Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

What Is a Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

Published on February 24, 2023 by Tegan George .

A cohort study is a type of observational study that follows a group of participants over a period of time, examining how certain factors (like exposure to a given risk factor) affect their health outcomes. The individuals in the cohort have a characteristic or lived experience in common, such as birth year or geographic area.

While there are several types of cohort study—including open, closed, and dynamic—there are two that are particularly common: prospective cohort studies and retrospective cohort studies .

The initial cohort consisted of about 18,000 newborns. They were enrolled in the study shortly after birth, with regular follow-ups, medical examinations, and cognitive assessments to track their physical, social, and cognitive development.

Cohort studies are particularly useful for identifying risk factors for diseases. They can help researchers identify potential interventions to help prevent or treat the disease, and are often used in fields like medicine or healthcare research.

Table of contents

When to use a cohort study, examples of cohort studies, advantages and disadvantages of cohort studies, frequently asked questions.

Cohort studies are a type of observational study that can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. They can be used to conduct both exploratory research and explanatory research depending on the research topic.

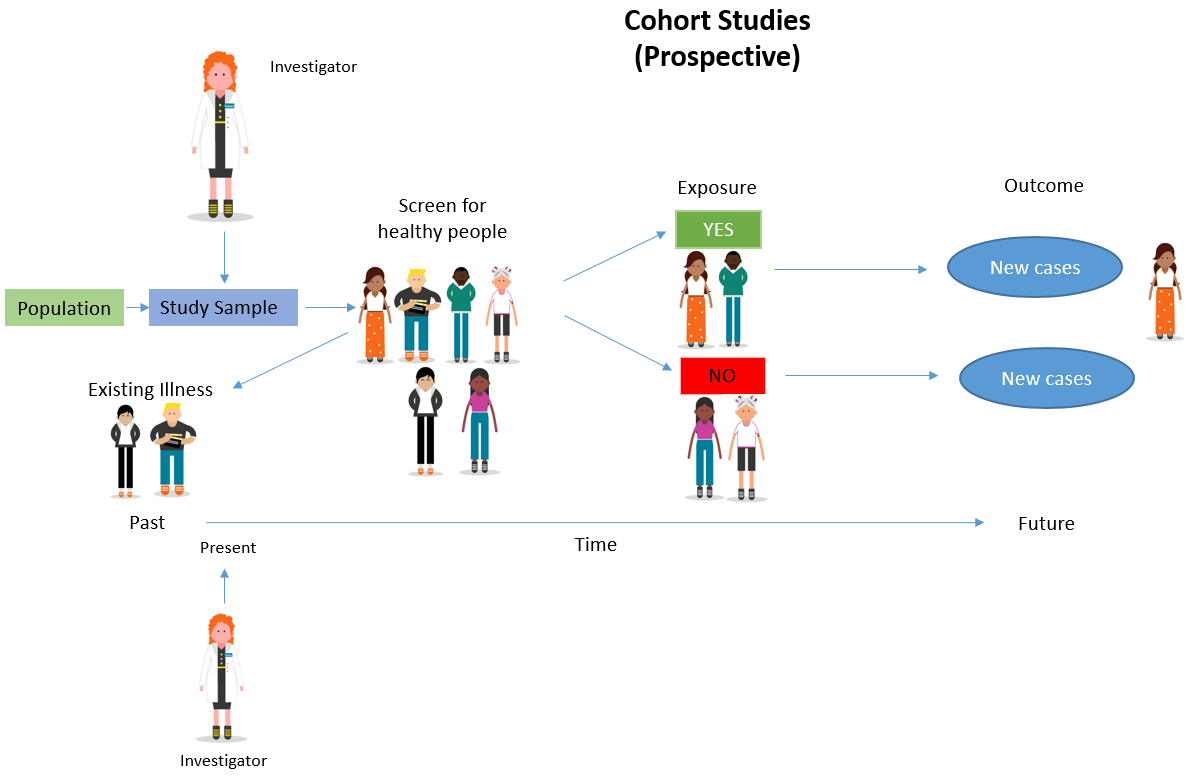

In prospective cohort studies , data is collected over time to compare the occurrence of the outcome of interest in those who were exposed to the risk factor and those who were not. This can help ascertain whether the risk factor could be associated with the outcome.

In retrospective cohort studies , your participants must already possess the disease or health outcome being studied prior to joining. The study is then focused on analyzing the health outcomes of those who share the exposure to the risk factor over a period of time.

