson A (2002) The referencing of internet web sites in medical and scientific publications. Brain Cogn 50(2):335–337

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barroga EF (2014) Reference accuracy: authors’, reviewers’, editors’, and publishers’ contributions. J Korean Med Sci 29(12):1587–1589

Standardization IOf (1997) Information and documentation—bibliographic references—part 2: electronic documents or parts thereof, ISO 690-2: 1997. ISO

Download references

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Urology, University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA

Rohan Reddy, Samuel Sorkhi & Saager Chawla

Department of Urology, University of California and VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA, USA

Mahadevan Raj Rajasekaran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mahadevan Raj Rajasekaran .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Retired Senior Expert Pharmacologist at the Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology, and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

Professor & Director, Research Training and Publications, The Office of Research and Development, Periyar Maniammai Institute of Science & Technology (Deemed to be University), Vallam, Tamil Nadu, India

Pitchai Balakumar

Division Cardiology & Nephrology, Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Fortunato Senatore

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Reddy, R., Sorkhi, S., Chawla, S., Rajasekaran, M.R. (2023). How to Create a Bibliography. In: Jagadeesh, G., Balakumar, P., Senatore, F. (eds) The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_39

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_39

Published : 01 October 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-1283-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-1284-1

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Citation Guide

- What is a Citation?

- Citation Generator

- Chicago/Turabian Style

- Paraphrasing and Quoting

- Examples of Plagiarism

What is a Bibliography?

What is an annotated bibliography, introduction to the annotated bibliography.

- Writing Center

- Writer's Reference Center

- Helpful Tutorials

- the authors' names

- the titles of the works

- the names and locations of the companies that published your copies of the sources

- the dates your copies were published

- the page numbers of your sources (if they are part of multi-source volumes)

Ok, so what's an Annotated Bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is the same as a bibliography with one important difference: in an annotated bibliography, the bibliographic information is followed by a brief description of the content, quality, and usefulness of the source. For more, see the section at the bottom of this page.

What are Footnotes?

Footnotes are notes placed at the bottom of a page. They cite references or comment on a designated part of the text above it. For example, say you want to add an interesting comment to a sentence you have written, but the comment is not directly related to the argument of your paragraph. In this case, you could add the symbol for a footnote. Then, at the bottom of the page you could reprint the symbol and insert your comment. Here is an example:

This is an illustration of a footnote. 1 The number “1” at the end of the previous sentence corresponds with the note below. See how it fits in the body of the text? 1 At the bottom of the page you can insert your comments about the sentence preceding the footnote.

When your reader comes across the footnote in the main text of your paper, he or she could look down at your comments right away, or else continue reading the paragraph and read your comments at the end. Because this makes it convenient for your reader, most citation styles require that you use either footnotes or endnotes in your paper. Some, however, allow you to make parenthetical references (author, date) in the body of your work.

Footnotes are not just for interesting comments, however. Sometimes they simply refer to relevant sources -- they let your reader know where certain material came from, or where they can look for other sources on the subject. To decide whether you should cite your sources in footnotes or in the body of your paper, you should ask your instructor or see our section on citation styles.

Where does the little footnote mark go?

Whenever possible, put the footnote at the end of a sentence, immediately following the period or whatever punctuation mark completes that sentence. Skip two spaces after the footnote before you begin the next sentence. If you must include the footnote in the middle of a sentence for the sake of clarity, or because the sentence has more than one footnote (try to avoid this!), try to put it at the end of the most relevant phrase, after a comma or other punctuation mark. Otherwise, put it right at the end of the most relevant word. If the footnote is not at the end of a sentence, skip only one space after it.

What's the difference between Footnotes and Endnotes?

The only real difference is placement -- footnotes appear at the bottom of the relevant page, while endnotes all appear at the end of your document. If you want your reader to read your notes right away, footnotes are more likely to get your reader's attention. Endnotes, on the other hand, are less intrusive and will not interrupt the flow of your paper.

If I cite sources in the Footnotes (or Endnotes), how's that different from a Bibliography?

