Autism - List of Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

Autism, or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), refers to a broad range of conditions characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviors, speech, and nonverbal communication. Essays could explore the causes, symptoms, and treatment of autism, the experiences of individuals with autism, and societal understanding and acceptance of autism. We’ve gathered an extensive assortment of free essay samples on the topic of Autism you can find at Papersowl. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Rain Man and Autism

The film Rain man was released into theaters in 1988 and was awarded many awards along with an Academy Award. The movie starts off by showing Charlie who works as a car salesman, attempting to close on a deal involving four Lamborghinis. Charlie decides to drive with his girlfriend Susanna to ensure that this deal goes through. On the drive over Charlie receives a call telling him that his father has just passed away. Charlie and his girlfriend go his […]

Applied Behavior Analysis and its Effects on Autism

Abstract During my research i have found several studies that have been done to support the fact that Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) does in fact make a positive impact on children with Autism through discrete trials. It is based on the thought that when a child is rewarded for a positive behavior or correct social interaction the process will want to be repeated. Eventually one would phase out the reward. Dr Lovaas, who invented this method, has spent his career […]

The Unique Parenting Challenges are Faced by the Parents of Special Children

Introduction For typical children, parenting experiences are shared by other parents whereas the unique parenting challenges are faced by the parents of special children. Mobility and Inclusion of the parents as well as children are affected many a times. Even though careful analysis often reveals abilities, habitual tendency to perceive the disabilities from society’s part often hinders effective normalization and proper rehabilitation. All impose severe identity crisis and role restrictions even in knowledgeable parents.. In some conditions, as in the […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Autism in Japanese Manga and its Significance on Current Progression in J-pop Culture

Abstract In this paper I will explore and examine Autism in Manga, the social and cultural context of Autism in Manga, its movement, and importance of Tobe Keiko’s, “With the Light.” Manga is a huge part of Japanese culture and can be appreciated by so many different people. There are different types of Manga that have been specifically produced for that type of audience. In this paper, I will address the less talked about, women’s Manga or also known as […]

Speech Therapist for Autism

Abstract Autism Spectrum Disorder is a condition that consists of various challenges to an individual such as social skills, nonverbal communication, repetitive behaviors and difficulties with speech. So far doctors have not been able to find out what causes autism although it is believed that it involves both environmental and genetic factors. Autism can usually be detected at an early age, therefore giving the patient and therapist an early start to improve their verbal skills. Speech language pathologists also known […]

Virtual Reality in Regards to Health and how it Can be Life-Changing

Exploring Virtual Reality in Health Diego Leon Professor Ron Frazier October 29, 2018, Introduction When most individuals think of technology involving computers, they think it can solely involve two of the five senses we humans have – vision (sight) and hearing (audition). But what if we could interact with more than two sensorial channels? Virtual reality deals with just that. Virtual reality is defined as a “high-end user interface that involves real-time simulation and interaction through […]

Growing up with Autism

Autism is a profound spectrum disorder; symptoms, as well as severity, range. It is one of the fastest-growing developmental disorders in America. For every 68 children born in the United States, 1 is diagnosed with a neurological development disorder that impairs their ability to interact and communicate on what we constitute as normal levels. Autism is multifaceted; it affects the brain development of millions worldwide. Not only are those diagnosed on the Autism Spectrum facing difficulties, but the family members […]

Kids with Autism

In this earth we have many different lifeforms. Animals, plants, insects, and people. Humans have populated the earth all throughout it. Some people are born healthy and some are born will disorders and illnesses and diseases. One of the disorders is Autism. Autism is constantly affecting the people who have it and the people around them all over the world. So what is Autism? Autism is a disorder that impairs the ability for social interaction and communication. It is very […]

My Personal Experience of Getting to Know Asperger’s Syndrome

The beginning of this paper covers the history of Asperger’s Syndrome, followed by an explanation of what Asperger’s is. The history provides detailed insights into Hans Asperger and Leo Kanner, and their relationship to each other. Their work has significantly enriched our understanding of the research surrounding Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome. The paper also discusses the process leading to Asperger’s becoming a recognized diagnosis, including the contributions of Lorna Wing and Ulta Frita. Furthermore, it traces Asperger’s entry into the […]

Cultural Stereotypes and Autism Disorder

“It’s the fastest growing developmental disability, autism” (Murray, 2008, p.2). “It is a complex neurological disorder that impedes or prevents effective verbal communication, effective social interaction, and appropriate behavior” (Ennis-Cole, Durodoye, & Harris, 2013). “Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong disorder that may have comorbid conditions like attention deficit disorder (ADD)/attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorder, stereotypical and self-stimulatory behaviors, insomnia, intellectual disabilities, obsessive compulsive disorder, seizure disorder/epilepsy, Tourette syndrome, Tic disorders, gastrointestinal problems, and other conditions. Another certainty, […]

Understanding Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a cognitive disability that affects a person’s “communication, social, verbal, and motor skills” . The umbrella term of ASD created in 2013 by the American Psychiatric Association that covered 5 separate autism diagnosis and combined them into one umbrella term, the previous terms being Autistic Disorder, Rett syndrome, Asperger’s Disorder, Childhood disintegrative Disorder, and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. The word spectrum in the diagnosis refers to the fact that the disability does not manifest itself in […]

Defining Altruism Issue

In current society, it can be justified that the level of autonomy directly influences the amount of altruism an autistic adolescent implements. Defining Altruism: When it comes to the comprehension of socialization within the development of behaviors in adolescents, altruism is vital. Although there is no true altruism, more or less altruism can be determined based upon the involuntary actions and behaviors of an individual. In the absence of motivation, altruism cannot transpire. An altruist must have the inherent belief […]

911 Telecommunicators Response to Autism

Autism is becoming more prevalent every day. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention released new statistics in 2018. Nationally, 1 in 59 children have autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and boys are 4 (four) times more likely to have autism than girls. 1 in 37 boys and 1 in 151 girls were found to have autism. These are incredibly high statistics that will affect our communities across the United States We, as Telecommunicators, need to know how to understand and […]

Representation of Autism in the Netflix TV Show “Atypical”

In the first season of the TV show “Atypical”, the viewer meets the Gardner family, a seemingly normal family with an autistic teenage son, Sam, as the focus. This show failed initially to deviate from typical portrayals of autistic people on screens, as a white male, intellectually gifted, and seemingly unrelatable, although it seemed to try. Sam acts in ways that seem almost unbelievable for even someone with autism to, such as when he declares his love for someone else […]

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a group of developmental disorders that challenges a child’s skills in social interaction, communication, and behavior. ASD’s collective signs and symptoms may include: making little eye contact, repetitive behaviors, parallel play, unexplainable temper tantrums, misunderstanding of nonverbal cues, focused interests, and/or sensory overload. Positive symptoms of ASD may reflect above-average intelligence, excellence in math, science, or art, and the ability to learn things in detail. A question that many parent has is whAlthough an individual […]

The Complexity of Autism

Autism spectrum disorder is a complex disease that affects the developmental and speech capabilities of adolescents that carries with them to adulthood. It is distinctly apparent when the child is still very young and able to be diagnosed from about a year and a half old onwards. Although the disease cannot be pinpointed to one specific area of the brain, it is believed to stem from a glitchy gene that makes the child more susceptible to developing autism, oxygen deprivation […]

An Overview of the Five Deadly Diseases that Affect the Human Brain

There are hundreds of diseases that affect the brain. Every day, we fight these diseases just as vehemently as they afflict their carriers. Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's, depression, autism, and strokes are just five of the most lethal and debilitating diseases that afflict human brains. Parkinson's disease alone claims up to 18,000 lives a year (Hagerman 1). But what is it? Parkinson's disease occurs when a brain chemical called dopamine begins to die in a region that facilitates muscle movement. Consequently, […]

