share this!

August 16, 2021

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in

by Sara M Moniuszko

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

'get organized' ahead of back-to-school.

©2021 USA Today Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Global study shows a third more insects come out after dark

10 hours ago

Cicada-palooza! Billions of bugs to blanket America

12 hours ago

Getting dynamic information from static snapshots

Ancient Maya blessed their ballcourts: Researchers find evidence of ceremonial offerings in Mexico

Optical barcodes expand range of high-resolution sensor

Apr 26, 2024

Ridesourcing platforms thrive on socio-economic inequality, say researchers

Did Vesuvius bury the home of the first Roman emperor?

Florida dolphin found with highly pathogenic avian flu: Report

A new way to study and help prevent landslides

New algorithm cuts through 'noisy' data to better predict tipping points

Relevant physicsforums posts, why are physicists so informal with mathematics.

53 minutes ago

Studying "Useful" vs. "Useless" Stuff in School

4 hours ago

Digital oscilloscope for high school use

Apr 25, 2024

Motivating high school Physics students with Popcorn Physics

Apr 3, 2024

How is Physics taught without Calculus?

Mar 29, 2024

The changing physics curriculum in 1961

Mar 24, 2024

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Smartphones are lowering student's grades, study finds

Aug 18, 2020

Doing homework is associated with change in students' personality

Oct 6, 2017

Scholar suggests ways to craft more effective homework assignments

Oct 1, 2015

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Aug 29, 2019

How much math, science homework is too much?

Mar 23, 2015

Anxiety, depression, burnout rising as college students prepare to return to campus

Jul 26, 2021

Recommended for you

Training of brain processes makes reading more efficient

Apr 18, 2024

Researchers find lower grades given to students with surnames that come later in alphabetical order

Apr 17, 2024

Earth, the sun and a bike wheel: Why your high-school textbook was wrong about the shape of Earth's orbit

Apr 8, 2024

Touchibo, a robot that fosters inclusion in education through touch

Apr 5, 2024

More than money, family and community bonds prep teens for college success: Study

Research reveals significant effects of onscreen instructors during video classes in aiding student learning

Mar 25, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Second Opinion

- Research & Innovation

- Patients & Families

- Health Professionals

- Recently Visited

- Segunda opinión

- Refer a patient

- MyChart Login

Healthier, Happy Lives Blog

Sort articles by..., sort by category.

- Celebrating Volunteers

- Community Outreach

- Construction Updates

- Family-Centered Care

- Healthy Eating

- Heart Center

- Interesting Things

- Mental Health

- Patient Stories

- Research and Innovation

- Safety Tips

- Sustainability

- World-Class Care

About Our Blog

- Back-to-School

- Pediatric Technology

Latest Posts

- Tween Misses Old Heart but Grateful for New One After Transplant

- Q&A: Answering the ‘Why’ Behind Liver Transplant Inequity

- Stanford Medicine Children’s Health Draws Attention to Sustainability Through Recycled Art

- Boy With Short Bowel Syndrome Living the Dream of a Better Life

- NICU Sims Set Stage for Lifesaving Care

Health Hazards of Homework

March 18, 2014 | Julie Greicius Pediatrics .

A new study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education and colleagues found that students in high-performing schools who did excessive hours of homework “experienced greater behavioral engagement in school but also more academic stress, physical health problems, and lack of balance in their lives.”

Those health problems ranged from stress, headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems, to psycho-social effects like dropping activities, not seeing friends or family, and not pursuing hobbies they enjoy.

In the Stanford Report story about the research, Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of the study published in the Journal of Experimental Education , says, “Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good.”

The study was based on survey data from a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in California communities in which median household income exceeded $90,000. Of the students surveyed, homework volume averaged about 3.1 hours each night.

“It is time to re-evaluate how the school environment is preparing our high school student for today’s workplace,” says Neville Golden, MD , chief of adolescent medicine at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health and a professor at the School of Medicine. “This landmark study shows that excessive homework is counterproductive, leading to sleep deprivation, school stress and other health problems. Parents can best support their children in these demanding academic environments by advocating for them through direct communication with teachers and school administrators about homework load.”

Related Posts

Top-ranked group group in Los Gatos, Calif., is now a part of one of the…

The Stanford Medicine Children’s Health network continues to grow with our newest addition, Town and…

- Julie Greicius

- more by this author...

Connect with us:

Download our App:

ABOUT STANFORD MEDICINE CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

LUCILE PACKARD FOUNDATION FOR CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Get Involved

- Volunteering Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

- Our Hospital

- Send a Greeting Card

- New Hospital

- Refer a Patient

- Pay Your Bill

Also Find Us on:

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Code of Conduct

- Price Transparency

- Stanford School of Medicine

- Stanford Health Care

- Stanford University

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Stanford research shows pitfalls of homework

A Stanford researcher found that students in high-achieving communities who spend too much time on homework experience more stress, physical health problems, a lack of balance and even alienation from society. More than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive, according to the study.

