The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

- 2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- 3 Université de Paris, Centre of Epidemiology and Statistics (CRESS), Inserm, Paris, France.

- 4 Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia.

- 5 University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, United States of America; Annals of Internal Medicine.

- 6 Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, Toronto, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

- 7 Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada.

- 8 Clinical Research Institute, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

- 9 Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, United States of America.

- 10 York Health Economics Consortium (YHEC Ltd), University of York, York, United Kingdom.

- 11 Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

- 12 Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Odense (CEBMO) and Cochrane Denmark, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Open Patient data Exploratory Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark.

- 13 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada; Clinical Epidemiology Program, Blueprint Translational Research Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; Regenerative Medicine Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada.

- 14 Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, United States; Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America.

- 15 Division of Headache, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Head of Research, The BMJ, London, United Kingdom.

- 16 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Indiana University School of Public Health-Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, United States of America.

- 17 Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom.

- 18 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, United Kingdom.

- 19 EPPI-Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London, London, United Kingdom.

- 20 Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Epidemiology Division of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and the Institute of Health Management, Policy, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Queen's Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada.

- 21 Methods Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

- 22 Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

- PMID: 33780438

- PMCID: PMC8007028

- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

Matthew Page and co-authors describe PRISMA 2020, an updated reporting guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Publication types

- Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Evidence-Based Medicine / standards*

- Publishing / standards*

- Systematic Reviews as Topic* / methods

- Systematic Reviews as Topic* / standards

Grants and funding

- UG1 EY020522/EY/NEI NIH HHS/United States

- DRF-2018-11-ST2-048/DH_/Department of Health/United Kingdom

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Academic Process

- Creating a PRISMA flow diagram

- PRISMA 2020

Creating a PRISMA flow diagram: PRISMA 2020

Created by health science librarians.

What is PRISMA?

Which prisma 2020 flow diagram should i use, step-by-step: prisma 2020 flow diagram, using the covidence prisma diagram, documenting your grey literature search, updating a systematic review with prisma 2020, citing prisma 2020, for more information, prisma 2020 checklist.

- PRISMA 2020 Checklist (.doc)

- PRISMA 2020 Checklist (.pdf)

- PRISMA 2020 Expanded Checklist

PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram Templates

- PRISMA 2020 V1- New Reviews with Databases and Registers only PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only

- PRISMA 2020 V2 - New Reviews with Databases, Registers, and Other Sources PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources

The format of the PRISMA Step-By-Step was first developed by Glasgow Caledonian University https://www.gcu.ac.uk/library

"PRISMA stands for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

It is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

The aim of the PRISMA Statement is to help authors improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We have focused on randomized trials, but PRISMA can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews of other types of research, particularly evaluations of interventions. PRISMA may also be useful for critical appraisal of published systematic reviews, although it is not a quality assessment instrument to gauge the quality of a systematic review. The PRISMA Statement consists of a 27-item checklist and a four-phase flow diagram ."

"The PRISMA Explanation and Elaboration document explains and illustrates the principles underlying the PRISMA Statement. It is strongly recommended that it be used in conjunction with the PRISMA Statement.

PRISMA is part of a broader effort, to improve the reporting of different types of health research, and in turn to improve the quality of research used in decision-making in healthcare."

From prisma-statement.org

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol . 2009;62(10):e1-e34. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt P, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. doi:10.31222/osf.io/gwdhk.

Rethlefsen M, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, et al. PRISMA-S: An Extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. doi:10.31219/osf.io/sfc38.

In PRISMA 2020, there are now expanded options depending on where you search and whether you are updating a review. Version 1 of PRISMA 2020 includes databases and clinical trial or preprint registers. Version 2 includes additional sections for elaborating on your grey literature search, such as searches on websites or in citation lists. Both versions are available for new and updated reviews from the Equator Network's PRISMA Flow Diagram page .

Templates for New Reviews

Step 1: Preparation To complete the the PRISMA diagram, save a copy of the diagram to use alongside your searches. It can be downloaded from the PRISMA website .

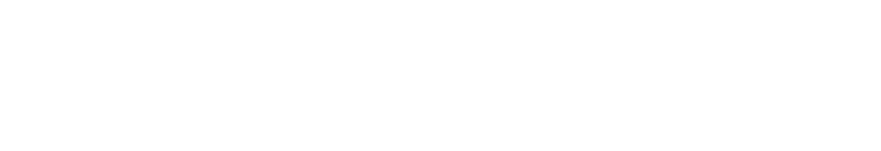

Step 2: Doing the Database Search Run the search for each database individually, including ALL your search terms, any MeSH or other subject headings, truncation (like hemipleg * ), and/or wildcards (like sul ? ur). Apply all your limits (such as years of search, English language only, and so on). Once all search terms have been combined and you have applied all relevant limits, you should have a final number of records or articles for each database. Enter this information in the top left box of the PRISMA flow chart. You should add the total number of combined results from all databases (including duplicates) after the equal sign where it says Databases (n=) . Many researchers also add notations in the box for the number of results from each database search, for example, Pubmed (n=335), Embase (n= 600), and so on. If you search trial registers, such as ClinicalTrials.gov , CENTRAL , ICTRP , or others, you should enter that number after the equal sign in Registers (n=) .

NOTE: Some citation managers automatically remove duplicates with each file you import. Be sure to capture the number of articles from your database searches before any duplicates are removed.

Step 3: Remove All Duplicates To avoid reviewing duplicate articles, you need to remove any articles that appear more than once in your results. You may want to export the entire list of articles from each database to a citation manager such as EndNote, Sciwheel, Zotero, or Mendeley (including both citation and abstract in your file) and remove the duplicates there. If you are using Covidence for your review, you should also add the duplicate articles identified in Covidence to the citation manager number. Enter the number of records removed as duplicates in the second box on your PRISMA template. If you are using automation tools to help evaluate the relevance of citations in your results, you would also enter that number here.

NOTE: If you are using Covidence to screen your articles , you can copy the numbers from the PRISMA diagram in your Covidence review into the boxes mentioned below. Covidence does not include the number of results from each database, so you will need to keep track of that number yourself.

