Advertisement

Current and Emerging Therapies for Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Narrative Review

- Open access

- Published: 29 June 2023

- Volume 13 , pages 1647–1660, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gil Yosipovitch 1 ,

- Georgia Biazus Soares 1 &

- Omar Mahmoud 1

5896 Accesses

5 Citations

17 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a condition in which wheals, angioedema, and pruritus occur spontaneously and recurrently for at least 6 weeks. The etiology of this disease is partially dependent on production of autoantibodies that activate and recruit inflammatory cells. Although the wheals can resolve within 24 h, symptoms have a significant detrimental impact on the quality of life of these patients. Standard therapy for CSU includes second-generation antihistamines and omalizumab. However, many patients tend to be refractory to these therapies. Available treatments such as cyclosporine, dapsone, dupilumab, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa) inhibitors have been used with success in some cases. Furthermore, various biologics and other novel drugs have emerged as potential treatments for this condition, and many more are currently under investigation in randomized clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Literature Review

Treatment of severely recalcitrant chronic spontaneous urticaria: a discussion of relevant issues.

Targeted Therapy for Chronıc Spontaneous Urtıcarıa: Ratıonale and Recent Progress

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is a debilitating disease that can negatively impact quality of life |

Few therapies are approved for this condition, and patients can be refractory to these treatments |

In this article, we highlight the various novel drugs that are currently being studied in clinical trials for this disease |

Introduction

Chronic urticaria is characterized by wheals, angioedema, or both that occur continuously or sporadically for at least 6 weeks. The wheals are intensely pruritic, resolve in < 24 h, and tend to recur on a daily basis [ 1 ]. Chronic urticaria typically lasts for 2–5 years before spontaneously resolving [ 2 ]. The point prevalence of the disease ranges from 0.23 to 0.70% in different studies, and it most commonly affects women [ 3 , 4 ]. Pruritus in these patients frequently occurs on a daily basis, with many patients reporting increased itching at night. It most commonly occurs on the back, upper extremities, and lower extremities and is often accompanied by a heat sensation [ 5 ]. Chronic urticaria can cause physical and emotional functional impairments as well as sleep disturbances, fatigue, and irritability due to pruritus, leading to significantly reduce quality of life in these patients [ 6 ]. Patients have also been shown to suffer from psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, and somatoform disorders at higher rates than controls [ 7 ].

Chronic urticaria can be further classified as chronic inducible urticaria (CIU), in which symptoms are evoked by temperature changes or pressure, or chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), in which lesions occur spontaneously [ 1 ]. The pathogenesis of CSU is thought to involve an autoimmune component that can be characterized by the presence of IgE autoantibodies (type I or autoallergic) or IgG autoantibodies (type IIb) [ 8 ]. Both of these endotypes involve mast cell activation, which is the hallmark of the disease and leads to vasodilation, recruitment of inflammatory cells, and sensory neural activation [ 8 ]. Other mechanisms are also thought to play a role in the etiology of CSU, including alterations in the coagulation cascade, vitamin D deficiency, and infections [ 9 ]. d -dimer levels have been suggested to be a biomarker of CSU severity and may help clinicians in decision making about escalating to more aggressive treatment with biologics or higher medication doses [ 10 , 11 ].

While guidelines that contain a stepwise treatment algorithm with mainstay CSU therapies were recently published, a myriad of drugs have emerged as effective treatments for CSU, and many more are currently under investigation [ 12 ]. In this review, we will discuss available treatments for CSU as well as novel therapies that could provide promising outcomes.

A literature review was performed on PubMed to retrieve relevant English-language articles on the mentioned chronic spontaneous urticaria treatments between 2010 and 2023. The national clinical trial database ClinicalTrials.gov was used to obtain information regarding any ongoing clinical trials. References and citations from retrieved articles were also assessed to obtain other relevant literature. The considered relevant papers were accessed and included in the review. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Current and Available Treatments

Second-generation h1-antihistamines (sgahs).

Second-generation H1-antihistamines (sgAHs) such as loratadine, desloratadine, cetirizine, and levocetirizine are the first-line treatment for CSU. These are preferred over first-generation antihistamines for they selectively block peripheral receptors, therefore causing fewer side effects, including sedation and anticholinergic effects [ 9 ]. In general, no significant differences are seen between the different sgAHs in controlling CSU symptoms [ 13 ]. Standard doses of antihistamines may not provide relief for many CSU patients, however, with a recent study reporting a response rate of only 38.6% [ 14 ]. Guidelines recommend that the dose should be increased up to fourfold in patients who do not adequately respond to standard doses, with bilastine, fexofenadine, levocetirizine, and cetirizine having good-quality evidence for up-dosing [ 12 , 15 ]. Dose escalation by two- or four-fold has been shown to lead to complete remission in 63.2% of CSU cases [ 14 ]. Furthermore, a cohort study of 175 pediatric chronic urticaria patients showed that 92% of cases were well controlled with sgAHs, and these medications were found to have a favorable safety profile in randomized controlled trials (RTCs) evaluating children [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. The addition of a second sgAH or another medication such as a H2-antihistamine or leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) can also be considered in certain cases [ 19 ]. The addition of LTRA montelukast to first-line therapy with sgAHs, for example, was found to be particularly effective in patients with angioedema-predominant CSU, leading to disease resolution in about two-thirds of cases [ 20 ].

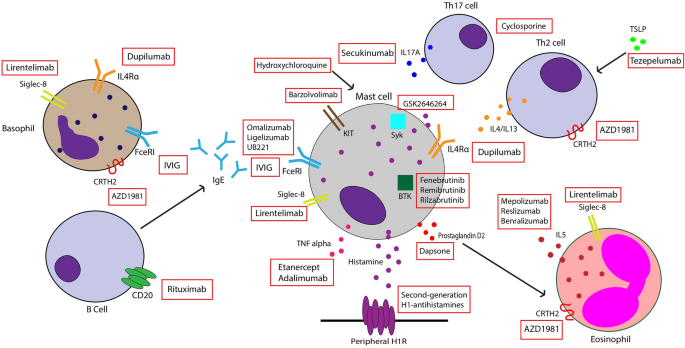

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against IgE that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of antihistamine-refractory CSU. It works by binding to free IgE and inhibiting interaction with the FcεRI receptor on basophils and mast cells, thus preventing their activation (Fig. 1 ). It also increases free IgE levels, leading to downregulation of FcεRI receptors [ 9 ]. Many RTCs have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of omalizumab in CSU patients. One meta-analysis including seven trials reported that patients treated with omalizumab had significantly reduced itch scores and wheal scores compared to placebo, with the strongest reduction in weekly itch scores seen in those taking 300 mg every 4 weeks [ 21 ]. Improvements in quality of life are also seen with this therapy, with one systematic review reporting an improvement of 13.12 points on a scale of 23–115 using the validated chronic urticaria quality of life questionnaire [ 22 ].

Mechanism of action of some existing and novel therapies for chronic spontaneous urticaria

The response to treatment may vary depending on a patient’s disease endotype. Patients with type I CSU who have IgE autoantibodies against allergens such as thyroperoxidase (TPO) usually respond quickly and effectively to omalizumab. A RTC assessing patients who had antihistamine-refractory CSU and IgE anti-TPO reported that 70.4% of patients demonstrated complete protection from wheal development compared to 4.5% in the placebo group, and complete absence of pruritus was seen in 59.3% of patients compared to 9.1% of controls [ 23 ]. Those with type IIb CSU are less likely to respond to omalizumab and have delayed onset of response to the drug [ 8 ]. Many studies have shown that patients who partially respond to the standard dose of 300 mg every 4 weeks can benefit from dose increases [ 24 ]. Omalizumab is generally well tolerated, and the most common adverse effects include injection site reactions, viral infections, upper respiratory infections, sinusitis, and headaches [ 25 ]. Patient monitoring is often recommended after the first three doses of the drug because anaphylaxis—although rare—is more likely to occur within this time frame [ 26 ]. In the last 2 years, the FDA has also approved home self-administration of omalizumab [ 27 ].

