- assignments basic law

Assignments: The Basic Law

The assignment of a right or obligation is a common contractual event under the law and the right to assign (or prohibition against assignments) is found in the majority of agreements, leases and business structural documents created in the United States.

As with many terms commonly used, people are familiar with the term but often are not aware or fully aware of what the terms entail. The concept of assignment of rights and obligations is one of those simple concepts with wide ranging ramifications in the contractual and business context and the law imposes severe restrictions on the validity and effect of assignment in many instances. Clear contractual provisions concerning assignments and rights should be in every document and structure created and this article will outline why such drafting is essential for the creation of appropriate and effective contracts and structures.

The reader should first read the article on Limited Liability Entities in the United States and Contracts since the information in those articles will be assumed in this article.

Basic Definitions and Concepts:

An assignment is the transfer of rights held by one party called the “assignor” to another party called the “assignee.” The legal nature of the assignment and the contractual terms of the agreement between the parties determines some additional rights and liabilities that accompany the assignment. The assignment of rights under a contract usually completely transfers the rights to the assignee to receive the benefits accruing under the contract. Ordinarily, the term assignment is limited to the transfer of rights that are intangible, like contractual rights and rights connected with property. Merchants Service Co. v. Small Claims Court , 35 Cal. 2d 109, 113-114 (Cal. 1950).

An assignment will generally be permitted under the law unless there is an express prohibition against assignment in the underlying contract or lease. Where assignments are permitted, the assignor need not consult the other party to the contract but may merely assign the rights at that time. However, an assignment cannot have any adverse effect on the duties of the other party to the contract, nor can it diminish the chance of the other party receiving complete performance. The assignor normally remains liable unless there is an agreement to the contrary by the other party to the contract.

The effect of a valid assignment is to remove privity between the assignor and the obligor and create privity between the obligor and the assignee. Privity is usually defined as a direct and immediate contractual relationship. See Merchants case above.

Further, for the assignment to be effective in most jurisdictions, it must occur in the present. One does not normally assign a future right; the assignment vests immediate rights and obligations.

No specific language is required to create an assignment so long as the assignor makes clear his/her intent to assign identified contractual rights to the assignee. Since expensive litigation can erupt from ambiguous or vague language, obtaining the correct verbiage is vital. An agreement must manifest the intent to transfer rights and can either be oral or in writing and the rights assigned must be certain.

Note that an assignment of an interest is the transfer of some identifiable property, claim, or right from the assignor to the assignee. The assignment operates to transfer to the assignee all of the rights, title, or interest of the assignor in the thing assigned. A transfer of all rights, title, and interests conveys everything that the assignor owned in the thing assigned and the assignee stands in the shoes of the assignor. Knott v. McDonald’s Corp ., 985 F. Supp. 1222 (N.D. Cal. 1997)

The parties must intend to effectuate an assignment at the time of the transfer, although no particular language or procedure is necessary. As long ago as the case of National Reserve Co. v. Metropolitan Trust Co ., 17 Cal. 2d 827 (Cal. 1941), the court held that in determining what rights or interests pass under an assignment, the intention of the parties as manifested in the instrument is controlling.

The intent of the parties to an assignment is a question of fact to be derived not only from the instrument executed by the parties but also from the surrounding circumstances. When there is no writing to evidence the intention to transfer some identifiable property, claim, or right, it is necessary to scrutinize the surrounding circumstances and parties’ acts to ascertain their intentions. Strosberg v. Brauvin Realty Servs., 295 Ill. App. 3d 17 (Ill. App. Ct. 1st Dist. 1998)

The general rule applicable to assignments of choses in action is that an assignment, unless there is a contract to the contrary, carries with it all securities held by the assignor as collateral to the claim and all rights incidental thereto and vests in the assignee the equitable title to such collateral securities and incidental rights. An unqualified assignment of a contract or chose in action, however, with no indication of the intent of the parties, vests in the assignee the assigned contract or chose and all rights and remedies incidental thereto.

More examples: In Strosberg v. Brauvin Realty Servs ., 295 Ill. App. 3d 17 (Ill. App. Ct. 1st Dist. 1998), the court held that the assignee of a party to a subordination agreement is entitled to the benefits and is subject to the burdens of the agreement. In Florida E. C. R. Co. v. Eno , 99 Fla. 887 (Fla. 1930), the court held that the mere assignment of all sums due in and of itself creates no different or other liability of the owner to the assignee than that which existed from the owner to the assignor.

And note that even though an assignment vests in the assignee all rights, remedies, and contingent benefits which are incidental to the thing assigned, those which are personal to the assignor and for his sole benefit are not assigned. Rasp v. Hidden Valley Lake, Inc ., 519 N.E.2d 153, 158 (Ind. Ct. App. 1988). Thus, if the underlying agreement provides that a service can only be provided to X, X cannot assign that right to Y.

Novation Compared to Assignment:

Although the difference between a novation and an assignment may appear narrow, it is an essential one. “Novation is a act whereby one party transfers all its obligations and benefits under a contract to a third party.” In a novation, a third party successfully substitutes the original party as a party to the contract. “When a contract is novated, the other contracting party must be left in the same position he was in prior to the novation being made.”

A sublease is the transfer when a tenant retains some right of reentry onto the leased premises. However, if the tenant transfers the entire leasehold estate, retaining no right of reentry or other reversionary interest, then the transfer is an assignment. The assignor is normally also removed from liability to the landlord only if the landlord consents or allowed that right in the lease. In a sublease, the original tenant is not released from the obligations of the original lease.

Equitable Assignments:

An equitable assignment is one in which one has a future interest and is not valid at law but valid in a court of equity. In National Bank of Republic v. United Sec. Life Ins. & Trust Co. , 17 App. D.C. 112 (D.C. Cir. 1900), the court held that to constitute an equitable assignment of a chose in action, the following has to occur generally: anything said written or done, in pursuance of an agreement and for valuable consideration, or in consideration of an antecedent debt, to place a chose in action or fund out of the control of the owner, and appropriate it to or in favor of another person, amounts to an equitable assignment. Thus, an agreement, between a debtor and a creditor, that the debt shall be paid out of a specific fund going to the debtor may operate as an equitable assignment.

In Egyptian Navigation Co. v. Baker Invs. Corp. , 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 30804 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 14, 2008), the court stated that an equitable assignment occurs under English law when an assignor, with an intent to transfer his/her right to a chose in action, informs the assignee about the right so transferred.

An executory agreement or a declaration of trust are also equitable assignments if unenforceable as assignments by a court of law but enforceable by a court of equity exercising sound discretion according to the circumstances of the case. Since California combines courts of equity and courts of law, the same court would hear arguments as to whether an equitable assignment had occurred. Quite often, such relief is granted to avoid fraud or unjust enrichment.

Note that obtaining an assignment through fraudulent means invalidates the assignment. Fraud destroys the validity of everything into which it enters. It vitiates the most solemn contracts, documents, and even judgments. Walker v. Rich , 79 Cal. App. 139 (Cal. App. 1926). If an assignment is made with the fraudulent intent to delay, hinder, and defraud creditors, then it is void as fraudulent in fact. See our article on Transfers to Defraud Creditors .

But note that the motives that prompted an assignor to make the transfer will be considered as immaterial and will constitute no defense to an action by the assignee, if an assignment is considered as valid in all other respects.

Enforceability of Assignments:

Whether a right under a contract is capable of being transferred is determined by the law of the place where the contract was entered into. The validity and effect of an assignment is determined by the law of the place of assignment. The validity of an assignment of a contractual right is governed by the law of the state with the most significant relationship to the assignment and the parties.