Step 4: Records Screened- Title/Abstract Screening The next step is to add the number of articles that you will screen. This should be the number of records identified minus the number from the duplicates removed box.

Step 5: Records Excluded- Title/Abstract Screening You will need to screen the titles and abstracts for articles which are relevant to your research question. Any articles that appear to help you provide an answer to your research question should be included. Record the number of articles excluded through title/abstract screening in the box to the right titled "Records excluded." You can optionally add exclusion reasons at this level, but they are not required until full text screening.

Step 6: Reports Sought for Retrieval This is the number of articles you obtain in preparation for full text screening. Subtract the number of excluded records (Step 5) from the total number screened (Step 4) and this will be your number sought for retrieval.

Step 7: Reports Not Retrieved List the number of articles for which you are unable to find the full text. Remember to use Find@UNC and Interlibrary Loan to request articles to see if we can order them from other libraries before automatically excluding them.

Step 8: Reports Assessed for Eligibility- Full Text Screening This should be the number of reports sought for retrieval (Step 6) minus the number of reports not retrieved (Step 7). Review the full text for these articles to assess their eligibility for inclusion in your systematic review.

Step 9: Reports Excluded After reviewing all articles in the full-text screening stage for eligibility, enter the total number of articles you exclude in the box titled "Reports excluded," and then list your reasons for excluding the articles as well as the number of records excluded for each reason. Examples include wrong setting, wrong patient population, wrong intervention, wrong dosage, etc. You should only count an excluded article once in your list even if if meets multiple exclusion criteria.

Step 10: Included Studies The final step is to subtract the number of records excluded during the eligibility review of full-texts (Step 9) from the total number of articles reviewed for eligibility (Step 8). Enter this number in the box labeled "Studies included in review," combining numbers with your grey literature search results in this box if needed. You have now completed your PRISMA flow diagram, unless you have also performed searches in non-database sources.

To view the PRISMA diagram created after using Covidence to screen references for your review, click the PRISMA button on the main menu of your review in Covidence.

If you listed your sources when importing citations, your PRISMA diagram will include the list of databases you used and the number of references from each.

If you imported references from a citation manager, your PRISMA diagram starts with duplicate removal. To have a complete PRISMA diagram, you will need to add the number of results from each database you searched, as well as the number of additional sources you found.

Once you have finished title/abstract and full text screening (and data extraction or quality assessment if applicable), click Download DOCX to download your flow diagram as a Word document, or click View as text to copy and paste the PRISMA data or into an editable template for PRISMA and fill in the numbers.

There are many places articles can get lost in the review process. Remember to make sure your PRISMA numbers add up correctly!

Step 6: Included Studies The final step is to subtract the number of excluded articles or records during the eligibility review of full-texts from the total number of articles reviewed for eligibility. Enter this number in the box labeled "Studies included in review," combining numbers with your database search results in this box if needed. You have now completed your PRISMA flow diagram, which you can now include in the results section of your article or assignment.

If you are updating an existing review, use one of these PRISMA 2020 Updated Review templates, which feature an additional box for the number of studies and reports of studies included in the previous search iterations.

- PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews- databases and registers only

- PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews- databases, registers and other sources

When referring to PRISMA 2020, The Equator Network recommends using journal article citations (such as those in our For More Information box ) rather than referring to the PRISMA website. If you are not already using a journal article citation, they recommend that you cite one of the original publications of the PRISMA Statement or PRISMA Explanation and Elaboration .

Related HSL Guides

- Systematic Reviews

Additional Readings

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement . J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103-112.

- Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews . Bmj. 2021;372:n160.

- Radua J. PRISMA 2020 - An updated checklist for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;124:324-325.

- Sarkis-Onofre R, Catalá-López F, Aromataris E, Lockwood C. How to properly use the PRISMA Statement . Systematic reviews. 2021;10(1):117-117.

- Sohrabi C, Franchi T, Mathew G, et al. PRISMA 2020 statement: What's new and the importance of reporting guidelines. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105918.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews . Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews . Bmj. 2021;372:n71.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews . PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews . Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89.

- Last Updated: Mar 12, 2024 8:53 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/prisma

Search & Find

- E-Research by Discipline

- More Search & Find

Places & Spaces

- Places to Study

- Book a Study Room

- Printers, Scanners, & Computers

- More Places & Spaces

- Borrowing & Circulation

- Request a Title for Purchase

- Schedule Instruction Session

- More Services

Support & Guides

- Course Reserves

- Research Guides

- Citing & Writing

- More Support & Guides

- Mission Statement

- Diversity Statement

- Staff Directory

- Job Opportunities

- Give to the Libraries

- News & Exhibits

- Reckoning Initiative

- More About Us

- Search This Site

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

- Give Us Your Feedback

- 208 Raleigh Street CB #3916

- Chapel Hill, NC 27515-8890

- 919-962-1053

- Open access

- Published: 19 April 2021

How to properly use the PRISMA Statement

- Rafael Sarkis-Onofre 1 ,

- Ferrán Catalá-López 2 , 3 ,

- Edoardo Aromataris 4 &

- Craig Lockwood 4

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 117 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

64k Accesses

171 Citations

103 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Research to this article was published on 29 March 2021

It has been more than a decade since the original publication of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [ 1 ], and it has become one of the most cited reporting guidelines in biomedical literature [ 2 , 3 ]. Since its publication, multiple extensions of the PRISMA Statement have been published concomitant with the advancement of knowledge synthesis methods [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The PRISMA2020 statement, an updated version has recently been published [ 8 ], and other extensions are currently in development [ 9 ].

The number of systematic reviews (SRs) has increased substantially over the past 20 years [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. However, many SRs continue to be poorly conducted and reported [ 10 , 11 ], and it is still common to see articles that use the PRISMA Statement and other reporting guidelines inappropriately, as was highlighted recently [ 13 ].

The PRISMA Statement and its extensions are an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations designed primarily to encourage transparent and complete reporting of SRs. This growing set of guidelines have been developed to aid authors with appropriate reporting of different knowledge synthesis methods (such as SRs, scoping reviews, and review protocols) and to ensure that all aspects of this type of research are accurately and transparently reported. In other words, the PRISMA Statement is a road map to help authors best describe what was done, what was found, and in the case of a review protocol, what are they are planning to do.

