carnaticstudent.org

for students and lovers of Carnatic music

A brief introduction to Carnatic music

Whatever one’s personal background and aspirations may be, Carnatic music remains a quest for undiluted aesthetic experience ( rasa ). 1 Three basic concepts are essential for daily practice as well as proper appreciation: rāga ( tuneful rendition with minute intervals and rich in embellishments ), tāla ( rhythmic order marked by mathematical precision ), and bhāva ( expression of thoughts and emotions ).

To appreciate how these qualities are being inculcated, listen to the very first song taught for generations and from a very young age – long before a learner grasps the other concepts that distinguish “classical” Carnatic music from its popular counterparts (devotional, folk and film music):

The origins of South Indian music are traced to prehistoric times. Musical instruments form a favorite subject for sculptors, painters and the authors of ancient Tamil and Sanskrit texts. Vocal and instrumental genres have have since coalesced into a single body of compositions and themes. These form the basis for creative elaboration and self-expression.

Several strands have been intertwining throughout Indian music history. The celebrated Kannada writer and dramatist, Kota Shivarama Karanth, went so far as to declare that Indian culture today is so varied as to be called ‘cultures’. 2

Music was cultivated by nobility and common people alike. A mere glance at India’s literary heritage, including poetry, drama, mythology and scholarly texts, reveals an ongoing quest for new ideas. The same can be said of performers, instrument makers and skilled amateurs. The resulting “art music” is in fact an amalgam of different “ regional” or “ indigenous” styles ( dēsi ). Today it is being studied all over the world on account of its continuity, infinite variety and a rare capacity for self-rejuvenation. 3

Carnatic music owes its name to the Sanskrit term Karnātaka Sangītam which denotes “traditional” or “codified” music. The corresponding Tamil concept is known as Tamil Isai. These terms are used by scholars upholding the “classical” credentials and establish the “scientific” moorings of traditional music. Besides Sanskrit and Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam have long been used for song lyrics.

Tips for using the interactive Carnaticstudent-map >>

Purandara Dāsa (1484-1564) 4 , a prolific poet-composer and mystic of Vijayanagar, introduced a music course that is followed to the present day. Since the 17th century, hundreds of rāga -s (melody types) have been distributed among the 72 melakarta rāgas (scales).

The type of song prevailing today, known as kriti (lit. “ creation “ ), was popularized by the most revered poet-composer of South India, Tyāgarāja (1767-1847), his contemporaries Syāma Sāstri and Muttusvāmi Dīkshitar (together known as the “Trinity” of Carnatic music), and their disciples.

Their songs built on the kīrtana tradition – lilting, easy to remember tunes suited for the congregational singing of South and North Indian lyrics just as those of Bengal 6

Comprising two or three melodic themes ( pallavi, anupallavi and charanam ), these songs continue to kindle creativity, even displays of virtuosity, among today’s singers and instrumentalists.

The modern-day kutcheri concert format emerged as late as the 20th century and is still widely followed today, in spite of much debated challenges by contemporary musicians like T.M. Krishna who seeks to “remove the barriers imposed by the music” through both, his concerts and in writing . 7

A performer may draw inspiration from sacred texts and epics, mythology, aphorisms, patriotic poetry, stories, customs such as festivals, and dances associated with a particular place of pilgrimage or centre of learning; and conclude with “light” songs such as lullabies and love poetry ( tukkada items). 8

Mangalamapalli Balamuralikrishna – one of the most revered singer-composers of Carnatic music of all times – reminded his students and listeners time and again that tradition without innovation has no meaning. “His daring efforts to tread unchartered territories in music and to look at music as a whole being larger than the mere sum of parts are also his strengths.” ( The Hindu, 30 July 2015 )

Text: Ludwig Pesch >>

Tip This website offers many resources for free (see menu for details): to learn more about the above mentioned composers and scholars, the places where they flourished; and about the musicians who tread in their footsteps today. Enjoy your exploration of a wonderful music!

By Rama Kausalya

The Tambura is considered queen among the Sruti vadhyas such as Ektar, Dotar, Tuntina, Ottu and Donai. Although tamburas are traditionally made at several places, the Thanjavur Tambura has a special charm.

Veena Asaris are the Tambura makers too but not all are experts, the reason being it requires a special skill to make the convex ‘Meppalagai’ or the plate covering the ‘Kudam’ (Paanai).

There are two ways of holding a Tambura. One is the “Urdhva” – upright posture, as in concerts. Placing the Tambura on the right thigh is the general practice. The other is to place it on the floor in front of the person who is strumming it. While practising or singing casually, it can be placed horizontally on the lap.

The middle finger and index finger are used to strum the Tambura. Of the four strings, the ‘Panchamam’, which is at the farther end is plucked by the middle finger followed by the successive plucking of ‘Sārani’, ‘Anusārani’ and ‘Mandara’ strings one after the other by the index finger. This exercise is repeated in a loop resulting in the reverberating sruti.

Sit in a quiet place with eyes closed and listen to the sa-pa-sa notes of a perfectly tuned Tambura – the effect is therapeutic.

Except a few, the current generation prefers electronic sruti accompaniment, portability being the obvious reason. Besides few music students are taught to tune and play the tambura. Beyond all this what seems to swing the vote is that the electronic sruti equipment with its heavy tonal quality can cover up when the sruti goes astray.

During the middle of the last century, Miraj Tambura (next only to the vintage Thanjavur) was a rage among music students, who were captivated by its tonal quality with high precision and the beautiful, natural gourd resonators.

Source: “Therapeutic effect”, The Hindu (Friday Review), 30 March 2018

Learn & practice more

- A brief introduction to Carnatic music (with music examples and interactive map)

- Bhava and Rasa explained by V. Premalatha

- Free “flow” exercises on this website

- Glossary (PDF)

- Introduction (values in the light of modernity)

- PDF-Repository

- Video | Keeping tala with hand gestures: Adi (8 beats) & Misra chapu (7 beats)

- Voice culture and singing

- Why Carnatic Music Matters More Than Ever

- Worldcat.org book and journal search (including Open Access)

- “Bharata mentions eight dominant emotional moods, or sthāyibāva-s, that may be aroused by a dramatic representation into the state of aesthetic pleasure. These are rati (love), hāsa (laughter), śōka (sorrow), krōdha (anger), utsāha (energy), bhaya (fear), jugupsā (repugnance) and vismaya (wonder); the rasa-s corresponding to these are respectively called śṛṅgāra, hāsya, karuṇa, raudra, vīra, bhayānaka, bībatsa and adbhuta. Later writers accept a nineth rasa called śānta corresponding to the sthāyibāva of nirvēda (detachment).” – Dr. V. Premalatha | Learn more >> [ ↩ ]

- Quoted by historian Ramachandra Guha in “Melody within” – Politics and Play: India’s classical music may be the best antidote to chauvinism” ( The Telegraph, 6 June 2020 ) [ ↩ ]

- For details, see Unity in Diversity, Antiquity in Contemporary Practice? South Indian Music Reconsidered (Goettingen University Press, Open Access), an essay by Ludwig Pesch [ ↩ ]

- A highly readable overview of various social and historical factors that distinguish Carnatic music is provided in the chapter titled “Songs from the soul: 1805–1847” in Modern South India: A History from the 17th Century to our Times by Rajmohan Gandhi , pp. 151-3 [ ↩ ]

- For clear translations of this composer’s lyrics, see Tyagaraja: Life and Lyrics by William J. Jackson , OUP Madras 1991 (for Entaro mahanubhavulu, see p. 210) [ ↩ ]

- According to Reba Som, Rabindranath Tagore (who didn’t know how to write music) “was often attracted by the distinctive styles of regional music [and] wrote about the great evocative power of tunes wafting across distances–carrying the message of an unknown address whispered in the ear by a traveller–bringing a note of hope and encouragement across oceans of divide.” Among these regional styles was Carnatic music with which he became acquainted “during his stay with civil servant brother Satyendranath in Karwar in western India”, an interest sustained during his 1919 visit to Madras where “he had heard with pleasure instrumental recitals on the veena in the south Indian style”. Reba Som, Rabindranath Tagore: The Singer and His Song , New Delhi: Penguin 2009 [ ↩ ]

- This is, for instance, evident in a review of his book, A Southern music , by Deepa Ganesh: “It is not easy to be T.M. Krishna. He will raise questions, challenge existing notions, unmindful of what the consequences will be” ( The Hindu, 20 March 2014 ) [ ↩ ]

- “Outside drama, there were other situations when rāga was associated with kāla. These were the temple rituals and social functions. In a temple, the Āgamic texts prescribe rituals which had to be performed during different parts of the day. Invariably with every ritual, there was performance of music, in the form of singing or playing the Nāgasvara and for each part of the day, a particular rāga or some rāga-s were prescribed. In social functions like marriages too, specific rāga-s are prescribed to be played on the nāgasvara during early morning and other times of the day.” – V. Premalatha (Central University of Tamil Nadu, Thiruvarur) in “ Association of Rasa and Kāla (time) with Rāga-s ” [ ↩ ]

- Darbar Player

- Concert Hall

- Start free trial

- Darbar Festival 2024

- Guru Nanak's Music

- Darbar Academy

In-depth Carnatic Primer: South India’s mellifluous, mathematical music

- Author: George Howlett

Carnatic music's wealth of powerful, highly developed ideas deserves far more global attention. Here's an in-depth South Indian primer.

