The Impact of the 14th Amendment on American Citizenship

This essay is about the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1868, which reshaped citizenship and civil rights. It established that anyone born or naturalized in the U.S. is a citizen and guaranteed equal protection under the law. The Amendment also introduced the concept of due process, safeguarding individual rights against arbitrary state actions. It laid the groundwork for significant civil rights legislation and Supreme Court decisions, addressing racial segregation, gender equality, LGBTQ rights, and the rights of undocumented immigrants.

How it works

14 is ? Amendment to Constitution of the united states, ratified in 1868, stands how a central landmark in American legal history, deeply forming the landscape of citizenship and civil laws. Born out of consequence of Civil War and abolition of slave, this amendment appealed to the critical problems of citizenship, even defence in accordance with a right, and the proper process, marking substantial departure from previous constitutional structures.

Central to his terms is a concept of citizenship of inalienable right, confirming, that anybody was born or naturalized in the united states is a citizen, independent of race, ethnic belonging, whether condition precedent of enslavement.

This principle not only coded status of citizenship of the once enslaved individuals but and founded foundation for determination of the American identity, concludes moreover. By the guarantee of even protection of rights, 14 – ? Amendment aimed to dismantle discriminatory state practices and guarantee, that all citizens enjoy the same main rights and freedoms.

In addition, an amendment presented the concept of the independent proper process that forbids to the states privation of arbitrary face of life, freedoms, whether the state without the proper process of right. This supply assisted to the guard of individual rights against an arbitrary state action and broadened through some time, to contain the wide row of civil liberties, by the way right on confidentiality and freedom of expression.

In the kingdom of civil laws, 14 – ? Amendment provided a constitutional structure for the later legislation directed in a fight against a pedigree segregation and discrimination. Then put foundation for the greatest Court decisions of frontier landmark for example Brown v. Rule of Education (1954), that declared a segregation in public schools unconstitutional, and Loving v. of Virginia (1967), that brought down rights, what forbids interpedigree shortage.

After his direct operating on pedigree equality, 14 – ? Amendment prolongs to philosophize in modern legal debates concerning gender equality, rights for Lgbtq, and rights for the undocumented immigrants. His principles of the even guard and proper process serve as native stones for judicial interpretation and legislative action in addressing of development of social norms and calls.

A? 14 – ? Amendment undoubtedly extended possibility of citizenship and civil laws in the united states, his implementation was not without a discussion and strong debates. An affirmative action goes out for example, voting right, and politics of immigration removes strong tension between the constitutional guarantees of even defence and realities of systematic inequalities.

Upon completion, 14 – ? Amendment becomes the native stones of the American constitutional law, fundamentally changing mutual relations between an individual and state, laying foundation for society, moreover concludes and just. His principle of citizenship, even defence, and the proper process prolong to form legal conversation and social progress, guaranteeing, that promise of freedom and justice for all bits and pieces leading principle of the American experiment.

Cite this page

The Impact of the 14th Amendment on American Citizenship. (2024, Jun 28). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-the-14th-amendment-on-american-citizenship/

"The Impact of the 14th Amendment on American Citizenship." PapersOwl.com , 28 Jun 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-the-14th-amendment-on-american-citizenship/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Impact of the 14th Amendment on American Citizenship . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-the-14th-amendment-on-american-citizenship/ [Accessed: 25 Oct. 2024]

"The Impact of the 14th Amendment on American Citizenship." PapersOwl.com, Jun 28, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-the-14th-amendment-on-american-citizenship/

"The Impact of the 14th Amendment on American Citizenship," PapersOwl.com , 28-Jun-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-the-14th-amendment-on-american-citizenship/. [Accessed: 25-Oct-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Impact of the 14th Amendment on American Citizenship . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-the-14th-amendment-on-american-citizenship/ [Accessed: 25-Oct-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution Essay

Introduction.

- Interpretation of the 14th amendment

Affirmative action

This amendment was approved on July 1868. The amendment contained two important clauses that marked the history of Civil rights movement in the US. These are the Equal protection clause and the Due Process clause.

The former guaranteed equal protection of the law while the latter protected individuals from deprivation of life, liberty and property by the state without the due process of law. This article looks into the various interpretations given to the Fourteenth Amendment, limitations to its applications and the affirmative action.

Interpretation of the 14 th amendment

The problem that faced the court was in determining what could qualify as equal protection. The first attempt to interpret the Equal protection clause was made in the infamous case of Plessy Vs Ferguson (1896) , which advocated for racial segregation. Justice Brown was concerned with the reasonableness of the clause.

He argued that when the court is reviewing state legislation it should consider regulation of public order and the tradition or custom of the people. “In short, the Court created a very lenient standard when reviewing state legislation: If a statute promotes order or can be characterized as a tradition or custom… the statute meets the requirements of the clause” (Peter, 1998, Par 3).

In Brown Vs Board of Education (1954) however, the Equal Protection clause was given a new meaning. Justice Earl Warren found that segregated facilities did not amount to equal protection in law. He stated:

“…the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others…are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment” (Brown Vs Board of Education, 1954).

Hernandez v. Texas (1954) the Court found that the Equal Protection clause to apply to not only whites and blacks but also other races and ethnic groups. Among these, other races were the Mexican-Americans. Since Brown case, women and illegitimate children have been included in the Equal Protection Clause.

“The Supreme Court accepted the concept of distinction by class, that is, between “white” and Hispanic, and found that when laws produce unreasonable and different treatment on such a basis, the constitutional guarantee of equal protection is violated” (Carl 1982. Par.2).

The Due Process Clause was not only meant to protect basic procedural rights but also substantive rights. In the case of Gitlow Vs New York (1925) , protection of press from abridgement by the legislature was held to be some of the fundamental freedoms protected by the ‘due process’ clause of the fourteenth Amendment from infringement by the state. Here it was dealing with the substantive rights incorporated in the bill of rights.

