Advertisement

How Digital Cinema Works

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

To the audience, the most important aspect of digital cinema is the projection system. This is the final piece of technology that controls how the movie actually looks at the end of the line.

Pretty much everybody agrees that a good film projector loaded with a pristine film print produces a fantastic, vibrant picture. The problem is, every time you play the movie, the film quality drops a little. When you go to a movie that's been playing for a few weeks, you'll probably see hundreds of scratches and bits of dirt.

Many critics hold that a projected digital movie is inferior to a pristine film print, but they recognize that while a film print gradually degrades, a digital movie looks the same every time you show it. Think of a CD as compared to an audio tape. Every time you play an audio tape, the sound gets a little warped. A CD's digital information sounds exactly the same every time you listen to it (unless it gets scratched).

Today, there are two major digital cinema projector technologies: Micromirror projectors and LCD projectors.

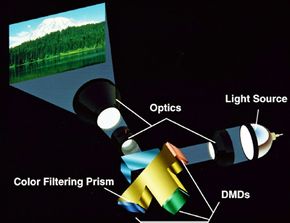

Micromirror projectors , like Texas Instruments' Digital Light Processing (DLP) line, form images with an array of microscopic mirrors . In this system, a high-power lamp shines light through a prism . The prism splits the light into the component colors red, green and blue. Each color beam hits a different Digital Micromirror Device (DMD) -- a semiconductor chip that is covered in more than a million hinged mirrors.

Based on the information encoded in the video signal, the DMD turns over the tiny mirrors to reflect the colored light. Collectively, the tiny dots of reflected light form a monochromatic image. To see how this works, imagine a crowd of people on the ground at night, each holding a square-foot mirror. A helicopter flies overhead and shines a light down on the crowd. Depending on which people held their mirrors up, you would see a different reflected image. If everybody worked together, they could spell out words or form images. If you had more than a million people, pressed shoulder to shoulder, you could make highly detailed pictures.

In actuality, most of the individual mirrors are flipped from "on" (reflecting light) to "off" (not reflecting light) and back again thousands of times per second. A mirror that is flipped on a greater proportion of the time will reflect more light and so will form a brighter pixel than a mirror that is not flipped on for as long. This is how the DMD creates a gradation between light and dark. The mirrors that are flipping rapidly from on to off create varying shades of gray (or varying shades of red, green and blue, in this case).

Each micromirror chip reflects the monochromatic image back to the prism, which recombines the colors. The red, green and blue rejoin to form a full color image, which is projected on the screen.

LCD projectors , such as JVC's Digital Image Light Amplifier (D-ILA) line, work on a slightly different system. These projectors reflect high-intensity light off of a stationary mirror covered with a liquid crystal display (LCD). Based on the digital signal, the projector directs some of the liquid crystals to let reflected light through and others to block it. In this way, the LCD modifies the high-intensity light beam to create an image.

There is a flip-side to digital projector technology. In both projector designs, individual pixels may break from time to time. When this happens, it degrades the image quality of every single movie shown on that projector. In contrast, if a film print gets scratched, it's only that particular movie that's damaged -- the next print looks fine.

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Step inside a movie projection booth to see what's changed since film

Bob Mondello

Before digital projectors in movie theaters, projectionists had to quickly move from one film reel to the next. NPR looks at what has changed since the days of film in our series, "Backstage Pass."

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

Before he became a film critic, NPR's Bob Mondello worked for a chain of movie theaters. He spent a lot of time in projection booths back then, and it had been a while since Bob climbed those stairs. But on a return visit, the first thing he discovered is that things sound different.

BOB MONDELLO, BYLINE: This is the sound I remember.

(SOUNDBITE OF PROJECTOR PURRING)

MONDELLO: The purr of a celluloid film strip running through a projector, a purr that is actually 24 clicks per second - one each time the shutter closes so that another frame of film can advance. Each frame has to stop briefly in front of the light source, or all you'd see when you look at the screen is a blur. This is how film was first projected by the Lumiere brothers in 1895 and how everyone saw film for the next 104 years. It's been the subject of movies from a silent comedy where Buster Keaton plays a projectionist who dreams himself up onto the screen to the Oscar-winning "Cinema Paradiso," where a little boy falls in love with movies in the projection booth.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "CINEMA PARADISO")

SALVATORE CASCIO: (As Salvatore Di Vita) (Non-English language spoken).

MONDELLO: I could identify. When I was working at Roth Theaters in the 1970s, the sound of the projector starting up seemed to me like an overture at a musical. But it's a sound that mostly doesn't exist anymore at the multiplex. In fact, to record the bit I used at the beginning, I had to ask the American Film Institute to bring projectionist Keith Madden to its Silver Theater from a museum to thread the film and show me how.

KEITH MADDEN: Do you want me to talk and thread at the same time? I can do that. There are sprocket holes on the film that align with sprocket teeth here, and you get them on there. You have to align them perfectly.

MONDELLO: Madden, who is now with the Smithsonian's Museum of African American History and Culture, got his first job as a projectionist in the 1970s, when film was still being played on 20-minute reels. That meant alternating between two side-by-side projectors three times an hour.

MADDEN: If you do it right, you go seamlessly from the last frame of the outgoing reel to the first frame of the incoming reel.

MONDELLO: Doing it right was tricky, though, involving a cue mark on screen and quick reflexes.

MADDEN: You had to just completely get into the Zen of it. You had to stare at the screen. The cue marks were 1/6 of a second in the upper right-hand corner. A sixth of a second is about the time it takes you to do kind of a normal blink. So if you had a normal blink, you could have - oh, did I just miss that? And until you learn the film, you wouldn't know. And one of the worst things for a projectionist was to get emotionally involved in the content. In a horror movie, that used to happen to me. Somebody would jump out with an axe, and, oh, you'd miss the cue mark.

MONDELLO: Later, they developed a platter system, where a whole film could be strung together on one big reel, which was better. But the actual revolution came in 1999, when a few movie theaters started trying out digital projectors. Cinematographer Harris Savides told NPR back then about seeing one work for the first time.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

HARRIS SAVIDES: I felt like we're using horses, and we just saw the first car go by and kind of don't know what it is or what it's going to do for us. But it just seems interesting, better, different.

MONDELLO: That was a minority view at the time. Nobody much liked digital at first. The image wasn't sharp. It was like early TV. Some scenes even looked pixelated. But the projectors got better and smaller. And by 2011, the National Association of Theater Owners estimated that 41% of U.S. movie theaters had converted to digital. Today, it's very close to 100%, says Keith Madden.

MADDEN: Now, if you go to a typical multiplex, in the booth in the back corner of a lot of these places, you'll see piles of rusted metal parts of film projectors.

MONDELLO: Let's go instead to an atypical multiplex - Landmark's eight-screen E Street Theater in downtown Washington, D.C. In what is otherwise a state-of-the-art digital projection booth, it still has one working film projector.

TOM BEDDOW: We barely ever use this anymore. We maybe play two, three 35-millimeter prints a year.

MONDELLO: Tom Beddow, formerly of Landmark Theater, said this while standing in a booth that connects seven of the eight theaters in the complex, a hallway with digital projectors spaced along it and noisy fans blowing the heat away from the powerful xenon bulbs that are needed to light up movie screens the size of tennis courts. The only moving part in a digital projector is the fan. It's otherwise just a light source and a computer.