—Part of Living Traditions : 21 articles for 21st-century Indian classical music

What is Carnatic music?

The Carnatic tradition is often explained to outsiders in terms of how it differs from Hindustani music, its better-known Northern equivalent. But while the styles share deep stylistic roots, Carnatic music deserves a distinct mode of listening. In this article we sample the sounds and ideas of South Indian classical, and trace its evolution through the lives of great masters past and present.

Where better to start than with the music itself? Watch Aruna Sairam lead a 5-piece Carnatic group through Kalinga Nartana Thillana , live from Darbar 2016. Based on poetry from the 6th century, the composition recounts Lord Krishna’s mythical battle with Kaliya, a fearsome five-headed snake who boiled the waters of the Yamuna River around them as they fought. Aruna uses rhythmic vocalisations to depict Krishna’s battle dances, timing each syllable to perfection and even hissing in imitation of the serpent:

The piece showcases many of Carnatic music’s distinctive characteristics. It tends to be performed in small groups, usually led by a vocalist, who receives melodic support from one or more string instruments (in this case a violin and veena ). Rhythm comes from a selection of hand drums (here a mridangam and ghatam clay pot). A tanpura emits a steady background drone, anchoring the other sounds.

The music focuses on song compositions. Melody reigns supreme - musicians learn their art by internalising thousands of them, building up a vast shared vocabulary. Lyrics, often in Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, or Sanskrit, usually depict scenes of divinity and devotion. Words are vital, and even instrumentalists tend to study the lyrical meaning of songs they play.

The tradition’s huge bank of melodic material serves as the fuel for extended solo improvisation, known as kalpana sangeetham ('music of the imagination'). Certain sections of a performance allow the soloist to stretch out and explore the full emotional space of the ragam (also spelt raga ). There are hundreds of Carnatic ragam to choose from, each containing unique melodic instructions (more on ragam theory later).

Despite its complexities, South India’s classical music is not difficult to listen to. It need not be understood to be enjoyed - all you require is an open mind and a willingness to hear the sounds on their own terms. And while the roots of Carnatic music are ancient, we should never forget that it is a living tradition, spontaneously updating itself as each moment of a performance unfurls. Like all improvised music, it is best experienced live.

Kutcheri : what happens at a Carnatic concert?

So if you do go to a Carnatic concert, what can you expect? Known as a kutcheri , a classical performance usually lasts for two to three hours. Attendees may encounter a selection of different sub-genres:

• Kritis - elaborate pre-composed songs - are at the heart of Carnatic music. A kriti (‘creation’) traditionally comes in three parts. First is the pallavi (a Sanskrit word meaning ‘tender, red-coloured leaves’), a thematic chorus-type line. Then comes the anupallavi (‘small pallavi’), developing the original melody. Finally, the charanam (‘foot’) concludes the kriti .

• The ragam-tanam-pallavi has a central place in many instrumental concerts. Another three-part form, it gives great room for improvisation, allowing artists to explore the full identity of the chosen ragam . A rhythmless introduction known as alapana (‘discourse’) introduces the notes gradually, and is followed by a tanam - a gently pulsed expansion of the raga based on syllables from the phrase ‘ Ananta Anandam Ta ’ (‘Oh Lord, give me happiness’). The final section starts with a thematic pallavi line, which is then used as the launching pad for improvisation.

• The varnam (‘colour’) is a lively song form, where a basic refrain is run through all manner of intricate permutations. Artists turn the refrain’s quick familiarity on its head, twisting and reshaping it to bring out a hidden wealth of new sentiments. Varnams are usually sung before the kriti , warming up the audience and helping set the tones of the main ragam .

• The tani avartanam has gained greater popularity over the last few generations, often finding space in the latter stages of a ragam-tanam-pallavi . The exclusive realm of the drummers, it is usually a group effort featuring all percussionists on stage. They pass dense phrases between each other, stretching their ideas through different time cycles and captivating the crowd with virtuosic feats of collaborative competition.

• A thillana is a rhythmic song, often played or sung as the last item of the kutcheri . Strongly tied to Indian classical dance forms, its strong, driving rhythms bring a sense of release, providing a satisfying conclusion to the evening. Some consider the thillana to derive from the North Indian tarana , a fast-paced style influenced by Persian and Arabic music.

There are many more, including various folk-derived tunes and an unclassifiable plethora of mixed forms, sometimes inspired by recent contact with other cultures. Some of these will turn up as we explore further.

• Listen | Jyotsna Srikanth heard Carnatic violin for the first time at the age of five. Soon after, her mother came home to find her imitating the instrument by scraping two broomsticks together (“I was desperate to hear that sound again...”). She learnt it with gurus including RR Keshavamurthy, the legendary seven-string violinist of Karnataka. After several years as a medical doctor she moved to London and took up music full-time, and is now a mainstay of Europe’s global music circuit. Here she plays an alapana (rhythmless introduction) in Raga Keeravani:

A brief history of Carnatic music

All Indian classical music is spiritual and devotional in origin. In the words of Carnatic musicologist Dr. V Raghavan, “The arts are aids for communion with God or self...they help to sublimate the human emotions by giving them a divine object...[and] in the experience of the beauty and the bliss engendered thereby, they give a glimpse, a taste of the ineffable repose that belongs enduringly to the summum bonum [highest good]”.

Such sentiments go back a long way. Yajnavalkya, a sage from the 8th century BCE, saw music as the most direct path to salvation: "Contemplate on one's self, shining like a lamp within oneself. By singing the samans in the proper manner, without interruption and with concentration, one attains by practice the Supreme Being”. The samans he refers to are songs taken from the Samaveda, a Sanskrit work from around 3,000 years ago that sets hundreds of Vedic hymns to what is thought to be the world’s oldest known system of melodic notation.

Early devotional songs such as this formed a vital part of South Indian temple life. Instruments also began to find their place, with Vedic yajna (fire rituals) often being accompanied by ancestors of the veena and mridangam . The music grew into a sophisticated, well-codified body of knowledge by the year zero AD, and became coloured by many shades of folk influence over the next few centuries.

India’s classical music has not always been divided into Northern and Southern variants. The process of bifurcation seems to have started some time between the 13th and 15th centurie - musicological treatises from the former period make no mention of it, but the work of Kallintha in the latter refers to a style called Karnataka Sangeeta , existing only between South India’s Kaveri and Krishna rivers. Much of the overall branching was due to the injection of Islamic ideas into North Indian music, which did not exert such a political or social pull on South India (although the South did fall under Mughal control at times).

The 16th century brought some of the music’s most significant developments. Purandara Dasa grew up in a wealthy family, following in his father’s footsteps by becoming a successful diamond trader. But aged 30 he renounced his material riches and became a Haridasa , wandering from town to town and singing praise to Lord Krishna. Over the rest of his life he brought the music to thousands, introducing new song forms and writing melodic exercises that are still used by modern students.

The bulk of today’s vocal repertoire was written by three outstanding composers of the late 18th and early 19th century - Tyagaraja, Shyama Shastri, and Muthuswami Dikshitar. Known as the Trimurti (Trinity), they were all born within a few years of each other in the Tamil Nadu town of Thiruvarur. All three died before 1850, but their work continues to dominate much of the Carnatic landscape.

Shyama Shastri , the eldest, is notable for adapting ideas from dance-based music, setting them to a variety of complex ragam and talam and composing influential kritis in the Telugu language. Muthuswami Dikshitar looked further afield, drawing on North Indian vocal techniques and even composing a 39-piece suite inspired by Scottish and Irish folk tunes brought over by employees of the British East India company (the Nottuswara ).

Tyagaraja (above), the most influential of the trio, was a lifelong devotee of the Lord Rama. His music reflects these spiritual inclinations while also depicting scenes from everyday life, combining the celestial with the mundane. Known for focusing on emotion rather than virtuosity, he is fabled to have composed around 25,000 songs, although 'only' around 700 survive today. The best known of these are the Pancharatna (‘five jewels’), a set of kritis famed for their mellifluous, concise exposition of complex musical and spiritual ideas.

Like many Carnatic composers, the Trimurti often 'signed off' their works with a mudra , the technique of subtly working the syllables of one's own name (or pseudonym) into the final line of the lyrics (something that has an oddly hip-hop vibe). Shastri went by the mudra 'Shyama Krishna', and Dikshitar by 'Guruguha', both borrowing the names of Hindu gods they identified with, while 'Tyagaraja' is already a divinely-inspired nickname of sorts - he was born Kakarla Tyagabrahmam, taking his more famous identifier in honour of Lord Shiva.