A cohort study could be a good fit for your research if:

- You have access to a large pool of research subjects and are comfortable and able to fund research stretching over a longer timeline.

- The relationship between the exposure and health outcome you’re studying is not well understood, and/or its long-term effects have not been thoroughly investigated.

- The exposure you’re studying is rare, or there are possible ethical considerations preventing you from a traditional experimental design .

- Cohort studies in general are more longitudinal in nature. They usually follow the group studied over a long period of time, investigating how certain factors affect their health outcomes.

- Case–control studies rely on primary research , comparing a group of participants already possessing a condition of interest to a control group lacking that condition in real time.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Cohort studies are common in fields like medicine, epidemiology, and healthcare.

Cohort studies are a strong research method , particularly in epidemiology, health, and medicine, but they are not without their disadvantages.

Advantages of cohort studies

Advantages of cohort studies include:

- Cohort studies are better able to approach an estimation of causality than other types of observational studies. Due to their ability to establish temporality, multiple outcomes, and disease incidence over time, researchers are able to determine with more certainty that the exposure indeed preceded the outcome. This strengthens a claim for a cause-and-effect relationship between the variables of interest.

- Due to their long nature, cohort studies are a particularly good choice for studying rare exposures , such as exposure to a new drug or an environmental toxin. Other research designs aren’t able to incorporate the breadth and depth of the impact as broadly as cohort studies do.

- Because cohort studies usually rely on large groups of participants, they are better able to control for potentially confounding variables , such as age, gender identity, or socioeconomic status. Relatedly, the ability to use a sampling method that ensures a more representative sample of the population leads to findings that are typically much more generalizable , with higher internal validity and external validity .

Disadvantages of cohort studies

Disadvantages of cohort studies include:

- Cohort studies can be extremely time-consuming and expensive to conduct due to their long and intense nature.

- Cohort studies are at risk for biases inherent to long-term studies like attrition bias and survivorship bias , as participants are likely to drop out over time. Measurement errors like omitted variable bias and information bias can also confound your analysis, leading you to draw conclusions that may not be true.

- Like many other experimental designs , cohort studies can raise questions regarding ethical considerations . This is particularly the case if the exposure of interest is harmful, or if there is no known treatment for it. Prior to beginning your research, it is critical to ensure that participation in your study is fully voluntary, informed, and as safe as it can be for your research subjects.

The easiest way to remember the difference between prospective and retrospective cohort studies is timing.

- A prospective cohort study moves forward in time, following a group of participants to track the development of an outcome of interest.

- A retrospective cohort study moves backward in time, first identifying a group of people who already possess the outcome of interest, and then looking backwards to assess their exposure to a risk factor.

A closed cohort study is a type of cohort study where all participants are selected at the beginning of the study, with no new participants added during any of the follow-up periods.

This approach is useful when the exposure being studied is rare, or when it isn’t practically or financially feasible to recruit new participants.

In a cohort study , the incidence refers to the number of new cases of a disease or health outcome that develop during the study period, while prevalence refers to the proportion of the population who have the disease or health outcome at a given point in time. Cohort studies are particularly useful for measuring incidence rates.

A dynamic cohort study is a type of cohort study where the participants are not fixed at the start of the study. Instead, new participants can be added over time if they become eligible to participate. This approach is useful when the study population is expected to change over time.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2023, February 24). What Is a Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/cohort-study/

Euser, A. M., Zoccali, C., Jager, K. J., & Dekker, F. W. (2009). Cohort Studies: Prospective versus Retrospective. Nephron Clinical Practice , 113 (3), c214–c217. https://doi.org/10.1159/000235241

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a prospective cohort study | definition & examples, what is a retrospective cohort study | definition & examples, what is an observational study | guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Quantitative study designs: Cohort Studies

Quantitative study designs.

- Introduction

- Cohort Studies

- Randomised Controlled Trial

- Case Control

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Study Designs Home

Cohort Study

Did you know that the majority of people will develop a diagnosable mental illness whilst only a minority will experience enduring mental health? Or that groups of people at risk of having high blood pressure and other related health issues by the age of 38 can be identified in childhood? Or that a poor credit rating can be indicative of a person’s health status?

