Short Essay on Save Animals [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

In this session, you will know how you can write essays on Save Animals . Here I will write three sets of essays on the same topic covering different word limits concerning the different exam patterns.

Table of Contents

Short essay on save animals in 100 words, short essay on save animals in 200 words, short essay on save animals in 400 words.

As part of the ecosystem, all living beings have the right to survive. A force in the world can claim the life of a living creature, be it an animal, bird, or human being. Even mute animals have reasons and purposes to survive. So if they are uselessly harmed then humans have to protest against that. The wildlife must be saved through protection laws and creating specific spaces for them.

Several campaigns like ‘’ save animals’’ are produced often to rescue wildlife from unnecessary hunting, skinning, and selling of animals. Excessive violence towards the animals will lead to the disbalance of the ecosystem. Thus wildlife sanctuaries, bird museums, reserve forests, and zoos are created for the preservation of animals.

As human beings, it is our responsibility to create a safe and secure place for all living beings on earth. We must remember that we share the earth with different parts of the ecosystem. The ecosystem includes flora and fauna; the fauna again has several animals and birds to survive on earth.

While humans are rational creatures, they also must keep their aggression against animals in check. They must remember one thing for sure- that they share the earth with everyone. Animals and birds are not provided with a more thoughtful system so that they can protect themselves. So often they are victims of hunting and poaching. They are sold at high rates and killed for human benefit.

Killing and selling animals have a huge demand in the local as well as the international markets. The tusks, skins, nails, teeth, and other parts of the animal body are used to manufacture different products for decoration. But while humans enjoy these products, we forget how we are affecting the ecosystem of the earth.

Even the loss of one animal can lead to severe imbalances in the food chain of the world. Thus saving animals is one of the primary duties of all human beings. If we pledge to care for them, then they can find a more secure place on earth. Saving the animals is our biggest virtue.

Nowadays several issues and problems on earth get covered by the media and campaigns. One of the most significant campaigns that often attracts our attention is the ‘’save animals’’ campaign, which is organized in several parts of the world. Now, why is it important to save the animals or what outcome will that bring if we save animals? Let us discuss this in greater detail.

When the earth was first created several life forms started occupying it. The world was soon populated by ye smallest as well as the largest creatures. While the microscopic organisms survived beyond our notice, huge animals like the dinosaurs and even the most intelligent animals such as humans both survived on earth at different periods of time.

So humans are equipped with the power to rescue all animals on the earth. It is one of the most important duties of humans to look after their fellow beings that they are surrounded. The campaigns conducted for the safety of animals are important which helps to spread awareness regarding them.

Animal safety is important as they build up our ecosystem and a little imbalance in their quantity can create a great problem in the life cycle of the earth. Often laws are made to deforest several acres of land and also to hunt a specific group of animals for human benefit. Recently a law has been published in Canada to hunt and kill several wolves for making some industries.

Almost immediately several campaigns were organized to protect the rights of the wild animals. Pledges were signed, petitions were written, and campaign walks were organized to save wildlife. So it becomes quite important for humans to consider the safety of the animals as well as themselves.

Animals are mostly terrified of hunting and poaching. Baby animals are targeted the most. They are hunted and often trapped for selling them to circus companies. Even these cubs are killed for their meat and skin, which have huge demands in the market. The skins, teeth, nails, hooves, tusks, and meat are sold for creating sophisticated things. Also, deforestation is a principal reason for the depletion of animals.

Hence what is the greatest duty is to reduce human aggression towards animals as they are all parts of the same nature we use. Like our blood relatives, these animals are related to us. So protecting them is our primary job. If animals are saved then we can create great harmony between ourselves and the world.

Hopefully, after going through this session, all your doubts have been resolved. If you still have any, kindly let me know through some quick comments. I will try to attend to your query as soon as possible. Keep browsing our website for more such sessions on various other types of English comprehension.

Join us on Telegram to get all the latest updates on our upcoming sessions. Thank you for being with us. Have a nice day.

More from English Compositions

- 100, 200, 400 Words Paragraph and Short Essay [With PDF]

- Short Essay on Kindness to Animals [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- Short Essay on Save Tigers [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- Short Essay on My Favourite Bird [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- Short Essay on Eagle Bird [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- Madhyamik English Writing Suggestion 2022 [With PDF]

- Short Essay on the Beauty of Nature [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- Short Essay on Elephant [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- Write a Letter to Your Friend Wishing Him Good Luck with His Exam

- Short Essay on Monkey [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- Short Essay on Pigeon [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- Short Essay on Value of Life [100, 200, 400 Words] With PDF

- OneKind Planet Home

OneKindPlanet

Animal facts, education & inspiration

Why save endangered animals?

01/12/1974 by Jane Warley

From Amur Leopards , Black Rhinos and Bornean Orangutans to Hawksbill Turtles , Vaquitas and bluefin tuna, there are many endangered animals that are at risk of extinction. What that means is that we are at risk of losing these animals completely.

We put considerable time, effort and money into saving endangered animals, but why? Extinction is a natural process that would happen with or without humans. But, while that is the case, research shows that extinctions are happening quicker now than ever before. And, loss of habitat is by far the biggest cause. This is a problem that we need to address, and here are a few reasons why.

1. For the enjoyment of future generations

One of the strongest arguments for saving endangered animals is simply that we want to. We get a lot of pleasure out of seeing and interacting with animals. Species that go extinct now are no longer around for us or future generations to see and enjoy. They can only learn about them in books and on the internet. And, that is heartbreaking.

2. For the environment and other animals

Everything in nature is connected. If you remove one animal or plant it upsets the balance of nature, can change the ecosystem completely and may cause other animals to suffer. For example, bees may seem small and insignificant, but they have a huge role to play in our ecosystem – they are pollinators. This means they are responsible for the reproduction plants. Without bees, many plant species would go extinct, which would upset the entire foodchain. Read more about bees here .

3. For medicinal purposes

Many of our medicines have come from or been inspired by nature. The loss of plants and animals to extinction takes with it the potential for new cures and drugs that we have yet to discover.

What can you do to help endangered animals?

There are many things we can do to help endangered animals, here are a few suggestions.

- Protect wildlife habitats. Habitat loss is one of the biggest causes of extinction. Do your bit to preserve wildlife habitats. Volunteer to maintain a local nature reserve, campaign against deforestation or create a space for nature in your garden.

- Educate others. People are more likely to want to save animals if they know about them. Spend time doing some research and spread the word.

- Stay away from pesticides and herbicides. Animals are venerable to pollutants that can build up in the environment and can die if they consume high levels.

- Shop ethically. Avoid buying products made from endangered animals, such as rhino horns .

- Be an ethical tourist. We all love spending time with animals, but the rise of animal experiences abroad is endangering the lives of many animals. Often they are treated cruelly and kept t in unsatisfactory conditions. Pick your experiences wisely, find out more here .

Filed Under: Blog

By continuing to use the site, you agree to the use of cookies. More information Accept

The cookie settings on this website are set to "allow cookies" to give you the best browsing experience possible. If you continue to use this website without changing your cookie settings or you click "Accept" below then you are consenting to this. For further information visit www.aboutcookies.org or www.allaboutcookies.org. You can set your browser not to accept cookies and the above websites tell you how to remove cookies from your browser. Some of our website features may not function as a result.

November 1, 2023

20 min read

Can We Save Every Species from Extinction?