Sometimes you may be asked to include these -- especially if you have used a parenthetical style of citation. A "works cited" page is a list of all the works from which you have borrowed material. Your reader may find this more convenient than footnotes or endnotes because he or she will not have to wade through all of the comments and other information in order to see the sources from which you drew your material. A "works consulted" page is a complement to a "works cited" page, listing all of the works you used, whether they were useful or not.

Isn't a "works consulted" page the same as a "bibliography," then?

Well, yes. The title is different because "works consulted" pages are meant to complement "works cited" pages, and bibliographies may list other relevant sources in addition to those mentioned in footnotes or endnotes. Choosing to title your bibliography "Works Consulted" or "Selected Bibliography" may help specify the relevance of the sources listed.

This information has been freely provided by plagiarism.org and can be reproduced without the need to obtain any further permission as long as the URL of the original article/information is cited.

How Do I Cite Sources? (n.d.) Retrieved October 19, 2009, from http://www.plagiarism.org/plag_article_how_do_i_cite_sources.html

The Importance of an Annotated Bibliography

An Annotated Bibliography is a collection of annotated citations. These annotations contain your executive notes on a source. Use the annotated bibliography to help remind you of later of the important parts of an article or book. Putting the effort into making good notes will pay dividends when it comes to writing a paper!

Good Summary

Being an executive summary, the annotated citation should be fairly brief, usually no more than one page, double spaced.

- Focus on summarizing the source in your own words.

- Avoid direct quotations from the source, at least those longer than a few words. However, if you do quote, remember to use quotation marks. You don't want to forget later on what is your own summary and what is a direct quotation!

- If an author uses a particular term or phrase that is important to the article, use that phrase within quotation marks. Remember that whenever you quote, you must explain the meaning and context of the quoted word or text.

Common Elements of an Annotated Citation

- Summary of an Article or Book's thesis or most important points (Usually two to four sentences)

- Summary of a source's methodological approach. That is, what is the source? How does it go about proving its point(s)? Is it mostly opinion based? If it is a scholarly source, describe the research method (study, etc.) that the author used. (Usually two to five sentences)

- Your own notes and observations on the source beyond the summary. Include your initial analysis here. For example, how will you use this source? Perhaps you would write something like, "I will use this source to support my point about . . . "

- Formatting Annotated Bibliographies This guide from Purdue OWL provides examples of an annotated citation in MLA and APA formats.

- << Previous: Examples of Plagiarism

- Next: ACM Style >>

- Last Updated: Feb 5, 2024 12:30 PM

- URL: https://libguides.limestone.edu/citation

What Is a Bibliography?

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A bibliography is a list of books, scholarly articles , speeches, private records, diaries, interviews, laws, letters, websites, and other sources you use when researching a topic and writing a paper. The bibliography appears at the end.

The main purpose of a bibliography entry is to give credit to authors whose work you've consulted in your research. It also makes it easy for a reader to find out more about your topic by delving into the research that you used to write your paper. In the academic world, papers aren't written in a vacuum; academic journals are the way new research on a topic circulates and previous work is built upon.

Bibliography entries must be written in a very specific format, but that format will depend on the particular style of writing you follow. Your teacher or publisher will tell you which style to use, and for most academic papers it will be either MLA , American Psychological Association (APA), Chicago (author-date citations or footnotes/endnotes format), or Turabian style .

The bibliography is sometimes also called the references, works cited, or works consulted page.

Components of a Bibliography Entry

Bibliography entries will compile:

- Authors and/or editors (and translator, if applicable)

- Title of your source (as well as edition, volume, and the book title if your source is a chapter or article in a multi-author book with an editor)

- Publication information (the city, state, name of the publisher, date published, page numbers consulted, and URL or DOI, if applicable)

- Access date, in the case of online sources (check with the style guide at the beginning of your research as to whether you need to track this information)

Order and Formatting

Your entries should be listed in alphabetical order by the last name of the first author. If you are using two publications that are written by the same author, the order and format will depend on the style guide.