In some jurisdictions, the traditional conflict of laws rules governing assignments has been rejected and the law of the place having the most significant contacts with the assignment applies. In Downs v. American Mut. Liability Ins. Co ., 14 N.Y.2d 266 (N.Y. 1964), a wife and her husband separated and the wife obtained a judgment of separation from the husband in New York. The judgment required the husband to pay a certain yearly sum to the wife. The husband assigned 50 percent of his future salary, wages, and earnings to the wife. The agreement authorized the employer to make such payments to the wife.

After the husband moved from New York, the wife learned that he was employed by an employer in Massachusetts. She sent the proper notice and demanded payment under the agreement. The employer refused and the wife brought an action for enforcement. The court observed that Massachusetts did not prohibit assignment of the husband’s wages. Moreover, Massachusetts law was not controlling because New York had the most significant relationship with the assignment. Therefore, the court ruled in favor of the wife.

Therefore, the validity of an assignment is determined by looking to the law of the forum with the most significant relationship to the assignment itself. To determine the applicable law of assignments, the court must look to the law of the state which is most significantly related to the principal issue before it.

Assignment of Contractual Rights:

Generally, the law allows the assignment of a contractual right unless the substitution of rights would materially change the duty of the obligor, materially increase the burden or risk imposed on the obligor by the contract, materially impair the chance of obtaining return performance, or materially reduce the value of the performance to the obligor. Restat 2d of Contracts, § 317(2)(a). This presumes that the underlying agreement is silent on the right to assign.

If the contract specifically precludes assignment, the contractual right is not assignable. Whether a contract is assignable is a matter of contractual intent and one must look to the language used by the parties to discern that intent.

In the absence of an express provision to the contrary, the rights and duties under a bilateral executory contract that does not involve personal skill, trust, or confidence may be assigned without the consent of the other party. But note that an assignment is invalid if it would materially alter the other party’s duties and responsibilities. Once an assignment is effective, the assignee stands in the shoes of the assignor and assumes all of assignor’s rights. Hence, after a valid assignment, the assignor’s right to performance is extinguished, transferred to assignee, and the assignee possesses the same rights, benefits, and remedies assignor once possessed. Robert Lamb Hart Planners & Architects v. Evergreen, Ltd. , 787 F. Supp. 753 (S.D. Ohio 1992).

On the other hand, an assignee’s right against the obligor is subject to “all of the limitations of the assignor’s right, all defenses thereto, and all set-offs and counterclaims which would have been available against the assignor had there been no assignment, provided that these defenses and set-offs are based on facts existing at the time of the assignment.” See Robert Lamb , case, above.

The power of the contract to restrict assignment is broad. Usually, contractual provisions that restrict assignment of the contract without the consent of the obligor are valid and enforceable, even when there is statutory authorization for the assignment. The restriction of the power to assign is often ineffective unless the restriction is expressly and precisely stated. Anti-assignment clauses are effective only if they contain clear, unambiguous language of prohibition. Anti-assignment clauses protect only the obligor and do not affect the transaction between the assignee and assignor.

Usually, a prohibition against the assignment of a contract does not prevent an assignment of the right to receive payments due, unless circumstances indicate the contrary. Moreover, the contracting parties cannot, by a mere non-assignment provision, prevent the effectual alienation of the right to money which becomes due under the contract.

A contract provision prohibiting or restricting an assignment may be waived, or a party may so act as to be estopped from objecting to the assignment, such as by effectively ratifying the assignment. The power to void an assignment made in violation of an anti-assignment clause may be waived either before or after the assignment. See our article on Contracts.

Noncompete Clauses and Assignments:

Of critical import to most buyers of businesses is the ability to ensure that key employees of the business being purchased cannot start a competing company. Some states strictly limit such clauses, some do allow them. California does restrict noncompete clauses, only allowing them under certain circumstances. A common question in those states that do allow them is whether such rights can be assigned to a new party, such as the buyer of the buyer.

A covenant not to compete, also called a non-competitive clause, is a formal agreement prohibiting one party from performing similar work or business within a designated area for a specified amount of time. This type of clause is generally included in contracts between employer and employee and contracts between buyer and seller of a business.

Many workers sign a covenant not to compete as part of the paperwork required for employment. It may be a separate document similar to a non-disclosure agreement, or buried within a number of other clauses in a contract. A covenant not to compete is generally legal and enforceable, although there are some exceptions and restrictions.

Whenever a company recruits skilled employees, it invests a significant amount of time and training. For example, it often takes years before a research chemist or a design engineer develops a workable knowledge of a company’s product line, including trade secrets and highly sensitive information. Once an employee gains this knowledge and experience, however, all sorts of things can happen. The employee could work for the company until retirement, accept a better offer from a competing company or start up his or her own business.

A covenant not to compete may cover a number of potential issues between employers and former employees. Many companies spend years developing a local base of customers or clients. It is important that this customer base not fall into the hands of local competitors. When an employee signs a covenant not to compete, he or she usually agrees not to use insider knowledge of the company’s customer base to disadvantage the company. The covenant not to compete often defines a broad geographical area considered off-limits to former employees, possibly tens or hundreds of miles.

Another area of concern covered by a covenant not to compete is a potential ‘brain drain’. Some high-level former employees may seek to recruit others from the same company to create new competition. Retention of employees, especially those with unique skills or proprietary knowledge, is vital for most companies, so a covenant not to compete may spell out definite restrictions on the hiring or recruiting of employees.

A covenant not to compete may also define a specific amount of time before a former employee can seek employment in a similar field. Many companies offer a substantial severance package to make sure former employees are financially solvent until the terms of the covenant not to compete have been met.

Because the use of a covenant not to compete can be controversial, a handful of states, including California, have largely banned this type of contractual language. The legal enforcement of these agreements falls on individual states, and many have sided with the employee during arbitration or litigation. A covenant not to compete must be reasonable and specific, with defined time periods and coverage areas. If the agreement gives the company too much power over former employees or is ambiguous, state courts may declare it to be overbroad and therefore unenforceable. In such case, the employee would be free to pursue any employment opportunity, including working for a direct competitor or starting up a new company of his or her own.

It has been held that an employee’s covenant not to compete is assignable where one business is transferred to another, that a merger does not constitute an assignment of a covenant not to compete, and that a covenant not to compete is enforceable by a successor to the employer where the assignment does not create an added burden of employment or other disadvantage to the employee. However, in some states such as Hawaii, it has also been held that a covenant not to compete is not assignable and under various statutes for various reasons that such covenants are not enforceable against an employee by a successor to the employer. Hawaii v. Gannett Pac. Corp. , 99 F. Supp. 2d 1241 (D. Haw. 1999)

It is vital to obtain the relevant law of the applicable state before drafting or attempting to enforce assignment rights in this particular area.

Conclusion:

In the current business world of fast changing structures, agreements, employees and projects, the ability to assign rights and obligations is essential to allow flexibility and adjustment to new situations. Conversely, the ability to hold a contracting party into the deal may be essential for the future of a party. Thus, the law of assignments and the restriction on same is a critical aspect of every agreement and every structure. This basic provision is often glanced at by the contracting parties, or scribbled into the deal at the last minute but can easily become the most vital part of the transaction.

As an example, one client of ours came into the office outraged that his co venturer on a sizable exporting agreement, who had excellent connections in Brazil, had elected to pursue another venture instead and assigned the agreement to a party unknown to our client and without the business contacts our client considered vital. When we examined the handwritten agreement our client had drafted in a restaurant in Sao Paolo, we discovered there was no restriction on assignment whatsoever…our client had not even considered that right when drafting the agreement after a full day of work.

One choses who one does business with carefully…to ensure that one’s choice remains the party on the other side of the contract, one must master the ability to negotiate proper assignment provisions.

Founded in 1939, our law firm combines the ability to represent clients in domestic or international matters with the personal interaction with clients that is traditional to a long established law firm.

