51 Constructive Feedback Examples for Students

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Constructive feedback is feedback that helps students learn and grow.

Even though it highlights students’ weaknesses, it is not negative feedback because it has a purpose. It is designed to help them identify areas for improvement.

It serves both as an example of positive reinforcement and a reminder that there is always room for further improvement. Studies show that students generally like feedback that points them in the right direction and helps them to improve. It can also increase motivation for students.

Why Give Constructive Feedback?

Constructive feedback is given to help students improve. It can help people develop a growth mindset by helping them understand what they need to do to improve.

It can also help people to see that their efforts are paying off and that they can continue to grow and improve with continued effort.

Additionally, constructive feedback helps people to feel supported and motivated to keep working hard. It shows that we believe in their ability to grow and succeed and that we are willing to help them along the way.

How to Give Constructive Feedback

Generally, when giving feedback, it’s best to:

- Make your feedback specific to the student’s work

- Point out areas where the student showed effort and where they did well

- Offer clear examples of how to improve

- Be positive about the student’s prospects if they put in the hard work to improve

- Encourage the student to ask questions if they don’t understand your feedback

Furthermore, it is best to follow up with students to see if they have managed to implement the feedback provided.

General Constructive Feedback Examples for Students

The below examples are general templates that need to be edited so they are specific to the student’s work.

1. You are on the right track. By starting to study for the exam earlier, you may be able to retain more knowledge on exam day.

2. I have seen your improvement over time. As a next step, it is a good idea to…

3. You have improved a lot and should start to look towards taking on harder tasks for the future to achieve more self-development.

4. You have potential and should work on your weaknesses to achieve better outcomes. One area for improvement is…

5. Keep up the good work! You will see better results in the future if you make the effort to attend our study groups more regularly.

6. You are doing well, but there is always room for improvement. Try these tips to get better results: …

7. You have made some good progress, but it would be good to see you focusing harder on the assignment question so you don’t misinterpret it next time.

8. Your efforts are commendable, but you could still do better if you provide more specific examples in your explanations.

9. You have done well so far, but don’t become complacent – there is always room for improvement! I have noticed several errors in your notes, including…

10. It is great that you are trying your best, but don’t stop here – keep pushing yourself to get even better results. It would be good to see you editing your work to remove the small errors creeping into your work…

11. You have put in a lot of hard work, and it is starting to show. One area for improvement is your tone of voice, which sometimes comes across too soft. Don’t be afraid to project your voice next time.

12. You are making good progress, but don’t forget to focus on your weaknesses too. One weakness to focus on is…

13. Your efforts are commendable, but it would have been good to have seen you focus throughout as your performance waned towards the end of the session.

15. While your work is good, I feel you are becoming complacent – keep looking for ways to improve. For example, it would be good to see you concentrating harder on providing critique of the ideas explored in the class.

16. It is great that you are trying your best, but don’t stop here – keep pushing yourself to get even better results! Try to improve your handwriting by slowing down and focusing on every single letter.

17. You have put in a lot of hard work, and it is starting to show. Keep up the good work and you will see your grades slowly grow more and more. I’d like to see you improving your vocabulary for future pieces.

18. You are making good progress, but don’t forget to focus on your weaknesses too. One weakness to focus on is…

19. You have potential and should work on your using more appropriate sources to achieve better outcomes. As a next step, it is a good idea to…

Constructive Feedback for an Essay

1. Your writing style is good but you need to use more academic references in your paragraphs.

2. While you have reached the required word count, it would be good to focus on making sure every paragraph addresses the essay question.

3. You have a good structure for your essay, but you could improve your grammar and spelling.

4. You have made some good points, but you could develop them further by using more examples.

5. Your essay is well-written, but it would be helpful to provide more analysis of the topic.

6. You have answered the question well, but you could improve your writing style by being more concise.

7. Excellent job! You have covered all the key points and your writing is clear and concise.

8. There are a few errors in your essay, but overall it is well-written and easy to understand.

9. There are some mistakes in terms of grammar and spelling, but you have some good ideas worth expanding on.

10. Your essay is well-written, but it needs more development in terms of academic research and evidence.

11. You have done a great job with what you wrote, but you missed a key part of the essay question.

12. The examples you used were interesting, but you could have elaborated more on their relevance to the essay.

13. There are a few errors in terms of grammar and spelling, but your essay is overall well-constructed.

14. Your essay is easy to understand and covers all the key points, but you could use more evaluative language to strengthen your argument.

15. You have provided a good thesis statement , but the examples seem overly theoretical. Are there some practical examples that you could provide?

Constructive Feedback for Student Reports

1. You have worked very hard this semester. Next semester, work on being more consistent with your homework.

2. You have improved a lot this semester, but you need to focus on not procrastinating.

3. You are doing well in most subjects, but you could improve your grades by paying more attention in class and completing all your homework.

4. You are doing well in most subjects, but you could still improve your grades by studying more and asking for help when you don’t understand something.

5. You have shown great improvement this semester, keep up the good work! However, you might want to focus on improving your test scores by practicing more.

6. You have made some good progress this semester, but you need to continue working hard if you want to get good grades next year when the standards will rise again.

7. Next semester, focus on completing all your homework on time and paying more attention in class.

8. You have worked hard this semester, but you could still improve your grades by taking your time rather than racing through the work.

9. Next semester, focus on completing all your homework in advance so you have time to check it over before submission.

10. While you usually understand the instructions, don’t forget to ask for help when you don’t understand something rather than guessing.

11. You have shown great improvement this semester, but you need to focus some more on being self-motivated rather than relying on me to keep you on task.

Constructive feedback on Homework

1. While most of your homework is great, you missed a few points in your rush to complete it. Next time, slow down and make sure your work is thorough.

2. You put a lot of effort into your homework, and it shows. However, make sure to proofread your work for grammar and spelling mistakes.

3. You did a great job on this assignment, but try to be more concise in your writing for future assignments.

4. This homework is well-done, but you could have benefited from more time spent on research.

5. You have a good understanding of the material, but try to use more examples in your future assignments.

6. You completed the assignment on time and with great accuracy. I noticed you didn’t do the extension tasks. I’d like to see you challenging yourself in the future.

Related Articles

- Examples of Feedback for Teachers

- 75 Formative Assessment Examples

Giving and receiving feedback is an important part of any learning process. All feedback needs to not only grade work, but give advice on next steps so students can learn to be lifelong learners. By providing constructive feedback, we can help our students to iteratively improve over time. It can be challenging to provide useful feedback, but by following the simple guidelines and examples outlined in this article, I hope you can provide comments that are helpful and meaningful.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

2 thoughts on “51 Constructive Feedback Examples for Students”

Very helpful to see so much great developmental feedback with so many different examples.

Great examples of constructive feedback, also has reinforced on the current approach i take.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Response: Ways to Give Effective Feedback on Student Writing

- Share article

This is the second post in a four-part series. You can see Part One here .)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What are the best ways to give students feedback on their writing?

Part One began with responses from Anabel Gonzalez, Sarah Woodard, Kim Jaxon, Ralph Fletcher, Mary Beth Nicklaus, and Leah Wilson. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Anabel, Sarah, and Kim on my BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Today, Susan M. Brookhart, Cheryl Mizerny, Amy Benjamin, Kate Wolfe Maxlow, Karen Sanzo, Andrew Miller, David Campos, and Kathleen Fad share their commentaries.

