Compassion Fatigue

Secondary Trauma, Vicarious Trauma

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

People whose professions lead to prolonged exposure to other people's trauma can be vulnerable to compassion fatigue, also known as secondary or vicarious trauma; they can experience acute symptoms that put their physical and mental health at risk, making them wary of giving and caring.

- Feeling Another’s Pain

- Compassion Fatigue in the General Public

- Treating Compassion Fatigue

Empathy is a valuable trait for the military, first responders, humanitarian aid workers, health care professionals, therapists, advocates for victims of domestic abuse , moderators of offensive online content, and journalists on the front lines of war and disaster. But the more such individuals open themselves up to others' pain, the more likely they will come to share those victims' feelings of heartbreak and devastation. This sapped ability to cope with secondary trauma can lead to total exhaustion of one’s mental and physical state.

Those who regularly experience vicarious trauma often neglect their own self-care and inner life as they struggle with images and stories that can’t be forgotten. Symptoms of compassion fatigue can include exhaustion, disrupted sleep, anxiety , headaches, stomach upset, irritability, numbness, a decreased sense of purpose, emotional disconnection, self-contempt, and difficulties with personal relationships.

Compassion fatigue can affect the most dedicated workers —people who continue to help by working extra shifts or foregoing days off, neglecting their own self-care. This can result from exposure to a single case of trauma, or from years of accumulated “emotional residue."

Burnout is not the same as compassion fatigue. Feeling drained from everyday stressors like work and childrearing results in burnout. Compassion fatigue is the strain of feeling for another’s pain. However, the symptoms are often similar for burnout .

To be more effective, studies have shown, some workers in helping professions may benefit from what’s known as “psychic numbing”—the ability to dial down one’s empathetic instincts while on the job, freeing up cognitive resources to find solutions to the problems in front of them rather than becoming paralyzed by the scope of need they see.

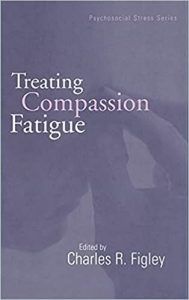

The understanding that exposure to the trauma of others could put people at risk has long been understood—historian Samuel Moyn has said, “Compassion fatigue is as old as compassion,” but the term was coined by historian Carla Joinson in 1992, and further defined and researched by psychologist Charles Figley, who describes it as “a state of exhaustion and dysfunction, biologically, physiologically and emotionally, as a result of prolonged exposure to compassion stress .”

A secondary definition of compassion fatigue refers to the experience of any empathetic individual who is acutely conscious of societal needs but feels helpless to solve them. People who actively engage in charity, or volunteering, may come to feel that they cannot commit any more energy, time, or money to the plight of others because they feel overwhelmed or paralyzed by pleas for support and that the world’s challenges are never-ending.

Evolutionary psychologists studying the development of human empathy suggest that we evolved to put our clan or family first and may struggle to extend our empathy to other groups. Some researchers even argue that empathy can fuel antisocial behavior such as aggression .

Research findings show that people tend to be more responsive to the needs of individuals rather than that of groups, or of the world as a whole. For this reason, charitable organizations have learned to focus their campaigns on how donors can help individual victims, not suffering groups.

Viewing violent news events on television or social media can also cause some people with high levels of empathy to experience symptoms similar to those of secondary trauma.

Soon after a catastrophe, an outpouring of assistance and support is extended to people affected by disaster. However, empathy starts to wear off quickly. This happens because we become fatigued when we are exposed continually to the suffering of others.

Hospitals, nursing and police unions, medical associations, correctional facilities , and other professional groups have become more aware of the effects of secondary trauma and now urge those in the helping professions to offset such fatigue.

We think someone else's problem is theirs, not ours. Yet we are all linked more than we realize. The more we bother to be a good influence in the world, the better the world will be—not just for others, but for us.

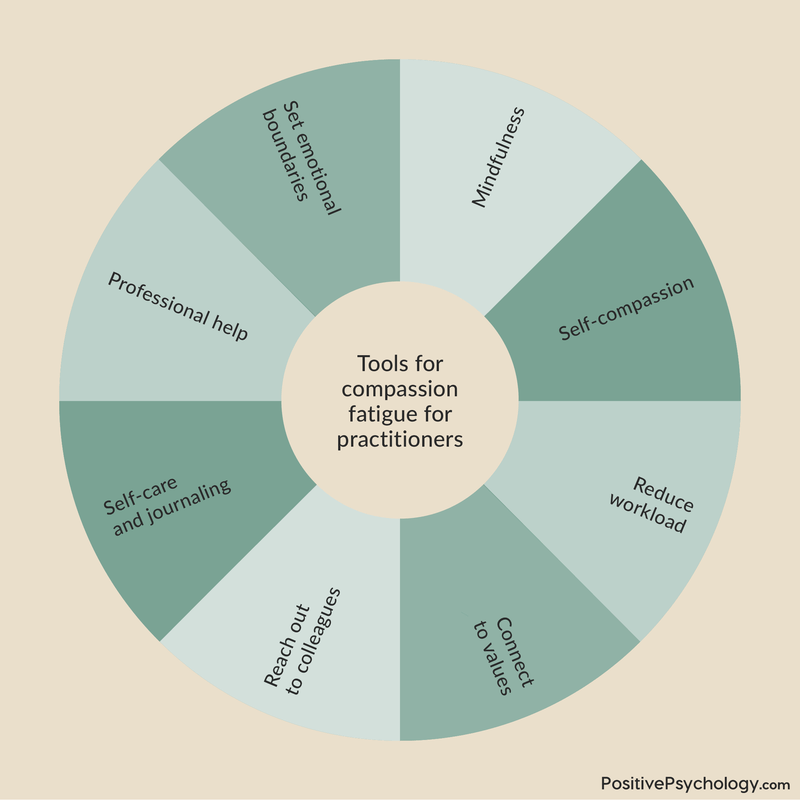

You can counteract such fatigue through regular exercise and healthy eating, a commitment to adequate rest and regular time off, and time in therapy . It also helps to set emotional boundaries without barricading yourself from the world.

People experiencing compassion fatigue may secretly self-medicate with alcohol , drugs, gambling, or food. Left unaddressed, compassion fatigue can develop into clinical depression or post- traumatic stress disorder.

Other techniques like mindfulness , meditation or yoga, and time with loved ones or in nature, or devoted to interests or hobbies outside of work have also been found to lessen the symptoms of compassion fatigue.

A 2015 study in the Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing argues for resilience training, a program designed to educate care workers about this type of fatigue and its risk factors. Such training teaches how to employ relaxation techniques and build social support networks to cope with symptoms that arise.

How exhaustion shapes identity, but we can reclaim agency over our lives. We can embrace renewal amidst fatigue.

Ancient wisdom offers a powerful lens for healthcare providers.

The "not good enough" mental narrative and the shameful feeling that comes with it are notable in people who have burnt out. Untamed, they can hinder one's recovery and growth.

What is the "payoff" waiting on the other side of grief and suffering? The most common response is resilience, but research shows it might be compassion.

January is often a time to reflect and set well-being intentions. For those already burnt out, this can be a daunting task. I hope these eight steps will set you up for success.

Burnout is a common problem. Individuals living with depression and anxiety may be at particularly high risk. Preventing burnout is easier than stopping it.

Learn 10 simple ways to charge your battery, avoid burnout, and remain connected to family, friends, colleagues, and patients during the holidays.

Psychotherapy is an incredibly meaningful profession. It draws on compassion and our values. Still, there are hazards of the job, including moral injury.

Seeing one's burnout through the lens of a blessing rather than shame is helpful toward recovery and growth. I share my burnout blessings in the hope it helps you to find yours.

