Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Anne Frank — Outline For Anne Frank Essay

Outline for Anne Frank Essay

- Categories: Anne Frank Holocaust

About this sample

Words: 513 |

Published: Mar 5, 2024

Words: 513 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 743 words

5 pages / 2265 words

3.5 pages / 1561 words

2 pages / 1008 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Anne Frank

Anne Frank, that young Jewish girl who became such a symbol of strength and hope during the Holocaust, has really captured the hearts of readers everywhere with her amazing diary. In this essay, I'm gonna dive deeper into what [...]

Anne Frank, a young Jewish girl who lived during the Holocaust, has become an iconic figure whose diary has captured the hearts and minds of people all over the world. Her words, written during the two years she and her family [...]

Anne Frank is one of the most well-known figures of the Holocaust and World War II. Her diary, which she kept while in hiding from the Nazis, has become a symbol of hope and resilience in the face of adversity. In this speech, [...]

Anne Frank, a young Jewish girl who lived in hiding during the Holocaust, has become a symbol of resilience and hope for millions of people around the world. Her diary, which she wrote while in hiding, has been a source of [...]

The Diary of Anne Frank is a powerful and poignant account of a young girl's experiences during World War II. As readers, we are given a rare glimpse into the daily life of a Jewish family hiding from the Nazis in Amsterdam. The [...]

Why people so angry? After all, we all love something. The life of 13-year-old Anna was completely carefree, but one day everything changed. Her father - respectful Otto Frank - decided to leave Germany with his family and move [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

Anne Frank: Diary

The Diary of Anne Frank is the first, and sometimes only, exposure many people have to the history of the Holocaust. Meticulously handwritten during her two years in hiding, Anne's diary remains one of the most widely read works of nonfiction in the world. Anne has become a symbol for the lost promise of the more than one million Jewish children who died in the Holocaust.

There are several versions of her diary. Anne herself edited one version of the diary, in hopes of it being published as a book after the war.

The Diary of Anne Frank was published posthumously in 1947 and eventually translated into almost 70 languages.

It became popular after it was adapted for the stage in 1955.

[caption=eaca7d80-459d-43c2-9eed-80702169ab3d] - [credit=eaca7d80-459d-43c2-9eed-80702169ab3d]

The Diary Begins

The house at Prinsengracht 263, where Anne Frank and her family were hidden. Amsterdam, the Netherlands. After 1935.

- Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz

Anne Frank and her family fled Germany after the Nazis seized power in 1933 and resettled in the Netherlands, where her father, Otto, had business connections. The Germans occupied Amsterdam in May 1940, and two years later German authorities with help from their Dutch collaborators began rounding up Jews and ultimately deported them to killing centers.

I n July 1942, Anne, her sister, Margot, her mother, Edith, and her father went into hiding. They huddled into a secret attic apartment behind the office of the family-owned business at 263 Prinsengracht Street, which would eventually hide four Dutch Jews as well.

While in hiding, Anne kept a diary in which she recorded her fears, hopes, and experiences. She received her first diary on her 13th birthday, June 12, 1942. She wrote:

I hope I shall be able to confide in you completely, as I have never been able to do in anyone before, and I hope that you will be a great support and comfort to me. I expect you will be interested to hear what it feels like to hide; well, all I can say is that I don't know myself yet. I don't think I shall ever feel really at home in this house but that does not mean that I loathe it here, it is more like being on vacation in a very peculiar boardinghouse. Rather a mad way of looking at being in hiding perhaps but that is how it strikes me. [July 11, 1942] The fact that we can never go outside bothers me more than I can say, and then I'm really afraid that we'll be discovered and shot, not a very nice prospect, needless to say. [July 11, 1942]