Autism Genes: Unveiling the Complexities

“Autism is a brain disorder that typically affects a person’s ability to communicate, form relationships with others and respond appropriately to the environment (www.childdevelopmentinfo.com).” There are different levels of autism. “There is the autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome and pervasive developmental syndrome (www.asws.org).” According to (www.everydayhealth.com/autism/types), “Each situation is unique as there are many levels and severities of it. Many cases also include sensory difficulties. These can range from imaginary sights and sounds to other sensations.” There are many different characteristics […]

Autism and Assistive Technology for Autistic Children

Autism is a complex neurobehavioral condition that is found in a person from early childhood days where the person faces difficulty in communicating with another person. It is also known as ASD or Autism Spectrum Disorder. It is a spectrum disorder because its effect varies from person to person. This is caused due to some changes that happen during early brain development. It is suggested that it may arise from abnormalities in parts of the brain that interpret sensory input […]

The Evolution of Autism Diagnosis: from Misunderstanding to Scientific Approach

Autism has come a long way from the early 1980s when it was rarely diagnosed to today where 100 out 10,000 kids are diagnosed. Autism is defined as a developmental disorder that affects communication and behavior (NIMH 2018). There are many aspects surrounding Autism and the underlying effects that play a role in Autism. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, people with Autism have “Difficulty with communication and interaction with other people Restricted interests and repetitive […]

Do Vaccines Cause Autism

In a world of medicines and “mommy bloggers”, there is a controversy between pro-vaxxers and anti-vaxxers. The vaccination controversy cause an uproar for many people, understandably, it’s very polarized- you strongly believe in them or you strongly do not. For me, at the age of 15, I strongly believe in the Pro-Vaccine movement and I have data that can back me up. For starters, you may wonder ‘what is a vaccine’ or ‘how to do they work’. For a general […]

Autism: Characteristics, Diagnosis, and Understanding

The prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder has nearly doubled in recent years, and the numbers are staggering: nearly 1 in every 59 children are diagnosed with autism in the United States alone. Yet, there are so many questions surrounding the complexity and increase in diagnoses of this condition that affects so many in such diverse ways. (Autism Speaks) How autism originates in the first place and its impact on communication, both verbal and nonverbal, are questions that need to be […]

Autism Spectrum Disorder and its Positive Effects

What would it feel like if you were constantly ignored or treated as though you have little usefulness? Many people experience this kind of treatment their entire lives. Long has it been assumed that people with mental disabilities such as Autism, were meant to be cared for but to never expect any value from them. Evil men such as Hitler even went so far as to kill them because he thought they had no use to society. However, there is […]

Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders and ADHD

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder that affects communication and behavior, generally diagnosed within the early stages of life. No two individuals living with Autism experience the same symptoms, as the type and severity varies with each case (Holland, 2018.). Autism has been around for hundreds of years, but the definition has evolved immensely. In 1943, scientists Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger conducted research on individuals with social and emotional deficits to better refine the definition […]

Raising a Child with Autism

All impose severe identity crisis and role restrictions even in knowledgeable parents.. In some conditions, as in the case of physical challenges, the child needs physical reassurance and support from the parents against those conditions of cognitive deficits in which the demands are always parent’s constant attention and feedback. As far as autism is concerned, the child’s deficits are many namely social, emotional, communicational, sensual, as well as behavioral. Symptoms are usually identified between one and two years of age. […]

Is Autism a Kind of Brain Damage

Many people have different views about autism. Autism may be only one simple word, but with this one word comes many forms in the way it could affect people with this disability. Autism should not be looked down on as much as this disability is from others in society. It may seem as if it has more “cons” than “pros” as some call them, but if looked at from a better perspective, there could be more pros than cons and […]

Trouble with Social Aspects and People on the Autism Spectrum

Autism in childhood starts as early as age two, and symptoms will become more severe as children continue into elementary school. When a child goes to a psychiatrist, they will work on social development. Adolescence with autism struggle when attempting to project others pain. For example, my brother has Asperger's and when I have a bone graph done on my hand, he could not stop touching my hand. He needed constant reminders to not touch and remind him of when […]

Effects of Autism

When he was eight years old, the parents of Joshua Dushack learned that their son was different. He had been diagnosed with Autism. According to the doctors, Joshua would never be able to read, write, talk, or go to school on his own. This might have been the case, had his parents accepted it. But his mother saw her son as a normal boy, and treated him as such. He did need some extra help in school, but because of […]

How Different Types of Assistive Technology Can Help Children with Autism

I. Introduction An anonymous speaker once said, “some people with Autism may not be able to speak or answer to their name, but they can still hear your words and feel your kindness.” Approximately thirty percent of people diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder never learn to speak more than a few words (Forman & Rudy, 2018). Fortunately in today’s society, new technologies have made it possible for these individuals to communicate and socialize with others. Purpose The primary focus of […]

Searching Employment Autism

Over the last 20 years, there has been an alarming increase for children who have been diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control, in the year 2000 1 in 159 children would be diagnosed with ASD. In the latest version of the study, the number has been reduced to 1 in 59 children will be diagnosed with ASD (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). This is a subject that […]

Related topic

Additional example essays.

- Eating Disorder Is a Growing Problem in Modern Society

- What Can Cause a Mental Illness is Social Problem?

- Diagnosing Bipolar Disorder

- Substance Abuse and Mental Illnesses

- The Guiltiness Of Hamlet's Mother Gertrude: Depression Is What Leads To His Death

- Social Media and Eating Disorders: Unveiling the Impact

- About Postpartum Depression In The Yellow Wallpaper

- Jane's Depression In The Yellow Wallpaper

- Insanity in The Tell Tale Heart

- Is There Too Much Pressure on Females to Have Perfect Bodies?

- Death Penalty Should be Abolished

- Personal Experience Essay about Love: The Ignition of My Soul

<h2>How To Write an Essay About Autism</h2> <h3>Understanding Autism</h3> <p>Before writing an essay about autism, it's essential to understand what autism is and the spectrum of conditions it encompasses. Autism, or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), is a complex developmental disorder that affects communication and behavior. It is characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviors, speech, and nonverbal communication. Start your essay by explaining the nature of autism, its symptoms, and the spectrum concept, which acknowledges a range of strengths and challenges experienced by individuals with autism. It's also important to discuss the causes and diagnosis of autism, as well as the common misconceptions and stereotypes surrounding it. This foundational knowledge will set the stage for a more in-depth exploration of the topic.</p> <h3>Developing a Focused Thesis Statement</h3> <p>A strong essay on autism should be centered around a clear, focused thesis statement. This statement should present a specific angle or argument about autism. For example, you might discuss the importance of early intervention and therapy, the representation of autism in media, or the challenges faced by individuals with autism in education and employment. Your thesis will guide the direction of your essay and ensure that your analysis is structured and coherent.</p> <h3>Gathering and Analyzing Data</h3> <p>To support your thesis, gather relevant data and research from credible sources. This might include scientific studies, statistics, reports from autism advocacy organizations, and personal narratives. Analyze this data critically, considering different perspectives and the quality of the evidence. Including a range of viewpoints will strengthen your argument and demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the topic.</p> <h3>Discussing Implications and Interventions</h3> <p>A significant portion of your essay should be dedicated to discussing the broader implications of autism and potential interventions. This can include the impact of autism on individuals and families, educational strategies, therapeutic approaches, and social support systems. Evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions, drawing on case studies or research findings. Discussing both the successes and challenges in managing and understanding autism will provide a balanced view and demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the topic.</p> <h3>Concluding the Essay</h3> <p>Conclude your essay by summarizing the key points of your discussion and restating your thesis in light of the evidence and examples provided. Your conclusion should tie together your analysis and emphasize the significance of understanding and supporting individuals with autism. You might also want to highlight areas where further research or development is needed or the potential for societal changes to improve the lives of those with autism.</p> <h3>Final Review and Editing</h3> <p>After completing your essay, it's important to review and edit your work. Ensure that your arguments are clearly articulated and supported by evidence. Check for grammatical accuracy and ensure that your essay flows logically from one point to the next. Consider seeking feedback from peers or experts in the field to refine your essay further. A well-crafted essay on autism will not only inform but also engage readers in considering the complexities of this condition and the collective efforts required to support those affected by it.</p>

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

BBC World Service

Listen live.