Explore how evolving work cultures and historical contexts shape the current challenges in employee well-being and the multifaceted approach needed to combat burnout.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Empathy - Advanced Research and Applications

From Empathy to Compassion Fatigue: A Narrative Review of Implications in Healthcare

Submitted: 20 July 2022 Reviewed: 25 August 2022 Published: 18 October 2022

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.107399

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Empathy - Advanced Research and Applications

Edited by Sara Ventura

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

300 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Evidence is clear regarding the importance of empathy in the development of effective relationships between healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients in the delivery of successful healthcare. HCPs have pledged to relieve patient suffering, and they value the satisfaction felt from caring for their patients. However, empathy may lead to negative consequences for the empathiser. If there is a personal identification with the emotions of the distressed person, empathic concern may evolve into personal distress leading to compassion fatigue over time. A narrative review was used to explore the connection between empathy and compassion fatigue. A search of MEDLINE, PsychINFO and CINAHL resulted in 141 articles meeting the inclusion criteria. The results included in this chapter explore the practical implications of empathy in relation to compassion fatigue, examining the impact on HCPs as well as the potential risk factors and effective strategies to reduce compassion fatigue. The negative impact of compassion fatigue can have a severe impact on HCP well-being and can in turn impact the care received by the patient. Nevertheless, and despite existing effective strategies to support and manage those experiencing compassion fatigue, more needs to be done to prevent its development in HCPs.

- compassion fatigue

- healthcare profession

secondary traumatic stress

- vicarious trauma

Author Information

Jane graves.

- Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia

Caroline Joyce

Iman hegazi *.

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

1.1 empathy and compassion in the healthcare profession.

Compassion and respect for human dignity is enshrined in the codes of conduct for healthcare professionals (HCPs). Providing high-quality compassionate care is a fundamental aim of the helping professions and provides them with job satisfaction and a sense of value [ 1 ]. Being treated with compassion also has many patient benefits including increasing compliance with professional advice, improving satisfaction with services and enhancing health and quality of life [ 2 ]. Providing compassionate care requires kindness, empathy, and sensitivity [ 3 ].

Empathy refers to the capacity to understand and share the feelings of others such as pain, joy, fear, and other emotions [ 4 , 5 ]. Historically, emotional responses to patients were seen as threats to objectivity and doctors strived for detachment to be able to care, reliably, for all patients regardless of their personal feelings. Blumgart [ 6 ] recalls Sir William Osler’s “Aequanimitas” in his definition of ‘neutral empathy’ which states that a physician will do what needs to be done without feeling grief, regret, or other difficult emotions. Osler argues that by neutralising their emotions to the point that they feel nothing in response to patient suffering, physicians can ‘see into’ and, thereby, be able to ‘study’ the patient’s ‘inner life’ [ 7 ].

To avoid this conceived conflict between emotions and objectivity, ‘professional empathy’ was defined, on purely ‘cognitive’ basis, as “the act of correctly acknowledging the emotional state of another without experiencing that state oneself” [ 8 ]. This model of ‘detached concern’ assumes that knowing how the patient feels is no different from knowing that the patient is in a certain emotional state. However, the function of empathy is to recognise what it feels like to experience something, not merely to label emotional states [ 9 ]. Halpern [ 9 ] emphasises that patients sense when physicians are ‘emotionally attuned’ and that patients trust ‘emotionally attuned’ physicians and adhere better to their treatment.

In the clinical context, Stepien and Baernstein [ 10 ] combined the different definitions within the literature to put forward an expanded definition of empathy. This proposed definition includes four distinct dimensions: ‘ moral, emotive, cognitive, and behavioural’, all working in harmony to benefit the patient.

1.2 From empathy to compassion fatigue

Empathic perspective-taking is the level of empathy which most psychologists refer to when they speak of ‘empathy’. In this view, empathy is a cognitive state—dependent on imagination and mental attribution—combined with emotional engagement. A major manifestation of empathic perspective-taking is ‘targeted helping’ i.e., help and care based on a cognitive appreciation of the other’s specific need or situation [ 11 ]. The emotional component in providing care and support to people in distress can, over time, deplete the caregiver’s emotional resources engendering ‘compassion fatigue’; which is characterised by feelings of indifference to the suffering of others [ 12 ]. Joinson [ 13 ] in 1992 described compassion fatigue as a form of ‘occupational burnout’ experienced by those in the caring professions. Figley [ 14 ] then described compassion fatigue as ‘caregiver burnout’ and his 2002 model of compassion fatigue emphasised “the costs of caring, empathy, and emotional investment in helping the suffering” [ 15 ]. These ‘costs’ include the increased risk of mental and physical health problems in helping professionals [ 16 , 17 ]. Radey and Figley [ 12 ] suggest, “as our hearts go out to our clients through our sustained compassion, our hearts can give out from fatigue” (p. 207).

Compassion fatigue exists across a diverse range of healthcare professional groups, disciplines, and specialties [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Close to 7% of professionals who work with traumatised individuals exhibit emotional reactions that are similar to symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is not only seen in the healthcare sector, where it has been demonstrated in physicians, psychotherapists, and nurses—especially those working with critically ill children, in oncology and in trauma care [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]—but also, beyond the hospital setting in first responders, emergency teams, social workers, police officers, migration workers, and those working with the homeless [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ].

Levels of compassion fatigue have increased over the last decade [ 30 ]. More recently, compassion fatigue has become a significant concern during the COVID-19 crisis which has intensified the feelings of burnout, and compassion fatigue in healthcare workers, especially those working in specific COVID-19 units and in emergency departments, leaving no mental space for clinicians to experience authentic clinical empathy [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Recent pooled subscale scores indicate average to high levels compassion fatigue across a diverse healthcare practitioner groups [ 18 ]. For nurses, compassion fatigue rates are currently reported as just above 50% [ 35 ].

2. Aim of this chapter

The aim of this narrative review is to describe and synthesise the literature to explore the associations between empathy and compassion fatigue, and the impact of the latter in the healthcare profession. Also, to examine screening and management strategies of compassion fatigue in HCPs and deduce a conclusion from the evidence.

3. Methodology

We conducted a narrative review using the process described by Green et al. [ 36 ] to present objective conclusions based upon previously published literature that we have comprehensively reviewed. We opted for a narrative overview as narrative reviews can often serve to provoke thought and controversy and may be an excellent venue for presenting philosophical perspectives in a balanced manner [ 36 ].

3.1 Identifying relevant studies

We determined the search strategy through team discussions and pilot explorations of the different databases. We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), APA PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), and CINAHL Plus using the Boolean/Phrase (Empathy AND (‘Compassion Fatigue’ OR ‘Vicarious Trauma’) AND Health). We conducted the search during May and June of 2022 and included literature published between 2003 and 2022, including articles published online ahead of print. Initial search recovered 290 results from MEDLINE, 112 from CINAHL Plus, and 215 from PsycINFO.

3.2 Study selection

EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) was used to download the bibliographic details of studies yielded from the database searches and duplicates were deleted. Researchers screened article titles and abstracts to determine eligibility for full-text review based on relevance to the research topic. After this initial screening, all researchers read full texts of articles to determine eligibility for inclusion.

Inclusion criteria: The literature review included full text empirical research, which described empathy and compassion fatigue in healthcare workers, published in the English language in academic peer-reviewed journals over the last 20 years.

Exclusion criteria: Studies which covered other forms of vicarious trauma and post-traumatic stress, and studies which explored compassion fatigue in other professions, e.g., police officers, chaplaincy, caregivers, and migration agents, were excluded from this review.

Figure 1 shows a flowchart indicating the search and selection process. Following screening and full-text review, 92 articles were included in this literature review. Subsequent to the full text review, additional related references reported in the 92 examined articles were inspected, and those satisfying the inclusion criteria (n = 49) were also included in this literature review as secondary sources, leading to a total of 141 studies included in this review.

Flow diagram showing records identified from databases and the screening and selection process.

3.3 Collating, summarising, and reporting results

Authors read and objectively evaluated each of the 141 articles. They recorded how each article relates to the objectives of this narrative review. The authors are all HCPs, a chiropractor, psychologist, and a physician. This expertise in the area was useful in interpreting the literature but the authors were careful not to incorporate predispositions or biases by having multiple discussions throughout the review process.