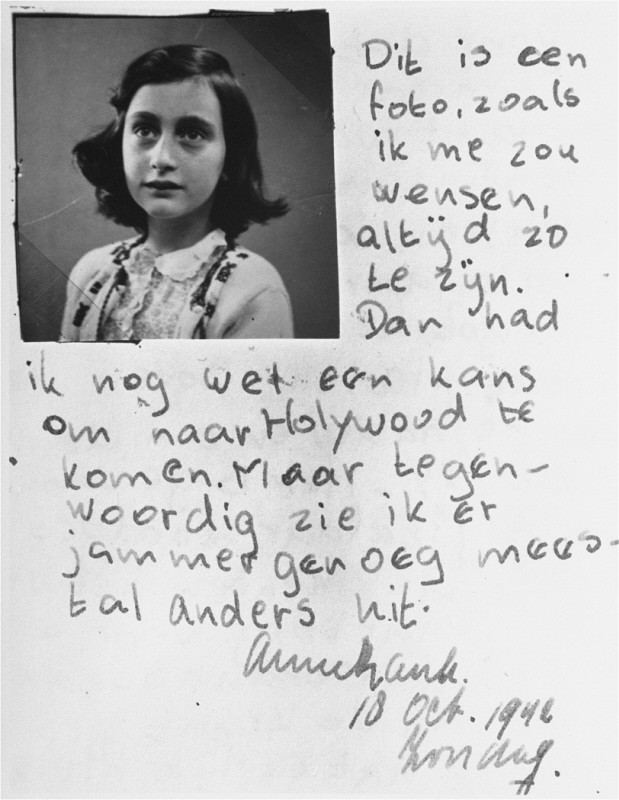

Excerpt from Anne Frank's diary for the date October 10, 1942: "This is a photograph of me as I wish I looked all the time. Then I might still have a chance of getting to Hollywood. But now I am afraid I usually look quite different." Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Anne Frank Stichting

- View Archival Details

Anne also wrote short stories, fairy tales, and essays. In her diary, she reflected on her "pen children," as she called her writings. On September 2, 1943, she began to meticulously copy them into a notebook and added a table of contents so that it would resemble a published book. She gave it the title "Stories and Events from the Annex." Occasionally she read a story to the inhabitants of the annex, and she wrote about her intention to send one of her fairy tales to a Dutch magazine. Increasingly, she expressed her desire to be an author or journalist.

On March 28, 1944, a radio broadcast from the Dutch government-in-exile in London urged the Dutch people to keep diaries, letters, and other items that would document life under German occupation. Prompted by this announcement, Anne began to edit her diary, hoping to publish it after the war under the title "The Secret Annex." From May 20 until her arrest on August 4, 1944, she transferred nearly two-thirds of her diary from her original notebooks to loose pages, making various revisions in the process.

Just imagine how interesting it would be if I were to publish a romance of the "Secret Annex." The title alone would be enough to make people think it was a detective story. But, seriously, it would be quite funny 10 years after the war if we Jews were to tell how we lived and what we ate and talked about here. Although I tell you a lot, still, even so, you only know very little of our lives. [March 29, 1944]

On April 17, 1944, Anne began writing in what turned out to be her final diary notebook. On the first page she wrote about herself: "The owner's maxim: Zest is what man needs!" A few months later, she and the other inhabitants of the annex celebrated the Allied invasion of France, which took place on June 6, 1944. They were certain the war would soon be over.

In one of her last diary entries, dated July 15, 1944, Anne wrote:

I simply can't build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery and death, I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever approaching thunder, which will destroy us too, I can feel the sufferings of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquility will return again. In the meantime, I must uphold my ideals, for perhaps the time will come when I shall be able to carry them out. yours, Anne M. Frank.

On August 4, 1944, Anne, her family, and the others in hiding were arrested by German and Dutch police officials. Her last entry was written on August 1, 1944.

The Diary Survives

The Franks and the four others hiding with them were discovered by the German SS and police on August 4, 1944. A German official and two Dutch police collaborators arrested the Franks the same day. They were soon sent to the Westerbork transit camp and then to concentration camps.

Anne's mother Edith Frank died in Auschwitz in January 1945. Anne and her sister Margot both died of typhus at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in February or March 1945. Their father, Otto, survived the war after Soviet forces liberated Auschwitz on January 27, 1945.

Otto Frank later described what it was like when the Nazis entered the annex in which he had been hiding. He said an SS man picked up a portfolio and asked whether there were any jewels in it. When Otto Frank said it only contained papers, the SS man threw the papers (and Anne Frank’s diary) on the floor, walking away with silverware and a candlestick in his briefcase. “If he had taken the diary with him,” Otto Frank recalled, “no one would ever have heard of my daughter.”