Wait Wait...Don't Tell Me

Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me! is NPR's weekly quiz program. Each week on the radio you can test your knowledge against some of the best and brightest in the news and entertainment world while figuring out what's real news and what's made up.

- Behavioral Health

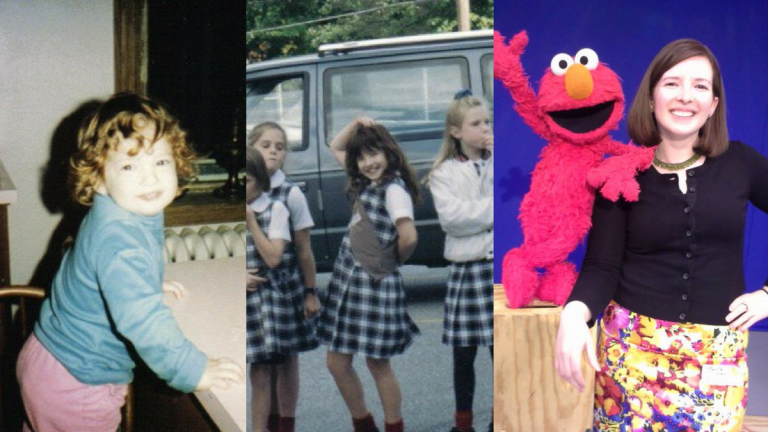

Autism found me, and then I found my voice

Since my diagnosis with autism in 2015 at age 30, a bolder, more outspoken side of myself has emerged..

- Marta Rusek

(Images courtesy of the author)

‘Coming out’ as autistic

Encouraging greater awareness and advocacy.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by Speak Easy

Thoughtful essays, commentaries, and opinions on current events, ideas, and life in the Philadelphia region.

You may also like

Orna Guralnik on ‘Couples Therapy’

The reality show 'Couples Therapy' puts real-life couples sessions with Dr. Orna Guralnik on camera. Guralnik joins us to talk about relationships and therapy.

Air Date: September 15, 2023 12:00 pm

The Secret Life of Secrets

In The Secret Life of Secrets, Michael Slepian reveals how secrets impact our minds, relationships and more, and gives strategies to make them easier to carry around with us.

Air Date: June 21, 2022 10:00 am

Corona-somnia: Sleep disorders and the global pandemic

Struggling to fall asleep or stay asleep? The stress and uncertainty of COVID-19 increased rates of insomnia, restlessness and something called revenge bedtime procrastination

Air Date: August 26, 2021 10:00 am

About Marta Rusek

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Exp Neurobiol

- v.25(1); 2016 Feb

A Short Review on the Current Understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Hye ran park.

1 Department of Neurosurgery, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul 03080, Korea.

Jae Meen Lee

Hyo eun moon, dong soo lee.

2 Department of Nuclear Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, Korea.

Bung-Nyun Kim

3 Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, Korea.

Jinhyun Kim

4 Center for Functional Connectomics, Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), Seoul 02792, Korea.

Dong Gyu Kim

Sun ha paek.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a set of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by a deficit in social behaviors and nonverbal interactions such as reduced eye contact, facial expression, and body gestures in the first 3 years of life. It is not a single disorder, and it is broadly considered to be a multi-factorial disorder resulting from genetic and non-genetic risk factors and their interaction. Genetic studies of ASD have identified mutations that interfere with typical neurodevelopment in utero through childhood. These complexes of genes have been involved in synaptogenesis and axon motility. Recent developments in neuroimaging studies have provided many important insights into the pathological changes that occur in the brain of patients with ASD in vivo. Especially, the role of amygdala, a major component of the limbic system and the affective loop of the cortico-striatothalamo-cortical circuit, in cognition and ASD has been proved in numerous neuropathological and neuroimaging studies. Besides the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens is also considered as the key structure which is related with the social reward response in ASD. Although educational and behavioral treatments have been the mainstay of the management of ASD, pharmacological and interventional treatments have also shown some benefit in subjects with ASD. Also, there have been reports about few patients who experienced improvement after deep brain stimulation, one of the interventional treatments. The key architecture of ASD development which could be a target for treatment is still an uncharted territory. Further work is needed to broaden the horizons on the understanding of ASD.

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a set of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by a lack of social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication in the first 3 years of life. The distinctive social behaviors include an avoidance of eye contact, problems with emotional control or understanding the emotions of others, and a markedly restricted range of activities and interests [ 1 ]. The current prevalence of ASD in the latest large-scale surveys is about 1%~2% [ 2 , 3 ]. The prevalence of ASD has increased in the past two decades [ 4 ]. Although the increase in prevalence is partially the result of changes in DSM diagnostic criteria and younger age of diagnosis, an increase in risk factors cannot be ruled out [ 5 , 6 ]. Studies have shown a male predominance; ASD affects 2~3 times more males than females [ 2 , 3 , 7 ]. This diagnostic bias towards males might result from under-recognition of females with ASD [ 8 ]. Also, some researchers have suggested the possibility that the female-specific protective effects against ASD might exist [ 9 ].

A Swiss psychiatrist, Paul Eugen Bleuler used the term "autism" to define the symptoms of schizophrenia for the first time in 1912 [ 10 ]. He derived it from the Greek word αὐτὀς (autos), which means self. Hans Asperger adopted Bleuler's terminology "autistic" in its modern sense to describe child psychology in 1938. Afterwards, he reported about four boys who did not mix with their peer group and did not understand the meaning of the terms 'respect' and 'polite', and regard for the authority of an adult. The boys also showed specific unnatural stereotypic movement and habits. Asperger describe this pattern of behaviors as "autistic psychopathy", which is now called as Asperger's Syndrome [ 11 ]. The person who first used autism in its modern sense is Leo Kanner. In 1943, he reported about 8 boys and 3 girls who had "an innate inability to form the usual, biologically provided affective contact with people", and introduced the label early infantile autism [ 12 ]. Hans Asperger and Leo Kanner have been considered as those who designed the basis of the modern study of autism.

Most recently, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) adopted the term ASD with a dyadic definition of core symptoms: early-onset of difficulties in social interaction and communication, and repetitive, restricted behaviors, interests, or activities [ 13 ]. Atypical language development, which had been included into the triad of ASD, is now regarded as a co-occurring condition.

As stated earlier, the development of the brain in individuals with ASD is complex and is mediated by many genetic and environmental factors, and their interactions. Genetic studies of ASD have identified mutations that interfere with typical neurodevelopment in utero through childhood. These complexes of genes have been involved in synaptogenesis and axon motility. Also, the resultant microstructural, macrostructural, and functional abnormalities that emerge during brain development create a pattern of dysfunctional neural networks involved in socioemotional processing. Microstructurally, an altered ratio of short- to long-diameter axons and disorganization of cortical layers are observed. Macrostructurally, MRI studies assessing brain volume in individuals with ASD have consistently shown cortical and subcortical gray matter overgrowth in early brain development. Functionally, resting-state fMRI studies show a narrative of widespread global underconnectivity in socioemotional networks, and task-based fMRI studies show decreased activation of networks involved in socioemotional processing. Moreover, electrophysiological studies demonstrate alterations in both resting-state and stimulus-induced oscillatory activities in patients with ASD [ 14 ].