Despite this clear and well-articulated intention [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ], it is common for Systematic Reviews to receive manuscripts detailing the inappropriate use of the PRISMA Statement and its extensions. Most frequently, improper use appears with authors attempting to use the PRISMA statement as a methodological guideline for the design and conduct reviews, or identifying the PRISMA statement as a tool to assess the methodological quality of reviews, as seen in the following examples:

“This scoping review will be conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Statement.”

“This protocol was designed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) Statement.”

“The methodological quality of the included systematic reviews will be assessed with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.”

Some organizations (such as Cochrane and JBI) have developed methodological guidelines that can help authors to design or conduct diverse types of knowledge synthesis rigorously [ 14 , 15 ]. While the PRISMA statement is presented to predominantly guide reporting of a systematic review of interventions with meta-analyses, its detailed criteria can readily be applied to the majority of review types [ 13 ]. Differences between the role of the PRISMA Statement to guide reporting versus guidelines detailing methodological conduct is readily illustrated with the following example: the PRISMA Statement recommends that authors report their complete search strategies for all databases, registers, and websites (including any filters and limits used), but it does not include recommendations for designing and conducting literature searches [ 8 ]. If authors are interested in understanding how to create search strategies or which databases to include, they should refer to the methodological guidelines [ 12 , 13 ]. Thus, the following examples can illustrate the appropriate use of the PRISMA Statement in research reporting:

“The reporting of this systematic review was guided by the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement.”

“This scoping review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).”

“The protocol is being reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) Statement.”

Systematic Reviews supports the complete and transparent reporting of research. The Editors require the submission of a populated checklist from the relevant reporting guidelines, including the PRISMA checklist or the most appropriate PRISMA extension. Using the PRISMA statement and its extensions to write protocols or the completed review report, and completing the PRISMA checklists are likely to let reviewers and readers know what authors did and found, but also to optimize the quality of reporting and make the peer review process more efficient.

Transparent and complete reporting is an essential component of “good research”; it allows readers to judge key issues regarding the conduct of research and its trustworthiness and is also critical to establish a study’s replicability.

With the release of a major update to PRISMA in 2021, the appropriate use of the updated PRISMA Statement (and its extensions as those updates progress) will be an essential requirement for review based submissions, and we encourage authors, peer reviewers, and readers of Systematic Reviews to use and disseminate that initiative.

Availability of data and materials

We do not have any additional data or materials to share.

Abbreviations

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols

Systematic reviews

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Caulley L, Cheng W, Catala-Lopez F, Whelan J, Khoury M, Ferraro J, et al. Citation impact was highly variable for reporting guidelines of health research: a citation analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;127:96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.07.013 .

Page MJ, Moher D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and extensions: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0663-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z .

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 .

Article Google Scholar

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 .

Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777–84. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2385 .

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. https://doi/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4.

EQUATOR Network: Reporting guidelines under development for systematic reviews. https://www.equator-network.org/library/reporting-guidelines-under-development/reporting-guidelines-under-development-for-systematic-reviews/ . Accessed 11 Feb 2021.

Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Sampson M, Tricco AC, et al. Epidemiology and Reporting Characteristics of Systematic Reviews of Biomedical Research: A Cross-Sectional Study. Plos Med. 2016;13(5):e1002028. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002028 .

Ioannidis JP. The Mass Production of Redundant, Misleading, and Conflicted Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016;94(3):485–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12210 .

Niforatos JD, Weaver M, Johansen ME. Assessment of Publication Trends of Systematic Reviews and Randomized Clinical Trials, 1995 to 2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1593–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3013.

Caulley L, Catala-Lopez F, Whelan J, Khoury M, Ferraro J, Cheng W, et al. Reporting guidelines of health research studies are frequently used inappropriately. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;122:87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.006 .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2019.

Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. ed. Adelaide: JBI; 2020.

Download references

Acknowledgements

RSO is funded in part by Meridional Foundation. FCL is funded in part by the Institute of Health Carlos III/CIBERSAM.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Graduate Program in Dentistry, Meridional Faculty, IMED, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Rafael Sarkis-Onofre

Department of Health Planning and Economics, National School of Public Health, Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain

Ferrán Catalá-López

Department of Medicine, University of Valencia/INCLIVA Health Research Institute and CIBERSAM, Valencia, Spain

JBI, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia

Edoardo Aromataris & Craig Lockwood

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RSO drafted the initial version. FCL, EA, and CL made substantial additions to the first and subsequent drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rafael Sarkis-Onofre .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

CL is Editor-in-Chief of Systematic Reviews, FCL is Protocol Editor of Systematic Reviews, and RSO is Associate Editor of Systematic Reviews.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sarkis-Onofre, R., Catalá-López, F., Aromataris, E. et al. How to properly use the PRISMA Statement. Syst Rev 10 , 117 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01671-z

Download citation

Published : 19 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01671-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Med Libr Assoc

- v.110(2); 2022 Apr 1

PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S: common questions on tracking records and the flow diagram

Melissa l. rethlefsen.

1 moc.liamg@nesfelhterlm , Executive Director and Professor, Health Sciences Library & Informatics Center, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

Matthew J. Page

2 [email protected] , Senior Research Fellow and ARC DECRA Fellow, Methods in Evidence Synthesis Unit, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

The PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S guidelines help systematic review teams report their reviews clearly, transparently, and with sufficient detail to enable reproducibility. PRISMA 2020, an updated version of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement, is complemented by PRISMA-S, an extension to PRISMA focusing on reporting the search components of systematic reviews. Several significant changes were implemented in PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S when compared with the original version of PRISMA in 2009, including the recommendation to report search strategies for all databases, registries, and websites that were searched. PRISMA-S also recommends reporting the number of records identified from each information source. One of the most challenging aspects of the new guidance from both documents has been changes to the flow diagram. In this article, we review some of the common questions about using the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram and tracking records through the systematic review process.