Miep Gies, one of the Dutch citizens who hid the Franks during the Holocaust, kept Anne Frank’s writings, including her diary. She handed the papers to Otto Frank on the day he learned of his daughters’ deaths. He organized the papers and worked doggedly to get the diary published, first in Dutch in 1947. The first American edition appeared in 1952.

The Diary of Anne Frank did not become a best-seller until after it was adapted for the stage, premiering in 1955 and winning a Pulitzer Prize the next year. The book remains immensely popular, having been translated into more than 70 languages and having sold more than 30 million copies.

There are three versions of the diary. The first is the diary as Anne originally wrote it from June 1942 to August 1944. Anne hoped to publish a book based on her entries, especially after a Dutch official announced in 1944 that he planned to collect eyewitness accounts of the German occupation. She then began editing her work, leaving out certain passages. That became the second version. Her father created a third version with his own edits as he sought to get the diary published after the war.

The third version is the most popularly known. Not all of the versions include Anne’s criticism of her mother or the references to her developing curiosity about sex -- the latter of which would have been especially controversial in 1947.

The home where the Franks hid in Amsterdam also continues to attract a large audience. Now known as the Anne Frank House, it drew more than 1.2 million visitors in 2017.

New Educational Resource

Diaries as Historical Sources Lesson

Students study examples of diaries written by young people during the Holocaust, particularly examining the ways in which Anne Frank, the most famous diarist of the Holocaust, thought about her audience while writing. By analyzing these diaries as sources, students are encouraged to think of themselves as historical actors and to consider how they are documenting their experiences for future historians.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Find diaries of other children impacted by the Holocaust. Compare and contrast their stories with Anne and Margot’s.

- Learn about the network of individuals who tried to shield the Franks from arrest. What pressures and motivations may have affected them?

- What can be learned from the choices of those who supported the Frank family in hiding?

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies, Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation, the Claims Conference, EVZ, and BMF for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

Essay on Anne Frank

Students are often asked to write an essay on Anne Frank in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Anne Frank

Introduction.

Anne Frank was a Jewish girl born on June 12, 1929, in Frankfurt, Germany. Her family moved to Amsterdam in 1933, escaping the growing Nazi power.

Life in Hiding

When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands in 1942, Anne and her family went into hiding in a secret annex. Here, she wrote her now-famous diary.

Anne’s diary, written between 1942 and 1944, provides a vivid account of her life in hiding. It’s a powerful testament to her courage and hope during a time of great fear and uncertainty.

After her death in a concentration camp in 1945, Anne’s father published her diary. Today, it serves as a reminder of the horrors of the Holocaust.

250 Words Essay on Anne Frank

Anne Frank, born Annelies Marie Frank on June 12, 1929, is one of the most renowned and most discussed Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Known for the diary she wrote while hiding from the Nazis in Amsterdam during World War II, her story is a powerful narrative of hope amidst the horrors of war.

Anne’s family went into hiding in a secret annex in her father’s office building in 1942, after her sister Margot received a call-up notice from the Central Office for Jewish Emigration. For over two years, Anne documented her experiences, thoughts, and emotions in her diary, providing a unique insight into the life of Jews during the Nazi regime.

In August 1944, the Secret Annex was discovered, and its occupants were sent to concentration camps. Anne and Margot died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen camp in early 1945. Her father, Otto Frank, the only survivor, returned to Amsterdam after the war and discovered Anne’s diary. Recognizing its historical and personal value, he published it in 1947.

Anne Frank’s Diary, now translated into more than 70 languages, serves as a stark reminder of the atrocities of the Holocaust. It also stands as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity. Anne’s poignant writing, her introspection, and her unwavering hope in humanity continue to inspire millions around the globe. Her story remains a powerful symbol against intolerance, racism, and prejudice.

500 Words Essay on Anne Frank

Anne frank: a voice from the shadows.

Anne Frank, a name that resonates with millions around the world, symbolizes the human spirit’s resilience in the face of horrifying adversity. Born on June 12, 1929, in Frankfurt, Germany, Annelies Marie Frank was a German-Dutch diarist, globally recognized for her poignant diary written during the Holocaust.