Read more about our firm

© 2024, Stimmel, Stimmel & Roeser, All rights reserved | Terms of Use | Site by Bay Design

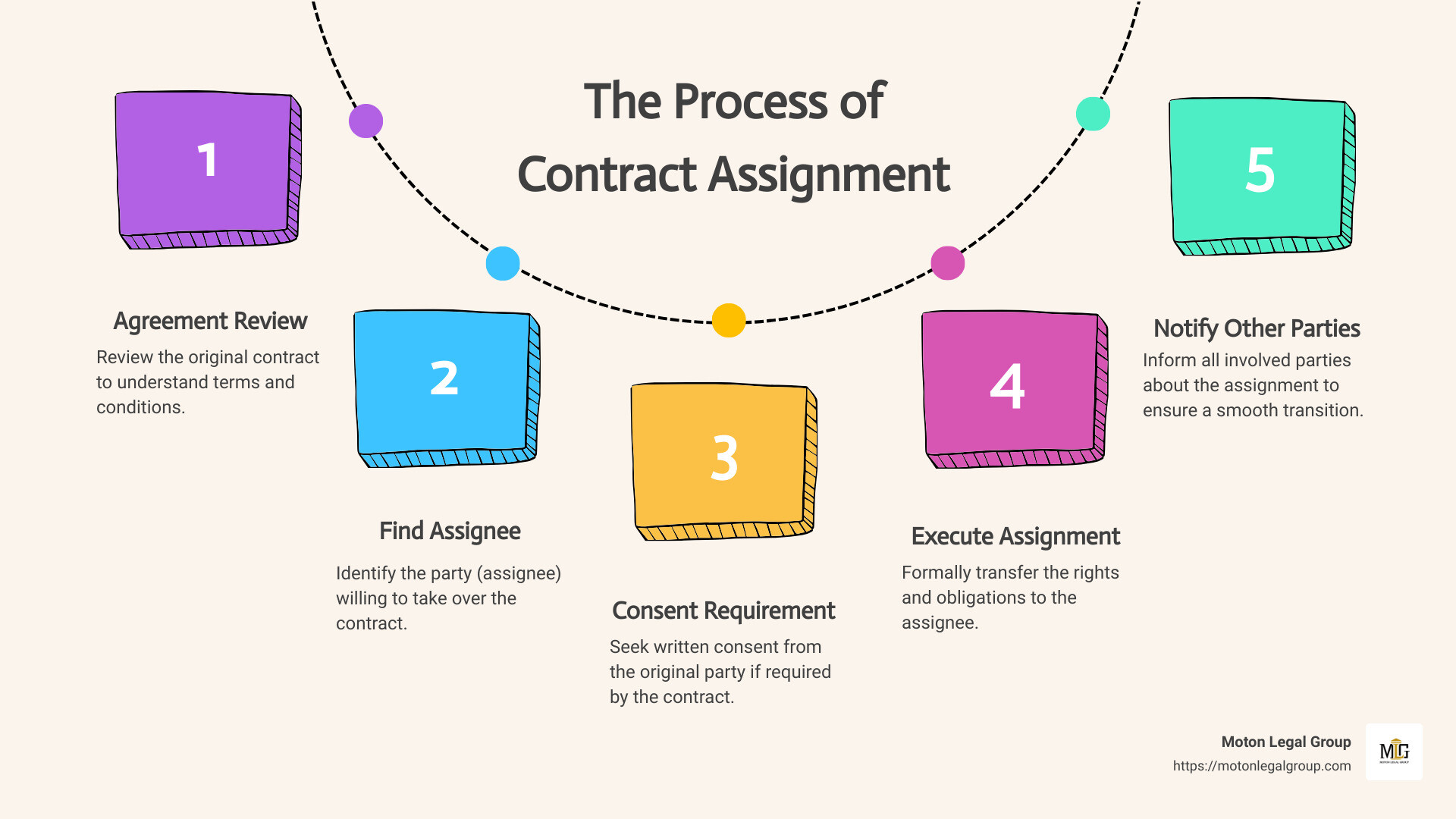

Assignment of Contract

Jump to section, what is an assignment of contract.

An assignment of contract is a legal term that describes the process that occurs when the original party (assignor) transfers their rights and obligations under their contract to a third party (assignee). When an assignment of contract happens, the original party is relieved of their contractual duties, and their role is replaced by the approved incoming party.

How Does Assignment of Contract Work?

An assignment of contract is simpler than you might think.

The process starts with an existing contract party who wishes to transfer their contractual obligations to a new party.

When this occurs, the existing contract party must first confirm that an assignment of contract is permissible under the legally binding agreement . Some contracts prohibit assignments of contract altogether, and some require the other parties of the agreement to agree to the transfer. However, the general rule is that contracts are freely assignable unless there is an explicit provision that says otherwise.

In other cases, some contracts allow an assignment of contract without any formal notification to other contract parties. If this is the case, once the existing contract party decides to reassign his duties, he must create a “Letter of Assignment ” to notify any other contract signers of the change.

The Letter of Assignment must include details about who is to take over the contractual obligations of the exiting party and when the transfer will take place. If the assignment is valid, the assignor is not required to obtain the consent or signature of the other parties to the original contract for the valid assignment to take place.

Check out this article to learn more about how assigning a contract works.

Contract Assignment Examples

Contract assignments are great tools for contract parties to use when they wish to transfer their commitments to a third party. Here are some examples of contract assignments to help you better understand them:

Anna signs a contract with a local trash company that entitles her to have her trash picked up twice a week. A year later, the trash company transferred her contract to a new trash service provider. This contract assignment effectively makes Anna’s contract now with the new service provider.

Hasina enters a contract with a national phone company for cell phone service. The company goes into bankruptcy and needs to close its doors but decides to transfer all current contracts to another provider who agrees to honor the same rates and level of service. The contract assignment is completed, and Hasina now has a contract with the new phone company as a result.

Here is an article where you can find out more about contract assignments.

Jeremiah C.

Assignment of contract in real estate.

Assignment of contract is also used in real estate to make money without going the well-known routes of buying and flipping houses. When real estate LLC investors use an assignment of contract, they can make money off properties without ever actually buying them by instead opting to transfer real estate contracts .

This process is called real estate wholesaling.

Real Estate Wholesaling

Real estate wholesaling consists of locating deals on houses that you don’t plan to buy but instead plan to enter a contract to reassign the house to another buyer and pocket the profit.

The process is simple: real estate wholesalers negotiate purchase contracts with sellers. Then, they present these contracts to buyers who pay them an assignment fee for transferring the contract.

This process works because a real estate purchase agreement does not come with the obligation to buy a property. Instead, it sets forth certain purchasing parameters that must be fulfilled by the buyer of the property. In a nutshell, whoever signs the purchase contract has the right to buy the property, but those rights can usually be transferred by means of an assignment of contract.

This means that as long as the buyer who’s involved in the assignment of contract agrees with the purchasing terms, they can legally take over the contract.

But how do real estate wholesalers find these properties?

It is easier than you might think. Here are a few examples of ways that wholesalers find cheap houses to turn a profit on:

- Direct mailers

- Place newspaper ads

- Make posts in online forums

- Social media posts

The key to finding the perfect home for an assignment of contract is to locate sellers that are looking to get rid of their properties quickly. This might be a family who is looking to relocate for a job opportunity or someone who needs to make repairs on a home but can’t afford it. Either way, the quicker the wholesaler can close the deal, the better.

Once a property is located, wholesalers immediately go to work getting the details ironed out about how the sale will work. Transparency is key when it comes to wholesaling. This means that when a wholesaler intends to use an assignment of contract to transfer the rights to another person, they are always upfront about during the preliminary phases of the sale.

In addition to this practice just being good business, it makes sure the process goes as smoothly as possible later down the line. Wholesalers are clear in their intent and make sure buyers know that the contract could be transferred to another buyer before the closing date arrives.

After their offer is accepted and warranties are determined, wholesalers move to complete a title search . Title searches ensure that sellers have the right to enter into a purchase agreement on the property. They do this by searching for any outstanding tax payments, liens , or other roadblocks that could prevent the sale from going through.