The late 19th century saw a plethora of further innovations. Naraynaswami Appa and Manpoondia Pillai developed the art of mridangam playing, founding the Tanjore and Pudukkottai traditions respectively. The steady rise of the composer-performer raised technical standards, and written notation began to find a greater role in what had been a predominantly aural tradition.

These trends continued into the 20th century. Vocal legends led the way - including MS Subbulakshmi, the ‘Nightingale of India’, and another trinity of male singers - Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, GN Balasubramaniam, and Madurai Mani Iyer.

Carnatic music, historically speaking, has tended towards social tolerance, cutting across lines of caste and religion. But the anti-nautch movement of the early 20th century saw a more puritanical turn, as upper-class campaigners pushed to outlaw the devadasis - ‘women of the temple’ who sang, danced, and assisted with the performance of rituals.

Their role could also involve prostitution, angering those who wished to “orient all females in the service of the home and nation”. Waves of legal bans greatly diminished the tradition's prevalence, stigmatising the music by association. Despite admirable preservation efforts, countless song and dance forms were lost, particularly those steeped in eroticism rather than religious piety. Many see this period as a turning point, with the music becoming increasingly confined to upper-caste Brahmin families from then on (more on this later).

Recent generations have seen Carnatic ideas reach a wide domestic audience. However much of this has come through the success of South Indian singers on the filmi platform, while the cultural reach of traditional performance has dwindled. But the music itself has remained strong, upheld by a dedicated core of devotees. The Chennai (formerly Madras) Music Season continues to attract vast crowds, packing thousands of classical concerts into a fortnight each year.

Carnatic vocals

All India’s main classical traditions see vocal music as the pinnacle of their art, revering its direct, primal essence. But Carnatic’s particular focus on song composition gives the human voice an even greater importance, meaning singers sit squarely atop the musical hierarchy. In many ways the voice is the ‘benchmark’ for all melody, serving as the central sound that other instruments must emulate.

Carnatic vocals tend to be full and open-throated for both men and women. Low notes have a thick stability, and high register movements are loud and resonant, awash with intricate alankara (ornamentations). Aside from presenting pre-learned song forms, vocalists will improvise, calling on techniques such as niraval (‘expansion’), where a single line of text is repeatedly reworked and reinterpreted, and kalpanaswaram (‘notes of the imagination’), where singing is restricted to the syllables of the note names - Sa, Ri, Ga, Ma, Pa, Da , and Ni .

• Listen | Sudha Ragunathan dreamt of being a gynaecologist in her youth, but soon succumbed to music’s allure. Now a leading light of Carnatic song, she has released over 200 albums as well as writing for Tamil cinema. Outside of music she has picked up on her early medical ambitions by establishing the Samudhaaya Foundation, providing healthcare for those too poor to afford it. Here she sings Raga Abheri at Darbar 2013:

• Listen | The Malladi brothers (Sreeramprasad and Ravikumar) sing as a duet. Hailing from Andhra Pradesh, they are known for a mastery of the alapana (rhythmless introduction), often turning to rare ragam. Here the brothers sing a thillana by the late Lalgudi Jayaraman, one of Carnatic music’s ‘Violin Trinity’, set to Raga Rageshwari, a Northern import. Lalgudi Vijayalakshmi, the composer’s daughter, is on violin:

South Indian melodic instruments

The Saraswati veena is a large Carnatic lute, named after the Hindu goddess of arts and learning. Two large resonator gourds are joined by a hollow neck, and seven strings are suspended over 24 metal frets. The end is decorated with an ornamental dragon’s head ( yali ), symbolising the presence of Lord Vishnu.

The Atharvaveda , a 3,000-year-old collection of poetic mantras, discusses jaya ghosha (the musical sound of the archer’s bow string), pointing to one possible origin for the veena - although the basic principle of suspending a string against another object could have come from almost anywhere. Some scholars believe that primitive designs may have used bamboo for the neck, animal nerves for the strings, and a human skull for the resonating gourd.

Similar instruments turn up across Vedic literature, played by gods and rival kings, and some tales of the Buddha see him demonstrating concepts of spiritual balance using veena-string analogies. Yajnavalkya, the Vedic sage we met earlier, advised his followers that “one who knows the mysteries of the veena...will effortlessly find himself on the way to moksha [liberation from suffering]”.

But despite these most ancient of roots, today’s Saraswati veena is very much a modern instrument. The advent of the louder violin has left it somewhat drowned out in ensemble settings - the veena's strings must be slack to allow for wide bends, entailing a compromise on volume. Recent times have seen the rise of electrified veenas to counter this, although even the best of these fail to completely satisfy some acoustic purists.

• Listen | Dr. Jayanthi Kumaresh started playing the veena aged three, learning from her family and S Balachander. Now seen by many as its finest living exponent, she teaches and tours around the world. She also writes for dance and film, and has a PhD in veena history. Here she plays the eerily bluesy Raga Shanmukhapriya at Darbar 2013:

The violin has found more success on Indian classical stages than any other Western instrument. But the South Indian playing style is far removed from that of the West, with a focus on improvisation, rhythmic bowing, and intricate glides. The instrument’s head is held up against the knee to aid with its idiosyncratic sliding techniques, and the strings are also slackened (usually to around E3-B3-E4-B4, compared to the Western G3-D4-A4-E5).

Invented by Italian luthier Andrea Amati in 1555, the violin has been present in India since the 17th century, possibly introduced by the bandsmen of the British East India Company. It quickly gained popularity in classical circles, as musicians such as Balaswami Dikshitar (brother of Muthuswami) realised the potential of its loud, sustained timbres and microtonal capabilities. The instrument’s place at Carnatic’s top table was cemented in the 18th century by Vadivelu, a legendary composer and choreographer who studied it with a European missionary in Tanjore.

Since then, South Indian violinists have continued to push forward. The 20th century saw further stylistic innovation, notably from Dwaram Venkataswamy Naidu and the ‘Violin Trinity’ of TN Krishnan, Lalgudi Jayaraman, and MS Gopalakrishnan. The modern age has seen further innovation - L Subramaniam took the Carnatic violin back into Western orchestral settings , and his brother L Shankar has recorded acclaimed classical albums on his self-designed ten-string doubleneck violin .

Watching a Carnatic violinist can seem like a mystical, otherworldly experience, with virtuoso technique and dissonant, unfamiliar scales. Violin website Fiddling Around goes so far as to call it “one of the most exotic and mysterious of sounds”. But in some ways the Indian violin is actually played more like how you might expect it to be if you’d never heard one before. After all, why wouldn’t you slide around on a fretless instrument?

• Listen | Violins are often used in ‘pure’ duet performance, where both musicians have equal place as leaders. Here, Lalgudi GJR Krishnan and his sister Vijayalakshmi attack a fierce thillana at Darbar 2018. The piece, like the Malladi brothers example above, was written by their father Lalgudi Jayaraman:

South India has many other melodic instruments. These include the chitraveena (or gottuvadhyam ), essentially a fretless Saraswati veena, and stringless creations such as the venu , a bamboo flute, and the nadaswaram , a startlingly loud double-reed wind instrument.

Others have been imported in recent times. Kadri Gopalnath has adapted the saxophone to Carnatic music, customising its design to capture South India's microtonal articulations. He is now referred to by the honorary title Saxophone Chakravarthy (‘benevolent ruler, whose wheels are moving’). U Srinivas found acclaim for playing classical music on the electric mandolin, and Guitar Prasanna has made similar inroads for his own instrument.

Carnatic percussion

South Indian music is famed for its percussive imagination. There are hundreds of different rhythm cycles to choose from, and dozens of different drums to play them on. Here are those most commonly found on the classical stage:

The mridangam , a double-headed drum, usually leads the Carnatic rhythm section. Capable of a vast array of sounds, it anchors the music around it with booming bass thuds and a distinctive high-register bounce. Crafted from the wood of the jackfruit tree, it is also widely used to accompany bharatanatyam dance.

The instrument has a rich history. Prototypes were used to accompany early Hindu religious ceremonies, and Sanskrit epics such as the Ramayana refer to it by name, describing the mridang -like patter of breaking rainclouds. It is mythologised to have been played during Lord Shiva’s tandav dance of creation, sending primordial rhythms echoing throughout the heavens. Its sound anchors the instruments around it with booming bass thuds and a 'buzzing' high-register bounce.

• Listen | Neyveli B Venkatesh is a young Chennai-based mridangam player, renowned for superb solo performances. Here he stretches the 8-beat adi tala to its limits - recorded by Darbar on location in Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu:

Essentially just an earthenware pot, the ghatam is often paired with the mridangam . Fashioned from clay, sometimes mixed with metal filings for a sharper tone, it is roughly spherical, there is a small opening to release the sound. Simplicity is no barrier to variety - musicians use their nails, fingers, palms, wrists, and elbows to summon a dazzling array of textures.