In early 2021, two reporting guidelines were released that provide direct guidance on how to report the literature search components of systematic reviews and related review types: PRISMA 2020, the updated version of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [ 1 , 2 ]; and PRISMA-S, an extension to PRISMA focused solely on reporting the search components of systematic reviews [ 3 ]. PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S include several significant changes from the original version of PRISMA published in 2009 [ 4 ], including the recommendation to report search strategies for all databases, registries, and websites that were searched.

One of the most challenging aspects of integrating the new guidance from both documents into practice has been changes to the PRISMA flow diagram, which tracks the flow of information through the systematic review process. In the original version, the flow diagram was broken into four sections: identification, screening, eligibility, and included [ 4 ]. The identification section included boxes for recording the number of records identified through database searching, the number of records identified through other sources, and the number of records after deduplication. Often, using the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram, the “records identified through other sources” box contained only the number of records matching inclusion criteria, not necessarily all the records identified and screened. Building upon the original PRISMA 2009 flow diagram, PRISMA-S recommends constructing the flow diagram to show the number of records retrieved per database in the “records identified through database searching” box. Additionally, PRISMA-S asks authors to record the number of records retrieved for each other information source in the “records identified through other sources” box [ 3 ]. PRISMA-S also suggests reporting the total number of references retrieved from all sources, including updates, in the results section and the total number of references from each database and information source in the supplementary materials.

With the new PRISMA 2020 flow diagram template, systematic review teams now have the opportunity to better represent the complexity of the search process [ 1 ]. There are now four templates available, including flow diagram templates designed specifically for updates and systematic reviews that search beyond databases and study registries [ 5 ]. Generally, most systematic review teams will use the “PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources” (see Figure 1 for an example) [ 5 ]. In this flow diagram, records are tracked through two different columns: identification of studies via databases and registers (Column 1) and identification of studies via other methods (Column 2). The flow diagram itself provides guidance on what type of information resource should be reported in which column, specifically noting that records identified from websites, organizations, citation searching, and other methods should be reported in Column 2. The flow diagram template also suggests reporting an overall number for records identified from databases and registers in Column 1.

Example of a “PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources” made using the R ShinyApp [ 1 , 6 , 7 ]

In the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram, Column 2 represents the “Additional records identified through other sources” from the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram but with major improvements to enhance tracking the entire flow of information through the systematic review process. Using the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram, many researchers only put the total number of records that met inclusion criteria in the “Additional records” box, thus excluding the total number of records that were retrieved from each source. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram makes it explicit that it is expected that the total number of records retrieved from each information source should be tracked, which aligns with PRISMA-S's guidelines.

Since the publication of PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S, researchers have posed many questions about the best ways to track records and use the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram appropriately. In the rest of this commentary, we will answer some of the most common ones.

All four versions of the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram are available in Word format on the PRISMA website [ 5 ]. In addition, there is a very useful R ShinyApp that creates downloadable flow diagrams from inputted data [ 6 , 7 ].

Do I need to seek permission from the authors to include a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram in my systematic review manuscript?

No, permission is not required. The PRISMA 2020 papers that include the flow diagram templates were published as open access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work, even for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

PRISMA-S was released slightly before PRISMA 2020, so the styles do not entirely align, but they are compatible—with a few tweaks. In PRISMA-S, the flow diagram example shows study registries data in the “Additional records identified through other sources” box (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov ) [ 3 ]. In the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram, Column 1 contains all data related to records and studies identified in study registries, and Column 2 now contains all records identified outside of databases and study registries, such as websites, reference lists, and contacts with manufacturers, among others [ 1 ].

PRISMA-S does recommend that, if space is available, individual databases and other information sources' identified records should be included in the flow diagram. This is not currently possible to do using the R ShinyApp [ 6 ], but any of the Word templates can be modified to add this information [ 5 ]. If it is not possible, the number of records per individual information source should go in the supplementary materials.

It may be helpful to put all citation searching results in Column 2 and reserve Column 1 for reporting subject-based searching, but it is not necessary to do so; users are free to modify the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram templates in a way they consider most optimal for their review. Citation indexes are indeed databases and can be included in Column 1, particularly if the records are assessed as part of the primary screening process [ 2 ]. As with all other searches, researchers conducting citation searches for citing or cited references should report the number of records identified per search in the supplementary materials. It is also important to cite each “base” article examined for citing or cited references in the manuscript text for reproducibility and transparency [ 3 ].

Identifying records and studies from other methods and information sources is one of the trickiest components of a systematic review to report. As acknowledged by the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram, those components of the review often take place outside the “normal” flow of screening that happens during the systematic review process. The ability (or lack thereof) to track the initial number of records identified is often determined by the process used to identify and screen the records—and the system used to manage records identified from other information sources. When records are all centrally tracked, regardless of source, it is easier to produce this data.

Best practice is to count all records identified (by hand or by other means) from each source. This information should be reported individually in supplementary materials, according to PRISMA-S [ 3 ]. It should also be reported in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [ 5 ], either by individual information source or by category of information source (i.e., all records identified from websites). If it is not possible or feasible to count all records, report what is feasible.

Google Scholar is both a database and a citation index, and systematic review teams often use Google Scholar for both reasons. For subject-based searching, Google Scholar is considered as a database for the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram and can be reported in Column 1. If Google Scholar is only used as a citation index, data can be reported in either Column 1 or Column 2. The number of records identified should be reported per search in the supplementary materials, per PRISMA-S. If a systematic review team searches Google Scholar as both a traditional bibliographic database and as a citation index, the team may wish to use both Column 1 (subject-based search) and Column 2 (citation searching), but it is also reasonable to combine them in Column 1 in the flow diagram. Each search, however, needs to be reported separately in the supplementary materials.

Google, on the other hand, is not a traditional bibliographic database nor a citation index. It should be considered as an additional information source and reported in Column 2.

A complication of both Google and Google Scholar is that a maximum of 1,000 records is available for any given search, including citation searches [ 3 ]. Therefore, the total number of records identified from these two sources should never be listed in the flow diagram as above 1,000 for any given search. Many times, review teams will pre-identify how many records in Google or Google Scholar they will review per search; this should be the number reported for each search, unless the true number of results identified from a search is smaller.