Wholesalers also often work with experienced real estate lawyers who ensure that all of the legal paperwork is forthcoming and will stand up in court. Lawyers can also assist in the contract negotiation process if needed but often don’t come in until the final stages.

If the title search comes back clear and the real estate lawyer gives the green light, the wholesaler will immediately move to locate an entity to transfer the rights to buy.

One of the most attractive advantages of real estate wholesaling is that very little money is needed to get started. The process of finding a seller, negotiating a price, and performing a title search is an extremely cheap process that almost anyone can do.

On the other hand, it is not always a positive experience. It can be hard for wholesalers to find sellers who will agree to sell their homes for less than the market value. Even when they do, there is always a chance that the transferred buyer will back out of the sale, which leaves wholesalers obligated to either purchase the property themselves or scramble to find a new person to complete an assignment of contract with.

Learn more about assignment of contract in real estate by checking out this article .

Who Handles Assignment of Contract?

The best person to handle an assignment of contract is an attorney. Since these are detailed legal documents that deal with thousands of dollars, it is never a bad idea to have a professional on your side. If you need help with an assignment of contract or signing a business contract , post a project on ContractsCounsel. There, you can connect with attorneys who know everything there is to know about assignment of contract amendment and can walk you through the whole process.

Meet some of our Lawyers

Shelia A. Huggins is a 20-year North Carolina licensed attorney, focusing primarily on business, contracts, arts and entertainment, social media, and internet law. She previously served on the Board of Visitors for the North Carolina Central University School of Business and the Board of Advisors for the Alamance Community College Small Business Center. Ms. Huggins has taught Business and Entertainment Law at North Carolina Central University’s law school and lectured on topics such as business formation, partnerships, independent contractor agreements, social media law, and employment law at workshops across the state. You can learn more about me here: www.sheliahugginslaw.com www.instagram.com/mslegalista www.youtube.com/mslegalista www.facebook.com/sheliahuugginslaw

Steven Stark has more than 35 years of experience in business and commercial law representing start-ups as well as large and small companies spanning a wide variety of industries. Steven has provided winning strategies, valuable advice, and highly effective counsel on legal issues in the areas of Business Entity Formation and Organization, Drafting Key Business Contracts, Trademark and Copyright Registration, Independent Contractor Relationships, and Website Compliance, including Terms and Privacy Policies. Steven has also served as General Counsel for companies providing software development, financial services, digital marketing, and eCommerce platforms. Steven’s tactical business and client focused approach to drafting contracts, polices and corporate documents results in favorable outcomes at a fraction of the typical legal cost to his clients. Steven received his Juris Doctor degree at New York Law School and his Bachelor of Business Administration degree at Hofstra University.

Rhea de Aenlle is a business-savvy attorney with extensive experience in Privacy & Data Security (CIPP/US, CIPP/E), GDPR, CCPA, HIPAA, FERPA, Intellectual Property, and Commercial Contracts. She has over 25 years of legal experience as an in-house counsel, AM Law 100 firm associate, and a solo practice attorney. Rhea works with start-up and midsize technology companies.

Bukhari Nuriddin is the Owner of The Nuriddin Law Company, P.C., in Atlanta, Georgia and an “Of Counsel” attorney with The Baig Firm specializing in Transactional Law and Wills, Trusts and Estates. He is an attorney at law and general counsel with extensive experience providing creative, elegant and practical solutions to the legal and policy challenges faced by entrepreneurs, family offices, and municipalities. During his legal careers he has worked with entrepreneurs from a wide array of industries to help them establish and grow their businesses and effectuate their transactional goals. He has helped establish family offices with millions of dollars in assets under management structure their estate plans and philanthropic endeavors. He recently completed a large disparity study for the City of Birmingham, Alabama that was designed to determine whether minority and women-owned businesses have an equal opportunity to participate in city contracting opportunities. He is a trusted advisor with significant knowledge and technical experience for structuring and finalizing a wide variety of complex commercial transactions, estate planning matters and public policy initiatives. Raised in Providence, Rhode Island, Bukhari graduated from Classical High School and attended Morehouse College and Howard University School of Law. Bukhari has two children with his wife, Tiffany, and they live in the Vinings area of Smyrna.

John has extensive leadership experience in various industries, including hospitality and event-based businesses, then co-founded a successful event bar company in 2016. As co-founder, John routinely negotiated agreements with venues, suppliers, and other external partners, swiftly reaching agreement while protecting the brand and strategic objectives of the company. He leverages his business experience to provide clients with strategic legal counsel and negotiates attractive terms.

Patent attorney with master's in electrical engineering and biglaw experience.

Benjamin S.

Benjamin Snipes (JD/MBA/LLM) has 20 years of experience advising clients and drafting contracts in business and commercial matters.

Find the best lawyer for your project

Need help with a contract agreement.

Post Your Project

Get Free Bids to Compare

Hire Your Lawyer

CONTRACT LAWYERS BY TOP CITIES

- Austin Contracts Lawyers

- Boston Contracts Lawyers

- Chicago Contracts Lawyers

- Dallas Contracts Lawyers

- Denver Contracts Lawyers

- Houston Contracts Lawyers

- Los Angeles Contracts Lawyers

- New York Contracts Lawyers

- Phoenix Contracts Lawyers

- San Diego Contracts Lawyers

- Tampa Contracts Lawyers

ASSIGNMENT OF CONTRACT LAWYERS BY CITY

- Austin Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- Boston Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- Chicago Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- Dallas Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- Denver Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- Houston Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- Los Angeles Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- New York Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- Phoenix Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- San Diego Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

- Tampa Assignment Of Contract Lawyers

Learn About Contracts

- Novation Contract

other helpful articles

- How much does it cost to draft a contract?

- Do Contract Lawyers Use Templates?

- How do Contract Lawyers charge?

- Business Contract Lawyers: How Can They Help?

- What to look for when hiring a lawyer

Quick, user friendly and one of the better ways I've come across to get ahold of lawyers willing to take new clients.

Contracts Counsel was incredibly helpful and easy to use. I submitted a project for a lawyer's help within a day I had received over 6 proposals from qualified lawyers. I submitted a bid that works best for my business and we went forward with the project.

I never knew how difficult it was to obtain representation or a lawyer, and ContractsCounsel was EXACTLY the type of service I was hoping for when I was in a pinch. Working with their service was efficient, effective and made me feel in control. Thank you so much and should I ever need attorney services down the road, I'll certainly be a repeat customer.

I got 5 bids within 24h of posting my project. I choose the person who provided the most detailed and relevant intro letter, highlighting their experience relevant to my project. I am very satisfied with the outcome and quality of the two agreements that were produced, they actually far exceed my expectations.

How It Works

Want to speak to someone.

Get in touch below and we will schedule a time to connect!

Find lawyers and attorneys by city

(404) 738-5471

Ultimate Checklist for Understanding Contract Assignment Rules

- February 28, 2024

- Moton Legal Group

In contracts, understanding assignment is key. Simply put, an assignment in contract law is when one party (the assignor) transfers their rights and responsibilities under a contract to another party (the assignee). This can include anything from leasing agreements to business operations. But why is this important? It’s because it allows for flexibility in business and personal dealings, a critical component in our world.

Here’s a quick rundown: – Contract Basics: The foundational agreements between parties. – Assignment Importance: Allowing the transfer of obligations and benefits to keep up with life’s changes.

Contracts are a staple in both personal and business worlds, acting as the backbone to many transactions and agreements encountered daily. Understanding the nuances, like assignments, can empower you to navigate these waters with confidence and ease. Whether you’re a business owner in the Southeast looking to expand or an individual managing personal agreements, grasp these basics, and you’re on the right path.

Understanding Contract Assignment

Contract Assignment sounds complicated, right? But, let’s break it down into simple terms. In contracts and legal agreements, knowing about assignment can save you a lot of headaches down the road. Whether you’re a business owner, a landlord, or just someone who deals with contracts, this is for you.