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine is an immunosuppressant that has been used as an off-label add-on therapy in patients who are refractory to monotherapy with antihistamines or omalizumab [ 9 ]. A meta-analysis evaluating efficacy of cyclosporine in CSU revealed a significant change from baseline in mean urticaria activity score (which measures the intensity of wheals and pruritus) for those taking cyclosporine compared to placebo [ 28 ]. However, Savic et al. found that omalizumab was superior to cyclosporine in disease resolution and quality of life improvements [ 29 ]. Patients with biomarkers indicative of type IIb CSU were found to have quicker and more favorable response to cyclosporine [ 30 ]. There are a variety of adverse effects associated with this agent, including nausea, vomiting, headaches, hypertension, and nephrotoxicity, and many of these are dose-dependent. Although most side effects resolve with dose reduction, they have been shown to lead to treatment discontinuation in up to 18.1% of CSU patients [ 28 ].

Other immunosuppressants

Other immunosuppressants such as methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) have been used off-label to treat CSU. MTX did not demonstrate efficacy as an add-on treatment to antihistamines in randomized clinical trials [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Azathioprine has been shown to reduce chronic urticaria symptoms and was reported to be efficacious in patients with refractory CSU [ 34 , 35 ]. Furthermore, small studies have shown that MMF improved urticarial symptoms in 88% of patients with CSU and that it significantly decreased the number of wheals and itch severity in patients refractory to antihistamines and corticosteroids [ 36 , 37 ].

Dapsone is a sulfone antibiotic that has been used to treat various dermatologic conditions, and its anti-inflammatory properties could be helpful in treating CSU. In a small open study of 11 refractory CSU patients, 9 patients experienced a complete response after 3 months of treatment with dapsone and cetirizine [ 38 ]. The effect of dapsone has been reported to last as long as 1 year, with a case report showing no recurrence in CSU symptoms despite discontinuation of all treatments [ 39 ]. Treatment with dapsone for 6 weeks showed a significant reduction in both itch and visual analog scale (VAS) ratings of urticaria severity compared to placebo in a cohort of antihistamine-refractory patients. However, only 3 out of 22 patients showed complete resolution of pruritus and hives with this therapy [ 40 ]. A retrospective chart review by Liang et al. found that 78% of patients with CSU improved with dapsone therapy, and 44% of these patients achieved complete response after a mean time of 5.2 months. Adverse effects were mild and most commonly included reticulocytosis and anemia [ 41 ]. Furthermore, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that treatment with dapsone resulted in a large increase in clinical improvement, although it caused little to no difference in remission rates [ 42 ]. The authors of these studies concluded that dapsone is an effective second-line treatment modality in CSU patients.

Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is an antimalarial drug that is useful in managing some autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. Although its mechanism of action in CSU is not well understood, several studies have shown it can reduce symptoms in these patients. A study evaluating antihistamine-refractory CSU patients found that 20.8% of patients who received hydroxychloroquine daily in addition to H1-antihhistamines experienced disease remission at 12 weeks compared to no patients achieving remission in the placebo group (antihistamines only) [ 43 ]. Furthermore, there were significant improvements in severity scores and quality of life in those treated with HCQ compared to placebo. However, no significant difference was found in urticarial severity scores or urticarial responses between HCQ and a leukotriene receptor antagonist in a follow-up study [ 43 ]. Other studies have also found that HCQ improves the quality of life in CSU [ 44 ]. A recent retrospective chart review including a cohort of 264 refractory CSU patients found that although omalizumab add-on therapy was associated with a higher rate of complete response, 66% of patients on HCQ achieved complete, sustained disease response at 1 year. No retinal abnormalities were found on serial visual field testing in those treated with HCQ. Therefore, the study found that HCQ is an acceptable alternative to omalizumab, especially due to its lower cost [ 45 ].

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)

IVIG is a polyvalent antibody product derived from plasma of healthy donors. Its various effects on the immune system include inactivating autoreactive T cells, downregulating B-cell antibody production, and blocking FcεR-mediated activity (Fig. 1 ) [ 46 ]. IVIG has been used in the treatment of autoimmune disorders and was proposed for treatment of refractory CSU by O’Donnell et al., who reported significant improvement in urticaria activity scores after IVIG treatment compared to baseline [ 47 ]. In another case series, administration of IVIG led to remission after 12 months in four out of six patients. Many of these patients experienced a decrease in urticaria activity score after 1–3 cycles of treatment. Adverse effects included headache, chills, fever, and increased blood pressure [ 46 ]. Another study found that 73% of patients had complete remission of symptoms with use of IVIG every 4 weeks, although the number of infusions needed to achieve disease control varied widely between patients [ 48 ]. However, no randomized clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of this therapy in CSU patients, and more robust data are needed to support its use.

Autologous serum therapy

Autologous serum therapy (AST) involves injecting a patient’s own serum subcutaneously or intramuscularly (IM). Studies have showed mixed results in the efficacy of IM AST in patients with a positive autologous serum skin test (ASST). In a study with 66 CSU patients, AST therapy led to significant improvement in disease activity after 8 weeks [ 49 ]. However, another prospective study found that, after 12 weeks, only 12% of patients experienced partial or complete remission with this therapy [ 50 ]. Subcutaneous AST has been reported to significantly decrease urticarial activity scores (UAS) and to improve quality of life in CSU patients [ 51 , 52 ].

Inhibition of Th2 cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13 leads to decreased IgE production and limited activation of mast cells and basophils, all of which play a role in CSU pathogenesis. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody against IL-4/13Rα that has been used off-label for the treatment of CSU. It has been shown to be effective within 3 months in patients with refractory CSU, with a case series reporting that 67% of patients started on dupilumab remained in remission after treatment discontinuation [ 53 ]. Results from a phase III RTC show that patients on a standard dose of antihistamines who received add-on dupilumab reported significant changes in itch severity scores and urticaria activity scores compared to those treated with antihistamine monotherapy [ 54 ]. Other RTCs to further evaluate dupilumab efficacy and safety in CSU patients are currently ongoing, and further studies are needed to assess dupilumab therapy in omalizumab-refractory patients [ 8 , 9 ].

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody against CD20 on B cells and has been proposed as an alternative therapy in CSU patients because of its potential ability to inhibit IgG autoantibodies against FcεRI or IgE [ 55 ]. There have been several case reports in which rituximab has been successfully used to treat refractory CSU [ 56 , 57 , 58 ].One phase I/II open-label trial aimed to assess rituximab use in these patients but was terminated because of safety concerns [ 9 ]. Currently, more data are needed to support the use of this drug in CSU patients.

TNFa Inhibitors

Mast cell activation leads to the release of various inflammatory mediators, including TNFa. TNFa production is increased in CSU patients, and these patients also have increased TNFa expression in both lesional and nonlesional skin compared to healthy controls [ 59 , 60 ]. Furthermore, serum levels of TNFa are positively correlated to disease severity assessed by the UAS [ 61 ]. TNFa inhibitors such as etanercept and adalimumab commonly used for psoriasis have been tried off-label in CSU patients. One retrospective study reported 60% of patients had complete or almost complete symptom resolution after treatment with TNFa inhibitors, and many had sustained responses with a mean of 13 months [ 62 ]. TNFa inhibitors have also been used to successfully treat immunosuppressive-refractory CSU patients, and even led to disease remission in three out of six cases [ 63 ]. However, RTCs with a larger study population are needed to provide a better assessment of the efficacy and safety of these agents in CSU.

Secukinumab

IL-17 is implicated in cutaneous diseases such as psoriasis, and it may also play a role in the pathogenesis of CSU. Levels of this cytokine were found to be elevated in the serum of CSU patients and correlated with disease activity [ 64 , 65 ]. IL-17 is also highly expressed in both lesional and nonlesional skin of CSU patients compared to controls, with increased IL-17A expression observed in skin mast cells [ 66 ]. This indicates that IL-17 may contribute to the increased mast cell degranulation seen in this disease. Secukinumab, an IL-17 inhibitor, was used to treat eight patients who were refractory to standard CSU treatments. The intensity of wheals and pruritus—measured by the urticaria activity score—was significantly reduced by 55% from baseline after 30 days, and by 82% after 90 days, and patients remained in remission throughout the duration of therapy [ 66 ]. More studies evaluating this drug in CSU patients are warranted.