Early Life and Emigration

Anne Frank was born into a liberal Jewish family. Her father, Otto Frank, was a decorated German officer in World War I. However, when the Nazis came to power in 1933, Otto, sensing the impending danger, moved his family to Amsterdam, Netherlands. For a while, they lived a peaceful life, until the Nazis invaded the Netherlands in 1940, and the Franks found themselves entrapped once again.

The Secret Annex

In 1942, when the Nazis began deporting Jews to concentration camps, the Frank family went into hiding in a secret annex above Otto Frank’s office. Here, Anne began her diary, initially intended as a personal memoir but later revised with the aim of publication after the war. She documented her experiences, fears, hopes, and the claustrophobic reality of her life in hiding.

The Diary of Anne Frank

Anne’s diary, a unique blend of adolescent introspection and terrifying reality, is a testament to her extraordinary narrative skill. Her entries, filled with vivid descriptions and insightful reflections, depict the horrors of war, the human capacity for cruelty, and the sparks of kindness and humanity that persist even in the darkest times. She also explored her identity, ambitions, and the complex dynamics of growing up in such an oppressive environment.

Arrest and Death

In August 1944, the Frank family was betrayed, leading to their arrest and deportation. Anne and her sister Margot were transferred to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where they both died of typhus in March 1945, just weeks before the camp’s liberation. Anne was only 15.

After the war, Otto Frank, the only surviving member of the family, returned to Amsterdam, where he discovered Anne’s diary. He decided to fulfill her wish to have it published. The diary, translated into more than 70 languages, has become one of the world’s most widely read books, shedding light on the Holocaust’s horrors through the eyes of a young girl.

Anne Frank’s story is a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of prejudice and hatred. Her diary, a testament to the indomitable human spirit, continues to inspire generations, advocating for tolerance, empathy, and peace. Though her life was tragically cut short, her voice echoes through the corridors of history, urging us to remember and learn from the past.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Animal Testing

- Essay on Animal Farm

- Essay on Alternatives to Single-Use Plastic

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Thank you very much

thank you very much

Thank u very much this can help a lot 😇

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A suitable thesis statement for The Diary of a Young Girl could highlight its powerful testament against fascism, depicting an ordinary family trying to live a normal life under extreme...

The Diary of Anne Frank, which virtually all of us read as children, adolescents, or adults, is a radically altered, shortened, and skewed document. This, then, is a cautionary tale for our ...

In Dear Anne Frank: Poems (1994), she sees themselves connected through the reciprocal acts of reading and writing: ‘‘I name you and you are alive, Anne, although I died while reading you ...

Discuss the universal themes addressed in Anne Frank's diary, such as the importance of hope, the resilience of the human spirit, and the consequences of discrimination. Analyze how these themes continue to resonate with readers today. Examine the diary's role in Holocaust education and remembrance.

Is The Diary of Anne Frank a novel? How long did the Franks hide in the annex? Did Anne Frank survive? Where was the annex located? What does it mean when Anne writes that she feels “like a songbird whose wings have been ripped off and who keeps hurling itself against the bars of its dark cage”?

Outline for Anne Frank Essay. Categories: Anne Frank Holocaust. Words: 513 | Page: 1 | 3 min read. Published: Mar 5, 2024. Anne Frank, a young Jewish girl living in Amsterdam during the Holocaust, is known worldwide for her diary that chronicles her experiences hiding from the Nazis.

The Diary of Anne Frank is often the first exposure readers have to the history of the Holocaust. Learn about Anne's diary, including excerpts and images.

From a general summary to chapter summaries to explanations of famous quotes, the SparkNotes The Diary of Anne Frank Study Guide has everything you need to ace quizzes, tests, and essays.

Anne Frank, born Annelies Marie Frank on June 12, 1929, is one of the most renowned and most discussed Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Known for the diary she wrote while hiding from the Nazis in Amsterdam during World War II, her story is a powerful narrative of hope amidst the horrors of war.

Is The Diary of Anne Frank a novel? How long did the Franks hide in the annex? Did Anne Frank survive? Where was the annex located? What does it mean when Anne writes that she feels “like a songbird whose wings have been ripped off and who keeps hurling itself against the bars of its dark cage”?