Legal Definition

At its core, contract assignment is about transferring rights or obligations under a contract from one party to another. Think of it as passing a baton in a relay race. The original party (the assignor) hands off their responsibilities or benefits to someone else (the assignee). But, there’s a twist – the race keeps going with the new runner without starting over.

Contract Law

In contract law, assignment comes into play in various ways. For example, if you’re a freelancer and you’ve agreed to complete a project but suddenly find yourself overbooked, you might assign that contract to another freelancer. This way, the job gets done, and your client is happy. However, not all contracts can be freely assigned. Some require the other party’s consent, and others can’t be assigned at all, especially if they involve personal skills or confidential trust.

Property Law

When it comes to property law, assignment often surfaces in landlord-tenant relationships. Say you’re renting a shop for your business, but you decide to move. If your lease allows it, you might assign your lease to another business. This means they take over your lease, stepping into your shoes, with all the rights and obligations that come with it.

The concept might seem straightforward, but there are important legal requirements and potential pitfalls to be aware of. For instance, an assignment could be prohibited by the contract itself, or it may significantly change the original deal’s terms in a way that’s not allowed. Plus, when you’re dealing with something that requires a unique skill set, like an artist or a consultant, those services typically can’t be passed on to someone else without agreement from all parties involved.

To navigate these complexities, understanding the fundamentals of assignment in contract law and property law is crucial. It ensures that when you’re ready to pass that baton, you’re doing it in a way that’s legal, effective, and doesn’t leave you tripping up before you reach the finish line.

The goal here is to make sure everyone involved understands what’s happening and agrees to it. That way, assignments can be a useful tool to manage your contracts and property agreements, keeping things moving smoothly even when changes come up.

For more detailed exploration on this topic, consider checking the comprehensive guide on Assignment (law)). This resource dives deeper into the nuances of contract assignment, offering insights and examples that can help clarify this complex area of law.

By grasping these basics, you’re well on your way to mastering the art of contract assignment. Whether you’re dealing with leases, business deals, or any agreement in between, knowing how to effectively assign a contract can be a game-changer.

Key Differences Between Assignment and Novation

When diving into contracts, two terms that often cause confusion are assignment and novation . While both deal with transferring obligations and rights under a contract, they are fundamentally different in several key aspects. Understanding these differences is crucial for anyone involved in contract management or negotiation.

Rights Transfer

Assignment involves the transfer of benefits or rights from one party (the assignor) to another (the assignee). However, it’s important to note that only the benefits of the contract can be assigned, not the burdens. For instance, if someone has the right to receive payments under a contract, they can assign this right to someone else.

Novation , on the other hand, is more comprehensive. It involves transferring both the rights and obligations under a contract from one party to a new party. With novation, the original party is completely released from the contract, and a new contractual relationship is formed between the remaining and the new party. This is a key distinction because, in novation, all parties must agree to this new arrangement.

Obligations Transfer

Assignment doesn’t transfer the original party’s obligations under the contract. The assignor (the original party who had the rights under the contract) might still be liable if the assignee fails to fulfill the contract terms.

In contrast, novation transfers all obligations to the new party. Once a novation is complete, the new party takes over all rights and obligations, leaving the original party with no further legal liabilities or rights under the contract.

Written Agreement

While assignments can sometimes be informal or even verbal, novation almost always requires a written agreement. This is because novation affects more parties’ rights and obligations and has a more significant impact on the contractual relationship. A written agreement ensures that all parties are clear about the terms of the novation and their respective responsibilities.

In practice, the need for a written agreement in novation serves as a protection for all parties involved. It ensures that the transfer of obligations is clearly documented and legally enforceable.

For example, let’s say Alex agrees to paint Bailey’s house for $1,000. Later, Alex decides they can’t complete the job and wants Chris to take over. If Bailey agrees, they can sign a novation agreement where Chris agrees to paint the house under the same conditions. Alex is then relieved from the original contract, and Chris becomes responsible for completing the painting job.

Understanding the difference between assignment and novation is critical for anyone dealing with contracts. While both processes allow for the transfer of rights or obligations, they do so in different ways and with varying implications for all parties involved. Knowing when and how to use each can help ensure that your contractual relationships are managed effectively and legally sound.

For further in-depth information and real-life case examples on assignment in contract law, you can explore detailed resources such as Assignment (law) on Wikipedia).

Next, we’ll delve into the legal requirements for a valid assignment, touching on express prohibition, material change, future rights, and the rare skill requirement. Understanding these will further equip you to navigate the complexities of contract assignments successfully.

Legal Requirements for a Valid Assignment

When dealing with assignment in contract law , it’s crucial to understand the legal backbone that supports a valid assignment. This ensures that the assignment stands up in a court of law if disputes arise. Let’s break down the must-know legal requirements: express prohibition, material change, future rights, and rare skill requirement.

Express Prohibition

The first stop on our checklist is to look for an express prohibition against assignment in the contract. This is a clause that outright states assignments are not allowed without the other party’s consent. If such language exists and you proceed with an assignment, you could be breaching the contract. Always read the fine print or have a legal expert review the contract for you.

Material Change

Next up is the material change requirement. The law states that an assignment cannot significantly alter the duties, increase the burdens, or impair the chances of the other party receiving due performance under the contract. For instance, if the contract involves personal services tailored to the specific party, assigning it to someone else might change the expected outcome, making such an assignment invalid.

Future Rights

Another important aspect is future rights . The rule here is straightforward: you can’t assign what you don’t have. This means that a promise to assign rights you may acquire in the future is generally not enforceable at present. An effective assignment requires that the rights exist at the time of the assignment.

Rare Skill Requirement

Lastly, let’s talk about the rare skill requirement . Some contracts are so specialized that they cannot be assigned to another party without compromising the contract’s integrity. This is often the case with contracts that rely on an individual’s unique skills or trust. Think of an artist commissioned for a portrait or a lawyer hired for their specialized legal expertise. In these scenarios, assignments are not feasible as they could severely impact the contract’s intended outcome.

Understanding these legal requirements is pivotal for navigating the complexities of assignment in contract law. By ensuring compliance with these principles, you can effectively manage contract assignments, safeguarding your interests and those of the other contracting party.

For anyone looking to delve deeper into the intricacies of contract law, you can explore detailed resources such as Assignment (law) on Wikipedia).

Moving forward, we’ll explore the common types of contract assignments, from landlord-tenant agreements to business contracts and intellectual property transfers. This will give you a clearer picture of how assignments work across different legal landscapes.

Common Types of Contract Assignments

When we dive into assignment in contract law , we find it touches nearly every aspect of our business and personal lives. Let’s simplify this complex topic by looking at some of the most common types of contract assignments you might encounter.

Landlord-Tenant Agreements

Imagine you’re renting a fantastic apartment but have to move because of a new job. Instead of breaking your lease, you can assign your lease to someone else. This means the new tenant takes over your lease, including rent payments and maintenance responsibilities. However, it’s crucial that the landlord agrees to this switch. If done right, it’s a win-win for everyone involved.

Business Contracts

In the business world, contract assignments are a daily occurrence. For example, if a company agrees to provide services but then realizes it’s overbooked, it can assign the contract to another company that can fulfill the obligations. This way, the project is completed on time, and the client remains happy. It’s a common practice that ensures flexibility and efficiency in business operations.

Intellectual Property

Intellectual property (IP) assignments are fascinating and complex. If an inventor creates a new product, they can assign their patent rights to a company in exchange for a lump sum or royalties. This transfer allows the company to produce and sell the invention, while the inventor benefits financially. However, it’s critical to note that with trademarks, the goodwill associated with the mark must also be transferred to maintain its value.

