A. E. Housman (1859-1936): A Life in Brief

Dick sullivan.

[ Victorian Web Home —> Authors —> A. E. Housman —> Works —> Introduction ]

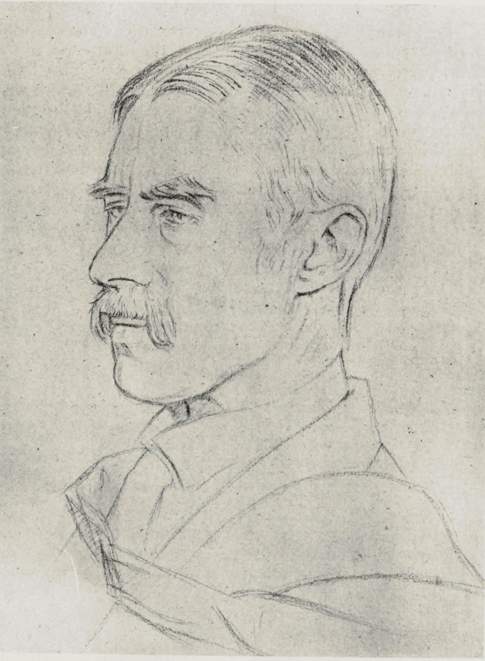

A. E. Housman by William Rothenstein. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

His mother died of cancer on his twelfth birthday: by his thirteenth he was a deist , and a few years later became the atheist he remained all his life. He won a scholarship to St John's College, Oxford. Pater was there, Wilde was in his last term, Jowett was Master of Balliol, Ruskin was visiting professor of art, Hopkins was a priest writing 'Duns Scotus's Oxford' about the 'base and brickish skirt' already encroaching on the town. It was a very Victorian place (apart from Wilde's outrageously coloured knickerbockers) of mutton-chop whiskers, frock coats and stove pipe hats on Sundays.

Housman was already arrogant, already sure he knew what his life's work was to be: redaction — the search for truth through correcting scribal errors in classical texts. He made his name with, among other works, an edition of Manilius, a first-century Roman astronomer whose poetry was poor, his science worse. To Housman, the quality of the book as literature didn't matter. All that did was the accuracy of the text — what did the writer write, how did scribes miscopy it? Redaction was about the defeat of decay. Who did he write for? For the one person, not yet born, with the knowledge and insight to appreciate what he'd done. Perhaps he's still waiting.

At Oxford he also fell in love for the first and only time. Housman was gay. Moses Jackson was not; he was a beefy rowing blue — someone who had earned the equivalent of an American varsity letter — up in Oxford on a science scholarship. Homosexuality he called 'beastliness' or 'spooniness'. And that for Housman meant a lifetime of unfulfilled loneliness.

Because I liked you better Than suits a man to say, It irked you and I promised To throw the thought away. [ More Poems XXXI]

In the year of his Finals, Housman was absorbed in Propertius (a poet who wasn't even in the syllabus), lazed away his time with Jackson (perhaps), was upset by his father's decline and feebleness (maybe) and over-confident (possibly). Certainly he failed Greats.

For the next eleven years he was a clerk in the Patent Office, at first because Moses Jackson also worked there. They shared lodgings till Jackson sailed to India to become the headmaster of a school (he also taught science and even designed the lab furniture). Eighteen months later he came home to marry, but Housman was not asked to the wedding, and in fact knew nothing about it until bride and groom were at sea. They rarely met again. And then never after Jackson retired to British Columbia where he died of cancer in 1922.

Meanwhile, Housman had been making a name for himself in the small world of textual criticism through spare time study in the British Museum. In 1892, on the strength of this scholarship, he was offered the Chair of Latin at University College, London (UCL) .

In 1896, he published A Shropshire Lad , a book of sixty three poems speaking of loss and loneliness, Redcoats, hangings and ale. Larkin called him 'the poet of unhappiness.' Auden complained he was adolescent. Orwell confused him with the class war. His poetry is notable for its simplicity, clarity and brevity — yet there is a depth to it as well. [Housman: Poetry]

Some at UCL said he was scathing yet remote; a man who never troubled to remember the faces of the young women in his classes. At least one student said he never spoke to anybody individually. Others gave different accounts, of course. Who knows? Teachers are there to be caricatured. With staff he was more congenial, even genial, and particularly good at dinner. His idea of a good night out was dinner at the Caf— Royal, a music hall, and supper in the Criterion Grille. Now he had money he became bit of a gastronome and oenophile, holidaying in Paris (for food), Italy (for culture).

If you'd asked Housman the great Socratic question: 'How should we live?' he'd have replied: 'Through knowledge for its own sake, curiosity, the craving to know things as they really are.' Truth was paramount and was to be found in exact knowledge, though mankind had only a faint sense of it. Somewhere hidden in the errors of a classical text was the truth, the words the poet had written. To find them again was to right a kind of wrong done against the truth. The Tree of Knowledge will make us wise, he argued, because our natures need knowledge to be fulfilled.

