MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

World War II: Posters and Propaganda

By tim bailey, unit objective.

This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman’s series of Common Core State Standards–based teaching resources. These units were written to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts of historical significance. The lessons are built around the use of textual and visual evidence and critical thinking skills.

Over the course of three lessons the students will analyze a secondary source document and primary source documents in the form of propaganda posters produced to support the United States war effort during World War II. These period posters represent the desire of the government to gain support for the war by shaping public opinion. Students will closely analyze both the primary source artwork and the secondary source essay with the purpose of not only understanding the literal meaning but also inferring the more subtle messages. Students will use textual and visual evidence to draw their conclusions and present arguments as directed in each lesson.

In this lesson the students will carefully analyze an essay that discusses both the purpose and the impact of World War II posters on the American war effort on the home front. This essay will give the students background knowledge that will make close analysis of the actual posters more effective over the next two lessons. A graphic organizer will be used to help facilitate and demonstrate their understanding of the essay.

Introduction

With the attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States found itself suddenly involved in a war that was raging across nearly every continent of the globe. As the American military ramped up its war effort, support from the American public became crucial. The need for more soldiers, more factory production, more government funds, and less consumption by civilians of crucial war resources led to a public propaganda campaign. In an age before the widespread use of television the two best ways to reach the public were radio broadcasts and print. President Roosevelt was a pioneer in using the radio to sway public opinion, and soon colorful posters promoting the requirements of the war effort began appearing all over the United States.

- "Every Citizen a Soldier: World War II Posters on the American Home Front," by William L. Bird Jr. and Harry Rubenstein (abridged from The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History website; complete essay is here )

- Graphic Organizer: Every Citizen a Soldier: World War II Posters on the American Home Front

At the teacher’s discretion you may choose to have the students do the lesson individually, as partners, or in small groups of no more than three or four students.

- Hand out "Every Citizen a Soldier: World War II Posters on the American Home Front," by William L. Bird Jr. and Harry Rubenstein.

- "Share read" the essay with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a few sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English language learners (ELL).

- Hand out Graphic Organizer Lesson 1: Every Citizen a Soldier: World War II Posters on the American Home Front.

- Using the graphic organizer, the students analyze the secondary source document. This can be done as a whole-class activity with discussion, in small groups, with partners, or individually.

- Discuss different interpretations developed by the students or student groups.

In this lesson the students will carefully analyze ten primary source posters from World War II. These posters come from a variety of sources but all of them reflect the themes developed by the United States government and the Office of War Information (OWI). These themes were introduced in the essay used in lesson one. The students will determine which of the six themes recommended by the OWI the poster best represents. They will use the visual evidence as well as the textual evidence to analyze the theme presented in the poster. A poster analysis sheet will be used to demonstrate their understanding.

The development of posters to promote American patriotism during World War II is an example of propaganda. Propaganda is a form of communication that usually bypasses the intellect and motivates a target group by appealing to their emotions. The posters developed for the home front during World War II were designed to motivate American citizens and develop a sense of patriotism that would turn the United States into an unstoppable war machine. These posters called on all Americans to be part of the war effort, not just by carrying a gun into battle, but in many other important ways. Government programs such as metal and rubber drives may not have meant the difference between winning or losing the war, but the camaraderie and sense of unity generated by such drives was very important to the war effort.

- World War II Posters #1–#10

- Analyzing the Poster (each student or group will need five copies)

- Hand out World War II Posters #1–#2 and Analyzing the Poster

- The students answer the questions on the Analyzing the Poster handouts for each poster. For the first two posters this will be done as a whole-class activity with discussion. After analyzing the first two posters with the class, hand out posters #3–#10. These posters will be analyzed by the students in small groups, with a partner, or individually.

- Discuss different interpretations developed by the students or student groups. Discuss the information in the introduction.

In this lesson the students will carefully analyze ten primary source posters from World War II. The students will determine which of the six themes recommended by the Office of War Information the poster best represents. The students will use the visual evidence, as well as the textual evidence, in order to analyze the theme presented in each poster. A poster analysis sheet will be used to demonstrate their understanding. In addition, the students will synthesize, analyze, and present an argument about what they have learned in a short essay.

In 1942 President Franklin Roosevelt created the Office of War Information to distribute and control pro-American propaganda during World War II. To accomplish this goal the Office of War Information recruited Hollywood movie studios, radio stations, and the print media. In a general sense, the goal of this effort was to promote hatred for the enemy, support for America’s allies, and a greater support for the war by the American public through increased production, victory gardens, scrap drives, and the buying of US War Bonds. Of all the propaganda produced during the war, the posters had the widest national reach, with more than 200,000 different types produced during the war.

- World War II Posters #11–#20

- World War II Posters and Propaganda Essay Form

At the teacher’s discretion you may choose to have the students do the lesson individually, as partners, or in small groups of no more than three or four students.

- Hand out World War II Posters #11–#20 and Analyzing the Poster.

- The students analyze the posters and answer the questions on the worksheet.

- Discuss different interpretations developed by the students or student groups and the information in the introduction.

- Hand out the essay form. Students will answer the prompt in a short argumentative essay that uses what they have learned from their analysis of the posters. This assignment should be done individually.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? Analyzing World War II Posters

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

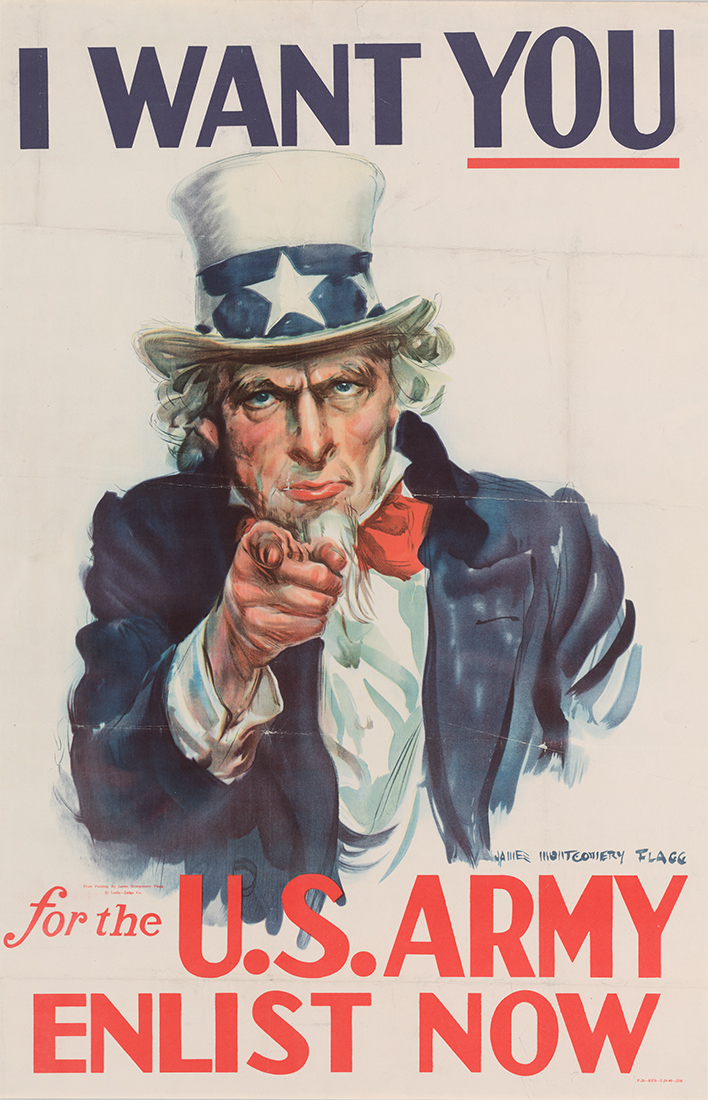

In this lesson plan, students analyze World War II posters, chosen from online collections, to explore how argument, persuasion and propaganda differ. The lesson begins with a full-class exploration of the famous "I WANT YOU FOR U.S. ARMY" poster, wherein students explore the similarities and differences between argument, persuasion, and propaganda and apply one of the genres to the poster. Students then work independently to complete an online analysis of another poster and submit either an analysis worksheet or use their worksheet responses to write a more formal essay.