However, the decision in Muller Vs Oregon (1908), showed that the state could restrict working hours of women if doing so was in their best interest. This decision was made in due regard to the physical health of a woman. It was held that the physical role of women in childbirth and their social role in the society is an issue of public interest permitting the state to regulate their working hours notwithstanding the ‘due process’ clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Even though it offered a starting point, the Fourteenth Amendment was seen not to be enough to curb discrimination and racial segregation. More positive measures were needed to protect minority groups in the US.

“Affirmative Action refers to a set of practices undertaken… to go beyond non-discrimination, with the goal of actively improving the economic status of minorities and women with regard to employment, education, and business ownership and growth” (Holzer & Neumark 2005, Par. 1).

Affirmative Action was first introduced by President John F. Kennedy in the 1961 Executive Order 10925. Thereafter, several more orders were passed to deal with discrimination in employment. Other laws dealing with equal protection were subsequently enacted to outlaw discrimination such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Title II of the Act prohibited discrimination in public accommodations while title IV prohibited race and sex discrimination in employment.

Courts too have joined hands in the fight. For example in Davis vs. Bakke (1978) , where the court found that Bakke had been denied equal protection of the law by the University of California by being refused admission in the school even though his grades were better than the minority’s admitted. This was done in line with a two-track admission system for blacks and whites. Even thought the decision overruled the affirmative action policy, it was viewed as a victory to proponents of affirmative action because it was a fight against racial segregation.

Affirmative action-together with anti-discrimination laws and legislation-has rendered rights of minority groups in the labor market as well as public academic institutions more apparent. Therefore we cannot bow to the critics propositions that affirmative action promotes discrimination and racism.

“Laws barring race- or sex-conscious behavior in hiring, promotions, and discharges are likely to undermine not only explicit forms of Affirmative Action, but also any prohibitions of discrimination that rely on disparate impact analyses for their enforcement” (Holzer and Neumark, 2006, Par, 11).

The Fourteenth amendment has been classified as the most far-reaching amendment in the history of the US constitution especially to the minority groups. “The Fourteenth Amendment itself was the fruit of a necessary and wise solution for a comparable problem” (Howard 2000).

It came at a time when civil rights movements were at the peak and has contributed significantly to the redemption of minority from past discriminatory activities. It created awareness to the whole world on the injustices of racial segregation and prompted the public to take corrective measures, which have no doubt yielded a lot of success.

Brown V Board of Education. (1945). Massive Resistance” to Integration . Web.

Carl. V. (1982). Allsup, Hernandez V state of Texas . Texas. Texas State Historical Association.

Gitlow V. New York . (2011). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Web.

Holzer H. and Neumark D. (2006). Journal of Policy Analysis and Management: Affirmative Action: What do we know? Published by Urban Institute.

Howard. N.M. (2000). The Amendment that Refused to Die: Equality and Justice Deferred: The History of the Fourteenth Amendment. Madison Books.

Peter, M. (1998). Princeton university law Journals: Past and future of Affirmative action Volume I. Issue 2 Springs. Web.

- Argument for Measures to Control Illegal Immigration

- Characteristics of a Failed State: Pakistan

- Rethinking Women’s Substantive Representation

- The First, Fourth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments

- Tests of Controls and Substantive Audit Test

- Should Politicians Resign Due to Sex Scandals?

- Smoking Ban in New York

- Religious, Governmental and Social Views on Same-Sex Marriage

- Thinking Government: Conservatism, Liberalism and Socialism in Post World War II Canada

- Chinese Censorship Block Chinese People from Creativity

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 10). The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-fourteenth-amendment-to-the-us-constitution/

"The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution." IvyPanda , 10 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-fourteenth-amendment-to-the-us-constitution/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution'. 10 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution." October 10, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-fourteenth-amendment-to-the-us-constitution/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution." October 10, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-fourteenth-amendment-to-the-us-constitution/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution." October 10, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-fourteenth-amendment-to-the-us-constitution/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Can you pass the Citizenship Test? Visit this page to test your civics knowledge!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Elementary Curriculum

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Spanish Influence on American History

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Primary Sources on Slavery Winter 2004

Past Issues

71 | The Jewish Legacy in American History | Summer 2024

70 | World War II: Portraits of Service | Spring 2024

69 | The Reception and Impact of the Declaration of Independence, 1776-1826 | Winter 2023

68 | The Role of Spain in the American Revolution | Fall 2023

67 | The Influence of the Declaration of Independence on the Civil War and Reconstruction Era | Summer 2023

66 | Hispanic Heroes in American History | Spring 2023

65 | Asian American Immigration and US Policy | Winter 2022

64 | New Light on the Declaration and Its Signers | Fall 2022

63 | The Declaration of Independence and the Long Struggle for Equality in America | Summer 2022

62 | The Honored Dead: African American Cemeteries, Graveyards, and Burial Grounds | Spring 2022

61 | The Declaration of Independence and the Origins of Self-Determination in the Modern World | Fall 2021

60 | Black Lives in the Founding Era | Summer 2021

59 | American Indians in Leadership | Winter 2021

58 | Resilience, Recovery, and Resurgence in the Wake of Disasters | Fall 2020

57 | Black Voices in American Historiography | Summer 2020

56 | The Nineteenth Amendment and Beyond | Spring 2020

55 | Examining Reconstruction | Fall 2019

54 | African American Women in Leadership | Summer 2019

53 | The Hispanic Legacy in American History | Winter 2019

52 | The History of US Immigration Laws | Fall 2018

51 | The Evolution of Voting Rights | Summer 2018

50 | Frederick Douglass at 200 | Winter 2018

49 | Excavating American History | Fall 2017

48 | Jazz, the Blues, and American Identity | Summer 2017

47 | American Women in Leadership | Winter 2017

46 | African American Soldiers | Fall 2016

45 | American History in Visual Art | Summer 2016

44 | Alexander Hamilton in the American Imagination | Winter 2016

43 | Wartime Memoirs and Letters from the American Revolution to Vietnam | Fall 2015