Response From Susan M. Brookhart

Susan Brookhart, Ph.D., is the author of How to Use Grading to Improve Learning (ASCD 2017) and How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students (2nd edition, ASCD 2017)). She is a professor emeritus at Duquesne University and an author and consultant. Her focus is classroom assessment and its impact on teaching, learning, and motivation:

Giving feedback on writing is a special responsibility. If you ask students to write thoughtfully to you, it would be hypocritical of you not to write (or speak, if your feedback is oral) thoughtfully back to them. And students will notice! Here are five things to keep in mind as you think about feedback on students’ written work:

#1 - Before the students write, make sure they know what they are trying to learn (more specifically than just “writing”) and what qualities their writing should exhibit. Unless students are trying to learn something specific, they will experience teacher feedback as additional teacher directions they have to follow. So, for example, if students are writing descriptive paragraphs, they should know what the kind of descriptive paragraphs they are aiming for looks like. Criteria for success might be that they (1) use adjectives that describe by telling what the object of their description looks, sounds, tastes, smells, or feels like; and (2) help their readers feel like they “are there,” experiencing whatever is described themselves. If this is what students are aiming to do, then the feedback questions are already set up: Are my adjectives descriptive? Do they conjure up sight, sound, taste, smell, or touch? Did you (my teacher and my reader) feel like you really experienced what I was describing, that you were there? The best feedback on student writing tells students what they want to know to get closer to the particular vision of writing they are working on.

#2 - Describe at least one thing the student did well, with reference to the success criteria. Focus your feedback on the criteria, not on other features of the work (like handwriting or grammar, unless that was the focus of the writing lesson). Even the poorest paper has something to commend it. Find that and begin your feedback there. Students can’t navigate toward learning targets by filling in deficits only; they also need to build on their strengths. And don’t assume that just because a student did something well, they know what that is. The best feedback on student writing names and notices where students are meeting criteria that show their learning.

#3 - Suggest the student’s immediate next steps, again with reference to the success criteria. Your feedback does not need to “fix” everything possible. It only needs to take the student’s work to the next level. Select the one or two—whatever is doable in the next draft of the writing piece—things that the student should do next, given where they are right now.The best feedback on student writing moves students forward in their quest to reach a learning goal.

#4 - Make sure you learn something from the feedback episode, too. Too often, teachers think of feedback as their expert advice on students’ writing. But every opportunity to give feedback on student writing is also an opportunity for you to learn something about what your students are thinking, what kinds of writing skills they have, and what they need to learn next. The best feedback on student writing gives teachers a window into student thinking; it doesn’t just advise students.

#5 - Give students an immediate opportunity to use the feedback. Much feedback on student writing is wasted, because students don’t use it. Many teachers subscribe to the myth that students will use the feedback “next time” they write something similar. However, it’s not true that students have some sort of file drawer in their heads, with files labeled according to type of writing, that they will magically open at some point in the future.

No matter how well-intentioned the student, this just isn’t how it works. The best feedback on student writing is followed immediately by a planned opportunity, within instructional time, for students to use the feedback.

Response From Cheryl Mizerny

Cheryl Mizerny has been teaching for more than 20 years, is passionate about middle-level education, and serves on the faculty of the AMLE Leadership Institute. Her practice is guided by her belief in reaching every student and educating the whole child. She currently teaches 6th grade English in Michigan and writes an education blog, “It’s Not Easy Being Tween,” for Middleweb.com:

Good feedback on student writing is time-consuming and takes a great deal of teacher effort, but the results in the improvement of their writing is worth my time. Over the years, I have found some ways to streamline the process.

First, students can’t hit a target they can’t see. Therefore, it is important that they have a clear understanding of the goal of the writing piece. I do lots of front-loading with using mentor texts to study author’s craft. Valuable feedback will tell them how close they are to the target and how they can get closer to a bullseye.

For me, the most important consideration when giving feedback is how likely is this to be used? Whenever possible, my first step is verbal feedback via an individual writing conference during the first draft stage. This lets me correct any major errors before they get too far along. We use Google docs so that they have access to them everywhere, I can see the revision history, and I am able to type my comments right in line with the text (which is faster and neater than my handwriting). Prior to writing my first comments, I have students identify a couple things on which they’d like me to focus when reading their paper. Just as I have goals for the final piece, so should they. Then, I begin the process of reading for feedback.

For me, I’ve found that feedback works best if it meets the following criteria: It’s prompt (not saying it has to be the next day, but students get very upset if they have to wait three weeks to get a draft back and rightly so), conversational and respectful in tone, specifically identifies areas for improvement and prioritizes them, focuses on larger issues such as content over small ones like punctuation, and is strengths-based with a balance of more positive than negative commentary. Feedback such as “Good job” is not helpful nor is “This is way too short.” Students needs specific information about how to make improvements if they are going to do so. If I have an especially weak piece, I don’t provide all the ways it can be improved via written feedback to avoid the child shutting down. That student obviously needs more assistance, and a conference is warranted. I am careful to address only a few areas of improvement per paper and I also comment on the areas in which they have a personal progress goal.

As they begin revising in class, I give some individual time to students to have a conversation about their work. The rest are looking at my comments and addressing each one or reading each other’s work. Prior to them handing in the second draft, I provide a checklist of things to consider and ask students to “whisper-read” to themselves (Google Docs has a screen reader built in) to find simple errors. Once they hand in this draft, I look at their work using a single-point rubric (see Jennifer Gonzalez article ) and make comments on it as a cover sheet. I hand this back without a grade on it. In my experience, once they see a grade, the learning stops. They then have one final pass to make any corrections before I receive the final. We also have a celebration of the writing and share work with one another. In my class, it’s is all about the writing process and not the product and this method works well for us.

Response From Amy Benjamin

Amy Benjamin is a teacher, educational consultant, and author whose most recent book is Big Skills for the Common Core (Routledge). Her website is www.amybenjamin.com :

Recently I asked a group of English and social studies teachers to list the marginal comments that they typically write on their students’ papers. Many of the comments were frowny-faced reprimands ending in exclamation points: “Check spelling! Be specific! Develop! Proofread! Follow directions! Review apostrophe use! Others were milder admonitions, often in the form of questions: Where’s your evidence? This shows what? Is this accurate? Punctuation?” Then there were suggestions that, though valid, are unlikely to do much good: “Be sure to support your claim, support the quote, make an inference, anchor the quote, connect to the question, elaborate meaning of quote, explain detail, review, set up the context for the claim, work on ‘tightening up’ your writing, follow the rubric.” The teacher knows what these comments mean, but do the students? Despite the inordinate amount of time it takes to pore over essays and write these comments, we have reason to suspect that they are not accomplishing their intended purposes, which are twofold: 1) to justify the grade on top of the paper, and 2) to get students to improve their writing. The second is far more important than the first. But if there’s no follow-up to our commentary, then what is the point? What are the best ways to give feedback that actually leads to improvement?

First, let’s consider the tone of our comments: While not all of the comments I collected were negative, most were. Some of the positive ones were “nicely written, well-supported, excellent topic sentence, insightful point, great evidence provided, good intro, good sentence, good use of vocab, love your voice, I love this point.” The best way to keep someone pursuing a challenge is to encourage them. It is not so hard to find something—anything—that merits a pat on the back.

Second, let’s consider the amount of correction that is necessary to foster incremental improvement. Teachers are not copy editors. The copy editor has not done her job unless she has found and fixed every single error . But a teacher’s job should be to point out errors and weaknesses sparingly, staying within what she perceives to be that student’s zone of proximal development. All students are novice writers. Their progress will be recursive. If they take risks to produce increasingly sophisticated language in an academic register, they are likely to make more grammatical mistakes, not fewer. One positive and one negative comment or correction on a student’s paper is probably sufficient to keep the writer on a learning curve.

Think of a child learning to play the saxophone. The child has practiced and plays the rehearsed piece for her weekly lesson. Imagine a music teacher responding like this: “I heard two squeaks, one wrong note, an underplayed dynamic at Letter C, a missed quarter rest on the fourth measure, and you completely ignored the dynamics. Watch your fingering, your breathing, and your posture. Pay attention to the time signature. While you’re at it, give it some feeling. It’s supposed to sound like music, not noise.”