Featured Resources

- Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? : This handout clarifies the goals, techniques, and methods used in the genres of argument, persuasion, and propaganda.

- Analyzing a World War II Poster : This interactive assists students in careful analysis of a World War II poster of their own selection for its use of argument, persuasion, or propaganda.

From Theory to Practice

Visual texts are the focus of this lesson, which combines more traditional document analysis questions with an exploration of World War II posters. The 1975 "Resolution on Promoting Media Literacy" states that explorations of such multimodal messages "enable students to deal constructively with complex new modes of delivering information, new multisensory tactics for persuasion, and new technology-based art forms." The 2003 "Resolution on Composing with Nonprint Media" reminds us that "Today our students are living in a world that is increasingly non-printcentric. New media such as the Internet, MP3 files, and video are transforming the communication experiences of young people outside of school. Young people are composing in nonprint media that can include any combination of visual art, motion (video and film), graphics, text, and sound-all of which are frequently written and read in nonlinear fashion." To support the literacy skills that students must sharpen to navigate these many media, activities such as the poster analysis in this lesson plan provide bridging opportunities between traditional understandings of genre and visual representations. Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

- Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda?

- Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda

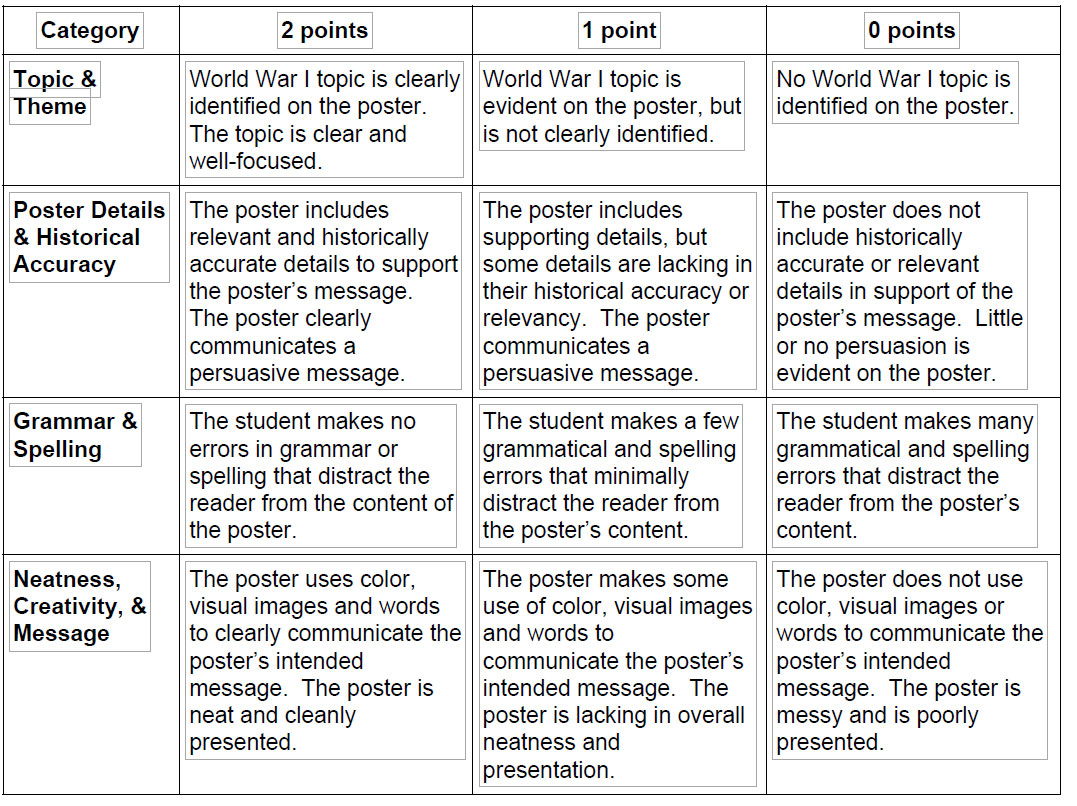

- Poster Analysis Rubric

Preparation

- Make appropriate copies of Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? , Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda , and Poster Analysis Rubric .

- Explore the background information on the Uncle Sam recruiting poster , so that you are prepared to share relevant historical details about the poster with students.

- If desired, explore the online poster collections and choose a specific poster or posters for students to analyze. If you choose to limit the options, post the choices on the board or on white paper for students to refer to in Session Two .

- Decide what final product students will submit for this lesson. Students can submit their analysis printout from the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive, or they can write essays that explain their analysis. If students write essays, the printouts from the interactive serve as prewriting and preparation for the longer, more formal piece.

- Test the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive and the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive on your computers to familiarize yourself with the tools and ensure that you have the Flash plug-in installed. You can download the plug-in from the technical support page.

Student Objectives

Students will

- discuss the differences between argument, persuasion, and propaganda.

- analyze visual texts individually, in small groups, and as a whole class.

- (optionally) write an analytical essay.

Session One

- Display the Uncle Sam recruiting poster using an overhead projector.

- Ask students to share what they know about the poster, noting their responses on the board or on chart paper.

- If students have not volunteered the information, provide some basic background information .

- Working in small groups, have students use the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive to analyze the Uncle Sam poster.

- Emphasize that students should use complete, clear sentences in their responses. The printout that the interactive creates will not include the questions, so students responses must provide the context. Be sure to connect the requirement for complete sentences to the reason for the requirement (so that students will understand the information on the printout without having to return to the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive.

- As students work, encourage them to look for concrete details in the poster that support their statements.

- Circulate among students as they work, providing support and feedback.

- Once students have completed the questions included in the Analyzing a Visual Message interactive, display the poster again and ask students to share their observations and analyses.

- Emphasize and support responses that will tie to the next session, where students will complete an independent analysis.

- Pass out and go over copies of the Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda Chart .

- Ask students to apply genre descriptions to the Uncle Sam poster, using the basic details they gathered in their analysis to identify the poster's genre.

Session Two

- Review the Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda? chart.

- Elicit examples of argument, persuasion, and propaganda from the students, asking them to provide supporting details that confirm the genres of the examples. Provide time for students to explore some of the Websites in the Resources section to explore the three concepts.

- When you feel that the students are comfortable with the similarities and differences of the three genres, explain to the class that they are going to be choosing and analyzing World War II posters for a more detailed analysis.

- Pass out the Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda , and go over the questions in the analysis sheet. Draw connections between the questions and what the related answers will reveal about a document's genre.

- Demonstrate the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive.

- Point out the connections between the questions in the interactive and the questions listed on the Document Analysis for Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda .

- If students need additional practice with analysis, choose a poster and use the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive to work through all the analysis questions as a whole class.

- Explain the final format that students will use for their analysis—you can have students submit their analysis printout from the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive, or they can submit polished essays that explain their analysis.

- Pass out copies of the Poster Analysis Rubric , and explain the expectations for the project.

- Posters on the American Home Front (1941-45), from the Smithsonian Institute

- Powers of Persuasion, from the National Archives

- World War II Poster Collection, from Northwestern University

- World War II Posters, from University of North Texas Libraries

Session Three

- Review the poster analysis project and the handouts from previous session.

- Answer any questions about the Analyzing a World War II Poster interactive then give students the entire class session to work through their analysis.

- Remind students to refer to the Poster Analysis Rubric to check their work before saving or printing their work.

- If you are having students submit their printouts for the final project, collect their work at the end of the session. Otherwise, if you have asked students to write the essay, ask them to use their printout to write the essay for homework. Collect the essays and printouts at the beginning of the next session (or when desired).

- If desired, students might share the posters they have chosen and their conclusions with the whole class or in small groups.

The Propaganda Techniques in Literature and Online Political Ads lesson plan offers additional information about propaganda as well as some good Websites on propaganda.

Student Assessment / Reflections

Use the Poster Analysis Rubric to evaluate and give feedback on students’ work. If students have written a more formal paper, you might provide additional guidelines for standard written essays, as typically used in your class.