These findings (and more) have come out of a large cohort study started in 1972 by researchers at the University of Otago in New Zealand. This study is known as The Dunedin Study and it has followed the lives of 1037 babies born between 1 April 1972 and 31 March 1973 since their birth. The study is now in its fifth decade and has produced over 1200 publications and reports, many of which have helped inform policy makers in New Zealand and overseas.

In Introduction to Study Designs, we learnt that there are many different study design types and that these are divided into two categories: Experimental and Observational. Cohort Studies are a type of observational study.

What is a Cohort Study design?

- Cohort studies are longitudinal, observational studies, which investigate predictive risk factors and health outcomes.

- They differ from clinical trials, in that no intervention, treatment, or exposure is administered to the participants. The factors of interest to researchers already exist in the study group under investigation.

- Study participants are observed over a period of time. The incidence of disease in the exposed group is compared with the incidence of disease in the unexposed group.

- Because of the observational nature of cohort studies they can only find correlation between a risk factor and disease rather than the cause.

Cohort studies are useful if:

- There is a persuasive hypothesis linking an exposure to an outcome.

- The time between exposure and outcome is not too long (adding to the study costs and increasing the risk of participant attrition).

- The outcome is not too rare.

The stages of a Cohort Study

- A cohort study starts with the selection of a group of participants (known as a ‘cohort’) sourced from the same population, who must be free of the outcome under investigation but have the potential to develop that outcome.

- The participants must be identical, having common characteristics except for their exposure status.

- The participants are divided into two groups – the first group is the ‘exposure’ group, the second group is free of the exposure.

Types of Cohort Studies

There are two types of cohort studies: Prospective and Retrospective .

How Cohort Studies are carried out

Adapted from: Cohort Studies: A brief overview by Terry Shaneyfelt [video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRasHsoORj0)

Which clinical questions does this study design best answer?

What are the advantages and disadvantages to consider when using a cohort study, what does a strong cohort study look like.

- The aim of the study is clearly stated.

- It is clear how the sample population was sourced, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, with justification provided for the sample size. The sample group accurately reflects the population from which it is drawn.

- Loss of participants to follow up are stated and explanations provided.

- The control group is clearly described, including the selection methodology, whether they were from the same sample population, whether randomised or matched to minimise bias and confounding.

- It is clearly stated whether the study was blinded or not, i.e. whether the investigators were aware of how the subject and control groups were allocated.

- The methodology was rigorously adhered to.

- Involves the use of valid measurements (recognised by peers) as well as appropriate statistical tests.

- The conclusions are logically drawn from the results – the study demonstrates what it says it has demonstrated.

- Includes a clear description of the data, including accessibility and availability.

What are the pitfalls to look for?

- Confounding factors within the sample groups may be difficult to identify and control for, thus influencing the results.

- Participants may move between exposure/non-exposure categories or not properly comply with methodology requirements.

- Being in the study may influence participants’ behaviour.

- Too many participants may drop out, thus rendering the results invalid.

Critical appraisal tools

To assist with the critical appraisal of a cohort study here are some useful tools that can be applied.

Critical appraisal checklist for cohort studies (JBI)

CASP appraisal checklist for cohort studies

Real World Examples

Bell, A.F., Rubin, L.H., Davis, J.M., Golding, J., Adejumo, O.A. & Carter, C.S. (2018). The birth experience and subsequent maternal caregiving attitudes and behavior: A birth cohort study . Archives of Women’s Mental Health .

Dykxhoorn, J., Hatcher, S., Roy-Gagnon, M.H., & Colman, I. (2017). Early life predictors of adolescent suicidal thoughts and adverse outcomes in two population-based cohort studies . PLoS ONE , 12(8).

Feeley, N., Hayton, B., Gold, I. & Zelkowitz, P. (2017). A comparative prospective cohort study of women following childbirth: Mothers of low birthweight infants at risk for elevated PTSD symptoms . Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 101, 24–30.

Forman, J.P., Stampfer, M.J. & Curhan, G.C. (2009). Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women . JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association , 302(4), 401–411.

Suarez, E. (2002). Prognosis and outcome of first-episode psychoses in Hawai’i: Results of the 15-year follow-up of the Honolulu cohort of the WHO international study of schizophrenia . ProQuest Information & Learning, Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering , 63(3-B), 1577.