And, third, consider the follow-up. Rubrics are excellent tools because they establish criteria for success and help students self-monitor. But the rubric has to be written in student-friendly language. With an accessible rubric, the student can chart her progress from one piece of writing to another. You can follow-up on a writing assignment with mini-lessons, using authentic sentences from student writing as models of good writing, not only deficient writing.

If you’d like students to take real responsibility for their own writing growth, you may be interested in a resource that I’ve created called RxEdit and RxRevise. There you will find a collection of DIY lessons keyed to various writing needs. You can refer students to these lessons on an as-needed basis. It’s a great way to differentiate instruction. RxEdit and RxRevise are available for free on my website .

Response From Kate Wolfe Maxlow & Karen Sanzo

Kate Wolfe Maxlow and Karen Sanzo’s are co-authors of 20 Formative Assessment Strategies that Work: A Guide Across Content and Grade Levels . Kate Wolfe Maxlow is the Professional Learning Coordinator at Hampton City Schools and Karen Sanzo is a professor of Educational Foundations and Leadership at Old Dominion University:

How many times in school did you write something that made perfect sense to you only to have your teacher or professor write a big, red question mark next to it? The purpose of writing is to communicate thoughts and ideas to an audience, but because the writer cannot simultaneously be both the author and the audience, young writers often require a great deal of feedback in order to learn how to write clearly for an intended audience. Therefore, it is immensely important that teachers provide quality, frequent feedback to students on their writing.

To this end, it is also important to remember that the role of the teacher is to help students improve, not necessarily to expect a perfect product. Marzano (2017) explains that educators “should view learning as a constructive process in which students constantly update their knowledge.” Likewise, Hattie (2017) emphasizes the importance of helping students to engage in metacognitive strategies, such as Planning and Prediction, Elaboration and Organization, and Evaluation and Reflection. When we think of writing as a constructive process in which we should help students engage in metacognitive strategies, we realize how crucial it is that we provide students with feedback throughout the entire writing process, not simply at the end.

What does this look like? Imagine that you give students the following prompt: Explain why we remember George Washington today. Before students begin to write, have them make a plan that includes how they will conduct research, what questions they will ask, and how they will record answers. Check in with each student and then—this is key—provide feedback on their plans. As students begin to implement their plan and conduct research, collect information, and outline their paper, provide feedback on that, too.

What form does that feedback take? Well, whether it’s electronic (such as using Google Docs), verbal, or written doesn’t matter as much as the kind of thinking that the teacher asks the student to do when providing the feedback. For instance, a student has to do less work and actually learns less when a teacher writes, “George Washington did not have wooden teeth,” than if the teacher writes, “Can you find other sources that confirm that George Washington had wooden teeth?” or even “George Washington’s teeth are indeed an interesting subject; do you think we would remember him even if he had his own teeth based on his other accomplishments? What are the biggest reasons we remember him today?”

Feedback can, of course, also concern writing style. If feedback is too prescribed, we cheat students out of critical- and creative-thinking opportunities; if it is too vague, we risk frustrating them. For instance, instead of simply writing, “Vary your sentence style,” when a student starts each sentence in a paragraph with, “We remember George Washington because...,” a teacher could ask, “How can you start each sentence differently in this paragraph to keep the reader’s attention?” This points students in the right direction and also helps them understand why the change is important.

Lastly, while it’s important to give students feedback on their writing, feedback works best when we also collect it from students (Hattie, 2009). The more we ask students to self-evaluate and reflect on their work, the greater the impact on their achievement (Hattie, 2017). To that end, it can work well to have students first self-evaluate their writing using the rubric then come to a writing conference prepared with examples of what’s working in their paper and where they need help. When we give feedback like this, we encourage students not only to become better writers, but better thinkers as well.

Hattie, J (2009). Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York: Routledge

Hattie, J. (2017). Hattie’s 2017 updated list of factors influencing student achievement. Retrieved from https://www.visiblelearningplus.com/sites/default/files/250%20Influences.pdf

Marzano (2017). The New Art and Science of Teaching. Bloomington, IN: ASCD & Solution Tree Press.

Response From Andrew Miller

Andrew Miller is currently an instructional coach at the Shanghai American School in China. He also serves on the National Faculty for the Buck Institute for Education and ASCD, where he consults on a variety of topics. He has worked with educators in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Australia, Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, the Philippines, China, Japan, Indonesia, India, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and the Dominican Republic:

Because we care about our students, we often do two things wrong: We give too much feedback or we tell students the answer in the feedback. Too much feedback is often ground in the traditional “final draft” way of writing, where the teacher collects the papers and then spends hours marking and providing written feedback near the end of the unit and close to when the assignment is due. This is often too much for students to process and/or can be too late. “Why didn’t you tell me my opening paragraph needed work when I wrote it a week ago?” Instead, teachers should provide feedback in smaller chunks in a more ongoing way. This makes the feedback manageable and timely.

For the second problem, teachers should focus on prompting and asking good questions to probe student thinking in the feedback they write. Instead of correcting a large amount of punctuation errors for students, write: “I’m noticing errors in comma and other punctuation usage in your second paragraph.” Here, the student must seek out those errors and correct them. They must learn! If the teacher does all the corrections for the students, then that teacher has done all the thinking for the student. In fact, it may have robbed that student of an opportunity to learn. Feedback should cause students to think and learn, not give away all the answers.

One final rule—don’t give feedback unless you can devote time for students to use and process it. We’ve all made the mistakes where we give feedback on the summative assessment and then students don’t use it. This is because we have indicated to them that it is summative and it is too late to improve. Teachers waste their time, and students don’t find value in the feedback.

Response From David Campos & Kathleen Fad

David Campos, Ph.D., is a professor of education at the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio, Texas, where he teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in special education, multicultural education, and instructional design and delivery. He has written books on LGBT youth, childhood health and wellness, and the schooling of Latinos. He has co-authored two books with Kathleen Fad: Tools for Teaching Writing (ASCD 2014) and Practical Ideas That Really Work for English Language Learners (Pro-Ed).

Kathleen Fad, Ph.D., is an author and consultant whose professional experience has spanned more than 30 years as a general education teacher, special education teacher, and university professor. Kathy’s specialty is designing practical, common-sense strategies that are research-based:

We also consider the idea of giving feedback from the special education perspective, and, that is, giving feedback so that it is individualized. Our experiences have taught us that in any given classroom, many students may struggle with the same writing issues, but most will have unique difficulties with their writing.

To help teachers give effective feedback on student writing, we created an evaluation protocol based on eight writing traits (in Tools for Teaching Writing, ASCD). Teachers can use this protocol to isolate the areas of writing that individual students struggle with the most. We identified qualities associated with each trait, which provides the teacher with a common language to use when she conferences with individual students.

Teachers can similarly create their own evaluation measure that has qualities associated with the traits or conventions of writing they address in their lessons. For example, teachers can ask themselves, “How does good presentation manifest in student writing?” Then, they can work toward developing the qualities of presentation they can regularly use in their instruction and student feedback. The key to effective feedback is to give students concrete qualities about the writing trait or convention and use those regularly in their conferences with students.

After teachers have developed this common language about writing, students can learn to self-reflect on their work. As a way of giving feedback, teachers can provide students with checklists associated with the qualities of the trait and have the students self-reflect or review their peers’ writing.

Thanks to Susan, Cheryl, Amy, Kate, Karen, Andrew, David, and Kathleen for their contributions.

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder—you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And if you missed any of the highlights from the first seven years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. The list doesn’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Race & Gender Challenges

Classroom Management Advice

Best Ways to Begin The School Year

Best Ways to End The School Year

Implementing the Common Core

Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

Teaching Social Studies

Project-Based Learning

Using Tech in the Classroom

Parent Engagement in Schools

Teaching English-Language Learners

Reading Instruction

Writing Instruction

Education Policy Issues

Student Assessment

Differentiating Instruction

Math Instruction

Science Instruction

Advice for New Teachers

Author Interviews

Entering the Teaching Profession

The Inclusive Classroom

Learning & the Brain

Administrator Leadership

Teacher Leadership

Relationships in Schools

Professional Development

Instructional Strategies

Best of Classroom Q&A

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributers to this column .