In MLA, Chicago, and Turabian style, you should list the duplicate-author entries in alphabetical order according to the title of the work. The author's name is written as normal for his or her first entry, but for the second entry, you will replace the author's name with three long dashes.

In APA style, you list the duplicate-author entries in chronological order of publication, placing the earliest first. The name of the author is used for all entries.

For works with more than one author, styles vary as to whether you invert the name of any authors after the first. Whether you use title casing or sentence-style casing on titles of sources, and whether you separate elements with commas or periods also varies among different style guides. Consult the guide's manual for more detailed information.

Bibliography entries are usually formatted using a hanging indent. This means that the first line of each citation is not indented, but subsequent lines of each citation are indented. Check with your instructor or publication to see if this format is required, and look up information in your word processor's help program if you do not know how to create a hanging indent with it.

Chicago's Bibliography vs. Reference System

Chicago has two different ways of citing works consulted: using a bibliography or a references page. Use of a bibliography or a references page depends on whether you're using author-date parenthetical citations in the paper or footnotes/endnotes. If you're using parenthetical citations, then you'll follow the references page formatting. If you're using footnotes or endnotes, you'll use a bibliography. The difference in the formatting of entries between the two systems is the location of the date of the cited publication. In a bibliography, it goes at the end of an entry. In a references list in the author-date style, it goes right after the author's name, similar to APA style.

- What Is a Citation?

- What Is a Senior Thesis?

- Bibliography: Definition and Examples

- Formatting Papers in Chicago Style

- Turabian Style Guide With Examples

- MLA Bibliography or Works Cited

- How to Write a Bibliography For a Science Fair Project

- APA In-Text Citations

- MLA Sample Pages

- How to Use Block Quotations in Writing

- Writing a History Book Review

- Definition of Appendix in a Book or Written Work

- MLA Style Parenthetical Citations

- Tips for Typing an Academic Paper on a Computer

- Title Page Examples and Formats

- Formatting APA Headings and Subheadings

University Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Bibliography and Historical Research

Introduction.

- National Bibliography

- Personal Bibliography

- Corporate Bibliography

- Subject Bibliography

- Searching the Catalog for Bibliographies

- Browsing the Catalog for Bibliographies

- Other Tools for Finding Bibliographies

- Return to HPNL Website

Ask a Librarian

This guide created by Geoffrey Ross, May 4, 2017.

A bibliography is a list of documents, usually published documents like books and articles. This type of bibliography is more accurately called "enumerative bibliography". An enumerative bibliography will attempt to be as comprehensive as possible, within whatever parameters established by the bibliographer.

Bibliographies will list both secondary and primary sources. They are perhaps most valuable to historians for identifying primary sources. (They are still useful for finding secondary sources, but increasingly historians rely on electronic resources, like article databases, to locate secondary sources.)

Think of a bibliography as a guide to the source base for a specific field of inquiry. A high quality bibliography will help you understand what kinds of sources are available, but also what kinds of sources are not available (either because they were never preserved, or because they were never created in the first place).

Take for example the following bibliography:

- British Autobiographies: An Annotated Bibliography of British Autobiographies Published or Written before 1951 by William Matthews Call Number: 016.920041 M43BR Publication Date: 1955

Like many bibliographies, this one includes an introduction or prefatory essay that gives a bibliographic overview of the topic. If you were hoping to use autobiographies for a paper on medieval history, the following information from the preface would save you from wasting your time in a fruitless search:

The essay explains that autobiography does not become an important historical source until the early modern period:

Finally, the essay informs us that these early modern autobiographies are predominantly religious in nature--a useful piece of information if we were hoping to use them as evidence of, for example, the early modern textile trade:

All bibliographies are organized differently, but the best include indexes that help you pinpoint the most relevant entries.

A smart researcher will also use the index to obtain an overview of the entire source base: the index as a whole presents a broad outline of the available sources--the extent of available sources, as well as the the strengths and weaknesses of the source base. Browsing the subject index, if there is one, is often an excellent method of choosing a research topic because it enables you quickly to rule out topics that cannot be researched due to lack of primary sources.