Young, J.T., Heffernan, E., Borschmann, R., Ogloff, J.R.P., Spittal, M.J., Kouyoumdjian, F.G., Preen, D.B., Butler, A., Brophy, L., Crilly, J. & Kinner, S.A. (2018). Dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance use disorder and injury in adults recently released from prison: a prospective cohort study . The Lancet. Public Health , 3(5), e237–e248.

References and Further Reading

Greenhalgh, T. (2014). How to Read a Paper : The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine , John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, Somerset, United Kingdom.

Hoffmann, T. a., Bennett, S. P., & Mar, C. D. (2017). Evidence-Based Practice Across the Health Professions (Third edition. ed.): Elsevier.

Song, J.W. & Chung, K.C. (2010). Observational studies: cohort and case-control studies . Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery , 126(6), 2234-42.

Mann, C.J. (2003). Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies . Emergency Medicine Journal , 20(1), 54-60.

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Randomised Controlled Trial >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 4:49 PM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/quantitative-study-designs

Prospective Cohort Study Design: Definition & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A prospective study, sometimes called a prospective cohort study, is a type of longitudinal study where researchers will follow and observe a group of subjects over a period of time to gather information and record the development of outcomes.

The participants in a prospective study are selected based on specific criteria and are often free from the outcome of interest at the beginning of the study. Data on exposures and potential confounding factors are collected at regular intervals throughout the study period.

By following the participants prospectively, researchers can establish a temporal relationship between exposures and outcomes, providing valuable insights into the causality of the observed associations.

This study design allows for the examination of multiple outcomes and the investigation of various exposure levels, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing health and disease.

How it Works

Participants are enrolled in the study before they develop the outcome or disease in question and then are observed as it evolves to see who develops the outcome and who does not.

Cohort studies are observational, so researchers will follow the subjects without manipulating any variables or interfering with their environment.

Similar to retrospective studies , prospective studies are beneficial for medical researchers, specifically in the field of epidemiology, as scientists can watch the development of a disease and compare the risk factors among subjects.

Before any appearance of the disease is investigated, medical professionals will identify a cohort, observe the target participants over time, and collect data at regular intervals.

Weeks, months, or years later, depending on the duration of the study design, the researchers will examine any factors that differed between the individuals who developed the condition and those who did not.

They can then determine if an association exists between an exposure and an outcome and even identify disease progression and relative risk.

Determine cause-and-effect relationships

Because researchers study groups of people before they develop an illness, they can discover potential cause-and-effect relationships between certain behaviors and the development of a disease.

Multiple diseases and conditions can be studied at the same time

Prospective cohort studies enable researchers to study causes of disease and identify multiple risk factors associated with a single exposure. These studies can also reveal links between diseases and risk factors.

Can measure a continuously changing relationship between exposure and outcome

Because prospective cohort studies are longitudinal, researchers can study changes in levels of exposure over time and any changes in outcome, providing a deeper understanding of the dynamic relationship between exposure and outcome.

Limitations

Time consuming and expensive.

Prospective studies usually require multiple months or years before researchers can identify a disease’s causes or discover significant results.

Because of this, they are often more expensive than other types of studies. Recruiting and enrolling participants is another added cost and time commitment.

Requires large subject pool

Prospective cohort studies require large sample sizes in order for any relationships or patterns to be meaningful. Researchers are unable to generate results if there is not enough data.

- Framingham Heart Study: Studied the effects of diet, exercise, and medications on the development of hypertensive or arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease in residents of the city of Framingham, Massachusetts.

- Caerphilly Heart Disease Study: Examined relationships between a wide range of social, lifestyle, dietary, and other factors with incident vascular disease.

- The Million Women Study: Analyzed data from more than one million women aged 50 and over to understand the effects of hormone replacement therapy use on women’s health.

- Nurses’ Health Study: Studied the effects of diet, exercise, and medications on the development of hypertensive or arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

- Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Mortality: Determined whether sleep-disordered breathing and its sequelae of intermittent hypoxemia and recurrent arousals are associated with mortality in a community sample of adults aged 40 years or older (Punjabi et al., 2009)

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what does it mean when an observational study is prospective.

A prospective observational study is a type of research where investigators select a group of subjects and observe them over a certain period.

The researchers collect data on the subjects’ exposure to certain risk factors or interventions and then track the outcomes. This type of study is often used to study the effects of suspected risk factors that cannot be controlled experimentally.

2. What is the primary difference between a randomized clinical trial and a prospective cohort study?

In a retrospective study, the subjects have already experienced the outcome of interest or developed the disease before the start of the study.