BEDDOW: Every projector has a little touch-screen interface here. It basically shows the playlist of what you're going to play. It has the ads, the trailers and the film, so all I would have to do to play this film right now is hit the play button. The lights will come down, the sound will turn on, and then at the end of the playlist, the lights come up, it goes back to house music - so literally one button.

MONDELLO: Show me how you thread up one of these digital projectors.

BEDDOW: One of these digital projectors? So we don't thread anything up. We get the movies in these little gray boxes - big, silver hard drives.

MONDELLO: Trailers come on this too?

BEDDOW: Yes. So every week, Deluxe will send what's called a trail mix drive, and...

MONDELLO: In the old days, even with platters, you needed a couple of projectionists to run this place - eight screens, staggered showtimes, cleaning sprocket teeth with a toothbrush between showings, focusing, dealing with bulky projectors.

BEDDOW: It would usually be two full-time projectionists and then two or three part-time projectionists.

MONDELLO: What do you got now?

BEDDOW: (Laughter) We have - everything's automated, so you basically only need to have projectionists there on Thursdays, which is the day that we do the changeover, and everything will start automatically for the whole week.

MONDELLO: For the week?

BEDDOW: Yeah.

MONDELLO: Not every day they have to push a button?

BEDDOW: A manager has to come up here and turn everything on.

MONDELLO: And that would be just as true if this were a 26-plex. Miraculous in its way, the new normal in thousands of theaters around the world is state-of-the-art, efficient, a 21st century technological marvel. So just one more question.

If somebody came up here and wanted to be amazed by something, what would you show them?

BEDDOW: (Laughter) I'd probably thread up the 35-millimeter projector.

MONDELLO: Of course he would.

I'm Bob Mondello.

Copyright © 2023 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- Festival Reports

- Book Reviews

- Great Directors

- Great Actors

- Special Dossiers

- Past Issues

- Support us on Patreon

Subscribe to Senses of Cinema to receive news of our latest cinema journal. Enter your email address below:

- Thank you to our Patrons

- Style Guide

- Advertisers

- Call for Contributions

What Happened? The Digital Shift in Cinema

To understand what the last ten years of cinema have been about, one has to start at the turn of the last century – the year 2000 – when Hollywood decided that it was time to get rid of film itself, and make the shift entirely to digital. With incredible rapidity, 35mm production and projection became obsolete, as did film itself, forcing Eastman Kodak into bankruptcy (from which they have since emerged) – something unthinkable only a decade earlier. Everything about the business changed seemingly overnight. Where before the end product of a feature film was a 35mm print, a poster, a trailer, some lobby cards and the usual press junket for journalists, now films were shot and edited entirely using digital technology, and the theatrical experience began to fall away. Films were no longer located in one place only – movie theatres – then shown much later on television, cut to ribbons and interspersed with commercials. Movies in the 21 st century became available on laptops, cellphones, as streaming video replaced conventional distribution patterns. Movies were now everywhere, all the time, endlessly and effortlessly available.

Needless to say, there was much lost in the shift to digital, which was the most momentous retooling of the cinematic apparatus since the invention of the medium itself. When all movies were shot, edited, and screened in 35mm, theatrical presentation was a necessity, and every film, no matter how high or low the budget, had to open in a theater to make its money back. Thus, exploitation films from American International Pictures shot in 6 days on budgets of $100,000 or less competed on the same playing field with Hollywood blockbusters from the major studios. Foreign films, subtitled or dubbed, also had to find theater space to recoup their investment, creating an informal chain of art house theaters not only in the United States, but also around the world. The movie business was in a way more egalitarian during the filmic era; everyone was angling for theatrical play dates, because it was the only place one could see a film when it first opened.

Those days are gone forever. Now, only the most expensive films get theatrical screenings – the franchise films, the DC and Marvel Universe films, the Bond films, Harry Potter, Star Wars and their ilk – while the rest are relegated to the relative limbo of unpublicised streaming releases, since DVDs have become an obsolete format, just as CDs have been replaced by streaming services for music. It makes perfect sense; the most expensive films are the biggest bets, so the studios throw all their ad dollars behind them, because they simply have to make their money back. With budgets now routinely hovering in the $200 to 300 million dollar range, this simply makes economic sense; why throw advertising dollars behind an interesting indie film, or a foreign import, when the latest Marvel film needs all the exposure it can get to recoup its cost?

But there’s another factor; without the theatrical “real estate” of a wide-break release, how can a film gain traction with an audience? Literally thousands of remarkable films are made each year on a worldwide basis that never get a theatrical release, and now, in the age of streaming, there’s no longer a video store where the clerk can suggest titles, and you can browse through various genres – it’s all online. One could argue that one can browse just as well on Amazon or Netflix, but it’s not the same; both services rely on rather clumsy algorithms to guess what you might be interested in next based in your last choice. These algorithms assume that if you like one horror film, then you’re going to like nothing but other horror films; stream a foreign film, and you’ll be inundated with more of the same.

There’s an upside to all of this, of course; it’s now cheaper than ever to make an independent film, and special effects that required a visit to an optical house can now be executed with the push of a button. Independent distribution platforms, such as YouTube, Mubi, Hulu, Kanopy, and others too numerous to mention offer instantaneous access to thousands of titles, and if you know what you’re looking for, you can probably find it online, legally or illegally. Sites like Vimeo specialise in making HD video distribution accessible to even the most impoverished cineaste; as a viewer, you can watch nearly all of the films on Vimeo for free, without even logging in. As a filmmaker, you can join Vimeo (at the lowest level) for free, and thus reach a wider audience than most experimental or independent films ever experience.

But the downside to all of this is the ineluctable march towards the teen and pre-teen market, as serious films become the province of micro cinemas, and adults are more or less marginalised in mainstream cinema. While there are some exceptions, the vast majority of what is either seen in theaters or on streaming services are either franchise films or comic book movies, with everything else pushed to the side. Teen cinema dominates. As I write this, for example, the box office is dominated by such films as Spider-Man: Far From Home, Toy Story 4, Yesterday, Aladdin, Annabelle Comes Home, John Wick 3: Parabellum – all remakes, sequels, or franchise films. Yet also available for screening right now, but not in mainstream theaters, are such interesting films as The Biggest Little Farm, Her Smell, High Life, Non-Fiction, Red Joan, The Wind, The Souvenir, The Fall of The American Empire, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Wild Rose, Echo in the Canyon – films that will never reach more than a few viewers because they have no advertising campaign behind them, and only the most dedicated viewers will ever even learn of their existence and seek them out.

Then, too, the relentless march of franchise and comic book films has dumbed down audiences to a remarkable degree; as someone who has taught university film courses for many years, I’ve witnessed the radical shift from earnest discussions of more difficult films in class, to the overwhelming influence of Comic-Con fandom, as cosplay replaces thoughtful analysis. There isn’t enough room here to go into the deleterious consequences of this shift, but as Quentin Tarantino becomes an “old school master” and Blumhouse keeps cranking out one horror movie after another in seemingly endless succession, it’s clear that the entire cinematic landscape has shifted into a new paradigm of pure escapist cinema, rather than offering mainstream films that provoke a more informed response.

Her Smell (Alex Ross Perry, 2019)

The shift to digital has made filmmaking cheaper and more available, but at the same time, even though streaming channels proliferate, getting noticed on them is more and more difficult, as the pace of film production hits a record level, and new players, such as Amazon Studios and Netflix, join the majors as significant production entities. Then, too, corporate consolidations, such as Disney’s recent acquisition of 21 st Century Fox (another addition to the Disney empire, which now embraces everything from amusement parks to television networks) will drive the mass media mentality of contemporary cinema even further towards the safe, the formulaic, with a plethora of remakes in the wings, rather than creating original content. Corporations only care about the bottom line, not individual visions.