- Calendar Activities

- Professional Library

- Strategy Guides

- Lesson Plans

This resolution discusses that understanding the new media and using them constructively and creatively actually requires developing a new form of literacy and new critical abilities "in reading, listening, viewing, and thinking."

This strategy guide clarifies the difference between persuasion and argumentation, stressing the connection between close reading of text to gather evidence and formation of a strong argumentative claim about text.

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

American Social History Project · Center for Media and Learning

Propaganda and world war ii.

In this activity, students compare World War II propaganda posters from the United States, Great Britain, Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union. Then students choose one of several creative or analytical writing assignments to demonstrate what they've learned.

Students will understand how waging a "total war" altered the nature of American society.

Students will read, write, listen, and speak for critical analysis and evaluation.

Students will understand the effects of World War II at home.

Instructions

Step 1: Poster Analysis

Before the lesson begins, the teacher should prepare packets of posters for each nation: United States, Great Britain, Nazi Germany, and Soviet Union.Â

Divide students into small groups of 3-4 students. Assign each group one of the four nations and pass out the packets to the appropriate groups. Each student should choose one poster from the packet to analyze, using the Poster Analysis Worksheet.Â

After individually analyzing posters, the groups should reconvene. Each group member should present their poster to their group members. After presentations, group members should discuss how they feel the posters work together: Is there a common theme? Are there common images? What aspects of the posters make them propaganda?

Step 2: Essay Writing

After the group discussion, students should individually write an essay about the posters. The teacher may choose one assignment from the list below or allow students to choose from among the options; the teacher may also differentiate the lesson by varying which assignment is given to each student:

Compare and contrast two or more posters

Visual essay: pull together different images to tell a story; text should bridge the posters together

Responsive essay: elaborate on the emotions (anger, sadness, pride, etc.) that the poster(s) evoke

Historial writing: Historically contextualize the poster: Is there a particular event or person the poster refers to? What makes this a World War II poster? (Requires additional research)

Point of view writing: Pretend you are a person in the poster; what story do you want to convey?

Fiction writing: Make up a narrative describing the events leading up to or following the scene depicted in the poster

Historical Context

Propaganda was one of many weapons used by many countries during World War II, and the United States was no exception. From posters to films and cartoons, the federal government used propaganda not only to buoy the spirit and patriotism of the home front, but also to promote enlistment in the military and labor force. Several government agencies were responsible for producing propaganda, with the largest being the Office of War Information (OWI), created in 1942. The OWI created posters, worked with Hollywood in producing pro-war films, wrote scripts for radio shows, and took thousands of photographs that documented the war effort. Worried by the increase in government sponsored propaganda, academics and journalists established the Institute for Propaganda Analysis. The Institute identified seven basic propaganda devices: Name-Calling, Glittering Generality, Transfer, Testimonial, Plain Folks, Card Stacking, and Band Wagon. [For more on the IPA and the seven devices, please see http://www.propagandacritic.com/] All of these devices were used during the war. In this activity, students will analyze World War II posters, examining the different techniques and themes used by the OWI and other branches of government.

Materials for this Activity

"I'm Proud... My Husband Wants Me To Do My Part"

"We Can Do It!"

"Pvt. Joe Louis Says - We're Going to do our part"

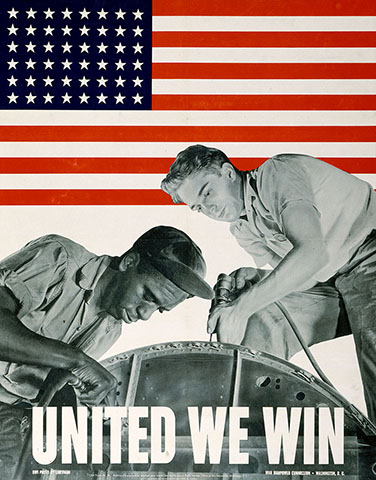

"United We Win"

"Someone Talked"

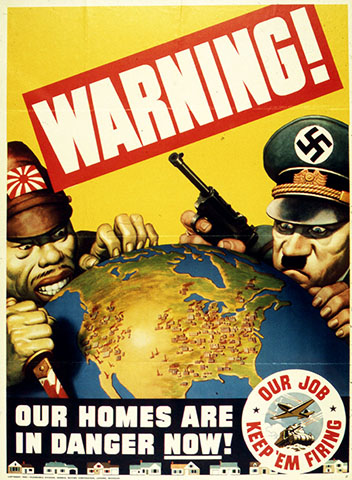

"Warning! Our Homes Are in Danger Now!"

A Black Candidate Runs on Civil Rights in 1940s New York

Up Housewives and At 'Em!

Dig for...Plenty

Keep Mum, She's Not So Dumb!

They Can't Get on Without Us

"Altpapiersammlung (Paper Drive)"

"Nicht spenden, Opfern (Don't give, Sacrifice)"

"We will ruthlessly defeat and destroy the enemy!"

"Du Bist Front (You Are the Front)"

"Death to the Fascist Reptile!"

"Der Jude (The Jew)"

"Red Army man, come to the rescue!"

"On the Joyous Day of Liberation from under the Yoke of the German Invaders"

Propaganda Poster Analysis Worksheet

Historical Era

Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Group Work , Interdisciplinary , Lessons in Looking , Making Connections , World War II

You might also like

"Operating a hand drill at Vultee-Nashville"

A World War II Soldier Finds Segregation on Army Bases

"Jenny on the Job Gets Her Beauty Sleep"

"Americans all, let's fight for victory: Americanos todos, luchamos por la victoria"

Print and Share

world war ii propaganda

All Formats

Resource types, all resource types.

- Rating Count

- Price (Ascending)

- Price (Descending)

- Most Recent

World war ii propaganda

WWII Propaganda Posters Activities and Project Print & Digital

- Google Apps™

Nazi Propaganda Reading Comprehension Worksheet World War II (2) Holocaust

World War II Disney Cartoons Propaganda Analysis (Disney films)

- Google Drive™ folder

- Internet Activities

Analyzing Propaganda from World War Two (WW2) - Lesson, PowerPoint, Assignments

WW2 - Propaganda Analysis

- Word Document File

WWII Propaganda Escape Room

World War I and World War II Propaganda Poster

WWII Propaganda Poster Analysis

5.20 WWII Propaganda Poster Analysis Activity with PowerPoint

World War 2 Propaganda Primary Source DBQ: How was propaganda used?

World War Two (WWII) - Analyzing Propaganda Source Analysis

World War II Propaganda Posters WWII Project

Nazi Propaganda PowerPoint Presentation World War 2 WWII

Disney World War Two Propaganda Video Questions

US Propaganda in World War II ( WWII )-- Lesson, activity and writing assignment

WWII Life at Home Propaganda Analysis - Google Slides, Discussion, and Activity

- Google Slides™

WWII American Homefront Propaganda Poster Analysis (Stations/Gallery Walk)

World War 2 Propaganda and Political Cartoons Activities

- Easel Activity

ESCAPE ROOM: WWII Propaganda - Google Classroom Version

Propaganda - Nazi posters during World War II

Japanese Internment World War II Reality vs. Propaganda

WWII Propaganda Study

World War 2 Propaganda Mini Lesson

World War II - Homefront Propaganda Gallery Walk

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

The Power of Propaganda in World War II

Published: august 29, 2018.

In a world before social media and the internet, how did the United States encourage and promote American citizens in the 1930s and 1940s to contribute to the war effort? The answer-propaganda and lots of it. While propaganda took many forms, perhaps its strongest and the most effective channel was Hollywood films. In this Thought Hub vlog, Rob Price, M.F.A., shares the impact of these films in America during this era and how many young filmmakers put their careers on hold to contribute to the war effort.