42 | The Role of China in US History | Spring 2015

41 | The Civil Rights Act of 1964: Legislating Equality | Winter 2015

40 | Disasters in Modern American History | Fall 2014

39 | American Poets, American History | Spring 2014

38 | The Joining of the Rails: The Transcontinental Railroad | Winter 2014

37 | Gettysburg: Insights and Perspectives | Fall 2013

36 | Great Inaugural Addresses | Summer 2013

35 | America’s First Ladies | Spring 2013

34 | The Revolutionary Age | Winter 2012

33 | Electing a President | Fall 2012

32 | The Music and History of Our Times | Summer 2012

31 | Perspectives on America’s Wars | Spring 2012

30 | American Reform Movements | Winter 2012

29 | Religion in the Colonial World | Fall 2011

28 | American Indians | Summer 2011

27 | The Cold War | Spring 2011

26 | New Interpretations of the Civil War | Winter 2010

25 | Three Worlds Meet | Fall 2010

24 | Shaping the American Economy | Summer 2010

23 | Turning Points in American Sports | Spring 2010

22 | Andrew Jackson and His World | Winter 2009

21 | The American Revolution | Fall 2009

20 | High Crimes and Misdemeanors | Summer 2009

19 | The Great Depression | Spring 2009

18 | Abraham Lincoln in His Time and Ours | Winter 2008

17 | Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Era | Fall 2008

16 | Books That Changed History | Summer 2008

15 | The Supreme Court | Spring 2008

14 | World War II | Winter 2007

13 | The Constitution | Fall 2007

12 | The Age Of Exploration | Summer 2007

11 | American Cities | Spring 2007

10 | Nineteenth Century Technology | Winter 2006

9 | The American West | Fall 2006

8 | The Civil Rights Movement | Summer 2006

7 | Women's Suffrage | Spring 2006

6 | Lincoln | Winter 2005

5 | Abolition | Fall 2005

4 | American National Holidays | Summer 2005

3 | Immigration | Spring 2005

2 | Primary Sources on Slavery | Winter 2004

1 | Elections | Fall 2004

The Reconstruction Amendments: Official Documents as Social History

By eric foner.

Like other Radical Republicans, Stevens believed that Reconstruction was a golden opportunity to purge the nation of the legacy of slavery and create a "perfect republic," whose citizens enjoyed equal civil and political rights, secured by a powerful and beneficent national government. In his speech on June 13 he offered an eloquent statement of his political dream—"that the intelligent, pure and just men of this Republic . . . would have so remodeled all our institutions as to have freed them from every vestige of human oppression, of inequality of rights, of the recognized degradation of the poor, and the superior caste of the rich." Stevens went on to say that the proposed amendment did not fully live up to this vision. But he offered his support. Why? "I answer, because I live among men and not among angels." A few moments later, the Fourteenth Amendment was approved by the House. It became part of the Constitution in 1868. The Fourteenth Amendment did not fully satisfy the Radical Republicans. It did not abolish existing state governments in the South and made no mention of the right to vote for blacks. Indeed it allowed a state to deprive black men of the suffrage, so long as it suffered the penalty of a loss of representation in Congress proportionate to the black percentage of its population. (No similar penalty applied, however, when women were denied the right to vote, a provision that led many advocates of women’s rights to oppose ratification of this amendment.) Nonetheless, the Fourteenth Amendment was the most important constitutional change in the nation’s history since the Bill of Rights. Its heart was the first section, which declared all persons born or naturalized in the United States (except Indians) to be both national and state citizens, and which prohibited the states from abridging their "privileges and immunities," depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or denying them "equal protection of the laws." In clothing with constitutional authority the principle of equality before the law regardless of race, enforced by the national government, this amendment permanently transformed the definition of American citizenship as well as relations between the federal government and the states, and between individual Americans and the nation. We live today in a legal and constitutional system shaped by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment was one of three changes that altered the Constitution during the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865, irrevocably abolished slavery throughout the United States. The Fifteenth, which became part of the Constitution in 1870, prohibited the states from depriving any person of the right to vote because of race (although leaving open other forms of disenfranchisement, including sex, property ownership, literacy, and payment of a poll tax). In between came the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which gave the vote to black men in the South and launched the short-lived period of Radical Reconstruction, during which, for the first time in American history, a genuine interracial democracy flourished. "Nothing in all history," wrote the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, equaled "this . . . transformation of four million human beings from . . . the auction-block to the ballot-box." These laws and amendments reflected the intersection of two products of the Civil War era—a newly empowered national state and the idea of a national citizenry enjoying equality before the law. These legal changes also arose from the militant demands for equal rights from the former slaves themselves. As soon as the Civil War ended, and in some places even before, blacks gathered in mass meetings, held conventions, and drafted petitions to the federal government, demanding the same civil and political rights as white Americans. Their mobilization (given moral authority by the service of 200,000 black men in the Union Army and Navy in the last two years of the war) helped to place the question of black citizenship on the national agenda. The Reconstruction Amendments, and especially the Fourteenth, transformed the Constitution from a document primarily concerned with federal-state relations and the rights of property into a vehicle through which members of vulnerable minorities could stake a claim to substantive freedom and seek protection against misconduct by all levels of government. The rewriting of the Constitution promoted a sense of the document’s malleability, and suggested that the rights of individual citizens were intimately connected to federal power. The Bill of Rights had linked civil liberties and the autonomy of the states. Its language—"Congress shall make no law"—reflected the belief that concentrated power was a threat to freedom. Now, rather than a threat to liberty, the federal government, declared Charles Sumner, the abolitionist US senator from Massachusetts, had become "the custodian of freedom." The Reconstruction Amendments assumed that rights required political power to enforce them. They not only authorized the federal government to override state actions that deprived citizens of equality, but each ended with a clause empowering Congress to "enforce" them with "appropriate legislation." Limiting the privileges of citizenship to white men had long been intrinsic to the practice of American democracy. Only in an unparalleled crisis could these limits have been superseded, even temporarily, by the vision of an egalitarian republic embracing black Americans as well as white and presided over by the federal government. Constitutional amendments are often seen as dry documents, of interest only to specialists in legal history. In fact, as the amendments of the Civil War era reveal, they can open a window onto broad issues of political and social history. The passage of these amendments reflected the immense changes American society experienced during its greatest crisis. The amendments reveal the intersection of political debates at the top of society and the struggles of African Americans to breathe substantive life into the freedom they acquired as a result of the Civil War. Their failings—especially the fact that they failed to extend to women the same rights of citizenship afforded black men—suggest the limits of change even at a time of revolutionary transformation. Moreover, the history of these amendments underscores that rights, even when embedded in the Constitution, are not self-enforcing and cannot be taken for granted. Reconstruction proved fragile and short-lived. Traditional ideas of racism and localism reasserted themselves, Ku Klux Klan violence disrupted the Southern Republican party, and the North retreated from the ideal of equality. Increasingly, the Supreme Court reinterpreted the Fourteenth Amendment to eviscerate its promise of equal citizenship. By the turn of the century, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments had become dead letters throughout the South. A new racial system had been put in place, resting on the disenfranchisement of black voters, segregation in every area of life, unequal education and job opportunities, and the threat of violent retribution against those who challenged the new order. The blatant violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments occurred with the acquiescence of the entire nation. Not until the 1950s and 1960s did a mass movement of black southerners and white supporters, coupled with a newly activist Supreme Court, reinvigorate the Reconstruction Amendments as pillars of racial justice. Today, in continuing controversies over abortion rights, affirmative action, the rights of homosexuals, and many other issues, the interpretation of these amendments, especially the Fourteenth, remains a focus of judicial decision-making and political debate. We have not yet created the "perfect republic" of which Stevens dreamed. But more Americans enjoy more rights and freedoms than ever before in our history.