Look for Part Three in a few days.

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

5 effective constructive feedback examples: Unlocking student potential

This video provides an overview of the key features instructors need to know to make best use of Feedback Studio, accessed through the Turnitin website.

At Turnitin, we’re continuing to develop our solutions to ease the burden of assessment on instructors and empower students to meet their learning goals. Turnitin Feedback Studio and Gradescope provide best-in-class tools to support different assessment types and pedagogies, but when used in tandem can provide a comprehensive assessment solution flexible enough to be used across any institution.

By completing this form, you agree to Turnitin's Privacy Policy . Turnitin uses the information you provide to contact you with relevant information. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

Providing constructive feedback examples to students is an important part of the learning journey and is crucial to student improvement. It can be used to feed a student’s love of learning and help build a strong student-teacher relationship. But it can be difficult to balance the “constructive” with the “feedback” in an effective way.

On one hand, we risk the student not absorbing the information, and therefore missing an opportunity for growth when we offer criticism, even when constructive. On the other hand, there is a risk of discouraging the student, dampening their desire to learn, or even harming their self-confidence. Further complicating the matter is the fact that every student learns differently, hears and absorbs feedback differently, and is at a different level of emotional and intellectual development than their peers.

We know that we can’t teach every student the exact same way and expect the same results for each of them; the same holds true for providing constructive feedback examples. For best results, it’s important to tailor how constructive feedback is provided based on content, student needs, and a variety of other factors.

In this blog, we’ll take a look at constructive feedback examples and the value of effective instructor feedback, centering on Dr. John Hattie’s research on “Where to next?” feedback. We’ll also offer key examples for students, so instructors at different grade levels can apply best practices right away.

In 1992 , Dr. John Hattie—in a meta-analysis of multiple scientific studies—found that “feedback has one of the positive influences on student achievement,” building on Sadler’s concept that good feedback can close the gap between where students are and where they aim to be (Sadler, 1989 ).

But before getting too far into specifics, it would be helpful to talk about what “constructive feedback” is. Not everyone will define it in quite the same way — indeed, there is no singular accepted definition of the phrase.

For example, a researcher in Buenos Aires, Argentina who studies medical school student and resident performance, defines it, rather dryly, as “the act of giving information to a student or resident through the description of their performance in an observed clinical situation.” In workplace scenarios , you’ll often hear it described as feedback that “reinforces desired behaviors” or, a definition that is closer to educators’ goals in the classroom, “a supportive way to improve areas of opportunity.”

Hattie and Clarke ( 2019 ) define feedback as the information about a learning task that helps students understand what is aimed to be understood versus what is being understood.

For the purposes of this discussion, a good definition of constructive feedback is any feedback that the giver provides with the intention of producing a positive result. This working definition includes important parts from other, varied definitions. In educational spaces, “positive result” usually means growth, improvement, or a lesson learned. This is typically accomplished by including clear learning goals and success criteria within the feedback, motivating students towards completing the task.

If you read this header and thought “well… always?” — yes. In an ideal world, all feedback would be constructive feedback.

Of course, the actual answer is: as soon, and as often, as possible.

Learners benefit most from reinforcement that's delivered regularly. This is true for learners of all ages but is particularly so for younger students. It's best for them to receive constructive feedback as regularly, and quickly, as possible. Study after study — such as this one by Indiana University researchers — shows that student information retention, understanding of tasks, and learning outcomes increase when they receive constructive feedback examples soon after the learning moment.

There is, of course, some debate as to precise timing, as to how soon is soon enough. Carnegie Mellon University has been using their proprietary math software, Cognitive Tutor , since the mid-90s. The program gives students immediate feedback on math problems — the university reports that students who use Cognitive Tutor perform better on a variety of assessments , including standardized exams, than their peers who haven’t.

By contrast, a study by Duke University and the University of Texas El Paso found that students who received feedback after a one-week delay retained new knowledge more effectively than students who received feedback immediately. Interestingly, despite better performance, students in the one-week delayed feedback group reported a preference for immediate feedback, revealing a metacognitive disconnect between actual and perceived effectiveness. Could the week delay have allowed for space between the emotionality of test-taking day and the calm, open-to-feedback mental state of post-assessment? Or perhaps the feedback one week later came in greater detail and with a more personalized approach than instant, general commentary? With that in mind, it's important to note that this study looked at one week following an assessment, not feedback that was given several weeks or months after the exam, which is to say: it may behoove instructors to consider a general window—from immediate to one/two weeks out—after one assessment and before the next assessment for the most effective constructive feedback.

The quality of feedback, as mentioned above, can also influence what is well absorbed and what is not. If an instructor can offer nuanced, actionable feedback tailored to specific students, then there is a likelihood that those students will receive and apply that constructive feedback more readily, no matter if that feedback is given minutes or days after an assessment.

Constructive feedback is effective because it positively influences actions students are able to take to improve their own work. And quick feedback works within student workflows because they have the information they need in time to prepare for the next assessment.

No teacher needs a study to tell them that motivated, positive, and supported students succeed, while those that are frustrated, discouraged, or defeated tend to struggle. That said, there are plenty of studies to point to as reference — this 2007 study review and this study from 2010 are good examples — that show exactly that.

How instructors provide feedback to students can have a big impact on whether they are positive and motivated or discouraged and frustrated. In short, constructive feedback sets the stage for effective learning by giving students the chance to take ownership of their own growth and progress.

It’s one thing to know what constructive feedback is and to understand its importance. Actually giving it to students, in a helpful and productive way, is entirely another. Let’s dive into a few elements of successful constructive feedback:

When it comes to providing constructive feedback that students can act on, instructors need to be specific.

Telling a student “good job!” can build them up, but it’s vague — a student may be left wondering which part of an assessment they did good on, or why “good” as opposed to “great” or “excellent” . There are a variety of ways to go beyond “Good job!” on feedback.

On the other side of the coin, a note such as “needs work” is equally as vague — which part needs work, and how much? And as a negative comment (the opposite of constructive feedback), we risk frustrating them or hurting their confidence.

Science backs up the idea that specificity is important . As much as possible, educators should be taking the time to provide student-specific feedback directly to them in a one-on-one way.

There is a substantial need to craft constructive feedback examples in a way that they actively address students’ individual learning goals. If a student understands how the feedback they are receiving will help them progress toward their goal, they’re more likely to absorb it.

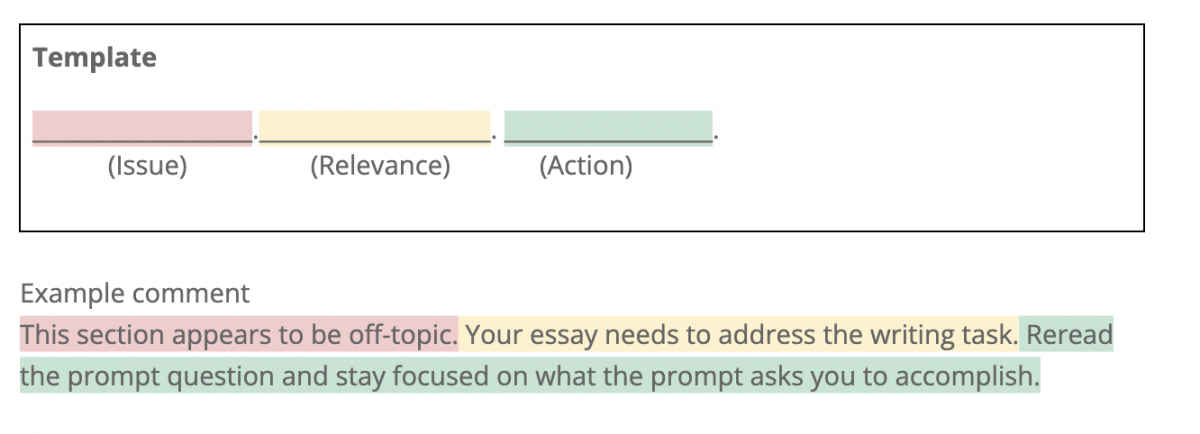

Our veteran Turnitin team of educators worked directly with Dr. John Hattie to research the impact of “Where to next?” feedback , a powerful equation for goal-oriented constructive feedback that—when applied formatively and thoughtfully—has been shown to dramatically improve learning outcomes. Students are more likely to revise their writing when instructors include the following three essential components in their feedback:

- Issue: Highlighting and clearly describing the specific issue related to the writing task.