Yes. Though it is quite convenient to have that detail in the flow diagram, it is not essential to present it there. The number of records identified for each individual database and information source should be reported, however, in the supplementary materials regardless of whether they are included in the flow diagram. If a research team or publication prefers to report these records and sources in both places, the Word templates for the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram are customizable [ 5 ]. The R ShinyApp development team is also actively considering improvements so this feature may be available in future versions [ 6 , 7 ].

PRISMA-S treats all results from the same search, regardless of whether it was the original search or an update, as a single data point [ 3 ]. In the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram, report the total number of items retrieved per database across the lifespan of the systematic review searching process [ 5 ]. If multiple separate searches occurred for a particular database, the total results from each search can be combined in the flow diagram. Authors can consider reporting the number of records retrieved at each search point, original plus update(s), in the supplementary materials.

There are occasions where reports cannot be located, for a multitude of reasons. This may include a journal that cannot be accessed in a local collection or via interlibrary loan, lack of response from authors or contacts, or broken links. Use the appropriate column's “Reports not retrieved” box to indicate how many reports were not able to be retrieved, regardless of reason.

On some occasions, authors might identify a study that has results appearing in two reports (one providing data at three months, another at two years follow-up). In this case, the number of studies included in the review is one, whereas the number of reports of included studies is two. This distinction was introduced in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram based on our observation that the jump from the number of reports assessed for eligibility to the number of studies included in the review (as was prompted in the original PRISMA flow diagram) sometimes resulted in some reports not being accounted for [ 2 ]. For example, we have seen some flow diagrams where the authors report assessing fifty full-text reports for eligibility, excluding forty reports , and including eight studies (failing to indicate that two of the eight studies were published in two reports).

Loading metrics

Open Access

Guidelines and Guidance

The Guidelines and Guidance section contains advice on conducting and reporting medical research.

See all article types »

The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

Affiliation Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Affiliation Université de Paris, Centre of Epidemiology and Statistics (CRESS), Inserm, Paris, France

Affiliation Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia

Affiliation University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, United States of America; Annals of Internal Medicine

Affiliation Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, Toronto, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Affiliation Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada

Affiliation Clinical Research Institute, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Affiliation Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, United States of America

Affiliation York Health Economics Consortium (YHEC Ltd), University of York, York, United Kingdom

Affiliation Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Affiliation Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Odense (CEBMO) and Cochrane Denmark, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Open Patient data Exploratory Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

Affiliation Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada; Clinical Epidemiology Program, Blueprint Translational Research Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; Regenerative Medicine Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

Affiliation Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, United States; Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Affiliation Division of Headache, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Head of Research, The BMJ, London, United Kingdom

Affiliation Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Indiana University School of Public Health-Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, United States of America

Affiliation Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

Affiliation Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, United Kingdom

Affiliation EPPI-Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Affiliation Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Epidemiology Division of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and the Institute of Health Management, Policy, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Queen’s Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

Affiliation Methods Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- [ ... ],

Affiliation Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- [ view all ]

- [ view less ]

- Matthew J. Page,

- Joanne E. McKenzie,

- Patrick M. Bossuyt,

- Isabelle Boutron,

- Tammy C. Hoffmann,

- Cynthia D. Mulrow,

- Larissa Shamseer,

- Jennifer M. Tetzlaff,

- Elie A. Akl,

Published: March 29, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

- Reader Comments

Citation: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med 18(3): e1003583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

Copyright: © 2021 Page et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: There was no direct funding for this research. MJP is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE200101618) and was previously supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (1088535) during the conduct of this research. JEM is supported by an Australian NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1143429). TCH is supported by an Australian NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1154607). JMT is supported by Evidence Partners Inc. JMG is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Health Knowledge Transfer and Uptake. MML is supported by The Ottawa Hospital Anaesthesia Alternate Funds Association and a Faculty of Medicine Junior Research Chair. TL is supported by funding from the National Eye Institute (UG1EY020522), National Institutes of Health, United States. LAM is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Doctoral Research Fellowship (DRF-2018-11-ST2-048). ACT is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. DM is supported in part by a University Research Chair, University of Ottawa. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: I have read the journal’s policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: EL is head of research for the BMJ; MJP is an editorial board member for PLOS Medicine; ACT is an associate editor and MJP, TL, EMW, and DM are editorial board members for the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology; DM and LAS were editors in chief, LS, JMT, and ACT are associate editors, and JG is an editorial board member for Systematic Reviews. None of these authors were involved in the peer review process or decision to publish. TCH has received personal fees from Elsevier outside the submitted work. EMW has received personal fees from the American Journal for Public Health, for which he is the editor for systematic reviews. VW is editor in chief of the Campbell Collaboration, which produces systematic reviews, and co-convenor of the Campbell and Cochrane equity methods group. DM is chair of the EQUATOR Network, IB is adjunct director of the French EQUATOR Centre and TCH is co-director of the Australasian EQUATOR Centre, which advocates for the use of reporting guidelines to improve the quality of reporting in research articles. JMT received salary from Evidence Partners, creator of DistillerSR software for systematic reviews; Evidence Partners was not involved in the design or outcomes of the statement, and the views expressed solely represent those of the author.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, published in 2009, was designed to help systematic reviewers transparently report why the review was done, what the authors did, and what they found. Over the past decade, advances in systematic review methodology and terminology have necessitated an update to the guideline. The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies. The structure and presentation of the items have been modified to facilitate implementation. In this article, we present the PRISMA 2020 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and the revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews .

Systematic reviews serve many critical roles. They can provide syntheses of the state of knowledge in a field, from which future research priorities can be identified; they can address questions that otherwise could not be answered by individual studies; they can identify problems in primary research that should be rectified in future studies; and they can generate or evaluate theories about how or why phenomena occur. Systematic reviews therefore generate various types of knowledge for different users of reviews (such as patients, healthcare providers, researchers, and policy makers).[ 1 , 2 ]To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did (such as how studies were identified and selected) and what they found (such as characteristics of contributing studies and results of meta-analyses). Up-to-date reporting guidance facilitates authors achieving this.[ 3 ]

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement published in 2009 (hereafter referred to as PRISMA 2009)[ 4 – 10 ] is a reporting guideline designed to address poor reporting of systematic reviews.[ 11 ] The PRISMA 2009 statement comprised a checklist of 27 items recommended for reporting in systematic reviews and an “explanation and elaboration” paper[ 12 – 16 ] providing additional reporting guidance for each item, along with exemplars of reporting. The recommendations have been widely endorsed and adopted, as evidenced by its co-publication in multiple journals, citation in over 60 000 reports (Scopus, August 2020), endorsement from almost 200 journals and systematic review organisations, and adoption in various disciplines. Evidence from observational studies suggests that use of the PRISMA 2009 statement is associated with more complete reporting of systematic reviews,[ 17 – 20 ] although more could be done to improve adherence to the guideline.[ 21 ]

Many innovations in the conduct of systematic reviews have occurred since publication of the PRISMA 2009 statement. For example, technological advances have enabled the use of natural language processing and machine learning to identify relevant evidence,[ 22 – 24 ] methods have been proposed to synthesise and present findings when meta-analysis is not possible or appropriate,[ 25 – 27 ] and new methods have been developed to assess the risk of bias in results of included studies.[ 28 , 29 ] Evidence on sources of bias in systematic reviews has accrued, culminating in the development of new tools to appraise the conduct of systematic reviews.[ 30 , 31 ] Terminology used to describe particular review processes has also evolved, as in the shift from assessing “quality” to assessing “certainty” in the body of evidence.[ 32 ] In addition, the publishing landscape has transformed, with multiple avenues now available for registering and disseminating systematic review protocols,[ 33 , 34 ] disseminating reports of systematic reviews, and sharing data and materials, such as preprint servers and publicly accessible repositories. To capture these advances in the reporting of systematic reviews necessitated an update to the PRISMA 2009 statement.

Summary points

- To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did, and what they found

- The PRISMA 2020 statement provides updated reporting guidance for systematic reviews that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies

- The PRISMA 2020 statement consists of a 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews

- We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders

Development of PRISMA 2020

A complete description of the methods used to develop PRISMA 2020 is available elsewhere.[ 35 ] We identified PRISMA 2009 items that were often reported incompletely by examining the results of studies investigating the transparency of reporting of published reviews.[ 17 , 21 , 36 , 37 ] We identified possible modifications to the PRISMA 2009 statement by reviewing 60 documents providing reporting guidance for systematic reviews (including reporting guidelines, handbooks, tools, and meta-research studies).[ 38 ] These reviews of the literature were used to inform the content of a survey with suggested possible modifications to the 27 items in PRISMA 2009 and possible additional items. Respondents were asked whether they believed we should keep each PRISMA 2009 item as is, modify it, or remove it, and whether we should add each additional item. Systematic review methodologists and journal editors were invited to complete the online survey (110 of 220 invited responded). We discussed proposed content and wording of the PRISMA 2020 statement, as informed by the review and survey results, at a 21-member, two-day, in-person meeting in September 2018 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Throughout 2019 and 2020, we circulated an initial draft and five revisions of the checklist and explanation and elaboration paper to co-authors for feedback. In April 2020, we invited 22 systematic reviewers who had expressed interest in providing feedback on the PRISMA 2020 checklist to share their views (via an online survey) on the layout and terminology used in a preliminary version of the checklist. Feedback was received from 15 individuals and considered by the first author, and any revisions deemed necessary were incorporated before the final version was approved and endorsed by all co-authors.

The PRISMA 2020 statement

Scope of the guideline.

The PRISMA 2020 statement has been designed primarily for systematic reviews of studies that evaluate the effects of health interventions, irrespective of the design of the included studies. However, the checklist items are applicable to reports of systematic reviews evaluating other interventions (such as social or educational interventions), and many items are applicable to systematic reviews with objectives other than evaluating interventions (such as evaluating aetiology, prevalence, or prognosis). PRISMA 2020 is intended for use in systematic reviews that include synthesis (such as pairwise meta-analysis or other statistical synthesis methods) or do not include synthesis (for example, because only one eligible study is identified). The PRISMA 2020 items are relevant for mixed-methods systematic reviews (which include quantitative and qualitative studies), but reporting guidelines addressing the presentation and synthesis of qualitative data should also be consulted.[ 39 , 40 ] PRISMA 2020 can be used for original systematic reviews, updated systematic reviews, or continually updated (“living”) systematic reviews. However, for updated and living systematic reviews, there may be some additional considerations that need to be addressed. Where there is relevant content from other reporting guidelines, we reference these guidelines within the items in the explanation and elaboration paper [ 41 ] (such as PRISMA-Search [ 42 ] in items 6 and 7, Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline [ 27 ] in item 13d). Box 1 includes a glossary of terms used throughout the PRISMA 2020 statement.

Box 1. Glossary of terms

- Systematic review —A review that uses explicit, systematic methods to collate and synthesise findings of studies that address a clearly formulated question [ 43 ]

- Statistical synthesis —The combination of quantitative results of two or more studies. This encompasses meta-analysis of effect estimates (described below) and other methods, such as combining P values, calculating the range and distribution of observed effects, and vote counting based on the direction of effect (see McKenzie and Brennan [ 25 ] for a description of each method)

- Meta-analysis of effect estimates —A statistical technique used to synthesise results when study effect estimates and their variances are available, yielding a quantitative summary of results [ 25 ]

- Outcome —An event or measurement collected for participants in a study (such as quality of life, mortality)

- Result —The combination of a point estimate (such as a mean difference, risk ratio, or proportion) and a measure of its precision (such as a confidence/credible interval) for a particular outcome

- Report —A document (paper or electronic) supplying information about a particular study. It could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report, or any other document providing relevant information

- Record —The title or abstract (or both) of a report indexed in a database or website (such as a title or abstract for an article indexed in Medline). Records that refer to the same report (such as the same journal article) are “duplicates”; however, records that refer to reports that are merely similar (such as a similar abstract submitted to two different conferences) should be considered unique.