The index to British Autobiographies , for example, tells me that I can find many autobiographies that document British social clubs (like White's and Boodle's), especially from the 19th century:

Unlike indexes you might be familiar with from non-fiction books, the indexes in bibliographies usually reference specific entries, not page numbers.

A bibliography's index will often help guide you systematically through the available sources, as in this entry which prompts you to look under related index entries for even more sources:

There are four main types of enumerative bibliography used for historical research:

Click here to learn more about bibliography as a discipline .

- Next: National Bibliography >>

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2023 2:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/bibliography

Research Process: Bibliographic Information

- Selecting a Topic

- Background Information

- Narrowing the Topic

- Library Terms

- Generating Keywords

- Boolean Operators

- Search Engine Strategies

- Google Searching

- Basic Internet Terms

- Research & The Web

- Search Engines

- Evaluating Books

- Evaluating Articles

- Evaluating Websites

Bibliographic Information

- Off Campus Access

- Periodical Locator

What is a bibliography?

A bibliography is a list of works on a subject or by an author that were used or consulted to write a research paper, book or article. It can also be referred to as a list of works cited. It is usually found at the end of a book, article or research paper.

Gathering Information

Regardless of what citation style is being used, there are key pieces of information that need to be collected in order to create the citation.

For books and/or journals:

- Author name

- Title of publication

- Article title (if using a journal)

- Date of publication

- Place of publication

- Volume number of a journal, magazine or encyclopedia

- Page number(s)

For websites:

- Author and/or editor name

- Title of the website

- Company or organization that owns or posts to the website

- URL (website address)

- Date of access

This section provides two examples of the most common cited sources: a print book and an online journal retrieved from a research database.

Book - Print

For print books, bibliographic information can be found on the TITLE PAGE . This page has the complete title of the book, author(s) and publication information.

The publisher information will vary according to the publisher - sometimes this page will include the name of the publisher, the place of publication and the date.

For this example : Book title: HTML, XHTML, and CSS Bible Author: Steven M. Schafer Publisher: Wiley Publications, Inc.

If you cannot find the place or date of publication on the title page, refer to the COPYRIGHT PAGE for this information. The copyright page is the page behind the title page, usually written in a small font, it carries the copyright notice, edition information, publication information, printing history, cataloging data, and the ISBN number.

For this example : Place of publication: Indianapolis, IN Date of publication: 2010

Article - Academic OneFile Database

In the article view:

Bibliographic information can be found under the article title, at the top of the page. The information provided in this area is NOT formatted according to any style.

Citations can also be found at the bottom of the page; in an area titled SOURCE CITATION . The database does not specify which style is used in creating this citation, so be sure to double check it against the style rules for accuracy.

Article - ProQuest Database

Bibliographic information can be found under the article title, at the top of the page. The information provided in this area is NOT formatted according to any style.

Bibliographic information can also be found at the bottom of the page; in an area titled INDEXING . (Not all the information provided in this area is necessary for creating citations, refer to the rules of the style being used for what information is needed.)

Other databases have similar formats - look for bibliographic information under the article titles and below the article body, towards the bottom of the page.

- << Previous: Plagiarism

- Next: Research Databases >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://pgcc.libguides.com/researchprocess

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

Academic integrity and documentation, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Types of Documentation

Bibliographies and Source Lists

What is a bibliography.

A bibliography is a list of books and other source material that you have used in preparing a research paper. Sometimes these lists will include works that you consulted but did not cite specifically in your assignment. Consult the style guide required for your assignment to determine the specific title of your bibliography page as well as how to cite each source type. Bibliographies are usually placed at the end of your research paper.

What is an annotated bibliography?

A special kind of bibliography, the annotated bibliography, is often used to direct your readers to other books and resources on your topic. An instructor may ask you to prepare an annotated bibliography to help you narrow down a topic for your research assignment. Such bibliographies offer a few lines of information, typically 150-300 words, summarizing the content of the resource after the bibliographic entry.

Example of Annotated Bibliographic Entry in MLA Style