- Relevance: Aligning feedback explicitly to the stated expectations of the assignment (i.e. rubric).

- Action: Providing the learner with their “next steps,” appropriately guiding the work, but not giving away the answer.

It’s also worth noting that quality feedback does not give the answer outright to the student; rather, it offers guidelines and boundaries so the students themselves can do their own thinking, reasoning, and application of their learning.

As mentioned earlier, it's hard to balance the “constructive” with the “feedback” in an effective way. It’s hard, but it’s important that instructors learn how to do it, because how feedback is presented to a student can have a major impact on how they receive it .

Does the student struggle with self confidence? It might be helpful to precede the corrective part of the feedback acknowledging something they did well. Does their performance suffer when they think they’re being watched? It might be important not to overwhelm them with a long list of ideas on what they could improve.

Constructive feedback examples, while cued into the learning goals and assignment criteria, also benefit from being tailored to both how students learn best and their emotional needs. And it goes without saying that feedback looks different at different stages in the journey, when considering the age of the students, the subject area, the point of time in the term or curriculum, etc.

In keeping everything mentioned above in mind, let’s dive into five different ways an instructor could give constructive feedback to a student. Below, we’ll look at varying scenarios in which the “Where to next?” feedback structure could be applied. Keep in mind that feedback is all the more powerful when directly applied to rubrics or assignment expectations to which students can directly refer.

Below is the template that can be used for feedback. Again, an instructor may also choose to couple the sentences below with an encouraging remark before or after, like: "It's clear you are working hard to add descriptive words to your body paragraphs" or "I can tell that you conducted in-depth research for this particular section."

For instructors with a pile of essays needing feedback and marks, it can feel overwhelming to offer meaningful comments on each one. One tip is to focus on one thing at a time (structure, grammar, punctuation), instead of trying to address each and every issue. This makes feedback not only more manageable from an instructor’s point of view, but also more digestible from a student’ s perspective.

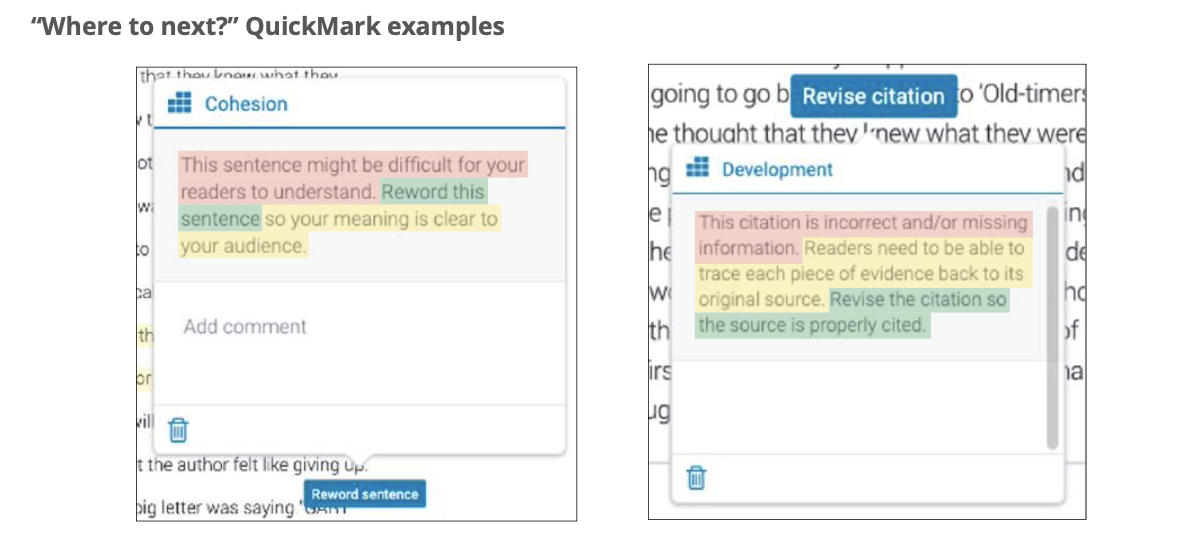

Example: This sentence might be difficult for your readers to understand. Reword this sentence so your meaning is clear to your audience.

Rubrics are an integral piece of the learning journey because they communicate an assignment’s expectations to students. When rubrics are meaningfully tied to a project, it is clear to both instructors and students how an assignment can be completed at the highest level. Constructive feedback can then tie directly to the rubric , connecting what a student may be missing to the overarching goals of the assignment.

Example: The rubric requires at least three citations in this paper. Consider integrating additional citations in this section so that your audience understands how your perspective on the topic fits in with current research.

Within Turnitin Feedback Studio, instructors can add an existing rubric , modify an existing rubric in your account, or create a new rubric for each new assignment.

QuickMark comments are sets of comments for educators to easily leave feedback on student work within Turnitin Feedback Studio.

Educators may either use the numerous QuickMarks sets readily available in Turnitin Feedback Studio, or they may create sets of commonly used comments on their own. Regardless, as a method for leaving feedback, QuickMarks are ideal for leaving “Where to next?” feedback on student work.

Here is an example of “Where to next?” feedback in QuickMarks:

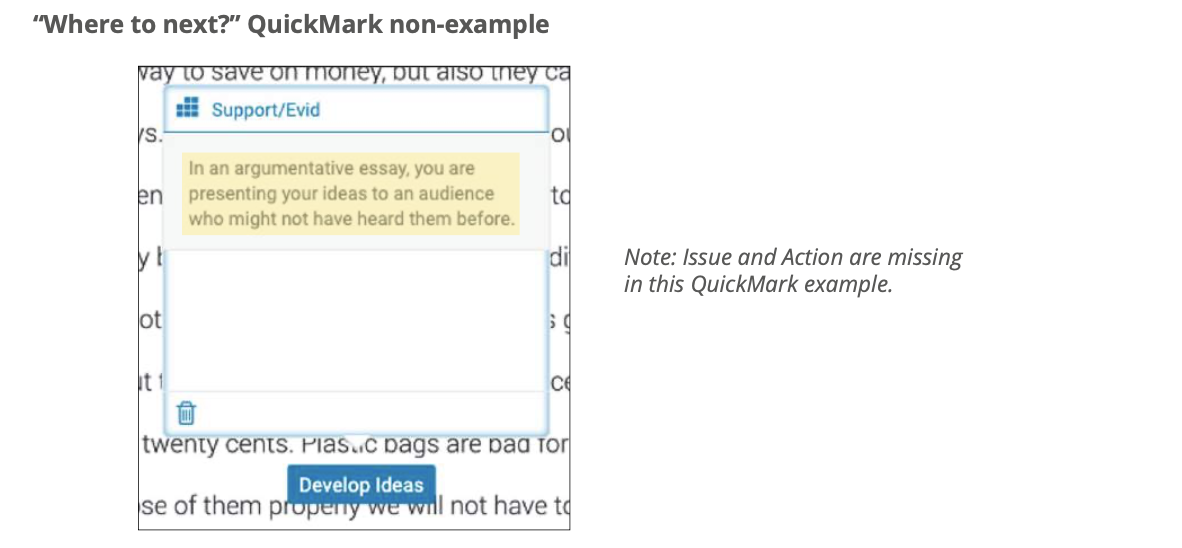

It can be just as helpful to see a non-example of “Where to next?” feedback. In the image below, a well-meaning instructor offers feedback to a student, reminding them of what type of evidence is required in an argumentative essay. However, Issue and Action are missing, which leaves the student wondering: “Where exactly do I need to improve my support? And what next steps ought to be taken?”