Novel Therapies and Therapies Under Development

Anti-ige monoclonal antibodies: ligelizumab, ub221.

Ligelizumab is a novel humanized monoclonal anti-IgE antibody that works by binding to IgE with a much higher affinity than omalizumab. It has been shown that this drug is more potent than omalizumab at suppressing free IgE levels and at reducing expression of FcεRI and IgE on basophils [ 67 ]. A phase IIb study evaluated three doses of ligelizumab (24 mg, 72 mg, and 240 mg) and found that this drug achieved complete symptom control in up to 44% of CSU patients by week 12 compared to 26% of patients taking omalizumab [ 68 ]. Furthermore, the percentage of patients achieving a weekly itch severity score of 0 was higher in all ligelizumab groups compared to omalizumab at week 12 [ 68 ]. An extension, open-label study was subsequently performed and demonstrated sustained efficacy of the drug, with 84.2% of patients having cumulatively achieved minimal disease activity by week 52 [ 69 ]. A multicenter phase III RTC evaluating the use of this drug in adolescents and adults with CSU and comparing ligelizumab with omalizumab has recently been completed. Preliminary data confirm the efficacy of ligelizumab in CSU patients compared to placebo, although it did not find this drug to be superior to omalizumab when assessing changes from baseline in urticaria activity scores at week 12 (NCT03580369, https://www.hcplive.com/view/phase-3-ligelizumab-not-superior-omalizumab ). A phase III clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of ligelizumab in CSU was recently terminated, but this was not due to safety concerns (NCT04210843). Ligelizumab was found to have a favorable safety profile, with the most common adverse events being injection site reactions, nasopharyngitis, headache, upper respiratory tract infection, and urticaria [ 69 ].

UB221 is a monoclonal antibody that binds to CD23-bound IgE, thus downregulating CD23-mediated IgE production. It also binds to IgE with higher affinity than omalizumab, with a rapid reduction in serum IgE observed after one IV dose of UB221 in mice models [ 70 ]. UB221 is currently under investigation in phase I and phase II studies as a potential add-on therapy for patients with CSU (Table 1 ) (NCT03632291, NCT05298215). Other RTCs evaluating the pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of UB221 are also underway (NCT04175704, NCT04404023).

Bruton Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) inhibitors: Fenebrutinib, Remibrutinib, Rilzabrutinib

BTK is an enzyme involved in FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation, basophil signaling, and B-cell functioning. BTK inhibitors prohibit IgE-mediated responses and thus can be a useful therapy in CSU patients [ 8 , 55 ]. Fenebrutinib is a highly selective BTK inhibitor that is given orally and was recently evaluated in a phase II RTC for treatment of antihistamine-resistant CSU. By week 8, improvements in urticarial activity scores were seen in patients randomized to 200 mg twice daily and 150 mg daily but not 50 mg daily compared to placebo. This response was dose-dependent, with 39% of patients taking 200 mg twice daily achieving complete response at week 8 compared to 25% of those taking 150 mg daily and 4% of those taking the placebo [ 71 ]. Adverse effects were minimal and most commonly included headache, urticaria, and nasopharyngitis [ 71 ]. Remibrutinib, another potent oral BTK inhibitor, was also found to improve antihistamine-resistant CSU symptoms in a phase II RTC. Multiple doses were tested, and all were found to significantly reduce urticaria activity symptom scores. Improvement was observed as early as week 1 and maintained through the end of the study at week 12 [ 72 ]. This agent was also shown to improve the quality of life in CSU patients, with significant improvements in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores observed at week 12 compared to placebo [ 73 ]. The efficacy and safety of BTK inhibitor rilzabrutinib are currently being assessed in a phase II RTC (NCT05107115).

Anti-IL5 Monoclonal Antibodies: Mepolizumab, Reslizumab, Benralizumab

Cutaneous eosinophilic infiltration secondary to mast cell recruitment via IL-5 may contribute to the pathogenesis of CSU, for these patients have increased eosinophils in both lesional and nonlesional skin compared to controls [ 74 , 75 ]. Mepolizumab, an anti-IL5 monoclonal antibody, is approved for treatment of eosinophilic asthma and has been used off-label to treat CSU [ 76 ]. A current phase I open-label study is underway to assess the efficacy of 10 weeks of mepolizumab therapy in these patients (NCT03494881). Reslizumab, another monoclonal antibody that targets IL-5, led to sustained improvement in urticarial symptoms in a patient with angioedema-predominant CSU 4 weeks after starting treatment [ 77 ]. Furthermore, the anti-IL5 receptor antibody benralizumab has also been investigated as a potential therapy for CSU. Benralizumab was administered in 3 monthly injections to a cohort of 12 CSU patients who were refractory to antihistamines. After the three doses, the urticarial activity score decreased significantly by 15.7 points, and five patients achieved complete response at the end of the study [ 78 ]. In an ongoing phase II RTC, benralizumab induction and maintenance dosing regimens are being evaluated in a cohort of adult patients who were refractory to antihistamines (NCT04612725).

Tezepelumab

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is a cytokine that promotes Th2 inflammation. TSLP expression was shown to be increased in lesional skin of patients with CSU, indicating it may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease [ 79 ]. Therefore, blocking TSLP action with drugs such as the monoclonal antibody tezepelumab may be useful in reducing inflammation in CSU. The INCEPTION study, a phase II RTC evaluating the efficacy of tezepelumab in adult CSU patients compared to omalizumab and placebo, is currently underway but no results have been published (NCT04833855).

Lirentelimab

Sialic acid-binding, immunoglobulin-like lectin (Siglec)-8 is an inhibitory receptor selectively expressed on mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils (Fig. 1 ). Binding of monoclonal antibodies to this receptor leads to apoptosis of eosinophils and inhibition of FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation [ 80 ]. Due to its mechanism of action, lirentelimab, an anti-Siglec-8 monoclonal antibody, has been explored as a treatment for CSU. In a phase II study, both omalizumab-naïve and -resistant CSU patients were treated with intravenous infusions of lirentelimab. Patients experienced symptomatic improvement and decreases in urticaria activity scores from baseline at week 22. Furthermore, 95% of omalizumab-naïve and 46% of omalizumab-refractory CSU patients experienced complete response at week 22. The most common adverse events included infusion-related reactions, nasopharyngitis, and headache [ 81 ]. A study to assess subcutaneous liretenlimab in adult CSU patients is ongoing (NCT05528861).

Chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 cells (CRTH2) is a prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) receptor expressed on basophils, eosinophils, and some Th2 cells. By binding to CRTH2, PGD2—which is released by mast cells—leads to activation and chemotaxis of eosinophils and basophils [ 80 ]. Increased eosinophilic CRTH2 expression has been reported in allergic skin diseases, including chronic urticaria and atopic dermatitis [ 82 ]. However, Oliver et al. found decreased CRTH2 expression on blood basophils and eosinophils of CSU patients, which they speculated could be due to in vivo PGD2 activation [ 83 ]. The oral selective CRTH2 antagonist AZD1981 has been investigated in antihistamine-resistant CSU patients and was found to have a greater effect on weekly itch scores than on hives during a 4-week treatment period and into the washout period [ 84 ]. Treatment with AZD1981 was also found to increase circulating eosinophils and reduce PGD2-mediated eosinophil shape change [ 84 ]. More studies are needed to evaluate the long-term efficacy of this agent in CSU.