The well-conserved sets of genes and genetic pathways were implicated in ASD, many of which contribute toward the formation, stabilization, and maintenance of functional synapses. Therefore, these genetic aspects coupled with an in-depth phenotypic analysis of the cellular and behavioral characteristics are essential to unraveling the pathogenesis of ASD. The number of genes already discovered in ASD holds the promise to translate the knowledge into designing new therapeutic interventions. Also, the fundamental research using animal models is providing key insights into the various facets of human ASD. However, a better understanding of the genetic, molecular, and circuit level aberrations in ASD is still needed [ 15 ].

Neuroimaging studies have provided many important insights into the pathological changes that occur in the brain of patients with ASD in vivo. Importantly, ASD is accompanied by an atypical path of brain maturation, which gives rise to differences in neuroanatomy, functioning, and connectivity. Although considerable progress has been made in the development of animal models and cellular assays, neuroimaging approaches allow us to directly examine the brain in vivo, and to probably facilitate the development of a more personalized approach to the treatment of ASD [ 16 ].

ASD is not a single disorder. It is now broadly considered to be a multi-factorial disorder resulting from genetic and non-genetic risk factors and their interaction.

Genetic causes including gene defects and chromosomal anomalies have been found in 10%~20% of individuals with ASD [ 17 , 18 ]. Siblings born in families with an ASD subject have a 50 times greater risk of ASD, with a recurrence rate of 5%~8% [ 19 ]. The concordance rate reaches up to 82%~92% in monozygotic twins, compared with 1%~10% in dizygotic twins. Genetic studies suggested that single gene mutations alter developmental pathways of neuronal and axonal structures involved in synaptogenesis [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. In the cases of related with fragile X syndrome and tuberous sclerosis, hyperexcitability of neocortical circuits caused by alterations in the neocortical excitatory/inhibitory balance and abnormal neural synchronization is thought to be the most probable mechanisms [ 23 , 24 ]. Genome-wide linkage studies suggested linkages on chromosomes 2q, 7q, 15q, and 16p as the location of susceptibility genes, although it has not been fully elucidated [ 25 , 26 ]. These chromosomal abnormalities have been implicated in the disruption of neural connections, brain growth, and synaptic/dendritic morphology [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Metabolic errors including phenylketonuria, creatine deficiency syndromes, adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency, and metabolic purine disorders are also account for less than 5% of individuals with ASD [ 30 ]. Recently, the correlation between cerebellar developmental patterning gene ENGRAILED 2 and autism was reported [ 31 ]. It is the first genetic allele that contributes to ASD susceptibility in as many as 40% of ASD cases. Other genes such as UBE3A locus, GABA system genes, and serotonin transporter genes have also been considered as the genetic factors for ASD [ 18 ].

Diverse environmental causative elements including pre-natal, peri-natal, and post-natal factors also contribute to ASD [ 32 ]. Prenatal factors related with ASD include exposure to teratogens such as thalidomide, certain viral infections (congenital rubella syndrome), and maternal anticonvulsants such as valproic acid [ 33 , 34 ]. Low birth weight, abnormally short gestation length, and birth asphyxia are the peri-natal factors [ 34 ]. Reported post-natal factors associated with ASD include autoimmune disease, viral infection, hypoxia, mercury toxicity, and others [ 33 , 35 , 36 ]. Table 1 summarizes the known and putative ASD-related genes and environmental factors contributing to the ASD.

In recent years, some researchers suggest that ASD is the result of complex interactions between genetic and environmental risk factors [ 37 ]. Understanding the interaction between genetic and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of ASD will lead to optimal treatment strategy.

Clinical features and Diagnosis

ASD is typically noticed in the first 3 years of life, with deficits in social behaviors and nonverbal interactions such as reduced eye contact, facial expression, and body gestures [ 1 ]. Children also manifest with non-specific symptoms such as unusual sensory perception skills and experiences, motor clumsiness, and insomnia. Associated phenomena include mental retardation, emotional indifference, hyperactivity, aggression, self-injury, and repetitive behaviors such as body rocking or hand flapping. Repetitive, stereotyped behaviors are often accompanied by cognitive impairment, seizures or epilepsy, gastrointestinal complaints, disturbedd sleep, and other problems. Differential diagnosis includes childhood schizophrenia, learning disability, and deafness [ 38 , 39 ].

ASD is diagnosed clinically based on the presence of core symptoms. However, caution is required when diagnosing ASD because of non-specific manifestations in different age groups and individual abilities in intelligence and verbal domains. The earliest nonspecific signs recognized in infancy or toddlers include irritability, passivity, and difficulties with sleeping and eating, followed by delays in language and social engagement. In the first year of age, infants later diagnosed with ASD cannot be easily distinguished from control infants. However, some authors report that about 50% of infants show behavioral abnormalities including extremes of temperament, poor eye contact, and lack of response to parental voices or interaction. At 12 months of age, individuals with ASD show atypical behaviors, across the domains of visual attention, imitation, social responses, motor control, and reactivity [ 40 ]. There is also report about atypical language trajectories, with mild delays at 12 months progressing to more severe delays by 24 months [ 40 ]. By 3 years of age, the typical core symptoms such as lack of social communication and restricted/repetitive behaviors and interests are manifested. ASD can be easily differentiated from other psychosocial disorders in late preschool and early school years.

Amygdala and ASD

The frontal and temporal lobes are the markedly affected brain areas in the individuals with ASD. In particular, the role of amygdala in cognition and ASD has been proved in numerous neuropathological and neuroimaging studies. The amygdala located the medial temporal lobe anterior to the hippocampal formation has been thought to have a strong association with social and aggressive behaviors in patients with ASD [ 41 , 42 ]. The amygdala is a major component of the limbic system and affective loop of the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit [ 43 ].

The amygdala has 2 specific functions including eye gaze and face processing [ 44 ]. The lesion of the amygdala results in fear-processing, modulation of memory with emotional content, and eye gaze when looking at human face [ 45 , 46 , 47 ]. The findings in individuals with amygdala lesion are similar to the phenomena in ASD. The amygdala receives highly processed somatosensory, visual, auditory, and all types of visceral inputs. It sends efferents through two major pathways, the stria terminalis and the ventral amygdalofugal pathway.

The amygdala comprises a collection of 13 nuclei. Based on histochemical analyses, these 13 nuclei are divided into three primary subgroups: the basolateral (BL), centromedial (CM), and superficial groups [ 42 ]. The BL group attributes amygdala to have a role as a node connecting sensory stimuli to higher social cognition level. It links the CM and superficial groups, and it has reciprocal connection with the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) [ 48 ]. The BL group contains neurons responsive to faces and actions of others, which is not found in the other two groups of amygdala [ 49 , 50 ]. The CM group consists of the central, medial, cortical nuclei, and the periamygdaloid complex. It innervates many of the visceral and autonomic effector regions of the brain stem, and provides a major output to the hypothalamus, thalamus, ventral tegmental area, and reticular formation [ 51 ]. The superficial group includes the nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract [ 42 ].