Understanding these types of assignments helps clarify the vast landscape of contract law. Whether it’s a cozy apartment, a crucial business deal, or a groundbreaking invention, assignments play a pivotal role in ensuring these transitions happen smoothly.

As we navigate through the realm of contract assignments, each type has its own set of rules and best practices. The key is to ensure all parties are on the same page and that the assignment is executed properly to avoid any legal pitfalls.

Diving deeper into the subject, next, we will explore how to execute a contract assignment effectively, ensuring all legal requirements are met and the process runs as smoothly as possible.

How to Execute a Contract Assignment Effectively

Executing a contract assignment effectively is crucial to ensure that all legal requirements are met and the process runs smoothly. Here’s a straightforward guide to help you navigate this process without any hiccups.

Written Consent

First and foremost, get written consent . This might seem like a no-brainer, but it’s surprising how often this step is overlooked. If the original contract requires the consent of the other party for an assignment to be valid, make sure you have this in black and white. Not just a handshake or a verbal agreement. This ensures clarity and avoids any ambiguity or disputes down the line.

Notice of Assignment

Next up, provide a notice of assignment to all relevant parties. This is not just common courtesy; it’s often a legal requirement. It informs all parties involved about the change in the assignment of rights or obligations under the contract. Think of it as updating your address with the post office; everyone needs to know where to send the mail now.

Privity of Estate

Understanding privity of estate is key in real estate transactions and leases. It refers to the legal relationship that exists between parties under a contract. When you assign a contract, the assignee steps into your shoes, but the original terms of the contract still apply. This means the assignee needs to be aware of and comply with the original agreement’s requirements.

Secondary Liability

Lastly, let’s talk about secondary liability . Just because you’ve assigned a contract doesn’t always mean you’re off the hook. In some cases, the original party (the assignor) may still hold some liability if the assignee fails to perform under the contract. It’s essential to understand the terms of your assignment agreement and whether it includes a release from liability for the assignor.

Executing a contract assignment effectively is all about dotting the I’s and crossing the T’s . By following these steps—securing written consent, issuing a notice of assignment, understanding privity of estate, and clarifying secondary liability—you’re setting yourself up for a seamless transition.

The goal is to ensure all parties are fully informed and agreeable to the changes being made. This not only helps in maintaining good relationships but also in avoiding potential legal issues down the line.

We’ll dive into some of the frequently asked questions about contract assignment to clear any lingering doubts.

Frequently Asked Questions about Contract Assignment

When navigating contracts, questions often arise, particularly about the concepts of assignment and novation. Let’s break these down into simpler terms.

What does assignment of a contract mean?

In the realm of assignment in contract law , think of assignment as passing the baton in a relay race. It’s where one party (the assignor) transfers their rights and benefits under a contract to another party (the assignee). However, unlike a relay race, the original party might still be on the hook for obligations unless the contract says otherwise. It’s like handing off the baton but still running alongside the new runner just in case.

Is an assignment legally binding?

Absolutely, an assignment is as binding as a pinky promise in the playground – but with legal muscle behind it. Once an assignment meets the necessary legal criteria (like not significantly changing the obligor’s duties or having express consent if required), it’s set in stone. This means both the assignee and the assignor must honor this transfer of rights or face potential legal actions. It’s a serious commitment, not just a casual exchange.

What is the difference between assignment and novation?

Now, this is where it gets a bit more intricate. If assignment is passing the baton, novation is forming a new team mid-race. It involves replacing an old obligation with a new one or adding a new party to take over an old one’s duties. Crucially, novation extinguishes the old contract and requires all original and new parties to agree. It’s a clean slate – the original party walks away, and the new party steps in, no strings attached.

While both assignment and novation change the playing field of a contract, novation requires a unanimous thumbs up from everyone involved, completely freeing the original party from their obligations. On the other hand, an assignment might leave the original party watching from the sidelines, ready to jump back in if needed.

Understanding these facets of assignment in contract law is crucial, whether you’re diving into a new agreement or navigating an existing one. Knowledge is power – especially when it comes to contracts.

As we wrap up these FAQs, the legal world of contracts is vast and sometimes complex, but breaking it down into bite-sized pieces can help demystify the process and empower you in your legal undertakings.

Here’s a helpful resource for further reading on the difference between assignment and cession.

Now, let’s continue on to the conclusion to tie all these insights together.

Navigating assignment in contract law can seem like a daunting task at first glance. However, with the right information and guidance, it becomes an invaluable tool in ensuring that your rights and obligations are protected and effectively managed in any contractual relationship.

At Moton Legal Group, we understand the intricacies of contract law and are dedicated to providing you with the expertise and support you need to navigate these waters. Whether you’re dealing with a straightforward contract assignment or facing more complex legal challenges, our team is here to help. We pride ourselves on our ability to demystify legal processes and make them accessible to everyone.

The key to successfully managing any contract assignment lies in understanding your rights, the obligations involved, and the potential impacts on all parties. It’s about ensuring that the assignment is executed in a way that is legally sound and aligns with your interests.

If you’re in need of assistance with a contract review, looking to understand more about how contract assignments work, or simply seeking legal advice on your contractual rights and responsibilities, Moton Legal Group is here for you. Our team of experienced attorneys is committed to providing the clarity, insight, and support you need to navigate the complexities of contract law with confidence.

For more information on how we can assist you with your contract review and other legal needs, visit our contract review service page .

In the constantly evolving landscape of contract law, having a trusted legal partner can make all the difference. Let Moton Legal Group be your guide, ensuring that your contractual dealings are handled with the utmost care, professionalism, and expertise. Together, we can navigate the complexities of contract law and secure the best possible outcomes for your legal matters.

Thank you for joining us on this journey through the fundamentals of assignment in contract law. We hope you found this information helpful and feel more empowered to handle your contractual affairs with confidence.

For more information Call :

Reach out now.

" * " indicates required fields

Recent Blog Posts:

The Ultimate Guide to Elements of Contract Law: Understanding the Basics

A Comprehensive Guide to Business Sales and Purchase Agreements

Everything You Need to Know About Contract Types

A Comprehensive Guide to Business Purchase Agreements PDF

The Complete Guide to Understanding Contract Law Examples

How to Get Your Business Purchase Agreement Form Template Now

14.1 Assignment of Contract Rights

Learning objectives.

- Understand what an assignment is and how it is made.

- Recognize the effect of the assignment.

- Know when assignments are not allowed.

- Understand the concept of assignor’s warranties.

The Concept of a Contract Assignment

Contracts create rights and duties. By an assignment The passing or delivering by one person to another of the right to a contract benefit. , an obligee One to whom an obligation is owed. (one who has the right to receive a contract benefit) transfers a right to receive a contract benefit owed by the obligor One who owes an obligation. (the one who has a duty to perform) to a third person ( assignee One to whom the right to receive benefit of a contract is passed or delivered. ); the obligee then becomes an assignor One who agrees to allow another to receive the benefit of a contract. (one who makes an assignment).

The Restatement (Second) of Contracts defines an assignment of a right as “a manifestation of the assignor’s intention to transfer it by virtue of which the assignor’s right to performance by the obligor is extinguished in whole or in part and the assignee acquires the right to such performance.” Restatement (Second) of Contracts, Section 317(1). The one who makes the assignment is both an obligee and a transferor. The assignee acquires the right to receive the contractual obligations of the promisor, who is referred to as the obligor (see Figure 14.1 "Assignment of Rights" ). The assignor may assign any right unless (1) doing so would materially change the obligation of the obligor, materially burden him, increase his risk, or otherwise diminish the value to him of the original contract; (2) statute or public policy forbids the assignment; or (3) the contract itself precludes assignment. The common law of contracts and Articles 2 and 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) govern assignments. Assignments are an important part of business financing, such as factoring. A factor A person who pays money to receive another’s executory contractual benefits. is one who purchases the right to receive income from another.

Figure 14.1 Assignment of Rights

Method of Assignment

Manifesting assent.