And it isn’t over yet – not by a long shot. As the coming decades roll by, I predict that the comic book / franchise cinema juggernaut will show no signs of slowing down, driven both by economic circumstances (bigger budgets, saturation bookings on worldwide basis to recoup investments, with more interference from producers and focus groups and less input from directors) and the increasing audience need to escape a world that is more costly, more fragmented, and more inequitable than ever. Mainstream movies have become like Big Macs, seemingly filling but actually lacking in nutrition or cultural value. For the rest of us, the more thoughtful films will continue to be flung into the void. And mainstream audiences will never know, or care, that they even exist.

So, what happened? Digital took over, film is dead (except as a production medium for a handful of directors who still insist upon it), but everything winds up either as a DCP (Digital Cinema Package) for theatres, or goes straight to streaming. Audiences now, in a very fractured world, want safety, assurance, more of the same. They don’t want surprises. The new movie trailers spell out nearly every plot twist of the films they advertise, and audiences like it that way. They want to be led. They want to see something that’s just like what they just saw, only different. And clearly, from the box office numbers, the strategy seems to be working. The technology is not the problem – it offers great promise.

But instead, it has been used by the studios to reach out to the widest possible audience with the most carefully engineered and pretested product, designed to offend no one, and appeal to the greatest number of viewers. In short, I would argue that the cinema we knew has been replaced by a new sort of synthetic cinema, driven by CGI visual effects, simplistic plots, razor thin characters, and endless repetition of successful formulas. As the films of the 20 th century recede into the past, they will largely be forgotten – indeed, this is already happening – and we will be left with a perfect, flawless, digital world in which little that is human remains.

General Information

Help documents.

- Show Your Support!

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Business Information

- Services for Movie Theaters

- Contact Form

- BigScreen Featured Theaters

- Description of Major Features

- Digital Sound - Formats Explained

- Digital Sound on Film - Why Does It Matter?

- Gift Cards/Certificates - Where to Get Them

- How to Navigate this Site

- I'm having problems printing, help!

- Is BigScreen a complete movie database?

- Linking to The BigScreen Cinema Guide

- What do the ratings (G, PG, PG-13, R, NC-17) mean?

- What is 3D+ in HFR?

- What is Barco Auro 11.1 and Why Does it Matter?

- What is Digital Cinema Projection?

- What is Dolby Atmos and Why Does it Matter?

- What is DTS:X and Why Does it Matter?

- What is IMAX with Laser?

- What is Stadium Seating?

- What is THX?

- What's New - New Features, Revisions to this Site

The BigScreen Cinema Guide makes a point of highlighting movies showing with digital sound presentations, such as Digital Sound , Digital Sound 7.1 (for 7.1 channel presentations), Dolby Surround 7.1 (the Dolby-branded version), and Dolby Atmos , as well as the film-based formats of DTS Digital , Dolby Digital , and SDDS Sony Digital . These digital sound presentations are indicated by the use of the logos at the right throughout the schedule listings.

Note: As film-based presentations largely have given way to Digital Cinema Projection systems , the SDDS, DTS, and Dolby-branded formats (except for Dolby Surround 7.1 and Dolby Atmos) will disappear with them. When a theater does provide a film-based presentation with a digital sound format, we will provide that information when it is provided to us.

What About THX?

THX is not a digital sound format, but rather a certification for movie theaters that dictates the quality of the construction, the components used, and a calibration of the sound system that is repeated on a yearly basis. THX makes digital sound better!

For more information about THX, please see What is THX?

What Does A Digital Projector Do

- Technology & Innovation

- Virtual & Augmented Reality

Introduction

Welcome to the world of digital projectors, where movie nights, presentations, and immersive gaming experiences come to life. Gone are the days of bulky, cumbersome projectors that required complicated setups. The advent of digital technology has revolutionized the way we view and share content, and digital projectors have quickly become a staple in both professional and personal settings.

Whether you’re a business professional looking to deliver impactful presentations, an educator seeking to engage students in a dynamic learning environment, or a movie enthusiast in pursuit of a cinematic experience at home, a digital projector can fulfill your needs.

In this article, we will delve into the ins and outs of digital projectors, shedding light on what they are, how they work, the different types available, and key features to consider when purchasing one. We’ll also provide tips on setting up and using a digital projector for optimal performance, as well as guidance on maintenance and care to prolong its lifespan.

So, if you’re curious about the wonders a digital projector can offer, whether for personal or professional use, grab some popcorn, get comfortable, and let’s dive into the fascinating world of digital projectors.

What is a Digital Projector?

A digital projector, also known as a data projector or multimedia projector, is a device that takes an input signal, typically in the form of digital content, and projects it onto a screen or surface for viewing. It allows you to display images, videos, presentations, and other multimedia content on a larger scale, providing a more immersive and visually stunning experience.

Unlike traditional projectors that use analog technology, digital projectors utilize advanced digital imaging techniques to produce high-quality images with vibrant colors, sharp details, and enhanced clarity. They are capable of supporting various resolutions, including standard definition (SD), high definition (HD), and even ultra-high definition (UHD) or 4K resolutions, depending on the model.

One of the key advantages of digital projectors is their versatility. They can be connected to a wide range of devices, such as laptops, computers, smartphones, gaming consoles, and DVD players, through HDMI, VGA, or USB ports. This allows you to access and project content from different sources, making them suitable for a variety of applications, including business presentations, classroom teaching, home theater setups, and entertainment events.

Furthermore, digital projectors offer flexibility in terms of screen size. Depending on the model and the distance between the projector and the screen, you can adjust the image size to suit your needs, ranging from smaller projections for intimate settings to larger displays for audiences in auditoriums or outdoor venues.

Overall, digital projectors have become an indispensable tool for professionals, educators, and entertainment enthusiasts alike. They have revolutionized the way we share information, tell stories, and consume media, adding a new dimension to visual experiences and engaging audiences in captivating ways.

How Does a Digital Projector Work?

To understand how a digital projector works, let’s take a closer look at its fundamental components and the process involved in projecting images onto a screen.

At the core of a digital projector is a light source, typically a high-intensity lamp or LED, which emits a powerful beam of light. This light is directed towards an optical system consisting of lenses and mirrors that help focus and shape the light beam.

The next important component is the digital imaging device, which is responsible for converting the input signal into an image that can be projected. There are different types of imaging devices used in digital projectors, including liquid crystal display (LCD), digital light processing (DLP), and liquid crystal on silicon (LCOS).

In LCD projectors, the image is created by passing light through a series of tiny liquid crystal panels, each representing a pixel. These panels can selectively block or allow light to pass through, creating the desired image. DLP projectors utilize an array of mirrors that tilt in response to the input signal, reflecting light to create the image. LCOS projectors combine both LCD and DLP technologies to produce high-quality images.

Once the image is formed, it is passed through a color filter system that adds color to the image. This system typically uses red, green, and blue filters, which combine to produce a wide range of colors. The colored image then passes through another set of lenses that further refine the projection and adjust the focus.

Finally, the projected image is displayed on a screen or surface for viewing. The quality of the projection depends on factors such as the resolution of the imaging device, the brightness and contrast of the light source, and the quality of the optics used in the projector.