Neurochemistrial studies revealed high density of benzodiazepine/GABAa receptors and a substantial set of opiate receptors in the amygdala. It also includes serotonergic, dopaminergic, cholinergic, and noradrenergic cell bodies and pathways [ 52 ]. Since some patients with temporal epilepsy and aggressive behavior experienced improvement in aggressiveness after bilateral stereotactic ablation of basal and corticomedial amygdaloid nuclei, the role of amygdala in emotional processing, especially rage processing has been investigated [ 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 ]. Some evidences for the amygdala deficit in patients with ASD have been suggested. Post-mortem studies found the pathology in the amygdala of individuals with ASD compared to age- and sex-matched controls [ 57 , 58 , 59 ]. Small neuronal size and increased cell density in the cortical, medial, and central nuclei of the amygdala were detected in ASD patients.

Several studies proposed the use of an animal model to confirm the evidence for the association between amygdala and ASD [ 60 , 61 ]. Despite the limitation which stems from the need to prove higher order cognitive disorder, the studies suggested that disease-associated alterations in the temporal lobes during experimental manipulations of the amygdala in animals have produced some symptoms of ASD [ 62 ]. Especially, the Kluver-Bucy syndrome, which is caused by bilateral damage to the anterior temporal lobes in monkeys, has characteristic manifestations similar to ASD [ 63 , 64 ]. Monkeys with the Kluver-Bucy syndrome shows absence of social chattering, lack of facial expression, absence of emotional reactions, repetitive abnormal movement patterns, and increased aggression. Sajdyk et al. performed experiments on rats and discovered that physiological activation of the BL nucleus of the amygdala by blocking tonic GABAergic inhibition or enhancing glutamate or the stress-associated peptide corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-mediated excitation caused reduction in social behaviors [ 65 ]. On the contrary, lesioning of the amygdala or blocking amygdala excitability with glutamate antagonist increased dyadic social interactions [ 60 ]. Besides animals, humans who underwent lesioning of the amygdala showed impairments in social judgment. This phenomenon is called acquired ASD [ 66 , 67 , 68 ]. The pattern of social deficits was similar in idiopathic and acquired ASD [ 69 ]. Felix-Ortiz and Tye sought to understand the role of projections from the BL amygdala to the ventral hippocampus in relation to behavior. Their study using mice showed that the BLS-ventral hippocampus pathway involved in anxiety plays a role in the mediation of social behavior as well [ 70 ].

The individuals with temporal lobe tumors involving the amygdala and hippocampus provide another evidence of the correlation between the amygdala and ASD. Some authors reported that patients experienced autistic symptoms after temporal lobe was damaged by a tumor [ 71 , 72 ]. Also, individuals with tuberous sclerosis experienced similar symptoms including facial expression due to a temporal lobe hamartoma [ 73 ].

Although other researchers failed to find structural abnormalities in the mesial temporal lobe of autistic subjects by performing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies [ 74 , 75 , 76 ], recent development in neuroimaging has facilitated the investigation of amygdala pathology in ASD. Studies using structural MRI estimated volumes of the amygdala and related structures in individuals with ASD and age-, gender, and verbal IQ-matched healthy controls [ 77 ]. Increase in bilateral amygdala volume and reduction in hippocampal and parahippocampal gyrus volumes were noted in individuals with ASD. Also, the lateral ventricles and intracranial volumes were significantly increased in the autistic subjects; however, overall temporal lobe volumes were similar between the ASD and control groups.

There was a significant difference in the whole brain voxel-based scans of individuals with ASD and control groups [ 78 ]. Individuals with ASD showed decreased gray matter volume in the right paracingulate sulcus, the left occipito-temporal cortex, and the left inferior frontal sulcus. On the contrary, the gray matter volume in the bilateral cerebellum was increased. Otherwise, they showed increased volume in the left amygdala/periamygdaloid cortex, the right inferior temporal gyrus, and the middle temporal gyrus.

Recently, the development of functional neuroimaging also provided some evidence for the correlation between amygdala deficit and ASD. A study using Technetium-99m (Tc-99m) single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) found that regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) was decreased in the bilateral insula, superior temporal gyri, and left prefrontal cortices in individuals with ASD compared to age- and gender-matched controls with mental retardation [ 79 ]. Also, the authors found that rCBF in both the right hippocampus and amygdala was correlated with a behavioral rating subscale.

On proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in the right hippocampal-amygdala region and the left cerebellar hemisphere, autistic subjects showed decreased level of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) in both areas [ 80 ]. There was no difference in the level of the other metabolites, such as creatine and choline. This study implies that a decreased level of NAA might be associated with neuronal hypofunction or immature neurons.

These findings support the claim that amygdala might be a key structure in the development of ASD and a target for the management of the disease.

Prefrontal cortex and ASD

Frontal lobe has been considered as playing an important role in higher-level control and a key structure associated with autism. Individuals with frontal lobe deficit demonstrate higher-order cognitive, language, social, and emotion dysfunction, which is deficient in autism [ 81 ]. Recently, neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies have attempted to delineate distinct regions of prefrontal cortex supporting different aspects of executive function. Some authors have reported that the excessive rates of brain growth in infants with ASD, which is mainly contributed by the increase of frontal cortex volume [ 82 , 83 ]. Especially, the PFC including Brodmann areas 8, 9, 10, 11, 44, 45, 46, and 47 has been noted for the structure related with ASD [ 84 ]. The PFC is cytoarchitectonically defined as the presence of a cortical granular layer IV [ 85 ], and anatomically refers to the regions of the cerebral cortex that are anterior to premotor cortex and the supplementary motor area [ 86 ]. The PFC has extensive connections with other cortical, subcortical and brain stem sites [ 87 ]. It receives inputs from the brainstem arousal systems, and its function is particularly dependent on its neurochemical environment [ 88 ].

The PFC is broadly divided into the medial PFC (mPFC) and the lateral PFC (lPFC). The mPFC is further divided into four distinct regions: medial precentral cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, prelimbic and infralimbic prefrontal cortex [ 89 ]. While the lPFC is thought to support cognitive control process [ 90 ], the mPFC has reciprocal connections with brain regions involved in emotional processing (amygdala), memory (hippocampus) and higher-order sensory regions (within temporal cortex) [ 91 ]. This involvement of mPFC in social cognition and interaction implies that mPFC might be a key region in understanding self and others [ 92 ].

The mPFC involves in fear learning and extinction by reciprocal synaptic connections with the basolateral amygdala [ 93 , 94 ]. It is believed that the mPFC regulates and controls amygdala output and the accompanying behavioral phenomena [ 95 , 96 ]. Previous authors investigated how memory processing is regulated by interactions between BLA and mPFC by means of functional disconnection [ 97 , 98 ]. Disturbed communication within amygdala-mPFC circuitry caused deficits in memory processing. These informations provide support for a role of the mPFC in the development of ASD.

Nucleus Accumbens and ASD

Besides amygdala, nucleus accumbens (NAc) is also considered as the key structure which is related with the social reward response in ASD. NAc borders ventrally on the anterior limb of the internal capsule, and the lateral subventricular fundus of the NAc is permeated in rostral sections by internal capsule fiber bundles. The rationale for NAc to be considered as the potential target of DBS for ASD is its predominant role in modulating the processing of reward and pleasure [ 99 ]. Anticipation of rewarding stimuli recruits the NAc as well as other limbic structures, and the experience of pleasure activates the NAc as well as the caudate, putamen, amygdala, and VMPFC [ 100 , 101 , 102 ]. It is well known that dysfunction of NAc regarding rewarding stimuli in subjects with depression. Bewernick et al. demonstrated antidepressant effects of NAc-DBS in 5 of the 10 patients suffering from severe treatment-resistant depression [ 103 ].