To effect an assignment, the assignor must make known his intention to transfer the rights to the third person. The assignor’s intention must be that the assignment is effective without need of any further action or any further manifestation of intention to make the assignment. In other words, the assignor must intend and understand himself to be making the assignment then and there; he is not promising to make the assignment sometime in the future.

Under the UCC, any assignments of rights in excess of $5,000 must be in writing, but otherwise, assignments can be oral and consideration is not required: the assignor could assign the right to the assignee for nothing (not likely in commercial transactions, of course). Mrs. Franklin has the right to receive $750 a month from the sale of a house she formerly owned; she assigns the right to receive the money to her son Jason, as a gift. The assignment is good, though such a gratuitous assignment is usually revocable, which is not the case where consideration has been paid for an assignment.

Acceptance and Revocation

For the assignment to become effective, the assignee must manifest his acceptance under most circumstances. This is done automatically when, as is usually the case, the assignee has given consideration for the assignment (i.e., there is a contract between the assignor and the assignee in which the assignment is the assignor’s consideration), and then the assignment is not revocable without the assignee’s consent. Problems of acceptance normally arise only when the assignor intends the assignment as a gift. Then, for the assignment to be irrevocable, either the assignee must manifest his acceptance or the assignor must notify the assignee in writing of the assignment.

Notice to the obligor is not required, but an obligor who renders performance to the assignor without notice of the assignment (that performance of the contract is to be rendered now to the assignee) is discharged. Obviously, the assignor cannot then keep the consideration he has received; he owes it to the assignee. But if notice is given to the obligor and she performs to the assignor anyway, the assignee can recover from either the obligor or the assignee, so the obligor could have to perform twice, as in Exercise 2 at the chapter’s end, Aldana v. Colonial Palms Plaza . Of course, an obligor who receives notice of the assignment from the assignee will want to be sure the assignment has really occurred. After all, anybody could waltz up to the obligor and say, “I’m the assignee of your contract with the bank. From now on, pay me the $500 a month, not the bank.” The obligor is entitled to verification of the assignment.

Effect of Assignment

General rule.

An assignment of rights effectively makes the assignee stand in the shoes of An assignee takes no greater rights than his assignor had. the assignor. He gains all the rights against the obligor that the assignor had, but no more. An obligor who could avoid the assignor’s attempt to enforce the rights could avoid a similar attempt by the assignee. Likewise, under UCC Section 9-318(1), the assignee of an account is subject to all terms of the contract between the debtor and the creditor-assignor. Suppose Dealer sells a car to Buyer on a contract where Buyer is to pay $300 per month and the car is warranted for 50,000 miles. If the car goes on the fritz before then and Dealer won’t fix it, Buyer could fix it for, say, $250 and deduct that $250 from the amount owed Dealer on the next installment (called a setoff). Now, if Dealer assigns the contract to Assignee, Assignee stands in Dealer’s shoes, and Buyer could likewise deduct the $250 from payment to Assignee.

The “shoe rule” does not apply to two types of assignments. First, it is inapplicable to the sale of a negotiable instrument to a holder in due course (covered in detail Chapter 23 "Negotiation of Commercial Paper" ). Second, the rule may be waived: under the UCC and at common law, the obligor may agree in the original contract not to raise defenses against the assignee that could have been raised against the assignor. Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-206. While a waiver of defenses Surrender by a party of legal rights otherwise available to him or her. makes the assignment more marketable from the assignee’s point of view, it is a situation fraught with peril to an obligor, who may sign a contract without understanding the full import of the waiver. Under the waiver rule, for example, a farmer who buys a tractor on credit and discovers later that it does not work would still be required to pay a credit company that purchased the contract; his defense that the merchandise was shoddy would be unavailing (he would, as used to be said, be “having to pay on a dead horse”).

For that reason, there are various rules that limit both the holder in due course and the waiver rule. Certain defenses, the so-called real defenses (infancy, duress, and fraud in the execution, among others), may always be asserted. Also, the waiver clause in the contract must have been presented in good faith, and if the assignee has actual notice of a defense that the buyer or lessee could raise, then the waiver is ineffective. Moreover, in consumer transactions, the UCC’s rule is subject to state laws that protect consumers (people buying things used primarily for personal, family, or household purposes), and many states, by statute or court decision, have made waivers of defenses ineffective in such consumer transactions A contract for household or domestic purposes, not commercial purposes. . Federal Trade Commission regulations also affect the ability of many sellers to pass on rights to assignees free of defenses that buyers could raise against them. Because of these various limitations on the holder in due course and on waivers, the “shoe rule” will not govern in consumer transactions and, if there are real defenses or the assignee does not act in good faith, in business transactions as well.

When Assignments Are Not Allowed

The general rule—as previously noted—is that most contract rights are assignable. But there are exceptions. Five of them are noted here.

Material Change in Duties of the Obligor

When an assignment has the effect of materially changing the duties that the obligor must perform, it is ineffective. Changing the party to whom the obligor must make a payment is not a material change of duty that will defeat an assignment, since that, of course, is the purpose behind most assignments. Nor will a minor change in the duties the obligor must perform defeat the assignment.

Several residents in the town of Centerville sign up on an annual basis with the Centerville Times to receive their morning paper. A customer who is moving out of town may assign his right to receive the paper to someone else within the delivery route. As long as the assignee pays for the paper, the assignment is effective; the only relationship the obligor has to the assignee is a routine delivery in exchange for payment. Obligors can consent in the original contract, however, to a subsequent assignment of duties. Here is a clause from the World Team Tennis League contract: “It is mutually agreed that the Club shall have the right to sell, assign, trade and transfer this contract to another Club in the League, and the Player agrees to accept and be bound by such sale, exchange, assignment or transfer and to faithfully perform and carry out his or her obligations under this contract as if it had been entered into by the Player and such other Club.” Consent is not necessary when the contract does not involve a personal relationship.

Assignment of Personal Rights

When it matters to the obligor who receives the benefit of his duty to perform under the contract, then the receipt of the benefit is a personal right The right or duty of a particular person to perform or receive contract duties or benefits; cannot be assigned. that cannot be assigned. For example, a student seeking to earn pocket money during the school year signs up to do research work for a professor she admires and with whom she is friendly. The professor assigns the contract to one of his colleagues with whom the student does not get along. The assignment is ineffective because it matters to the student (the obligor) who the person of the assignee is. An insurance company provides auto insurance covering Mohammed Kareem, a sixty-five-year-old man who drives very carefully. Kareem cannot assign the contract to his seventeen-year-old grandson because it matters to the insurance company who the person of its insured is. Tenants usually cannot assign (sublet) their tenancies without the landlord’s permission because it matters to the landlord who the person of their tenant is. Section 14.4.1 "Nonassignable Rights" , Nassau Hotel Co. v. Barnett & Barse Corp. , is an example of the nonassignability of a personal right.

Assignment Forbidden by Statute or Public Policy

Various federal and state laws prohibit or regulate some contract assignment. The assignment of future wages is regulated by state and federal law to protect people from improvidently denying themselves future income because of immediate present financial difficulties. And even in the absence of statute, public policy might prohibit some assignments.

Contracts That Prohibit Assignment

Assignability of contract rights is useful, and prohibitions against it are not generally favored. Many contracts contain general language that prohibits assignment of rights or of “the contract.” Both the Restatement and UCC Section 2-210(3) declare that in the absence of any contrary circumstances, a provision in the agreement that prohibits assigning “the contract” bars “only the delegation to the assignee of the assignor’s performance.” Restatement (Second) of Contracts, Section 322. In other words, unless the contract specifically prohibits assignment of any of its terms, a party is free to assign anything except his or her own duties.