In addition to these main components, digital projectors often include other features to enhance performance and connectivity. These may include built-in speakers, keystone correction to adjust image distortion, zoom capabilities to adjust the image size without physically moving the projector, and various input ports for connecting external devices.

Overall, the process of a digital projector involves rendering the input signal into an image, applying color and focus adjustments, and projecting the image onto a surface, delivering a captivating visual experience for the audience.

The Components of a Digital Projector

A digital projector is composed of several crucial components that work together to create and project images onto a screen. Understanding these components can help you make informed decisions when choosing a projector that meets your specific needs and preferences.

1. Light Source: The light source is responsible for emitting a strong beam of light that illuminates the image being projected. Traditional projectors typically use high-intensity lamps, while newer models may use light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for improved energy efficiency and longevity.

2. Imaging Device: The imaging device plays a critical role in creating the image that will be projected. There are three primary types of imaging devices used in digital projectors:

- Liquid Crystal Display (LCD): LCD projectors use small liquid crystal panels to selectively block or allow light to pass through, creating the image pixel by pixel. They offer excellent color reproduction and sharp detail.

- Digital Light Processing (DLP): DLP projectors rely on an array of tiny mirrors that tilt to either reflect or not reflect light, effectively creating the image. DLP projectors are known for their high contrast ratios and smooth video playback.

- Liquid Crystal on Silicon (LCOS): LCOS projectors combine the best of LCD and DLP technologies, delivering high-quality images with exceptional color accuracy, contrast, and detail.

3. Optical System: The optical system consists of lenses and mirrors that help focus and shape the light beam produced by the light source. This system ensures that the projected image is clear, sharp, and properly aligned.

4. Color Filter System: The color filter system adds color to the image by using red, green, and blue filters. These three primary colors are combined in various combinations to produce a full spectrum of colors, resulting in vibrant and realistic images.

5. Lens System: The lens system is responsible for projecting the image onto the screen and determining the size and focus of the projection. The quality and type of lenses used can impact the sharpness, brightness, and clarity of the projected image.

6. Signal Processing: Digital projectors include signal processing capabilities to handle the input signal and convert it into a format suitable for projection. This processing ensures that the image is properly scaled, optimized, and adjusted to match the capabilities of the projector.

7. Connectivity and Control Interfaces: Projectors offer various input ports such as HDMI, VGA, and USB, allowing you to connect different devices like computers, laptops, gaming consoles, and media players. Additionally, projectors may include built-in Wi-Fi or Ethernet connectivity for seamless wireless presentations and remote control options.

By understanding the components of a digital projector, you can evaluate and compare different models to find the one that best suits your specific requirements, whether it’s for professional presentations, home theater setups, or educational purposes.

Types of Digital Projectors

When it comes to digital projectors, there are several types available, each with its own unique features, strengths, and applications. Understanding the different types can help you choose the one that best suits your specific needs and preferences. Let’s explore some of the most common types of digital projectors:

- Portable Projectors: As the name suggests, portable projectors are lightweight and compact, making them highly convenient for on-the-go use. These projectors are typically smaller in size and offer lower brightness levels compared to larger models. They are commonly used for impromptu presentations, movie nights, and classrooms where mobility and flexibility are important.

- Business Projectors: Business projectors are designed specifically for professional settings and presentations. They offer high brightness levels, sharp image quality, and advanced connectivity options to accommodate various business needs. Features like keystone correction, multiple input ports, and wireless connectivity make these projectors ideal for boardrooms, conference rooms, and corporate events.

- Home Theater Projectors: Home theater projectors are built to provide a cinematic experience in the comfort of your own home. These projectors offer high resolution, vibrant color reproduction, and wide aspect ratios to deliver immersive images. They are often used in dedicated home theater rooms or living rooms to project movies, TV shows, and sporting events on a large screen.

- Short-Throw and Ultra-Short-Throw Projectors: Short-throw and ultra-short-throw projectors are designed to project large images from a short distance. These projectors eliminate the need for extensive space between the projector and the screen, making them ideal for smaller rooms and spaces where a traditional projector setup would not be feasible. They are commonly used in classrooms, small offices, and home entertainment setups.

- Gaming Projectors: Gaming projectors are specifically optimized for gaming enthusiasts who want larger-than-life gaming experiences. These projectors offer fast response times, high refresh rates, and low input lag to ensure smooth and immersive gameplay. They often come with gaming-specific features such as Game Mode settings and enhanced color accuracy for a dynamic and captivating gaming experience.

- Interactive Projectors: Interactive projectors are equipped with touch-sensitive capabilities, allowing users to interact directly with the projected image using touch or gestures. These projectors are commonly used in classrooms, training sessions, and collaborative environments, enabling interactive learning, brainstorming, and engagement.

When choosing a digital projector, consider the intended use, lighting conditions, required image quality, and available space to determine the most suitable type. It is important to carefully assess the features and specifications of each type to find the projector that perfectly aligns with your specific requirements.

Key Features to Consider

When selecting a digital projector, it’s essential to consider certain key features that can greatly impact your overall viewing experience and usability. These features will help you find a projector that meets your specific needs and delivers optimal performance. Here are some crucial features to consider:

- Resolution: The resolution of the projector determines the level of detail and clarity in the projected image. Common resolutions include HD (1280×720 pixels), Full HD (1920×1080 pixels), and 4K UHD (3840×2160 pixels). Choose a resolution that matches your content and desired image quality.

- Brightness: The brightness of a projector is measured in lumens and determines how well the image will be visible in various lighting conditions. Consider the ambient light in your environment and the size of the projected image when choosing the appropriate brightness level. Higher lumens are recommended for brighter spaces or larger screens.

- Contrast Ratio: The contrast ratio refers to the difference between the darkest and brightest parts of an image. A higher contrast ratio produces more lifelike and vibrant images with better color accuracy. Look for projectors with a high contrast ratio for improved image quality.

- Connectivity: Check the available connectivity options on the projector to ensure compatibility with your devices. HDMI, VGA, and USB ports are commonly used for connecting laptops, computers, gaming consoles, and media players. Some projectors also offer wireless connectivity for convenient streaming and screen mirroring.

- Throw Distance: The throw distance is the distance between the projector and the screen required to achieve a specific image size. Consider the available space and the desired screen size when choosing a projector with the appropriate throw distance capabilities.

- Noise Level: Projectors contain cooling fans and other internal components that can produce noise. If you plan to use the projector in a quiet environment, look for models with lower noise levels or consider investing in a projector enclosure or soundproofing options to mitigate the noise.

- Zoom and Lens Shift: Zoom and lens shift features provide flexibility in adjusting the image size and positioning without physically moving the projector. This allows for easier setup and adaptation to different screen sizes and room configurations.

- Aspect Ratio: The aspect ratio refers to the width-to-height ratio of the projected image. Common aspect ratios include 16:9 (widescreen) and 4:3 (standard). Choose the aspect ratio that best suits your content, whether it’s for movies, presentations, or gaming.

- Available Accessories: Consider the availability of additional accessories such as ceiling mounts, projector screens, and carrying bags. These accessories can enhance the usability and convenience of your projector setup.

By carefully considering these key features, you can select a digital projector that delivers the image quality, connectivity options, and overall functionality that align with your specific needs and preferences. Take the time to research and compare different models to find the perfect fit for your intended use and budget.