The connection between empathy and compassion fatigue

The impact of compassion fatigue in healthcare

The detection and assessment of compassion fatigue

Management of compassion fatigue in healthcare professionals

HCPs are continually exposed to stressful events in their day-to-day work including frequent encounters with: (a) death and dying, (b) grieving families, (c) personal grief, (d) traumatic stories, (e) observing extreme physical pain in patients, (f) strong emotional states such as anger and depression, and (g) emotional and physical exhaustion [ 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Over time, high levels of stress can lead to burnout [ 39 , 40 ]. Burnout, a much-researched topic in the helping professions, has been defined as “a syndrome composed of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduction of personal accomplishments” [ 41 ]. Burnout may also lead to negative self-concept, negative attitudes about work, and a loss of caring about work-related issues [ 38 ].

Compassion fatigue, a construct similar to burnout, is a topic that has emerged in the literature in recent years [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Radley and Figley [ 12 ] define compassion as a “deep sense or quality of knowing or an awareness [among helping professionals] of the suffering of another coupled with the wish to relieve it” (p. 207). Compassion fatigue, a possible effect of long-term demonstrations of compassion, is defined as “a deep physical, emotional, and spiritual exhaustion accompanied by acute emotional pain” [ 45 ]. Compassion fatigue is thought to be a result of long exposure to the suffering of others, listening to descriptions of traumatic events experienced by others, little to no emotional support in the workplace, and poor self-care [ 12 ].

4.1 The connection between empathy and compassion fatigue

Compassion is an essential component of patient care provided by health professionals [ 46 ]. The care-giving relationship is founded on empathy and a critical characteristic of compassion fatigue is a loss or lack of empathy [ 47 , 48 ].

4.1.1 Temporary lapses in empathy

Temporary lapses in empathy are not uncommon in professional intervention and can have a variety of causes, ranging from experiences in the professional’s own life to reactions to clients’ situation [ 49 , 50 ]. Most clinicians experience them from time to time, and they rarely arouse major distress. There are reports of self-perceived lapses of empathy among emergency workers who provide services in the acute phase of the disaster and psychotherapists engaged in long-term psychotherapeutic relationships that started before and continued during and after the disaster. Many experience the conflict of ‘attention-to-self versus attention-to-client’ as temporary and normal for the situation. Reports by these professionals suggest that their lapses in availability and empathy cause them distress by impairing their self-esteem and fostering feelings of guilt, shame, and inadequacy [ 51 , 52 ].

Baum [ 53 ] suggests that the source of much of the widely reported distress among clinicians is an intra-psychic conflict between two conflicting psychological needs: the need to distance themselves from their clients and their need to raise their self-esteem, especially in experienced professionals whose anxiety is doubly intensified by their prior experiences. Much of the identity and self-esteem of helping professionals is anchored in their ability to be empathic, present, and containing towards those they help. The conflict from the fact that distancing helps the professionals to cope but reduces their ability to empathise with their clients, can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, and self-reproach.

Empathy is seen as comprising affective and cognitive components, whereas compassion is defined in terms of affective and behavioural elements. More specifically, compassion is perceived as comprising both of ‘feelings for’ the person who is suffering and a desire to act to relieve the suffering. The desire to act is distinct from the act itself [ 54 , 55 ].

Compassion fatigue involves a decline in one’s energy, desire, and/or ability to love, nurture, care for, or empathise with another’s suffering [ 56 , 57 , 58 ]. These critical defining attributes were used to develop a theoretical definition: “Compassion fatigue is the physical, emotional, and spiritual result of chronic self-sacrifice and/or prolonged exposure to difficult situations that renders a person unable to love, nurture, care for, or empathize with another’s suffering” [ 59 ].

4.1.2 Compassion fatigue and burnout

Compassion fatigue is strongly correlated with burnout [ 21 , 60 , 61 , 62 ]. Whilst stress and exhaustion are critical attributes of both concepts [ 21 , 60 ] the experience is of being in a ‘tired’ state in burnout and being in a ‘drained’ state in compassion fatigue [ 60 ] and thus devoid of ones resources [ 14 , 60 ].

Wynn [ 60 ] performed a comparative concept analysis examining the terms ‘burnout’ and ‘compassion fatigue’ using Walker and Avant methodology. The ability to recognise both concepts is pivotal in helping to establish strategies that support healthcare workers cope and achieve optimal occupational health. Wynn noted that burnout can be an antecedent of compassion fatigue. The important difference is that burnout as a precursor may be more readily responsive than compassion fatigue to restorative strategies such as time away from the work environment and behaviour modification [ 14 , 60 ]. If not addressed in its early stages compassion fatigue can permanently alter the compassionate ability of the individual [ 63 ]. Thus compassion fatigue may be considered to be a consequence of ongoing burnout in healthcare and indicate a further decline in the wellbeing of the healthcare professional.

The development of compassion fatigue is understood to be a cumulative and progressive process [ 64 ] Whist the development is cumulative, the onset of the experience compassion fatigue for the healthcare worker is a rapid one [ 35 , 65 ]. Comparatively burnout, a larger overarching construct, is experienced as a slowly progressing disorder and is associated with working in burdensome organisational environments [ 65 ]. Thus, in burnout conflict associated with the employer-employee relationship, and in compassion fatigue the conflict is primarily an internal one which is associated with the relationship between the healthcare professional and their patient [ 60 , 66 ].

4.1.3 Vicarious trauma and secondary traumatic stress

Meadors et al. [ 67 ] investigated the relationships between the terms associated with secondary traumatization using a correlational design. They established that there is a significant overlap between compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress (STS), and burnout, but that each of the concepts also had significant unexplained variance which suggests that there were differences between the concepts ( Table 1 ).

Definition of compassion fatigue and related terms.

Adapted from [ 67 ].

Secondary traumatization (ST) occurs as a natural consequence of caring between two people: one who has been traumatised and the other who is affected by the first’s traumatic experience [ 70 , 71 ]. Empathy and exposure are central in the development of ST [ 72 ] and can alter the way in which the healthcare worker experiences self, others, and the world [ 73 ].

The potential for ST begins with exposure to a client’s experience that is sufficient to evoke an arousal or emotional response [ 71 , 74 ]. Vulnerability to the client’s experience may be heightened by pre-existing conditions (risk factors) that produce greater sensitivity to the elements in the client’s situation leading to one’s absorption of the suffering itself [ 70 ]. The vicarious experiencing of the feelings, thoughts, or attitudes of another may result in the development of empathy, or the emotional connection that occurs through listening and bearing witness to graphic depictions of traumatic events. While bearing witness to the client’s suffering, the healthcare worker is susceptible to responses or reactions that may be physiological, behavioural, emotional, and/or cognitive in nature. Figley describes this as the “cost of caring” for those in emotional pain [ 71 ]. Alternate discussions such as those by Ledoux contest the notion of a ‘ cost to caring’ and propose that compassion fatigue occurs when ‘ care is obstructed’ [ 54 ].

Osland [ 75 ] reported that dietitians in high-risk workloads reported higher levels of STS than those with low-risk workloads, those in smaller facilities reported higher STS than larger facilities, and that working for >5 years as a dietitian was associated with higher rates of STS and burnout than in those working for <5 years. Those who perceived greater levels of support reported lower rates of burnout and higher rates of compassion satisfaction.

Zeidner et al. [ 47 ] examined the role of some personal and professional factors in compassion fatigue among health-care professionals. Research participants included 182 healthcare professionals who completed an assessment battery measuring compassion fatigue, emotion management, trait emotional intelligence, situation-specific coping strategies, and negative affect. Major findings indicate that self-reported traits ‘emotional intelligence’ and ‘ability-based emotion management’ are inversely associated with compassion fatigue; ‘adaptive coping’ is inversely related to compassion fatigue. Furthermore, problem-focused coping appeared to mediate the association between trait emotional intelligence and compassion fatigue. These findings highlighted the role of emotional factors in compassion fatigue among health-care professionals [ 47 ].