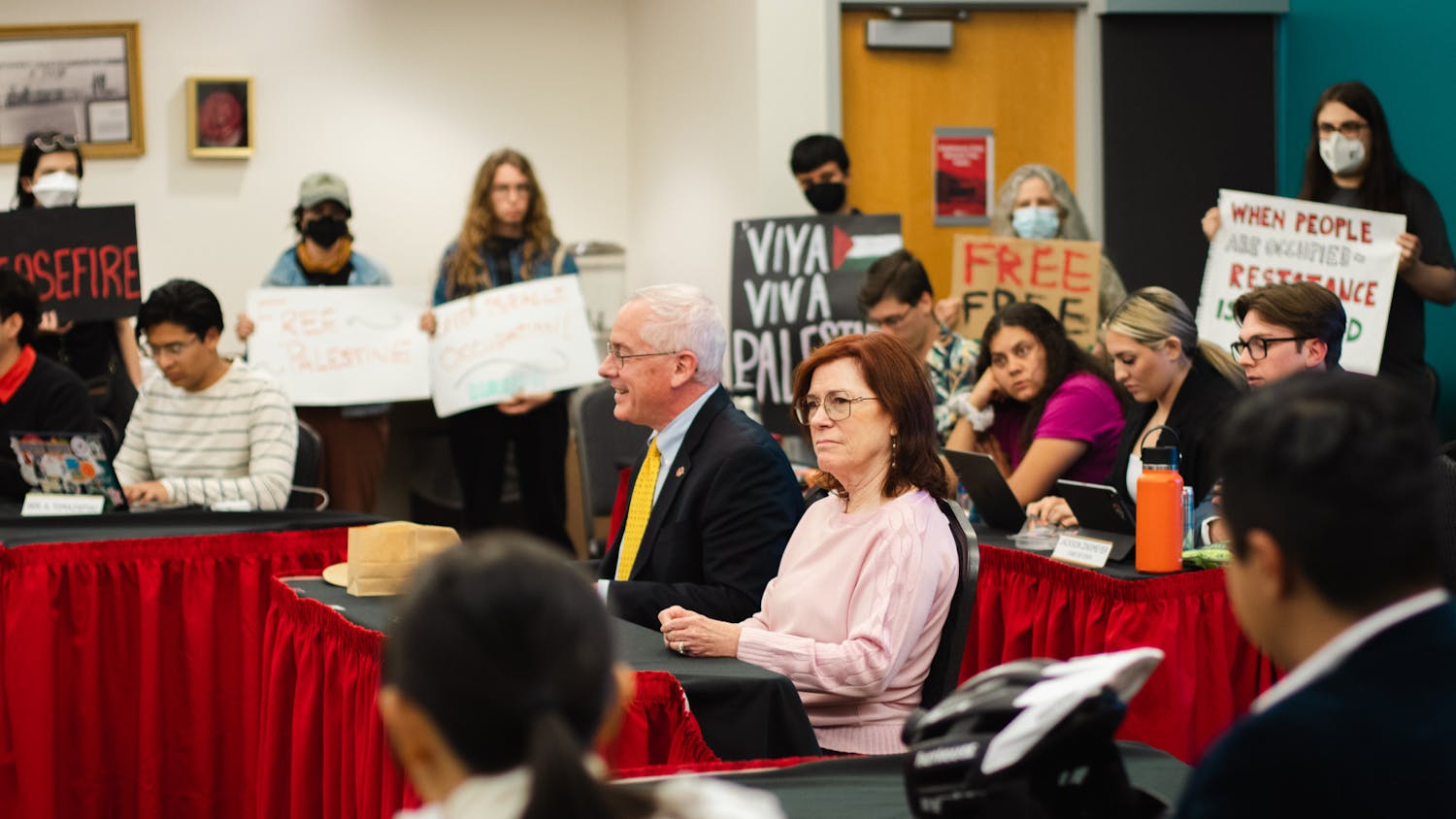

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

• Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

• Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

• Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Opinion | Social-Emotional Learning

If we’re serious about student well-being, we must change the systems students learn in, here are five steps high schools can take to support students' mental health., by tim klein and belle liang oct 14, 2022.

Shutterstock / SvetaZi

Educators and parents started this school year with bated breath. Last year’s stress led to record levels of teacher burnout and mental health challenges for students.

Even before the pandemic, a mental health crisis among high schoolers loomed. According to a survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2019, 37 percent of high school students said they experienced persistent sadness or hopelessness and 19 percent reported suicidality. In response, more than half of all U.S. states mandated that schools have a mental health curriculum or include mental health in their standards .

As mental health professionals and co-authors of a book about the pressure and stress facing high school students, we’ve spent our entire careers supporting students’ mental health. Traditionally, mental health interventions are individualized and they focus on helping students manage and change their behaviors to cope with challenges they’re facing. But while working with schools and colleges across the globe as we conducted research for our book , we realized that most interventions don’t address systemic issues causing mental health problems in the first place.

It’s time we acknowledge that our education systems are directly contributing to the youth mental health crisis. And if we are serious about student well-being, we must change the systems they learn in.

Here are five bold steps that high schools can take to boost mental health.

Limit Homework or Make it Optional

Imagine applying for a job, and the hiring manager informs you that in addition to a full workday in the office, you’ll be assigned three more hours of work every night. Does this sound like a healthy work-life balance? Most adults would consider this expectation ridiculous and unsustainable. Yet, this is the workload most schools place on high school students.

Research shows that excessive homework leads to increased stress, physical health problems and a lack of balance in students' lives. And studies have shown that more than two hours of daily homework can be counterproductive , yet many teachers assign more.

Homework proponents argue that homework improves academic performance. Indeed, a meta-analysis of research on this issue found a correlation between homework and achievement. But correlation isn’t causation. Does homework cause achievement or do high achievers do more homework? While it’s likely that homework completion signals student engagement, which in turn leads to academic achievement, there’s little evidence to suggest that homework itself improves engagement in learning.

Another common argument is that homework helps students develop skills related to problem-solving, time-management and self-direction. But these skills can be explicitly taught during the school day rather than after school.

Limiting homework or moving to an optional homework policy not only supports student well-being, but it can also create a more equitable learning environment. According to the American Psychological Association, students from more affluent families are more likely to have access to resources such as devices, internet, dedicated work space and the support necessary to complete their work successfully—and homework can highlight those inequities .

Whether a school limits homework or makes it optional, it’s critical to remember that more important than the amount of homework assigned, is designing the type of activities that engage students in learning. When students are intrinsically motivated to do their homework, they are more engaged in the work, which in turn is associated with academic achievement.

Cap the Number of APs Students Can Take

Advanced Placement courses give students a taste of college-level work and, in theory, allow them to earn college credits early. Getting good grades on AP exams is associated with higher GPAs in high school and success in college, but the research tends to be correlational rather than causational.

In 2008, a little over 180,000 students took three or more AP exams. By 2018, that number had ballooned to almost 350,000 students .

However, this expansion has come at the expense of student well-being.

Over the years, we’ve heard many students express that they feel pressure to take as many AP classes as possible, which overloads them with work. That’s troubling because studies show that students who take AP classes and exams are twice as likely to report adverse physical and emotional health .

AP courses and exams also raise complex issues of equity. In 2019, two out of three Harvard freshmen reported taking AP Calculus in high school, according to Jeff Selingo, author of “ Who Gets In and Why: A Year Inside College Admissions ,” yet only half of all high schools in the country offer the course. And opportunity gaps exist for advanced coursework such as AP courses and dual enrollment, with inequitable distribution of funding and support impacting which students are enrolling and experiencing success. According to the Center for American Progress, “National data from the Civil Rights Data Collection show that students who are Black, Indigenous, and other non-Black people of color (BIPOC) are not enrolled in AP courses at rates comparable to their white and Asian peers and experience less success when they are—and the analysis for this report finds this to be true even when they attend schools with similar levels of AP course availability.”

Limiting the number of AP courses students take can protect mental health and create a more equitable experience for students.

Eliminate Class Rankings

In a study we conducted about mental health problems among high school girls, we found that a primary driver of stress was their perception of school as a hypercompetitive, zero-sum game where pervasive peer pressure to perform reigns supreme.