The main tones all have a sharp metallic crack. But this initial punch quickly fades away, leaving an overtone-rich echo. Fast sequences are a rain-like patter, full of flourish and ambiguous resolution. Drummers flick, tap, and slap, and go low too - they can strike the opening with a flat hand to produce gumki , a deep, airy bass.

The ghatam is said to represent the pancha mahabhuta - the five great elements of Hindu metaphysics. Made of earth ( bhumi ), it is designed to hold water ( jala ), hardened in a kiln’s fire ( agni ), filled with empty space ( akash ), and produces sound with moving air ( vayu ).

• Listen | Young star Giridhar Udupa learned several Carnatic percussion instruments before settling on the ghatam. In his words, “It is a simple clay pot. What amazes people is how such a pot can produce such good sound”. Here he discusses his life in music, demonstrating along the way:

The tambourine gets a lot of stick in the West. But the kanjira , its Carnatic cousin, suffers from few of the same prejudices. Originally a folk instrument, it was adopted onto the classical stage in the early 20th century.

The setup is comparatively simple - a thin layer of lizard skin is attached to a circular wooden frame, and played with the fingers and palms. The skin can be stretched to raise the pitch mid-stroke, and the overall tone can be lowered by sprinkling water on the inside of the drum.

• Listen | G Guruprasanna is a young kanjira master. He trained under G Harishankar, and has accompanied a swathe of top classical artists as well as delving into jazz. Here he demonstrates the full sonic range of his instrument:

There are others too. The morsing (jaw harp) is somewhere between a drum and a drone. Its syllabic roll has a weightless, warm shiver, speaking as much as singing. Traditionally made of iron, a metal ‘tongue’ is plucked with the fingers, transferring vibration to the player’s head via the front teeth. The skull becomes the amplifier, and some use the sensation to aid with pranayama (breathing meditation). In classical settings it often mirrors and embellishes the lead lines of the mridangam .

Other distinctive percussion instruments include the thavil , a large barrel drum played with one hand and one stick, and the udukkai , an hourglass-shaped drum that can be made to ‘talk’ by squeezing the ropes that tension the skin. There are an astounding number of regional folk drums, many of which defy easy categorisation (n.b. does anyone know what on earth this elastic-band sounding drum might be? Even top Carnatic artists I’ve asked don’t seem to have any idea...)

Solkattu: speaking rhythm

Carnatic percussion also features the use of solkattu , a system of onomatopoeic sounds intended to ease the process of internalising rhythm (the word translates as ‘a bunch of syllables’). The musician claps along with the underlying cycle while ‘speaking’ the drum strokes - such as Ta , Di , Na , and Thom .

It is versatile, beautifully concise, and doesn’t require an instrument - you can learn and dissect rhythms wherever you happen to be at the time. The practical, vocalised aspect of solkattu , known as konnakol , was once a common part of Carnatic concerts, but this trend is diminishing today.

• Listen | Dr. Trichy Sankaran is a global ambassador for the mridangam. He has lived in Canada for the past half a century, teaching and collaborating with dancers, jazz groups, classical orchestras, Gamelan ensembles, and West African drummers. Here he gives a quick demonstration of solkattu:

Basics of ragam and talam

Carnatic music is famed for its theoretical complexity. Even its name is a signal in this direction, thought by some scholars to derive from the term Karnataka Sangeetham , Sanskrit for ‘traditional, codified song’ (although others consider it to be a combination of karna and ata - meaning 'to haunt the ear').

You definitely don’t need to know any theory to enjoy the music on profound levels, but learning a little about how it works only tends to enhance your appreciation. Here are the basics of Carnatic theory - all terminology is explained as we go, but there’s a lot to take in...

Ragam: melodic mood recipes

The concept of ragam defines how Carnatic musicians approach melodic improvisation. The term roughly translates from Sanskrit as ‘dye, hue, that which colours the mind’, although there is no clear English equivalent. A ragam is an aesthetic concept as well as technical one - while musicians must follow detailed rules as they play, conforming to them is not the point. Instead, they focus directly on conjuring particular bhavas (emotions) and rasas (a Sanskrit concept translating as ‘juice, taste, essence’).

Each ragam contains a wealth of musical information, designed to help summon the intended mood. This includes the set of permissible swaras (notes), their exact sruti (microtonal tunings), the sancharam (characteristic phrases), and some suggested gamakas (ornamentations). Most take five to seven notes in total, specifying the most important as the vadi and samvadi (king and queen tones).

But a ragam cannot be understood as a purely musical object. They are culturally embedded, interconnected phenomena, with emotional signifiers that stretch far beyond the realm of sound. To take an example, Raga Hamsadhwani is made of five notes ( SRGPN - in Western terms a major scale with the 4th and 6th degrees removed), and specifies Sa and Pa (1st and 5th) as the most important. But there is much more to the ragam too, all of which the musician should bear in mind.

Hamsadhwani translates to ‘call of the swan’, a creature with rich associations in Indian culture. Saraswati, the goddess of music and learning, is often depicted atop a swan, said to symbolise purity, discernment, and the process of breathing. The ragam also has a historical association with Lord Ganesha, the elephant-god believed to protect the arts and remove obstacles from the paths of those who are truly dedicated. See what you can hear of all this in TM Krishna’s exposition:

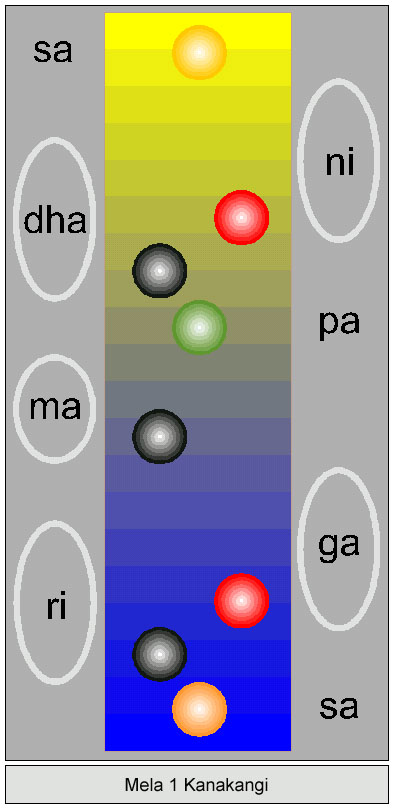

Carnatic ragam , numbering several hundred, are classified using the intricate katapayadi system. This approach relates any given set of notes to the Melakarta (‘lord of the scales’), a collection of 72 ‘parent’ sequences. ( For theory nerds: this number represents the number of seven-note combinations possible under Carnatic music’s traditional axioms, which keep the Sa and Pa (1st and 5th) fixed, while allowing for two variants of Ma (4th) and three each for the other tones - Ri, Ga, Dha, and Ni (2nd, 3rd, 6th, and 7th). This can be reduced to 2 x 6 x 6, equalling 72 - more info on how katapayadi works here ).

‘Pure’ Melakarta ragas - those containing the same seven notes in ascent and descent - are known as janaka (‘father’) scales. But Carnatic artists, not content with a mere 72 options, also call on numerous janya (‘begotten’) ragas.

Though the name suggests they all ‘derive’ from some parent scale, many janya ragas pre-date the Melakarta system entirely, arising instead from folk tunes and other sources. Unlike the janaka scales, janya ragam usually have less than seven notes. They can also differentiate themselves by taking a vakra (zig-zag) structure, or specifying different sets of tones for the ascent and descent ( arohanam vs. avarohanam ).

"Music is based on praising the gods, first of all..." (D Srinivas). Photo: Darbar

Talam : rhythm cycles

Carnatic musicians refer to rhythms as talam (‘clap’). They are felt as cycles, endlessly rotating back to a fixed origin point like the hands of a clock. A wide variety of different rhythm cycles are in use, of which the most common is the 8-beat adi tala (Sanskrit for ‘primordial rhythm’):

Other popular choices include the 6-beat rupaka tala , the 4-beat eka tala , and odd-time cycles such as the 5-beat khanda chapu and the 7-beat misra chapu ( chapu is a Tamil-derived word meaning ‘slanted, sloping’). Available forms stretch right up to the 128-beat simhanandana tala , in use since at least the 18th century.