Rayner et al. [ 76 ] examined STS and related factors of empathetic behaviour and trauma caseload among 190 social workers and psychologists. Approximately 30 percent of participants met the criteria for a diagnosis of STS. Results indicated that there was a significant interaction between caseload trauma and personal trauma history on STS. Similarly, empathy alone was not directly related to changes in STS, yet the trauma in caseload effect on STS was moderated by empathy. A personal history of trauma was found to be related to increased levels of STS. However, contrary to expectation of prior research, empathy contributed to a reduction in STS, meaning that lower empathy levels were associated with a higher risk of developing STS.

Hubbard et al. [ 77 ] demonstrated consistency between the five key concepts of ST discussed in the literature, i.e., exposure, vulnerability, empathic engagement, reaction, and transformation. The analysis revealed a dynamic, fluid process in which the energy of the nurse, client, and environment were integrated and part of a diverse whole [ 78 ]. The dynamic nature of the nurses’ experiences created a “kaleidoscope of potentialities” [ 78 ], the outcome of which was either a positive or a negative trajectory. This revealed a new aspect of the dimension of alteration/transformation, which was the identification of a positive outcome during the ST process. These results suggest the importance of further research to assess the role and value of reflective supervision for HCPs and how this may enhance their personal and professional resilience.

4.2 Risk factors for compassion fatigue

Risk factors for the development of compassion fatigue include the intensity of the patient setting as healthcare professionals who care for traumatised individuals in critical care environments are at greater risk of acquiring compassion fatigue [ 20 ]. Engaging with the patients loved ones also places the healthcare professional at risk, particularly if the interactions involve conflict [ 20 ]. Other factors that place the professional at risk including undertaking difficult discussion with patients and families such as breaking bad or uncertain news to patients and their families. A lack of perceived managerial support compounds the risk [ 20 , 65 ] and working more hours perpetuates emotional exhaustion in providers [ 79 ].

Personal factors also appear to play a role in the risk of the development of compassion fatigue. Those who have less experience working as a healthcare professional are at greater risk [ 20 , 80 ] as are those with less maturity [ 80 ] or those who have not acquired a higher level of education or qualification in their profession [ 35 , 46 ].

Poor coping strategies and difficulty with emotional regulation also place providers at greater risk. These include being unable to process feelings in relation to trauma and caring for those who are impacted by suffering [ 20 , 47 ]. Being unable to identify effective coping mechanisms, adapt, manage emotion and develop one’s emotional intelligence [ 20 , 47 ]

There is some indication that one’s personality may also play a role and people with high sensitivity may be more vulnerable to compassion fatigue. People with an increased ability to perceive others feelings may have stronger emotional and physiological reactivity [ 81 ] and thus be more prone to compassion fatigue [ 82 ]. This may be compounded by the contract between the quality of care the healthcare professional may want to provide with what they are actually able to achieve [ 80 ].

Negative life events and pre-existing mental illnesses such as anxiety or depression have been found to increases a person’s susceptibility for compassion fatigue [ 18 ]. Similarly coexisting physical and emotional stress increases levels of existing compassion fatigue [ 80 ].

Certain workplace conditions and events are more likely to trigger the onset of compassion fatigue [ 60 ]. These include continuous and intense contact with patients, exposure to high levels of stress, exposure to suffering and work which requires a high use of self [ 83 ].

4.3 The impact of compassion fatigue

Compassion fatigue negatively impacts the healthcare professional, the patient, the organisation, and the healthcare system [ 19 ].

4.3.1 Impact on the healthcare professional

In order to support patient autonomy healthcare providers practice patient centred care. This care requires genuine engagement and an empathetic approach making exposure to patient trauma and suffering unavoidable for the health care professional [ 79 ].

4.3.1.1 Signs of compassion fatigue

Indicators of compassion fatigue frequently cited in the literature include exhaustion [ 14 , 60 ], reduced capacity for self-care [ 13 , 60 ], ineffective coping, poor judgement [ 83 ], inability to function [ 63 , 83 ], loss of empathy [ 60 , 83 ] and depersonalisation of patients [ 83 ].

4.3.1.1.1 Exhaustion

The experience of the depth of exhaustion has a number of descriptors in the literature. These include a include feelings of weariness [ 63 , 64 ] emptiness, of being drained [ 14 , 60 ] and a ‘profound fatigue of mind and body’ [ 80 ]. People with compassion fatigue feel completely depleted of one’s “biological, psychological, and social resources” [ 14 ] such that they have nothing more to give [ 14 , 60 ]. The individual wants to rest although concerningly rest does not result in increased energy levels or a sense of rejuvenation [ 14 , 60 ]. Individuals may try various attempts to replenish and yet the feeling of exhaustion remains [ 14 , 60 ].

4.3.1.1.2 Reduced capacity for self-care

In 1992 Joinson described compassion fatigue as the reduced capacity to self-care as a result of the sustained fatigue acquired by caring for others [ 13 ]. Recent synthesised descriptions of the experience of compassion fatigue include being left so physically and mentally exhausted and drained by patient care that the provider lacks empathy and is unable to cope [ 60 ].

4.3.1.1.3 Ineffective coping

Ineffective coping is a critical indicator of the occurrence of compassion fatigue [ 13 , 60 ]. When healthcare professionals are no longer able to recover from a depleted state despite using coping strategies the result is ineffective coping [ 60 ]. Coping strategies that may have worked successfully in the past become no longer effective [ 60 ]. Recovery from the stress and exhaustion of providing patient care [ 60 ], is no longer possible. Emotional responses may include feeling emotionally overwhelmed [ 63 , 84 , 85 ] and potentially experiencing an emotional breakdown [ 15 , 20 , 63 ].

4.3.1.1.4 Inability to function

Inability to function may be experienced as a diminished ability [ 15 ] or reduced endurance and output [ 63 , 83 ], leading to a diminished or ineffective work performance [ 13 , 63 , 83 ]. The experience of trauma-based symptoms, in addition to significant exhaustion results in a deterioration of function [ 63 ]. The compassionate energy required to care for patients has been consumed over time is distinguished beyond the point of possible replenishment. An inability to compassionately care for patients moves beyond the work environment and leads to an inability to function which impacts all aspects of the professionals life [ 63 ].

4.3.1.1.5 Loss of empathy

Whilst attempting to employ coping strategies to manage the stress of caregiving a loss of empathy occurs. In response to the relentless overwhelming stress and resultant exhaustion of care-giving a deep psychological shift occurs [ 60 , 86 ]. Health professionals lose their sensitivity to and understanding of the patient’s needs. The professional is no longer able to comprehend the patient’s perspectives or recognise their thoughts and feelings [ 60 , 86 ]. Thus patient experiences are no longer relatable and the health professional experiences compassion fatigue [ 60 , 86 ]. Factors that inhibit sustained energy and perpetuate compassion fatigue include time constraints, burnout [ 87 ] and caring for high-stakes patients [ 60 ]. Health professionals with their own personal history of trauma are also at greater risk of acquiring compassion fatigue [ 88 ] due to their sensitivity to secondary traumatic stress [ 76 ]. As a consequence of their empathy loss, the healthcare professional appears indifferent [ 14 , 15 ], unresponsive [ 63 ], callous [ 15 , 84 , 89 ] and unable to share in or alleviate the patients suffering [ 15 ].

4.3.1.1.6 Depersonalisation

Depersonalisation is a sense of detachment from oneself in which individuals perform tasks in a robotic fashion without emotion. It presents as a coping mechanism used to manage exhaustion [ 90 ] and to avoid the feelings of distress that may arise when a person is experiencing compassion fatigue. Whilst the response does not arise from a lack of empathy for the patient [ 60 ] the depersonalisation coping mechanism once triggered in the professional results in a lack human feelings or emotions in the work place. Consequently, this translates to a lack of human feelings in how the professional provides care, which results in substandard care [ 83 ]. The serious implications of depersonalisation in healthcare professionals arises when the lack of emotion in self, results in the professional viewing the patient as also inert or an ‘object’ and approaches the patient with an attitude of indifference [ 90 ].