Class rankings fuel these cutthroat environments. They send a toxic message to young people: success requires doing better than your peers.

Ranking systems help highly selective colleges decide which students to admit or reject for admission. The purpose of high school is to develop students to their own full potential, rather than causing them to fixate on measuring up to others. Research shows that ranking systems undercut students’ learning and damage social relationships by turning peers into opponents.

Eliminating class rankings sends a powerful message to students that they are more than a number.

Become an Admission Test Objector

COVID-19 ushered in the era of test-optional admissions. De-centering standardized tests in the college application process is unequivocally a good thing. Standardized tests don’t predict student success in college , they only widen the achievement gap between privileged and underprivileged students and damage students' mental health .

Going “test optional” is an excellent first step, but it's not enough.

Even as more colleges have made tests optional, affluent students submit test scores at a higher rate than their lower-income peers and are admitted at higher rates , suggesting that testing still gives them an edge.

High schools must adhere to standardized test mandates, but they don’t have to endorse them. They can become test objectors by publicly proclaiming that these tests hold no inherent value. They can stop teaching to the test and educate parents on why they are doing so. Counseling departments can inform colleges that their school is a test objector so admission teams won’t penalize students.

Of course, students and families will still find ways to wield these tests as a competitive advantage. Over time, the more schools and educators unite to denounce these tests, the less power they will hold over students and families.

Big change starts with small steps.

Stand For What You Value

Critics may argue that such policies might hurt student outcomes. How will colleges evaluate school rigor if we limit AP courses and homework? How will students demonstrate their merits without class rankings and standardized test scores?

The truth is, the best school systems in the world succeed without homework, standardized test scores or an obsession with rigorous courses. And many U.S. schools have found creative and empowering ways to showcase student merit beyond rankings and test scores.

If we aren’t willing to change policies and practices that have been shown to harm students’ well-being, we have to ask ourselves: Do we really value mental health?

Thankfully, it doesn’t have to be an either/or scenario: We can design school systems that help students thrive academically and psychologically.

Belle Liang and Tim Klein are mental health professionals and co-authors of “How To Navigate Life: The New Science of Finding Your Way in School, Career and Life.”

More from EdSurge

Diversity and Equity

Researchers have identified the starkest cases of school district segregation, by nadia tamez-robledo.

EdSurge Podcast

Whatever happened to building a metaverse for education, by jeffrey r. young.

Is It Time for a National Conversation About Eliminating Letter Grades?

Artificial Intelligence

Ai guidelines for k-12 aim to bring order to the ‘wild west’.

Journalism that ignites your curiosity about education.

EdSurge is an editorially independent project of and

- Product Index

- Write for us

- Advertising

FOLLOW EDSURGE

© 2024 All Rights Reserved

Get Started Today!

- Centre Details

- Ask A Question

- Change Location

- Programs & More

Infographic: How Does Homework Actually Affect Students?

Homework is an important part of engaging students outside of the classroom. How does homework affect students?

It carries educational benefits for all age groups, including time management and organization. Homework also provides students with the ability to think beyond what is taught in class.

The not-so-good news is these benefits only occur when students are engaged and ready to learn. But, the more homework they get, the less they want to engage.

The Negative Effects on Students

Homework can affect students’ health, social life and grades. The hours logged in class, and the hours logged on schoolwork can lead to students feeling overwhelmed and unmotivated. Navigating the line between developing learning skills and feeling frustrated can be tricky.

Homework is an important part of being successful inside and outside of the classroom, but too much of it can actually have the opposite effect. Students who spend too much time on homework are not always able to meet other needs, like being physically and socially active. Ultimately, the amount of homework a student has can impact a lot more than his or her grades.

Find out how too much homework actually affects students.

How Does Homework Affect Students’ Health?

Homework can affect both students’ physical and mental health. According to a study by Stanford University, 56 per cent of students considered homework a primary source of stress. Too much homework can result in lack of sleep, headaches, exhaustion and weight loss. Excessive homework can also result in poor eating habits, with families choosing fast food as a faster alternative.

How Does Homework Affect Students’ Social Life?

Extracurricular activities and social time gives students a chance to refresh their minds and bodies. But students who have large amounts of homework have less time to spend with their families and friends. This can leave them feeling isolated and without a support system. For older students, balancing homework and part-time work makes it harder to balance school and other tasks. Without time to socialize and relax, students can become increasingly stressed, impacting life at school and at home.

How Does Homework Affect Students’ Grades?

After a full day of learning in class, students can become burnt out if they have too much homework. When this happens, the child may stop completing homework or rely on a parent to assist with homework. As a result, the benefits of homework are lost and grades can start to slip.

Too much homework can also result in less active learning, a type of learning that occurs in context and encourages participation. Active learning promotes the analysis and application of class content in real world settings. Homework does not always provide these opportunities, leading to boredom and a lack of problem-solving skills.

Take a look at how homework affects students and how to help with homework.

How Can Parents Help?

Being an active part of children’s homework routine is a major part of understanding feelings and of be able to provide the needed support. As parents, you can help your child have a stress-free homework experience. Sticking to a clear and organized homework routine helps children develop better homework habits as they get older. This routine also comes in handy when homework becomes more difficult and time-consuming.

Learn more about the current world of homework, and how you can help your child stay engaged.

Embed this on your site

<a href=”https://www.oxfordlearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/how-homework-affects-students-infographic.jpg” target=”_blank”><img style=”width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; height: auto;” alt=”How Does Homework Affect Students” src=”https://www.oxfordlearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/how-homework-affects-students-infographic.jpg” /></a><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /><br /> <a href=”www.oxfordlearning.com”>Oxford Learning Centres</a>

Check Out These Additional Homework Resources

Does Your Child Struggle With Homework?

- Best Methods of Self Study for Students

- Developing a Growth Mindset — 5 Tips for Parents

Study Break Tips: How To Take A Study Break That Works

Related homework resources.

Homework, Organization, Studying

Homework procrastination: why do students procrastinate.

Understanding Dysgraphia and How Tutoring Can Help

Unwrapping the 12 Days of Holiday Skills

Canadian Attitudes Toward Homework

Find an oxford learning ® location near you, we have over 100 centres across canada.

When Is Homework Stressful? Its Effects on Students’ Mental Health

Are you wondering when is homework stressful? Well, homework is a vital constituent in keeping students attentive to the course covered in a class. By applying the lessons, students learned in class, they can gain a mastery of the material by reflecting on it in greater detail and applying what they learned through homework.