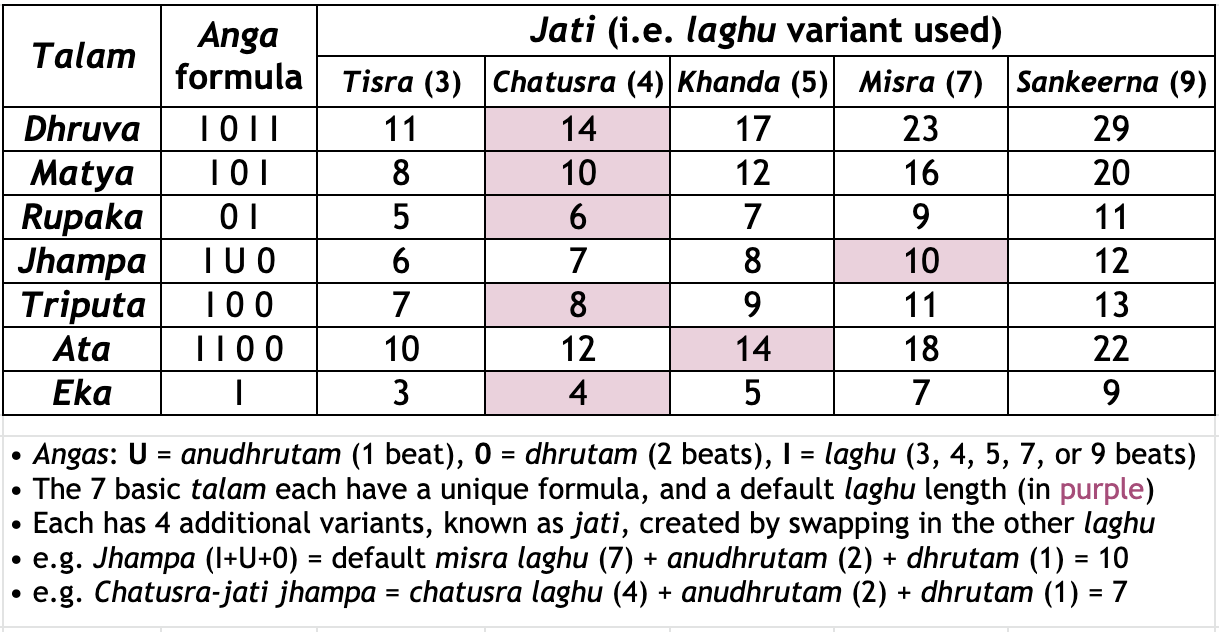

As with ragam , Carnatic musicians navigate the world of talam using detailed mathematical frameworks. Each talam is seen as being composed of distinct sections, known as angas (‘limbs’). The most common angas are the anudhrutam (1 clap/beat), the dhrutam (2 claps/beats), and the laghu (a variable pattern with either 3, 4, 5, 7, or 9 beats, counted on the fingers). See if you can count out the subdivisions in the following three talam - rupaka (6 as 2+4), khanda chapu (5 as 2+3), and misra chapu (7 as 3+4):

The names of the talam function like a shorthand for how different angas should be combined to play them. For example, rupaka (the first rhythm in the clip above) signifies ‘ dhrutam + laghu ’, or ‘2 beats plus a variable pattern’. Rupaka uses the 4-beat chatusra laghu by default, giving an overall total of 2+4=6. But laghus of other lengths can also be swapped in to create types of rupaka , including tisra (3 beats), khanda (5 beats), misra (7 beats), and sankeerna (9 beats).

Changing the laghu does not change the talam ’s underlying formula (in the case of rupaka , ‘ dhrutam + laghu ’) - it just alters the ingredients you put into it. For example, the variant of rupaka talam known as sankeerna-jati rupaka has the same basic formula, but calls for the use of the 9-beat sankeerna laghu in place of the default 4-beat chatusra . So the formula of dhrutam + laghu is now unpacked as ‘2-beat dhrutam plus 9-beat laghu ’, extending the overall length of the cycle from 2+4=6 to 2+9=11.

The Suladi Sapta Tala system plays a similar role for rhythm as the Melakarta does for melody, classifying much of the standard repertoire into a defined framework to aid with learning and understanding. It specifies seven basic time cycles, all defined by a unique formula. Each has a ‘default’ laghu along with four variants, corresponding to the five types of laghu on offer. The system thus contains a total of 35 different talam (7 scales x 5 variants = 35):

To further complicate things, each individual akshara (beat) can in turn be subdivided. The Carnatic theory of gati (‘speed’) dictates how this is done. Also referred to as nadai , the concept ‘slices up’ each beat into a specified number of identically-sized segments, allowing musicians to ‘jump’ between different levels of rhythmic density without straying from the underlying cycle.

The five types of subdivision on offer use the same numbers and names as the five jati - tisra (3), chatusra (4), khanda (5), misra (7), and sankeerna (9). A musician soloing in chatusra gati will, in simple terms, play four notes per beat. Moving to khanda gati will see them squeeze five notes into the same time interval, raising the intensity:

The cognitive effect of this ‘jump’ is ambiguous. In a way the music has sped up, and in a way it hasn’t. There’s a lot more going on within each beat now, but the main beats themselves haven’t shifted position at all. The stable, steady progression of the basic cycle contrasts with the frantic, odd-numbered streams of notes flowing over it, creating unique tensions. Applying the five varieties of gati to each of the 35 Suladi Sapta talam gives a total of 175 different rhythms (7 basic talam x 5 jati variants x 5 gati levels = 175).

Carnatic drummers have plenty of other tricks, including methods of drastically slowing the rhythm down, stretching it out to only half or a quarter of its original speed (like an inverse of gati ). And the Suladi Sapta talam are only a fraction of the total on offer. There are also 108 anga talam , most of which require building blocks other than just the dhrutam , anudhrutam , and laghu . And the 72 Melakarta talam were designed to match with the full set of parent ragam . But that will do for now.

Don’t worry if this is all a lot to take in at first. It takes a while to get used to, and you have to feel the numbers rather than just count them. For further reading/watching/recapping see Dr. Trichy Sankaran’s hour-long intro lecture on the Darbar Player, and also Jahnavi Harrison’s excellent article Carnatic Rhythms 101: How to slap your thigh like a pro .

• Listen | Trichy Sankaran and Giridhar Udupa engage in a fiery tani avartanam (percussion section) as part of the Lalgudi siblings' concert at Darbar 2018:

Mixed forms: ragamalika and talamalika

Popular for centuries, the Carnatic ragamalika (‘garland of ragas’) blends a group of ragam into a single piece. They enable the artist to create quick-swerving musical narratives, showcasing shades of emotional contrast unavailable within the confines of a single ragam . Composers turn to whichever scale they deem most suitable for the next moment, and musicians aim to ensure the points of transition are noticeable but natural.

19th century vocal pioneer Maha Vaidyanatha Sivan once composed a half-hour ragamalika featuring all 72 Melakarta scales. Lavani Venkata Rao, a percussion-playing poet of the Thanjavur court, had written a collection of verses praising the ruler’s son-in-law, and Sivan was tasked with setting them to music.

He did so in under a week, creating his famous ragamalika , and was rewarded with money and gifts. But later he came to resent the original lyrics, which not only glorified a mortal man rather than the gods, but did so using imagery that was often highly erotic. He wrote new words, praising Lord Shiva, and this second version is still in circulation today (listen to it here ).

The ragamalika ’s rhythmic equivalent, the talamalika , places different time cycles together in one composition. The talam are ordered carefully to give a coherent overall flow, and musicians must stay alert to the jumps. A ragamalika and a talamalika can in turn be combined, creating a ragatalamalika (a concept so full of music that even its name sounds like a mini-melody).

18th century composer Ramaswami Dikshitar (father of Muthuswami from the Trimurti ) is regarded as the king of malika forms. He once blended 108 ragam and talam into a single piece, the Ashtottara Sata Ragatalamalika , often reputed to be the longest in all of Carnatic history.

The work recites the many names of Devi, Hinduism’s supreme goddess, setting each to a different rhythmic-melodic combination. It employs shlesha (lyrical double meaning), subtly working the names of the ragam and talam into the main text. Sadly, all but the first 61 sections have been lost.

• Listen | Ganesh and Kumaresh displayed prodigious talent from early childhood, developing a shared style that garnered praise for maturity as well as technical brilliance. The brothers have both found success as soloists, but more often than not choose to play as a duet. In their words, “We share. We argue. We fight. We come to a consensus. We have grown like this. We have grown the art also this way...”. Here they play a superb ragamalika, live from Darbar 2009:

What even is theory anyway?

In contrast to the structured approaches of the West, Carnatic music theory is a loosely delimited phenomenon. It is not just about sitting down to study ragam rules and rhythm formulas. For a dedicated musician, learning is an entire mode of existence, inclusive of everything from technical facility to the way they walk to the instrument and clear their mind before a performance. After all, no aspect of living seems irrelevant to an artist who seeks to give their whole being to their craft. Music theory, seen this way, can encompass all of life.

Music in motion: three modern innovators

As previously mentioned, Carnatic music is a living, breathing tradition, with musicians constantly assimilating new ideas and responding to an ever-changing world. Here are three modern Carnatic masters, all of whom have expanded the boundaries of the music in their own distinct ways.