Depersonalisation is a maladaptive coping mechanism seen in both burnout and compassion fatigue and occurs when individuals detach from their feelings and emotions in order to be able to function and complete work-related tasks [ 60 ]. Yet the severity of depersonalisation experienced in compassion fatigue leads the provider to view the patient as an ‘object’ [ 90 ] and the provider is no longer able to respond to the humanity within the patient. This emotionally dissociated approach sharply contrasts with anticipated patient expectations.

4.3.1.2 Symptoms of compassion fatigue

Compassion fatigue is a significant risk factor for well-being [ 20 , 25 ]. Compassion fatigue impacts ones physical and mental health [ 63 , 64 ] and leading to an array of potentiation indicators including psychological, physical, spiritual, and social symptoms [ 86 ]. As the condition progresses the professional experiences an increase in the scope and severity of symptoms [ 63 ]. For example the individual may experience physical symptoms of burnout, reduced work performance and physical complaints, the intellectual effects of impaired concentration, emotional effects of breakdown, the social symptoms of indifference towards patients and desire to quit, the spiritual effects of disinterest in introspection and dysfunctional coping behaviours [ 63 ].

4.3.1.2.1 Physical symptoms

Physical symptoms may include health complaints, intellectual effects and fatigue [ 15 , 63 ]. Health complaints may include gastrointestinal conditions and stomach pain, and headaches, including migraine [ 20 , 83 , 91 ]. Sleep disturbance is frequently cited [ 20 , 65 , 91 , 92 ] and people may be at greater risk of accidents [ 15 , 83 ]. Intellectual effects include impaired ability to concentrate [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 63 ], poor judgement [ 20 ] and disorganisation [ 63 , 89 ]. Fatigue may manifest as weariness [ 63 , 85 ] lack of energy [ 13 , 15 , 63 , 85 , 89 ] loss of strength [ 63 , 85 ] loss of endurance [ 63 , 85 ] and power of physical recovery [ 63 ] Complications of fatigue include weight gain or weight loss [ 83 ].

4.3.1.2.2 Psychological impact

The psychological impact of compassion fatigue is well established in the literature and manifests as stress, burnout [ 13 ], intrusive and pervasive thoughts [ 65 , 91 ] anxiety [ 13 , 63 , 64 ], and depression [ 13 , 20 , 60 , 63 , 64 , 65 ]. Compassion fatigue has been found to have a moderate correlation with anxiety and depression [ 93 ].

4.3.1.2.3 Emotional impact

The emotional impact of a loss of compassion is typically one of devastation for those in healthcare professions [ 13 ]. Compassion for others drives workplace motivation to serve and alleviate suffering [ 54 ]. People in nurturing roles are rewarded for putting others needs ahead of their own [ 13 ], and ethically a drive to nurture others connects with the ideal archetype of those in caring professions and a societal sense of social justice [ 54 ].

Emotional exhaustion and its consequential impact on one’s personal life are the most frequently reported emotional effects of compassion fatigue [ 20 , 94 ]. A person’s capacity to communicate with others is impaired and this extended into personal relationships. Individuals feel emotionally distressed or bereft and may well experience an emotional breakdown [ 15 , 60 , 63 , 65 , 80 , 83 ].

Indicators of compassion fatigue may include fluctuations in emotional states [ 91 , 92 ] or mood swings [ 20 ]. Impacted healthcare professionals may feel emotionally overwhelmed [ 63 , 84 , 85 ], irritable [ 14 , 20 , 63 , 64 ] angry, fearful, out of control [ 13 ]. or apathetic [ 13 , 63 , 84 ]. Ones outlook is likely to become negative [ 60 ] and people experience ‘work related dreads’. [ 91 ] Healthcare professionals are no longer able to feel empathy for those in their care or respond compassionately. They have an inability to share in, or alleviate suffering [ 15 ] and may respond with indifference [ 14 , 15 ], callousness [ 15 , 84 , 89 ] or be unresponsiveness [ 63 ] to patients at times when they previously would have been empathetic.

Spiritual effects include a lack of spiritual awareness and disinterest in introspection [ 15 , 63 , 85 ] which has the potential to result in poor judgement [ 15 , 63 ] cynical humour and dysfunctional coping behaviours such an increased consumption of alcohol, unhealthy food or pornography [ 91 ]. The impact is a loss of self-worth [ 95 ] which may be compounded by weight gain or loss [ 83 ] and its emotional impact.

4.3.2 The impact of compassion fatigue on patients

Patient care is negatively impacted by compassion fatigue and this impact is recognisable to patients. Health professionals effected by compassion fatigue experience a decreased ability to feel empathy and hence lack meaning in their work [ 20 , 96 ]. which results in substandard care [ 20 , 83 , 96 ]. The stress of the working environment is palpable to patients and is identifiable as a consequence of poor-quality care [ 60 , 97 ]. Patients depend on health professionals to alleviate the stress, anxiety and fear associated with their illness [ 90 ]. When patients sense the impact of compassion fatigue they question the quality and appropriateness of care which in turn escalates patient stress [ 60 ].

The relationship between the healthcare professional and the patient becomes compromised. The trauma response associated with compassion fatigue results in reduced or decreased workplace engagement [ 21 ] and avoidance of particular situations or patients [ 96 ]. The ultimate consequence of compassion fatigue and burnout is poor patient outcomes [ 60 ]. Indeed significant concerns arise regarding the potential for increased medical errors and patient safety [ 21 , 64 , 83 ].

4.3.3 The impact of compassion fatigue on organisations and the healthcare system

Staff who are experiencing compassion fatigue have reduced job satisfaction [ 21 ] and reduced efficiency levels resulting in reduced service quality [ 98 ]. Patient satisfaction levels are lower in institutions where job satisfaction and burnout levels are reduced [ 97 ]. Poor patient satisfaction levels result in reduced patient recommendation rates of same facility to family and friends [ 60 , 97 ].

Relationships with co-workers become negatively impacted [ 20 , 96 ] when a person is impacted by compassion fatigue. If working with colleagues who are equally exhausted and apathic [ 13 ] productivity and workplace morale decline [ 95 ]. The result is a poor work environment with lower levels of productivity, patient satisfaction and patient care outcomes [ 21 ]. Compassion fatigue is triggered by the ongoing use of empathy while caring for those who are suffering and the effect of a poor work environment [ 18 , 99 ]. Thus, the cycle of compassion fatigue perpetuates.

As staff fatigue, the rates of sick leave increase [ 83 ]. More staff members experience an intensifying desire to leave their workplace, profession [ 15 , 24 , 60 ] and specialty [ 80 ]. Compassion fatigue and burnout result in workplace imbalances [ 24 , 60 ] with higher rates of staff turnover [ 95 ], and attrition and eventually, workforce dropout [ 98 ]. Staff turnover rates are particularly volatile in in high-stakes environments [ 100 ] such as oncology and emergency medicine. Staff seek alternate employment opportunities in an attempt to combat excessive workplace stress. As turnover rates increase, the stress in the workplace intensifies as remaining staff attempt to continue short staffed [ 60 ].

Compounding the impact of compassion fatigue is the perception that indicators of a poor working environment, such as increased rates of absenteeism, reduced service quality, low levels of efficiency are being ignored by the organisation and healthcare system [ 18 , 98 ]. Concerns include the conclusion by staff that administrators do not consider caregiver stress when allocating tasks [ 13 ]. The impact of compassion fatigue is intensified when management fail to provide workplace acknowledgement, fail to provide opportunities for peer support and appear not to value work-life balance [ 80 ]. When the workplace culture is not addressed with opportunity for employee training, and a shift towards a compassionate organisational culture [ 65 ] staff in healthcare will continue to experience moderate to high levels of compassion fatigue.

As a consequence of the negative impact on productivity, job satisfaction and staff turnover, compassion fatigue also impedes workplace focus on patient safety [ 21 ] and thus has the potential to lead to an increase in medical errors and diminished patient outcomes [ 21 ]. Healthcare professionals experiencing burnout and compassion fatigue are more prone to medical error [ 83 ] as a result of compassion fatigue symptoms including exhaustion [ 14 , 60 ] and a diminished work performance [ 13 , 63 , 83 ].