Barzolvolimab

The KIT receptor and its ligand stem cell factor (SCF) are important regulators of mast cell differentiation, maturation, and survival. Barzolvolimab is a monoclonal anti-KIT antibody and is a promising new treatment for CSU patients. A study in healthy human volunteers showed that barzolvolimab inhibits SCF-dependent mast cell activation and leads to systemic mast cell ablation [ 85 ]. A recently published abstract of an ongoing phase I clinical trial reported that CSU patients receiving IV barzolvolimab had dose-dependent improvements in urticarial activity score by week 8 of treatment [ 86 ]. A phase II study assessing this novel therapy in CSU patients is currently underway (NCT05368285).

Spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) is involved in signal transduction in various immune cells and plays an important role in FcεRI signaling and activation of mast cells [ 80 ]. The selective, topical Syk inhibitor GSK2646264 has been shown to decrease histamine release from skin mast cells, indicating that this therapy could potentially be used in CSU patients [ 87 ]. A phase I study evaluating GSK2646264 in healthy volunteers, cold urticaria, and CSU patients found that the drug was well tolerated but no conclusions could be made about changes in urticaria activity score due to the low number of CSU patients recruited [ 88 ]. More studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of GSK2646264 in these patients.

Limitations

The main limitation of this narrative review is that it does not directly compare the efficacy of different treatment modalities between studies. Therefore, we are unable to provide data on which therapies are the most effective new treatments for CSU.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is a debilitating disease that can negatively impact the quality of life of patients. Although antihistamines and omalizumab are the recommended therapies for this condition, many patients continue to experience hives and pruritus despite the use of these treatments. Many novel therapies are currently being investigated for use in CSU, and the results of some clinical trials show great promise. Overall, more studies are needed to assess the efficacy and safety of these emerging drugs.

Lang DM. Chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(9):824–31.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Greaves M. Chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(4):664–72.

Fricke J, et al. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy. 2020;75(2):423–32.

PubMed Google Scholar

Wertenteil S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence estimates for chronic urticaria in the United States: a sex-and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):152–6.

Yosipovitch G, Ansari N, Goon A, Chan Y, Goh C. Clinical characteristics of pruritus in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(1):32–6.

Dias GAC, et al. Impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life of patients followed up at a university hospital. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:754–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Özkan M, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99(1):29–33.

Kolkhir P, Church MK, Weller K, Metz M, Schmetzer O, Maurer M. Autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria: what we know and what we do not know. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(6):1772-1781.e1.

He L, Yi W, Huang X, Long H, Lu Q. Chronic urticaria: advances in understanding of the disease and clinical management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;1–25.

Dabas G, Thakur V, Bishnoi A, Parsad D, Kumar A, Kumaran MS. Causal relationship between D-dimers and disease status in chronic spontaneous urticaria and adjuvant effect of oral tranexamic acid. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12(5):726.

Ghazanfar MN, Thomsen SF. D-dimer as a potential blood biomarker for disease activity and treatment response in chronic urticaria: a focused review. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28:731–5.

Zuberbier T, Bernstein JA, Maurer M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria guidelines: what is new? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1249–55.

Jáuregui I, et al. Antihistamines in the treatment of chronic urticaria. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2007;17(Suppl 2):41–52.

Guillen-Aguinaga S, Jáuregui Presa I, Aguinaga-Ontoso E, Guillen-Grima F, Ferrer M. Updosing nonsedating antihistamines in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(6):1153–65.

Podder I, Dhabal A, Chakraborty SS. Efficacy and safety of up-dosed second-generation antihistamines in uncontrolled chronic spontaneous urticaria: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(3):44–50.

Gabrielli S, et al. Chronic urticaria in children can be controlled effectively with updosing second-generation antihistamines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):1535–7.

Novák Z, et al. Safety and tolerability of bilastine 10 mg administered for 12 weeks in children with allergic diseases. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(5):493–8.

Potter P, et al. Rupatadine is effective in the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria in children aged 2–11 years. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(1):55–61.

Hon KL, Leung AK, Ng WG, Loo SK. Chronic urticaria: an overview of treatment and recent patents. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2019;13(1):27–37.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Akenroye AT, McEwan C, Saini SS. Montelukast reduces symptom severity and frequency in patients with angioedema-predominant chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(4):1403–5.

Zhao Z-T, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(6):1742-1750.e4.

Urgert MC, van den Elzen MT, Knulst AC, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ. Omalizumab in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review and GRADE assessment. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(2):404–15.

Maurer M, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic urticaria who exhibit IgE against thyroperoxidase. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):202-209.e5.

Metz M, Vadasz Z, Kocatürk E, Giménez-Arnau AM. Omalizumab updosing in chronic spontaneous urticaria: an overview of real-world evidence. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;59(1):38–45.

Licari A, et al. Biologic drugs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Acta Bio-medica Atenei Parmensis. 2021;92(S7):e2021527–e2021527.

Lieberman PL, Jones I, Rajwanshi R, Rosén K, Umetsu DT. Anaphylaxis associated with omalizumab administration: risk factors and patient characteristics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(6):1734-1736.e4.

Murphy KR, Winders T, Smith B, Millette L, Chipps BE. Identifying patients for self-administration of omalizumab. Adv Ther. 2023;40(1):19–24.

Kulthanan K, et al. Cyclosporine for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):586–99.

Savic S, et al. Retrospective case note review of chronic spontaneous urticaria outcomes and adverse effects in patients treated with omalizumab or ciclosporin in UK secondary care. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2015;11:1–11.

CAS Google Scholar

Endo T, et al. Identification of biomarkers for predicting the response to cyclosporine A therapy in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergol Int. 2019;68(2):270–3.

Sharma VK, Singh S, Ramam M, Kumawat M, Kumar R. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind pilot study of methotrexate in the treatment of H1 antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80(2):122–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.129382 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Leducq S, et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate versus placebo as add-on therapy to H1 antihistamines for patients with difficult-to-treat chronic spontaneous urticaria: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):240–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.097 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Patil AD, Bingewar G, Goldust M. Efficacy of methotrexate as add on therapy to H1 antihistamine in difficult to treat chronic urticaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e14077. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14077 .

Tal Y, Toker O, Agmon-Levin N, Shalit M. Azathioprine as a therapeutic alternative for refractory chronic urticaria. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(3):367–9.

Pathania YS, Bishnoi A, Parsad D, Kumar A, Kumaran MS. Comparing azathioprine with cyclosporine in the treatment of antihistamine refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: a randomized prospective active-controlled non-inferiority study. World Allergy Organ J. 2019;12(5): 100033.

Zimmerman AB, Berger EM, Elmariah SB, Soter NA. The use of mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of autoimmune and chronic idiopathic urticaria: experience in 19 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(5):767–70.

Shahar E, Bergman R, Guttman-Yassky E, Pollack S. Treatment of severe chronic idiopathic urticaria with oral mycophenolate mofetil in patients not responding to antihistamines and/or corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(10):1224–7.

Cassano N, D’Argento V, Filotico R, Vena GA. Low-dose dapsone in chronic idiopathic urticaria: preliminary results of an open study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;1(1):1–1.

Google Scholar

Noda S, Asano Y, Sato S. Long-term complete resolution of severe chronic idiopathic urticaria after dapsone treatment. J Dermatol. 2012;39(5):496–7.

Morgan M, Cooke A, Rogers L, Adams-Huet B, Khan DA. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of dapsone in antihistamine refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(5):601–6.

Liang SE, Hoffmann R, Peterson E, Soter NA. Use of dapsone in the treatment of chronic idiopathic and autoimmune urticaria. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(1):90–5.

Watanabe J, Shimamoto J, Kotani K. The effects of antibiotics for Helicobacter pylori eradication or dapsone on chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiotics. 2021;10(2):156.

Boonpiyathad T, Sangasapaviliya A. Hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of anti-histamine refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria, randomized single-blinded placebo-controlled trial and an open label comparison study. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;49(5):220–4.

Reeves G, Boyle M, Bonfield J, Dobson P, Loewenthal M. Impact of hydroxychloroquine therapy on chronic urticaria: chronic autoimmune urticaria study and evaluation. Intern Med J. 2004;34(4):182–6.