• Shashank Subramanyam was born to a biochemist father in the extraordinarily musical village of Rudrapatna. An early starter even by Indian classical standards, he had mastered all 72 Melakarta scales by the age of two and a half, prompting a research team to study his prodigious talent.

Though his first musical immersions came with singing and violin, he fell in love with the venu flute as soon as he picked it up, focusing on it from that point onwards. Initially he taught himself, but soon entered the discipleship of TR Mahalingam. His guru insisted that he continue his vocal training, and also that he avoid listening to other top masters of the day so as to develop his own sound.

The approach worked - his style overflows with fresh melodic thinking, incorporating novel breathing patterns and extended techniques such as overblowing. He has imported ideas from Hindustani music, and worked with global icons including minimalist composer Terry Riley, flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucia, and Indo-jazz heavyweights Remember Shakti.

• Listen | Shashank leads a full Carnatic group through Raga Vagadeeshwari. His melodies are exuberant to the point of mania, bursting with divine feats of rhythmic agility. Have you ever heard a flute played anything like this before?

• Rajhesh Vaidhya was born into a family of Tamil Nadu percussionists. At first he wanted to be a drummer too, but eventually followed his mother’s wish to play the Saraswati veena instead. He trained under various gurus including Chitti Babu, a legend of the instrument, and continues to study with violinist L Shankar. He has worked with artists including AR Rahman and Elton John, and now runs his own music academy.

His veena is electrically amplified, and customised in other ways too. In his words, “During a trip to Germany I saw a wire lying on the floor in my hotel room. It turned out to be an electric wire. I strung it on to my instrument and loved the sound it produced. Ever since, the wires have replaced the regular strings of my veena ”.

• Listen | Rajhesh, who recently got a tattoo of a veena on his arm, brings a playful touch to all he does. His energetic version of Raga Kafi is renamed ‘Kafi Espresso’:

• TM Krishna is known for eloquent social progressivism as well as a sublime mastery of Carnatic song. He believes that classical music should not be confined to the establishment, lamenting its recent history as the “cultural preserve of the Brahmin caste, performed, organised, and enjoyed by the elite”. He has consistently put his principles into practice, teaching in the slums of Chennai and working with transgender jogappa musicians in Karnataka.

Born into a culturally-inclined business family, he learned to sing from early childhood, honing his craft under the tutelage of Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer. His present style is renowned for a soulful, sincere treatment of melody, full of deep textures and lyrical meaning. He often sets unorthodox texts to rare ragam , and has irked traditionalists by rearranging the format of his concerts, sometimes placing the varnam in the middle rather than at the start.

He is a prominent public advocate for various left-wing causes, and has published acclaimed books on the sociopolitical nature of art. He speaks out against economic inequality, caste-based discrimination, and the Hindutva nationalist movement, and a commitment to religious pluralism has seen him perform in Christian churches and sing songs to Allah.

• Listen | In 2017 TM Krishna collaborated with environmental activist Nityanand Jayaraman on Chennai Poromboke Paadal, a ragamalika composition which protests the pollution of Chennai’s Ennore creek by a nearby power plant. Poromboke is an old Tamil word for a shared-use community resource, but has in modern times become a pejorative, suggestive of worthless people or places:

Carnatic ideas around the world - and what next?

South India’s classical music has a long, illustrious history. But its future is uncertain - while the music itself thrives, its social reach has undergone a curious transformation over the past half-century. The advent of pop and other forms of commercial entertainment has eroded its appeal within India, but Carnatic ideas have now gone global, with a hidden influence on countless different genres.

Jazz guitarist John McLaughlin followed in the lead of his idol John Coltrane by studying India’s classical traditions in depth. But unlike Coltrane, it was the music of the South that captured his attention most. A few years after leaving Miles Davis’ electric ensemble he formed the all-acoustic Shakti group, featuring L Shankar on Carnatic violin, TH ‘Vikku’ Vinayakram on ghatam , and Zakir Hussain on North Indian tabla . Often described as the world’s first true global fusion band, their music makes exquisite use of konnakol and other South Indian ideas (see my full article on how they use a cyclical view of time to flow in odd meter).

Others have built their own sonic bridges to South India. American ethnomusicologist Jon Higgins dedicated himself to learning Carnatic vocal music, becoming one of the first Westerners to receive acclaim for performing it to Indian audiences. Early reviews in The Hindu newspaper express wonder at how a “Connecticut Yankee” could sing with such “remarkable empathy for the grammar and idiom of Carnatic song”, and he eventually became known by the honorific Higgins Bhagavatar (scholarly master).

John 'Bhagavatar' Higgins

British vocalist Susheela Raman draws on her Tamil heritage for jazz-folk inspiration, and American saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa looks to his own South Indian roots as well as to bebop. Carnatic rhythm has found particular global success, entrancing musicians of various persuasions - affable Swedish ‘freak guitarist’ Mattias IA Eklundh uses it, as do modern jazz drummers such as Asaf Sirkis and James Vine . Few have gone further in than Equatorial Guinea-born percussionist Rafael Reina , who has written a superbly detailed 500-page book called Applying Karnatic Rhythmical Techniques to Western Music .

Influence has gone the other way too, with Carnatic artists increasingly importing ideas from outside India. This is hardly a new phenomenon - Shyama Shastri was adapting Celtic folk tunes for his Nottuswara suite almost 200 years ago - but the pace has accelerated sharply in recent times. In the words of Dr. Trichy Sankaran , the master mridangist we met earlier, “Other music strengthens everyone, and provides more ideas for the musician. We can bring out more of our personality this way”.

Sankaran told me in an interview that he has picked up ideas from the Hindustani tabla , and even finds himself dropping the West African gankogui rhythm into classical accompaniment. Others look in different directions - VS Narasimhan ’s Carnatic string quartet adds harmony to the music, and L Shankar uses European bowing techniques in his virtuosic ragam-tanam-pallavi performances.

Young vocalist Varijashree Venugopal has achieved online fame for her sargam renditions of jazz standards such as Giant Steps , and BC Manjunath has done the same by turning the Fibonacci series into konnakol compositions:

The music is changing from within too. Sankaran gave me his take on recent rhythmic trends: “Modern performers are into quite cerebral types of creation - more abstract and mathematical. I appreciate how they have furthered the art...but the ability to appreciate slow music is disappearing...some of the slowest talas are near-obsolete now”. He also laments the decline of the ‘full bench’ percussion section ( mridangam , ghatam , kanjira , morsing , and konnakol ), but remains optimistic about the overall direction of the music.

Today’s Carnatic world exemplifies many of the Subcontinent’s broader cultural clashes, throwing up test cases on issues such as gender, religion, and corporate overreach. Some of these suggest the music’s social foundations may be moving in a less progressive direction - TM Krishna has had concerts cancelled due to threats from Hindu nationalists, incensed by his refusal to drop Christian-themed songs from his repertoire (despite the fact that Indian-born Christian composers have featured in South Indian classical since the 1790s ).

Other flashpoints, though painful, are evidence that times may be changing for the better - the Madras Music Academy dropped seven artists from its 2018 Margazhi season over #metoo allegations, setting a stronger precedent than Hindustani music has yet managed ( to put it mildly ).

Vocalist Aruna Sairam is broadly positive about how opportunities for young female singers are improving, although the corporate sponsorship on which it is often based is not without controversy. As the Economic Times of India puts it , "A generations-old music festival in Bengaluru regretfully tells aspiring young musicians...'Maybe you are really good, but there are many like you for the junior slots. Difficult to choose. But if you can bring a sponsor we will give you a slot'".

The music retains its global pull, fostering fertile discussions on Reddit and packing thousands of kutcheri outside the Subcontinent each year (n.b. come and see some in London at Darbar 2019 ). Aruna is intrigued by how the music can lead India’s diaspora population back to the Subcontinent: “Now we have students from America who first learn in California, then move to Tamil Nadu to further their studies”.

She also hails the broad listening opportunities available online (“I am grateful to the listeners who have appreciated my music and uploaded it on YouTube”). and is enthusiastic about how the internet can demystify Carnatic ideas for outsiders (...I hope you’re already somewhat persuaded if you’ve read this far in).

12th-century musical carvings from Karnataka's Hoysaleswara Temple

It sometimes feels like the Carnatic tradition is simultaneously one of the world’s best- and worst-kept musical secrets. It has always struggled to command anything like the global attention of its Northern cousin, but has nevertheless managed to entrance a diverse array of international musicians for over half a century now, exerting influences hidden in plain sight along the way. Now, as ever, it reflects the complex struggles and value clashes of the society in which it exists.

Predicting the precise future paths of a millenia-old tradition is a probably fool’s errand, especially for a distant Westerner such as myself. However, this fact may hint at its own answer - if the music has survived for this long then we should believe in the power of its core elements. But this is no reason for complacency. Musical cultures which fail to adequately balance tradition and innovation find themselves consigned to the history books, and we will never know the full extent of what has been lost like this.