In addition to the potential harm to patients and families, compassion fatigue related medical error has the potential to result in legal, reputational and economic loss, for individual healthcare providers [ 101 ]. The economic impact of an institution impacted by compassion fatigue staff turnover, patient dissatisfaction and concerns regarding medical error and patient safety is institutional financial loss [ 64 , 102 , 103 , 104 ]. Compassion is valued by patients and healthcare professionals alike and both patients and professionals raise concerns regarding a widespread and escalating lack of compassion in healthcare systems [ 30 , 101 ].

4.4 Detection and assessment of compassion fatigue

Compassion fatigue is commonly measured using the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) [ 105 , 106 ]. The self-score scale is a freely available to measure the negative and positive effects of caring and helping others who have experiences significant trauma or suffering.

The Compassion Fatigue Self-Test (CFST) was originally developed to measure compassion fatigue [ 107 ]. The CFST measures the level of risk of an individual to developing compassion fatigue. The scale included 40 items, divided into two subscales, compassion fatigue and job burnout; 23 items measure compassion fatigue and 17 items burnout. Using a five-point scale, respondents are asked to indicate how frequently a situation or particular characteristic is true of themselves (1 = rarely/never, 2 = at times, 3 = not sure, 4 = often, 5 = very often). On the subscale compassion fatigue, scores of 26 or below, indicate being at an extremely low risk, a score between 27 and 30, low risk, between 31 and 35 moderate risk, scores between 36 and 40 high risk and scores between 41 and above, indicate an extreme high risk of compassion fatigue. Scores on the subscale for burnout below 36 indicated an extremely low risk, between 37 and 50 moderate risk, 51–75 indicates high risk, and scores between 76 and 85 indicated an extremely high risk of burnout. The reported internal consistency alphas are reported to be between .86 to .94 [ 108 ]. The scale has been widely used in a variety of settings and has adequate reliability and validity [ 69 ]. The measure was specifically developed to measure both direct and indirect trauma making it a widely applied measure [ 108 ].

The CFST scale was revised and re-developed [ 106 ] into the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL). The revised scale included an additional subscale to measure compassion satisfaction. The three subscales total 30 items, using a six-point scale (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = a few times, 3 = somewhat, 4 = often, 5 = very often). Respondents are asked about their thoughts, feelings and behaviour at work. The first of the three sub-scales measures compassion satisfaction, a higher score on this scale represents a greater satisfaction as a caregiver and helping others. The second subscale, measures burnout and feelings of hopelessness at not being able to do a good job, and the third subscale measures compassion fatigue/secondary traumatic stress. A higher score on this subscale represents high levels of compassion fatigue/secondary traumatic stress. Each subscale includes 10 items, and the subscale scores cannot be combined to calculate a total score. The ProQOL scale improved on the psychometric properties of the CFST scale [ 105 , 106 ]. The scale with the additional subscale measuring compassion satisfaction incorporates the more positive and psychologically protective aspect of caring, capturing the rewarding and gratifying aspects of caring [ 105 , 106 ]. The Cronbach’s α values reported by Stamm for these scales were .82 for compassion satisfaction, .71 for burnout, and .78 for compassion fatigue [ 105 ]. The ProQOL is free to use and is readily available, as are guidelines for interpreting the results from the scale.

4.5 Management of compassion fatigue in healthcare professionals

Figley [ 70 ] believed to manage compassion fatigue in health professional a multifaceted approach is required that includes prevention, assessment and minimising the consequences. The impacts of compassion fatigue are far reaching for both the individual health professional and organisations. Helping protect healthcare professionals from developing compassion fatigue and managing those experiencing high levels of job burnout and secondary traumatic stress can be done through self-care, evidence-based interventions and creating organisations that are better able to support and protect their workers. By protecting health professionals ensures high quality patient care. Over the past few decades’ interventions have been developed to help reduce symptoms of compassion fatigue. Self-care techniques that can be used to help reduce the risk of developing compassion fatigues and managing the risks of providing compassionate care to patients and clients have been developed and promoted among health care professionals. Organisations also play a role in helping reduce the risk to their workers through better training, ongoing support and creating a support environment that recognises the risks to their staff.

4.5.1 Interventions for compassion fatigue

Interventions have been developed to both prevent and manage compassion fatigue in healthcare professionals. The strategies have included education interventions and developing skills such as resilience [ 109 ]. The Accelerated Recovery Program (ARP) is a program developed to reduce compassion fatigue, including secondary traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare professionals. The ARP was originally developed in 1997 [ 110 ], based on Figley’s work on compassion fatigue (1995). The main aim of the program is to build resilience skills to prevent compassion fatigue. The program duration is 5 weeks, consisting of a weekly 90–120-minute training sessions. A full assessment is undertaken in the first session, along with a discussion exploring the symptoms participants are experiencing. In the second session treatment goals and a timeline is discussed using self-visualisation techniques. The third session focuses on reframing and reprocessing the trauma experienced using eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing therapy and reviewing self-regulation strategies for managing situations. The fourth session incorporates video-dialogue techniques to enable the individuals to supervise themselves through the development of externalisation techniques. In the final session, closure and aftercare are addressed with the use of Pathways to recovery that include skill acquisition; self-care; connection with others; and internal conflict resolution. The program works by developing a person’s self-awareness of compassion fatigue and practicing regular self-care activities [ 110 ]. The ARP primarily focused on mental health and trauma workers [ 110 ] but its potential to be effective in reducing compassion fatigue among nurses and other healthcare profession is growing [ 24 ]. Evidence supports the use of the ARP to reduce compassion fatigue among health care professionals [ 24 , 111 , 112 ]. An adaptation of the ARP that reduced the training into a single four-hour session reported a similar significant reduction in compassion fatigue [ 113 ].

The Compassion Fatigue Resiliency program (CFRP) was based on the concepts of the ACP [ 110 ]. The program is a five-week formalised program to educate participants about compassion fatigue, the factors that contribute to it and the effects of chronic stress. The program interventions aim to reduce the effects of compassion fatigue with participants taking part in small group activities that allow them to build resilience through self-regulation, intentionality, self-validation, connection and self-care.

Evidence supports the effectiveness of the CRRP to reduce secondary traumatic stress by providing nurses with the ability to manage intrusive thoughts [ 24 ]. The program aids greater relaxation enabling individuals to better manage perceive threats, enabling them to manage chronic stress through self-regulation [ 114 ]. The benefits of the CFRP have been reported for healthcare providers in reducing the symptoms of compassion fatigue [ 115 , 116 , 117 ].

To improve the resilience of military healthcare professionals and reduce compassion fatigue the Army’s Care Provider Support Program (CPSP) was developed. During one-hour sessions, healthcare providers are educated to be able to assess themselves for compassion fatigue and identify when they need to take action. The program activities focus on developing self-awareness through group discussion and interactive participation, along with providing education on stress and resilience. Support for the intervention significantly reducing burnout was demonstrated by Weidleich et al. [ 118 ]. However, although a decrease in secondary trauma was reported this was not significant [ 118 ].

Overall, the usefulness of formal intervention programs developed to target reducing compassion fatigue have been reported in a number of healthcare professionals. Although, there is only limited evidence to support the effectiveness of the CPSP. Despite the evidence to support the use of these intervention programs provided in this section, due to the nature of health care settings it is not always practical or cost effective to run these programs for staff. Staff would be expected to attend these programs in their own time and the financial impact to organisations with other competing costs make these types of interventions unfeasible.

4.5.2 Self-care

Organisational resources may not be available or sufficient to address compassion fatigue in employees, therefore promoting self-care can be an effective way to support staff. Self-care interventions are commonly prescribed for health professions experiencing compassion fatigue. Successfully managing compassion fatigue can be done by developing strategies that enhance awareness and provide thoughtful self-care [ 119 ]. There are numerous self-care strategies that can be adopted and utilised by healthcare professionals.