– [MUSIC PLAYING] I think I was about 10 years old the day that my grandfather showed me a piece of history, a secret he kept hidden for decades in a closet. It was a private piece of history from his years of service in the US Army. He had served as a medic, you see, and he would routinely be sent to the front lines of battle, just hours before his arrival. He would look over the troops and see what was happening there. And one day, he found something very interesting. There’s a picture of my grandfather with my boys and my father right there. So he comes to the area where there have been battles just hours before. And he’s tending to the US wounded, and he approached several dead German soldiers. And he noticed at least one of the bodies still had one of these. He picked it up, looked it over. He marveled at the German engineering of this now famous German Luger pistol. It caught his eye. So, being a Price, he just took it and kept it. Tucked it away in his back pocket, into the Jeep, and it made its way all the way back to his hometown of Muncie, Indiana. Well, that day, he showed me this pistol. I was like transported back in time to touch a piece of history that, today, I realize is very sacred to America. You see, my grandfather was a member of what many historians call the greatest generation. These were the young adult men and women of the 1940s, of whom it can be argued that they saved the world. They kept the ideals of freedom and democracy alive for you and I. World War II was the war, friends, that sent men like my grandfather and women like my grandmother to the factories across America, to the front lines overseas, to work the jobs that men left behind. And history informs us that almost every single American wanted to do something to contribute to the war. Men were willing to fight, women willing to work. War bonds were being purchased in mass quantities, and people were more than happy to even ration their own food. But the question I want to answer today is this– in a world way before the dawn of the internet and instant social media, how did all this happen? How did the United States get what seemed like every American citizen on board to contribute to the war effort? I submit to you the answer, as Dr. [? Loeb ?] referred to yesterday and Professor [INAUDIBLE] referred to today, was carefully crafted propaganda, a lot of it. What is propaganda? Well, it’s defined as information of a biased nature used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or a point of view. Now, in the case of World War II, there was propaganda everywhere, with phrases like the buy war bonds, and [INAUDIBLE] of course I can. You saw those. And my favorite– you buy them, we’ll fly them. It was in TV shows, commercials, on the radio. Even Donald Duck was leveraged in the propaganda machine. I mean, what kid back in the 1940s did not love one of Walt Disney’s favorite characters? But the war effort for propaganda was most prevalent through the influence of Hollywood. And many of these influencers were commissioned and paid for by something called the US War Department. A handful of promising young film directors put their careers on hold to join the war effort. These included men like- you need to know these names– Frank Capra, John Huston, George Stevens, William Wyler, John Ford. These men were all featured in the recent Netflix documentary series called Five Came Back. And I really encourage you to watch this three part series if you’re interested in further exploring their contributions to our nation. All of these men paid a very personal price for the war. Some returned to Tinseltown only to find that they had been penalized for being away from the machines of the Hollywood system. Others seemed unable to return to their producing more lighter comedic works. In fact, George Stevens, he was known for his humor before the war. Well, he turned his post-war attention to more somber and sober works like A Place in the Sun and the film called Shane. He once said, I came back and I tried, I tried, to make a comedy. I just couldn’t do it. 1959, Stevens directed The Diary of Anne Frank. You heard Ms. Montgomery mention that film earlier, or that book earlier, where he tried to find a glimmer of hope in a world torn apart by the ravages of war. The narrative films and documentaries these men and others like them produced were laced, friends, with overt propaganda themes. And they were aimed at influencing the American people in their view of the war. These themes were potent weapons that not only motivated the troops to fight and folks at home to pitch in, but it also spread hatred of the Nazis and the Japanese. The mainstream messaging consisted of three powerfully effective themes. One was the nature of the enemy. Number two was the need for men to fight overseas. And three was the need for women to work and sacrifice. So let’s examine them all and see how film shots fired served as the primary propaganda machine of World War II. Number one, the nature of the enemy. This was the most common theme used in many films and poster propaganda during World War II. Stereotypes of Nazis and Japanese were used to spread racism and hatred for the opposition. Characters in a film commonly used offensive language in reference to these adversaries. The goal was to make Americans hate the enemy so much that they would do anything to help the US defeat them. In fact, in popular movies, such as 30 Seconds Over Tokyo and Destination Tokyo and many others, the Japanese enemy overseas are referred to as Japs– you heard that earlier, as well, in our presentations– which quickly evolved into a derogatory term across the entire United States. Millions of Americans began to mimic what they heard in the movies and refer to all Japanese as Japs. And sometimes even as rats and monkeys, whether they were the enemy or simply an innocent Japanese American. Tragically, this led to the mistreatment of thousands of Japanese Americans. Many were held here– you see the picture– in what’s called internment camps for the duration of the war, because of fears that they were spies for the Japanese empire. But the Japanese were not the only enemy targeted in American propaganda films. The Nazis, the German Nazis, received their fair share of film shots fired against them. However, the goal of the propaganda aimed at the Nazis was different than the goal aimed at the Japanese, you see. Instead of spreading racism, blanket racism, against an entire nation, films about Nazis made them appear so brutal and controlling against their own citizens that Americans would feel compassion for the innocent Germans. For example, in the film by Walt Disney titled Education for Death– The Making of the Nazi, nearly every aspect of German civil life was depicted as under strict control by the Nazi party. Genealogical paperwork had to show the child was pure Aryan. Even a baby’s name had to be approved. The film also showed Nazis brainwashing children in schools by instructing them to believe that Germans were a superior race with no tolerance for weaklings or inherited diseases. Perhaps the most crucial propaganda theme, though, was the need for men to fight overseas. Without American men willing to risk their lives in battle, there would be absolutely no way the US and their allies could win the war and defeat the Axis powers. The government had to convince millions of men to leave their families and safety behind to fight in a bloody and dangerous conflict. And yes, there was a national lottery, but let’s face it, it’s a lot easier to win when the troops voluntarily decide to fight for their country. So to aid in this campaign, the US War Department had an idea. They began to tap on the shoulder of the aforementioned Frank Capra, who had already produced two Hollywood hits. You might recognize these films– It Happened One Night and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Under the direction of a name you’ll recognize, chief of staff George C. Marshall, he directed a unique seven-episode series titled Why We Fight, which was aimed at showing American men what they were fighting for and why it was an honor to defend the great nation of America. During their first meeting together, General Marshall told Capra’s mission, quote, “Now, Capra, I want to nail down with you a plan to make a series of documented, factual-information films, the first in our history that will explain to our boys in the Army. Why we’re fighting and the principles for which we’re fighting. You have an opportunity to contribute enormously to your country and the cause of freedom.” Well, after meeting with Marshall, Capra was shown a frightening propaganda film produced by the enemy, the Nazis, titled The Triumph of the Will. This film instantly opened Capra’s eyes to the immense challenge that lay ahead. Capra described the film as, quote, “the ominous prelude of Hitler’s Holocaust of hate.” He said, “Satan could not have devised a more blood-chilling super spectacle.” Capra admitted he was paralyzed to compete against the strong-handed propaganda for the Nazis. He said the film had fired no guns and dropped no bombs, but as a psychological weapon aimed at destroying the will to resist, it was just as lethal. Capra then slipped into what we might call the dark night of the soul. Quote, he said, “I sat alone and I pondered, how could I mount a counterattack against the triumph of the will and keep alive our will to resist this master race concept? I was alone. No studio, no equipment, no personnel.” As he began to calculate his cinematic response, Capra quoted scripture as inspiration. “I thought of the Bible,” he said. “There was one sentence in it that always gave me–” he called them goose pimples. “You shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.” And then an idea was born inside of him. He may have called it a hunch, but I think it may have been more divine inspiration. He suggested to Marshall this. He said, let the enemy prove to our soldiers the enormity of his cause but the justice of ours. Let’s use the enemy’s own films to expose their enslaving ends. He then convinced the general to, quote, “Let’s let our boys hear of the Nazis and the Japs shout their own claims of master race crud, and our fighting men will know why they’re in uniform.” And that, friends, is exactly what Frank Capra did. He secretly began to acquire film reels of Nazi propaganda and began putting them into his own releases. In addition, the Why We Fight films use techniques such as nostalgic analogies to remind people of the challenges America had faced before and how we’d overcome them because of brave men. The films discussed the selling of America at Plymouth Rock, way back to the beginning of our nation, and the building of our colonies. These films idolized how men of valor fought in the American Revolution to defend their sacred freedoms. And that it was now in the hands of their generation, the greatest generation, to do the same for America. Propaganda films were beginning to have a very deep, felt impact on recruitment and morale. Now, think about this. Without Capra’s propaganda and other filmmakers like him, millions of men may not have freely enlisted in the Army, which may have led to a mandatory draft with a much wider net. But maybe more low approval ratings for America’s entanglement in the war, which may have then led to eventual withdrawal and ultimately defeat. But thanks, in part, to film propaganda, that never happened. The third one, though, is the final reel of film propaganda was the need for women to work and sacrifice. This focused the lens on this aspect of Americana. These messages showed how they could help in the war effort by taking those tough-nosed, dirty jobs in factories and manufacturing plants. In one scene from the film 30 Seconds Over Tokyo, the wives of fighter pilots off at war are talking about their lives. And one of them indicates she’s going to get a job in a defense factory because, “I can’t imagine just sitting around in my house doing nothing.” The goal of this film was for life to imitate art and embolden women across America to use their energies on the home front as a direct support system for their men in the military. A film called Women in Defense– it’s a short film produced by the Office of Emergency Management. It was actually written by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and it was narrated by popular actress Katharine Hepburn. The film script included on-the-nose lines such as, “American women are alert to the dangers which threatened our democracy today. Every woman has an important place in the national defense program, in science, in industry, and in the home.” These films made women feel important and that their physical efforts could make a significant impact in winning the war. Something American women had yet to fully experience, you could say, in the Revolutionary War, in the Civil War, and in World War I. Without American women working in these converted factories and other important plants, the government knew the US would not be able to manufacture supplies and weapons needed in a timely fashion. It was an edge, we could say, that the US military leveraged through messages in these wartime movies. These women were also encouraged by the US War Department to ration food for their families and go without luxuries they once enjoyed. In order for the US to have the best chance of winning, their kitchens would have to sacrifice food like butter and cheese and meat and jams and fruit. And the same rules applied to restaurants. In the film Destination Tokyo, captain of a ship writes a letter to his wife explaining how his son will not be able to get a toy train for Christmas because, quote, “we are in a war.” He continues writing that his son will understand the sacrifice. It’s worth giving up one toy for one Christmas so the US can win the war. He ends the letter with a promise that next Christmas will be different. This film featured, of course, the famous Cary Grant. In short order, women in America became accustomed to rationing and no longer mind doing so, because they knew that it was helping with the war effort. It was a powerful collective mindset planted by propaganda films. So, in summary, whether you agree or you disagree with the use of propaganda, it’s hard to argue its effectiveness in World War II. It created, number one, hate for the enemy. It brought out bravery and courage in men. It empowered women to work in these factories and these plants, and it convinced people to ration their food and help our troops believe in the cause of the war. Its effectiveness, friends, was indisputable. And propaganda films have a very important place in American World War II history. The propaganda during the war aided in creating a groundswell of support for the war. In fact, data shows that from 1917 to 1973, three of the top four years of what’s called inductions into service were from the World War II era– 3.0 in 1942, 3.3 in 1943, and 1.6 million in 1944. Now, these figures represent the number of folks who freely entered, who signed up for service to the selective service system. And in the end, it was America and her allies that triumphed against both the Japanese and the Germans, thanks in part to the film shots fired by the powerful propaganda machine of World War II. Thank you. [APPLAUSE] [MUSIC PLAYING]