- Study —An investigation, such as a clinical trial, that includes a defined group of participants and one or more interventions and outcomes. A “study” might have multiple reports. For example, reports could include the protocol, statistical analysis plan, baseline characteristics, results for the primary outcome, results for harms, results for secondary outcomes, and results for additional mediator and moderator analyses

PRISMA 2020 is not intended to guide systematic review conduct, for which comprehensive resources are available.[ 43 – 46 ] However, familiarity with PRISMA 2020 is useful when planning and conducting systematic reviews to ensure that all recommended information is captured. PRISMA 2020 should not be used to assess the conduct or methodological quality of systematic reviews; other tools exist for this purpose.[ 30 , 31 ] Furthermore, PRISMA 2020 is not intended to inform the reporting of systematic review protocols, for which a separate statement is available (PRISMA for Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement [ 47 , 48 ]). Finally, extensions to the PRISMA 2009 statement have been developed to guide reporting of network meta-analyses,[ 49 ] meta-analyses of individual participant data,[ 50 ] systematic reviews of harms, [ 51 ] systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies, [ 52 ] and scoping reviews [ 53 ]; for these types of reviews we recommend authors report their review in accordance with the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 along with the guidance specific to the extension.

How to use PRISMA 2020

The PRISMA 2020 statement (including the checklists, explanation and elaboration, and flow diagram) replaces the PRISMA 2009 statement, which should no longer be used. Box 2 summarises noteworthy changes from the PRISMA 2009 statement. The PRISMA 2020 checklist includes seven sections with 27 items, some of which include sub-items ( Table 1 ). A checklist for journal and conference abstracts for systematic reviews is included in PRISMA 2020. This abstract checklist is an update of the 2013 PRISMA for Abstracts statement,[ 54 ] reflecting new and modified content in PRISMA 2020 ( Table 2 ). A template PRISMA flow diagram is provided, which can be modified depending on whether the systematic review is original or updated ( Fig 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

The new design is adapted from flow diagrams proposed by Boers,[ 55 ] Mayo-Wilson et al.[ 56 ] and Stovold et al.[ 57 ] The boxes in grey should only be completed if applicable; otherwise they should be removed from the flow diagram. Note that a “report” could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report or any other document providing relevant information.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583.t002

Box 2. Noteworthy changes to the PRISMA 2009 statement

- Inclusion of the abstract reporting checklist within PRISMA 2020 (see item #2 and Table 2 ).

- Movement of the ‘Protocol and registration’ item from the start of the Methods section of the checklist to a new Other section, with addition of a sub-item recommending authors describe amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol (see item #24a-24c).

- Modification of the ‘Search’ item to recommend authors present full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites searched, not just at least one database (see item #7).

- Modification of the ‘Study selection’ item in the Methods section to emphasise the reporting of how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process (see item #8).

- Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Data items’ item recommending authors report how outcomes were defined, which results were sought, and methods for selecting a subset of results from included studies (see item #10a).

- Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Methods section into six sub-items recommending authors describe: the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis; any methods required to prepare the data for synthesis; any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses; any methods used to synthesise results; any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (such as subgroup analysis, meta-regression); and any sensitivity analyses used to assess robustness of the synthesised results (see item #13a-13f).

- Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Study selection’ item in the Results section recommending authors cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded (see item #16b).

- Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Results section into four sub-items recommending authors: briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among studies contributing to the synthesis; present results of all statistical syntheses conducted; present results of any investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results; and present results of any sensitivity analyses (see item #20a-20d).

- Addition of new items recommending authors report methods for and results of an assessment of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome (see items #15 and #22).

- Addition of a new item recommending authors declare any competing interests (see item #26).

- Addition of a new item recommending authors indicate whether data, analytic code and other materials used in the review are publicly available and if so, where they can be found (see item #27).

We recommend authors refer to PRISMA 2020 early in the writing process, because prospective consideration of the items may help to ensure that all the items are addressed. To help keep track of which items have been reported, the PRISMA statement website ( http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ) includes fillable templates of the checklists to download and complete (also available in S1 PRISMA 2020 checklist ). We have also created a web application that allows users to complete the checklist via a user-friendly interface [ 58 ] (available at https://prisma.shinyapps.io/checklist/ and adapted from the Transparency Checklist app [ 59 ]). The completed checklist can be exported to Word or PDF. Editable templates of the flow diagram can also be downloaded from the PRISMA statement website.

We have prepared an updated explanation and elaboration paper, in which we explain why reporting of each item is recommended and present bullet points that detail the reporting recommendations (which we refer to as elements).[ 41 ] The bullet-point structure is new to PRISMA 2020 and has been adopted to facilitate implementation of the guidance.[ 60 , 61 ] An expanded checklist, which comprises an abridged version of the elements presented in the explanation and elaboration paper, with references and some examples removed, is available in S2 PRISMA 2020 expanded checklist . Consulting the explanation and elaboration paper is recommended if further clarity or information is required.

Journals and publishers might impose word and section limits, and limits on the number of tables and figures allowed in the main report. In such cases, if the relevant information for some items already appears in a publicly accessible review protocol, referring to the protocol may suffice. Alternatively, placing detailed descriptions of the methods used or additional results (such as for less critical outcomes) in supplementary files is recommended. Ideally, supplementary files should be deposited to a general-purpose or institutional open-access repository that provides free and permanent access to the material (such as Open Science Framework, Dryad, figshare). A reference or link to the additional information should be included in the main report. Finally, although PRISMA 2020 provides a template for where information might be located, the suggested location should not be seen as prescriptive; the guiding principle is to ensure the information is reported.

Use of PRISMA 2020 has the potential to benefit many stakeholders. Complete reporting allows readers to assess the appropriateness of the methods, and therefore the trustworthiness of the findings. Presenting and summarising characteristics of studies contributing to a synthesis allows healthcare providers and policy makers to evaluate the applicability of the findings to their setting. Describing the certainty in the body of evidence for an outcome and the implications of findings should help policy makers, managers, and other decision makers formulate appropriate recommendations for practice or policy. Complete reporting of all PRISMA 2020 items also facilitates replication and review updates, as well as inclusion of systematic reviews in overviews (of systematic reviews) and guidelines, so teams can leverage work that is already done and decrease research waste.[ 36 , 62 , 63 ]

We updated the PRISMA 2009 statement by adapting the EQUATOR Network’s guidance for developing health research reporting guidelines.[ 64 ] We evaluated the reporting completeness of published systematic reviews,[ 17 , 21 , 36 , 37 ] reviewed the items included in other documents providing guidance for systematic reviews,[ 38 ] surveyed systematic review methodologists and journal editors for their views on how to revise the original PRISMA statement,[ 35 ] discussed the findings at an in-person meeting, and prepared this document through an iterative process. Our recommendations are informed by the reviews and survey conducted before the in-person meeting, theoretical considerations about which items facilitate replication and help users assess the risk of bias and applicability of systematic reviews, and co-authors’ experience with authoring and using systematic reviews.