The Endangered Species Act requires that every U.S. plant and animal be saved from extinction, but after 50 years, we have to do much more to prevent a biodiversity crisis

By Robert Kunzig

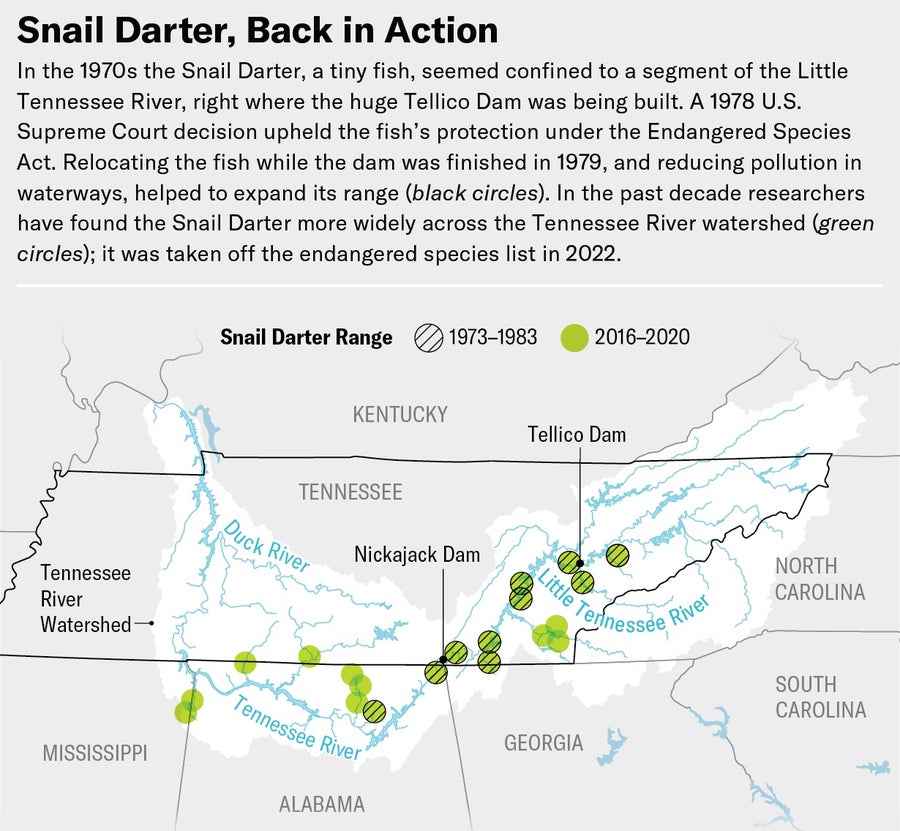

Snail Darter Percina tanasi. Listed as Endangered: 1975. Status: Delisted in 2022.

© Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

A Bald Eagle disappeared into the trees on the far bank of the Tennessee River just as the two researchers at the bow of our modest motorboat began hauling in the trawl net. Eagles have rebounded so well that it's unusual not to see one here these days, Warren Stiles of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told me as the net got closer. On an almost cloudless spring morning in the 50th year of the Endangered Species Act, only a third of a mile downstream from the Tennessee Valley Authority's big Nickajack Dam, we were searching for one of the ESA's more notorious beneficiaries: the Snail Darter. A few months earlier Stiles and the FWS had decided that, like the Bald Eagle, the little fish no longer belonged on the ESA's endangered species list. We were hoping to catch the first nonendangered specimen.

Dave Matthews, a TVA biologist, helped Stiles empty the trawl. Bits of wood and rock spilled onto the deck, along with a Common Logperch maybe six inches long. So did an even smaller fish; a hair over two inches, it had alternating vertical bands of dark and light brown, each flecked with the other color, a pattern that would have made it hard to see against the gravelly river bottom. It was a Snail Darter in its second year, Matthews said, not yet full-grown.

Everybody loves a Bald Eagle. There is much less consensus about the Snail Darter. Yet it epitomizes the main controversy still swirling around the ESA, signed into law on December 28, 1973, by President Richard Nixon: Can we save all the obscure species of this world, and should we even try, if they get in the way of human imperatives? The TVA didn't think so in the 1970s, when the plight of the Snail Darter—an early entry on the endangered species list—temporarily stopped the agency from completing a huge dam. When the U.S. attorney general argued the TVA's case before the Supreme Court with the aim of sidestepping the law, he waved a jar that held a dead, preserved Snail Darter in front of the nine judges in black robes, seeking to convey its insignificance.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Now I was looking at a living specimen. It darted around the bottom of a white bucket, bonking its nose against the side and delicately fluttering the translucent fins that swept back toward its tail.

“It's kind of cute,” I said.

Matthews laughed and slapped me on the shoulder. “I like this guy!” he said. “Most people are like, ‘Really? That's it?’ ” He took a picture of the fish and clipped a sliver off its tail fin for DNA analysis but left it otherwise unharmed. Then he had me pour it back into the river. The next trawl, a few miles downstream, brought up seven more specimens.

In the late 1970s the Snail Darter seemed confined to a single stretch of a single tributary of the Tennessee River, the Little Tennessee, and to be doomed by the TVA's ill-considered Tellico Dam, which was being built on the tributary. The first step on its twisting path to recovery came in 1978, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, surprisingly, that the ESA gave the darter priority even over an almost finished dam. “It was when the government stood up and said, ‘Every species matters, and we meant it when we said we're going to protect every species under the Endangered Species Act,’” says Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus. Listed as Endangered: 1967. Status: Delisted in 2007. Credit: © Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

Today the Snail Darter can be found along 400 miles of the river's main stem and multiple tributaries. ESA enforcement has saved dozens of other species from extinction. Bald Eagles, American Alligators and Peregrine Falcons are just a few of the roughly 60 species that had recovered enough to be “delisted” by late 2023.

And yet the U.S., like the planet as a whole, faces a growing biodiversity crisis. Less than 6 percent of the animals and plants ever placed on the list have been delisted; many of the rest have made scant progress toward recovery. What's more, the list is far from complete: roughly a third of all vertebrates and vascular plants in the U.S. are vulnerable to extinction, says Bruce Stein, chief scientist at the National Wildlife Federation. Populations are falling even for species that aren't yet in danger. “There are a third fewer birds flying around now than in the 1970s,” Stein says. We're much less likely to see a White-throated Sparrow or a Red-winged Blackbird, for example, even though neither species is yet endangered.

The U.S. is far emptier of wildlife sights and sounds than it was 50 years ago, primarily because habitat—forests, grasslands, rivers—has been relentlessly appropriated for human purposes. The ESA was never designed to stop that trend, any more than it is equipped to deal with the next massive threat to wildlife: climate change. Nevertheless, its many proponents say, it is a powerful, foresightful law that we could implement more wisely and effectively, perhaps especially to foster stewardship among private landowners. And modest new measures, such as the Recovering America's Wildlife Act—a bill with bipartisan support—could further protect flora and fauna.

That is, if special interests don't flout the law. After the 1978 Supreme Court decision, Congress passed a special exemption to the ESA allowing the TVA to complete the Tellico Dam. The Snail Darter managed to survive because the TVA transplanted some of the fish from the Little Tennessee, because remnant populations turned up elsewhere in the Tennessee Valley, and because local rivers and streams slowly became less polluted following the 1972 Clean Water Act, which helped fish rebound.

Under pressure from people enforcing the ESA, the TVA also changed the way it managed its dams throughout the valley. It started aerating the depths of its reservoirs, in some places by injecting oxygen. It began releasing water from the dams more regularly to maintain a minimum flow that sweeps silt off the river bottom, exposing the clean gravel that Snail Darters need to lay their eggs and feed on snails. The river system “is acting more like a real river,” Matthews says. Basically, the TVA started considering the needs of wildlife, which is really what the ESA requires. “The Endangered Species Act works,” Matthews says. “With just a little bit of help, [wildlife] can recover.”

The trouble is that many animals and plants aren't getting that help—because government resources are too limited, because private landowners are alienated by the ESA instead of engaged with it, and because as a nation the U.S. has never fully committed to the ESA's essence. Instead, for half a century, the law has been one more thing that polarizes people's thinking.

I t may seem impossible today to imagine the political consensus that prevailed on environmental matters in 1973. The U.S. Senate approved the ESA unanimously, and the House passed it by a vote of 390 to 12. “Some people have referred to it as almost a statement of religion coming out of the Congress,” says Gary Frazer, who as assistant director for ecological services at the FWS has been overseeing the act's implementation for nearly 25 years.

Gopher Tortoise Gopherus polyphemus . Listed as Threatened: 1987. Status: Still threatened. Credit: ©Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

But loss of faith began five years later with the Snail Darter case. Congresspeople who had been thinking of eagles, bears and Whooping Cranes when they passed the ESA, and had not fully appreciated the reach of the sweeping language they had approved, were disabused by the Supreme Court. It found that the legislation had created, “wisely or not ... an absolute duty to preserve all endangered species,” Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said after the Snail Darter case concluded. Even a recently discovered tiny fish had to be saved, “whatever the cost,” he wrote in the decision.

Was that wise? For both environmentalists such as Curry and many nonenvironmentalists, the answer has always been absolutely. The ESA “is the basic Bill of Rights for species other than ourselves,” says National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore, who is building a “photo ark” of every animal visible to the naked eye as a record against extinction. (He has taken studio portraits of 15,000 species so far.) But to critics, the Snail Darter decision always defied common sense. They thought it was “crazy,” says Michael Bean, a leading ESA expert, now retired from the Environmental Defense Fund. “That dichotomy of view has remained with us for the past 45 years.”

According to veteran Washington, D.C., environmental attorney Lowell E. Baier, author of a new history called The Codex of the Endangered Species Act, both the act itself and its early implementation reflected a top-down, federal “command-and-control mentality” that still breeds resentment. FWS field agents in the early days often saw themselves as combat biologists enforcing the act's prohibitions. After the Northern Spotted Owl's listing got tangled up in a bitter 1990s conflict over logging of old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest, the FWS became more flexible in working out arrangements. “But the dark mythology of the first 20 years continues in the minds of much of America,” Baier says.

Credit: June Minju Kim ( map ); Source: David Matthews, Tennessee Valley Authority ( reference )

The law can impose real burdens on landowners. Before doing anything that might “harass” or “harm” an endangered species, including modifying its habitat, they need to get a permit from the FWS and present a “habitat conservation plan.” Prosecutions aren't common, because evidence can be elusive, but what Bean calls “the cloud of uncertainty” surrounding what landowners can and cannot do can be distressing.

Requirements the ESA places on federal agencies such as the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management—or on the TVA—can have large economic impacts. Section 7 of the act prohibits agencies from taking, permitting or funding any action that is likely to “jeopardize the continued existence” of a listed species. If jeopardy seems possible, the agency must consult with the FWS first (or the National Marine Fisheries Service for marine species) and seek alternative plans.

“When people talk about how the ESA stops projects, they've been talking about section 7,” says conservation biologist Jacob Malcom. The Northern Spotted Owl is a strong example: an economic analysis suggests the logging restrictions eliminated thousands of timber-industry jobs, fueling conservative arguments that the ESA harms humans and economic growth.

In recent decades, however, that view has been based “on anecdote, not evidence,” Malcom claims. At Defenders of Wildlife, where he worked until 2022 (he's now at the U.S. Department of the Interior), he and his colleagues analyzed 88,290 consultations between the FWS and other agencies from 2008 to 2015. “Zero projects were stopped,” Malcom says. His group also found that federal agencies were only rarely taking the active measures to recover a species that section 7 requires—like what the TVA did for the Snail Darter. For many listed species, the FWS does not even have recovery plans.

Endangered species also might not recover because “most species are not receiving protection until they have reached dangerously low population sizes,” according to a 2022 study by Erich K. Eberhard of Columbia University and his colleagues. Most listings occur only after the FWS has been petitioned or sued by an environmental group—often the Center for Biological Diversity, which claims credit for 742 listings. Years may go by between petition and listing, during which time the species' population dwindles. Noah Greenwald, the center's endangered species director, thinks the FWS avoids listings to avoid controversy—that it has internalized opposition to the ESA.

He and other experts also say that work regarding endangered species is drastically underfunded. As more species are listed, the funding per species declines. “Congress hasn't come to grips with the biodiversity crisis,” says Baier, who lobbies lawmakers regularly. “When you talk to them about biodiversity, their eyes glaze over.” Just this year federal lawmakers enacted a special provision exempting the Mountain Valley Pipeline from the ESA and other challenges, much as Congress had exempted the Tellico Dam. Environmentalists say the gas pipeline, running from West Virginia to Virginia, threatens the Candy Darter, a colorful small fish. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provided a rare bit of good news: it granted the FWS $62.5 million to hire more biologists to prepare recovery plans.

The ESA is often likened to an emergency room for species: overcrowded and understaffed, it has somehow managed to keep patients alive, but it doesn't do much more. The law contains no mandate to restore ecosystems to health even though it recognizes such work as essential for thriving wildlife. “Its goal is to make things better, but its tools are designed to keep things from getting worse,” Bean says. Its ability to do even that will be severely tested in coming decades by threats it was never designed to confront.

T he ESA requires a species to be listed as “threatened” if it might be in danger of extinction in the “foreseeable future.” The foreseeable future will be warmer. Rising average temperatures are a problem, but higher heat extremes are a bigger threat, according to a 2020 study.

Scientists have named climate change as the main cause of only a few extinctions worldwide. But experts expect that number to surge. Climate change has been “a factor in almost every species we've listed in at least the past 15 years,” Frazer says. Yet scientists struggle to forecast whether individual species can “persist in place or shift in space”—as Stein and his co-authors put it in a recent paper—or will be unable to adapt at all and will go extinct. On June 30 the FWS issued a new rule that will make it easier to move species outside their historical range—a practice it once forbade except in extreme circumstances.

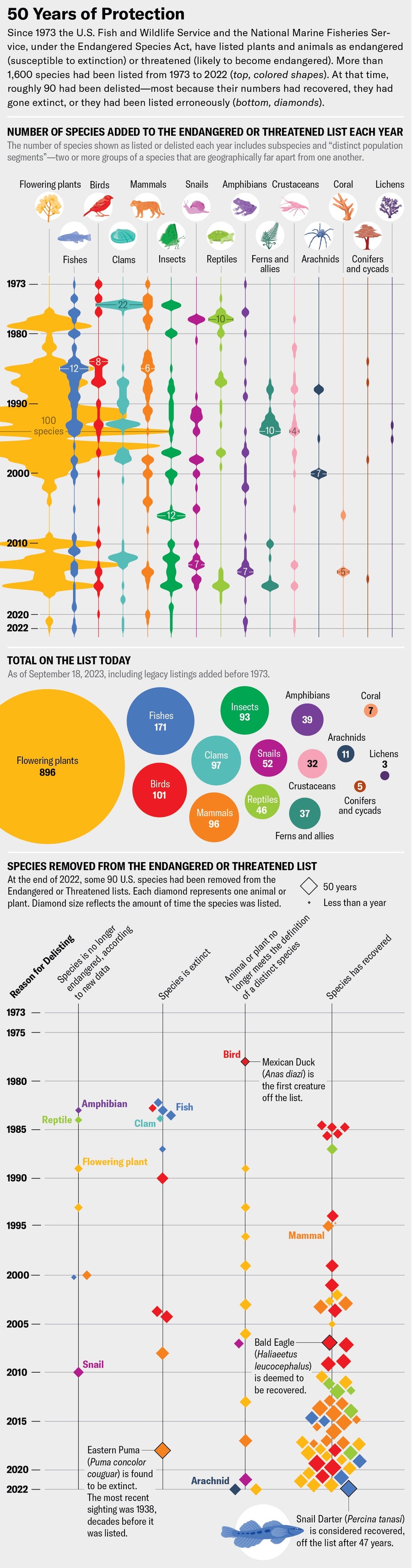

Credit: June Minju Kim ( graphic ); Brown Bird Design ( illustrations ); Sources: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Environmental Conservation Online System; U.S. Federal Endangered and Threatened Species by Calendar Year https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/species-listings-by-year-totals ( annual data through 2022 ); Listed Species Summary (Boxscore) https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/boxscore ( cumulative data up to September 18, 2023, and annual data for coral ); Delisted Species https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/species-delisted ( delisted data through 2022 )

Eventually, though, “climate change is going to swamp the ESA,” says J. B. Ruhl, a law professor at Vanderbilt University, who has been writing about the problem for decades. “As more and more species are threatened, I don't know what the agency does with that.” To offer a practical answer, in a 2008 paper he urged the FWS to aggressively identify the species most at risk and not waste resources on ones that seem sure to expire.

Yet when I asked Frazer which urgent issues were commanding his attention right now, his first thought wasn't climate; it was renewable energy. “Renewable energy is going to leave a big footprint on the planet and on our country,” he says, some of it threatening plants and animals if not implemented well. “The Inflation Reduction Act is going to lead to an explosion of more wind and solar across the landscape.

Long before President Joe Biden signed that landmark law, conflicts were proliferating: Desert Tortoise versus solar farms in the Mojave Desert, Golden Eagles versus wind farms in Wyoming, Tiehm's Buckwheat (a little desert flower) versus lithium mining in Nevada. The mine case is a close parallel to that of Snail Darters versus the Tellico Dam. The flower, listed as endangered just last year, grows on only a few acres of mountainside in western Nevada, right where a mining company wants to extract lithium. The Center for Biological Diversity has led the fight to save it. Elsewhere in Nevada people have used the ESA to stop, for the moment, a proposed geothermal plant that might threaten the two-inch Dixie Valley Toad, discovered in 2017 and also declared endangered last year.

Does an absolute duty to preserve all endangered species make sense in such places? In a recent essay entitled “A Time for Triage,” Columbia law professor Michael Gerrard argues that “the environmental community has trade-off denial. We don't recognize that it's too late to preserve everything we consider precious.” In his view, given the urgency of building the infrastructure to fight climate change, we need to be willing to let a species go after we've done our best to save it. Environmental lawyers adept at challenging fossil-fuel projects, using the ESA and other statutes, should consider holding their fire against renewable installations. “Just because you have bullets doesn't mean you shoot them in every direction,” Gerrard says. “You pick your targets.” In the long run, he and others argue, climate change poses a bigger threat to wildlife than wind turbines and solar farms do.

For now habitat loss remains the overwhelming threat. What's truly needed to preserve the U.S.'s wondrous biodiversity, both Stein and Ruhl say, is a national network of conserved ecosystems. That won't be built with our present politics. But two more practical initiatives might help.

The first is the Recovering America's Wildlife Act, which narrowly missed passage in 2022 and has been reintroduced this year. It builds on the success of the 1937 Pittman-Robertson Act, which funds state wildlife agencies through a federal excise tax on guns and ammunition. That law was adopted to address a decline in game species that had hunters alarmed. The state refuges and other programs it funded are why deer, ducks and Wild Turkeys are no longer scarce.

The recovery act would provide $1.3 billion a year to states and nearly $100 million to Native American tribes to conserve nongame species. It has bipartisan support, in part, Stein says, because it would help arrest the decline of a species before the ESA's “regulatory hammer” falls. Although it would be a large boost to state wildlife budgets, the funding would be a rounding error in federal spending. But last year Congress couldn't agree on how to pay for the measure. Passage “would be a really big deal for nature,” Curry says.

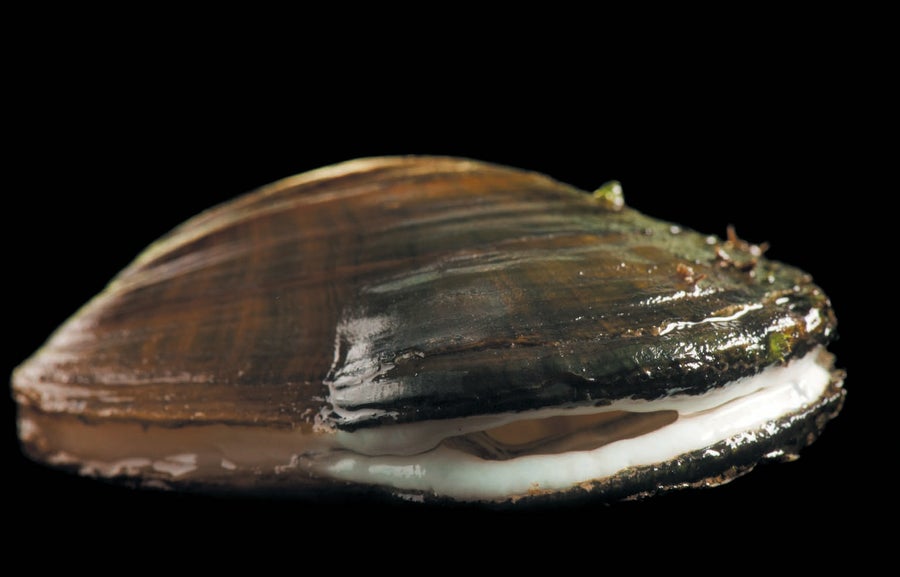

Oyster Mussel. Epioblasma capsaeformis. Listed as Endangered: 1997. Status: Still endangered. Credit: © Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

The second initiative that could promote species conservation is already underway: bringing landowners into the fold. Most wildlife habitat east of the Rocky Mountains is on private land. That's also where habitat loss is happening fastest. Some experts say conservation isn't likely to succeed unless the FWS works more collaboratively with landowners, adding carrots to the ESA's regulatory stick. Bean has long promoted the idea, including when he worked at the Interior Department from 2009 to early 2017. The approach started, he says, with the Red-cockaded Woodpecker.

When the ESA was passed, there were fewer than 10,000 Red-cockaded Woodpeckers left of the millions that had once lived in the Southeast. Humans had cut down the old pine trees, chiefly Longleaf Pine, that the birds excavate cavities in for roosting and nesting. An appropriate tree has to be large, at least 60 to 80 years old, and there aren't many like that left. The longleaf forest, which once carpeted up to 90 million acres from Virginia to Texas, has been reduced to less than three million acres of fragments.

In the 1980s the ESA wasn't helping because it provided little incentive to preserve forest on private land. In fact, Bean says, it did the opposite: landowners would sometimes clear-cut potential woodpecker habitat just to avoid the law's constraints. The woodpecker population continued to drop until the 1990s. That's when Bean and his Environmental Defense Fund colleagues persuaded the FWS to adopt “safe-harbor agreements” as a simple solution. An agreement promised landowners that if they let pines grow older or took other woodpecker-friendly measures, they wouldn't be punished; they remained free to decide later to cut the forest back to the baseline condition it had been in when the agreement was signed.

That modest carrot was inducement enough to quiet the chainsaws in some places. “The downward trends have been reversed,” Bean says. “In places like South Carolina, where they have literally hundreds of thousands of acres of privately owned forest enrolled, Red-cockaded Woodpecker numbers have shot up dramatically.”

The woodpecker is still endangered. It still needs help. Because there aren't enough old pines, land managers are inserting lined, artificial cavities into younger trees and sometimes moving birds into them to expand the population. They are also using prescribed fires or power tools to keep the longleaf understory open and grassy, the way fires set by lightning or Indigenous people once kept it and the way the woodpeckers like it. Most of this work is taking place, and most Red-cockaded Woodpeckers are still living, on state or federal land such as military bases. But a lot more longleaf must be restored to get the birds delisted, which means collaborating with private landowners, who own 80 percent of the habitat.

Leo Miranda-Castro, who retired last December as director of the FWS's southeast region, says the collaborative approach took hold at regional headquarters in Atlanta in 2010. The Center for Biological Diversity had dropped a “mega petition” demanding that the FWS consider 404 new species for listing. The volume would have been “overwhelming,” Miranda-Castro says. “That's when we decided, ‘Hey, we cannot do this in the traditional way.’ The fear of listing so many species was a catalyst” to look for cases where conservation work might make a listing unnecessary.

An agreement affecting the Gopher Tortoise shows what is possible. Like the woodpeckers, it is adapted to open-canopied longleaf forests, where it basks in the sun, feeds on herbaceous plants and digs deep burrows in the sandy soil. The tortoise is a keystone species: more than 300 other animals, including snakes, foxes and skunks, shelter in its burrows. But its numbers have been declining for decades.

Urbanization is the main threat to the tortoises, but timberland can be managed in a way that leaves room for them. Eager to keep the species off the list, timber companies, which own 20 million acres in its range, agreed to figure out how to do that—above all by returning fire to the landscape and keeping the canopy open. One timber company, Resource Management Service, said it would restore Longleaf Pine on about 3,700 acres in the Florida panhandle, perhaps expanding to 200,000 acres eventually. It even offered to bring other endangered species onto its land, which delighted Miranda-Castro: “I had never heard about that happening before.” Last fall the FWS announced that the tortoise didn't need to be listed in most of its range.

Miranda-Castro now directs Conservation Without Conflict, an organization that seeks to foster conversation and negotiation in settings where the ESA has more often generated litigation. “For the first 50 years the stick has been used the most,” Miranda-Castro says. “For the next 50 years we're going to be using the carrots way more.” On his own farm outside Fort Moore, Ga., he grows Longleaf Pine—and Gopher Tortoises are benefiting.

Whooping Crane. Grus americana. Listed as Endangered: 1967. Status: Still endangered. Credit: © Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

The Center for Biological Diversity doubts that carrots alone will save the reptile. It points out that the FWS's own models show small subpopulations vanishing over the next few decades and the total population falling by nearly a third. In August 2023 it filed suit against the FWS, demanding the Gopher Tortoise be listed.

The FWS itself resorted to the stick this year when it listed the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, a bird whose grassland home in the Southern Plains has long been encroached on by agriculture and the energy industry. The Senate promptly voted to overturn that listing, but President Biden promised to veto that measure if it passes the House.

B ehind the debates over strategy lurks the vexing question: Can we save all species? The answer is no. Extinctions will keep happening. In 2021 the FWS proposed to delist 23 more species—not because they had recovered but because they hadn't been seen in decades and were presumed gone. There is a difference, though, between acknowledging the reality of extinction and deliberately deciding to let a species go. Some people are willing to do the latter; others are not. Bean thinks a person's view has a lot to do with how much they've been exposed to wildlife, especially as a child.

Zygmunt Plater, a professor emeritus at Boston College Law School, was the attorney in the 1978 Snail Darter case, fighting for hundreds of farmers whose land would be submerged by the Tellico Dam. At one point in the proceedings Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., asked him, “What purpose is served, if any, by these little darters? Are they used for food?” Plater thinks creatures such as the darter alert us to the threat our actions pose to them and to ourselves. They prompt us to consider alternatives.

The ESA aims to save species, but for that to happen, ecosystems have to be preserved. Protecting the Northern Spotted Owl has saved at least a small fraction of old-growth forest in the Pacific Northwest. Concern about the Red-cockaded Woodpecker and the Gopher Tortoise is aiding the preservation of longleaf forests in the Southeast. The Snail Darter wasn't enough to stop the Tellico Dam, which drowned historic Cherokee sites and 300 farms, mostly for real estate development. But after the controversy, the presence of a couple of endangered mussels did help dissuade the TVA from completing yet another dam, on the Duck River in central Tennessee. That river is now recognized as one of the most biodiverse in North America.

The ESA forced states to take stock of the wildlife they harbored, says Jim Williams, who as a young biologist with the FWS was responsible for listing both the Snail Darter and mussels in the Duck River. Williams grew up in Alabama, where I live. “We didn't know what the hell we had,” he says. “People started looking around and found all sorts of new species.” Many were mussels and little fish. In a 2002 survey, Stein found that Alabama ranked fifth among U.S. states in species diversity. It also ranks second-highest for extinctions; of the 23 extinct species the FWS recently proposed for delisting, eight were mussels, and seven of those were found in Alabama.

One morning this past spring, at a cabin on the banks of Shoal Creek in northern Alabama, I attended a kind of jamboree of local freshwater biologists. At the center of the action, in the shade of a second-floor deck, sat Sartore. He had come to board more species onto his photo ark, and the biologists—most of them from the TVA—were only too glad to help, fanning out to collect critters to be decanted into Sartore's narrow, flood-lit aquarium. He sat hunched before it, a black cloth draped over his head and camera, snapping away like a fashion photographer, occasionally directing whoever was available to prod whatever animal was in the tank into a more artful pose.

As I watched, he photographed a striated darter that didn't yet have a name, a Yellow Bass, an Orangefin Shiner and a giant crayfish discovered in 2011 in the very creek we were at. Sartore's goal is to help people who never meet such creatures feel the weight of extinction—and to have a worthy remembrance of the animals if they do vanish from Earth.

With TVA biologist Todd Amacker, I walked down to the creek and sat on the bank. Amacker is a mussel specialist, following in Williams's footsteps. As his colleagues waded in the shoals with nets, he gave me a quick primer on mussel reproduction. Their peculiar antics made me care even more about their survival.

There are hundreds of freshwater mussel species, Amacker explained, and almost every one tricks a particular species of fish into raising its larvae. The Wavy-rayed Lampmussel, for example, extrudes part of its flesh in the shape of a minnow to lure black bass—and then squirts larvae into the bass's open mouth so they can latch on to its gills and fatten on its blood. Another mussel dangles its larvae at the end of a yard-long fishing line of mucus. The Duck River Darter Snapper—a member of a genus that has already lost most of its species to extinction—lures and then clamps its shell shut on the head of a hapless fish, inoculating it with larvae. “You can't make this up,” Amacker said. Each relationship has evolved over the ages in a particular place.

The small band of biologists who are trying to cultivate the endangered mussels in labs must figure out which fish a particular mussel needs. It's the type of tedious trial-and-error work conservation biologists call “heroic,” the kind that helped to save California Condors and Whooping Cranes. Except these mussels are eyeless, brainless, little brown creatures that few people have ever heard of.

For most mussels, conditions are better now than half a century ago, Amacker said. But some are so rare it's hard to imagine they can be saved. I asked Amacker whether it was worth the effort or whether we just need to accept that we must let some species go. The catch in his voice almost made me regret the question.

“I'm not going to tell you it's not worth the effort,” he said. “It's more that there's no hope for them.” He paused, then collected himself. “Who are we to be the ones responsible for letting a species die?” he went on. “They've been around so long. That's not my answer as a biologist; that's my answer as a human. Who are we to make it happen?”

Robert Kunzig is a freelance writer in Birmingham, Ala., and a former senior editor at National Geographic, Discover and Scientific American .

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Wildlife conservation.

Wildlife conservation aims to protect plant and animal species as the human population encroaches on their resources.

Biology, Ecology, Conservation, Storytelling, Photography

Asian Elephant Family

Filmmakers and photographers are essential to conservation efforts. They take the photographs, such as these Asian elephants (Elephas maximus indicus), and the films that interest others in protecting wildlife.

Photograph by Nuttaya Maneekhot

Wildlife conservation is the practice of protecting plant and animal species and their habitats . Wildlife is integral to the world’s ecosystems , providing balance and stability to nature’s processes. The goal of wildlife conservation is to ensure the survival of these species, and to educate people on living sustainably with other species. The human population has grown exponentially over the past 200 years, to more than eight billion humans as of November 2022, and it continues to rapidly grow. This means natural resources are being consumed faster than ever by the billions of people on the planet. This growth and development also endangers the habitats and existence of various types of wildlife around the world, particularly animals and plants that may be displaced for land development, or used for food or other human purposes. Other threats to wildlife include the introduction of invasive species from other parts of the world, climate change, pollution, hunting, fishing, and poaching. National and international organizations like the World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, the Wildlife Conservation Society, the United Nations, and National Geographic, itself, work to support global animal and habitat conservation efforts on many different fronts. They work with the government to establish and protect public lands, like national parks and wildlife refuges . They help write legislation, such as the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 in the United States, to protect various species. They work with law enforcement to prosecute wildlife crimes, like wildlife trafficking and illegal hunting (poaching). They also promote biodiversity to support the growing human population while preserving existing species and habitats. National Geographic Explorers, like conservation biologists Camille Coudrat and Titus Adhola, are working to slow the extinction of global species and to protect global biodiversity and habitats. Environmental filmmakers and photographers, like Thomas P. Peschak and Joel Sartore, are essential to conservation efforts as well, documenting and bringing attention to endangered wildlife all over the world.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

April 8, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

/

Conservation

In defense of biodiversity: why protecting species from extinction matters.

By Carl Safina • February 12, 2018

A number of biologists have recently made the argument that extinction is part of evolution and that saving species need not be a conservation priority. But this revisionist thinking shows a lack of understanding of evolution and an ignorance of the natural world.

A few years ago, I helped lead a ship-based expedition along south Alaska during which several scientists and noted artists documented and made art from the voluminous plastic trash that washes ashore even there. At Katmai National Park, we packed off several tons of trash from as distant as South Asia. But what made Katmai most memorable was: huge brown bears. Mothers and cubs were out on the flats digging clams. Others were snoozing on dunes. Others were patrolling.

During a rest, several of us were sitting on an enormous drift-log, watching one mother who’d been clamming with three cubs. As the tide flooded the flat, we watched in disbelief as she brought her cubs up to where we were sitting — and stepped up on the log we were on. There was no aggression, no tension; she was relaxed. We gave her some room as she paused on the log, and then she took her cubs past us into a sedge meadow. Because she was so calm, I felt no fear. I felt the gift.

In this protected refuge, bears could afford a generous view of humans. Whoever protected this land certainly had my gratitude.

In the early 20th century, a botanist named Robert F. Griggs discovered Katmai’s volcanic “Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.” In love with the area, he spearheaded efforts to preserve the region’s wonders and wildlife. In 1918, President Woodrow Wilson established Katmai National Monument (now Katmai National Park and Preserve ), protecting 1,700 square miles, thus ensuring a home for bear cubs born a century later, and making possible my indelible experience that day. As a legacy for Griggs’ proclivity to share his love of living things, George Washington University later established the Robert F. Griggs Chair in Biology.

That chair is now occupied by a young professor whose recent writing probably has Griggs spinning in his grave. He is R. Alexander Pyron . A few months ago, The Washington Post published a “ Perspective” piece by Pyron that is an extreme example of a growing minority opinion in the conservation community, one that might be summarized as, “Humans are profoundly altering the planet, so let’s just make peace with the degradation of the natural world.”

No biologist is entitled to butcher the scientific fundamentals on which they hang their opinions.

Pyron’s essay – with lines such as, “The only reason we should conserve biodiversity is for ourselves, to create a stable future for human beings” and “[T]he impulse to conserve for conservation’s sake has taken on an unthinking, unsupported, unnecessary urgency” – left the impression that it was written in a conservative think tank, perhaps by one of the anti-regulatory zealots now filling posts throughout the Trump administration. Pyron’s sentiments weren’t merely oddly out of keeping with the legacy of the man whose name graces his job title. Much of what Pyron wrote is scientifically inaccurate. And where he stepped out of his field into ethics, what he wrote was conceptually confused.

Pyron has since posted, on his website and Facebook page, 1,100 words of frantic backpedaling that land somewhere between apology and retraction, including mea culpas that he “sensationalized” parts of his own argument and “cavalierly glossed over several complex issues.” But Pyron’s original essay and his muddled apology do not change the fact that the beliefs he expressed reflect a disturbing trend that has taken hold among segments of the conservation community. And his article comes at a time when conservation is being assailed from other quarters, with a half-century of federal protections of land being rolled back, the Endangered Species Act now more endangered than ever, and the relationship between extinction and evolution being subjected to confused, book-length mistreatment.

Pyron’s original opinion piece, so clear and unequivocal in its assertions, is a good place to unpack and disentangle accelerating misconceptions about the “desirability” of extinction that are starting to pop up like hallucinogenic mushrooms.

In recent years, some biologists and writers have been distancing themselves from conservation’s bedrock idea that in an increasingly human-dominated world we must find ways to protect and perpetuate natural beauty, wild places, and the living endowment of the planet. In their stead, we are offered visions of human-dominated landscapes in which the stresses of destruction and fragmentation spur evolution.

White rhinoceros ( Ceratotherium simum ). Source: Herman Pijpers/ Flickr

Conservation International ditched its exuberant tropical forest graphic for a new corporate logo whose circle and line were designed to suggest a human head and outstretched arms. A few years ago, Peter Kareiva, then chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy, said , “conservationists will have to jettison their idealized notions of nature, parks, and wilderness,” for “a more optimistic, human-friendly vision.” Human annihilation of the passenger pigeon, he wrote, caused “no catastrophic or even measurable effects,” characterizing the total extinction of the hemisphere’s most abundant bird — whose population went from billions to zero inside a century (certainly a “measurable effect” in itself) — as an example of nature’s “resilience.”

British ecologist Chris Thomas’s recent book, Inheritors of the Earth: How Nature is Thriving in an Age of Extinction, argues that the destruction of nature creates opportunities for evolution of new lifeforms that counterbalance any losses we create, an idea that is certainly optimistic considering the burgeoning lists of endangered species. Are we really ready to consider that disappearing rhinos are somehow counterbalanced by a new subspecies of daisy in a railroad track? Maybe it would be simpler if Thomas and his comrades just said, “We don’t care about nature.’’

Enter Pyron, who — at least in his initial essay — basically said he doesn’t. He’s entitled to his apathy, but no biologist is entitled to butcher the scientific fundamentals on which they hang their opinions.

Pyron began with a resonant story about his nocturnal rediscovery of a South American frog that had been thought recently extinct. He and colleagues collected several that, he reassured us, “are now breeding safely in captivity.” As we breathed a sigh of relief, Pyron added, “But they will go extinct one day, and the world will be none the poorer for it.”

The conviction that today’s slides toward mass extinction are not inevitable spurred the founding of the conservation movement.

I happen to be writing this in the Peruvian Amazon, having just returned from a night walk to a light-trap where I helped a biologist collect moths. No one yet knows how many species live here. Moths are important pollinators. Knowing them helps detangle a little bit of how this rainforest works. So it’s a good night to mention that the number of species in an area carries the technical term “species richness.” More is richer, and fewer is, indeed, poorer. Pyron’s view lies outside scientific consensus and societal values.

Pyron wasn’t concerned about his frogs going extinct, because, “Eventually, they will be replaced by a dozen or a hundred new species that evolve later.” But the timescale would be millennia at best — meaningless in human terms — and perhaps never; hundreds of amphibians worldwide are suffering declines and extinctions, raising the possibility that major lineages and whole groups of species will vanish. Pyron seemed to have no concerns about that possibility, writing, “Mass extinctions periodically wipe out up to 95 percent of all species in one fell swoop; these come every 50 million to 100 million years.”

But that’s misleading. “Periodically” implies regularity. There’s no regularity to mass extinctions. Not in their timing, nor in their causes. The mass extinctions are not related. Three causes of mass extinctions — prolonged worldwide atmosphere-altering volcanic eruptions; a dinosaur-snuffing asteroid hit; and the spreading agriculture, settlement, and sheer human appetite driving extinctions today — are unrelated.

Rio Pescado stubfoot toad ( Atelopus balios ). Source: De Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios/ Flickr

The conviction that today’s slides toward mass extinction are not inevitable, and could be lessened or avoided, spurred the founding of the conservation movement and created the discipline of conservation biology.

But Pyron seems unmoved. “Extinction is the engine of evolution, the mechanism by which natural selection prunes the poorly adapted and allows the hardiest to flourish,” he declared. “Species constantly go extinct, and every species that is alive today will one day follow suit. There is no such thing as an ‘endangered species,’ except for all species.”

Let us unpack. Extinction is not evolution’s driver; survival is. The engine of evolution is survival amidst competition. It’s a little like what drives innovation in business. To see this, let’s simply compare the species diversity of the Northern Hemisphere, where periodic ice sheets largely wiped the slate clean, with those of the tropics, where the evolutionary time clock continued running throughout. A couple of acres in eastern temperate North America might have a dozen tree species or fewer. In the Amazon a similar area can have 300 tree species. All of North American has 1,400 species of trees; Brazil has 8,800. All of North America has just over 900 birds; Colombia has 1,900 species. All of North America has 722 butterfly species. Where I am right now, along the Tambopata River in Peru, biologists have tallied around 1,200 butterfly species.

Competition among living species drives proliferation into diversified specialties. Specialists increasingly exploit narrowing niches. We can think of this as a marketplace of life, where little competition necessitates little specialization, thus little proliferation. An area with many types of trees, for instance, directly causes the evolution of many types of highly specialized pollinating insects, hummingbirds, and pollinating bats, who visit only the “right” trees. Many flowering plants are pollinated by just one specialized species.

Pyron muddles several kinds of extinctions, then serves up further misunderstanding of how evolution works. So let’s clarify. Mass extinctions are global; they involve the whole planet. There have been five mass extinctions and we’ve created a sixth . Past mass extinctions happened when the entire planet became more hostile. Regional wipeouts, as occurred during the ice ages, are not considered mass extinctions, even though many species can go extinct. Even without these major upheavals there are always a few species blinking out due to environmental changes or new competitors. And there are pseudo-extinctions where old forms no longer exist, but only because their descendants have changed through time.

New species do not suddenly “arise,” nor are they really new. They evolve from existing species, as population gene pools change.

Crucially for understanding the relationship between extinction and evolution is this: New species do not suddenly “arise,” nor are they really new. New species evolve from existing species, as population gene pools change. Many “extinct” species never really died out; they just changed into what lives now. Not all the dinosaurs went extinct; theropod dinosaurs survived. They no longer exist because they evolved into what we call birds. Australopithecines no longer exist, but they did not all go extinct. Their children morphed into the genus Homo, and the tool- and fire-making Homo erectus may well have survived to become us. If they indeed are our direct ancestor — as some species was — they are gone now, but no more “extinct” than our own childhood. All species come from ancestors, in lineages that have survived.

Pyron’s contention that the “hardiest” flourish is a common misconception. A sloth needs to be slow; a faster sloth is going to wind up as dinner in a harpy eagle nest. A white bear is not “hardier” than a brown one; the same white fur that provides camouflage in a snowy place will scare away prey in green meadow. Bears with genes for white fur flourished in the Arctic, while brown bears did well amidst tundra and forests. Polar bears evolved from brown bears of the tundra; they got so specialized that they separated, then specialized further. Becoming a species is a process, not an event. “New” species are simply specialized descendants of old species.

True extinctions beget nothing. Humans have recently sped the extinction rate by about a thousand times compared to the fossil record. The fact that the extinction of dinosaurs was followed, over tens of millions of years, by a proliferation of mammals, is irrelevant to present-day decisions about rhinos, elephant populations, or monarch butterflies. Pyron’s statement, “There is no such thing as an ‘endangered species,’ except for all species,” is like saying there are no endangered children except for all children. It’s like answering “Black lives matter” with “All lives matter.” It’s a way of intentionally missing the point.

Chestnut-sided warbler ( Setophaga pensylvanica ). Source: Francesco Veronesi/ Wikimedia

Here’s the point: All life today represents non-extinctions; each species, every living individual, is part of a lineage that has not gone extinct in a billion years.

Pyron also expressed the opinion that “the only reason we should conserve biodiversity is for ourselves …” I don’t know of another biologist who shares this opinion. Pyron’s statement makes little practical sense, because reducing the diversity and abundance of the living world will rob human generations of choices, as values change. Save the passenger pigeon? Too late for that. Whales? A few people acted in time to keep most of them. Elephants? Our descendants will either revile or revere us for what we do while we have the planet’s reins in our hands for a few minutes. We are each newly arrived and temporary tourists on this planet, yet we find ourselves custodians of the world for all people yet unborn. A little humility, and forbearance, might comport.

Thus Pyron’s most jarring assertion: “Extinction does not carry moral significance, even when we have caused it.” That statement is a stranger to thousands of years of philosophy on moral agency and reveals an ignorance of human moral thinking. Moral agency issues from an ability to consider consequences. Humans are the species most capable of such consideration. Thus many philosophers consider humans the only creatures capable of acting as moral agents. An asteroid strike, despite its consequences, has no moral significance. Protecting bears by declaring Katmai National Monument, or un-protecting Bears Ears National Monument, are acts of moral agency. Ending genetic lineages millions of years old, either actively or by the willful neglect that Pyron advocates, certainly qualifies as morally significant.

Do we really wish a world with only what we “rely on for food and shelter?” Do animals have no value if we don’t eat them?

How can we even decide which species we “directly depend’’ upon? We don’t directly depend on peacocks or housecats, leopards or leopard frogs, humpback whales or hummingbirds or chestnut-sided warblers or millions of others. Do we really wish a world with only what we “rely on for food and shelter,” as Pyron seemed to advocate? Do animals have no value if we don’t eat them? I happen not to view my dogs as food, for instance. Things we “rely on” make life possible, sure, but the things we don’t need make life worthwhile.

When Pyron wrote, “Conservation is needed for ourselves and only ourselves… If this means fewer dazzling species, fewer unspoiled forests, less untamed wilderness, so be it,” he expressed a dereliction of the love, fascination, and perspective that motivates the practice of biology.

Here is a real biologist, Alfred Russell Wallace, co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection:

I thought of the long ages of the past during which the successive generations of these things of beauty had run their course … with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness, to all appearances such a wanton waste of beauty… . This consideration must surely tell us that all living things were not made for man… . Their happiness and enjoyments, their loves and hates, their struggles for existence, their vigorous life and early death, would seem to be immediately related to their own well-being and perpetuation alone. —The Malay Archipelago, 1869

At the opposite pole of Wallace’s human insight and wonder, Pyron asked us to become complicit in extinction. “The goals of species conservation have to be aligned with the acceptance that large numbers of animals will go extinct,” he asserted. “Thirty to 40 percent of species may be threatened with extinction in the near future, and their loss may be inevitable. But both the planet and humanity can probably survive or even thrive in a world with fewer species … The species that we rely on for food and shelter are a tiny proportion of total biodiversity, and most humans live in — and rely on — areas of only moderate biodiversity, not the Amazon or the Congo Basin.”

African elephant ( Loxodonta africana ). Source: Flowcomm/ Flickr

Right now, in the Amazon as I type, listening to nocturnal birds and bugs and frogs in this towering emerald cathedral of life, thinking such as Pyron’s strikes me as failing to grasp both the living world and the human spirit.

The massive destruction that Pyron seems to so cavalierly accept isn’t necessary. When I was a kid, there were no ospreys, no bald eagles, no peregrine falcons left around New York City and Long Island where I lived. DDT and other hard pesticides were erasing them from the world. A small handful of passionate people sued to get those pesticides banned, others began breeding captive falcons for later release, and one biologist brought osprey eggs to nests of toxically infertile parents to keep faltering populations on life support. These projects succeeded. All three of these species have recovered spectacularly and now again nest near my Long Island home. Extinction wasn’t a cost of progress; it was an unnecessary cost of carelessness. Humans could work around the needs of these birds, and these creatures could exist around development. But it took some thinking, some hard work, and some tinkering.

It’s not that anyone thinks humans have not greatly changed the world, or will stop changing it. Rather, as the great wildlife ecologist Aldo Leopold wrote in his 1949 classic A Sand County Almanac , “To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

Related Articles

Marina silva on brazil’s fight to turn the tide on deforestation.

By Jill Langlois

Solomon Islands Tribes Sell Carbon Credits, Not Their Trees

By Jo Chandler

With Sea Turtles in Peril, a Call for New Strategies to Save Them

By Richard Schiffman

More From E360

Scientists are trying to coax the ocean to absorb more co2, jared kushner has big plans for delta of europe’s last wild river, a nuclear power revival is sparking a surge in uranium mining, despite official vote, the evidence of the anthropocene is clear, at 11,500 feet, a ‘climate fast’ to save the melting himalaya, octopuses are highly intelligent. should they be farmed for food, nations are undercounting emissions, putting un goals at risk, as carbon air capture ramps up, major hurdles remain, how china became the world’s leader on renewable energy.

Sign up to get the latest WWF news delivered straight to your inbox

Protecting wildlife

The world’s wildlife is being lost up to 10,000 times faster than the natural extinction rate.

Animals and plants aren’t just valuable for their own sake – they’re also part of a wider natural environment that may provide food, shelter, water, and other functions, for other wildlife and people.

With so much wildlife at risk, the question people often ask us is how do we decide which animals and plants to focus our conservation efforts and funds on? Well, it’s not always an easy decision… but we do have criteria to guide us.

For example: 1) is it a species that’s a vital part of a food chain? Or 2) a species that helps demonstrate broader conservation needs? Or 3) is it an important cultural icon that will garner support for wildlife conservation as a whole? These are just some of the considerations.

"Our planet is so special and diverse there are still new species being discovered all the time. Meanwhile we’ve reported the terrifying news that vertebrate species populations have declined on average by over 50% since 1970. Whether your interest in wildlife is for its own intrinsic value or for its contribution to a functioning ecosystem that supports so many species as well as human livelihoods and well-being too, there is no denying that we, people, have an obligation to ensure we not only stop our damaging ways, but look to increase wildlife populations and strengthen the habitats they rely on."

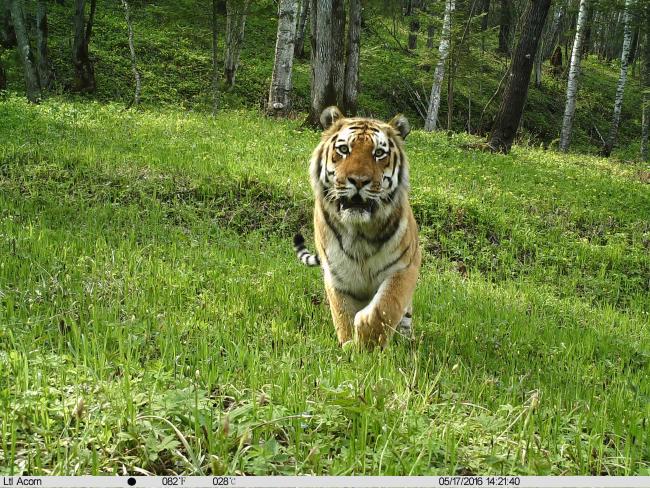

Over the past five decades, our field work has helped bring several iconic animals back from the brink of extinction – including white and greater one-horned rhinos, certain populations of African elephants, mountain gorillas, giant pandas and tigers.

We’ve also achieved important policy changes – for instance: helping bring about the global moratorium on commercial whaling; improving controls for trade in threatened species such as tigers; and regulating trade in over used trees, like mahogany, and fish such as sturgeons (caught for caviar).

Our work hasn’t just given a more certain future for specific wildlife, but has helped thousands more species by contributing to the conservation of all the diversity of life within their environments.

Our wildlife conservation efforts are also directly helping people, through improved livelihoods, food security, access to fresh water, incomes, and by strengthening communities, socially and politically.

The work we do is playing a part in at least five of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals, and contributing to poverty reduction in several parts of the world.

Global wild tiger numbers increase for first time in conservation history

Thanks to the collective efforts by governments and organisations, and the brilliant help of our passionate supporters and colleagues around the world, we were thrilled to see that wild tiger numbers have risen – for the first time in conservation history. Just over a century ago, there were thought to be around 100,000 wild tigers. In the past century, we lost nearly 95% of our wild tigers. By 2010 there were as few as 3,200 left in the wild (to put that in perspective, there are more tigers than this in captivity in the US alone). But due to enthusiastic and determined global efforts, and skilled conservation work on the ground in Asia, wild tiger numbers have now risen to an estimate of around 3,900. We’re stepping up our efforts to help wild tiger populations grow further – and you can help us.

Restoring the Tiger’s Amur Heilong Home Read More

A Corridor for Wildlife and Communities Read More

Plastics: Why we must act now Read More

Wild tiger numbers rise for first time in a century Read More

- Read More Stories

How we're protecting wildlife

Supporting people to support snow leopards

We’re working with communities in the high mountains of China, India and Nepal to help protect snow leopards and other wildlife.

Sound of Safety

We’re working with WWF India and WWF Pakistan to protect river dolphins while improving livelihoods for local fishing communities.

Illegal Wildlife Trade in Nepal

Reducing wildlife trade in Bagmati province, Nepal.

Sustainable fisheries in the Mara wetlands

The UK Government’s Darwin Initiative, funds WWF collaborative work with local partners on sustainable fisheries management in Mara wetlands, Tanzania.

Tackling human-wildlife conflict in Ruvuma

With funding from the UK Government’s Darwin Initiative, WWF is collaborating with local partners to reduce human-wildlife conflict in Ruvuma.

Conserving Otters in the Karnali

Strengthening communities’ livelihood and stewardship to conserve Otters in the Karnali.

Making palm oil sustainable

WWF Malaysia works with plantations to help the endangered Borneo elephant move freely.

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

Essay on Save Animals

Wildlife is a precious gift from God for this planet. The term "fauna" is not only for wild animals but also for all non-domesticated life forms including birds, insects, plants, fungi and even microscopic organisms. To maintain a healthy ecological balance on this land, animals, plants and marine species are as important as humans. Every organism on this earth has a unique place in the food chain that contributes to the ecosystem in its own way. But, unfortunately today, many animals and birds are endangered.

Natural habitats of animals and plants are destroyed for land development and agriculture by humans. Poaching and hunting of animals for fur, jewellery, meat and leather are other important factors contributing to the extinction of wildlife. If soon, no rigorous measures are taken to save the fauna, it would not be long when they find a place on the list of extinct species. And that would not be all! The extinction of wild species will certainly have a fatal impact on the human race. So, for us as human beings, it becomes a great responsibility to save the wildlife, our planet and, most importantly, ourselves. Here are some other reasons for deep understanding why wildlife plays such an important role in maintaining an ecological balance on Earth.

The ecosystem is entirely based on the relationships between different organisms linked by food webs and food chains. Even if a single wild species dies out of the ecosystem, it can disrupt the entire food chain and lead to disastrous results. Consider a simple example of a bee that is vital for the growth of some crops because of their pollen transport roles. If bees are reduced in number, the growth of food crops would decrease significantly due to lack of pollination.

Similarly, if a species becomes larger, it may again have a negative effect on the ecological balance. Consider another simple case of carnivores that is shrinking every day because of human poaching and hunting. The reduction of these carnivores leads to an increase in the number of herbivores that depend on forest vegetation for their survival. It would not be long, when the number of herbivores in the forests would rise to such an extent that they would move to farmland and villages for their food needs. Thus, saving wildlife plays a big role in controlling the ecological balance, maintaining a healthy ecosystem.

The human population depends largely on agricultural crops and plants for their food needs. Do you know that wildlife plays an important role in the growth of these crops? If not, we will understand the concept. The fruits and vegetables that we get from plants are the result of a process called pollination, a reproductive system in plants where the pollen grains of the male flower are transferred to the female flower, resulting in the production of seeds. Now, for pollination to occur, birds, bees and insects, some of the smallest species on this planet, play an important role. It is through these insects and birds that pollens are transferred between the flowers as they pass from one flower to another. Crop growth can be significantly affected if the number of birds and insects carried by the pollen decreases in number for any reason. You would be surprised to know that 90% of the world's apple production depends on the pollination of bees.

In addition to pollination, many birds also play an important role in pest control by feeding on them.

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Animals: Samples in 100, 200 and 300 Words

- Updated on

- Dec 27, 2023

Animals are an important part of the natural world. Their existence in our environment is as important as ours. Some of the common animals that we see regularly are dogs, cats, cows, birds, etc. From small insects to blue whales, there are millions of species of animals in our environment, each having their habitat and way of living. Some animals live in seas, while others on land. Our natural environment is so diverse that there are more than 7 million species of animals currently living. Today, we will provide you with some essay on animals. Stay tuned!

Table of Contents

- 1 Essay on Animals in 100 Words

- 2 Essay on Animals in 200 Words

- 3 Essay on Animals in 300 Words

Also Read: Essay on New Education Policy in 500 Words

Essay on Animals in 100 Words

Animals are part of our natural world. Most of the animal specials are related to humans in direct or indirect ways. In agricultural and dairy production, animals play an important role. Our food, such as eggs, milk, chicken, beef, mutton, fish, etc. all come from animals. Animals are generally of two types; domestic and wild.

Domestic animals are those that we can keep at our homes or use their physical strength for activities like agriculture, farming, etc. Wild animals live in forests, where they have different ways of survival. There is an interdependence between humans and animals. Without animals, our existence would be impossible. Therefore, saving animals is as important as saving ourselves.

Also Read: Essay on Cow: 100 to 500 Words

Essay on Animals in 200 Words

Animals play a major role in maintaining the balance of our ecosystem. They contribute to our biodiversity by enriching the environment with their diverse species. Animals range from microscopic organisms to majestic mammals with their unique place in the intricate web of life.

Animals provide essential ecosystem services, such as pollination, seed dispersal, and pest control, which are vital for the survival of many plant species. Animals contribute to nutrient cycling and help in maintaining the health of ecosystems. Animals have an interdependency on each other which creates a delicate equilibrium. Our activities often disturb his balance, which affects the entire ecosystem.

There are a lot of animals that we can domesticate, such as dogs, cats, cows, horses, etc. These animals bring joy and companionship to our lives. We also domesticate milch animals, such as cows, goats, camels, etc. for services like milk or agricultural activities. Wild animals living in forests contribute to our cultural and aesthetic aspects, inspiring art, literature, and folklore.

In recent years, animal species have faced threats due to habitat destruction, climate change, and human activities. Conservation efforts are crucial to protecting endangered species and preserving the diversity of life on Earth.

Animals are integral to the health of our planet and contribute to the overall well-being of human societies. It is our responsibility to appreciate, respect, and conserve the rich tapestry of animal life for the benefit of present and future generations.

Essay on Animals in 300 Words

Scientific studies say there are 4 types of animals; mammals, fish, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. All these types of animals are important in maintaining the balance of our ecosystem. From the smallest insects to the largest mammals, each species has a unique role to play in the web of life.

One of the fundamental roles of animals is in ecosystem services. Bees and butterflies, for example, are crucial pollinators for many plants, including crops that humans rely on for food. Birds and mammals contribute to seed dispersal, facilitating the growth of various plant species. Predators help control the population of prey animals, preventing overgrazing and maintaining the health of ecosystems.

Beyond their ecological contributions, animals also have immense cultural significance. Throughout history, animals have been revered and represented in art, mythology, and religious beliefs. They symbolize traits such as strength, agility, wisdom, and loyalty, becoming integral to human culture. Domesticated animals, such as dogs and cats, have been companions to humans for thousands of years, providing emotional support and companionship.

However, the impact of human activities on animals is a growing concern. Habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, and poaching pose significant threats to many species. Conservation efforts are crucial to safeguarding biodiversity and ensuring the survival of endangered animals.

Moreover, the well-being of animals is closely linked to human welfare. Livestock and poultry contribute to the global food supply, and advancements in medical research often rely on animal models. Ethical considerations surrounding animal welfare are increasingly important, leading to discussions on responsible and humane treatment.

Animals are essential components of our planet’s ecosystems and contribute significantly to human culture and well-being. Balancing our interactions with animals through conservation, ethical treatment, and sustainable practices is imperative to ensure a harmonious coexistence and preserve the diversity of life on Earth.