Choosing the Right Digital Projector for Your Needs

Choosing the right digital projector can greatly enhance your viewing experience, whether for business presentations, home theater setups, or educational purposes. To ensure you select the projector that best suits your needs, consider the following factors:

- Intended Use: Determine the primary purpose of the projector. Are you using it for professional presentations, movie nights, gaming, or educational use? This will help you identify the features and specifications required for your specific use case.

- Budget: Set a budget for your projector purchase. Determine the price range that aligns with your needs and explore options within that range. Balance your budget with the features and quality you require.

- Room Size and Ambient Lighting: Consider the size of the room and the lighting conditions. For larger rooms or spaces with significant ambient light, look for a projector with higher brightness levels and a higher contrast ratio to ensure clear and vibrant images.

- Image Quality: Evaluate the resolution, contrast ratio, and color accuracy of the projector. Higher resolutions and contrast ratios, along with accurate color reproduction, can elevate your viewing experience and make the content more engaging and immersive.

- Connectivity Options: Check the connectivity options offered by the projector. Ensure it has the necessary input ports to connect your devices, such as HDMI, VGA, or USB. Wireless connectivity can also be a useful feature for seamless streaming and screen mirroring.

- Portability: Consider whether you need a portable projector that can be easily moved and set up in different locations. Portable projectors are lightweight and compact, making them convenient for business professionals, educators, or anyone on the go.

- User-Friendly Interface: Look for a projector with an intuitive and easy-to-use interface. A user-friendly interface will simplify the setup and navigation process, ensuring a smoother and more enjoyable experience.

- Reviews and Recommendations: Read customer reviews and seek recommendations from trusted sources. Consider the experiences of others who have used the projector you’re interested in to gain insights into its performance, reliability, and overall value.

- Warranty and Customer Support: Check the warranty and customer support options provided with the projector. A reputable brand that offers reliable warranty coverage and responsive customer support can provide peace of mind and assistance if any issues arise.

By considering these factors, you can make an informed decision when choosing the right digital projector for your specific needs. Remember to prioritize features that are important for your intended use, while staying within your budget, and select a projector from a reputable brand with positive reviews and reliable customer support.

Setting up and Using a Digital Projector

Setting up and using a digital projector may seem daunting at first, but with a few simple steps, you can easily enjoy the benefits of a larger screen and immersive viewing experience. Here’s a guide to help you set up and effectively use your digital projector:

- Choose the Right Location: Select a suitable location where you will set up your projector. Consider factors such as distance from the screen or wall, availability of power outlets, and ambient lighting conditions.

- Positioning the Projector: Place the projector on a stable surface or mount it securely if using a ceiling mount. Ensure that the projector is aligned with the center of the screen and perpendicular to it for optimal image quality.

- Connect Your Devices: Connect your devices, such as a laptop or media player, to the projector using the appropriate cables or wireless connectivity options. Make sure the projector is powered on and set to the correct input source to receive the signal from your device.

- Adjusting the Image: Adjust the zoom, focus, and keystone correction settings on the projector to obtain a clear and properly aligned image. Some projectors may have automatic adjustment features to simplify this process.

- Screen Selection: If you have a dedicated projection screen, ensure it is clean and properly mounted. Alternatively, you can use a blank wall or a white screen surface to project the image. Avoid textured or colored walls, as they may affect the image quality.

- Test and Fine-Tune: Once the setup is complete, test the projected image for clarity, brightness, and color accuracy. Make any necessary adjustments to achieve the desired picture quality.

- Audio Setup: If the projector has built-in speakers, ensure they are enabled and adjust the volume as needed. For a more immersive audio experience, consider connecting external speakers or a sound system to enhance the sound quality.

- Remote Control: Familiarize yourself with the functions and controls on the projector’s remote control. This will allow you to easily adjust settings, switch input sources, and navigate through menus without needing to use the physical buttons on the projector.

- Proper Shutdown: When you are finished using the projector, shut it down using the proper procedure outlined in the manual. Allow the projector to cool down before moving or storing it to avoid any damage.

- Maintenance: Regularly clean the projector lens and air vents to prevent dust buildup, which can affect image quality and cause overheating. Refer to the manufacturer’s instructions for specific cleaning guidelines.

By following these steps and taking proper care of your digital projector, you can enjoy seamless setup and optimal performance for a variety of applications. Remember to consult the user manual provided by the manufacturer for detailed instructions specific to your projector model.

Tips for Maximizing the Performance of Your Digital Projector

A digital projector can provide you with stunning visuals and an immersive viewing experience. To ensure you get the most out of your projector and optimize its performance, consider the following tips:

- Ensure Proper Ventilation: Make sure your projector has adequate space around it for airflow. Avoid placing it in enclosed spaces or near other heat-generating devices as it can lead to overheating and reduced performance.

- Regularly Clean the Lens: Dust and smudges on the lens can affect image quality. Clean the lens periodically with a soft, lint-free cloth to maintain optimal clarity and sharpness.

- Use the Correct Aspect Ratio: Set the correct aspect ratio on your projector to match the content you are viewing. This ensures that the image is displayed in the correct proportions without distortion.

- Manage Ambient Light: Minimize ambient light in the viewing area to enhance image clarity and contrast. Use curtains or blinds to block out external light sources and create a darker environment for better viewing conditions.

- Adjust Brightness and Contrast: Optimize the brightness and contrast settings based on the lighting conditions in the room. You can increase brightness in well-lit areas and adjust contrast to enhance the details in darker scenes.

- Calibrate Colors: Use the color calibration settings on your projector to adjust color accuracy and ensure vibrant and true-to-life visuals. Some projectors also offer pre-set color modes for different types of content.

- Avoid Image Distortion: Make sure the projector is positioned at the correct angle and distance to avoid keystone distortion. Adjust the keystone correction settings on the projector or use a mount to maintain a square image.

- Optimize Audio Setup: If the projector has built-in speakers, consider using external speakers or a sound system for better audio quality. Position the speakers appropriately to achieve a balanced and immersive sound experience.

- Control Ambient Noise: Minimize any unnecessary noise in the viewing area, as it can detract from the overall viewing experience. Close windows, turn off fans or other appliances, and choose a quieter projection location if possible.

- Update Firmware and Software: Check for firmware and software updates regularly from the manufacturer’s website. Keeping your projector’s software up to date ensures you have access to the latest features and bug fixes.

By implementing these tips, you can optimize the performance of your digital projector and fully enjoy your viewing experience. Experiment with various settings and adjustments to find the perfect balance for your specific environment and content.

Maintenance and Care for a Digital Projector

To ensure the longevity and optimal performance of your digital projector, proper maintenance and care are essential. By following these maintenance tips, you can extend the lifespan of your projector and enjoy consistent image quality:

- Regular Cleaning: Keep the projector clean by regularly cleaning the exterior and air vents. Use a soft, lint-free cloth to wipe away dust and smudges. Avoid using abrasive materials or liquid cleaners that may damage the surface.

- Clean the Filter: If your projector has an air filter, regularly check and clean it according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A clogged or dirty filter can cause overheating and impact image quality.

- Avoid Excessive Heat: Keep the projector in a well-ventilated area and avoid exposing it to direct sunlight or extreme temperatures. Excessive heat can damage the internal components and reduce the projector’s lifespan.

- Proper Shutdown: Always turn off the projector using the proper shutdown procedure outlined in the user manual. This allows the projector’s internal components to cool down before it is powered off completely.

- Avoid Moving the Projector While in Use: Do not move the projector while it is powered on or in use. Allow it to cool down and power off before relocating or packing it away.