Want more ThoughtHub content? Join the 3000+ people who receive our newsletter.

Strength and Honor: Essential Team Values (Part 1)

Leadership from the Proverbs: The Wisdom of Humility

Leadership from the Proverbs: Fear of the Lord

Production or People: What Should Pastors Prioritize?

*ThoughtHub is provided by SAGU, a private Christian university offering more than 60 Christ-centered academic programs – associates, bachelor’s and master’s and doctorate degrees in liberal arts and bible and church ministries.

Online Exhibits

Powers of Persuasion

"I Want You"

by James Montgomery Flagg, 1940. National Archives, Army Recruiting Bureau

View in National Archives Catalog

Guns, tanks, and bombs were the principal weapons of World War II, but there were other, more subtle forms of warfare as well. Words, posters, and films waged a constant battle for the hearts and minds of the American citizenry just as surely as military weapons engaged the enemy. Persuading the American public became a wartime industry, almost as important as the manufacturing of bullets and planes. The Government launched an aggressive propaganda campaign with clearly articulated goals and strategies to galvanize public support, and it recruited some of the nation's foremost intellectuals, artists, and filmmakers to wage the war on that front. Posters are the focus of this online exhibit, based on a more extensive exhibit that was presented in the National Archives Building in Washington, DC, from May 1994 to February 1995. It explores the strategies of persuasion as evidenced in the form and content of World War II posters. Quotes from official manuals and public leaders articulate how the Government sought to rally public opinion in support of the war's aims; quotes from popular songs and sayings attest to the success of the campaign that helped to sustain the war effort throughout the world-shaking events of World War II.

Jump to Part 1 Galleries:

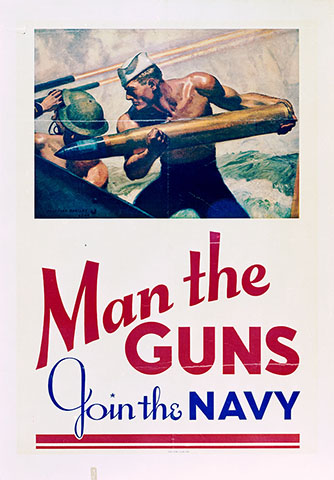

Man the Guns!

It's a Women's War Too!

United We Win

Use it up, wear it out, four freedoms.

Jump to Part 2 Galleries:

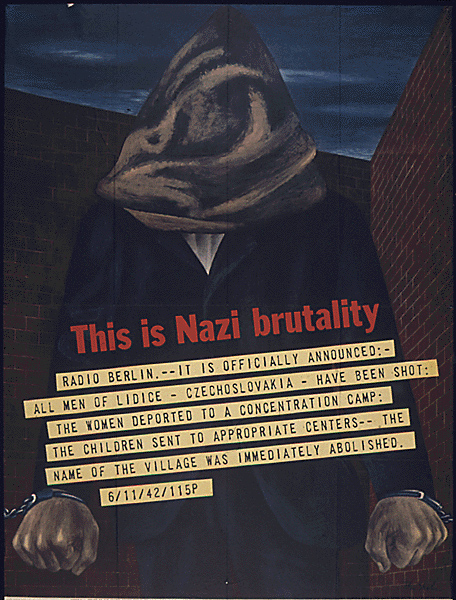

This is Nazi Brutality

He's watching you, meaning of sacrifice, stamp 'em out, part 1: patriotic pride.

View the Man the Guns! Gallery

Man the Guns—Join the Navy, by McClelland Barclay, 1942, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513519)

Keep 'em fighting. Production wins wars. Stop accidents, Printed for the National Safety Council, Inc., Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 514767)

Get hot—keep moving. Don't waste a precious minute., Records of War Production Board View in Online Gallery

(NAID: 535107)

Masculine strength was a common visual theme in patriotic posters. Pictures of powerful men and mighty machines illustrated America's ability to channel its formidable strength into the war effort. American muscle was presented in a proud display of national confidence.

Accentuate the Positive, Eliminate the Negative, Latch on to the Affirmative, Don't Mess with Mr. In-Between. 1945, Music by Harold Arlen, Lyrics by Johnny Mercer

It's a Woman's War Too!

View the It's a Woman's War Too! Gallery

Victory Waits On Your Fingers—Keep 'Em Flying Miss U.S.A., Produced by the Royal Typewriter Company for the U.S. Civil Service Commission, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 515979)

Longing Won't Bring Him Back Sooner...Get a War Job!, by Lawrence Wilbur, 1944, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513840)

We Can Do It!, by J. Howard Miller, Produced by Westinghouse for the War Production Co-Ordinating Committee, Records of the War Production Board View in Online Catalog

Of all the images of working women during World War II, the image of women in factories predominates. Rosie the Riveter—the strong, competent woman dressed in overalls and bandanna—was introduced as a symbol of patriotic womanhood. The accoutrements of war work—uniforms, tools, and lunch pails—were incorporated into the revised image of the feminine ideal.