Khan N, Epstein TG, DuBuske I, Strobel M, Bernstein DI. Effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine and omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a real-world study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(12):3300–5.

Mitzel-Kaoukhov H, Staubach P, Müller-Brenne T. Effect of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in therapy-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104(3):253–8.

Odonnell B, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(1):101–6.

Pereira C, et al. Low-dose intravenous gammaglobulin in the treatment of severe autoimmune urticaria. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;39(7):237–42.

Yu L, et al. Immunological effects and potential mechanisms of action of autologous serum therapy in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(9):1747–54.

Majid I, Shah S, Hassan A, Aleem S, Aziz K. How effective is autologous serum therapy in chronic autoimmune urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(1):102.

Godse KV, Nadkarni N, Patil S, Mehta A. Subcutaneous autologous serum therapy in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62(5):505.

Datta A, Chandra S, Saha A, Sil A, Das NK. Exploring the safety and effectiveness of subcutaneous autologous serum therapy versus conventional intramuscular autologous serum therapy in chronic urticaria: an observer-blind, randomized, controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:632.

Abadeh A, Lee JK. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with dupilumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221117702.

Maurer M, et al. Dupilumab significantly reduces itch and hives in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: results from a phase 3 trial (LIBERTY-CSU CUPID Study A). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(2):AB312.

Kolkhir P, Altrichter S, Munoz M, Hawro T, Maurer M. New treatments for chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(1):2–12.

Chakravarty SD, Yee AF, Paget SA. Rituximab successfully treats refractory chronic autoimmune urticaria caused by IgE receptor autoantibodies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(6):1354–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.023 .

Arkwright PD. Anti-CD20 or anti-IgE therapy for severe chronic autoimmune urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(2):510–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.043 . ( author reply 511 ).

Combalia A, Losno RA, Prieto-Gonzalez S, Mascaro JM. Rituximab in refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: an encouraging therapeutic approach. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2018;31(4):184–7. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487402 .

Piconi S, et al. Immune profiles of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;128(1):59–66. https://doi.org/10.1159/000058004 .

Hermes B, Prochazka AK, Haas N, Jurgovsky K, Sticherling M, Henz BM. Upregulation of TNF-alpha and IL-3 expression in lesional and uninvolved skin in different types of urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(2 Pt 1):307–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70506-3 .

Sharma P, Sharma PK, Chitkara A, Rani S. To evaluate the role and relevance of cytokines IL-17, IL-18, IL-23 and TNF-alpha and their correlation with disease severity in chronic urticaria. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11(4):594–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_396_19 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Off-label use of TNF-alpha inhibitors in a dermatological university department: retrospective evaluation of 118 patients. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28(3):158–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12222 .

Wilson LH, Eliason MJ, Leiferman KM, Hull CM, Powell DL. Treatment of refractory chronic urticaria with tumor necrosis factor-alfa inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(6):1221–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.043 .

Atwa M, Emara A, Youssef N, Bayoumy N. Serum concentration of IL-17, IL-23 and TNF-α among patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: association with disease activity and autologous serum skin test. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(4):469–74.

Lin W, Zhou Q, Liu C, Ying M, Xu S. Increased plasma IL-17, IL-31, and IL-33 levels in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17797.

Sabag D, et al. Interleukin-17 is a potential player and treatment target in severe chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50(7):799–804.

Arm JP, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of QGE 031 (ligelizumab), a novel high-affinity anti-IgE antibody, in atopic subjects. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44(11):1371–85.

Maurer M, et al. Ligelizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(14):1321–32.

Maurer M, et al. Sustained safety and efficacy of ligelizumab in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a one-year extension study. Allergy. 2022;77(7):2175–84.

Kuo B-S, et al. IgE-neutralizing UB-221 mAb, distinct from omalizumab and ligelizumab, exhibits CD23-mediated IgE downregulation and relieves urticaria symptoms. J Clin Investig. 2022;132(15): e157765.

Metz M, et al. Fenebrutinib in H1 antihistamine-refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(11):1961–9.

Maurer M, et al. Remibrutinib, a novel BTK inhibitor, demonstrates promising efficacy and safety in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1498-1506.e2.

Maurer M, et al. Remibrutinib treatment improves quality of life in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(2):AB179.

Kay A, et al. Elevations in vascular markers and eosinophils in chronic spontaneous urticarial weals with low-level persistence in uninvolved skin. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(3):505–11.

Altrichter S, et al. The role of eosinophils in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(6):1510–6.

Magerl M, et al. Benefit of mepolizumab treatment in a patient with chronic spontaneous urticaria. JDDG Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. 2018;16(4):477–8.

Maurer M, Altrichter S, Metz M, Zuberbier T, Church M, Bergmann K. Benefit from reslizumab treatment in a patient with chronic spontaneous urticaria and cold urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 2017;32(3):e112–3.

Bernstein JA, Singh U, Rao MB, Berendts K, Zhang X, Mutasim D. Benralizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1389–91.

Kay A, Clark P, Maurer M, Ying S. Elevations in T-helper-2-initiating cytokines (interleukin-33, interleukin-25 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin) in lesional skin from chronic spontaneous (‘idiopathic’) urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(5):1294–302.

Johal KJ, Saini SS. Current and emerging treatments for chronic spontaneous urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125(4):380–7.

Altrichter S, et al. An open-label, proof-of-concept study of lirentelimab for antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous and inducible urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(5):1683-1690.e7.

Yahara H, Satoh T, Miyagishi C, Yokozeki H. Increased expression of CRTH2 on eosinophils in allergic skin diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 2009;24(1):75–6.

Oliver ET, Sterba PM, Devine K, Vonakis BM, Saini SS. Altered expression of chemoattractant receptor–homologous molecule expressed on TH2 cells on blood basophils and eosinophils in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(1):304-306.e1.

Oliver ET, et al. Effects of an oral CRTh2 antagonist (AZD1981) on eosinophil activity and symptoms in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;179(1):21–30.

Alvarado D, et al. Anti-KIT monoclonal antibody CDX-0159 induces profound and durable mast cell suppression in a healthy volunteer study. Allergy. 2022;77(8):2393–403.

Maurer M, et al. Safety and clinical activity of multiple doses of barzolvolimab, an anti-KIT antibody, in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;151(2):AB133.

Ramirez Molina C, Falkencrone S, Skov PS, Hooper-Greenhill E, Barker M, Dickson MC. GSK2646264, a spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor, attenuates the release of histamine in ex vivo human skin. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(8):1135–42.

Dickson MC, et al. Effects of a topical treatment with spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor in healthy subjects and patients with cold urticaria or chronic spontaneous urticaria: results of a phase 1a/b randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(12):4797–808.

Download references

Acknowledgements

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

No medical writing or editorial assistance was used for this article.

Author Contributions

Georgia Biazus Soares- writing and editing of the manuscript, creation of the figure; Omar Mahmoud- writing of the manuscript; Gil Yosipovitch- concept design, reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Georgia Biazus Soares and Omar Mahmoud have nothing to disclose. Dr. Gil Yosipovitch serves as an advisory board member for Abbvie, Arcutis, BMS, Cara Therapuetics, GSK. Escient Health, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi, TreviTherapeutics, and Vifor; Dr. Gil Yosipovitch receives grants/research funding from Eli Lilly, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Galderma, Escient, Sanofi Regeneron, and Celldex; Dr. Gil Yosipovitch Received Pathways grants as Investigator for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Sanofi.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dr. Phillip Frost Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, Miami Itch Center, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 5555 Ponce de Leon, Coral Gables, FL, 33146, USA

Gil Yosipovitch, Georgia Biazus Soares & Omar Mahmoud

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gil Yosipovitch .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yosipovitch, G., Biazus Soares, G. & Mahmoud, O. Current and Emerging Therapies for Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Narrative Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13 , 1647–1660 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00972-6

Download citation

Received : 15 May 2023

Accepted : 20 June 2023

Published : 29 June 2023

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00972-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Chronic spontaneous urticaria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- BAD Guidelines

- Cover Archive

- Plain Language Summaries

- Supplements

- Trending Articles

- Virtual Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Reasons to Publish

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About British Journal of Dermatology

- About British Association of Dermatologists

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Purpose and scope, methodology, summary of recommendations, appropriate investigations, interventions, considerations, recommended audit points, stakeholder involvement and peer review, limitations of the guideline, plans for guideline revision, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with chronic urticaria 2021 *

The author affiliations can be found in the Appendix.