Strategies and techniques that can be used to reduce the risk of compassion fatigue involve looking after general wellbeing, including diet, exercise and sleep. Evidence supports maintaining a healthy diet and getting the recommended amount of physical exercise help regulates mood [ 120 ] and reduce the risk of compassion fatigue [ 121 ]. Regular sleep also plays an important role in regulating mood. Sleep deprivation is associated with decrease cognitive performance and increases the risk of low mood such as anxiety and anger [ 122 ].

Nurturing the self can be done using a number of different techniques. Developing and practicing self-compassion can increase a person psychological wellbeing and assist professionals to better respond to the difficulties experienced in their jobs [ 123 , 124 ]. Self-care interventions developed aim to help healthcare professionals achieve work-life balance by developing coping skills to maintain both emotional and physical health [ 125 ], along with maintaining healthy social networks and participating in activities to promote relaxation such as meditation and mindfulness [ 126 , 127 ]. Other self-care activities that can be adopted to help to support emotional wellbeing involve creative writing [ 128 ]. Strategies have included the use of writing poems to explore difficulties with emotional connection [ 129 ], or the use of creative cafes to reaffirm the core values involved in nursing [ 130 ].

4.5.3 Peer support programs

Peer support programs can be effective strategies to support healthcare professionals to help mitigate compassion fatigue. Encouraging individuals to utilise their social support networks has a protective quality, by providing opportunities to process traumatic experiences at work [ 131 ]. Chambers [ 132 ] developed the Care for Caregivers program for physicians, nurses and other frontline staff. The staff were trained in peer support techniques that covered active listening, normalising emotions, reframing situations, sharing stories and offering ideas of coping mechanisms. The program was reported as being well utilised by staff members, especially those dealing with patients experiencing trauma or patient death. Within 2 years of the program running staff surveys reported an increase in feeling adequately supported by the hospital from 16% to 86%, helping change the workplace culture to being more emphatic [ 132 ].

4.5.4 Protection through training

Preventing healthcare from the risks of developing compassion fatigue can be included in training programs. There are ways in training healthcare professionals to equipped them with strategies to help protect them from developing compassion fatigue. For example, trauma therapists utilising evidence-base practices when treating their clients had significantly decreased amounts of compassion fatigue and burnout compared to specialists not using evidence-based practices [ 133 ]. This demonstrates the use of evidence-based practices to prevent the negative outcomes of compassion fatigue therefore improving both the therapists and clients experience of therapy [ 133 , 134 ]. A study by Deighton [ 135 ] reported the exposure to the clients traumatic event was not as important in therapists developing compassion fatigue as the therapist’s t ability to help the client work through their trauma [ 135 ]. Being able to identify possible strategies to be better equipped to deal with exposure to clients’ traumas can reduce the impact on healthcare professionals.

4.5.5 Culture change in healthcare facilities

Organisations can help mitigate the effects of compassion fatigue experienced by their employees. Organisations need to assess whether and to what extent compassion fatigue is a concern of their workers to be able to start to address the problem [ 136 ]. Prevention is recommended as the first line of defence against compassion fatigue [ 137 ]. Organisations should provide regular education and training around the importance of building employees self-care routines [ 138 ]. The Hospital, University Pennsylvania, is an example of an organisation that has provided their own wellness programs to support their staff. A Centre for Nursing Renewal was developed to minimise the ill effects of compassion fatigue and promote wellness among its staff [ 139 ]. The centre offered relaxation, meditation, yoga, group exercise classes, along with other classes and spaces to support nurses emotional and physical wellbeing. The centre assisted in creating a culture where nurse leaders were increasing awareness of nurses experiencing compassion fatigue and burnout and could therefore encourage staff to engage in discussion and renewal practices such as exercise, talking, reflection and getting adequate rest [ 139 ].

Staff wellness programs and initiatives have been implemented and trialled in other health care providers organisations. These programs range in the types of resources provided, include from professional counselling, employee health screening, role modelling, mentor program, o providing healthy snacks and relaxation. These types of programs offered by organisations and led by trained professional can help reduce compassion fatigue [ 119 , 128 ]. These include employee health screening, role modelling, mentor program and staff retreats.

Staff wellness programs and initiatives have been implemented and trialled in other organisations. These programs range in the types of resources provided and included professional counselling, employee health screening, role modelling, mentor program, staff retreats, providing healthy snacks and relaxation. These types of programs were offered by organisations and led by trained professional can help reduce compassion fatigue [ 116 , 125 ].

More practical strategies that could be provided from an organisational level include providing adequate staffing levels, having good leadership support and experienced staff [ 140 ]. By creating workplaces where it is encouraged to acknowledge that providing emphatic care to patients in difficult situations can cause compassion fatigue is a response of caring, can help to address the phenomenon [ 66 ]. At an organisational level demonstrating compassion is genuinely appreciated through celebrating staff acts of compassion [ 136 ] can help make staff feel valued and supported. Providing staff with personal development opportunities promoting psychological wellbeing [ 141 ], along with debriefing after stressful events could promote healing [ 140 ]. Organisations can play a major role in supporting staff provide the best patients care in a safe and nurturing environment.

5. Limitations of this review

While every attempt was made to search the appropriate databases for articles systematically, it is important to note that this is not a systematic review. The search was limited to three major databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), APA PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), and CINAHL Plus using the Boolean/Phrase (Empathy AND (“Compassion Fatigue” OR “Vicarious Trauma”) AND Health). Two main limitations influenced the studies identified by the database search; the first was not including the term “Secondary Traumatic Stress” as an alternative to “Vicarious Trauma” in the search terms, and the second was limiting the search to literature published between 2003 and 2022 and missing essential articles published in the 90s. These dates were initially selected due to the escalation in volume of relevant publications during that timeframe. Fortunately, these limitations were identified by the authors during the review process and were corrected by including all relevant secondary sources which retrieved the essential articles before 2003 in addition to studies examining Secondary Traumatic Stress.

6. Conclusion

Empathy and compassion are fundamental aspirations for HCPs as they provide them with job satisfaction, a sense of value, as well as greatly benefiting their patients. However, caring and supporting people in distress can, over time, lead to compassion fatigue which negatively impacts the healthcare professional, the patient, the organisation, and the healthcare system. Although there are clear risk factors, identifying tools and effective strategies to support and manage those experiencing compassion fatigue, compassion fatigue in HCPs continues to grow reaching alarming levels over the last decade. Further research is needed to quantify the escalation and impact of compassion fatigue, and in a broader array of healthcare professionals. Exploration of the unique impact of loss of compassion beyond the experience of burnout is also an area requiring an enhanced understanding.

We propose that organisations implement regular screening and targeted support for at-risk individuals. More practical strategies could be provided from an organisational level to prevent the development of compassion fatigue in HCPs and support staff to provide the best patient care in a safe and nurturing environment. Ensuring a positive work culture, which includes peer support programs, is a managerial responsibility. Evidence supports the use of formal intervention programs such as CFRP and the ARP to be effective in reducing compassion fatigue, yet these programs required the HCP to commit a substantial amount of time, usually outside of their working day. For the benefits of these programs to reach HCP, shorter programs preferably accessible during work hours could be incorporated. Future research should focus on identifying components of these programs that could be adapted into modified shorter training sessions that could become part of ongoing professional development.

Crucially, we propose that ensuring adequate staffing levels be a key responsibility of management and, therefore, we advise the meticulous implementation of quality assurance, evaluation, and formal reporting of staffing ratios.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the School of Medicine at University of Western Sydney University, Australia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

A special thank you to the medical librarians at Western Sydney University for their literature search and Endnote support.