However, students get advantages from homework, as it improves soft skills like organisation and time management which are important after high school. However, the additional work usually causes anxiety for both the parents and the child. As their load of homework accumulates, some students may find themselves growing more and more bored.

Students may take assistance online and ask someone to do my online homework . As there are many platforms available for the students such as Chegg, Scholarly Help, and Quizlet offering academic services that can assist students in completing their homework on time.

Negative impact of homework

There are the following reasons why is homework stressful and leads to depression for students and affect their mental health. As they work hard on their assignments for alarmingly long periods, students’ mental health is repeatedly put at risk. Here are some serious arguments against too much homework.

No uniqueness

Homework should be intended to encourage children to express themselves more creatively. Teachers must assign kids intriguing assignments that highlight their uniqueness. similar to writing an essay on a topic they enjoy.

Moreover, the key is encouraging the child instead of criticizing him for writing a poor essay so that he can express himself more creatively.

Lack of sleep

One of the most prevalent adverse effects of schoolwork is lack of sleep. The average student only gets about 5 hours of sleep per night since they stay up late to complete their homework, even though the body needs at least 7 hours of sleep every day. Lack of sleep has an impact on both mental and physical health.

No pleasure

Students learn more effectively while they are having fun. They typically learn things more quickly when their minds are not clouded by fear. However, the fear factor that most teachers introduce into homework causes kids to turn to unethical means of completing their assignments.

Excessive homework

The lack of coordination between teachers in the existing educational system is a concern. As a result, teachers frequently end up assigning children far more work than they can handle. In such circumstances, children turn to cheat on their schoolwork by either copying their friends’ work or using online resources that assist with homework.

Anxiety level

Homework stress can increase anxiety levels and that could hurt the blood pressure norms in young people . Do you know? Around 3.5% of young people in the USA have high blood pressure. So why is homework stressful for children when homework is meant to be enjoyable and something they look forward to doing? It is simple to reject this claim by asserting that schoolwork is never enjoyable, yet with some careful consideration and preparation, homework may become pleasurable.

No time for personal matters

Students that have an excessive amount of homework miss out on personal time. They can’t get enough enjoyment. There is little time left over for hobbies, interpersonal interaction with colleagues, and other activities.

However, many students dislike doing their assignments since they don’t have enough time. As they grow to detest it, they can stop learning. In any case, it has a significant negative impact on their mental health.

Children are no different than everyone else in need of a break. Weekends with no homework should be considered by schools so that kids have time to unwind and prepare for the coming week. Without a break, doing homework all week long might be stressful.

How do parents help kids with homework?

Encouraging children’s well-being and health begins with parents being involved in their children’s lives. By taking part in their homework routine, you can see any issues your child may be having and offer them the necessary support.

Set up a routine

Your student will develop and maintain good study habits if you have a clear and organized homework regimen. If there is still a lot of schoolwork to finish, try putting a time limit. Students must obtain regular, good sleep every single night.

Observe carefully

The student is ultimately responsible for their homework. Because of this, parents should only focus on ensuring that their children are on track with their assignments and leave it to the teacher to determine what skills the students have and have not learned in class.

Listen to your child

One of the nicest things a parent can do for their kids is to ask open-ended questions and listen to their responses. Many kids are reluctant to acknowledge they are struggling with their homework because they fear being labelled as failures or lazy if they do.

However, every parent wants their child to succeed to the best of their ability, but it’s crucial to be prepared to ease the pressure if your child starts to show signs of being overburdened with homework.

Talk to your teachers

Also, make sure to contact the teacher with any problems regarding your homework by phone or email. Additionally, it demonstrates to your student that you and their teacher are working together to further their education.

Homework with friends

If you are still thinking is homework stressful then It’s better to do homework with buddies because it gives them these advantages. Their stress is reduced by collaborating, interacting, and sharing with peers.

Additionally, students are more relaxed when they work on homework with pals. It makes even having too much homework manageable by ensuring they receive the support they require when working on the assignment. Additionally, it improves their communication abilities.

However, doing homework with friends guarantees that one learns how to communicate well and express themselves.

Review homework plan

Create a schedule for finishing schoolwork on time with your child. Every few weeks, review the strategy and make any necessary adjustments. Gratefully, more schools are making an effort to control the quantity of homework assigned to children to lessen the stress this produces.

Bottom line

Finally, be aware that homework-related stress is fairly prevalent and is likely to occasionally affect you or your student. Sometimes all you or your kid needs to calm down and get back on track is a brief moment of comfort. So if you are a student and wondering if is homework stressful then you must go through this blog.

While homework is a crucial component of a student’s education, when kids are overwhelmed by the amount of work they have to perform, the advantages of homework can be lost and grades can suffer. Finding a balance that ensures students understand the material covered in class without becoming overburdened is therefore essential.

Zuella Montemayor did her degree in psychology at the University of Toronto. She is interested in mental health, wellness, and lifestyle.

Psychreg is a digital media company and not a clinical company. Our content does not constitute a medical or psychological consultation. See a certified medical or mental health professional for diagnosis.

- Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2014–2034 Psychreg Ltd

- PSYCHREG JOURNAL

- MEET OUR WRITERS

- MEET THE TEAM

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health

School educational models and child mental health among K-12 students: a scoping review

1 The International Peace Maternity & Child Health Hospital, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Embryo Original Diseases, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, No. 910 Hengshan Road, Shanghai, 200030 China

Yining Jiang

Xiangrong guo.

2 MOE-Shanghai Key Laboratory of Children’s Environmental Health, Department of Child and Adolescent Healthcare, Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, 200092 China

Associated Data

The data analysed in this review are available from the corresponding author upon request.

The promotion of mental health among children and adolescents is a public health imperative worldwide, and schools have been proposed as the primary and targeted settings for mental health promotion for students in grades K-12. This review sought to provide a comprehensive understanding of key factors involved in models of school education contributing to student mental health development, interrelationships among these factors and the cross-cultural differences across nations and societies.

This scoping review followed the framework of Arksey and O’Malley and holistically reviewed the current evidence on the potential impacts of school-related factors or school-based interventions on student mental health in recent 5 years based on the PubMed, Web of Science, Embase and PsycExtra databases.

Results/findings

After screening 558 full-texts, this review contained a total of 197 original articles on school education and student mental health. Based on the five key factors (including curriculum, homework and tests, physical activities, interpersonal relationships and after-school activities) identified in student mental development according to thematic analyses, a multi-component school educational model integrating academic, social and physical factors was proposed so as to conceptualize the five school-based dimensions for K-12 students to promote student mental health development.