Here is a non-example of “Where to next?” feedback in QuickMarks:

As an instructor in a STEM class, one might be wondering, “How do I apply this structure to my feedback?” While “Where to next?” feedback is most readily applied to English Language Arts/writing course assignments, instructors across subject areas can and should try to implement this type of feedback on their assignments by following the structure: Issue + Relevance + Action. Below is an example of how you might apply this constructive feedback structure to a Computer Science project:

Example: The rubric asks you to avoid “hard coding” values, where possible. In this line, consider if you can find a way to reference the size of the array instead.

As educators, we have an incredible power: the power to help struggling students improve, and the power to help propel excelling students on to ever greater heights.

This power lies in how we provide feedback. If our feedback is negative, punitive, or vague, our students will suffer for it. But if it's clear, concise, and, most importantly, constructive feedback, it can help students to learn and succeed.

Study after study have highlighted the importance of giving students constructive feedback, and giving it to them relatively quickly. The sooner we can give them feedback, the fresher the information is in their minds. The more constructively that we package that feedback, the more likely they are to be open to receiving it. And the more regularly that we provide constructive feedback examples, the more likely they are to absorb those lessons and prepare for the next assessment.

The significance of providing effective constructive feedback to students cannot be overstated. By offering specific, actionable insights, educators foster a sense of self-improvement and can truly help to propel students toward their full potential.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Learning

- Home ›

- Resource Library

Teaching Strategies |

Giving Effective Feedback on Student Writing

Author: Amanda Leary

By focusing on providing quality, effective feedback, we can maximize its positive effects on learning—not only helping students become better writers, but better thinkers, with increased confidence and motivation to succeed.

Providing feedback is one of the most critical tasks of teaching. Well-balanced feedback, addressing both achievements and areas for improvement, can help students develop new skills, reinforce their learning, and boost their academic confidence. Ineffective feedback, however, can compound students’ low motivation and self-perception, hindering their development and learning (Wingate, 2010). Good feedback does much more than correct errors; it’s an opportunity to empower and affirm students as knowledge makers, to improve their self-awareness, and to develop strategies for improvement now and in their future work.

By focusing on providing quality, effective feedback, we can maximize its positive effects on learning—not only helping students become better writers, but better thinkers, with increased confidence and motivation to succeed. This doesn’t happen in a vacuum, however; feedback isn’t useful for students if they don’t understand or know how to incorporate it.

Deciding what and how much to comment on will depend on your particular disciplinary, class, and assignment context. The strategies below will help you determine what kind of feedback to give and when, as well as identify potential next steps for helping students actually use your feedback.

Preparing to Give Feedback

Before you ever read the first paper, there are a few key questions to ask yourself that can help save a lot of time and make your feedback more effective: 1) why are you giving feedback , and 2) what are you looking for? Let’s take these in turn.

Why are you giving feedback?

Depending on when in the writing process you’re providing students with feedback, your comments will serve different purposes. Just as assignments can be either formative or summative , so, too, can your feedback. Summative feedback addresses what students did well or poorly at one particular instance and is often used in evaluation to justify a grade, whereas formative feedback often answers, “What can I do to improve next time?” While formative feedback often aligns with formative assignments, such as drafts and other process work such as proposals and outlines, you can also provide formative feedback on final, summative assignments and vice versa. We often switch between these two types of feedback on a single assignment, so taking time to establish beforehand what the goal of giving feedback is will focus the kinds of comments you make. It might be helpful for students to use markers in your comments to clearly distinguish between “this time” and “next time” feedback.

Another way to distinguish the two is in your mindset toward the task of giving feedback: are you a coach or a grader? If you’re approaching student work with the sole purpose of attaching a grade, then your feedback is likely to be more summative—feeding back to the writing. The mindset of a reader, however, is more aligned with a developmental approach giving more formative feedback. Here, we might think more in terms of feeding forward —concentrating our attention on actionable steps students can take to continue to improve their writing.

What are you looking for?

Sometimes, the hardest part about giving feedback can be deciding where to start. We know good writing when we see it; however, articulating those features of good writing into clearly defined criteria for a successful assignment can help mitigate the feeling that you need to comment on every feature or correct every mistake you see. Providing these criteria to students in advance has demonstrable benefits for their learning and can improve the quality of their assignments (Brookhart, 2018). Criteria should be aligned with the goals you have for the assignment, the overall goals of your course, and targeted at students at the appropriate level (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

As you’re developing your criteria, you may find it helpful to prioritize your higher-order and lower-order concerns . Higher-order concerns will be more closely aligned with your goals for the assignment. For example, if you are providing feedback on a seminar paper, your higher-order concerns may be related to how well students demonstrated their understanding of a particular set of readings through a clearly articulated thesis and synthesis of primary and secondary sources. Lower-order concerns, such as sentence structure and grammar, would not feature as heavily in your feedback except where they affect the readability of the writing. However, if teaching specific writing skills was the primary focus of your class, your higher-order concerns might include sentence structure or grammatical understanding. Knowing what your priorities are for students’ writing before you sit down with the first assignment will keep your feedback targeted to your high-priority criteria rather than noting every little detail, resulting in fewer comments—which can be overwhelming for both you and students.

Taking the time to identify why you’re giving feedback and what your priorities are for students’ writing keeps your comments focused and relevant to students.

While You’re Responding to Student Work

Whether formative or summative, your feedback should be specific , actionable , focused on patterns , and balanced . The following tips will help you not only save time commenting, but will also ensure your comments are useful to students:

- Be specific: Simply underlining, using exclamation marks, or the infamous “awkward” doesn’t tell students anything about how to revise their essay. Highlight strengths and weaknesses in reference to specific passages and examples and offer concrete, actionable suggestions for improvement.

- Focus on action: If students don’t understand your comments, they can’t use them (Chanock, 2000; Lea and Steirer, 2000). We may know what periodic and loose sentences are, or maybe we wrote our dissertation on that niche author that would really round out a students’ discussion of a topic. Writing “comma splice” or “what about the kinematics of root growth” in the margins without explaining what that is or why it matters for their writing (especially if it isn’t connected to what you’ve taught in class) isn’t actionable feedback.

- Look for patterns: There are likely to be several mistakes repeated within and across students’ writing. Keep a comment back of feedback addressing common mechanical mistakes; rather than re-writing the same comment on every paper, you can note the first instance with an explanatory comment that applies across students. Over time, you might also develop a repository of recurring comments on more structural or content-based patterns, such as thesis development, structure and organization, or use of quotes and evidence. Having stock language on hand that you can then tailor to a student’s particular essay can help save time. Where you see the same mistake being repeated across student work, you can include a more general comment about the issue with a note that more information will be provided in class.

- Balance praise and critique: The most effective feedback contains a balance of challenge and support (Lizzio and Wilson, 2008). This doesn’t mean, however, that we should feel compelled to use the “feedback sandwich”: placing critical feedback between moments of praise. Students can recognize and discount token positive comments (Hyland and Hyland, 2001), so rather than sandwiching feedback, give valid criticism while offering encouragement, genuine appreciation for student writing, and belief in students’ ability to succeed.