Eric Foner , the DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University, is the author of numerous books on the Civil War and Reconstruction. His most recent book, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (2010), has received the Pulitzer, Bancroft, and Lincoln Prizes.

Suggested Sources

Books and printed materials.

A selection of relevant books by the author of this essay: Foner, Eric. Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. New York: Knopf, 2005.

Foner, Eric. Nothing But Freedom: Emancipation and Its Legacy. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1807. New York: Perennial Classics, 2002.

On the adoption of the Reconstruction Amendments: Maltz, Earl M. Civil Rights, the Constitution, and Congress, 1863–1869 . Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990.

The Reconstruction Amendments’ Debates: The Legislative History and Contemporary Debates in Congress on the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments . Richmond: Commission on Constitutional Government, 1963.

Richards, David A. Conscience and the Constitution: History, Theory, and Law of the Reconstruction Amendments. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

On Thaddeus Stevens: Stevens, Thaddeus. The Selected Papers of Thaddeus Stevens. Beverly Wilson Palmer and Holly Byers Ochoa, eds. 2 vols. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997.

Internet Resources

Yale University’s "Avalon Project" for a multitude of documents related to American legal and constitutional history: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/default.asp

For images of manuscript copies of the amendments, transcripts of their texts, and brief background information, see the National Archives’ "Our Documents" site: http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=40 [Thirteenth Amendment] http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=43 [Fourteenth Amendment] http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=44 [Fifteenth Amendment]

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course, the drafting table.

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

- Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

- Election Teaching Resources

Constitution 101 With Khan Academy

Explore our new course that empowers students to learn the constitution at their own pace..

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, classroom resources by topic, 14th amendment, introduction.

The 14th Amendment wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise of freedom and equality into the Constitution. Ratified after the Civil War, this amendment transformed the Constitution forever and is at the core of a period that many scholars refer to as our nation’s “Second Founding.” Even so, the 14th Amendment remains the focus of many of today’s most important constitutional debates (and Supreme Court cases). In many ways, the history of the modern Supreme Court is largely a history of modern-day battles over the 14th Amendment's meaning. So many of the constitutional cases that Americans care about today turn on the 14th Amendment.

Big Questions

What is the 14th amendment, and what does it say, what core principles does it add to the constitution, how did the 14th amendment transform the constitution, how does the 14th amendment promote equality, how does the 14th amendment protect freedom, what are some areas of ongoing constitutional debate, video: recorded class.

Briefing Document

Video: constitution 101 lecture.

Constitution 101

Module 14: The 14th Amendment: Battles for Freedom and Equality

More Videos

Eric foner: creation and contents of the fourteenth amendment, jeffrey rosen: the 14th amendment's major clauses, tomiko brown nagin: the continuing relevance of the fourteenth amendment., 14th amendment overview video, the black codes: a clip from fourteen, women of reconstruction: a clip from fourteen, additional resources, battles for equality in america: the 14th amendment featuring christopher r. riano.

In this Fun Friday Session, Christopher R. Riano, president of the Center for Civic Education, joins National Constitution Center President and CEO Jeffrey Rosen for a conversation on the 14th Amendment and the battle over its meaning from Reconstruction to the Supreme Court’s landmark decision on marriage equality in Obergefell.