Conflicts of interest The following interests were declared over the duration of the guideline development. C.E.H.G.: honoraria and research investigator – Novartis – specific. M.R.A.‐J.: (1) sponsorship to conferences – Allergy Therapeutics, Novartis, Celgene – specific; (2) grant/research support – AbbVie, Emblation, Unilever – nonspecific. A.B.: (1) consultant, AbbVie, Almirall, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Galderma, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, UCB – specific. C.F.: sponsorship to attend a conference – Novartis – specific; (2) travel grants from LEO Pharma, Almirall, Novartis – specific; (3) investigator‐initiated studies from Janssen and LEO Pharma – nonspecific. T.A.L.: advisory board – Galderma, La Roche‐Posay, Novartis – specific. A.M.M.: (1) consultant and advisory board – Novartis – specific; (2) invited speaker – Novartis – specific. G.O.: advisory board – Novartis – specific. R.A.S., F.L., L.C., W.A.C.S., M.H. L.S.E., M.F.M.M. and M.C.E. declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Produced in 2001 by the British Association of Dermatologists. Reviewed and updated 2010, 2021

This is an updated guideline prepared for the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) Clinical Standards Unit, which includes the Therapy & Guidelines Subcommittee (T&G). Members of the Clinical Standards Unit who have been involved are N.J. Levell (Chair, T&G), S.L. Chua, P. Laws, H. Frow, A. Bardhan, A. Daunton, G. Petrof, M. Hashme (BAD Information Scientist), L.S. Exton (BAD Senior Guideline Research Fellow), M.C. Ezejimofor (BAD Guideline Research Fellow) and M.F. Mohd Mustapa (BAD Director of Clinical Standards).

NICE has renewed accreditation of the process used by the British Association of Dermatologists to produce clinical guidelines. The renewed accreditation is valid until 31 May 2026 and applies to guidance produced using the processes described in the updated guidance for writing a British Association of Dermatologists clinical guideline – the adoption of the GRADE methodology 2016. The original accreditation term began on 12 May 2010. More information on accreditation can be viewed at www.nice.org.uk/accreditation .

* Plain language summary available online

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

R.A. Sabroe, F. Lawlor, C.E.H. Grattan, M.R. Ardern‐Jones, A. Bewley, L. Campbell, C. Flohr, T.A. Leslie, A.M. Marsland, G. Ogg, W.A.C. Sewell, M. Hashme, L.S. Exton, M.F. Mohd Mustapa, M.C. Ezejimofor, on behalf of the British Association of Dermatologists’ Clinical Standards Unit, British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with chronic urticaria 2021, British Journal of Dermatology , Volume 186, Issue 3, 1 March 2022, Pages 398–413, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20892

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Plain language summary available online

offer an appraisal of all relevant literature up to March 2020, focusing on any key developments,

address important, practical clinical questions relating to the primary guideline objective, and

provide guideline recommendations and if appropriate research recommendations.

The guideline is presented as a detailed review with highlighted recommendations for practical use in primary, secondary and tertiary care, in addition to an updated patient information leaflet (PIL; available on the BAD Skin Health Information website, https://www.skinhealthinfo.org.uk/a‐z‐conditions‐treatments ).

Other than providing background information, the guideline does not cover angio‐oedema without weals [other than idiopathic, which is now classified as part of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU)], hereditary angio‐oedema, autoinflammatory syndromes or differential diagnosis. Additionally, the guideline focuses on chronic rather than acute urticaria.

This set of guidelines has been developed using the BAD’s recommended methodology. 1 Further information can be found in Appendix J (see Supporting Information) with reference to the AGREE II instrument ( www.agreetrust.org ) 2 and GRADE. 3 The recommendations were developed for implementation in the UK National Health Service (NHS).

The Guideline Development Group (GDG), which consisted of eight consultant dermatologists managing adults, children and young people; a consultant immunologist; a consultant psychodermatologist; a drug allergy specialist; two patient representatives and a technical team (consisting of an information scientist, guideline research fellows and a project manager providing methodological and technical support), established a number of clinical questions pertinent to the scope of the guideline and two sets of outcome measures of importance to patients, ranked according to the GRADE methodology (section 2.1; and Appendix A ; see Supporting Information).

A systematic literature search of the PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane databases was conducted to identify key articles on urticaria from January 2007 to March 2020. An additional, targeted literature search for the antihistamines acrivastine and bilastine was also carried out (from January 1980 to March 2020). Subsequently published papers known to the GDG were included. The final literature searches were run ahead of journal submission in 2021 to ensure currency. The search terms and strategies are detailed in Appendix K (see Supporting Information). Additional references relevant to the topic were also isolated from citations in the reviewed literature and the previous version of the guideline. 4 Evidence from the included studies was graded according to the GRADE system (high, moderate, low or very low certainty).

The recommendations are based on evidence drawn from systematic reviews of the literature pertaining to the clinical questions identified, following discussions with the entire GDG and factoring in all four factors that would affect their strength rating according to the GRADE approach (i.e. balance between desirable and undesirable effects, quality of evidence, patient values and preferences, and resource allocation). All GDG members contributed towards drafting and/or reviewing the narratives and information in the guideline and Supporting Information documents. When there was insufficient evidence from the literature, informal consensus was reached based on the experience of medical and patient GDG members.

The summary of findings with forest plots (Appendix B ), tables Linking the Evidence To the Recommendations (LETR; Appendix C ), GRADE evidence profiles indicating the quality of evidence (Appendix D ), summary of included studies (Appendix E ), narrative findings for noncomparative studies (Appendix F ), PRISMA flow diagram (Appendix G ), list of excluded studies (Appendix H ) and AMSTAR 2 appraisal of the included systematic reviews (Appendix I ) are detailed in the Supporting Information.

The strength of recommendation is expressed by the wording and symbols shown in Table 1 .

Strength of recommendation ratings

| Strength | Wording | Symbol | Definition |

| Strong recommendation the use of an intervention | ‘Offer’ (or similar, e.g. ‘use’, ‘provide’, ‘take’, ‘investigate’ etc.) | ↑↑ | Benefits of the intervention outweigh the risks; most patients would choose the intervention whilst only a small proportion would not; for clinicians, most of their patients would receive the intervention; for policymakers, it would be a useful performance indicator |

| Weak recommendation the use of an intervention | ‘Consider’ | ↑ | Risks and benefits of the intervention are finely balanced; most patients would choose the intervention but many would not; clinicians would need to consider the pros and cons for the patient in the context of the evidence; for policymakers it would be a poor performance indicator where variability in practice is expected |

| No recommendation | Θ | Insufficient evidence to support any recommendation | |

| Strong recommendation the use of an intervention | ‘Do not offer’ | ↓↓ | Risks of the intervention outweigh the benefits; most patients would choose the intervention whilst only a small proportion would; for clinicians, most of their patients would receive the intervention |

| Strength | Wording | Symbol | Definition |

| Strong recommendation the use of an intervention | ‘Offer’ (or similar, e.g. ‘use’, ‘provide’, ‘take’, ‘investigate’ etc.) | ↑↑ | Benefits of the intervention outweigh the risks; most patients would choose the intervention whilst only a small proportion would not; for clinicians, most of their patients would receive the intervention; for policymakers, it would be a useful performance indicator |

| Weak recommendation the use of an intervention | ‘Consider’ | ↑ | Risks and benefits of the intervention are finely balanced; most patients would choose the intervention but many would not; clinicians would need to consider the pros and cons for the patient in the context of the evidence; for policymakers it would be a poor performance indicator where variability in practice is expected |

| No recommendation | Θ | Insufficient evidence to support any recommendation | |

| Strong recommendation the use of an intervention | ‘Do not offer’ | ↓↓ | Risks of the intervention outweigh the benefits; most patients would choose the intervention whilst only a small proportion would; for clinicians, most of their patients would receive the intervention |

Clinical questions and outcomes

The GDG established the following clinical questions pertinent to the scope of the guideline.