Nomenclature and abbreviations

healthcare professionals or providers

post-traumatic stress disorder

secondary traumatization

- 1. Roney LN, Acri MC. The cost of caring: An exploration of compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and job satisfaction in pediatric nurses. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2018; 40 :74-80

- 2. Kinman G, Grant L. Enhancing empathy in the helping professions. In: Psychology and neurobiology of empathy. Nova Biomedical Books; 2016. pp. 297-319

- 3. Cole-King A, Gilbert P. Compassionate care: The theory and the reality. Journal of Holistic Healthcare. 2011; 8 (3):30

- 4. Hein G, Singer T. I feel how you feel but not always: The empathic brain and its modulation. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2008; 18 (2):153-158

- 5. Hoffman ML. Chapter 4—Varieties of empathy-based guilt. In: Bybee J, editor. Guilt and Children. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 91-112

- 6. Blumgart HL. Caring for the patient. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1964; 270 :449-456

- 7. Osler W. Aequanimitas: With Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston's Son & Co.; 1920. p. 475

- 8. Markakis K, Frankel R, Beckman H, Suchman A. Teaching empathy: It can be done. Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine; April 29–May 1; San Francisco, California. 1999

- 9. Halpern J. What is clinical empathy? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003; 18 (8):670-674

- 10. Stepien KA, Baernstein A. Educating for empathy. A review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006; 21 (5):524-530

- 11. de Waal FB. The antiquity of empathy. Science. 2012; 336 (6083):874-876

- 12. Radey M, Figley CR. The social psychology of compassion. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2007; 35 (3):207-214

- 13. Joinson C. Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing (Jenkintown, Pa). 1992; 22 (4):116-121

- 14. Figley CR. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in those Who Treat the Traumatized. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1995

- 15. Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists' chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002; 4 (11):1433-1441

- 16. Adams RE, Boscarino JA, Figley CR. Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: A validation study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006; 76 (1):103-108

- 17. Bourassa DB. Compassion fatigue and the adult protective services social worker. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2009; 52 (3):215-229

- 18. Cavanagh N, Cockett G, Heinrich C, Doig L, Fiest K, Guichon JR, et al. Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nursing Ethics. 2020; 27 (3):639-665

- 19. Peters E. Compassion fatigue in nursing: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum (Hillsdale). 2018; 53 (4):466-480

- 20. Sorenson C, Bolick B, Wright K, Hamilton R. Understanding compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A review of current literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2016; 48 (5):456-465

- 21. Bleazard M. Compassion fatigue in nurses caring for medically complex children. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing: JHPN: The Official Journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. 2020; 22 (6):473-478

- 22. Osofsky JD. Perspectives on helping traumatized infants, young children, and their families. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2009; 30 (6):673-677

- 23. Katz A. Compassion in practice: Difficult conversations in oncology nursing. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2019; 29 (4):255-257

- 24. Potter P, Deshields T, Berger JA, Clarke M, Olsen S, Chen L. Evaluation of a compassion fatigue resiliency program for oncology nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013; 40 (2):180-187

- 25. Kinman G, Grant L. Emotional demands, compassion and mental health in social workers. Occupational Medicine. 2020; 70 (2):89-94

- 26. Lemieux-Cumberlege A, Taylor EP. An exploratory study on the factors affecting the mental health and well-being of frontline workers in homeless services. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2019; 27 (4):e367-ee78

- 27. Pietrantoni L, Prati G. Resilience among first responders. African Health Sciences. 2008; 8 (Suppl. 1):S14-S20

- 28. Tehrani N. Compassion fatigue: Experiences in occupational health, human resources, counselling and police. Occupational Medicine. 2010; 60 (2):133-138

- 29. Turgoose D, Glover N, Barker C, Maddox L. Empathy, compassion fatigue, and burnout in police officers working with rape victims. Traumatology. 2017; 23 (2):205-213

- 30. Xie W, Chen L, Feng F, Okoli CTC, Tang P, Zeng L, et al. The prevalence of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2021; 120 :103973

- 31. Anzaldua A, Halpern J. Can clinical empathy survive? Distress, burnout, and malignant duty in the age of Covid-19. Hastings Center Report. 2021; 51 (1):22-27

- 32. Becker J, Dickerman M. Impact of narrative medicine curriculum on burnout in pediatric critical care trainees. Critical Care Medicine. 2021; 49 (1 Suppl. 1):473

- 33. Carver ML. Another look at compassion fatigue. Journal of Christian Nursing: A Quarterly Publication of Nurses Christian Fellowship. 2021; 38 (3):E25-EE7

- 34. Ruiz-Fernández MD, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Ibáñez-Masero O, Cabrera-Troya J, Carmona-Rega MI, Ortega-Galán ÁM. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020; 29 (21-22):4321-4330

- 35. Zhang YY, Han WL, Qin W, Yin HX, Zhang CF, Kong C, et al. Extent of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout in nursing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Nursing Management. 2018; 26 (7):810-819

- 36. Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 2006; 5 (3):101-117

- 37. DiTullio M, MacDonald D. The struggle for the soul of hospice: Stress, coping, and change among hospice workers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 1999; 16 (5):641-655

- 38. Keidel GC. Burnout and compassion fatigue among hospice caregivers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 2002; 19 (3):200-205

- 39. Payne N. Occupational stressors and coping as determinants of burnout in female hospice nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001; 33 (3):396-405

- 40. O'Halloran TM, Linton JM. Stress on the job: Self-care resources for counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2000; 22 (4):354

- 41. Jenaro C, Flores N, Arias B. Burnout and coping in human service practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007; 38 (1):80

- 42. Bride BE, Figley CR. The fatigue of compassionate social workers: An introduction to the special issue on compassion fatigue. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2007; 35 (3):151-153

- 43. Figley CR. Compassion Fatigue: Toward a New Understanding of the Costs of Caring. Philadelphia, PA, US: Brunner/Mazel; 1995

- 44. Rourke MT. Compassion Fatigue in Pediatric Palliative Care Providers. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2007; 54 (5):631-644

- 45. Pfifferling J-H, Gilley K. Overcoming compassion fatigue. Family Practice Management. 2000; 7 (4):39

- 46. Arkan B, Yılmaz D, Düzgün F. Determination of compassion levels of nurses working at a university hospital. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020; 59 (1):29-39

- 47. Zeidner M, Hadar D, Matthews G, Roberts RD. Personal factors related to compassion fatigue in health professionals. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2013; 26 (6):595-609

- 48. Lynch SH, Shuster G, Lobo ML. The family caregiver experience – Examining the positive and negative aspects of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue as caregiving outcomes. Aging & Mental Health. 2018; 22 (11):1424-1431

- 49. Goldblatt H, Buchbinder E. Challenging Gender Roles. Journal of Social Work Education. 2003; 39 (2):255-275

- 50. Gerson JI. The Development of Empathy in the Male Psychotherapist: A Researched Essay. Ohio, United States of America: The Union Institute; 1996

- 51. Kogan I. The role of the analyst in the analytic cure during times of chronic crises. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 2004; 52 (3):735-757

- 52. Batten SV, Orsillo SM. Therapist reactions in the context of collective trauma. The Behavior Therapist. 2002; 25 (2):36-40

- 53. Baum N. Trap of conflicting needs: Helping professionals in the wake of a shared traumatic reality. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2012; 40 (1):37-45

- 54. Ledoux K. Understanding compassion fatigue: Understanding compassion. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2015; 71 (9):2041-2050

- 55. Tanner D. 'The love that dare not speak its Name': The role of compassion in social work practice. British Journal of Social Work. 2020; 50 (6):1688-1705

- 56. Coetzee SK, Klopper HC. Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2010; 12 (2):235-243

- 57. Gilmore C. Compassion fatigue-what it is and how to avoid it. Kai Tiaki: Nursing New Zealand. 2012; 18 (5):32

- 58. Stewart DW. Casualties of war: Compassion fatigue and health care providers. Medsurg Nursing. 2009; 18 (2):91-94

- 59. Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2005

- 60. Wynn F. Burnout or compassion fatigue? A comparative concept analysis for nurses caring for patients in high-stakes environments. International Journal for Human Caring. 2020; 24 (1):59-71

- 61. Zhang Y-Y, Zhang C, Han X-R, Li W, Wang Y-L. Determinants of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burn out in nursing: A correlative meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018; 97 (26):e11086