Conclusions

The lessons learned from previous studies indicate that developing multi-component school strategies to promote student mental health remains a major challenge. This review may help establish appropriate school educational models and call for a greater emphasis on advancement of student mental health in the K-12 school context among different nations or societies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13034-022-00469-8.

Introduction

In recent years, mental health conditions among children and adolescents have received considerable attention as a public health concern. Globally about 10–20% of children and adolescents experience mental health problems [ 1 , 2 ], and mental health problems in early life may have the potential for long-term adverse consequences [ 3 , 4 ]. In 2019, the World Health Organization has pointed out that childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the acquisition of socio-emotional capabilities and for prevention of mental health problems [ 5 ]. A comprehensive multi-level solution to child mental health problems needs to be put forward for the sake of a healthier lifestyle and environment for future generations.

The school is a unique resource to help children improve their mental health. A few generations ago, schools’ priority was to teach the traditional subjects, such as reading, writing, and arithmetic. However, children are now spending a large amount of time at school where they learn, play and socialize. For some students, schools have a positive influence on their mental health. While for others, schools can present as a considerable source of stress, worry, and unhappiness, and hinder academic achievement [ 2 ]. According to Greenberg et al., today’s schools need to teach beyond basic skills (such as reading, writing, and counting skills) and enhance students’ social-emotional competence, characters, health, and civic engagement [ 6 ]. Therefore, universal mental health promotion in school settings is recognized to be particularly effective in improving students’ emotional well-being [ 2 , 7 ].

Research evidence over the last two decades has shown that schools can make a difference to students’ mental health [ 8 ]. Previous related systematic reviews or meta-analyses focused on the effects of a particular school-based intervention on child mental health [ 9 , 10 ] and answered a specific question with available research, however, reviews covering different school-related factors or school-based interventions are still lacking. An appropriate model of school education requires the combination of different school-related factors (such as curriculum, homework, and physical activities) and therefore needs to focus on multiple primary outcomes. Thus, we consider that a scoping review may be more appropriate to help us synthesize the recent evidence than a systematic review or meta-analysis, as the wide coverage and the heterogeneous nature of related literature focusing on multiple primary outcomes are not amenable to a more precise systematic review or meta-analysis [ 11 ]. To the best of our knowledge, this review is among the first to provide a comprehensive overview of available evidence on the potential impacts of multiple school-related factors or school-based interventions on student mental health, and identify school-related risk/protective factors involved in the development of mental health problems among K-12 students, and therefore, to help develop a holistic model of K-12 education.

A scoping review was systematically conducted following the methodological framework of Arksey and O'Malley [ 12 ]: defining the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; data extraction; and summarizing and reporting results. The protocol for this review was specified in advance and submitted for registration in the PROSPERO database (Reference number, CRD42019123126).

Defining the research question (stage 1)

For this review, we sought to answer the following questions:

- What is known from the existing literature on the potential impacts of school-related factors or school-based interventions on student mental health?

- What are the interrelationships among these factors involved in the school educational process?

- What are the cross-cultural differences in K-12 education process across nations and societies?

Identifying relevant studies (stage 2)

The search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science and Embase electronic databases, and the dates of the published articles included in the search were limited to the last 5 years until 23 March 2021. The PsycExtra database was also searched to identify relevant evidence in the grey literature [ 13 ]. In recent 5 years, mental disorders among children and adolescents have increased at an alarming rate [ 14 , 15 ] and relevant policies calling for a greater role of schools in promoting student mental health have been issued in different countries [ 16 – 18 ], making educational settings at the forefront of the prevention initiative globally. Therefore, limiting research source published in the past 5 years was pre-defined since these publications reflected the newest discoveries, theories, processes, or practices. Search terms were selected based on the eligibility criteria and outcomes of interest were described as follows (Additional file 1 : Table S1). The search strategy was peer-reviewed by the librarian of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Study selection (stage 3)

T.Y. and Y.J. independently identified relevant articles by screening the titles, reviewing the abstracts and full-text articles. If any disagreement arises, the disagreement shall be resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and a third reviewer (J. X.).

Inclusion criteria were (1) according to the study designs: only randomized controlled trials (RCT)/quasi-RCT, longitudinal and cross-sectional studies; (2) according to the languages: articles only published in English or Chinese; (3) according to the ages of the subjects: preschoolers (3.5–5 years of age), children (6–11 years of age) and adolescents (12–18 years of age); and (4) according to the study topics: only articles examining the associations between factors involved in the school education and student mental health outcomes (psychological distress, such as depression, anxiety, stress, self-injury, suicide; and/or psychological well-being, such as self-esteem, self-concept, self-efficacy, optimism and happiness) in educational settings. Exclusion criteria: (1) Conference abstracts, case report/series, and descriptive articles were excluded due to overall quality and reliability. (2) Studies investigating problems potentially on a causal pathway to mental health disorders but without close associations with school education models (such as problems probably caused by family backgrounds) were excluded. (3) Studies using schools as the recruitment places but without school-related topics were also excluded.

Data extraction (stage 4)

T.Y. and Y.J., and X.G., Y. Z., H.H. extracted data from the included studies using a pre-defined extraction sheet. Researchers extracted the following information from each eligible study: study background (name of the first author, publication year, and study location), sample characteristics (number of participants, ages of participants, and sex proportion), design [intervention (RCT or quasi-RCT), or observational (cross-sectional or longitudinal) study], and instruments used to assess exposures in school settings and mental health outcomes. For intervention studies (RCTs and quasi-RCTs), we also extracted weeks of intervention, descriptions of the program, duration and frequency. T.Y. reviewed all the data extraction sheets under the supervision of J. X.

Summarizing and reporting the results (stage 5)

Results were summarized and reported using a narrative synthesis approach. Studies were sorted according to (a) factors/exposures associated with child and adolescent mental health in educational settings, and (b) components of school-based interventions to facilitate student mental health development. Key findings from the studies were then compared, contrasted and synthesized to illuminate themes which appeared across multiple investigations.