Two groups reported about the neural basis of social reward processing in ASD. Schmitz et al. examined responses to a task that involved monetary reward. They investigated the neural substrates of reward feedback in the context of a sustained attention task, and found increased activation in the left anterior cingulate gyrus and left mid-frontal gyrus on rewarded trials in ASD [ 104 ]. Scott-Van Zeeland et al. investigated the neural correlates of rewarded implicit learning in children with ASD using both social and monetary rewards. They found diminished ventral striatal response during social, but not monetary, rewarded learning [ 105 ]. According to them, activity within the ventral striatum predicted social reciprocity within the control group, but not within the ASD group.

Anticipation of pleasurable stimuli recruits the NAc, whereas the experience of pleasure activates VMPFC [ 106 ]. NAc is activated by incentive motivation to reach salient goals [ 106 ]. Increased activation in the left anterior cingulate gyrus and left mid-frontal gyrus was noted during both the anticipatory and consummatory phase of the reward response [ 104 , 107 , 108 ]. However, the activity within the ventral striatum was decreased in autistic subjects, which caused impairment in social reciprocity [ 105 ].

These findings indicate that reward network function in ASD is contingent on both the temporal phase of the response and the type of reward processed, suggesting that it is critical to assess the temporal chronometry of responses in a study of reward processing in ASD. NAc might be one of the candidates as a target of DBS which is introduced as below.

Various educational and behavioral treatments have been the mainstay of the management of ASD. Most experts agree that the treatment for ASD should be individualized. Treatment of disabling symptoms such as aggression, agitation, hyperactivity, inattention, irritability, repetitive and self-injurious behavior may allow educational and behavioral interventions to proceed more effectively [ 109 ].

Increasing interest is being shown in the role of various pharmacological treatments. Medical management includes typical antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, α2-adrenergic agonists, β-adrenergic antagonist, mood stabilizers, and anticonvulsants [ 110 , 111 ]. So far, there has been no agent which has been proved effective in social communication [ 112 ]. A major factor in the choice of pharmacologic treatment is awareness of specific individual physical, behavioral or psychiatric conditions comorbid with ASD, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, mood disorder, and intellectual disability [ 113 ]. Antidepressants were the most commonly used agents followed by stimulants and antipsychotics. The high prevalence of comorbidities is reflected in the rates of psychotropic medication use in people with ASD. Antipsychotics were effective in treating the repetitive behaviors in children with ASD; however, there was not sufficient evidence on the efficacy and safety in adolescents and adults [ 114 ]. There are also alternative options including opiate antagonist, immunotherapy, hormonal agents, megavitamins and other dietary supplements [ 109 , 113 ].

However, the autistic symptoms remain refractory to medication therapy in some patients [ 115 ]. These individuals have severely progressed disease and multiple comorbidities causing decreased quality of life [ 44 , 110 ]. Interventional therapy such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) may be an alternative therapeutic option for these patients.

Two kinds of interventions have been used for treating ASD; focused intervention practices and comprehensive treatments [ 116 ]. The focused intervention practices include prompting, reinforcement, discrete trial teaching, social stories, or peer-mediated interventions. These are designed to produce specific behavioral or developmental outcomes for individual children with ASD, and used for a limited time period with the intent of demonstrating a change in the targeted behaviors. The comprehensive treatment models are a set of practices performed over an extended period of time and are intense in their application, and usually have multiple components [ 116 ].

Since it was approved by the FDA in 1997, DBS has been used to send electrical impulses to specific parts of the brain [ 117 , 118 ]. In recent years, the spectrum for which therapeutic benefit is provided by DBS has widely been expanded from movement disorders such as Parkinson's disease, essential tremor, and dystonia to psychiatric disorders. Some authors have demonstrated the efficacy of DBS for psychiatric disorders including refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, Tourette syndrome, and others for the past few years [ 119 , 120 , 121 ].

To the best of our knowledge, there have been 2 published articles of 3 patients who underwent DBS for ASD accompanied by life-threatening self-injurious behaviors not alleviated by antipsychotic medication [ 122 , 123 ]. The targets were anterior limb of the internal capsule and globus pallidus internus, only globus pallidus, and BL nucleus of the amygdala, respectively. All patients obtained some benefit from DBS. Although the first patient showed gradual re-deterioration after temporary improvement, the patient who underwent DBS of the BL nucleus experienced substantial improvement in self-injurious behavior and social communication. These experiences suggested the possibility of DBS for the treatment of ASD. For patients who did not obtain benefit from other treatments, DBS may be a viable therapeutic option. Understanding the structures which contribute to the occurrence of ASD might open a new horizon for management of ASD, particularly DBS. Accompanying development of neuroimaging technique enables more accurate targeting and heightens the efficacy of DBS. However, the optimal DBS target and stimulation parameters are still unknown, and prospective controlled trials of DBS for various possible targets are required to determine optimal target and stimulation parameters for the safety and efficacy of DBS.

ASD should be considered as a complex disorder. It has many etiologies involving genetic and environmental factors, and further evidence for the role of amygdala and NA in the pathophysiology of ASD has been obtained from numerous studies. However, the key architecture of ASD development which could be a target for treatment is still an uncharted territory. Further work is needed to broaden the horizons on the understanding of ASD.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by the Korea Institute of Planning & Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Republic of Korea (311011-05-3-SB020), by the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project (HI11C21100200) funded by Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea, by the Technology Innovation Program (10050154, Business Model Development for Personalized Medicine Based on Integrated Genome and Clinical Information) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MI, Korea), and by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean government, MSIP (2015M3C7A1028926).

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Research, clinical, and sociological aspects of autism.

- ESPA Research, Unit 133i Business Innovation Centre, The Robert Luff Laboratory, Education & Services for People With Autism Research, Sunderland, United Kingdom

The concept of autism continues to evolve. Not only have the central diagnostic criteria that define autism evolved but understanding of the label and how autism is viewed in research, clinical and sociological terms has also changed. Several key issues have emerged in relation to research, clinical and sociological aspects of autism. Shifts in research focus to encompass the massive heterogeneity covered under the label and appreciation that autism rarely exists in a diagnostic vacuum have brought about new questions and challenges. Diagnostic changes, increasing moves towards early diagnosis and intervention, and a greater appreciation of autism in girls and women and into adulthood and old age have similarly impacted on autism in the clinic. Discussions about autism in socio-political terms have also increased, as exemplified by the rise of ideas such as neurodiversity and an increasingly vocal dialogue with those diagnosed on the autism spectrum. Such changes are to be welcomed, but at the same time bring with them new challenges. Those changes also offer an insight into what might be further to come for the label of autism.

Introduction

Although there is still debate in some quarters about who first formally defined autism ( 1 ), most people accept that Kanner ( 2 ) should be credited as offering the first recognised description of the condition in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. The core diagnostic features covering issues in areas of social and communicative interaction alongside the presence of restricted and/or repetitive patterns of behaviour ( 3 ) described in his small caseload still remain central parts of the diagnosis today. The core issue of alterations in social cognition affecting emotion recognition and social attention ( 4 ) remain integral to the diagnosis of autism. The additional requirement for such behaviours to significantly impact on various areas of day-to-day functioning completes the diagnostic criteria.

From defining a relatively small group of people, the evolution of the diagnostic criteria for autism has gone hand-in-hand with a corresponding increase in the numbers of people being diagnosed. Prevalence figures that referred to 4.5 per 10,000 ( 5 ) in the 1960s have been replaced by newer estimates suggesting that 1 in 59 children (16 per 1,000) present with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in 2014 ( 6 ). The widening of the definition of autism has undoubtedly contributed to the significant increase in the numbers of people being diagnosed. It would be unacceptably speculative however, to define diagnostic changes as being the sole cause of the perceived prevalence increases.