Review question 1: investigation

Do tests, such as blood tests and the autologous serum skin test, alter the management of urticaria?

Review question 2: treatment

What is the clinical effectiveness of any H 1 ‐antihistamine compared with another for the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 3: treatment

Would changing from one H 1 ‐antihistamine to another lead to benefit in the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 4: treatment

Would adding an H 2 ‐antihistamine to an H 1 ‐antihistamine lead to benefit in the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 5: treatment

What is the effectiveness of leukotriene receptor antagonists in the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 6: treatment

What are the effectiveness and safety of increasing doses of H 1 ‐antihistamines?

Review question 7: treatment

Would adding other therapies to an H 1 ‐antihistamine lead to benefit in the treatment of urticaria, including sulfasalazine, dapsone, thyroxine, tricyclic antidepressants, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, danazol, tranexamic acid, mycophenolate mofetil, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) and anticoagulants?

Review question 8: treatment

What is the effectiveness of taking systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 9: treatment

What is the effectiveness of dietary exclusions or supplements for the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 10: treatment

What is the effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori eradication for the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 11: treatment

What is the effectiveness of avoiding nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 12: treatment

What is the effectiveness of ciclosporin for the treatment of urticaria and are there any long‐term benefits?

Review question 13: treatment

What is the effectiveness of omalizumab for the treatment of urticaria?

Review question 14: treatment

Is the response to treatment for inducible urticarias (e.g. symptomatic dermographism, delayed pressure urticaria, cold urticaria, cholinergic urticaria, vibratory angio‐oedema, localized heat urticaria) the same as for CSU?

Review question 15: treatment

Do any other specific interventions work for inducible urticarias, such as antibiotics in cold urticaria, sulfasalazine in delayed pressure urticaria, phototherapy in dermographism, plasmapheresis in solar urticaria and anticholinergics in cholinergic urticaria?

Review question 16: treatment

Which H 1 ‐antihistamines can be used in pregnancy?

Review question 17: treatment

Which H 1 ‐antihistamines can be used during breastfeeding?

Review question 18: treatment

What are the key differences in the diagnosis and management of paediatric compared with adult urticaria (if there are any)?

Review question 19: treatment

What is the clinical effectiveness of miscellaneous monotherapies compared with each other for the treatment of urticaria?

The GDG also established two sets of outcome measures of importance to patients (for treatment and investigation), ranked according to the GRADE methodology, 5 by the patient representatives (for the full review protocol see Appendix A in the Supporting Information). In the investigation protocol, the outcome is either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The treatment outcomes (Table 2 ) use a nine‐point scale; outcomes ranked 9, 8 or 7 are critical for decision making; those ranked 6, 5 or 4 are important but not critical for decision making; and those ranked 3, 2 or 1 are the least important for decision making.

Outcome measures and ranking

| Disease control | 9 |

| Decrease in urticarial activity | 9 |

| Adverse effects | 9 |

| Quality of life | 9 |

| Time to clinical effect | 7 |

| Relapse | 6 |

| When to stop treatment | 3 |

| Disease control | 9 |

| Decrease in urticarial activity | 9 |

| Adverse effects | 9 |

| Quality of life | 9 |

| Time to clinical effect | 7 |

| Relapse | 6 |

| When to stop treatment | 3 |

The following recommendations and ratings were agreed upon unanimously by members of the GDG and patient representatives.

For further information on the wording used for recommendations and strength of recommendation ratings see Table 1 . The evidence on which the recommendations are based is featured and discussed in Appendices B–E (see Supporting Information). The GDG is aware of the lack of high‐quality evidence for many of these recommendations, therefore, strong recommendations with an asterisk (*) are based on available evidence, as well as informal consensus and specialist experience of medical and patient GDG members. Good practice point (GPP) recommendations are derived from informal consensus.

the recommendations are based on expert opinion as there is very little published evidence

there are additional notes in section 9.1 and Table 3 .

First‐line antihistamines for chronic urticaria in children

| Drug | 1 month to 1 year | 1–2 years | 2–5 years | 6–11 years | 12–17 years | |

| 1 mg twice a day | x | x | x | x | ||

| 2 mg/5 mL oral solution | ||||||

| x | Unlicensed: 250 micrograms per kg twice a day (typically doses up to 2·5 mg twice a day) | 2·5 mg twice a day | 5 mg twice a day | 10 mg daily | ||

| 5 mg/5 mL oral solution | ||||||

| 10 mg tablets | ||||||

| x | 1·25 mg daily | 1·25 mg daily | 2·5 mg daily | 5 mg daily | ||

| 2·5 mg/5 mL oral solution | ||||||

| 5 mg tablets | ||||||

| x | x | < 31 kg: 5 mg daily | < 31 kg: 5 mg daily | > 31 kg: 10 mg daily | 10 mg daily | |

| 5 mg/5 mL oral solution | ||||||

| 10 mg tablets | ||||||

| x | x | x | Unlicensed: 30 mg twice daily | 180 mg daily | ||

| 30 mg/120 mg/180 mg tablets | ||||||

| Drug | 1 month to 1 year | 1–2 years | 2–5 years | 6–11 years | 12–17 years | |

| 1 mg twice a day | x | x | x | x | ||

| 2 mg/5 mL oral solution | ||||||

| x | Unlicensed: 250 micrograms per kg twice a day (typically doses up to 2·5 mg twice a day) | 2·5 mg twice a day | 5 mg twice a day | 10 mg daily | ||

| 5 mg/5 mL oral solution | ||||||

| 10 mg tablets | ||||||

| x | 1·25 mg daily | 1·25 mg daily | 2·5 mg daily | 5 mg daily | ||

| 2·5 mg/5 mL oral solution | ||||||

| 5 mg tablets | ||||||

| x | x | < 31 kg: 5 mg daily | < 31 kg: 5 mg daily | > 31 kg: 10 mg daily | 10 mg daily | |

| 5 mg/5 mL oral solution | ||||||

| 10 mg tablets | ||||||

| x | x | x | Unlicensed: 30 mg twice daily | 180 mg daily | ||

| 30 mg/120 mg/180 mg tablets | ||||||

Table 3 summarizes the antihistamines commonly used in the UK. Chlorphenamine is a sedating antihistamine and thus daytime drowsiness and reduced attention, visual memory and learning are very common. It also causes abnormal sleep at night with delayed and reduced REM sleep. For these reasons, it should be used with caution, particularly over longer periods. It is not recommended for use beyond 1 year when alternative low‐sedating antihistamines are available. Cetirizine can cause drowsiness, especially when used above the licensed dose. Hence it is to be used with caution in school‐aged children. However, if the child has been started on cetirizine with benefit, then this therapy can be continued. Loratadine and desloratadine may be less effective than cetirizine, but are less likely to cause drowsiness. Like chlorphenamine, they are metabolized in the liver, increasing the risks of drug accumulation and drug interactions. Fexofenadine is licensed for seasonal allergic rhinitis from the age of 6 years, and for urticaria from the age of 12 years. It can be considered for unlicensed use for urticaria from the age of 6 years. For all children with chronic urticaria who have an inadequate response to standard doses, the frequency of administration of nonsedating antihistamines can be increased up to a maximum of four times a day.

Licensing information, dosages and monitoring requirements for specific drugs are not included. However, of note, apart from H 1 ‐antihistamines, oral steroids and omalizumab, none of the other treatment options discussed are licensed in the UK for use in urticaria. Except where otherwise stated, we recommend adherence to published guidelines, for example by the manufacturer, the BAD or, in the UK, the British National Formulary ( www.bnf.org ). In particular, note the licensed dosages for people aged < 14 years (also see Table 3 ).