Even if a contractual provision explicitly prohibits it, a right to damages for breach of the whole contract is assignable under UCC Section 2-210(2) in contracts for goods. Likewise, UCC Section 9-318(4) invalidates any contract provision that prohibits assigning sums already due or to become due. Indeed, in some states, at common law, a clause specifically prohibiting assignment will fail. For example, the buyer and the seller agree to the sale of land and to a provision barring assignment of the rights under the contract. The buyer pays the full price, but the seller refuses to convey. The buyer then assigns to her friend the right to obtain title to the land from the seller. The latter’s objection that the contract precludes such an assignment will fall on deaf ears in some states; the assignment is effective, and the friend may sue for the title.

Future Contracts

The law distinguishes between assigning future rights under an existing contract and assigning rights that will arise from a future contract. Rights contingent on a future event can be assigned in exactly the same manner as existing rights, as long as the contingent rights are already incorporated in a contract. Ben has a long-standing deal with his neighbor, Mrs. Robinson, to keep the latter’s walk clear of snow at twenty dollars a snowfall. Ben is saving his money for a new printer, but when he is eighty dollars shy of the purchase price, he becomes impatient and cajoles a friend into loaning him the balance. In return, Ben assigns his friend the earnings from the next four snowfalls. The assignment is effective. However, a right that will arise from a future contract cannot be the subject of a present assignment.

Partial Assignments

An assignor may assign part of a contractual right, but only if the obligor can perform that part of his contractual obligation separately from the remainder of his obligation. Assignment of part of a payment due is always enforceable. However, if the obligor objects, neither the assignor nor the assignee may sue him unless both are party to the suit. Mrs. Robinson owes Ben one hundred dollars. Ben assigns fifty dollars of that sum to his friend. Mrs. Robinson is perplexed by this assignment and refuses to pay until the situation is explained to her satisfaction. The friend brings suit against Mrs. Robinson. The court cannot hear the case unless Ben is also a party to the suit. This ensures all parties to the dispute are present at once and avoids multiple lawsuits.

Successive Assignments

It may happen that an assignor assigns the same interest twice (see Figure 14.2 "Successive Assignments" ). With certain exceptions, the first assignee takes precedence over any subsequent assignee. One obvious exception is when the first assignment is ineffective or revocable. A subsequent assignment has the effect of revoking a prior assignment that is ineffective or revocable. Another exception: if in good faith the subsequent assignee gives consideration for the assignment and has no knowledge of the prior assignment, he takes precedence whenever he obtains payment from, performance from, or a judgment against the obligor, or whenever he receives some tangible evidence from the assignor that the right has been assigned (e.g., a bank deposit book or an insurance policy).

Some states follow the different English rule: the first assignee to give notice to the obligor has priority, regardless of the order in which the assignments were made. Furthermore, if the assignment falls within the filing requirements of UCC Article 9 (see Chapter 28 "Secured Transactions and Suretyship" ), the first assignee to file will prevail.

Figure 14.2 Successive Assignments

Assignor’s Warranties

An assignor has legal responsibilities in making assignments. He cannot blithely assign the same interests pell-mell and escape liability. Unless the contract explicitly states to the contrary, a person who assigns a right for value makes certain assignor’s warranties Promises, express or implied, made by an assignor to the assignee about the merits of the assignment. to the assignee: that he will not upset the assignment, that he has the right to make it, and that there are no defenses that will defeat it. However, the assignor does not guarantee payment; assignment does not by itself amount to a warranty that the obligor is solvent or will perform as agreed in the original contract. Mrs. Robinson owes Ben fifty dollars. Ben assigns this sum to his friend. Before the friend collects, Ben releases Mrs. Robinson from her obligation. The friend may sue Ben for the fifty dollars. Or again, if Ben represents to his friend that Mrs. Robinson owes him (Ben) fifty dollars and assigns his friend that amount, but in fact Mrs. Robinson does not owe Ben that much, then Ben has breached his assignor’s warranty. The assignor’s warranties may be express or implied.

Key Takeaway

Generally, it is OK for an obligee to assign the right to receive contractual performance from the obligor to a third party. The effect of the assignment is to make the assignee stand in the shoes of the assignor, taking all the latter’s rights and all the defenses against nonperformance that the obligor might raise against the assignor. But the obligor may agree in advance to waive defenses against the assignee, unless such waiver is prohibited by law.

There are some exceptions to the rule that contract rights are assignable. Some, such as personal rights, are not circumstances where the obligor’s duties would materially change, cases where assignability is forbidden by statute or public policy, or, with some limits, cases where the contract itself prohibits assignment. Partial assignments and successive assignments can happen, and rules govern the resolution of problems arising from them.

When the assignor makes the assignment, that person makes certain warranties, express or implied, to the assignee, basically to the effect that the assignment is good and the assignor knows of no reason why the assignee will not get performance from the obligor.

- If Able makes a valid assignment to Baker of his contract to receive monthly rental payments from Tenant, how is Baker’s right different from what Able’s was?

- Able made a valid assignment to Baker of his contract to receive monthly purchase payments from Carr, who bought an automobile from Able. The car had a 180-day warranty, but the car malfunctioned within that time. Able had quit the auto business entirely. May Carr withhold payments from Baker to offset the cost of needed repairs?

- Assume in the case in Exercise 2 that Baker knew Able was selling defective cars just before his (Able’s) withdrawal from the auto business. How, if at all, does that change Baker’s rights?

- Why are leases generally not assignable? Why are insurance contracts not assignable?

Assignment of Contract Rights: Everything You Need to Know

The assignment of contract rights happens when one party assigns the obligations and rights of their part of a legal agreement to a different party. 3 min read updated on February 01, 2023

The assignment of contract rights happens when one party assigns the obligations and rights of their part of a legal agreement to a different party.

What Is an Assignment of Contract?

The party that currently holds rights and obligations in an existing contract is called the assignor and the party that is taking over that position in the contract is called the assignee. When assignment of contract takes place, the assignor usually wants to hand all of their duties over to a new individual or company, but the assignee needs to be fully aware of what they're taking on.

Only tangible things like property and contract rights can be transferred or assigned . Most contracts allow for assignment or transfer of contract rights, but some will include a clause specifying that transfers are not permitted.

If the contract does allow for assignments, the assignor isn't required to have the agreement of the other party in the contract but may transfer their rights whenever they want. Contract assignment does not affect the rights and responsibilities of either party involved in the contract. Just because rights are assigned or transferred doesn't mean that the duties of the contract no longer need to be carried out.

Even after the assignor transfers their rights to another, they still remain liable if any issues arise unless otherwise noted in an agreement with the other party.

The purpose for the assignment of contract rights is to change the contractual relationship, or privity , between two parties by replacing one party with a new party.

How Do Contract Assignments Work?

Contract assignments are handled differently depending on certain aspects of the agreement and other factors. The language of the original contract plays a huge role because some agreements include clauses that don't allow for the assignment of contract rights or that require the consent of the other party before assignment can occur.

For example, if Susan has a contract with a local pharmacy to deliver her prescriptions each month and the pharmacy changes ownership, the new pharmacy can have Susan's contract assigned to them. As long as Susan continues to receive her medicine when she needs it, the contract continues on, but now Susan has an agreement with a new party.

Some contracts specify that the liability of the agreement lies with the original parties, even if assignment of contract takes place. This happens when the assignor guarantees that the assignee will continue to perform the duties required in the contract. That guarantee makes the assignor liable.

Are Assignments Always Enforced?

Assignments of contract rights are usually enforceable, but will not be under these circumstances:

- Assignment is prohibited in the contract language, which is called an anti-assignment clause.

- Assignment of rights changes the foundational terms of the agreement.

- The assignment is illegal in some way.

If assignment of contract takes place, but the contract actually prohibits it, the assignment will automatically be voided.

When a transfer of contract rights will somehow change the basics of the contract, assignment cannot happen. For instance, if risks are increased, value is decreased, or the ability for performance is affected, the assignment will probably not be enforced by the court.

Basic Rights of Contract Assignments