Alongside the growth in numbers of people being diagnosed with autism so there have been changes in other areas related to autism; specifically those related to the research, clinical practice and sociological aspects of autism. Many of the changes have centred on key issues around the acceptance that autism is an extremely heterogeneous condition both in terms of presentation and also in relation to the genetic and biological complexity underlying its existence. That autism rarely exists in some sort of diagnostic vacuum is another part of the changes witnessed over the decades following the description of autism.

In this paper we highlight some of the more widely discussed changes in areas of research, clinical practice and sociological terms in relation to autism. We speculate on how such changes might also further develop the concept of autism in years to come.

Autism Research

As the definition of autism has subtly changed over the years, so ideas and trends in autism research have waxed and waned. The focus on psychology and behaviour as core descriptive features of autism has, in many respects, guided research and clinical views and opinions about the condition. Social cognition, including areas as diverse as social motivation, emotion recognition, social attention and social learning ( 4 ), remains a mainstay of research in this area. The rise of psychoanalysis and related ideas such as attachment theory in the early 20th century for example, played a huge role in the now discredited ideas that maternal bonding or cold parenting were a cause of autism. The seemingly implicit need for psychology to formulate theories has also no doubt played a role in perpetuating all-manner of different grand and unifying reasons on why autism comes about and the core nature of the condition.

As time moved on and science witnessed the rise of psychiatric genetics, where subtle changes to the genetic code were correlated with specific behavioural and psychiatric labels, so autism science also moved in the same direction. Scientific progress allowing the genetic code to be more easily and more cost-effectively read opened up a whole new scientific world in relation to autism and various other labels. It was within this area of genetic science that some particularly important discoveries were made: (a) for the vast majority of people, autism is not a single gene “disorder,” and (b) genetic polymorphisms whilst important, are not the only mechanism that can affect gene expression. Mirroring the role of genetics in other behavioural and psychiatric conditions ( 7 ), the picture that is emerging suggests that yes, there are genetic underpinnings to autism, but identifying such label-specific genetic issues is complicated and indeed, wide-ranging.

What such genetic studies also served to prove is that autism is heterogeneous. They complemented the wide-ranging behavioural profiles that are included under the diagnostic heading of autism. Profiles that ranged from those who are profoundly autistic and who require almost constant attention to meet their daily needs, to those who have jobs, families and are able to navigate the world [seemingly] with little or minimal support for much of the time.

It is this heterogeneity that is perhaps at the core of where autism is now from several different perspectives. A heterogeneity that not only relates to the presentation of the core traits of autism but also to how autism rarely manifests in a diagnostic vacuum ( 8 ). Several authors have talked about autism as part of a wider clinical picture ( 9 , 10 ) and how various behavioural/psychiatric/somatic issues seem to follow the diagnosis. Again, such a shift mirrors what is happening in other areas of science, such as the establishment of the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project ( 11 ). RDoC recognised that defining behavioural and psychiatric conditions on the basis of presented signs and symptoms does not necessarily “reflect” the relevant underlying processes and systems that might be important. It recognised that in order to deliver important clinical information about how and why a condition manifests, or the best strategies to intervene, research cannot just singularly start with the label. Science and clinical practice need more information rather than just a blanket descriptive label such as autism.

To talk about autism as a condition that also manifests various over-represented comorbid labels also asks a fundamental question: is the word “comorbidity” entirely accurate when referring to such labels? ( 12 ). Does such comorbidity instead represent something more fundamental to at least some presentations of autism or is it something that should be seen more transiently? Numerous conditions have been detailed to co-occur alongside autism. These include various behavioural and psychiatric diagnoses such as depression, anxiety and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) ( 13 ). Other more somatic based conditions such as epilepsy ( 14 ), sleep ( 15 ) and various facets of gastrointestinal (GI) functioning ( 16 ) have also been discussed in the peer-reviewed science literature. Some of these co-occurring conditions have been described in the context of specific genetic conditions manifesting autism. Issues with the BCKDK (Branched Chain Ketoacid Dehydrogenase Kinase) gene for example, have been discussed in the context of autism, intellectual (learning) disability and epilepsy appearing together ( 17 ). Such a diagnostic combination is not unusual; autism often being described as the primary diagnosis with epilepsy and learning disability seen as “add-ons.” But should this be the case? Other evidence pointing to the possibility that epilepsy might under some circumstances beget autism ( 18 ) suggests that under some circumstances, such co-occurring conditions are so much more than just co-occurring or comorbid.

Other evidence for questioning the label “comorbid” comes from various animal models of autism. Accepting that one has to be particularly careful about extrapolating from animal models of autism to the more complex presentation of autism in humans ( 19 ), various models have suggested that autism may for some, fundamentally coexist with GI or bowel issues ( 20 , 21 ). Such observations have been noted across different animal models and cover important issues such as gut motility for example, that have been talked about in the context of autism ( 22 ).

Similarly, when one talks about the behavioural and psychiatric comorbidity in the context of autism, an analogous question arises about whether comorbidity is the right term. Anxiety and depression represent important research topics in the context of autism. Both issues have long been talked about in the context of autism ( 1 , 13 , 23 ) but only in recent years have their respective “links” to autism been more closely scrutinised.

Depression covers various different types of clinical presentations. Some research has suggested that in the context of autism, depressive illnesses such as bipolar disorder can present atypically ( 24 ). Combined with other study ( 25 ) suggesting that interventions targeting depressive symptoms might also impact on core autistic features, the possibility that autism and depression or depressive symptoms might be more closely linked than hitherto appreciated arises. Likewise with anxiety in mind, similar conclusions could be drawn from the existing research literature that anxiety may be a more central feature of autism. This on the basis of connections observed between traits of the two conditions ( 26 ) alongside shared features such as an intolerance of uncertainty ( 27 ) exerting an important effect.

A greater appreciation of the heterogeneity of autism and consideration of the myriad of other conditions that seem to be over-represented alongside autism pose serious problems to autism research. The use of “autism pure” where research participants are only included into studies on the basis of not having epilepsy or not possessing a diagnosis of ADHD or related condition pose a serious problem when it comes to the generalisation of research results to the wider population. Indeed, with the vast heterogeneity that encompasses autism, one has to question how, in the context of the current blanket diagnosis of autism or ASD, one could ever provide any universal answers about autism.

Autism in the Clinic

As mentioned previously, various subtle shifts in the criteria governing the diagnosis of autism have been witnessed down the years. Such changes have led to increased challenges for clinicians diagnosing autism from several different perspectives. One of the key challenges has come about as a function of the various expansions and contractions of what constitutes autism from a diagnostic point of view. This includes the adoption of autism as a spectrum disorder in more recent diagnostic texts.

The inclusion of Asperger syndrome in the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic schedules represented an expansion of the diagnostic criteria covering autism. Asperger syndrome defined by Hans Asperger ( 28 ) as autistic features without significant language impairment and with intelligence in the typical range, was included in the text for various different reasons. Allen Frances, one of the architects of the DSM-IV schedule, mentioned the importance of having a “ specific category to cover the substantial group of patients who failed to meet the stringent criteria for autistic disorder, but nonetheless had substantial distress or impairment from their stereotyped interests, eccentric behaviors, and interpersonal problems ” ( 29 ). It is now widely accepted that the inclusion of Asperger syndrome in diagnostic texts led to an increase in the number of autism diagnoses being given.