- Storage Guidelines: If you need to store the projector for an extended period, ensure it is stored in a clean, dry, and dust-free environment. Use the original packaging or a protective case to prevent any damage during storage.

- Keep the Projector Dust-Free: Regularly clean the projector’s lens and ventilation ports to prevent dust buildup. Dust can block airflow and cause overheating, affecting the projector’s performance and image quality.

- Avoid Power Surges: Protect the projector from power surges by using a surge protector or uninterruptible power supply (UPS). Power surges can damage the internal components of the projector.

- Follow Lamp Replacement Guidelines: If your projector uses a replaceable lamp, follow the manufacturer’s guidelines for lamp replacement. Overused or expired lamps can result in decreased brightness and image quality.

- Regularly Update Firmware: Check for firmware updates from the manufacturer’s website and update your projector’s firmware as recommended. Firmware updates can address bugs, improve performance, and introduce new features.

- Read the User Manual: Familiarize yourself with the user manual to understand the specific maintenance requirements and guidelines for your projector model. The user manual provides valuable information on proper care and troubleshooting.

By implementing these maintenance and care practices, you can prolong the lifespan of your digital projector and maintain optimal performance. Regular cleaning, proper storage, and following the manufacturer’s guidelines are key to ensuring an optimal viewing experience over the projector’s lifespan.

Digital projectors have revolutionized the way we view and share content, providing us with larger-than-life visuals and immersive experiences. Whether for business presentations, educational purposes, or home entertainment setups, choosing the right digital projector can greatly enhance your viewing experience.

In this article, we explored the various aspects of digital projectors, starting with what they are and how they work. We discussed the key components of a digital projector, including the light source, imaging device, and color filter system. We also looked at different types of projectors, such as portable projectors, business projectors, home theater projectors, gaming projectors, interactive projectors, and more.

We then highlighted the key features to consider when selecting a digital projector, such as resolution, brightness, connectivity options, and throw distance. These factors play a crucial role in determining the overall performance and suitability of the projector for your specific needs.

Additionally, we provided tips on setting up and using a digital projector effectively, including proper positioning, screen selection, adjusting image settings, optimizing audio setup, and following correct shutdown procedures. We also discussed the importance of maintenance and care to prolong the lifespan of the projector, covering cleaning, avoiding excessive heat, and following manufacturer guidelines.

By considering all these aspects and implementing the recommended practices, you can maximize the performance, lifespan, and enjoyment of your digital projector. Remember to research and compare different models, read customer reviews, and seek recommendations to make an informed decision.

So, whether you’re presenting to a boardroom, hosting a movie night at home, or engaging students in a classroom setting, a digital projector can elevate your visual experiences and captivate your audience. Embrace the possibilities and bring your content to life with the magic of a digital projector.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Crowdfunding

- Cryptocurrency

- Digital Banking

- Digital Payments

- Investments

- Console Gaming

- Mobile Gaming

- VR/AR Gaming

- Gadget Usage

- Gaming Tips

- Online Safety

- Software Tutorials

- Tech Setup & Troubleshooting

- Buyer’s Guides

- Comparative Analysis

- Gadget Reviews

- Service Reviews

- Software Reviews

- Mobile Devices

- PCs & Laptops

- Smart Home Gadgets

- Content Creation Tools

- Digital Photography

- Video & Music Streaming

- Online Security

- Online Services

- Web Hosting

- WiFi & Ethernet

- Browsers & Extensions

- Communication Platforms

- Operating Systems

- Productivity Tools

- AI & Machine Learning

- Cybersecurity

- Emerging Tech

- IoT & Smart Devices

- Virtual & Augmented Reality

- Latest News

- AI Developments

- Fintech Updates

- Gaming News

- New Product Launches

- Fintechs and Traditional Banks Navigating the Future of Financial Services

- AI Writing How Its Changing the Way We Create Content

Related Post

How to find the best midjourney alternative in 2024: a guide to ai anime generators, unleashing young geniuses: how lingokids makes learning a blast, 10 best ai math solvers for instant homework solutions, 10 best ai homework helper tools to get instant homework help, 10 best ai humanizers to humanize ai text with ease, sla network: benefits, advantages, satisfaction of both parties to the contract, related posts.

15 Best Art Projector For 2024

13 Amazing Digital Projector For 2024

10 Best Slide Projector For Old Slides For 2024

14 Amazing Anker Projector For 2024

15 Best Nebula Projector For 2024

13 Amazing Overhead Projector For 2024

14 Amazing HDMI Projector for 2024

9 Amazing Slide Projector For 2024

Recent stories.

Fintechs and Traditional Banks: Navigating the Future of Financial Services

AI Writing: How It’s Changing the Way We Create Content

How to Know When it’s the Right Time to Buy Bitcoin

How to Sell Counter-Strike 2 Skins Instantly? A Comprehensive Guide

10 Proven Ways For Online Gamers To Avoid Cyber Attacks And Scams

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

POST-CINEMA

Theorizing 21st-Century Film

1.1 What is Digital Cinema?

By lev manovich.

Cinema, the Art of the Index [1]

Thus far, most discussions of cinema in the digital age have focused on the possibilities of interactive narrative. It is not hard to understand why: since the majority of viewers and critics equate cinema with storytelling, digital media is understood as something that will let cinema tell its stories in a new way. Yet as exciting as the ideas of a viewer participating in a story, choosing different paths through the narrative space, and interacting with characters may be, they only address one aspect of cinema which is neither unique nor, as many will argue, essential to it: narrative.

The challenge which digital media poses to cinema extends far beyond the issue of narrative. Digital media redefines the very identity of cinema. In a symposium that took place in Hollywood in the spring of 1996, one of the participants provocatively referred to movies as “flatties” and to human actors as “organics” and “soft fuzzies.” [2] As these terms accurately suggest, what used to be cinema’s defining characteristics have become just the default options, with many others available. When one can “enter” a virtual three-dimensional space, viewing flat images projected on the screen is hardly the only option. When, given enough time and money, almost everything can be simulated in a computer, filming physical reality is just one possibility.

This “crisis” of cinema’s identity also affects the terms and the categories used to theorize cinema’s past. French film theorist Christian Metz wrote in the 1970s that “Most films shot today, good or bad, original or not, ‘commercial’ or not, have as a common characteristic that they tell a story; in this measure they all belong to one and the same genre, which is, rather, a sort of ‘super-genre’ [‘ sur-genre ’]” (402). In identifying fictional films as a “super-genre” of 20th-century cinema, Metz did not bother to mention another characteristic of this genre because at that time it was too obvious: fictional films are live-action films, i.e. they largely consist of unmodified photographic recordings of real events which took place in real physical space. Today, in the age of computer simulation and digital compositing, invoking this characteristic becomes crucial in defining the specificity of 20th-century cinema. From the perspective of a future historian of visual culture, the differences between classical Hollywood films, European art films, and avant-garde films (apart from abstract ones) may appear less significant than this common feature: that they relied on lens-based recordings of reality. This essay is concerned with the effect of the so-called digital revolution on cinema as defined by its “super-genre” of fictional live-action film. [3]

During cinema’s history, a whole repertoire of techniques (lighting, art direction, the use of different film stocks and lenses, etc.) was developed to modify the basic record obtained by a film apparatus. And yet behind even the most stylized cinematic images we can discern the bluntness, the sterility, the banality of early 19th-century photographs. No matter how complex its stylistic innovations, the cinema has found its base in these deposits of reality, these samples obtained by a methodical and prosaic process. Cinema emerged out of the same impulse that engendered naturalism, court stenography, and wax museums. Cinema is the art of the index; it is an attempt to make art out of a footprint.