For what it's worth, my two rupees is that the Carnatic music will remain relatively robust for generations yet, protected by the inherent strengths of its ingredients - disciplined, ear-based teaching, playful rhythmic mathematics, and a liberating blend of composition and improvisation. The tradition may change drastically over time, but will remain a spiritual endeavour, opening the doors to the spontaneous aspects of the mind, body, and soul.

• George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specialising in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.

• Listen | Aruna sings the same thillana as in the very first video, again live from London. However this time she is accompanied by a truly global blend of instruments - jazz piano, Hindustani sarod , Irish bodhran drum, and Carnatic percussion:

Darbar believes in the power of Indian classical music to stir, thrill, and inspire. Explore our YouTube channel , or subscribe to the Darbar Concert Hall to watch extended festival performances, talk and documentaries in pristine HD and UHD quality.

Be notified when we add a new articles

Be the first to know about early bird tickets, special offers, new music and never miss the best of Darbar, simply click here to be in the know! Privacy Policy .

Article Categories

- New to Indian Music

Performing at Darbar Festival 2020

Festival 2024

Other articles you may like

The Violin: a Western instrument takes centre stage in...

The Pecking Order: Why is vocal music considered the highest...

The Mridangam: an ancient, divine drum

New to indian classical music.

The beginner's guide to Indian classical music. Whether you’re completely new to raga music or just need a refresher, we’ve put together this brief overview of all things raga music to help you feel at ease when visiting one of our concerts or watch our videos on our YouTube or our Darbar Concert Hall.

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, music and musings across our social channels

YouTube latest

Subscribe to our newsletters

Be the first to hear before events go on sale. Get the latest news and articles from Darbar

carnatic music in a glance

By Spardha Learnings | October 23, 2024

Table of Contents

Learning music is very similar to learning a new language, starting with the alphabet, then words, and sentences. There is a wide variety of musical genres including Carnatic Music, Hindustani Music, Western Music and so on. And Hans Christian Anderson’s inspirational words apply to all kinds of music -

“ Where words fail, Music speaks” .

So, where does Carnatic Music fit into this? To understand that, let’s first understand what Carnatic Music is.

1. What is Carnatic Music?

Carnatic music, commonly known as Classical Music is a colorful and complete form of Indian Classical Music with origins in Southern India. Carnatic music owes its name to the Sanskrit term Karnātaka Sangītam which denotes “traditional” or “codified” music.

Carnatic music follows a fixed structure which applies to the learning process as well. We start with learning the sruthi (pitch) , swaras (letters) , swarasthanas (positions of the swaras) , then ragas (tunes) , talam ( rhythm ) and finally, it turns into a beautiful song.

Carnatic music is one of the world's oldest & richest musical traditions with 7 fundamental swaras, 16 swarasthanas, 72 basic scales on the octave, and a rich variety of melodic motion.

Carnatic music is one of the two main subdivisions of Indian Music rooted in the ancient Hindu texts and traditions, particularly Samaveda. This is why Carnatic music has such a rich cultural heritage.

The other subdivision is Hindustani Music with origins in Northern India.

Carnatic Music combines melody, rhythm and lyrics. The main emphasis in Carnatic Music is on Vocals. Most compositions are written to be sung, and even when played on instruments, they are meant to be performed in Gayaki (singing) style. The majority of compositions are on the theme of devotion, love towards divinity. A few instruments are also used as the accompaniment, such as Tanpura for sruthi, Mridanga, ghatam for rhythm, violin and a few instruments like Morsing, Veena and Flute.

2. Why Carnatic Music?

Carnatic music demands attention so much that the listener is truly immersed in the song. This immersion is very close to meditation and thus provides the positive benefits of calming the mind.

Carnatic music follows a directness of the expression and the range of melodic material available is highly diverse. A song can be performed simply and in all humility, or with the grandest elaboration retaining the core of both meaning and melody.

While learning Carnatic music , you not only learn the rich musical tradition but also gain an understanding of the Indian cultural heritage. You learn to sing and easily identify the ragas of the song in your Carnatic music classes and in addition, it also helps you improve your concentration level, create a great personality, develop patience, and remove negative thoughts from the mind.

The success of music is ultimately in the mind of the listener, and specifically in the physical and emotional changes which can be provoked. It is a simple fact that Carnatic music has only a positive effect in this way, while the same cannot be said for various forms of popular music. This is because Carnatic music demands attention so much that the listener is truly immersed in the song. This immersion is very close to meditation and thus provides the positive benefits of calming the mind.

Both the ability of music to build and release tension as well as its potential to unlock latent energies in the mind are respected and developed. And of course. the meaning of the lyrics revolves around acts of religious devotion which also adds to the feeling of sublimity.

Carnatic music is usually performed by a small group of musicians who sit on an elevated stage. This usually consists of, at least, a principal performer (usually the vocalist) , a melodic accompaniment, a rhythm accompaniment, and a drone.

Carnatic music is usually learned through many compositions. Telugu language predominates in the evolution of Carnatic music. Most Carnatic compositions are in Telugu and Sanskrit along with some in Tamil and Kannada.

3. How does Carnatic Music differ from Hindustani Music?

There are many similarities between Carnatic and Hindustani music since they have both evolved out of Indian Classical Music.

But there are also several differences that distinguish the two styles. The two styles differ in instruments, structure, swarasthanas, ragas, vocal usage, language and approach to improvisation.

Given below are the very basic differences between Carnatic and Hindustani Music.

Carnatic Music VS Hindustani Music

4. Some of the popular Carnatic compositions by different composers

Mahaganapathim in raga Nattai

Devadeva Kalayaamithe in raga Mayamalavagoula

Vathapi Ganapathim Bhaje in raga Hamsadwani

Samajavara gamana in raga Hindolam

Carnatic music is one of the world's greatest treasures and the journey of learning Carnatic music will take one to a different peaceful world.

Share this post on:

Carnatic Music, Meaning, Origin, Instruments, Ragas

Carnatic Music deeply rooted in southern India, has ancient origins intertwined with cultural, religious and historical influences. Get all about Carnatic Music, Meaning, Origin, Instruments, Ragas.

Table of Contents

Carnatic music, deeply rooted in the southern regions of India, boasts a sophisticated theoretical foundation centred around Ragam (Raga) and Thalam (Tala). Purandaradasa (1480-1564), revered as the father of Carnatic music, systematized its methods and authored numerous compositions, codifying the musical system. Venkat Mukhi Swami, a luminary, developed the classification system “Melankara” for South Indian ragas. In the 18th century, the Trinity—Thyagaraja, Shama Shastri, and Muthuswami Dikshitar—emerged, compiling compositions that define the Carnatic music repertoire, marking a pivotal period in its evolution. This classical tradition continues to enchant with its rich heritage and nuanced musical expressions.

We’re now on WhatsApp . Click to Join

Carnatic Music Origin

Carnatic music, one of the classical music traditions of India, has ancient roots that can be traced back over several centuries. The origin of Carnatic music is deeply embedded in the cultural and religious practices of the southern regions of India, particularly in present-day Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Kerala. While it’s challenging to pinpoint an exact date or origin, the development of Carnatic music can be understood through historical and cultural contexts.

Key factors in the origin and development of Carnatic Music include:

Ancient Scriptures and Traditions

- Carnatic music has strong ties to ancient Indian scriptures, particularly the Sama Veda, which is one of the four Vedas and contains hymns set to music. The musical elements in the Sama Veda laid the foundation for the intricate melodic and rhythmic structures found in Carnatic music.

Temple Traditions

- Temples played a significant role in the development and preservation of Carnatic music. Musical performances were integral to temple rituals, and the rich musical heritage was passed down through generations within the temple settings.

Bhakti Movement

- The Bhakti movement, which gained prominence between the 6th and 17th centuries, contributed to the development of devotional music. Saints and poets, known as Alwars and Nayanars in the Tamil tradition, composed devotional verses that later became part of the Carnatic music repertoire.

Influence of Medieval Composers

- During the medieval period, composers like Purandaradasa (15th-16th century) made significant contributions to the systematization and codification of Carnatic music. Purandaradasa is often considered the father of Carnatic music for his role in organizing the melodic and rhythmic aspects of the tradition.

Trinity of Carnatic Music

- The 18th century saw the emergence of three prolific composers—Thyagaraja, Shama Shastri, and Muthuswami Dikshitar, collectively known as the Trinity of Carnatic music. Their compositions further enriched the Carnatic music repertoire, and their contributions are considered foundational to the tradition.

Oral Tradition and Guru-Shishya Parampara

- Carnatic music has been primarily transmitted through an oral tradition, with knowledge passed down from guru to shishya (teacher to disciple). This guru-shishya parampara (teacher-disciple tradition) remains a fundamental aspect of learning and preserving Carnatic music.