Search results and characteristics of the included articles

The search yielded 25,338 citations, from which 558 were screened in full-text. Finally, a total of 197 original articles were included in this scoping review: 72 RCTs (including individually randomized and cluster-randomized trials), 27 quasi-RCTs, 29 longitudinal studies and 69 cross-sectional studies (Fig. 1 for details). Based on thematic analyses, the included studies were analyzed and thematically grouped into five overarching categories based on the common themes in the types of intervention programs or exposures in the school context: curriculum, homework and tests, interpersonal relationships, physical activity and after-school activities. Table Table1 1 provided a numerical summary of the characteristics of the included articles. The 197 articles included data from 46 countries in total, covering 24 European countries, 13 Asian countries, 4 American countries, 3 African countries, and 2 Oceanian countries. Most intervention studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 16), followed by Australia (n = 11) and the United Kingdom (n = 11). Most observational studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 19), followed by China (n = 15) and Canada (n = 8). Figure 2 illustrated the geographical distribution of the included studies. Further detailed descriptions of the intervention studies or observational studies were provided in Additional file 1 : Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

Study selection process

Summary of the included articles

Geographical distribution of included studies: A intervention studies; B observational studies

The association between school curriculum and student mental health was investigated in four cross-sectional studies. Mathematics performance was found to be adversely associated with levels of anxiety or negative emotional responses among primary school students [ 19 ]. However, in middle schools, difficulties and stressors students may encounter in learning academic lessons (such as difficulties/stressors in taking notes and understanding teachers’ instructions) could contribute to lowered self-esteem [ 20 ] and increased suicidal ideation or attempts [ 21 ]. Innovative integration of different courses instead of the traditional approach of teaching biology, chemistry, and physics separately, could improve students’ self-concept [ 22 ].

To promote student mental health, 64 intervention studies were involved in innovative curricula integrating different types of competencies, including social emotional learning (SEL), mindfulness-intervention, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-based curriculum, life skills training, stress management curriculum, and so on (Fig. 3 ). Curricula focusing on SEL put an emphasis on the development of child social-emotional skills such as managing emotions, coping skills and empathy [ 23 ], and showed positive effects on depression, anxiety, stress, negative affect and emotional problems [ 23 – 37 ], especially in children with psychological symptoms [ 24 ] and girls [ 23 , 27 ], as well as increased prosocial behaviors [ 38 ], self-esteem [ 39 – 42 ] and positive affect [ 43 ]. However, four programs reported non-significant effects of SEL on student mental health outcomes [ 44 – 47 ], while two programs demonstrated increased levels of anxiety [ 48 ] and a reduction of subjective well-being [ 49 ] at post-intervention. Mindfulness-based curriculum showed its potential to endorse positive outcomes for youth including reduced emotional problems and negative affect [ 50 – 56 ] as well as increased well-being and positive emotions [ 51 , 52 , 57 – 60 ], especially among high-risk children with emotional problems or perceived stress before interventions [ 50 , 53 ]. However, non-significant effects were also reported in an Australian study in secondary schools [ 61 ]. Curricula based on CBT targeted children at risk or with early symptoms of mental illness [ 62 – 67 ], or all students regardless of symptom levels as a universal program [ 68 – 70 ], and could impose a positive effect on self-esteem, well-being, distress, stress and suicidality. However, a universal CBT trial in Swedish primary schools found no evidence of long-term effects of such program on anxiety prevention [ 71 ]. Five intervention studies based on life-skill-training were found to be effective in promoting self-efficacy [ 72 , 73 ], self-esteem [ 73 , 74 ], and reducing depression/anxiety-like symptoms [ 72 , 75 , 76 ]. Courses covering stress management skills have also been reported to improve life satisfaction, increase happiness and decrease anxiety levels among students in developing countries [ 77 – 79 ]. In practice, innovative teaching forms such as the game play [ 67 , 80 , 81 ] and outdoor learning [ 82 , 83 ] embedded in the traditional classes could help address the mental health and social participation concerns for children and youth. Limited evidence supported the mental health benefits of resilience-based curricula [ 84 – 86 ], which deserve further studies.

Harvest plots for overview of curriculum-based intervention studies, grouped by different types of curriculum-based interventions. The height of the bars corresponded to the sample sizes on a logarithmic scale of each study. Red bars represented positive effects of interventions on student mental health outcomes, grey bars represented non-significant effects on student mental health outcomes, and black bars represented negative effects on student mental health outcomes

Large cluster-randomized trials utilizing multi-component whole-school interventions which involves various aspects of school life (curriculum, interpersonal relationships, activities), such as the Strengthening Evidence base on scHool-based intErventions for pRomoting adolescent health (SEHER) program in India and the Together at School program in Finland, have been proved to be beneficial for prevention from depression [ 87 – 89 ] and psychological problems [ 90 ].

Homework and tests

The association between homework and psychological ill-being outcomes was investigated in four cross-sectional studies and one longitudinal study. Incomplete homework and longer homework durations were associated with a higher risk of anxiety symptoms [ 91 , 92 ], negative emotions [ 93 – 95 ] and even psychological distress in adulthood [ 96 ].

Innumerable exams during the educational process starting from primary schools may lead to increased anxiety and depression levels [ 97 , 98 ], particularly among senior students preparing for college entrance examinations [ 99 ]. Students with higher test scores had a lower probability to have emotional and behavioral problems [ 100 ], in comparison with students who failed examinations [ 93 , 101 ]. Depression and test anxiety were found to be highly correlated [ 102 ]. In terms of psychological well-being outcomes, findings were consistent in the negative associations between student test anxiety and self-esteem/life-satisfaction levels [ 103 , 104 ]. Regarding intervention studies, adolescent students at a high risk of test anxiety benefited from CBT or attention training by strengthening sense of control and meta-cognitive beliefs [ 105 , 106 ]. However, more knowledge about the criteria for an upcoming test was not related to anxiety levels during lessons [ 107 ].

Interpersonal relationships

School-based interpersonal (student–student or student–teacher) relationships are also important to student mental health. Low support from schoolmates/teachers and negative interpersonal events were reported to be associated with psychosomatic health complaints [ 108 – 113 ]. In contrast, positive interpersonal relationships in schools could promote emotional well-being [ 114 – 117 ] and reduce depressive symptoms in students [ 118 – 120 ].

Student–teacher relationships

Negative teaching behaviors were associated with negative affect [ 121 , 122 ] and low self-efficacy [ 123 ] among primary and high school students. Student–teacher conflicts at the beginning of the school year were associated with higher anxiety levels in students at the end of the year, and high-achieving girls were most susceptible to such negative associations [ 124 ]. Higher levels of perceived teachers’ support were correlated with decreased risks of depression [ 125 ], mental health problems [ 126 ] as well as increased positive affect [ 127 , 128 ] and improved mental well-being [ 129 , 130 ]. Better student–teacher relationships were positively associated with self-esteem/efficacy [ 131 ], while negatively associated with the risks of adolescents’ externalizing behaviors [ 132 ] among secondary school students. Longitudinal studies demonstrated that high intimacy levels between students and teachers were correlated with reduced emotional symptoms [ 133 ] and increased life-satisfaction among students [ 134 ]. In addition, more respect to teachers in 10th grade students was associated with higher self-efficacy and lower stress levels 1 year later [ 135 ].