(NAID: 535413)

In the face of acute wartime labor shortages, women were needed in the defense industries, the civilian service, and even the Armed Forces. Despite the continuing 20th century trend of women entering the workforce, publicity campaigns were aimed at those women who had never before held jobs. Poster and film images glorified and glamorized the roles of working women and suggested that a woman's femininity need not be sacrificed. Whether fulfilling their duty in the home, factory, office, or military, women were portrayed as attractive, confident, and resolved to do their part to win the war.

These jobs will have to be glorified as a patriotic war service if American women are to be persuaded to take them and stick to them. Their importance to a nation engaged in total war must be convincingly presented. Basic Program Plan for Womanpower Office of War Information

View the United We Win Gallery

United We Win, Photograph by Alexander Liberman, 1943, Printed by the Government, Printing Office for the War Manpower Commission, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513820)

Above and Beyondthe Call of Duty, by David Stone Martin, Printed by the Government, Printing Office for the Office of War Information, Records of the Office of War Information View in Online Catalog

At the beginning of the war, African Americans could join the Navy but could serve only as messmen. Doris ("Dorie") Miller joined the Navy and was in service on board the USS West Virginia during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Restricted to the position of messman, he received no gunnery training. But during the attack, at great personal risk, he manned the weapon of a fallen gunman and succeeded in hitting Japanese planes. He was awarded the Navy Cross, but only after persistent pressure from the black press.

(NAID: 535886)

Pvt. Joe Louis Says—We,re Going to do our part . . . and we'll win because we're on God's side, Records of the Office Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513548)

During World War II, racial restriction and segregation were facts of life in the U.S. military. Nevertheless, an overwhelming majority of African Americans participated wholeheartedly in the fight against the Axis powers. They did so, however, with an eye toward ending racial discrimination in American society. This objective was expressed in the call, initiated in the black press for the "Double V"—victory over fascism abroad and over racism at home. The Government was well aware of the demoralizing effects of racial prejudice on the American population and its impact on the war effort. Consequently, it promoted posters, pamphlets, and films highlighting the participation and achievement of African Americans in military and civilian life.

We say glibly that in the United States of America all men are free and equal, but do we treat them as if they were? . . . There is religious and racial prejudice everywhere in the land, and if there is a greater obstacle anywhere to the attainment of the teamwork we must have, no one knows what it is. Arthur Upham Pope, Chairman of the Committee for National Morale, in America Organizes to Win the War

View the Use It Up, Wear It Out Gallery

When You Ride Alone You ride with Hilter!, by Weimer Pursell, 1943, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 516143)

Save Waste Fats for Explosives, by Henry Koerner, 1943, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513832)

Waste Helps the Enemy, by Vanderlaan, Records of the War Production Board View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 533960)

During the war years, gasoline, rubber, sugar, butter, and meat were rationed. Government publicity reminded people that shortages of these materials occurred because they were going to the troops, and that civilians should take part in conservation and salvage campaigns.

Astronomical quantities of everything and to hell with civilian needs. Donald Nelson, Chairman of the War Production Board, describing the military view of the American wartime industry.

View the Four Freedoms Gallery

Ours...to fight for—Freedom From Want, by Norman Rockwell, ©1943 SEPS: The Curtis Publishing Co., Agent

Printed by the Government Printing Office for the Office of War Information, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513710)

Save Freedom of Speech, by Norman Rockwell, ©1943 SEPS: The Curtis Publishing Co., Agent, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the Office of War Information, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513711)

Save Freedom of Worship, by Norman Rockwell, ©1943 SEPS: The Curtis Publishing Co., Agent, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the Office of War Information, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513712)

Ours...to fight for—Freedom From Fear, by Norman Rockwell, ©1943 SEPS: The Curtis Publishing Co., Agent, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the Office of War Information, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513666)

President Roosevelt was a gifted communicator. On January 6, 1941, he addressed Congress, delivering the historic "Four Freedoms" speech. At a time when Western Europe lay under Nazi domination, Roosevelt presented a vision in which the American ideals of individual liberties were extended throughout the world. Alerting Congress and the nation to the necessity of war, Roosevelt articulated the ideological aims of the conflict. Eloquently, he appealed to Americans' most profound beliefs about freedom. The speech so inspired illustrator Norman Rockwell that he created a series of paintings on the "Four Freedoms" theme. In the series, he translated abstract concepts of freedom into four scenes of everyday American life. Although the Government initially rejected Rockwell's offer to create paintings on the "Four Freedoms" theme, the images were publicly circulated when The Saturday Evening Post, one of the nation's most popular magazines, commissioned and reproduced the paintings. After winning public approval, the paintings served as the centerpiece of a massive U.S. war bond drive and were put into service to help explain the war's aims.

We look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want . . . everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear . . . anywhere in the world. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message to Congress, January 6, 1941

Part 2: Staying Vigilant

View the Warning! Gallery

WARNING! Our Homes Are in Danger Now!, produced by the General Motors Corporation, 1942, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 516040)

Keep These Hands Off!, by G. K. Odell, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

A study of commercial posters undertaken by the U.S. Government found that images of women and children in danger were effective emotional devices. The Canadian poster at right was part of the study and served as a model for American posters, such as the one below, that adopted a similar visual theme.

(NAID: 513550)

Don't Let That Shadow Touch Them. Buy War Bonds., by Lawrence B. Smith, 1942, Produced for the Government Printing Office for the U.S. Treasury, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513572)

We're Fighting to Prevent This, by C. R. Miller, Think America Institute, Kelly Read & Co., Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 516102)

Public relations specialists advised the U.S. Government that the most effective war posters were the ones that appealed to the emotions. The posters shown here played on the public's fear of the enemy. The images depict Americans in imminent danger-their backs against the wall, living in the shadow of Axis domination.

Commercial advertising usually takes the positive note in normal times . . . But these are not normal times; this is not even a normal war; it's hell's ideal of human catastrophy [sic], so menace and fear motives are a definite part of publicity programs, including the visual. Statement on Current Information Objective Office of Facts and Figures

View the This is Nazi Brutality Gallery

This is Nazi Brutality, by Ben Shahn, 1942, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the Office of War Information, Records of the Office Government Reports View in Online Catalog

Lidice was a Czech mining village that was obliterated by the Nazis in retaliation for the 1942 shooting of a Nazi official by two Czechs. All men of the village were killed in a 10-hour massacre; the women and children were sent to concentration camps. The destruction of Lidice became a symbol for the brutality of Nazi occupation during World War II.

(NAID: 513687)

We French Workers Warn You...Defeat Means Slavery, Starvation and Death., By Ben Shahn, 1942, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the War Information Board, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513688)

The Sowers, by Thomas Hart Benton, 1942, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

Artist Thomas Hart Benton believed that it was the artist's role either to fight or to "bring the bloody actual realities of this war home to the American people." In a series of eight paintings, Benton portrayed the violence and barbarity of fascism. "The Sowers" shows the enemy as bulky, brutish monsters tossing human skulls onto the ground.

(NAID: 515648)

Many of the fear-inspiring posters depicted Nazi acts of atrocity. Although brutality is always part of war, the atrocities of World War II were so terrible, and of such magnitude, as to engender a new category of crime—crimes against humanity. The images here were composed to foster fear. Implicit in these posters is the idea that what happened there could happen here.