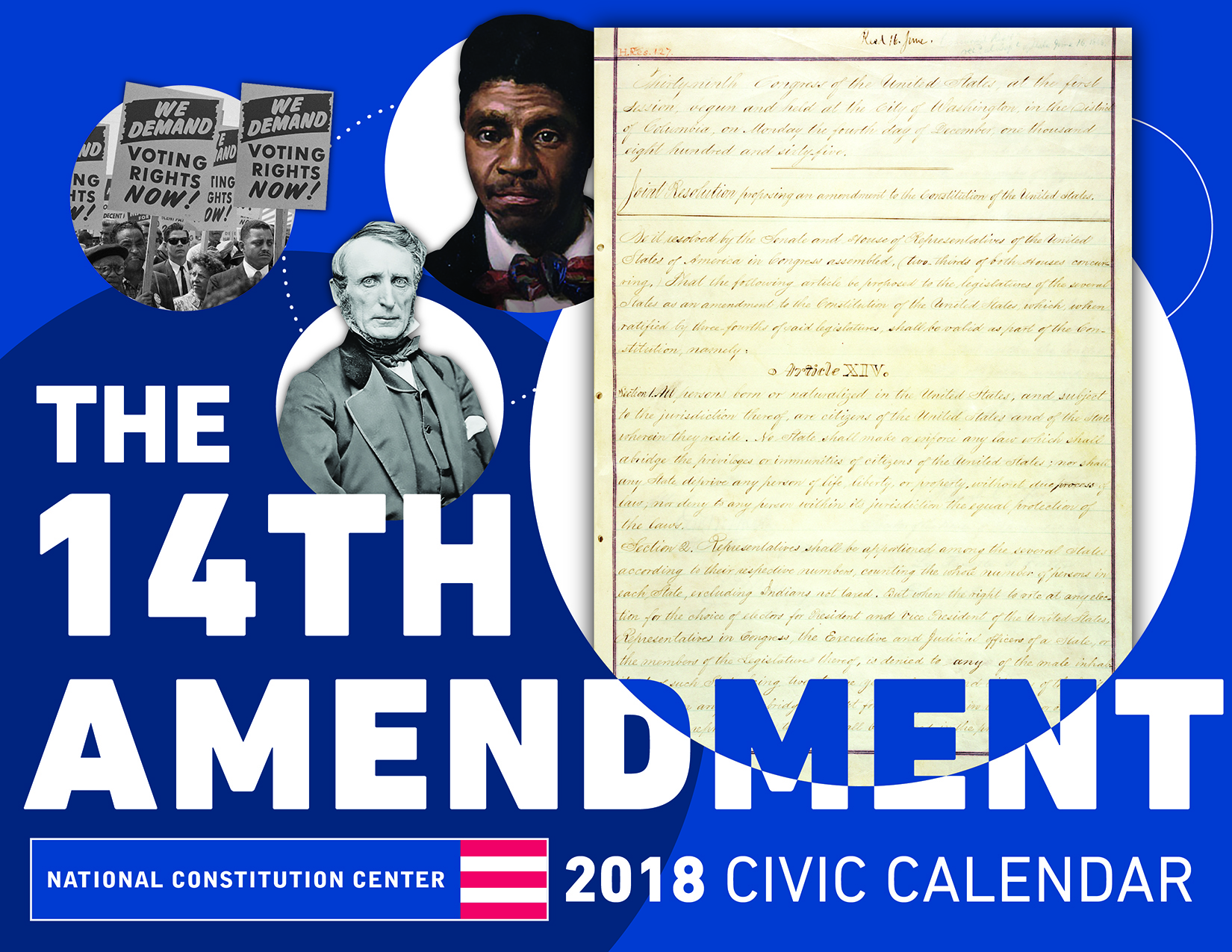

2018 Civic Holiday Calendar: 14th Amendment

To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the 14th Amendment, the Center's 2018 calendar explores its history and legacy.

The Declaration and Frederick Douglass: A Clip From FOURTEEN

In this clip from FOURTEEN , the performance opens with the words of the Declaration of Independence, after which a performer reads an open letter from Douglass to his former slaveholder.

The 39th Congress Debates: A Clip From FOURTEEN

In this clip from FOURTEEN performers use the words of the 39th Congress as they debate the proposed 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

The Emancipation Proclamation: A Clip From FOURTEEN

In this clip from FOURTEEN , a performer embodying President Lincoln reads an excerpt of the Emancipation Proclamation. Another performer reads an 1864 letter written by Annie Davis, an enslaved woman who, upon hearing of the proclamation, seeks President Lincoln’s guidance on if she can freely travel to visit her family.

Classroom Materials

Explore the 14th amendment on the interactive constitution.

- Full Text of the Amendment

- Citizenship Clause Essays

- Privileges or Immunities Clause Essays

- Due Process Clause Essays

- Equal Protection Clause Essays

- Enforcement Clause Essays

- Video: Interactive Constitution Tutorial

Explore 14th Amendment Questions

Plans of Study

Explore key historical documents that inspired the Framers of the Constitution and each amendment during the drafting process, the early drafts and major proposals behind each provision, and discover how the drafters deliberated, agreed and disagreed, on the path to compromise and the final text.

Keep Learning

More from the national constitution center.

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Andrew Johnson and the Civil War Amendments

President Andrew Joh

Lesson Components

- How did President Andrew Johnson interpret the Constitution with respect to restoring the Union after the Civil War?

Students will:

- Trace the constitutional controversies of Andrew Johnson’s presidency.

- Understand Johnson’s constitutional objections to the Fourteenth Amendment and other elements of Reconstruction.

- Evaluate Johnson’s understanding of the Constitution.

Expand Materials Materials

Handout a: andrew johnson and the civil war amendments, handout b: johnson’s first annual message to congress, december 1865, expand more information more information.

To create a context for this lesson, have students complete Constitutional Connection: Slavery and the Constitution .

Expand Prework Prework

Have students read Handout A: Andrew Johnson and the Civil War Amendments and answer the questions.

Expand Warmup Warmup

Show the thematic documentary All Other Persons: Slavery, the Constitution, and the Presidency found at www.youtube.com/watch?v=TmMOvLCCO0c .

Expand Activities Activities

Distribute Handout B: Johnson’s First Annual Message to Congress, December 1865 . Depending on students’ reading skills, you may wish to:

- Have students analyze each section individually.