A growing body of research focused on the issue of how to increase positive interactions between teachers and students in teaching practices. Actually, interventions on improving teaching skills to promote a positive classroom atmosphere could potentially benefit children, especially those experiencing a moderate to high level of risks of mental health problems [ 136 , 137 ].

Student–student relationships

Findings were consistent in considering the positive peer relationship as a protective factor against internalizing and externalizing behaviors [ 138 – 142 ], depression [ 143 – 145 ], anxiety [ 146 ], self-harm [ 147 ] and suicide [ 148 ], and as a favorable factor for positive affect [ 149 , 150 ], increased happiness [ 151 ], self-efficacy [ 152 ], optimism [ 153 , 154 ] and mental well-being [ 155 ]. In contrast, peer-hassles, friendlessness, negative peer-beliefs, peer-conflicts/isolation and peer-rejection, have been identified in the development of psychological distress among students [ 141 , 143 , 149 , 156 – 165 ].

As schools and classrooms are common settings to build peer relationships, student social skills to enhance the student–student relationship can be incorporated into school education. Training of interpersonal skills among secondary school students with depressive symptoms appeared to be effective in decreasing adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms [ 166 ]. In addition, recent studies also identified the effectiveness of small-group learning activities in the cognitive development and mental health promotion among students [ 87 – 90 , 167 ].

Physical activity in school

Moderate-to-high-intensity physical activity during school days has been confirmed to benefit children and adolescents in relation to various psychosocial outcomes, such as reduced symptoms of depression [ 168 ], emotional problems [ 169 ] and mental distress [ 170 ] as well as improved self-efficacy [ 171 ] and mental well-being [ 172 , 173 ]. In addition, participation in physical education (PE) at least twice a week was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of suicidal ideation and stress [ 174 ].

A variety of school‐based physical activity interventions or lessons have been proposed in previous studies to promote physical activity levels and psychosocial fitness in students, including integrating physical activities into classroom settings [ 175 – 178 ], assigning physical activity homework [ 178 ], physically-active academic lessons [ 179 , 180 ] as well as an obligation of ensuring the participation of various kinds of sports (such as aerobic exercises, resistance exercises, yoga) in PE lessons [ 181 – 192 ]. Although the effectiveness of these proposed physical activity interventions was not consistent, physical education is suggested to implement sustainably as other academic courses with special attention.

After-school activities

Several cross-sectional studies have synthesized evidence on the positive effects of leisure-time physical activity against student depression, anxiety, stress, and psychological distress [ 193 – 199 ]. Extracurricular sport participation (such as sports, dance, and martial arts) could foster perceived self-efficacy, self-esteem, improve mental health status [ 200 – 203 ], and reduce emotional problems [ 204 ] and depressive symptoms [ 205 ]. Participation in team sports was more strongly related to beneficial mental health outcomes than individual sports, especially in high school girls [ 199 ]. Other forms of organized activities, such as youth organizations and arts, have also been demonstrated to benefit self-esteem [ 201 ], self-worth [ 206 ], satisfaction with life and optimism [ 207 , 208 ].

However, different types of after-school activities may result in different impacts on student mental health. Previous studies demonstrated that students participating in after-school programs of yoga or sports had better well-being and self-efficacy [ 209 ], and decreased levels of anxiety [ 210 ] and negative mood [ 211 ], while another study showed that the after-school yoga program induced no significant changes in levels of depression, anxiety and stress among students [ 212 ]. Inconsistent findings on the effects of participation in art activities on student mental health were also reported [ 213 , 214 ]. Another study also highlighted the benefits of after-school clubs, demonstrating an improvement in socio-emotional competencies and emotional status, and sustained effects at 12-month follow-up [ 215 ].

Based on the potential importance of the five school-based factors identified in student mental development, a multi-component school educational model is therefore proposed to conceptualize the five school-based dimensions (including curriculum, homework and tests, interpersonal relationships, physical activity, and after-school activities) for K-12 students to promote their mental health (Fig. 4 ). The interrelationships among the five dimensions and cross-cultural comparisons are further discussed as follows in a holistic way.

The multi-component school educational model is proposed to conceptualize the five school-based dimensions (including curriculum set, homework and tests, physical activity, interpersonal relationships and after-school activities) for K-12 students to promote student mental health

Comprehensive understanding of K-12 school educational models: the reciprocal relationships among factors

Students’ experiences in the school educational context are dynamic processes which englobe a variety of educational elements (such as curriculum, homework, tests) and social elements (such as interpersonal relationships and social activities in schools). Based on the educational model proposed in this review, these educational/social elements are closely related and interact with each other, which play an important role in students’ psychosocial development.

Being aware of this, initiatives aimed to improve student social and emotional competencies may certainly impact student psychological well-being, at least in part, in a way of developing supportive relationships between teachers-students or between peers [ 35 , 89 ]. On the other hand, the enhancement of interpersonal relationships at school could serve as a potent source of motivation for student academic progress so as to further promote psychological well-being [ 131 , 132 ]. In addition, school education reforms intended to provide pupils with more varied teaching and learning practices to promote supportive interpersonal relationships between students and teachers or between peers, such as education programs outside the classroom [ 82 ], cooperative learning [ 167 ] and adaptive classroom management [ 136 , 137 ], have also been advocated among nations recently.

Our findings also suggested that participation in non-academic activities was an important component of positive youth development. Actually, these school-based activities in different contexts also require teacher–student interactions or peer interactions. Social aspects of physical activities have been proposed to strengthen relationship-building and other interpersonal skills that may additionally protect students against the development of mental health problems [ 130 , 203 ]. Among various types of sports, team sports seemed to be associated with more beneficial outcomes compared with individual sports due to the social aspect of being part of a team [ 194 , 199 ]. Participation in music, student council, and other clubs/organizations may also provide students with frequent connections with peers, and opportunities to build relationships with others that share similar interests [ 201 ]. Further, frequent and supportive interactions with teachers and peers in sports and clubs may promote student positive views of the self and encourage their health-promoting behaviors (such as physical activities).