Applying Feedback

Giving feedback is just one part of the process; it is equally important for students to be active participants if learning is to happen (Winstone et al., 2017). Depending on the context of your course, you might facilitate student engagement with feedback in class or through assignments that promote reflection on the writing process:

- Use class time to address feedback that applies to many students’ work. Provide instruction or resources for how students can integrate that feedback into their writing with an opportunity to practice.

- Where time allows, incorporate writing days into your course calendar as a dedicated opportunity for students to work through your feedback as they revise their assignments.

- Try a reflective feedback journal as a space for students to reflect on their immediate reactions to your comments and how they plan to address them. This could be done in class or as part of an ongoing journal throughout the course.

- Incorporate peer review as a mechanism for understanding feedback and to empower students to further self-assess their own work (McConlogue, 2020; Huisman et al., 2019).

- Add a brief metacognitive cover letter or memo to final assignments that asks students to reflect on how they incorporated feedback from rough to final draft.

Integrating these strategies into your practice will not only save you time, but help keep your feedback targeted, educative, and effective. Viewing feedback as a dialogic process that begins before you make your first comment and involves students as active recipients of that feedback is an important part of giving students comments they can—and actually want to—use.

Brookhart, Susan M. “Appropriate Criteria: Key to Effective Rubrics.” Frontiers in Education 3 (2018).

Chanock, Kate. “Comments on Essays: Do Students Understand What Tutors Write?” Teaching in Higher Education 5, no. 1 (2000): 95–105.

Hattie, John, and Helen Timperley. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 77, no. 1 (2007): 81–112.

Huisman, Bart, Nadira Saab, Paul van den Broek, and Jan van Driel. “The Impact of Formative Peer Feedback on Higher Education Students' Academic Writing: a Meta-Analysis.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 44, no. 6 (2019): 863–80.

Hyland, Fiona, and Ken Hyland. “Sugaring the Pill: Praise and Criticism in Written Feedback.” Journal of Second Language Writing 10, no. 3 (2001): 185–212.

Lea, M. R. and Steirer, B. (eds). Student Writing in Higher Education: New Contexts . Buckingham: Open University Press, 2000.

Lizzio, Alf, and Keithia Wilson. “Feedback on Assessment: Students’ Perceptions of Quality and Effectiveness.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 33, no. 3 (2008): 263–75.

McConlogue, Teresa. Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education: A Guide for Teachers . UCL Press. 1st ed. London: UCL Press, 2020.

Wingate, Ursula. “The Impact of Formative Feedback on the Development of Academic Writing.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 35, no. 5 (2010): 519–33.

Winstone, Naomi E., Robert A. Nash, James Rowntree, and Michael Parker. “‘It’d Be Useful, but I Wouldn’t Use It’: Barriers to University Students’ Feedback Seeking and Recipience.” Studies in Higher Education (Dorchester-on-Thames) 42, no. 11 (2017): 2026–41.

How to Give Positive Feedback on Student Writing

If your corrective feedback is very detailed but your positive comments are quick and vague, you may appreciate this advice from teachers across the country.

Your content has been saved!

“Nice work.” “Great job.” “Powerful sentence.” Even though I knew they wouldn’t mean much to students, these vague and ineffective comments made their way into my writing feedback recently. As I watched myself typing them, I knew I was in a rut. My critical comments, on the other hand, were lengthy and detailed. Suggestions and corrections abounded. I realized that I was focused too much on correcting student work and not enough on the goal of giving rich positive feedback.

As a writer, I know how hard it is when the negative feedback outweighs the positive. We all have things to work on, but focusing only on what to fix makes it hard to feel that our skills are seen and appreciated. My students put so much work into their writing, and they deserve more than my two-word positive sentences.

I wanted out of the rut, so I turned to my favorite professional network—teacher Twitter—and asked for help . “What are your favorite positive comments to make about student writing?” I asked. Here are some of the amazing responses and the themes that emerged from more than 100 replies from teachers.

Give a Window Into Your Experience as the Reader

Students typically can’t see us while we’re experiencing their writing. One genre of powerful positive comments: insights that help students understand how we responded as readers. Teacher Amy Ludwig VanDerwater shared these sentence stems, explaining that “commenting on our reading experience before the craft of writing is a gift”:

On a similar note, Virginia S. Wood shared: “I will tell them if I smiled, laughed, nodded my head, pumped my fist while reading their work, and I’ll tell them exactly where and why.”

I used Wood’s advice recently when I looked through a student’s project draft that delighted me. I wrote to her, “I have the biggest smile on my face right now. This is such an awesome start.”

Giving students insight into our experience as readers helps to connect the social and emotional elements of writing. Positive comments highlighting our reading experience can encourage students to think about their audience more intentionally as they write.

Recognize Author’s Craft and Choices

Effective feedback can also honor a student’s voice and skills as a writer. Pointing out the choices and writing moves that students make helps them feel that we see and value their efforts. Joel Garza shared, “I avoid ‘I’ statements, which can seem more like a brag about my reading than about their writing.” Garza recommends using “you” statements instead, such as “You crafted X effect so smoothly by...” or “You navigate this topic in such an engaging way, especially by...” and “You chose the perfect tone for this topic because...”

Similarly, seventh-grade teacher Jennifer Leung suggested pointing out these moments in this way: “Skillful example of/use of (transition, example, grammatical structure).” This can also help to reinforce terms, concepts, and writing moves that we go over in class.

Rebekah O’Dell , coauthor of A Teacher’s Guide to Mentor Texts , gave these examples of how we might invoke mentor texts in our feedback:

O’Dell’s advice reinforced the link between reading and writing. Thinking of these skills together helps us set up feedback loops. For example, after a recent close reading activity, I asked students to name one lesson they had learned from the mentor text that they could apply to their own writing. Next time I give writing feedback, I can highlight the places where I see students using these lessons.

Another teacher, Grete Howland , offered a nonjudgmental word choice. “I like to use the word ‘effective’ and then point out, as specifically as I can, why I found something effective. I feel like this steers away from ‘good’/‘bad’ and other somewhat meaningless judgments, and it focuses more on writing as an exchange with a reader.”

Celebrate Growth

Positive feedback supports student progress. Think of positive comments as a boost of momentum that can help students continue to build their identity as writers. Kelly Frazee recommended finding specific examples to help demonstrate growth, as in “This part shows me that you have improved with [insert skill] because compared to last time…” As teachers, we often notice growth in ways that our students may not recognize about themselves. Drawing out specific evidence of growth can help students see their own progress.

Finally, I love this idea from Susan Santone , an instructor at the University of Michigan: When students really knock it out of the park, let them know. Santone suggested, “When my students (college level) nail something profound in a single sentence, I write ‘Tweet!’ ‘Put this onto a T-shirt!’ or ‘Frame this and hang it on a wall!’—in other words, keep it and share it!”

These ideas are all great starting points for giving students meaningful positive feedback on their writing. I’ve already started to use some of them, and I’ve noticed how much richer my feedback is when positive and constructive comments are equally detailed. I’m looking forward to seeing how these shifts propel student writing. Consider trying out one of these strategies with your students’ next drafts.

- Utility Menu

- Writing Center

- Writing Program

- Responding to Student Writing

PRINCIPLES OF RESPONDING TO STUDENT WRITING

Your comments on student writing should clearly reflect the hierarchy of your concerns about the paper. Major issues should be treated more prominently and at greater length; minor issues should be treated briefly or not at all. If you comment extensively on grammatical or mechanical issues, you should expect students to infer that such issues are among your main concerns with the paper. It is after all not unreasonable for students to assume that the amount of ink you spill on an issue bears some relationship to the issue’s importance.

It is often more helpful to comment explicitly, substantively, and in detail about two or three important matters than it is to comment superficially about many issues. Many veteran readers find the experience of responding to student writing to be one of constantly deciding not to comment on less important issues. Such restraint allows you to focus your energies on just a few important points and also tends to yield a cleaner and more easily intelligible message for students.