- Have students work in pairs to analyze each section.

- Have students work in pairs to analyze one section, and then have students jigsaw into new groups to share their responses.

- Project Handout B and go over all the chart sections together.

Expand Wrap Up Wrap Up

Reconvene the class and conduct a large group discussion to answer the questions:

- Why do you think Johnson’s plans for “restoration” failed?

- Were his objections to the forced-ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment legitimate? Why or why not?

- In your opinion, did Johnson understand the Constitution correctly?

Expand Homework Homework

Have students analyze the Fourteenth Amendment and write a brief essay with one of the following thesis statements:

- The Fourteenth Amendment radically altered the Constitution.

- The Fourteenth Amendment merely emphasized principles that were already in the Constitution.

Expand Extensions Extensions

Develop a timeline that shows legislation vetoed by President Johnson. For each law, summarize the following:

- name & date of bill

- purpose of bill

- why Johnson vetoed the bill

- further Congressional action, if any

- outcome of the law, if applicable

Students can begin their research at: www.presidency.ucsb.edu/data/vetoes.php and www.usconstitution.net/pres_veto.html

Student Handouts

Related resources.

The End of Slavery and the Reconstruction Amendments

The interests of Northern and Southern states grew increasingly divergent. Eleven states eventually seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America. After the Civil War, Congress required that the southern states would approve the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments as a condition of their re-entry into the union. The Thirteenth Amendment banned slavery throughout the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to formerly enslaved people and banned states from passing laws that denied the privileges and immunities of citizens, due process, or equal protection of the law. The Fifteenth Amendment extended the right to vote to black men. The Fourteenth Amendment in particular was a dramatic departure from the Founders’ Constitution, and set the stage for dramatic increases in the size, scope, and power of the national government decades later.

Civil War and Reconstruction

Explore the impact the Civil War amendments had on African-Americans during Reconstruction and beyond.

Tenth Period | Reconstruction and Narrative: Amendments and Their Limitations

BRI staff members Kirk Higgins and Rachel Davison Humphries are joined by BRI Teacher Council member Michael Sandstrom and LeeAnna Keith, author of "The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, and the Death of Reconstruction," as they explore meaningful narratives from the Reconstruction time period and their implications today. What role did the Reconstruction amendments, the 13th Amendment, 14th Amendment, and 15th Amendment play in local, state, and federal outcomes of the onset of the Jim Crow?

Liberty and Equality for African Americans During Reconstruction

The Civil War and Reconstruction period produced significant political, economic, and social transformations in the United States, but for African Americans the progress had mixed results at best. The legacy of the Civil War included the central question of what emancipation meant beyond the destruction of the institution of slavery.

Congressional Debate on the 14th Amendment

- February 28, 1866

Introduction

As Republicans were passing the Civil Rights Act of 1866 , they were concerned to make sure that its protection for freedmen would be secure within the Constitution. The 13 th Amendment did not seem to provide Congress with sufficient new powers to protect freedmen and others from the black codes and unequal enforcement of the laws happening under Johnson’s restored state governments. How could the U.S. Constitution be amended to ensure that the state governments provided justice and the protection of rights to all citizens? As the Supreme Court had ruled in Barron v. Baltimore (1833), the original ten amendments to the Constitution limited the power only of Congress, leaving the states free to violate the rights protected in the Bill of Rights or to honor them only with regard to some of their citizens. The issue of protecting the freedmen from state abuses and neglect thus became part of larger deliberations among Republicans about how to correct this defect in the constitutional system. How could the national government protect the rights of individual citizens?

Representative John Bingham (1815-1900), a Republican from Ohio and the principal sponsor of the 14 th amendment , first brought it to the floor in February, 1866. Action on it was postponed after Republicans became leery of its language (reproduced below as part of the speeches on the Amendment), and Congress’s attention turned to the Civil Rights Act. Once that act passed in April 1866, Bingham turned to winning support for a revised amendment that would support the Civil Rights Act specifically and, more broadly, fix what Republicans saw as the defect in the original Constitution. The debates from February and April illuminate the approach to protecting rights found in the 14 th Amendment. The amendment cleared the Senate on June 8, 1866 (33-11) and the House on June 13, 1866 (120-32). It was ratified by three-quarters of the state legislatures on July 28, 1868. Below, selected speeches from key actors in the 14 th Amendment debates are presented after excerpts from amendment in its final adopted form.

Source: 14 th Amendment, Statutes at Large , 39th Congress, 1st Session, 358–59, https://goo.gl/TraZUU ; Congress Debates the 14th Amendment, Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Session, pp. 1083, 1095, 2459, 2462, 2542, 2765.

14 th Amendment

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each state, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the executive and judicial officers of a state, or the members of the legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such state . . . and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such state.

Section 3. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any state legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any state, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Key Speeches on the 14 th Amendment

[Representative John Bingham proposed the following Amendment to the Constitution in February.]

“The Congress shall have the power to make all laws necessary and proper to secure to citizens of each state all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states, and to all persons in the several states equal protection of life, liberty and property.” 1

[Representative Giles W. Hotchkiss, R-NY (1815-1878) moved that Congress postpone consideration of this amendment on February 28, 1866.]

Mr. HOTCHKISS. My excuse for detaining the House is simply that I desire to explain why I shall vote [to postpone consideration, which] may be regarded as inconsistent with my usual votes in this House.

I have no doubt that I desire to secure every privilege and every right to every citizen in the United States that the gentleman who reports this resolution desires to secure. As I understand it, [ Representative Bingham’s ] object in offering this resolution and proposing this amendment is to provide that no State shall discriminate between its citizens and give one class of citizens greater rights than it confers upon another. If this amendment secured that, I should vote very cheerfully for it today; but as I do not regard it as permanently securing these rights, I shall vote to postpone its consideration until there can be a further conference between the friends of the measure, and we can devise some means whereby we shall secure these rights beyond a question.