Various strategies to increase the use of reporting guidelines and improve reporting have been proposed. They include educators introducing reporting guidelines into graduate curricula to promote good reporting habits of early career scientists [ 65 ]; journal editors and regulators endorsing use of reporting guidelines [ 18 ]; peer reviewers evaluating adherence to reporting guidelines [ 61 , 66 ]; journals requiring authors to indicate where in their manuscript they have adhered to each reporting item[ 67 ]; and authors using online writing tools that prompt complete reporting at the writing stage.[ 60 ] Multi-pronged interventions, where more than one of these strategies are combined, may be more effective (such as completion of checklists coupled with editorial checks).[ 68 ] However, of 31 interventions proposed to increase adherence to reporting guidelines, the effects of only 11 have been evaluated, mostly in observational studies at high risk of bias due to confounding.[ 69 ] It is therefore unclear which strategies should be used. Future research might explore barriers and facilitators to the use of PRISMA 2020 by authors, editors, and peer reviewers, designing interventions that address the identified barriers, and evaluating those interventions using randomised trials. To inform possible revisions to the guideline, it would also be valuable to conduct think-aloud studies [ 70 ] to understand how systematic reviewers interpret the items, and reliability studies to identify items where there is varied interpretation of the items.

We encourage readers to submit evidence that informs any of the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 (via the PRISMA statement website: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ). To enhance accessibility of PRISMA 2020, several translations of the guideline are under way (see available translations at the PRISMA statement website). We encourage journal editors and publishers to raise awareness of PRISMA 2020 (for example, by referring to it in journal “Instructions to authors”), endorsing its use, advising editors and peer reviewers to evaluate submitted systematic reviews against the PRISMA 2020 checklists, and making changes to journal policies to accommodate the new reporting recommendations. We recommend existing PRISMA extensions [ 47 , 49 – 53 , 71 , 72 ] be updated to reflect PRISMA 2020 and advise developers of new PRISMA extensions to use PRISMA 2020 as the foundation document.

We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders. Ultimately, we hope that uptake of the guideline will lead to more transparent, complete, and accurate reporting of systematic reviews, thus facilitating evidence based decision making.

Supporting information

S1 prisma 2020 checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583.s001

S2 PRISMA 2020 expanded checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583.s002

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to the late Douglas G Altman and Alessandro Liberati, whose contributions were fundamental to the development and implementation of the original PRISMA statement.

We thank the following contributors who completed the survey to inform discussions at the development meeting: Xavier Armoiry, Edoardo Aromataris, Ana Patricia Ayala, Ethan M Balk, Virginia Barbour, Elaine Beller, Jesse A Berlin, Lisa Bero, Zhao-Xiang Bian, Jean Joel Bigna, Ferrán Catalá-López, Anna Chaimani, Mike Clarke, Tammy Clifford, Ioana A Cristea, Miranda Cumpston, Sofia Dias, Corinna Dressler, Ivan D Florez, Joel J Gagnier, Chantelle Garritty, Long Ge, Davina Ghersi, Sean Grant, Gordon Guyatt, Neal R Haddaway, Julian PT Higgins, Sally Hopewell, Brian Hutton, Jamie J Kirkham, Jos Kleijnen, Julia Koricheva, Joey SW Kwong, Toby J Lasserson, Julia H Littell, Yoon K Loke, Malcolm R Macleod, Chris G Maher, Ana Marušic, Dimitris Mavridis, Jessie McGowan, Matthew DF McInnes, Philippa Middleton, Karel G Moons, Zachary Munn, Jane Noyes, Barbara Nußbaumer-Streit, Donald L Patrick, Tatiana Pereira-Cenci, Ba’ Pham, Bob Phillips, Dawid Pieper, Michelle Pollock, Daniel S Quintana, Drummond Rennie, Melissa L Rethlefsen, Hannah R Rothstein, Maroeska M Rovers, Rebecca Ryan, Georgia Salanti, Ian J Saldanha, Margaret Sampson, Nancy Santesso, Rafael Sarkis-Onofre, Jelena Savović, Christopher H Schmid, Kenneth F Schulz, Guido Schwarzer, Beverley J Shea, Paul G Shekelle, Farhad Shokraneh, Mark Simmonds, Nicole Skoetz, Sharon E Straus, Anneliese Synnot, Emily E Tanner-Smith, Brett D Thombs, Hilary Thomson, Alexander Tsertsvadze, Peter Tugwell, Tari Turner, Lesley Uttley, Jeffrey C Valentine, Matt Vassar, Areti Angeliki Veroniki, Meera Viswanathan, Cole Wayant, Paul Whaley, and Kehu Yang. We thank the following contributors who provided feedback on a preliminary version of the PRISMA 2020 checklist: Jo Abbott, Fionn Büttner, Patricia Correia-Santos, Victoria Freeman, Emily A Hennessy, Rakibul Islam, Amalia (Emily) Karahalios, Kasper Krommes, Andreas Lundh, Dafne Port Nascimento, Davina Robson, Catherine Schenck-Yglesias, Mary M Scott, Sarah Tanveer and Pavel Zhelnov. We thank Abigail H Goben, Melissa L Rethlefsen, Tanja Rombey, Anna Scott, and Farhad Shokraneh for their helpful comments on the preprints of the PRISMA 2020 papers. We thank Edoardo Aromataris, Stephanie Chang, Toby Lasserson and David Schriger for their helpful peer review comments on the PRISMA 2020 papers.