Some suggestions for writing comments follow.

READING THE PAPER

You may want to skim through four or five papers to get a sense of the pile before reading and grading any single paper. Many instructors read each paper once through to grasp the overall argument before making any marks. Whether skimming on a first time through or reading carefully, you might keep the following categories in mind, which will help you assess the paper’s strengths and weaknesses:

- Thesis: Is there one main argument in the paper? Does it fulfill the assignment? Is the thesis clearly stated near the beginning of the paper? Is it interesting, complex? Is it argued throughout?

- Structure: Is the paper clearly organized? Is it easy to understand the main point of each paragraph? Does the order of the overall argument make sense, and is it easy to follow?

- Evidence and Analysis: Does the paper offer supporting evidence for each of its points?Does the evidence suggest the writer’s knowledge of the subject matter? Has the paper overlooked any obvious or important pieces of evidence? Is there enough analysis of evidence? Is the evidence properly attributed, and is the bibliographical information correct?

- Sources: If appropriate or required, are sources used besides the main text(s) under consideration? Are they introduced in an understandable way? Is their purpose in the argument clear? Do they do more than affirm the writer’s viewpoint or represent a “straw person” for knocking down? Are responsible inferences drawn from them? Are they properly attributed, and is the bibliographical information correct?

- Style: Is the style appropriate for its audience? Is the paper concise and to the point? Are sentences clear and grammatically correct? Are there spelling or proofreading errors?

WRITING A FINAL COMMENT

Y our final comment is your chance not only to critique the paper at hand but also to communicate your expectations about writing and to teach students how to write more effective papers in the future.

The following simple structure will help you present your comments in an organized way:

- Reflect back the paper’s main point. By reflecting back your understanding of the argument, you let the student see that you took the paper seriously. A restatement in your own words will also help you ground your comment. If the paper lacks a thesis, restate the subject area.

- Discuss the essay’s strengths. Even very good writers need to know what they’re doing well so that they can do it again in the future. Remember to give specific examples.

- Discuss the paper’s weaknesses, focusing on large problems first. You don’t have to comment on every little thing that went wrong in a paper. Instead, choose two or three of the most important areas in which the student needs to improve, and present these in order of descending importance. You may find it useful to key these weaknesses to such essay elements as Thesis, Structure, Evidence, and Style. Give specific examples to show the student what you’re seeing. If possible, suggest practical solutions so that the student writer can correct the problems in the next paper.

- Type your final comments if possible. If you handwrite them, write in a straight line (not on an angle or up the side of a page), and avoid writing on the reverse side; instead, append extra sheets as needed. The more readable your comments are, the more seriously your students are likely to take them.

MARGINAL COMMENTS

While carefully reading a paper, you’ll want to make comments in the margins. These comments have two main purposes: to show students that you attentively read the paper and to help students understand the connection between the paper and your final comments. If you tell a student in the final comment that he or she needs more analysis, for example, the student should be able to locate one or more specific sites in the text that you think are lacking.

SOME PRINCIPLES FOR MAKING MARGINAL COMMENTS

- Make some positive comments. “Good point” and “great move here” mean a lot to students, as do fuller indications of your engagement with their writing. Students need to know what works in their writing if they’re to repeat successful strategies and make them a permanent part of their repertoire as writers. They’re also more likely to work hard to improve when given some positive feedback.

- Comment primarily on patterns—representative strengths and weaknesses. Noting patterns (and marking these only once or twice) helps instructors strike a balance between making students wonder whether anyone actually read their essay and overwhelming them with ink. The “pattern” principle applies to grammar and other sentence-level problems, too.

- Write in complete, detailed sentences. Cryptic comments—e.g., “weak thesis,” “more analysis needed,” and “evidence?”—will be incompletely understood by most students, who will wonder, What makes the thesis weak? What does my teacher mean by “analysis”? What about my evidence? Symbols and abbreviations—e.g., “awk” and “?”—are likewise confusing. The more specific and concrete your comments, the more helpful they’ll be to student writers.

- Ask questions. Asking questions in the margins promotes a useful analytical technique while helping students anticipate future readers’ queries.

- Use a respectful tone. Even in the face of fatigue and frustration, it’s important to address students respectfully, as the junior colleagues they are.

- Write legibly (in any ink but red). If students have to struggle to decipher a comment, they probably won’t bother. Red ink will make them feel as if their essay is being corrected rather than responded to.

- Pedagogy Workshops

- Commenting Efficiently

- Designing Essay Assignments

- Vocabulary for Discussing Student Writing

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- HarvardWrites Instructor Toolkit

- Additional Resources for Teaching Fellows

- Center for Teaching Excellence

- Teaching Hub

- Learning Tech

A Guide to Giving Writing Feedback that Sticks

- Joe Fore , Professor

We turn our attention to a more substantive aspect of writing feedback: what and how much to comment on.

The blog posts in this series on feedback have focused mostly on the stylistic and procedural aspects of feedback: how to prime students to receive constructive feedback , how to phrase feedback so it’s received well , and how to provide feedback in different formats for greater efficiency . Now we turn our attention to a more substantive aspect of writing feedback: what and how much to comment on.

Too often, writing instructors feel compelled to point out every issue—however large or small—that we see in a piece of student writing: a weak topic sentence at the start of the paragraph, a flawed use of evidence a few sentences later, a typo in that same sentence, and a citation error at the paragraph’s end. We sometimes measure our feedback’s value by the pound; each mark we make on the page is valuable, and more is better. But, much of the time, feedback fails not because students are getting too little feedback—but, rather, too much (Grearson, 2002).

The reality is that students can only learn so much on one assignment (Enns & Smith, 2015). By trying to force 25 different lessons on students in a single set of comments, there’s a real risk that they’ll actually take away none. Writing too many comments on an assignment also leaves students with no sense of learning priorities; they may not know which issues are most important to focus on (Enquist, 1996; Grearson, 2002). Moreover, inundating students with comments can demoralize them; they may interpret the sea of handwriting or typed comments as a sign that they’re just not cut out to be a writer.

What’s the solution? We, as writing instructors, need to be more realistic about how much feedback our students can absorb. We need to be more intentional and targeted in what we’re commenting on. We must prioritize our feedback to hit the essentials, the key things we want students to take for next time (Grearson, 2002). And we need to focus on quality over quantity in our comments—explaining those few key concepts in thoughtful ways that allow students to take those lessons to heart (Enquist, 1999).

Using these ideas, we can break the process of providing effective writing feedback into three steps:

Before commenting, establish clear feedback priorities.

While commenting, give fewer, more detailed comments that reflect those priorities.

After commenting, provide global comments that summarize how your feedback connects to those priorities.

Let’s discuss each idea, in turn.

BEFORE YOUR REVIEW

1. establish clear feedback goals and priorities..

Before you sit down to review papers, reflect on what you want students to take away from your feedback. What do you want them to think , feel , or do when they review this feedback (Frost, 2016)? This could vary depending on the timing during the semester, level of student, and nature of the assignment.

At the beginning of the semester, it might make more sense to focus on bigger-picture issues like thesis development or large-scale organization. Again, though, that’s not a hard-and-fast rule. For example, if you’re working with first-year college students or students with less writing experience, you might need some focus on writing mechanics or grammatical issues—even at the early stages.

From those goals, it’s also crucial to establish commenting priorities—a checklist of discrete issues that you’re looking for (Enquist, 1999; Grearson, 2002). Importantly, these need to be written down and put in a place where you can refer to them periodically while reviewing papers . By doing so, you’re more likely to stay on track and provide targeted feedback, rather than getting sidetracked or bogged down with numerous, less-important comments.

DURING YOUR REVIEW

2. skim the assignment first..