More recent revisions to the DSM criteria covering autism—DSM-5—included the removal of Asperger syndrome as a discrete diagnosis on the autism spectrum ( 30 ). Instead, a broader categorisation of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was adopted. The reasons for the removal of Asperger syndrome from DSM-5 are complex. The removal has however generally been positively greeted as a function of on-going debates about whether there are/were important differences between autism and Asperger syndrome to require a distinction ( 31 ) alongside more recent revelations about the actions of Asperger during World War II ( 32 ). Studies comparing DSM-IV (and its smaller revisions) with DSM-5 have also hinted that the diagnostic differences between the schedules may well-impact on the numbers of people in receipt of a diagnosis ( 33 ).

Shifts in the diagnostic text covering autism represent only one challenge to autism in the clinical sense. Other important factors continue to complicate the practice of diagnosing autism. Another important issue is a greater realisation that although the presence of observable autistic features are a necessary requirement for a diagnosis of autism, such features are also apparent in various other clinical labels. Autistic features have been noted in a range of other conditions including schizophrenia ( 34 ), personality disorders ( 35 ) and eating disorders ( 36 ) for examples. Coupled with the increasingly important observation that autism rarely exists in a diagnostic vacuum, the clinical challenges to accurately diagnosing autism multiply as a result.

The additional suggestion of “behavioural profiles” within the autism spectrum adds to the complexity. Terms such as pathological demand avoidance (PDA) coined by Newson and colleagues ( 37 ) have started to enter some diagnostic processes, despite not yet being formally recognised in diagnostic texts. Including various autistic traits alongside features such as “resisting and avoiding the ordinary demands of life” and the “active use of various strategies to resist demands via social manipulation,” debate continues about the nature of PDA and its diagnostic value ( 38 ).

Early diagnosis and intervention for autism have also witnessed some important clinical changes over the years. Driven by an acceptance of the idea that earlier diagnosis means that early intervention can be put in place to “ameliorate” some of the more life-changing effects of autism, there has been a sharp focus on the ways and means of identifying autism early and/or highlighting those most at risk of a diagnosis. It's long been known that there is a heritable aspect to autism, whether in terms of traits or diagnosis ( 39 ). In this respect, preferential screening for autism in younger siblings when an older child has been diagnosed is not an uncommon clinical sentiment ( 40 ). Other work looking at possible “red flags” for autism, whether in behaviour ( 41 ) or in more physiological terms still continue to find popularity in both research and clinical terms.

But still however, autism continues to confound. As of yet, there are only limited reliable red flags to determine or preclude the future presence of autism ( 42 ). Early behavioural interventions for autism have not yet fulfilled the promise they are said to hold ( 43 ) and autism is not seemingly present in the earliest days of development for all ( 44 , 45 ). There is still a way to go.

Autism in a modern clinical sense is also witnessing change in several other quarters. The traditional focus of autism on children, particularly boys, is being replaced by a wider acceptance that (a) autism can and does manifest in girls and women, and (b) children with autism age and mature to become adults with autism. Even the psychological mainstay of autism—issues with social cognition—is undergoing discussion and revision.

On the issue of autism presentation in females, several important themes are becoming more evident. Discussions about whether there may be subtle differences in the presentation of autism in females compared to males are being voiced, pertinent to the idea that there may be one or more specific female phenotypes of autism ( 46 ). Further characterisation has hinted that sex differences in the core domain of repetitive stereotyped behaviours ( 47 ) for example, may be something important when it comes to assessing autism in females.

Allied to the idea of sex differences in autism presentation, is an increasing emphasis on the notion of camouflaging or masking ( 48 ). This masking assumes that there may active or adaptive processes on-going that allow females to hide some of their core autistic features and which potentially contributes to the under-identification of autism. Although some authors have talked about the potentially negative aspects of masking in terms of the use of cognitive resources to “maintain the mask,” one could also view such as adaptation in a more positive light relating to the learning of such a strategy as a coping mechanism. Both the themes of possible sex differences in presentation and masking add to the clinical complexity of reliably assessing for autism.

Insofar as the growing interest in the presentation of autism in adulthood, there are various other clinical considerations. Alongside the idea that the presentation of autism in childhood might not be the same as autism in adulthood ( 49 ), the increasing number of people receiving a diagnosis in adulthood is a worthy reminder that autism is very much a lifelong condition for many, but not necessarily all ( 50 ). The available research literature also highlights how autism in older adults carries some unique issues ( 51 ) some of which will require clinical attention.

Insofar as the issue of social cognition and autism, previous sweeping generalisations about a deficit in empathy for example, embodying all autism are also being questioned. Discussions are beginning debating issues such as how empathy is measured and whether such measurements in the context of autism are as accurate as once believed ( 52 ). Whether too, the concept of social cognition and all the aspects it encompasses is too generalised in its portrayal of autism, including the notion of the “double empathy problem” ( 53 ) where reciprocity and mutual understanding during interaction are not solely down to the person with autism. Rather, they come about because experiences and understanding differ from an autistic and non-autistic point of view. Such discussions are beginning to have a real impact on the way that autism is perceived.

Autism in Sociological Terms

To talk about autism purely through a research or clinical practice lens does not do justice to the existing peer-reviewed literature in its entirety. Where once autism was the sole domain of medical or academic professionals, so now there is a growing appreciation of autism in socio-political terms too, with numerous voices from the autism spectrum being heard in the scientific literature and beyond.

There are various factors that have contributed to the increased visibility of those diagnosed with autism contributing to the narrative about autism. As mentioned, the fact that children with autism become autistic adults is starting to become more widely appreciated in various circles. The expansion of the diagnostic criteria has also played a strong role too, as the diagnostic boundaries of the autism spectrum were widened to include those with sometimes good vocal communicative abilities. The growth in social media and related communication forms likewise provided a platform for many people to voice their own opinions about what autism means to them and further influence discussions about autism. The idea that autistic people are experts on autism continues to grow ( 54 ).

For some people with autism, the existing narrative about autism based on a deficit model (deficits in socio-communicative abilities for example) is seemingly over-emphasised. The existing medical model of autism focusing such deficits as being centred on the person does not offer a completely satisfying explanation for autism and how its features can disable a person. Autism does not solely exist in a sociological as well as diagnostic vacuum. In this context, the rise and rise of the concept of neurodiversity offered an important alternative to the existing viewpoint.

Although still the topic of some discussion, neurodiversity applied to autism is based on several key tenets: (a) all minds are different, and (b) “ neurodiversity is the idea that neurological differences like autism and ADHD are the result of normal, natural variation in the human genome ” ( 55 ). The adoption of the social model of disability by neurodiversity proponents moves the emphasis on the person as the epicentre of disability to that where societal structures and functions tend to be “ physically, socially and emotionally inhospitable towards autistic people ” ( 56 ). The message is that subtle changes to the social environment could make quite a lot of difference to the disabling features of autism.

Although a popular idea in many quarters, the concept of neurodiversity is not without its critics both from a scientific and sociological point of view ( 57 ). Certain key terms often mentioned alongside neurodiversity (e.g., neurotypical) are not well-defined or are incompatible with the existing research literature ( 58 ). The idea that societal organisation is a primary cause of the disability experienced by those with the most profound types of autism is also problematic in the context of current scientific knowledge and understanding. Other issues such as the increasing use of self-diagnosis ( 59 ) and the seeming under-representation of those with the most profound forms of autism in relation to neurodiversity further complicate the movement and its aims.

The challenges that face the evolving concept of neurodiversity when applied to autism should not however detract from the important effects that it has had and continues to have. Moving away from the idea that autistic people are broken or somehow incomplete as a function of their disability is an important part of the evolution of autism. The idea that autism is something to be researched as stand-alone issue separate from the person is something else that is being slowly being eroded by such a theory.

The concept of autism continues to evolve in relation to research, clinical practice and sociological domains. Such changes offer clues as to the future directions that autism may take and the challenges that lie ahead.