I understand the amendment as now proposed by its terms to authorize Congress to establish uniform laws throughout the United States upon the subject named, the protection of life, liberty, and property. I am unwilling that Congress shall have any such power. Congress already has the power to establish a uniform rule of naturalization and uniform laws upon the subject of bankruptcy. That is as far as I am willing that Congress shall go. The object of a Constitution is not only to confer power upon the majority, but to restrict the power of the majority and to protect the rights of the minority. It is not indulging in imagination to any great stretch to suppose that we may have a Congress here who would establish such rules in my State as I should be unwilling to be governed by. Should the power of this Government, as the gentleman from Ohio fears, pass into the hands of the rebels, I do not want rebel laws to govern and be uniform throughout this Union.

Mr. BINGHAM. The gentleman will pardon me. The amendment is exactly in the language of the Constitution; that is to say, it secures to the citizens of each of the States all the privileges and immunities of citizens of the several States. It is not to transfer the laws of one State to another State at all. It is to secure to the citizen of each State all the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States in the several States. If the State laws do not interfere, those immunities follow under the Constitution.

Mr. HOTCHKISS. Constitutions should have their provisions so plain that it will be unnecessary for courts to give construction to them; they should be so plain that the common mind can understand them.

The first part of this amendment to which the gentleman alludes, is precisely like the present Constitution; it confers no additional powers. It is the latter clause wherein Congress is given the power to establish these uniform laws throughout the United States. Now, if the gentleman’s object is, as I have no doubt it is, to provide against a discrimination to the injury or exclusion of any class of citizens in any State from the privileges which other classes enjoy, the right should be incorporated into the Constitution. It should be a constitutional right that cannot be wrested from any class of citizens, or from the citizens of any State by mere legislation. But this amendment proposes to leave it to the caprice of Congress; and your legislation upon the subject would depend upon the political majority of Congress, and not upon two thirds of Congress and three fourths of the States.

Now, I desire that the very privileges for which the gentleman is contending shall be secured to the citizens; but I want them secured by a constitutional amendment that legislation cannot override. Then if the gentleman wishes to go further, and provide by laws of Congress for the enforcement of these rights, I will go with him.

. . . . Place these guarantees in the Constitution in such a way that they cannot be stripped from us by any accident, and I will go with the gentleman.

Mr. Speaker, I make these remarks because I do not wish to be placed in the wrong upon this question. I think the gentleman from Ohio [Mr. BINGHAM] is not sufficiently radical in his views upon this subject. I think he is a conservative. [Laughter.] I do not make the remark in any offensive sense. But I want him to go to the root of this matter.

His amendment is not as strong as the Constitution now is. The Constitution now gives equal rights to a certain extent to all citizens. This amendment provides that Congress may pass laws to enforce these rights. Why not provide by an amendment to the Constitution that no State shall discriminate against any class of its citizens; and let that amendment stand as a part of the organic law of the land, subject only to be defeated by another constitutional amendment. We may pass laws here to-day, and the next Congress may wipe them out. Where is your guarantee then?

Let us have a little time to compare our views upon this subject, and agree upon an amendment that shall secure beyond question what the gentleman desires to secure. It is with that view, and no other, that I shall vote to postpone this subject for the present.

[Congress rejected a call to table the amendment but agreed to postpone consideration by a 110-37 vote. 2 On April 30, 1866, members of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction reported to Congress a new 14 th Amendment, substantially the same as the final amendment. Debate began a week later.]

May 8, 1866

Representative Thaddeus Stevens, R-PA:

. . . I can hardly believe that any person can be found who will not admit that every one of these provisions is just. They are all asserted, in some form or other, in our DECLARATION or organic law. 3 But the Constitution limits only the action of Congress, and is not a limitation on the States. This amendment supplies that defect, and allows Congress to correct the unjust legislation of the States, so far that the law which operates upon one man shall operate equally upon all. Whatever law punishes a white man for a crime shall punish the black man precisely in the same way and to the same degree. Whatever law protects the white man shall afford “equal” protection to the black man. Whatever means of redress is afforded to one shall be afforded to all. Whatever law allows the white man to testify in court shall allow the man of color to do the same. These are great advantages over their present codes. Now, different degrees of punishment are inflicted, not on account of the magnitude of the crime, but according to the color of the skin. Now, color disqualifies a man from testifying in courts, or being tried in the same way as white men. I need not enumerate these partial and oppressive laws. Unless the Constitution should restrain them those States will all, I fear, keep up this discrimination, and crush to death the hated freedmen. . . .

Rep. James Garfield, R-OH:

. . . I am glad to see this first section here which proposes to hold over every American citizen, without regard to color, the protecting shield of law. The gentleman who has just taken his seat [Mr. FINCK, D-OH] undertakes to show that because we propose to vote for this section we therefore acknowledge that the civil rights bill was unconstitutional. He was anticipated in that objection by the gentleman from Pennsylvania, [Mr. STEVENS]. The civil rights bill is now a part of the law of the land. But every gentleman knows it will cease to be a part of the law whenever the mad moment arrives when that gentleman’s party comes into power. It is precisely for that reason that we propose to lift that great and good law above the reach of political strife, beyond the reach of the plots and machinations of any party. . . . For this reason, and not because I believe the civil rights bill unconstitutional, I am glad to see that first section here. . . .

May 10, 1866

Representative John Bingham:

. . . The necessity for the first section of this amendment to the Constitution, Mr. Speaker, is one of the lessons that have been taught to your committee and taught to all the people of this country by the history of the past four years of terrific conflict – that history in which God is, and in which He teaches the profoundest lessons to men and nations. There was a want hitherto, and there remains a want now, in the Constitution of our country, which the proposed amendment will supply. What is that? It is the power in the people, in the whole people of the United States, by express authority of the Constitution to do that by congressional enactment which hitherto they have not had the power to do, and have never even attempted to do; that is, to protect by national law the privileges and immunities of all the citizens of the Republic and the inborn rights of every person within its jurisdiction whenever the same shall be abridged or denied by the unconstitutional acts of any State.