The origin and evolution of Carnatic music are complex and multifaceted, influenced by religious, cultural, and historical developments over the centuries. The tradition continues to thrive as a classical art form with a rich and intricate musical heritage.

Key Aspects of Carnatic Music

Carnatic music is one of the classical music traditions of India, with its roots in the southern part of the country. It is one of the two main traditions of Indian classical music, the other being Hindustani music, which is prevalent in the northern part of India. Here are some key aspects of Carnatic music:

Raga (Melodic Framework)

- Definition: A raga is a melodic framework used in Indian classical music, providing a set of rules for building a melody. Each raga has specific ascending (Arohana) and descending (Avarohana) note patterns, defining its unique character.

- Emotion and Mood: Ragas are associated with specific moods, times of the day, and seasons. For example, the raga Bhairavi is often associated with devotion, and it is traditionally performed in the early morning.

Tala (Rhythmic Cycle)

- Definition: Tala refers to the rhythmic cycle or beat pattern in Carnatic music. It is a fundamental aspect that structures the temporal dimension of the music.

- Variety of Talas: There are numerous talas with varying numbers of beats, such as Adi Tala (8 beats), Rupaka Tala (6 beats), and Misra Chapu (7 beats). The rhythmic intricacies contribute to the dynamic nature of Carnatic performances.

Krithis and Varnams

- Krithis: These are longer and more complex compositions that include both lyrical and melodic elements. They often convey deep philosophical and devotional themes. The Trinity of Carnatic music—Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Shyama Shastri—composed numerous krithis.

- Varnams: Shorter compositions that serve as warm-ups or practice pieces. They are characterized by fast and intricate patterns, helping musicians develop technical proficiency.

Carnatic Instruments

- Veena and Violin: String instruments like the veena and violin are commonly used in Carnatic music. The violin, in particular, plays a crucial role in accompanying vocal performances.

- Mridangam and Ghatam: Percussion instruments like the mridangam (double-headed drum) and ghatam (clay pot) provide rhythmic support. The mridangam player has the challenging task of interpreting and enhancing the nuances of the melody through percussion.

Concert Structure

- Vocal Tradition: While instruments play a vital role, vocal music is considered the core of Carnatic tradition. Vocalists are trained to explore the full range of their voices, emphasizing expression and emotion.

- Concert Components: A typical concert includes a varnam as an opening piece, followed by various krithis in different ragas and talas. The artist may also present alapana (improvisation), neraval (elaboration of lyrical lines), and swara kalpana (melodic improvisation).

Guru-Shishya Parampara

- Oral Tradition: Carnatic music is traditionally passed down orally from guru to shishya. This direct, personal transmission allows for a deep connection between the teacher and the student, fostering a holistic understanding of the art.

Rasas (Emotions)

- Expressive Elements: Musicians aim to evoke specific emotions or rasas through their performances. The interaction between raga, tala, and expressive techniques such as gamakas (ornamentation) contributes to the emotional impact.

Great Composers

- Trinity of Carnatic Music: Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Shyama Shastri are revered as the Trinity of Carnatic music. Their compositions form the backbone of the repertoire, and musicians continue to interpret and present their works in diverse ways.

Carnatic music, with its rich heritage and intricate structure, is a profound art form that continues to captivate audiences around the world. The balance of melody, rhythm, and emotion creates a musical experience that transcends cultural boundaries.

Carnatic Music UPSC

Carnatic music, deeply rooted in southern India, has ancient origins intertwined with cultural, religious, and historical influences. Purandaradasa, the father of Carnatic music, systematized its methods, and the Trinity of Carnatic music—Thyagaraja, Shama Shastri, and Muthuswami Dikshitar—emerged in the 18th century, shaping its repertoire. This classical tradition revolves around the intricate concepts of Ragam and Thalam, with a rich theoretical foundation.

Ancient scriptures, temple traditions, the Bhakti movement, and the oral guru-shishya parampara played pivotal roles in its development. Carnatic music continues to enchant with its nuanced expressions, highlighting the harmonious blend of melody, rhythm, and emotion.

Sharing is caring!

Carnatic Music FAQs

What is carnatic music.

Carnatic music is a classical music tradition of South India, known for its intricate melodic and rhythmic structures.

Who is considered the father of Carnatic music?

Purandaradasa (1480-1564) is revered as the father of Carnatic music for systematizing its methods and composing numerous songs.

What is "Melankara" in Carnatic music?

"Melankara" is a classification system for South Indian ragas, developed by the luminary Venkat Mukhi Swami.

Who are the Trinity of Carnatic music?

Thyagaraja, Shama Shastri, and Muthuswami Dikshitar, known as the Trinity, are prolific composers who significantly enriched the Carnatic music repertoire in the 18th century.

Greetings! I'm Piyush, a content writer at StudyIQ. I specialize in creating enlightening content focused on UPSC and State PSC exams. Let's embark on a journey of discovery, where we unravel the intricacies of these exams and transform aspirations into triumphant achievements together!

- art and culture

Trending Event

- SSC CGL Tier 1 Answer Key 2024

- RPSC RAS Apply Online 2024

- TNPSC Group 2 Answer Key 2024

Recent Posts

UPSC Exam 2024

- UPSC Online Coaching

- UPSC Syllabus 2024

- UPSC Prelims Syllabus 2024

- UPSC Mains Syllabus 2024

- UPSC Exam Pattern 2024

- UPSC Age Limit 2024

- UPSC Calendar 2025

- UPSC Syllabus in Hindi

- UPSC Full Form

- UPPSC Exam 2024

- UPPSC Calendar

- UPPSC Syllabus 2024

- UPPSC Exam Pattern 2024

- UPPSC Application Form 2024

- UPPSC Eligibility Criteria 2024

- UPPSC Admit card 2024

- UPPSC Salary And Posts

- UPPSC Cut Off

- UPPSC Previous Year Paper

BPSC Exam 2024

- BPSC 70th Notification

- BPSC 69th Exam Analysis

- BPSC Admit Card

- BPSC Syllabus

- BPSC Exam Pattern

- BPSC Cut Off

- BPSC Question Papers

SSC CGL 2024

- SSC CGL Exam 2024

- SSC CGL Syllabus 2024

- SSC CGL Cut off

- SSC CGL Apply Online

- SSC CGL Salary

- SSC CGL Previous Year Question Paper

- SSC CGL Admit Card 2024

- SSC MTS 2024

- SSC MTS Apply Online 2024

- SSC MTS Syllabus 2024

- SSC MTS Salary 2024

- SSC MTS Eligibility Criteria 2024

- SSC MTS Previous Year Paper

SSC Stenographer 2024

- SSC Stenographer Notification 2024

- SSC Stenographer Apply Online 2024

- SSC Stenographer Syllabus 2024

- SSC Stenographer Salary 2024

- SSC Stenographer Eligibility Criteria 2024

SSC GD Constable 2025

- SSC GD Salary 2025

- SSC GD Constable Syllabus 2025

- SSC GD Eligibility Criteria 2025

IMPORTANT EXAMS

- Terms & Conditions

- Return & Refund Policy

- Privacy Policy

- UPSC IAS Exam Pattern

- UPSC IAS Prelims

- UPSC IAS Mains

- UPSC IAS Interview

- UPSC IAS Optionals

- UPSC Notification

- UPSC Eligibility Criteria

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Admit Card

- UPSC Results

- UPSC Cut-Off

- UPSC Calendar

- Documents Required for UPSC IAS Exam

- UPSC IAS Prelims Syllabus

- General Studies 1

- General Studies 2

- General Studies 3

- General Studies 4

- UPSC IAS Interview Syllabus

- UPSC IAS Optional Syllabus

Carnatic Music – UPSC Art & Culture Notes

Carnatic music, a rich and intricate musical tradition, finds its home in the southern regions of India, particularly in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. Rooted in ancient traditions and boasting a highly developed theoretical system, Carnatic music is a testament to the profound cultural and musical heritage of South India. This article delves into the captivating world of Carnatic music, exploring its historical development, key elements, and unique compositions.

Table of Contents

The Theoretical Foundations

At the heart of Carnatic music lies a complex theoretical framework built upon two essential components: Ragam (Raga) and Thalam (Tala). Ragam represents the melodic structure and scale, while Thalam governs the rhythmic framework of a composition. These elements provide the foundation upon which Carnatic music builds its intricate melodies and rhythms.

Key Figures in the Development of Carnatic Music

Purandaradasa (1480-1564) is often regarded as the father of Carnatic music. He played a pivotal role in codifying the methods and rules of Carnatic music, leaving behind a legacy of several thousand compositions. Another luminary in the world of Carnatic music is Venkat Mukhi Swami, who is celebrated as the grand theorist of this art form. He made significant contributions, including the development of “Melankara,” a system for classifying South Indian ragas.

The Trinity of Carnatic Music