Even for Andrei Tarkovsky, film-painter par excellence, cinema’s identity lay in its ability to record reality. Once, during a public discussion in Moscow in the 1970s, he was asked the question as to whether he was interested in making abstract films. He replied that there can be no such thing. Cinema’s most basic gesture is to open the shutter and to start the film rolling, recording whatever happens to be in front of the lens. For Tarkovsky, an abstract cinema is thus impossible.

But what happens to cinema’s indexical identity if it is now possible to generate photorealistic scenes entirely in a computer using 3-D computer animation; to modify individual frames or whole scenes with the help a digital paint program; to cut, bend, stretch and stitch digitized film images into something which has perfect photographic credibility, although it was never actually filmed?

This essay will address the meaning of these changes in the filmmaking process from the point of view of the larger cultural history of the moving image. Seen in this context, the manual construction of images in digital cinema represents a return to 19th-century pre-cinematic practices, when images were hand-painted and hand-animated. At the turn of the 20th century, cinema was to delegate these manual techniques to animation and define itself as a recording medium. As cinema enters the digital age, these techniques are again becoming commonplace in the filmmaking process. Consequently, cinema can no longer be clearly distinguished from animation. It is no longer an indexical media technology but, rather, a sub-genre of painting.

This argument will be developed—in three stages. I will first follow a historical trajectory from 19th-century techniques for creating moving images to 20th-century cinema and animation. Next I will arrive at a definition of digital cinema by abstracting the common features and interface metaphors of a variety of computer software and hardware that are currently replacing traditional film technology. Seen together, these features and metaphors suggest a distinct logic of a digital moving image. This logic subordinates the photographic and the cinematic to the painterly and the graphic, destroying cinema’s identity as a media art. Finally, I will examine different production contexts that already use digital moving images—Hollywood films, music videos, CD-ROM games and artworks—in order to see if and how this logic has begun to manifest itself.

A Brief Archaeology of Moving Pictures

As signified by its original names (kinetoscope, cinematograph, moving pictures), cinema was understood, from its birth, as the art of motion, the art that finally succeeded in creating a convincing illusion of dynamic reality. If we approach cinema in this way (rather than the art of audio-visual narrative, or the art of a projected image, or the art of collective spectatorship, etc.), we can see it superseding previous techniques for creating and displaying moving images.

These earlier techniques shared a number of common characteristics. First, they all relied on hand-painted or hand-drawn images. The magic lantern slides were painted at least until the 1850s; so were the images used in the Phenakistiscope, the Thaumatrope, the Zoetrope, the Praxinoscope, the Choreutoscope and numerous other 19th-century pre-cinematic devices. Even Muybridge’s celebrated Zoopraxiscope lectures of the 1880s featured not actual photographs but colored drawings painted after the photographs (Musser 49-50).

Not only were the images created manually, they were also manually animated. In Robertson’s Phantasmagoria, which premiered in 1799, magic lantern operators moved behind the screen in order to make projected images appear to advance and withdraw (Musser 25). More often, an exhibitor used only his hands, rather than his whole body, to put the images into motion. One animation technique involved using mechanical slides consisting of a number of layers. An exhibitor would slide the layers to animate the image (Ceram 44-45). Another technique was to slowly move a long slide containing separate images in front of a magic lantern lens. 19th-century optical toys enjoyed in private homes also required manual action to create movement—twirling the strings of the Thaumatrope, rotating the Zoetrope’s cylinder, turning the Viviscope’s handle.

It was not until the last decade of the 19th century that the automatic generation of images and their automatic projection were finally combined. A mechanical eye was coupled with a mechanical heart; photography met the motor. As a result, cinema—a very particular regime of the visible—was born. Irregularity, non-uniformity, the accident and other traces of the human body, which previously inevitably accompanied moving image exhibitions, were replaced by the uniformity of machine vision. [4] A machine that, like a conveyer belt, was now spitting out images, all sharing the same appearance, all the same size, all moving at the same speed, like a line of marching soldiers.

Cinema also eliminated the discrete character of both space and movement in moving images. Before cinema, the moving element was visually separated from the static background as with a mechanical slide show or Reynaud’s Praxinoscope Theater (1892) (Robinson 12). The movement itself was limited in range and affected only a clearly defined figure rather than the whole image. Thus, typical actions would include a bouncing ball, a raised hand or eyes, a butterfly moving back and forth over the heads of fascinated children—simple vectors charted across still fields.

Cinema’s most immediate predecessors share something else. As the 19th-century obsession with movement intensified, devices that could animate more than just a few images became increasingly popular. All of them—the Zoetrope, the Phonoscope, the Tachyscope, the Kinetoscope—were based on loops, sequences of images featuring complete actions which can be played repeatedly. The Thaumatrope (1825), in which a disk with two different images painted on each face was rapidly rotated by twirling a string attached to it, was in its essence a loop in its most minimal form: two elements replacing one another in succession. In the Zoetrope (1867) and its numerous variations, approximately a dozen images were arranged around the perimeter of a circle. [5] The Mutoscope, popular in America throughout the 1890s, increased the duration of the loop by placing a larger number of images radially on an axle (Ceram 140). Even Edison’s Kinetoscope (1892-1896), the first modern cinematic machine to employ film, continued to arrange images in a loop (Musser 78). 50 feet of film translated to an approximately 20-second long presentation—a genre whose potential development was cut short when cinema adopted a much longer narrative form.

From Animation to Cinema

Once the cinema was stabilized as a technology, it cut all references to its origins in artifice. Everything which characterized moving pictures before the 20th century—the manual construction of images, loop actions, the discrete nature of space and movement—was delegated to cinema’s bastard relative, its supplement, its shadow—animation. 20th-century animation became a depository for 19th-century moving-image techniques left behind by cinema.

The opposition between the styles of animation and cinema defined the culture of the moving image in the 20th century. Animation foregrounds its artificial character, openly admitting that its images are mere representations. Its visual language is more aligned to the graphic than to the photographic. It is discrete and self-consciously discontinuous: crudely rendered characters moving against a stationary and detailed background; sparsely and irregularly sampled motion (in contrast to the uniform sampling of motion by a film camera—recall Jean-Luc Godard’s definition of cinema as “truth 24 frames per second”), and finally space constructed from separate image layers.

In contrast, cinema works hard to erase any traces of its own production process, including any indication that the images we see could have been constructed rather than recorded. It denies that the reality it shows often does not exist outside of the film image, the image which was arrived at by photographing an already impossible space, itself put together with the use of models, mirrors, and matte paintings, and which was then combined with other images through optical printing. It pretends to be a simple recording of an already existing reality—both to a viewer and to itself. [6] Cinema’s public image stressed the aura of reality “captured” on film, thus implying that cinema was about photographing what existed before the camera, rather than “creating the ‘never-was’” of special effects. [7] Rear projection and blue-screen photography, matte paintings and glass shots, mirrors and miniatures, push development, optical effects and other techniques which allowed filmmakers to construct and alter the moving images, and thus could reveal that cinema was not really different from animation, were pushed to cinema’s periphery by its practitioners, historians, and critics. [8] Today, with the shift to digital media, these marginalized techniques move to the center.

What is Digital Cinema?

A visible sign of this shift is the new role that computer-generated special effects have come to play in Hollywood industry in the last few years. Many recent blockbusters have been driven by special effects, feeding on their popularity. Hollywood has even created a new mini-genre of “The Making of” videos and books, which reveal how special effects are created.