. . . This amendment takes from no State any right that ever pertained to it. No State ever had the right, under the forms of law or otherwise, to deny to any freeman the equal protection of the laws or to abridge the privileges or immunities of any citizen of the Republic, although many of them have assumed and exercised the power, and that without remedy. . . .

May 23, 1866

Senator Jacob Howard, R-MI:

. . . It will be observed that this is a general prohibition upon all the States, as such, from abridging the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the United States. That is its first clause, and I regard it as very important. It also prohibits each one of the States from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or denying to any person within the jurisdiction of the State the equal protection of its laws.

The first clause of this section relates to the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States as such, and as distinguished from all other persons not citizens of the United States. It is not, perhaps, very easy to define with accuracy what is meant by the expression, “citizen of the United States.” . . . A citizen of the United States is held by the courts to be a person who was born within the limits of the United States and subject to their laws. . . .

It would be a curious question to solve what are the privileges and immunities of citizens of each of the States in the several States. I do not propose to go at any length into that question at this time. . . . [I]t is certain the clause was inserted in the Constitution for some good purpose. . . . [W]e may gather some intimation of what probably will be the opinion of the judiciary by referring to a case adjudged many years ago in one of the circuit courts of the United States by Judge [Bushrod] Washington. 4 . . . It is the case of Corfield vs. Coryell . . . . Judge Washington says: . . .

The inquiry is, what are the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States? We feel no hesitation in confining these expressions to those privileges and immunities which are in their nature fundamental, which belong of right to the citizens of all free Governments, and which have at all times been enjoyed by the citizens of the several States which compose this Union from the time of their becoming free, independent, and sovereign. What these fundamental principles are it would, perhaps, be more tedious than difficult to enumerate. They may, however, be all comprehended under the following general heads: protection by the Government, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right to acquire and possess property of every kind, and to pursue and obtain happiness and safety, subject nevertheless to such restraints as the Government may justly prescribe for the general good of the whole. The right of a citizen of one State to pass through or to reside in any other State, for purposes of trade, agriculture, professional pursuits, or otherwise; to claim the benefit of the writ of habeas corpus ; to institute and maintain notions of any kind in the courts of the State; to take, hold, and dispose of property, either real or personal, and an exemption from higher taxes or impositions than are paid by the other citizens of the State, may be mentioned as some of the particular privileges and immunities of citizens which are clearly embraced by the general description of privileges deemed to be fundamental, to which may be added the elective franchise, as regulated and established by the laws or constitution of the State in which it is to be exercised. . . .

Such is the character of the privileges and immunities spoken of in the second section of the fourth article of the Constitution. To these privileges and immunities, whatever they may be – for they are not and cannot be fully defined in their entire extent and precise nature – to these should be added the personal rights guaranteed and secured by the first eight amendments of the Constitution; such as the freedom of speech and of the press; the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the Government for a redress of grievances, a right appertaining to each and all the people; the right to keep and to bear arms; the right to be exempted from the quartering of soldiers in a house without the consent of the owner; the right to be exempt from unreasonable searches and seizures, and from any search or seizure except by virtue of a warrant issued upon a formal oath or affidavit; the right of an accused person to be informed of the nature of the accusation against him, and his right to be tried by an impartial jury of the vicinage; and also the right to be secure against excessive bail and against cruel and unusual punishments. . . .

- 1. Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Session, p. 1083. https://goo.gl/j9q7mE

- 2. Tabling would have effectively killed the bill, but postponing consideration meant that it would come up in Congress without a return to the committee.

- 3. By “organic law,” Stevens refers to the fundamental law of the US, written or unwritten. He seems to view the Declaration as establishing this fundamental law later established in the Constitution.

- 4. Bushrod Washington (1762-1829) was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1798 through 1829 and a nephew of George Washington.

Address Before the General Assembly of the State of Georgia

Ex parte milligan, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Coming soon! World War I & the 1920s!

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This essay focuses on the creation of the Fourteenth Amendment and its impact on the founding principles of con-stitutional federalism. My conclusion, in brief, is that although the Fourteenth Amendment dramatically expanded the list of rights the citizens can assert against the states, it does so in a

The Fourteenth Amendment – Constitutional Law Essay. Exclusively available on IvyPanda®. The end of the Civil War led to the defeat of the Confederacy (Ville 179). Abraham Lincoln’s administration declared the slaves free.

This essay is about the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1868, which reshaped citizenship and civil rights. It established that anyone born or naturalized in the U.S. is a citizen and guaranteed equal protection under the law.

This article looks into the various interpretations given to the Fourteenth Amendment, limitations to its applications and the affirmative action.

Explain why the 14th Amendment was added to the Constitution. Identify the core principles in clauses of the 14th Amendment. Summarize how the Supreme Court has interpreted the meaning of the 14th Amendment. Evaluate the effect of the 14th Amendment on liberty and equality.

The Fourteenth Amendment was one of three changes that altered the Constitution during the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865, irrevocably abolished slavery throughout the United States.

The 14th Amendment wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise of freedom and equality into the Constitution. Ratified after the Civil War, this amendment transformed the Constitution forever and is at the core of a period that many scholars refer to as our nation’s “Second Founding.”

Have students analyze the Fourteenth Amendment and write a brief essay with one of the following thesis statements: The Fourteenth Amendment radically altered the Constitution. The Fourteenth Amendment merely emphasized principles that were already in the Constitution.

Why was debate about the 14th Amendment postponed at the end of February 1866? What changes to the amendment were made before its passage? What is the significance of those changes?

The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits a State from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, and from denying to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, but it adds nothing to the rights of one citizen as against another.