In 1911 he became Kennedy Professor of Latin in Cambridge, and a fellow of Trinity College. At high table he could dine with seven Nobel Laureates, four presidents of the Royal Society, the philosophers Whitehead, Russell, Wittgenstein, as well as Rutherford who split the atom, and the man who discovered argon. Gide was a guest, and Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas.

In August 1914 the Great War broke out. It's hard to know what to make of Housman's attitude. At the outbreak of war he gave most of his money to the Exchequer. But then he seems to have largely ignored wounded men and soldiers under orders for the Front, when Trinity was half-converted into a hospital and barracks. He did contribute verses to The Blunderbuss , a magazine produced by troops billeted there, but it was a tinkling 1890s piece ( Last Poems II) wholly out of keeping with what was going on in Flanders. In 1915 he holidayed on the Riviera because, he said, the usual appalling people weren't there. But in 1916 he refused to make the tedious crossing to Le Havre when Dieppe was closed to civilians. Not out of fear of U-boats, he said. He thought a U-boat had more to fear from being rammed by a steamer than the steamer had of being torpedoed. And this at time when U-boats were bringing the country to within seven days of defeat. However he did send his sister some verse ( Last Poems IV) when her son was killed in action. Poetry, he said, is to harmonise the sadness of the universe.

The War changed nothing, he claimed. But of course it did. Nothing was ever the same again. His particular kind of scholarship to begin with. He'd always said a scholar had no more concern with the beauty of a text than a botanist had with a flower's. Now he had. Content suddenly mattered, not just form.

Last Poems came out in 1922, the year that Moses Jackson died of stomach cancer in Vancouver. It's very likely the book was written and put together (several poems date from the '90s) just for him. Jackson read it before he died. The letter Housman wrote has not been made public, but is said to very self-revealing.

Still, he still took afternoon walks in a school-boyish cricket cap, grey suit, starched collar and elastic sided boots. He said 'hello' to no one; this was walking time, talking was for dinner. Every year, too, he vacationed on the Continent; flew there, presumably in converted bombers when passenger flights were in the pioneer stage and the crockery was real, the cutlery silver.

He'd lived in the same three Victorian rooms ('bare, bleak, grim, stark, comfortless,' various people called them) until he was too frail to climb the stairs. For a time he lived in Trinity's older buildings before going to a nursing home in Trumpington Street where he died, in his sleep during the day.

They buried him in Ludlow, for some reason. His brother, Laurence (the painter, poet and playwright) brought out More Poems and Additional Poem s after his death. All four books are still read and on sale in the bigger London bookstores, which won't stock anything that isn't guaranteed to turn a penny (or make a quick buck). In England a Housman Society is dedicated to him. Composers such as Vaughan Williams, George Butterworth, John Ireland, Bax and Bliss, and seemingly dozens of others set his poems to music. The music is still played, the songs still sung.

Some found him impossible; he could be cold, cutting, and sarcastic. Others remember him playing with the Master of Trinity's grandchildren (and their toys). His problem was he couldn't relate to others, through shyness or because of what had happened to him. Small talk didn't come easily (didn't in fact come at all), and as a dinner guest his long silences could be a problem. But he was, for example, at ease with his brother, Basil, and his sister-in-law, Jeannie. They therefore knew a different man — a happy, teasing, slightly bantering older brother — and were puzzled by his forbidding reputation. His brother, Laurence, also said of him: 'he had the happiest laugh I've ever heard.' And he was widely known for his wit and humour (albeit waspish, dry, donnish) both in conversation and in the Prefaces to his editions of Lucan, Juvenal and Manilius. Of Merrill's Catullus : 'half the ship's cargo has been thrown overboard to save the bilge water.' Of Jowett's Plato : 'the best translation of a Greek philosopher which has ever been executed by a person who understood neither philosophy nor Greek.' Of Meredith: ' Meredith has never been treated justly. He once wrote admirable books which were not admired. He now writes ridiculous books which are not ridiculed.' 'Any fool can write a sonnet, and most fools do.' And, in a letter; 'Death and marriage are raging though this College with such fury that I ought to be grateful for having escaped both.' But one of them, of course, he couldn't escape from forever; he died in 1936.

Bibliography

A. E. Housman: A Reassessment ed. Alan W Holden & J Roy Birch London:, MacMillan, 2000.

Graves, Richard. Perceval. A. E. Housman: The Scholar-Poet . London: Routledge, 1979.

Housman, A. E. Introductory Lecture 1892 . Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1937.

Housman, A. E. Selected Prose . Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1961.

Housman, Laurence. A E H . London: Jonathan Cape, 1937.

Larkin, Philip. Required Reading . London: Faber and Faber 1983

Page, Norman. A. E. Housman: A Critical Biography . London: MacMillan, 1996.

Richards, Grant. Housman . Oxford: Oxford UP, 1941.

Stoppard, Tom. The Invention of Love Sir . London: Faber & Faber, 1997.

Last modified 8 June 2007

IMAGES

VIDEO