However, due to increasing academic pressure, children have to spend a large amount of time on academic studies, and inevitably displace time on sleep, leisure, exercises/sports, and extracurricular activities [ 92 ]. Although the right amount of homework may improve school achievements [ 216 ] and higher test scores may help prevent students from mental distress [ 100 – 102 ], over-emphasis on academic achivements may lead to elevated stress levels and poor health outcomes ultimately. The anxiety specifically related to academic achievement and test-taking at school was frequently reported among students who felt pressured and overwhelmed by the continuous evaluation of their academic performance [ 98 , 103 , 104 ]. In such high-pressure academic environments, strategies to alleviate the levels of stress among students should be incorporated into intervention efforts, such as stress management skill training [ 77 – 79 ], CBT-based curriculum [ 62 , 64 , 66 , 105 ], and attention training [ 106 ]. Therefore, school supportive policies that allow students continued access to various non-academic activities as well as improve their social aspect of participation may be one fruitful avenue to promote student well-being.

Cross-cultural differences in K-12 educational models among different nations and societies

As we reviewed above, heavy academic burden exists as an important school-related stressor for students [ 91 , 92 , 94 – 96 ], probably due to excessive examinations [ 97 – 99 ] and unsatisfactory academic performance [ 100 – 102 ]. Actually, extrinsic cultural factors significantly impact upon student academic burden. In most countries, college admission policies affect the entire ecological system of K-12 education, because success in life or careers is determined by examination performance to a large extent [ 217 ]. The impacts of heavy academic burden may be greatest in Asian cultures where more after-school time of students is spent on homework, exam preparations, and extracurricular classes for academic improvement (such as in Korea, Japan, China and Singapore) [ 92 , 95 , 218 ]. As a consequence, the high proportion of adolescents fall in the “academic burnout group” in Asian countries [ 219 ], which highlights the need to take further measures to combat the issue. As an issue of concern, the “double reduction” policy has been implemented nationwide in China since 2021, being aimed to relieve students of excessive study burden, and the effects of the policy are anticipated but remain unknown up to now.

Other factors such as school curriculum and extra-curricular commitments, vary among societies and nations and may explain the cross-cultural differences in educational models [ 220 ]. For example, in Finland, the primary science subject is as important as mathematics or reading, while Chinese schools often lack time to arrange a sufficient number of science courses [ 221 ], which could be explained by different educational traditions of the two countries. In addition, approximately 75% of high schools in Korea failed to implement national curriculum guidelines for physical education (150 min/week), instead replacing that time with self-guided study to prepare for university admission exams [ 174 ]. In terms of the arrangement of the after-school time, Asian students spend most of their after-school time on private tutoring or doing homework [ 222 ], 2–3 times longer than the time spent by adolescents in most western countries/cities [ 92 ]. However, according to our analyses and summaries, most intervention studies targeting the improvement of mental health of students by school education were conducted in western countries (Fig. 2 ), suggesting that special attention needs to be paid to the students’ mental health issue on campus, especially in countries where students have heavy study-loads. Merits of the different educational traditions also need to be considered in the designs of educational models among different countries.

Strengths and limitations

This study focuses on an interdisciplinary topic covering the fields of developmental behavioral pediatrics and education, and the establishment of appropriate school educational models is teamwork involving multiple disciplines including pediatrics, prevention, education, services and policy. Although there are lots of studies focusing on a particular factor in school educational processes to promote student mental health, comprehensive analysis/understanding on multi-component educational model is lacking, which is important and urgently needed for the development of multi-dimensional educational models/strategies. Therefore, we included a wide range of related studies, summarized a comprehensive understanding of the evidence base, and discussed the interrelationships among the components/factors of school educational models and the cross-cultural gaps in K-12 education across different societies, which may have significant implications for future policy-making.

Some limitations also exist and are worth noting. First, this review used the method of the scoping review which adopted a descriptive approach, rather than the meta-analysis or systematic review which provided a rigorous method of synthesizing the literature. Under the subject (appropriate school education model among K-12 students) of this scoping review, multiple related topics (including curriculum, homework and tests, physical activities, interpersonal relationships and after-school activities) were included rather than one specific topic. Therefore, we consider that the method of the scoping-review is appropriate, given that the aim of this review is to chart or map the available literature on a given subject rather than answering a specific question by providing effect sizes across multiple studies. Second, we limited the study search within recent 5 years. Although we consider that the fields involved in this scoping review change quickly with the acquisition of new knowledge/information in recent 5 years, limiting the literature search within recent 5 years may make us miss some related but relatively old literature. Third, we only included studies disseminated in English or Chinese, which may limit the generalizability of our results to other non-English/Chinese speaking countries.

This scoping review has revealed that the K-12 schools are unique settings where almost all the children and adolescents can be reached, and through which existing educational components (such as curriculum, homework and tests, physical activities, interpersonal relationships and after-school activities) can be leveraged and integrated to form a holistic model of school education, and therefore to promote student mental health. In future, the school may be considered as an ideal setting to implement school-based mental health interventions. Our review suggests the need of comprehensive multi-component educational model, which involves academic, social and physical factors, to be established to improve student academic achievement and simultaneously maintain their mental health.

However, questions still remain as to what is optimal integration of various educational components to form the best model of school education, and how to promote the wide application of the appropriate school educational model. Individual differences among students/schools and cross-cultural differences may need to be considered in the model design process.

Acknowledgements

We thank the librarian of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine for their help.

Abbreviations

Author contributions.

JX conceived the scoping review, supervised the review process and reviewed the manuscript. TY conducted study selection and data extraction, charted, synthesized the data, and drafted the manuscript. YJ conducted study selection and data extraction. XG, YZ and HH conducted data extraction. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 81974486, 81673189) (to Jian Xu), Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (20172016) (to Jian Xu), Shanghai Sailing Program (21YF1451500) (to Hui Hua).

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

Is Homework Necessary? Education Inequity and Its Impact on Students

The Problem with Homework: It Highlights Inequalities

How much homework is too much homework, when does homework actually help, negative effects of homework for students, how teachers can help.

Schools are getting rid of homework from Essex, Mass., to Los Angeles, Calif. Although the no-homework trend may sound alarming, especially to parents dreaming of their child’s acceptance to Harvard, Stanford or Yale, there is mounting evidence that eliminating homework in grade school may actually have great benefits , especially with regard to educational equity.

In fact, while the push to eliminate homework may come as a surprise to many adults, the debate is not new . Parents and educators have been talking about this subject for the last century, so that the educational pendulum continues to swing back and forth between the need for homework and the need to eliminate homework.

One of the most pressing talking points around homework is how it disproportionately affects students from less affluent families. The American Psychological Association (APA) explained: