Here’s how you know

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- National Institutes of Health

International Health Research

While most of NCCIH’s research support goes to U.S. institutions, we do in some instances support work outside of the United States which is in alignment with our strategic plan and research priorities .

Most work in other countries is supported through subcontracts or consortium agreements of U.S. grantees.

Direct funding of research at foreign institutions is possible under a limited set of grant mechanisms or specifically targeted initiatives. Investigators from non-U.S. institutions interested in direct funding of their research by NCCIH should contact the appropriate NCCIH Program Director to discuss eligibility and opportunities.

Eligibility for Direct Funding Initiatives

NCCIH will not consider applications involving interventional clinical trials outside of the United States and Canada.

Foreign institutions are eligible for funding through direct mechanisms (R01, R21, and R03) only when specified in the PA or RFA. In addition, NCCIH encourages foreign researchers to contact the appropriate NCCIH Program Director noted in the PA or RFA, or on the NCCIH website.

Foreign institutions are not eligible to submit grant applications for the following types of grant mechanisms used by NCCIH:

- Institutional Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards (NRSAs) (T32 mechanism)

- Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Short-Term Research Training (T35 mechanism)

- Program Project Grants (P01 mechanism)

- Center Grants (P30 and P50 mechanisms)

- Resource Grants (P41 mechanisms)

- Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Grants (R41 and R42 mechanisms)

- Conference Grants (R13 mechanism)

- Career Development Awards (all K mechanisms)

- Academic Research Enhancement Awards (R15 mechanism)

- Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Grants (R43 and R44 mechanisms)

Consortium Partnership Type Funding Initiatives

Foreign institutions often receive NIH/NCCIH support as foreign components of a grant made to another research institution. In these cases, the funding flows from the grantee institution to the foreign collaborating institution through a subcontract agreement between the two institutions. The subcontract agreement details the respective roles, activities and responsibilities of both institutions, and any conditions or terms for payment of subcontract funds. These arrangements are developed during the grant application process.

Additional Review Criteria and Funding Considerations

All research proposals submitted to NIH undergo the same process of scientific peer review .

In addition, NIH policy requires that specific criterion be considered in the review process and award decision for foreign grant applicants, including whether the project presents special opportunities for furthering research programs through the use of unusual talent, resources, populations or environmental conditions in other countries that are not readily accessible in the United States, or that augment existing U.S. resources, and whether the proposed project has the potential for significantly advancing the health sciences.

Policy requires that all proposed projects must have specific relevance to the mission and objectives of NCCIH and also stipulates that all foreign grant applications be specifically reviewed and recommended for funding by NCCIH’s National Advisory Council .

Clearance by the U.S. Department of State may also be required, and there may be special requirements of the government of the foreign country in which the research will take place.

NIH Fogarty International Opportunities for Foreign Scientists

The Fogarty International Center is dedicated to advancing the mission of NIH by supporting and facilitating global health research conducted by U.S. and international investigators, building partnerships between health research institutions in the United States and abroad, and training the next generation of scientists to address global health needs. Information on specific opportunities can be found at fic.nih.gov .

For questions about the research project:

Please contact the Program Director who can discuss the scientific area of your research.

For general inquiries about international health research:

Please contact the NCCIH Division of Extramural Research at [email protected] .

- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Health and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Policy and Management

- Health, Behavior and Society

International Health

- Mental Health

- Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

We are committed to improving the health, nutrition, and well-being of the world’s most disadvantaged people with cutting-edge science, responsive and innovative public health practice, educational programs, and focused capacity building.

View Our Program Areas

- IDARE Working and Steering Groups

- Support Groups

- Strategic Plan 2020

- Why we are named the Department of International Health

- Job Openings

- MSPH Practicum Criteria

- MSPH Practicum Preceptor Responsibilities

- Student Publications

- Message from the Director

- Ethics, Equity, and Gender

- Global Health Economics

- Global Health Policy

- Global Health Technology and Innovation

- Uttar Pradesh Health Systems Strengthening Project

- Newsletter Archive

- Primary Health Care and Community Health

- Global Disease Epidemiology and Control

- Academic Guides and Competencies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Program in Applied Vaccine Experiences - PAVE

- Our Work in Action

- Conversations on Sustainable Financing for Development

- Moving from Emergency Response to Post-Recovery: Lessons and Reflections from Ebola

- Polio Eradication: Status, Transition and Legacy

- Supporting Operational AIDS Research (SOAR): Assessing the Geographic Pivot

- The Avahan Experience in India

- Workshop on Strategic Issues in Global Health Program Transitions

- WHERE WE WORK

- Studies by Johns Hopkins Researchers Seek to Improve Mobile Phone Health Surveys in Colombia

Publications

- Our Publications

- Student Investigators

- Leveraging Primary Health Care Systems for COVID-19

- Mission Afghanistan 2030 In the News

- Mission Afghanistan 2030 Publications

- One Year On: The Pervasive Health Challenges in Afghanistan - Webinar Series

- Sight and Life Global Nutrition Research Institute

The IDEA Initiative

- The India Primary Health Care Support Initiative (IPSI)

- Faculty Recognition: Excellence in Teaching

- Mathuram Santosham, MD, MPH, ’75

- Primary Faculty Within the Global Disease Epidemiology and Control Program Area

- Primary Faculty Within the Health Systems Program Area

- Primary Faculty Within the Human Nutrition Program Area

- Primary Faculty Within the Social and Behavioral Interventions Program Area

- International Health Endowed Honors and Student Awards

- Student Profile: Abinethaa Paramasivam

- Student Profile: Deja Knight

- Student Profile: Prativa Baral

- Student Profile: Safia Jiwani

- Student Profile: Venessa Chen

- Alumni Profile: Anita Dam

- Alumni Profile: Lani Rice Marquez

- Alumni Profile: Nimi Georgewill

- Allyson Nelson, MSPH ’15

- Alumna Interview | Rebecca Merrill, PhD ’10, MHS ‘07, Senior Epidemiologist, CDC

- Alumni Profile: Brigitta Szeibert, MSPH ’23, RD

- Andrew Nicholson, MSPH '17

- Andrew Thompson, MSPH '12

- Caitlin Quinn, MSPH '17

- Chytanya Kompala, MSPH

- Collrane Frivold, MSPH ’17

- Elizabeth "Libby" Watts, MHS '17

- Katherine Tomaino, MSPH ’14

- Lianne Marie Gonsalves, MSPH '13

- Marie Spiker, MSPH '14, RD program

- Mariya Patwa, MSPH '18

- Mary Qiu, MSPH '16

- Prianca Reddi, MSPH '20

- Tomoka Nakamura, MSPH '15

- 2024 Vaccine Day at Johns Hopkins

- Bestselling Author Johnny Saldaña Leads Qualitative Data Workshops

- Faculty Profile | Smisha Agarwal, PHD, MPH, MBA

- Faculty Speaks at UN: Launch of Journal Series on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

- From the Chair

- International Health Faculty Key Contributors to First WHO Guideline on Digital Interventions for Health Systems Strengthening

- International Health Faculty Presents Expert Recommendations On Antimicrobial Resistance to UN Secretary General

- International Health Faculty Receives NIH Fogarty Funding to Establish Research Ethics Training Program in Ethiopia

- International Health Faculty Wins Award for Innovation in Nutrition and Health in Developing Societies

- International Health Student and Faculty Publish New Vaccine Safety Book

- Student Spotlight | Maria Garcia Quesada, MSPH '19

- Student Spotlight | Ryan Thompson, MSPH '19

- Alumna Profile | Collrane Frivold, MSPH ‘17

- Alumna Profile | Katherine Tomaino, MSPH ‘14

- Alumni Reunion | The Program in Applied Vaccine Experiences (PAVE)

- Faculty Profile | Haneefa Saleem, PHD ’14, MPH ’09

- Faculty Profile | Naor Bar-Zeev, PHD, MBBS(HONS), MPH, MBIOSTAT

- Student Practicum Spotlight | Greg Rosen, MSPH Candidate

- Student Spotlight | Nukhba Zia, PHD Candidate

- Make a Gift

- Info for Current Students

What's New in the Department of International Health

We're Hiring

The Department of International Health invites applications for the recruitment of up to four tenure-track Assistant, Associate or Full Professor positions. This search is casting a broad net with a view to attracting the best candidates working in global health areas prioritized by the Department’s new Strategic Plan. This is an international search and candidates with relevant qualifications are encouraged to apply regardless of where they reside.

Strategy 2024

We are excited to launch the Department’s 2024 – 2027 Strategic Plan. Priority areas include 1) reinforcing areas of strength and aligning our research and education priorities with the most pressing existing and emerging global health issues 2) tackling persistent operational inefficiencies to positively impact our ability to deliver on our mission, and 3) strengthening our approach to partnership to ensure we focus on long-term, equitable, mutually beneficial partnerships to achieve global impact.

Robert E. Black, MD, MPH

In the second edition of the Department of International Health Legacy Series, Robert E. Black, MD, MPH, discusses his distinguished career in public health. Black was chair of International Health from 1985 to 2013. He was recently honored at the School during the installation of Judd L. Walson as the inaugural Robert E. Black Chair in International Health.

International Health Headlines

Solutions for a livable earth.

From innovating ways to preserve glacial ice to predicting climate-driven migration shifts to building resilient cities, researchers are exploring scalable solutions to safeguard a planet in peril.

As Global Health Programs Transition to Local Entities, Researchers Turn an Eye toward Sustainability

Researchers are examining what factors make programmatic transition successful, equitable, and sustainable.

Cooking Skills: The Missing Ingredient in Nutrition Efforts

If we want to help people eat better, we need to teach them how to cook.

What We Do in the Department of International Health

The Department of International Health is a global leader and partner in identifying, developing, testing, and implementing practices and policies that help the world’s most vulnerable and disadvantaged people improve their health and well-being. We work directly and collaboratively with communities, scientists, public health practitioners, and policymakers around the world to understand their needs and support changes to improve health globally.

International Health Highlights

academic program in international health (1961)

Largest Department in Global Health

over 300 full-time faculty working across the globe

Global Network

have worked in over 90 countries on 6 continents

500+ peer-reviewed articles published a year

International Health Programs

The Department of International Health is organized into four program areas: Global Disease Epidemiology and Control; Health Systems; Human Nutrition; and Social and Behavioral Interventions.

We offer a Master of Science in Public Health (MSPH) and doctoral-level training for research (PhD) in these program areas, as well as a Master of Health Science in Health Economics (MHS). We also offer many continuing education programs online and on campus.

Master of Health Science (MHS) in Global Health Economics

The MHS in Global Health Economics is a nine-month program that provides students with the skills necessary to use economic tools in the promotion of healthy lifestyles and positive health outcomes. Students will learn how to develop health systems that promote equitable access to care, using applied health cases from around the world.

Master of Science in Public Health (MSPH)

The MSPH training program is intended for students who wish to pursue a professional career in the field of public health. Some prior health and/or international experience is preferred.

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)

The PhD prepares students to become independent investigators in academic and non-academic research institutions, and emphasizes contributions to theory and basic science.

Centers, Institutes, and Initiatives in the Department of International Health

The Department is home to a number of centers, institutes, and initiatives that allow faculty from the Department, the University, and the world to collaborate directly on specific global health issues.

Center for Global Digital Health Innovation

Center for human nutrition, center for humanitarian health, center for indigenous health, center for immunization research, center for implementation research & practice, institute for international programs, institute for vaccine safety, international center for maternal & newborn health, international vaccine access center (ivac), johns hopkins international injury research unit (iiru), johns hopkins vaccine initiative, melissa a. marx, phd,.

evaluates maternal, child, and infectious disease programs, and has led response efforts for outbreaks including SARS, Ebola, and COVID-19.

Follow Our Department

Department news, lancet series launch: the current and future outlook for primary health care in south asia.

A new Lancet series draws learnings from implementation of primary health care programs in five South Asian countries.

In the second edition of the Department of International Health Legacy Series, Robert E. Black, MD, MPH, discusses his distinguished career in public health.

Upcoming Events

Support our department.

Support students and promote International Health research, make a donation today.

Global Health

An overview of our research on global health.

By: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser

This page was first published in August 2016, and last revised in February 2024.

Good health is fundamental for a high quality of life, as it influences our ability to enjoy life and participate in daily activities.

On this page, we provide an overview of global health, emphasizing data on health outcomes – such as disease and death – and the effects of healthcare investments.

We begin by examining life expectancy, a primary indicator of population health. Historical trends show us there have been significant increases in global life expectancy over the last two centuries, reflecting improvements around the world.

Notably, poorer countries have made considerable progress, which has helped reduce the global disparity in life expectancy. But substantial gaps remain, with life expectancies in some Sub-Saharan African countries below 60 years, in contrast to over 80 years in several European countries and Japan.

Large reductions in child and maternal mortality have been central to the improvement in life expectancy worldwide. But life expectancy has risen across all age groups.

Despite these advancements, disparities persist — child mortality rates in low-income countries are substantially higher than those in high-income countries. This pattern extends to other health measures, including disease burden estimates, indicating ongoing global health challenges.

A growing body of research highlights the effectiveness of healthcare investments in improving health outcomes. Evidence shows that health outcomes respond positively to increased healthcare spending, particularly at lower levels of expenditure.

This suggests that appropriately targeted and managed international health aid can significantly reduce global health inequalities, and improve living standards worldwide.

See all interactive charts on global health ↓

Life Expectancy

People are living longer across the world, but large differences remain. Explore global data on life expectancy and how it has changed over time.

Child and Infant Mortality

Child mortality remains one of the world’s largest problems and is a painful reminder of work yet to be done. With global data on where, when, and how child deaths occur, we can accelerate efforts to prevent them.

Healthcare Spending

How is healthcare financed? How much do we spend on it? What are the returns?

Health Outcomes

Life expectancy.

To understand the health of a population, one useful approach is to look at life expectancy. This is formally called the “period life expectancy at birth”, and is an indicator that summarizes death rates across all age groups in one particular year.

For a given year, it represents the average lifespan for a hypothetical group of people, if they experienced the same age-specific death rates throughout their whole lives as the age-specific death rates seen in that particular year.

Find much more about the topic of life expectancy on our dedicated page:

How has life expectancy changed in the long run?

The chart below summarises the available data on life expectancy over the last few centuries.

In the United Kingdom, a country for which we have the longest time series of data, the chart shows that life expectancy before 1800 was very low, but since then it has increased drastically.

In less than two centuries, life expectancy in the UK has doubled. The data shows that similarly remarkable improvements also took place in other European countries during this period.

The chart also shows large historical changes in life expectancy estimates for other regions. In the early 1900s, life expectancy in both India and South Korea was less than 25 years. A century later, life expectancy in India had more than doubled, and in South Korea, it had more than tripled.

The map view shows a comparison of life expectancy across countries. As you can see, although the global disparity in life expectancy has reduced substantially, there are still huge differences between countries.

In 2021, the life expectancy in several sub-Saharan African countries is less than 60 years, compared to more than 80 years in countries such as Japan.

Child mortality played a substantial role in increasing overall life expectancy, historically. But in recent decades, as child mortality rates have been at much lower levels, further declines have made much smaller contributions to gains in life expectancy.

Despite this, life expectancy continues to rise in many countries, because death rates have continued to fall across age groups.

You can read more in our article:

It’s not just about child mortality, life expectancy increased at all ages

It’s often argued that life expectancy across the world has only increased because child mortality has fallen. But this is untrue. The data shows that life expectancy has increased at all ages.

Have all countries in the world experienced increasing life expectancy?

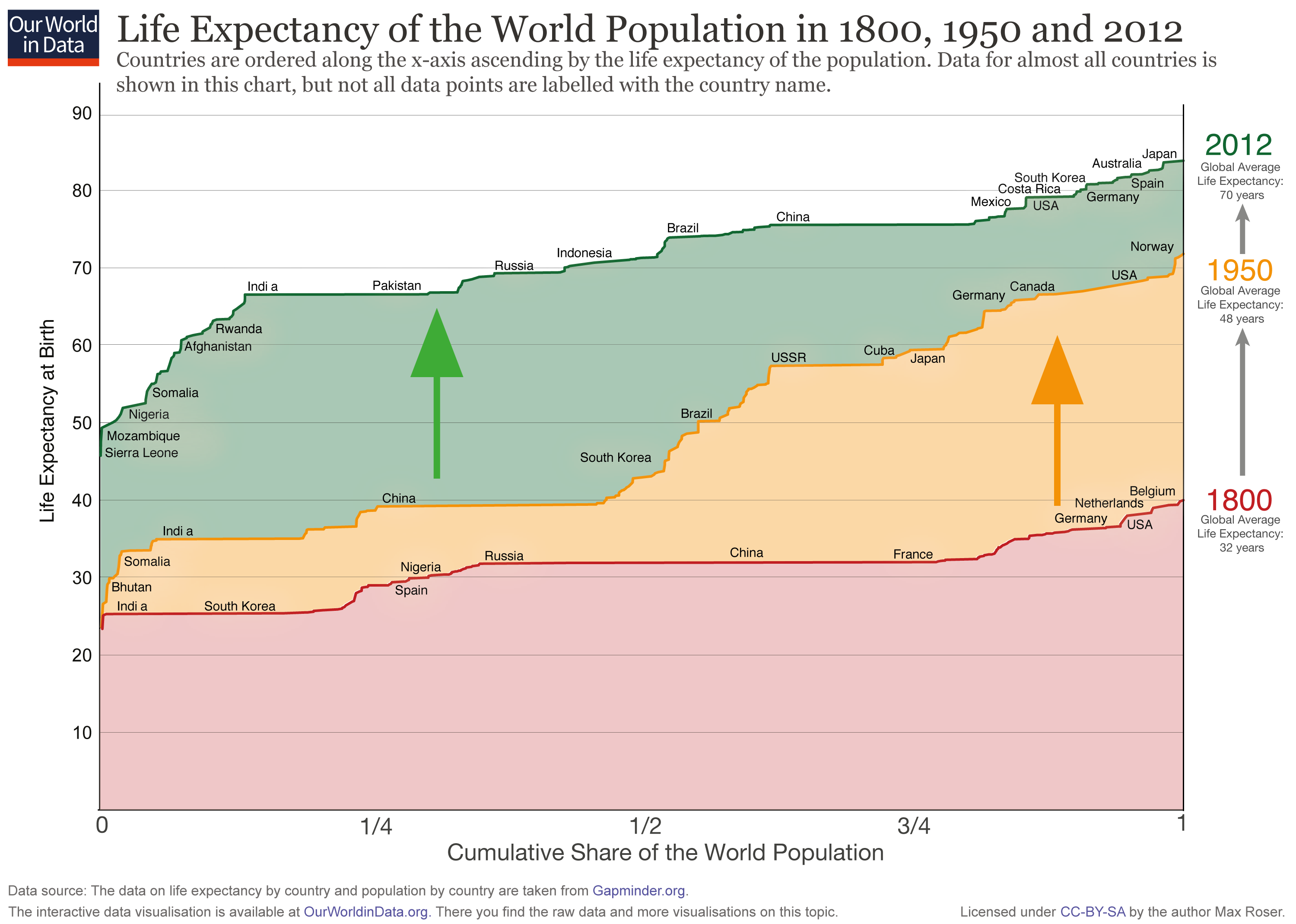

This chart shows the average life expectancy of different countries over time. It's laid out with the world's population on the horizontal axis and life expectancy on the vertical axis. Countries are arranged from lowest to highest life expectancy, and the width of each bar represents the size of that country's population.

Looking at the year 1800, shown by the red line, we can see countries like India and South Korea on the left, with life expectancies around 25 years. On the right-hand side, no country in 1800 had a life expectancy over 40 years; Belgium had the highest life expectancy, at 40 years.

By 1950, every country's life expectancy had increased compared to 1800. However, the gap between countries widened significantly. This was mainly because health improvements were more substantial in wealthier countries, particularly in Europe and North America, while countries like India and China saw limited progress.

The 2012 data, shown with a green line, shows further improvement: life expectancy rose across all countries, and the gap between them began to close. This change was driven by significant health advancements in poorer countries, which experienced very dramatic rises in life expectancy.

From 1800 to today, the world developed from equally poor health in 1800, to great inequality in 1950, and back to more equality today, by achieving higher life expectancy for all.

Life expectancy increased in all countries of the world

People in all countries are living longer than in the past.

In the long run the inequality in life expectancy within countries decreased hugely

Just as researchers can measure economic inequality with the Gini coefficient , this method can also be applied to assess the inequality of lifespans within a country.

The chart below uses the Gini coefficient to illustrate the inequality of lifetimes. A higher Gini coefficient indicates higher inequality of lifespans in the population – that some live much longer or shorter than the average person.

The process to calculate the Gini coefficient for lifespan inequality involves comparing the expected age at death of two individuals chosen at random from the population, and then repeating this comparison across all possible pairs. The total is then normalized to a scale from 0 to 1.

As the chart shows, lifespan inequality has declined over time in many countries. It also shows that wealthier nations generally exhibit lower levels of lifespan inequality.

Child mortality

In the previous section, we explored life expectancy at birth as a crucial overview of a population's overall health. Now, we turn our attention to the health outcomes of children.

Studying child mortality rates is vital for understanding the overall health of a country because the early years of life involve numerous health challenges. Children who survive these earliest years have a much higher life expectancy afterward. This is why a large part of the gains in life expectancy at birth historically were due to dramatic reductions in child mortality.

Child mortality measures the share of newborns who would not survive to their fifth birthday, given death rates at young ages in a population.

Find much more about the topic of child mortality on our dedicated page:

How has cross-country child mortality changed in the long run?

The interactive chart shows how child mortality has changed over the long run.

We can see significant improvements, especially in richer countries today, where child mortality rates have dropped to around 0.5% by 2021.

This dramatic decline, however, is a relatively recent phenomenon. Historically, in pre-modern societies, child mortality rates ranged between 30% and 50%. While health conditions for children in poorer countries are improving rapidly, their mortality rates are still substantially higher than those in richer countries.

Another notable aspect of the data shown in the chart is that there are many sharp ‘spikes’ in the 19th century. This is partly because the data quality is improving over time, but also because health crises were more frequent in pre-modern times, including food shortages, epidemics, and wars.

These crises significantly impacted living standards, which you can explore further on our page on food prices, which provides data and research on the frequency of food crises.

Food Prices

Food needs to be affordable for people, and at the same it is a key source of income for one-quarter of the world’s labor force.

You can also switch to the map view in this visualization, to compare child mortality rates across different countries and periods.

This comparison reinforces that all countries have experienced a reduction in child mortality rates over time. Yet there are still large disparities between richer and poorer countries, which highlights the ongoing challenge of closing the health gap.

Are poorer countries catching up with low child mortality rates in richer countries?

Over the past fifty years, poorer countries have made significant strides in reducing child mortality, which has helped narrow the gap between nations.

The chart below shows child mortality rates in countries of different income levels. We can see a consistent decline across all income levels.

There have been rapid advancements in low-income and upper-middle-income countries, and the gap between these countries and the rest of the world has been narrowing. Upper-middle-income countries are close to catching up.

Despite this progress, important challenges remain. On average, in 2021, low-income countries face child mortality rates that are more than ten times higher than those in high-income countries. The remaining gap is still large.

The most lethal infectious diseases over time

The chart shows the annual number of deaths from some of the most lethal infectious diseases among children.

As the chart shows, deaths caused by malaria and HIV/AIDS rose over the 1990s. From 2005 onwards, the number of deaths from these diseases has been declining.

Maternal mortality

Maternal mortality, like child mortality, serves as a critical indicator of a country's health status.

It refers to the deaths of women during pregnancy, or within 42 days of ending the pregnancy, with the rate often presented per 100,000 live births.

Find much more about the topic of maternal mortality on our dedicated page:

Maternal Mortality

What could be more tragic than a mother losing her life in the moment that she is giving birth to her newborn? Why are mothers dying and what can be done to prevent these deaths?

Maternal mortality has declined in the long run

Historical data on maternal mortality, particularly from high-income countries, shows significant reductions over time.

A century ago, maternal mortality rates ranged between 500 and 1,000 deaths per 100,000 live births. This means that, on average, for every 100 to 200 births, one resulted in the death of the mother. Since women in the past gave birth to more children than today, the deaths of mothers were a common tragedy.

Today, however, these rates have decreased to around 10 per 100,000 live births in those same countries.

This remarkable decline is largely due to advancements in medical science, particularly our understanding of hygiene's role in preventing puerperal fever, or childbed fever, a major cause of maternal deaths.

The discovery by Ignaz Semmelweis in the 19th century that hygiene could dramatically improve maternal survival was a turning point, but it was only after the germ theory of disease was established, that hygiene practices became widely adopted.

The pace of improvement in maternal mortality has varied by country.

For example, Finland began reducing its maternal mortality rates in the mid-19th century, but it took over a century to achieve today's low levels. Malaysia, on the other hand, saw similar improvements within just a few decades, which occurred much later.

How do countries compare on maternal mortality today?

Recent data on maternal mortality shows continuing improvements around the world, as the interactive chart below shows.

However, the challenges remain substantial, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa — where the rate in 2017 exceeded 500 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, more than 60 times the rate in the European Union.

Burden of disease

In the previous sections, we looked at health outcomes, measured only with data on mortality. But this doesn’t take into account the morbidity – the impact of disease on people alive.

The burden of disease is a related but different indicator of health outcomes, which accounts for both the mortality and the morbidity of disease.

The most common way to measure the burden of disease is to estimate the number of years of life “lost” due to poor health, which is the so-called loss in “Disability Adjusted Life Years” (DALYs).

DALYs are standardized units to measure lost health. They help compare the burden of different diseases in different countries, populations, and times.

Conceptually, one DALY represents one lost year of healthy life — it is the equivalent of losing one year in good health because of either premature death or disease or disability.

Burden of Disease

How is the burden of disease distributed and how did it change over time?

The global distribution of the disease burden

This map shows DALYs per 100,000 people in the population. It is thereby measuring the distribution of the burden of both mortality and morbidity around the world.

In some regions with the best health, the rate of DALYs was under 20,000 per 100,000 people in 2019. In contrast, in the worst-off regions, the rate was several times higher than that — over 60,000 in several countries in Africa.

Infectious diseases

The data shows that there are still major challenges regarding several diseases, including malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, diarrheal disease, and more.

Find much more about these topics on our dedicated pages:

A global epidemic and the leading cause of death in some countries.

The deadly disease transmitted by mosquitoes is one of the leading causes of death in children. How did we eliminate the disease in some world regions and how can we continue progress against malaria?

Diarrheal Diseases

Diarrheal diseases are one of the leading causes of child deaths while they are largely preventable. How can we continue to make progress against these diseases?

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is still among the most common causes of death globally. Explore global data on tuberculosis and its trends over time.

What explains changes and differences in health globally?

Health returns to healthcare investment, how strong is the link between healthcare expenditure and life expectancy.

Healthcare is a crucial factor affecting overall health outcomes. How much impact does it have? In this section, we’ll look at how healthcare is related to health outcomes, such as life expectancy.

Find much more about healthcare spending on our dedicated page:

In the chart below, we can see a comparison between life expectancy and per capita healthcare expenditure across countries. The chart shows the change between 1995 and the latest year.

The data reveals a clear trend — countries with higher healthcare spending per capita generally exhibit longer life expectancy. By looking at the change over time, we can also see that, as countries spend more on health, the population’s life expectancy increases.

But the benefits of increased healthcare spending are affected by “diminishing returns”. This means that, as spending levels continue to rise, countries receive less “bang for their buck” – the health gains per dollar spent decline.

This effect is larger in wealthier countries, which suggests that lower-income countries, which have low initial spending, can substantially improve life expectancy by making relatively modest increases in healthcare spending.

The link between health spending and increasing life expectancy is also visible in rich countries in Europe, Asia, and North America in the upper right corner of the chart.

But the chart also shows significant regional differences — countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have made remarkable progress in life expectancy following increased health investments, for example.

How strong is the link between healthcare expenditure and child mortality?

The chart below shows how healthcare spending is related to child mortality, in the same format.

By connecting data points between 1995 and 2014 with arrows for each country, the chart shows a global trend: as healthcare spending increases, child mortality rates decline.

This trend shows the positive impact of health investments on reducing child mortality across the world, highlighting the crucial role of healthcare expenditure in improving child health outcomes.

You can also see there is a stark disparity in healthcare spending globally — such as the extreme difference between countries like the Central African Republic, where healthcare spending per capita was less than 100 international dollars in 2019, and the United States, where it was higher than 10,000 international dollars. This is a very large gap, considering that these numbers are adjusted for price differences between countries.

But despite this, the decline in child mortality relative to health expenditure is surprisingly consistent across countries.

This uniformity in trends, regardless of a country's wealth, suggests a consistent benefit of increased healthcare spending on reducing child mortality.

However, the enormous gap in healthcare expenditure, where Americans spend more on health within three days than a person in the Central African Republic does in a year, also highlights the remaining challenges of global health inequality.

How strong is the link between healthcare expenditure and national income?

The strongest predictor of a country's healthcare spending is its national income.

Countries with a higher per capita income tend to spend more on healthcare, which you can see in the chart below. 2

Advanced economic research shows that this relationship is not just a correlation: there is a clear and significant positive effect of per capita GDP on healthcare spending. 3

The finances of healthcare

In the previous section, we looked at the evidence supporting the fact that there are potentially large health returns to healthcare investment.

Here we look at how healthcare investments are financed around the world.

When did high-income countries start expanding their healthcare systems?

The earliest data on the financing of healthcare dates back to the late 19th century. This is when many European countries began officially establishing healthcare systems through legislative acts.

The chart here shows estimates of government spending on healthcare as a percent of GDP, for a selection of high-income countries using data from multiple sources.

You can see that healthcare spending has risen substantially over time.

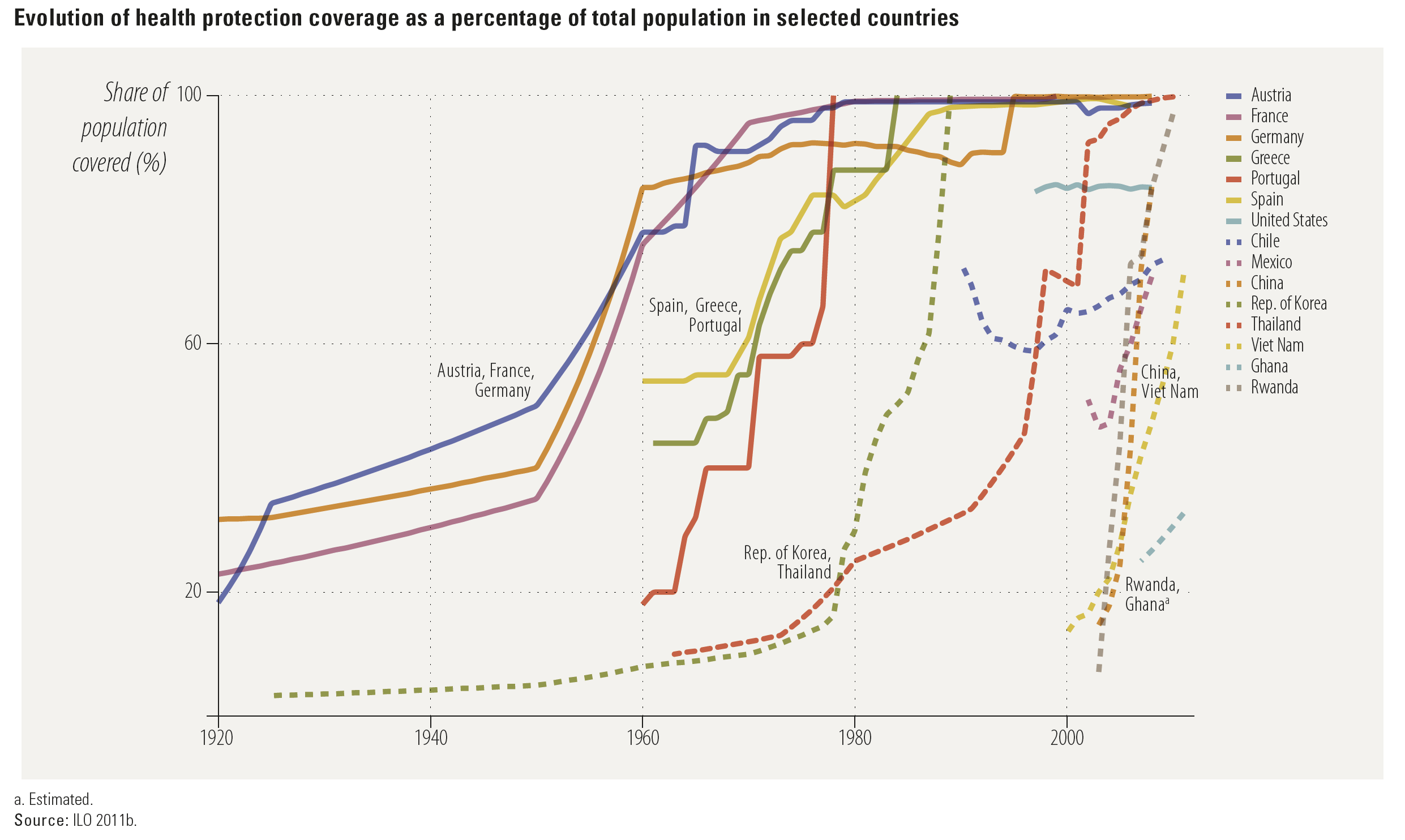

How quickly can healthcare coverage expand?

European countries led the expansion of healthcare systems in the early 20th century — countries like France, Austria, and Germany expanded healthcare coverage between 1920 and 1960 — followed by Spain, Portugal, and Greece between 1960 and 1980.

In contrast, China, Rwanda, and Vietnam rapidly developed their healthcare systems in the 21st century, almost from scratch, achieving near-universal coverage within just a decade. This demonstrates that significant improvements in healthcare protection can be achieved quickly, even from low starting points.

How has global expenditure on healthcare changed in recent decades?

In recent decades, spending on healthcare has been relatively stable in countries. But there are very large differences in the level of spending between countries.

This is shown in the chart below.

How important is out-of-pocket spending around the world?

Out-of-pocket spending — direct payments to healthcare providers by households — varies significantly around the world.

In richer countries like France, it represents a small fraction of total healthcare expenditure. But in poorer countries, such as Afghanistan and Nigeria, it can be the majority of healthcare spending.

While many countries, especially in the developing world, have made progress in reducing out-of-pocket expenses, others like Russia have seen these costs increase.

Healthcare coverage

Coverage of essential health services is increasing.

Essential health services are a range of basic health provisions, such as vaccination, detection and treatment of tuberculosis (TB), HIV treatment, pregnancy care, sanitation, and access to medicines.

In the following charts, we’ll look at global trends in these different areas.

In general, there has been a rise in global coverage of essential health services since 2000. But some health services see a much steeper rise — due to specific efforts against diseases.

For example, efforts against against HIV, TB, and malaria have risen substantially, through programs such as The Global Fund and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief ( PEPFAR ).

Vaccination coverage has also seen a considerable increase since 2000. This rise has been even more significant across particular regions.

In many African countries, for example, vaccination coverage has increased rapidly since 2000 — this is a strong reflection of increased funding from Gavi, the vaccine alliance , the United Nations, and additional donor funds.

Read more on our page:

Vaccination

Vaccines are key in making progress against infectious diseases and save millions of lives every year.

In the chart below, you can see rises in detection rates for tuberculosis in different countries. This is again helped by efforts such as The Global Fund and PEPFAR.

In the chart below, you can see the rise in the share of people with HIV who receive antiretroviral therapy, a lifesaving intervention against HIV/AIDS .

In the map, you can see coverage for antenatal care, which have been slower and remain at low levels in many countries.

In the chart below, you can see share who use safely-managed sanitation, which has risen gradually over time.

Even now, large disparities remain. A large share of people in many countries still don’t have access to, or use, safely-managed sanitation.

Clean Water and Sanitation

Explore global usage of clean water and sanitation.

Medicine availability in developing countries remains a barrier to affordable medicine access

To ensure people have access to essential medicines, medicines must be available and affordable.

But the availability of medicines is much lower in the public sector of poorer countries. Even in the private sector, where availability is higher, there is still a lack of consistent access. 5

This has important implications for access to essential medicines — especially for the poorest. Most health facilities in the public sector offer medicines at low cost or free of charge, so are essential in healthcare provision for the poor. When medicines are not available in the public sector, people try to access them privately, which is typically more expensive and unaffordable for many.

This is important because people in poorer countries have higher price sensitivity to medicines, and even minimal costs can significantly reduce people’s use of essential healthcare products.

Interactive charts on global health

The data on life expectancy is taken from Version 7 of the dataset published by Gapminder . The data on the population of each country is also taken from Gapminder.

The included world population in 1800 is 1,036 billion. In 1950 it is 2,72 billion. And for 2012 it is the life expectancy of that year and the population measures refer to 2010 (7 billion people are included in this analysis).

Newhouse, J.P. (1977), “Medical care expenditure: a cross-national survey”, Journal of Human Resources 12:115–125.

Interestingly, there are important institutional variables that are also significantly correlated with healthcare expenditure after controlling for income. For example, the use of primary care “gatekeepers” seems to result in lower health expenditure. And lower levels of health expenditure also appear to occur in systems where the patient first pays the provider and then seeks reimbursement, compared to other systems. For more information see page 46 in Culyer, A. J., & Newhouse, J. P. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of health economics . Elsevier.

The source given for the data corresponds to Figure 1 in ILO, (2011), Social Protection Floor for a Fair and Inclusive Globalization. Report of the Advisory Group chaired by Michelle Bachelet convened by the ILO with the collaboration of the WHO. Geneva: International Labour Office. Available online here .

United Nations (2008). Delivering on the Global Partnership for Achieving the Millennium Development Goals. MDG Gap Task Force Report 2008. Available online .

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

Global Observatory on Health R&D: Bridging the Gap in Global Health Research and Development

The World Health Organization's Global Observatory on Health Research and Development (R&D) has released its latest findings, revealing stark disparities in global health research funding, resource allocation, and capacity between high-income and low- and middle-income countries. The commentary “ Tracking global resources and capacity for health research: time to reassess strategies and investment decisions ” published in Health Research Policy and systems in September 2023 sheds light on the critical need to reassess strategies and investment decisions in health R&D.

Addressing historical inequities

The COVID-19 pandemic and recent outbreaks like mpox underscore the urgency and importance of enhancing the availability and equitable distribution of resources for health research worldwide. Despite previous discussions and recommendations, little progress has been made in rectifying the imbalances in resource allocation for health research between affluent and less affluent nations. This issue is crucial not only for emergency preparedness but also for the global mission to improve population health equitably.

Recognizing the lack of advancement in this area, Member States of the World Health Organization called for the establishment of the Global Observatory on Health Research and Development which was launched in January 2017. Its primary objective is to consolidate, monitor, and analyze pertinent information on health R&D to inform the coordination and prioritization of new investments.

Key findings from the Observatory

The commentary highlights four key areas of concern based on the Observatory's analysis over the 5 years since its inception in 2017:

- Grant funding disparities: The analysis of grants for health research by major international funders in 2020 showed that low-income countries received only 0.2% of all grant funding. Only 0.2% of all grant funding for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) was allocated to institutions in low- and middle-income countries. Funding for priority areas like neglected tropical diseases remained at 0.6%.

- Human resource disparities: High-income countries had approximately 56 times more health researchers per million inhabitants than low-income countries, perpetuating the inequality in research capacity.

- Higher education opportunities: Low-income countries had the fewest higher education institutions per million people compared to other income groups, limiting opportunities for research training.

- Meeting global R&D targets: Many countries failed to meet the recommended targets for health R&D expenditures as a percentage of GDP or the allocation of official development assistance to medical research.

The need for action

The findings underscore the persistent disparities in health research funding and capacity. Despite decades of recognition, progress remains elusive. To address these issues, the commentary calls for:

Systematic data collection: Countries must routinely collect data to track health R&D indicators.

Research prioritization: Funders of health R&D should prioritize research that aligns with both global and local public health needs.

Data sharing: More data sharing is essential, particularly from low- and middle-income countries, to enable better coordination and informed decisions.

Global cooperation: The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the opportunity for global cooperation and action to create a more equitable future in global health research and development.

The Global Observatory on Health R&D continues to serve as a comprehensive platform to track and analyze health R&D data, providing critical insights into the progress and challenges in this vital field. With concerted effort, the global community can bridge the gap in health research and development, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes for all.

For more information and to access the full version of the analysis mentioned in the commentary , please visit the Global Observatory on Health Research and Development.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Global Health Research Topics

Subscribe to Fogarty's Global Health Matters newsletter , and weekly funding news for global health researchers .

The Fogarty International Center and its NIH partners invest in research on a variety of topics vital to global health. For each of these global health research topics, find an in-depth collection of news, resources and funding from Fogarty, the NIH, other U.S. government agencies, nongovernmental organizations and others.

- Chronic noncommunicable diseases (NCDs)

- Climate change

- Deafness and other communication disorders

- Diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility

- Eye disease, vision health and blindness

- Global health security

- Household air pollution

- Implementation science

- Infectious diseases

- Coronaviruses

- Ebola virus disease

- Tuberculosis (TB)

- Vector-borne diseases (malaria, dengue, Zika, etc.)

- Maternal and child health

- Mentoring and mentorship training

- Mobile health (mHealth)

- Neurological and mental disorders and diseases

- Oral and dental health

- Trauma and injury

- Tobacco control

- Women’s leadership in global health research

Health Topic Information

- NIH Health Topics

- MedlinePlus Health Topics

- Diseases and Conditions from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Updated January 3, 2024

Global Health Research and Policy

- Most accessed

Challenges associated with the implementation of institutional quarantine and isolation strategies during major multicountry viral outbreaks in Africa (2000–2023): a scoping review

Authors: Jimoh Amzat, Ebunoluwa Oduwole, Saheed Akinmayowa Lawal, Olusola Aluko-Arowolo, Rotimi Afolabi, Isaac Akinkunmi Adedeji, Ige Angela Temisan, Ayoyinka Oludiran, Kafayat Aminu, Afeez Abolarinwa Salami and Kehinde Kazeem Kanmodi

How to leverage implementation research for equity in global health

Authors: Olakunle Alonge

Uptake of biosimilars in China: a retrospective analysis of the case of trastuzumab from 2018 to 2023

Authors: Qiyou Wu, Zhitao Wang, Yihan Fu, Ren Luo and Jing Sun

From silos to synergy: a consortium approach to air pollution and public health in Abu Dhabi

Authors: Barrak Alahmad, Ernani F. Choma, Basem Al-Omari, Eman Alefishat, Abdu Adem, John S. Evans, Petros Koutrakis and Senthil Rajasekaran

The gender gap in outpatient care for non-communicable diseases in Mexico between 2006 and 2022

Authors: Edson Serván-Mori, Ileana Heredia-Pi, Carlos M. Guerrero-López, Stephen Jan, Laura Downey, Rocío Garcia-Díaz, Gustavo Nigenda, Emanuel Orozco-Núñez, María de la Cruz Muradás-Troitiño, Laura Flamand, Robyn Norton and Rafael Lozano

Most recent articles RSS

View all articles

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on firms: a survey in Guangdong Province, China

Authors: Peng Zou, Di Huo and Meng Li

Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: a global challenge

Authors: Bei Wu

The novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China

Authors: Hengbo Zhu, Li Wei and Ping Niu

Factors affecting access to primary health care services for persons with disabilities in rural areas: a “best-fit” framework synthesis

Authors: Ebenezer Dassah, Heather Aldersey, Mary Ann McColl and Colleen Davison

What is global health? Key concepts and clarification of misperceptions

Authors: Xinguang Chen, Hao Li, Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno III, Abu S. Abdullah, Jiayan Huang, Charlotte Laurence, Xiaohui Liang, Zhenyu Ma, Zongfu Mao, Ran Ren, Shaolong Wu, Nan Wang, Peigang Wang, Tingting Wang, Hong Yan and Yuliang Zou

Most accessed articles RSS

Wuhan University Elected as the Chair Institution of Chinese Consortium of Universities for Global Health (2022-2023)

Aims and scope

Global Health Research and Policy is an open access, multidisciplinary journal that publishes topic areas and methods addressing global health questions. These include various aspects of health research, such as health equity, health systems and policy, social determinants of health, disease burden, population health and other urgent and neglected global health issues.

Global Health Research and Policy aims to provide a forum for high quality researches on exploring regional and global health improvement and the solution for health equity.

Latest Collections

Global Health Education in China Guest edited by Dr. Yuantao HAO, Dr. Dong XU, Dr. Jing GU, Dr. Chun HAO, Dr. Brian J. Hall

The Governance of New Coronavirus Pandemic: Bridging Research and Policy Guest edited by Prof. Hao Li, Prof. Xinguang Chen, Prof. Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno III, Prof. Abu S. Abdullah

China-UK Joint Contribution to Global Health: Selected GHSP Findings and Policy Implications Guest edited by Dr. Hao Li, Ms Xiaohua Wang, Dr. Charlotte Laurence and Prof. Tongwu Xu

Universal Health Coverage Guest Edited by Dr. Beibei Yuan, Dr. Lanting Lu and Dr. Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno III

Senior editorial team

Editors-in-Chief Zongfu Mao, School of Public Health/Global Health Institute, Wuhan University, China Hao Li, School of Public Health/Global Health Institute, Wuhan University, China

Deputy Editors-in-Chief Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno III, Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK Jiayan Huang, School of Public Health, Fudan University, China Dong (Roman) Xu, Southern Medical University, China

Managing Editor Xinliang Liu, School of Public Health/Global Health Institute, Wuhan University, China

Administrative Editor Nan Wang, School of Public Health/Global Health Institute, Wuhan University, China

Assistant Editor Jiaxin He, School of Public Health/Global Health Institute, Wuhan University, China

- Editorial Board

- Manuscript editing services

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

Annual Journal Metrics

Citation Impact 2023 Journal Impact Factor: 4.0 5-year Journal Impact Factor: 4.8 Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP): 1.377 SCImago Journal Rank (SJR): 1.514

Speed 2023 Submission to first editorial decision (median days): 14 Submission to acceptance (median days): 202

Usage 2023 Downloads: 545,373 Altmetric mentions: 557

- More about our metrics

ISSN: 2397-0642

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

This is why nih invests in global health research, nih blog post date, connect with us.

- More Social Media from NIH

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

HRI brings more than twenty years of experience in scientific research in clinical health settings and public health. We conduct field epidemiological studies and secondary analyzes of data, observational studies, surveys, and clinical trials.

High-quality research is essential to fulfilling WHO’s mandate for the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health. One of the Organization’s core functions is to set international norms, standards and guidelines, including setting international standards for research.

For general inquiries about international health research: Please contact the NCCIH Division of Extramural Research at [email protected]. Identifies promising international complementary and integrative practices and encourages their rigorous scientific assessment.

The Department of International Health is organized into four program areas: Global Disease Epidemiology and Control; Health Systems; Human Nutrition; and Social and Behavioral Interventions. We offer a Master of Science in Public Health (MSPH) and doctoral-level training for research (PhD) in these program areas, as well as a Master of Health ...

WHO has three key objectives to promote forward-looking and prioritized global health research: Anticipating scientific, technological, and epidemiological shifts.

On this page, we provide an overview of global health, emphasizing data on health outcomes – such as disease and death – and the effects of healthcare investments. We begin by examining life expectancy, a primary indicator of population health.

The World Health Organization's Global Observatory on Health Research and Development (R&D) has released its latest findings, revealing stark disparities in global health research funding, resource allocation, and capacity between high-income and low- and middle-income countries.

For each of these global health research topics, find an in-depth collection of news, resources and funding from Fogarty, the NIH, other U.S. government agencies, nongovernmental organizations and others.

Global Health Research and Policy is an open access, multidisciplinary journal that publishes topic areas and methods addressing global health questions. These include various aspects of health research, such as health equity, health systems and policy, social determinants of health, disease burden, population health and other urgent and ...

At NIH, the Fogarty International Center helps the other institutes become engaged with global health research, which investigates the dual burden of infectious disease and non-communicable disease. Global health research also encompasses data science, economics, genetics, climate change science, and many other disciplines.