The recommendations relate to chronic spontaneous and inducible urticarias. Acute urticaria, angio‐oedema without weals (other than idiopathic, which is now classified as part of CSU), hereditary angio‐oedema and autoinflammatory diseases are not covered.

For clarity, we have divided the management options into sections (general treatment, first‐, second‐ and third‐line options). However, depending on disease severity, disease fluctuation, comorbidities and the national criteria for use of drugs, the order and combinations of treatment may vary and may change during the course of each person’s disease.

We note that, since submission of this article for publication, a new international guideline on the management of urticaria has been published. 6 Broadly, the recommendations are similar, except that the international guideline favours omalizumab over ciclosporin for CSU.

General management for people with all types of chronic urticaria

The most important step is to take a detailed clinical history, with examination supplemented by people’s own photographs. In most cases this will provide an accurate clinical diagnosis (section 5.2), which will guide management. Disease pathogenesis may also be important in management (section 5.3).

R1 (↑) Only consider baseline investigations if clinically indicated (see section 6.0).

R2 (GPP) Consider using appropriate validated scoring systems to assess disease activity and impact, for example Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), weekly Urticaria Activity Score 7 (UAS7), Angioedema Activity Score (AAS) and/or Urticaria Control Test (UCT).

R3 (GPP) Provide educational material or a patient information leaflet on urticaria or angio‐oedema ( https://www.skinhealthinfo.org.uk/a‐z‐conditions‐treatments ).

R4 (GPP) Offer access to support and treatment for anxiety, depression and the psychosocial impact of the disease, where appropriate. The psychological impact can be assessed using, for example, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

R5 (GPP) Consider topical antipruritic agents, such as a menthol‐containing emollient.

R6 (GPP) Advise avoidance of identified triggers or exacerbating factors, such as drugs, and in particular triggers for inducible urticarias.

R7 (↑↑) Stop angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in people with angio‐oedema without weals.

General management for people with chronic spontaneous urticaria

R8 (↑↑) Avoid NSAIDs in people whose CSU appears to be exacerbated by this class of drugs.

R9 (↑) Consider switching NSAID treatment to a selective cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor, if tolerated and not contraindicated, when there is a history of acute exacerbation of CSU after NSAID intake for inflammation. However, evidence of benefit from switching low‐dose aspirin when taken as an antithrombotic to an alternative antiplatelet drug is lacking. Refer to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 7 British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) 8 or European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) guidance 9 if reactivity to NSAIDs is suspected.

R10 (GPP) Do not advise dietary exclusion routinely. If, from a detailed history, food appears to play a role, investigate appropriately.

Θ1 There is insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening for vitamin D deficiency.

Θ2 There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation on dietary supplementation.

R11 (↓↓) Do not offer routine screening for Helicobacter pylori .

First‐line treatment options for people with chronic spontaneous urticaria

R12 (↑↑) Offer a second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamine, using a regular daily licensed dose (Table 4 ).

Examples of first‐ and second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamines

| Licensed oral dose for adults (see Table for children) | |

| Chlorphenamine | 4 mg every 4–6 h, maximum 24 mg per day (elderly maximum 12 mg per day) |

| Cyproheptadine | 4 mg three times per day (maximum 32 mg per day) |

| Hydroxyzine | Initially 10–25 mg at night, maximum 25 mg three to four times per day (elderly maximum 25 mg twice daily) |

| Promethazine | 10–20 mg two to three times per day |

| Acrivastine | 8 mg three times a day |

| Cetirizine | 10 mg once daily |

| Desloratadine | 5 mg once daily |

| Fexofenadine | 180 mg once daily |

| Loratadine | 10 mg once daily |

| Levocetirizine | 5 mg once daily |

| Mizolastine | 10 mg once daily |

| Licensed oral dose for adults (see Table for children) | |

| Chlorphenamine | 4 mg every 4–6 h, maximum 24 mg per day (elderly maximum 12 mg per day) |

| Cyproheptadine | 4 mg three times per day (maximum 32 mg per day) |

| Hydroxyzine | Initially 10–25 mg at night, maximum 25 mg three to four times per day (elderly maximum 25 mg twice daily) |

| Promethazine | 10–20 mg two to three times per day |

| Acrivastine | 8 mg three times a day |

| Cetirizine | 10 mg once daily |

| Desloratadine | 5 mg once daily |

| Fexofenadine | 180 mg once daily |

| Loratadine | 10 mg once daily |

| Levocetirizine | 5 mg once daily |

| Mizolastine | 10 mg once daily |

a From the British National Formulary.

R13 (↓↓) Do not offer first‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamines routinely, unless there is no alternative, due to concerns about their short‐ and long‐term effects on the central nervous system.

R14 (↑↑) Offer updosing (i.e. increasing the dose above the licensed dose) of a single second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamine, by up to fourfold the licensed dose, to people whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by the standard licensed dose, provided it is tolerated and there is no caution or contraindication (see section 7.2 and Appendix C – LETR narratives). Attempt stepwise dose reduction following complete symptom control. There is no evidence to guide the optimum duration of updosing or speed of dose reduction.

R15 (↓↓) Do not updose mizolastine (see section 7.2).

R16 (GPP) Consider switching from one second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamine to another in people whose symptoms do not respond adequately to, or who do not tolerate, the first drug at standard or increased doses.

Θ3 There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation on using two different second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamines at the same time.

R17 (↓↓) Do not updose first‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamines (see R13).

R18 (↑) Consider montelukast, in addition to a second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamine, in people whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by standard and increased doses of second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamines.

R19 (↑↑) Offer* progression of therapy, through first‐line treatment options (see R12–R18) every 2–4 weeks (every 2 weeks in severe treatment‐resistant disease).

Θ4 There is insufficient evidence to recommend routine addition of H 2 ‐antihistamines to second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamines for people whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by the latter. However, they may be considered if urticaria is associated with dyspepsia, although dyspepsia should be investigated appropriately. See section 7.4.

R20 (↑) Consider oral prednisolone (e.g. 0·5 mg kg −1 ) for short, infrequent courses of a few days as rescue treatment to control severe exacerbations, in addition to continued use of a second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamine.

R21 (↓↓) Do not offer* long‐term systemic corticosteroids unless there is no other option. Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible period. 10

Second‐line treatment options for people with chronic spontaneous urticaria

For people with CSU with an inadequate response to first‐line treatment, the following additional investigations may be relevant when considering the next treatment options.

R22 (↓↓) Do not offer autologous serum skin tests (ASSTs) or autologous plasma skin tests (APSTs) routinely.

R23 (↑) Consider measuring total IgE levels: a high total IgE level may indicate a higher probability of early disease responsiveness to omalizumab, whereas a normal total IgE level may indicate disease responsiveness to ciclosporin (section 6 and Appendix C – LETR narratives).

R24 (↑) If available, consider a basophil histamine release assay (BHRA), although it is not yet subject to a national quality assurance scheme. A positive BHRA may indicate a higher probability of disease responsiveness to ciclosporin and slower or delayed response to omalizumab, whereas a negative BHRA may indicate a higher probability of disease responsiveness to omalizumab (section 6 and Appendix C – LETR narratives).

Note: total IgE levels (R23) and BHRAs (R24) are only indicative and may not reflect actual clinical responsiveness in all patients.

R25 (↑↑) Offer omalizumab, in addition to a second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamine, to people whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by first‐line options.

R26 (↑↑) Offer* ciclosporin for 3–6 months, in addition to a second‐generation H 1 ‐antihistamine, to people whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by first‐line options.

R27 (↑↑) Avoid long‐term use of ciclosporin where possible; if not, use at the lowest effective dose, interrupt treatment periodically to confirm continued requirement, and consider alternative agents (see R25, R28 and Θ5).

Third‐line treatment options for people with chronic spontaneous urticaria

azathioprine