Under their system, the individual is a cog in a military machine, a cipher in an economic despotism; the individual is a slave. These facts are documented in the degradation and suffering of the conquered countries, whose fate is shared equally by the willing satellites and the misguided appeasers of the Axis. Government Information Manual for the Motion Picture Industry Office of War Information

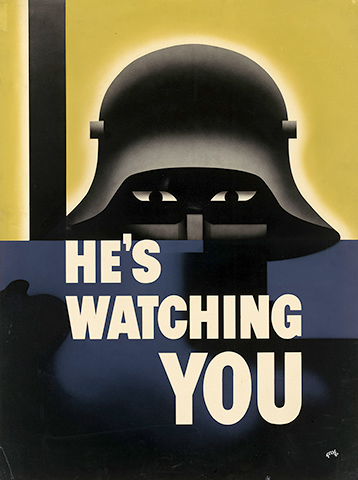

View the He's Watching You Gallery

He's Watching You, by Glenn Grohe, ca. 1942, Gouache on cardboard, Records of the Office of War Information View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 7387549)

Someone Talked!, by Siebel, 1942, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the Office of War Information, Records of the Office of War Information View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513672)

...Because Somebody Talked!, By Wesley, 1943, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the Office of War Information, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513669)

Wanted! For Murder, by Victor Keppler, 1944, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

A woman—someone who could resemble the viewer`s neighbor, sister, wife, or daughter—was shown on a "wanted" poster as an unwitting murderess.

At least one viewer voiced objection to the choice of a female model. A letter from a resident of Hawaii to the Office of War Information reads, in part, "American women who are knitting, rolling bandages, working long hours at war jobs and then carrying on with 'women's work' at home—in short, taking over the countless drab duties to which no salary and no glory are attached, resent these unwarranted and presumptuous accusations which have no basis in fact, but from the time-worn gags of newspaper funny men."

(NAID: 513599)

Concerns about national security intensify in wartime. During World War II, the Government alerted citizens to the presence of enemy spies and saboteurs lurking just below the surface of American society. "Careless talk" posters warned people that small snippets of information regarding troop movements or other logistical details would be useful to the enemy. Well-meaning citizens could easily compromise national security and soldiers' safety with careless talk.

Words are ammunition. Each word an American utters either helps or hurts the war effort. He must stop rumors. He must challenge the cynic and the appeaser. He must not speak recklessly. He must remember that the enemy is listening. Government Information Manual for the Motion Picture Industry Office of War Information

View the Meaning of Sacrifice Gallery

You Talk of Sacrifice..., Produced by Winchester, Records of the War Production Board View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 535236)

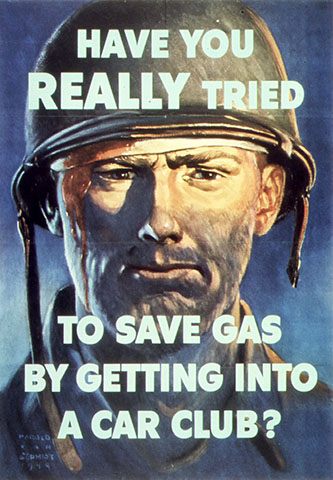

Have You Really Tried to Save Gas by Getting Into a Car Club?, By Harold Von Schmidt, 1944, Printed by the Government Printing Office, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 513630)

Miles of Hell to Tokyo!, By Amos Sewell, 1945, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the War Manpower Commission, Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 515009)

To guard against complacency, the Government promoted messages that reminded civilian America of the suffering and sacrifices that were being made by its Armed Forces overseas.

The mortal realities of war must be impressed vividly on every citizen. There is a lighter side to the war picture, particularly among Americans, who are irrepressibly cheerful and optimistic. But war means death. It means suffering and sorrow. The men in the service are given no illusions as to the grimness of the business in which they are engaged. We owe it to them to rid ourselves of any false notions we may have about the nature of war. Government Information Manual for the Motion Picture Industry Office of War Information

View the Stamp 'Em Out! Gallery

Stamp `Em Out!, Produced by RCA Manufacturing Company, Inc., Records of the Office of Government Reports View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 515473)

More Production, by Zudor, Printed by the Government Printing Office for the War Production Board, Records of the Office of War Information View in Online Catalog

(NAID: 7387556)

The Government tried to identify the most effective poster style. One government-commissioned study concluded that the best posters were those that made a direct, emotional appeal and presented realistic pictures in photographic detail. The study found that symbolic or humorous posters attracted less attention, made a less favorable impression, and did not inspire enthusiasm. Nevertheless, many symbolic and humorous posters were judged to be outstanding in national poster competitions during the war.

War posters that are symbolic do not attract a great deal of attention, and they fail to arouse enthusiasm. Often, they are misunderstood by those who see them. How to Make Posters That Will Help Win The War, Office of Facts and Figures, 1942

Additional Media

Song: "Any Bonds Today?"

Transcript:

"any bonds today bonds of freedom that's what i'm selling any bonds today scrape up the most you can here comes the freedom man asking you to buy a share of freedom today, any stamps today we'll be blest if we all invest in the u.s.a. here comes the freedom man can't make tomorrow's plan not unless you buy a share of freedom today".

Speech: President Roosevelt's Address

Transcript: Excerpt from President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Message to Congress on January 6, 1941

"the first is the freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world. the second is the freedom of every person to worship god in his own way—everywhere in the world. the third is freedom from want—which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world. the fourth is freedom from fear—which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world." (applause).

Video: Bugs Bunny

Video Description: Bugs Bunny enters stage right in front of a backdrop of Archibald McNeal Willard's painting, "Spirit of '76" showing three colonial soldiers with a fife, drum, and flag. Bugs wears a patriotic red and white striped top hat with a band of blue and white stars that he waves and tosses off stage left. Bugs sings "Any Bonds Today?", dances and throws blue papers printed with "Bonds" toward the audience. Elmer Fudd and Porky Pig, in Army and Navy uniforms, join Bugs onstage. The trio dances and sings in front of a backdrop showing a combat scene with ships and planes. As the song ends with a musical flourish, the cartoon fades to a gold background with a Minute Man on the left and the slogan "For Defense Buy United States Savings Bonds and Stamps."

History | July 11, 2022

How Disney Propaganda Shaped Life on the Home Front During WWII

A traveling exhibition traces how the animation studio mobilized to support the Allied war effort

:focal(1501x1186:1502x1187)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/32/79/32799d2f-8b63-4d4f-9744-7bffd427276c/disney_studio_artist_donald_duck_title_card_c_1942_collection_of_the_walt_disney_family_foundation_c_disney.jpg)

Marilyn Chase

When World War II rewrote the script for Americans’ daily lives, beloved cartoon characters were cast in new roles, too. Donald Duck (then Disney’s biggest star ) donned khakis as a United States Army recruit, while Minnie Mouse recycled leftover bacon grease to make explosives. Uncle Sam deployed the whole Disney crew, reassigning its members from pratfalls to pitching war bonds and victory gardens in animated movies.

The majority of the Walt Disney Company ’s military training films and educational shorts adopted an uplifting approach to patriotism. But others—in line with the fearful , racially charged wartime climate—stereotyped or demonized the enemy. Despite the fact that World War II saved the studio from financial ruin, Disney has long been reluctant to revisit its wartime history. (Though a spokesperson initially offered an interview with a Disney archivist, the company ultimately declined to comment.) Since its founding in 1923, the studio has meticulously guarded its family image both at home and abroad, including in Japan and Germany —countries that were once America’s enemies.

“It’s not a story the company tells,” says Kirsten Komoroske , executive director of the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco. The world of Disney is seen as “an upbeat place to take refuge,” she adds. “A feel-good place. War isn’t a popular topic.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9e/e6/9ee61f75-e171-4ab0-9193-de5db2761f0b/disney_studio_artist_remember_pearl_harbor_poster_1942_courtesy_of_the_walt_disney_archives_c_disney.jpg)

Nevertheless, this little-known chapter in entertainment history unfolds in a new exhibition, “ The Walt Disney Studios and World War II ,” on view through February at the Museum of Flight in Seattle. The traveling show, which debuted at the Walt Disney Family Museum last year, features 550 photos, drawings, prints and video clips that demonstrate how Disney artists turned their energies from fantasy fare to propaganda. Additional venues are still to be announced. (The San Francisco museum, established by Walt Disney’s late daughter Diane Disney Miller and her son Walter Miller, is a separate entity from the Walt Disney Company, but the two collaborated closely on the exhibition, with the entertainment conglomerate providing many of the artifacts on view.)

According to Komoroske, the show represents Disney’s “first exhibition on World War II.” Cash-strapped and ready to capitalize on the nation’s patriotic zeal, the studio turned its attention to propaganda, alternatively educating, entertaining and indoctrinating audiences.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor ushered in a singular era for both Disney and the U.S. at large. The Disney Studios lot in Burbank, California, was converted into a military base almost overnight. A phone call from Washington, D.C. ordered the company to make room for 500 personnel from an anti-aircraft unit. About 700 showed up, with vehicles, communications, camouflage and three million rounds of ammunition in tow. Disney also signed a $90,000 Navy contract, agreeing to make 20 training films on topics like how to spot enemy planes. The home of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs soon saw uniformed soldiers marching down the studio’s Dopey Drive; by 1943, upward of 90 percent of Disney’s work was related to the war effort.

Despite viewing himself as a patriot—he’d volunteered as a driver for the Red Cross ambulance corps during World War I—company co-founder Walt initially voiced misgivings about politicizing his product. As Wallace Deuel , a member of the wartime Coordinator’s Office, told a Treasury Department official, “Disney is fearful of being labeled as a propagandist in the public mind, with consequent damage to his reputation as a whimsical, non-political artist.” Still, the mogul—who expressed few overtly political views at this stage of his life, though he later became active in conservative Republican politics—made peace with orders to put his studio on a wartime footing, commenting in an audio clip played in the show that “it was kind of exciting.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a6/54/a654d3bb-c939-422d-913c-89f3a37f30ee/fasdfsa.jpg)

Pragmatic as well as patriotic motives fueled Walt’s eventual wartime zeal. Though popular today, Fantasia (1940), Pinocchio (1940) and Bambi (1942) all logged early box office losses upon their release. In Europe, the war had closed movie theaters, shrinking global markets. At home, Dumbo missed being named Time ’s 1941 “ Mammal of the Year ”—a play on the magazine’s “ Person of the Year ” franchise—after the Pearl Harbor attack bumped him off the cover in favor of General Douglas MacArthur . If war posed a business problem for Disney, then converting to wartime production was the solution.

To support the war effort, Disney designed emblems for the military, produced propaganda films and lent its iconic characters’ likenesses to different government agencies, among other activities. The studio provided training films and educational shorts at cost , with Walt saying, “I don’t like this profit during war … when people are out there giving up their lives.”

Free of charge, the company’s artists also created over 1,200 insignia for different military units, including the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) and the famed “ Flying Tigers .” Disney-designed “ nose art ” featuring characters like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck adorned aircraft fuselages.

“The insignia were extremely effective for Disney as a morale booster,” says Bethanee Bemis , a scholar at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History whose research focuses on Disney’s impact on American culture. “[They were] a reminder of home [that soldiers] got to carry into battle.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8b/93/8b932676-3838-4f7f-82d5-5432753368aa/1355-3-2.jpeg)

Disney also pitched in to raise funds for the war. In 1943, the company granted the Treasury Department permission to feature 22 characters, among them Donald Duck, Bambi and the seven dwarfs, on the borders of bond certificates made for children.

Though Disney only formally joined the cause after Pearl Harbor, executives had embraced defense-related projects before the attack, correctly sensing that military contracts could keep studio lights on and artists working. The pivot from whimsy to nuts and bolts was showcased in utilitarian titles like Four Methods of Flush Riveting , a 1942 mechanical training film made for Lockheed Martin.

As military personnel established operations in Burbank, Disney production surged tenfold from an average of 30,000 feet of film per year to 300,000. Some offerings catered directly to soldiers , covering such topics as Why We Fight and Tuning Transmitters . Others appealed to a broader audience: In the animated propaganda film Victory Through Air Power , for example, the company promoted the strategic advantages of long-range bombers. Disney taught science and civics lessons, too. The Grain That Built a Hemisphere —the first in a series of five films centered on agriculture—touted the importance of corn, while a radio in The New Spirit informed Donald Duck that real patriots pay timely “taxes to beat the Axis.

Mobilizing soldiers bound for combat and engaging civilians on the home front also led Disney to paint the enemy as immoral or even inhuman, most prominently in short films like Der Fuehrer’s Face , a 1943 cartoon starring Donald Duck; Commando Duck , which finds Donald facing down caricatured Japanese snipers in the Pacific; and Reason and Emotion , which argues that Hitler destroyed Germans’ reason by appealing to the emotions of fear, pride and hate.

“It’s the quickest way to play to people’s base emotions: the us-versus-them mentality,” says Bemis. “It’s an instinct that if you’re going to fight someone, you have to dehumanize them, because otherwise, how could you stand what you have to do?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/35/c0/35c09276-aafa-468b-928d-a4421df528e7/001-009portraiture.jpeg)

Der Fuehrer’s Face is a centerpiece of the exhibition and connects many of its messages. Stuck in a nightmare, Donald is forced to toil in a German arms factory and repeatedly salute fascist leaders. Creature comforts are few and far between: Awakened by a swastika-laden alarm clock, Donald sneaks a cup of coffee, gnaws on a rock-hard slice of bread, and savors a sniff of bacon-and-egg scented perfume. A marching band featuring Axis musicians with exaggerated facial features provides the backdrop to his disastrous day, chanting such lines as, “Heil, heil! Right in der Fuehrer’s face!”

Driven to exhaustion, the hapless duck hallucinates that the bombshells he’s assembling morph into snakes and musical instruments before finally waking up in his own bed. Clad in stars-and-stripes pajamas, Donald hugs his model Statue of Liberty and not-so-subtly summarizes the short’s overall message, declaring, “Am I glad to be a citizen of the United States of America.” The film—heavily influenced by Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) and The Great Dictator (1940), which satirized totalitarianism and tyrants—went on to win the 1943 Oscar for Best Short Subject (Cartoon). According to contemporary newspaper reports , the public lauded the short as “Walt Disney’s funniest creation,” a “morale-builder” and “one of those pictures in which everybody working on it took the greatest pleasure in their [contributions] to its production.”

To wartime white audiences, the animated short sold a patriotic message about the freedoms of American life—but it also epitomized the racist stereotyping of the time. Adolf Hitler appears as a shrieking buffoon. Benito Mussolini is a jowly thug, while Emperor Hirohito has yellow skin, buck teeth and slanted eyes. Historian Brian Niiya , editor of the online Densho Encyclopedia , which chronicles Japanese American experiences during World War II, explains why the Axis dictators are depicted in different styles.

“I was struck by the fact that the Hitler character looks somewhat realistic, while the Hirohito character doesn’t even look human,” Niiya says. “You see this in much of the imagery of [the] ‘Japanese’ in this time period, where they are sometimes even explicitly made into animals. Similarly, the white band members at least look human, while the ‘Japanese’ character ... barely does.”

He adds, “These types of portrayals contribute to the general sense that Japanese [people] were all the same and less than human.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/63/5b/635b3f4b-0460-43da-bada-ed9d01b45a2b/5063_-_1.jpeg)

As Bemis says, “If we were to see these short films on Disney+, [they] would come with a warning” akin to the online advisories cautioning viewers about politically incorrect content in classic Disney films like Peter Pan and The Aristocats .

Indeed, a similar notice appears at the exhibition’s entry:

Negative stereotypes of people and cultures, as well as other offensive imagery, were used as part of the United States’ propaganda efforts during World War II. We acknowledge its harmful impact and hope to encourage mindful discussion about misrepresentation and negative stereotypes, and use these lessons from the past to create a more inclusive future.

Disney wasn’t alone in its use of racist imagery : In his 1942 political cartoon “ Waiting for the Signal From Home ,” for instance, Dr. Seuss conjured up nonexistent sabotage plots, drawing Japanese Americans lining up to collect TNT for an attack on California. Fearmongering and distortion were key elements of propagandists’ toolkits.

An aspect of World War II left undiscussed in the exhibition is the Holocaust. However grimly the Nazis are portrayed, the slaughter of six million Jews is not referenced in either film or print materials produced by Disney during the conflict.