I will use special effects from a few recent Hollywood films for illustrations of some of the possibilities of digital filmmaking. Until recently, Hollywood studios were the only ones who had the money to pay for digital tools and for the labor involved in producing digital effects. However, the shift to digital media affects not just Hollywood, but filmmaking as a whole. As traditional film technology is universally being replaced by digital technology, the logic of the filmmaking process is being redefined. What I describe below are the new principles of digital filmmaking, which are equally valid for individual or collective film productions, regardless of whether they are using the most expensive professional hardware and software or amateur equivalents. Consider, then, the following principles of digital filmmaking:

- Rather than filming physical reality it is now possible to generate film-like scenes directly in a computer with the help of 3-D computer animation. Therefore, live-action footage is displaced from its role as the only possible material from which the finished film is constructed.

- Once live-action footage is digitized (or directly recorded in a digital format), it loses its privileged indexical relationship to pro-filmic reality. The computer does not distinguish between an image obtained through the photographic lens, an image created in a paint program, or an image synthesized in a 3-D graphics package, since they are made from the same material—pixels. And pixels, regardless of their origin, can be easily altered, substituted one for another, and so on. Live-action footage is reduced to just another graphic, no different from images that were created manually. [9]

- If live-action footage was left intact in traditional filmmaking, now it functions as raw material for further compositing, animating, and morphing. As a result, while retaining visual realism unique to the photographic process, film obtains the plasticity that was previously only possible in painting or animation. To use the suggestive title of a popular morphing software, digital filmmakers work with “elastic reality.” For example, the opening shot of Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis 1994; special effects by Industrial Light and Magic) tracks an unusually long and extremely intricate flight of a feather. To create the shot, the real feather was filmed against a blue background in different positions; this material was then animated and composited against shots of a landscape. [10] The result: a new kind of realism, which can be described as “something that looks as if it is intended to look exactly as if it could have happened, although it really could not.”

- Previously, editing and special effects were strictly separate activities. An editor worked on ordering sequences of images together; any intervention within an image was handled by special-effects specialists. The computer collapses this distinction. The manipulation of individual images via a paint program or algorithmic image processing becomes as easy as arranging sequences of images in time. Both simply involve “cut and paste.” As this basic computer command exemplifies, modification of digital images (or other digitized data) is not sensitive to distinctions of time and space or of differences of scale. Thus, re-ordering sequences of images in time, compositing them together in space, modifying parts of an individual image, and changing individual pixels become the same operation, conceptually and practically.

- Given the preceding principles, we can define digital film in this way:

digital film = live action material + painting + image processing + compositing + 2-D computer animation + 3-D computer animation

Live-action material can be recorded either on film or video or directly in a digital format. [11] Painting, image processing, and computer animation refer to the processes of modifying already existent images as well as creating new ones. In fact, the very distinction between creation and modification, so clear in film-based media (shooting versus darkroom processes in photography, production versus post-production in cinema) no longer applies to digital cinema, since each image, regardless of its origin, goes through a number of programs before making it to the final film. [12]

Let us summarize the principles discussed thus far. Live action footage is now only raw material to be manipulated by hand: animated, combined with 3-D computer-generated scenes, and painted over. The final images are constructed manually from different elements, and all the elements are either created entirely from scratch or modified by hand.

We can finally answer the question “What is digital cinema?” Digital cinema is a particular case of animation that uses live-action footage as one of its many elements.

This can be re-read in view of the history of the moving image sketched earlier. Manual construction and animation of images gave birth to cinema and slipped into the margins, only to re-appear as the foundation of digital cinema. The history of the moving image thus comes full circle. Born from animation, cinema pushed animation to its boundary, only to become one particular case of animation in the end .

The relationship between “normal” filmmaking and special effects is similarly reversed. Special effects, which involved human intervention into machine-recorded footage and which were therefore delegated to cinema’s periphery throughout its history, become the norm of digital filmmaking.

The same applies for the relationship between production and post-production. Cinema traditionally involved arranging physical reality to be filmed though the use of sets, models, art direction, cinematography, etc. Occasional manipulation of recorded film (for instance, through optical printing) was negligible compared to the extensive manipulation of reality in front of a camera. In digital filmmaking, shot footage is no longer the final point but just raw material to be manipulated in a computer where the real construction of a scene will take place. In short, the production becomes just the first stage of post-production.

The following examples illustrate this shift from re-arranging reality to re-arranging its images. From the analog era: for a scene in Zabriskie Point (1970), Michelangelo Antonioni, trying to achieve a particularly saturated color, ordered a field of grass to be painted. From the digital era: to create the launch sequence in Apollo 13 (Ron Howard 1995; special effects by Digital Domain), the crew shot footage at the original location of the launch at Cape Canaveral. The artists at Digital Domain scanned the film and altered it on computer workstations, removing recent building construction, adding grass to the launch pad and painting the skies to make them more dramatic. This altered film was then mapped onto 3-D planes to create a virtual set that was animated to match a 180-degree dolly movement of a camera following a rising rocket (see Robertson 20).

The last example brings us to yet another conceptualization of digital cinema—as painting. In his book-length study of digital photography, William J.T. Mitchell focuses our attention on what he calls the inherent mutability of a digital image:

The essential characteristic of digital information is that it can be manipulated easily and very rapidly by computer. It is simply a matter of substituting new digits for old. . . . Computational tools for transforming, combining, altering, and analyzing images are as essential to the digital artist as brushes and pigments to a painter. (7)

As Mitchell points out, this inherent mutability erases the difference between a photograph and a painting. Since a film is a series of photographs, it is appropriate to extend Mitchell’s argument to digital film. With an artist being able to easily manipulate digitized footage either as a whole or frame by frame, a film in a general sense becomes a series of paintings. [13]

Hand-painting digitized film frames, made possible by a computer, is probably the most dramatic example of the new status of cinema. No longer strictly locked in the photographic, it opens itself towards the painterly. It is also the most obvious example of the return of cinema to its 19th-century origins—in this case, to hand-crafted images of magic lantern slides, the Phenakistiscope, the Zoetrope.

We usually think of computerization as automation, but here the result is the reverse: what was previously automatically recorded by a camera now has to be painted one frame at a time. But not just a dozen images, as in the 19th century, but thousands and thousands. We can draw another parallel with the practice, common in the early days of silent cinema, of manually tinting film frames in different colors according to a scene’s mood (see Robinson 165). Today, some of the most visually sophisticated digital effects are often achieved using the same simple method: painstakingly altering by hand thousands of frames. The frames are painted over either to create mattes (hand-drawn matte extraction) or to directly change the images, as in Forrest Gump , where President Kennedy was made to speak new sentences by altering the shape of his lips, one frame at a time. [14] In principle, given enough time and money, one can create what will be the ultimate digital film: 90 minutes, i.e. 129,600 frames, completely painted by hand from scratch, but indistinguishable in appearance from live photography. [15]

Multimedia as “Primitive” Digital Cinema

3-D animation, compositing, mapping, paint retouching: in commercial cinema, these radical new techniques are mostly used to solve technical problems while traditional cinematic language is preserved unchanged. Frames are hand-painted to remove wires that supported an actor during shooting; a flock of birds is added to a landscape; a city street is filled with crowds of simulated extras. Although most Hollywood releases now involve digitally manipulated scenes, the use of computers is always carefully hidden. [16]