The researchers then look back in time to identify a cohort of subjects before they had developed the disease and use existing data, such as medical records, to discover any patterns.

In a prospective study, on the other hand, the investigators will design the study, recruit subjects, and collect baseline data on all subjects before any of them have developed the outcomes of interest.

The subjects are followed and observed over a period of time to gather information and record the development of outcomes.

3. What is the primary difference between a randomized clinical trial and a prospective cohort study?

In randomized clinical trials , the researchers control the experiment, whereas prospective cohort studies are purely observational, so researchers will observe subjects without manipulating any variables or interfering with their environment.

Researchers in randomized clinical trials will randomly divide participants into groups, either an experimental group or a control group.

However, in prospective cohort studies, researchers will identify a cohort and observe the target participants as a whole to examine any factors that differ between the individuals who develop the condition and those who do not.

Euser, A. M., Zoccali, C., Jager, K. J., & Dekker, F. W. (2009). Cohort studies: prospective versus retrospective. Nephron. Clinical practice, 113(3), c214–c217. https://doi.org/10.1159/000235241

Hariton, E., & Locascio, J. J. (2018). Randomised controlled trials – the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 125(13), 1716. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15199

Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis-2 Study Group de Mutsert Renée r. de_mutsert@ lumc. nl Grootendorst Diana C Boeschoten Elisabeth W Brandts Hans van Manen Jeannette G Krediet Raymond T Dekker Friedo W. (2009). Subjective global assessment of nutritional status is strongly associated with mortality in chronic dialysis patients. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89(3), 787-793.

Punjabi, N. M., Caffo, B. S., Goodwin, J. L., Gottlieb, D. J., Newman, A. B., O”Connor, G. T., Rapoport, D. M., Redline, S., Resnick, H. E., Robbins, J. A., Shahar, E., Unruh, M. L., & Samet, J. M. (2009). Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS medicine, 6(8), e1000132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000132

Ranganathan, P., & Aggarwal, R. (2018). Study designs: Part 1 – An overview and classification. Perspectives in clinical research, 9(4), 184–186.

Song, J. W., & Chung, K. C. (2010). Observational studies: cohort and case-control studies. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 126(6), 2234–2242. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f44abc.

Further Information

- Euser, A. M., Zoccali, C., Jager, K. J., & Dekker, F. W. (2009). Cohort studies: prospective versus retrospective. Nephron Clinical Practice, 113(3), c214-c217.

- Design of Prospective Studies

- Hammoudeh, S., Gadelhaq, W., & Janahi, I. (2018). Prospective cohort studies in medical research (pp. 11-28). IntechOpen.

- Nabi, H., Kivimaki, M., De Vogli, R., Marmot, M. G., & Singh-Manoux, A. (2008). Positive and negative affect and risk of coronary heart disease: Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Bmj, 337.

- Bramsen, I., Dirkzwager, A. J., & Van der Ploeg, H. M. (2000). Predeployment personality traits and exposure to trauma as predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms: A prospective study of former peacekeepers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(7), 1115-1119.

How to choose your study design

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Medicine, Sydney Medical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

- PMID: 32479703

- DOI: 10.1111/jpc.14929

Research designs are broadly divided into observational studies (i.e. cross-sectional; case-control and cohort studies) and experimental studies (randomised control trials, RCTs). Each design has a specific role, and each has both advantages and disadvantages. Moreover, while the typical RCT is a parallel group design, there are now many variants to consider. It is important that both researchers and paediatricians are aware of the role of each study design, their respective pros and cons, and the inherent risk of bias with each design. While there are numerous quantitative study designs available to researchers, the final choice is dictated by two key factors. First, by the specific research question. That is, if the question is one of 'prevalence' (disease burden) then the ideal is a cross-sectional study; if it is a question of 'harm' - a case-control study; prognosis - a cohort and therapy - a RCT. Second, by what resources are available to you. This includes budget, time, feasibility re-patient numbers and research expertise. All these factors will severely limit the choice. While paediatricians would like to see more RCTs, these require a huge amount of resources, and in many situations will be unethical (e.g. potentially harmful intervention) or impractical (e.g. rare diseases). This paper gives a brief overview of the common study types, and for those embarking on such studies you will need far more comprehensive, detailed sources of information.

Keywords: experimental studies; observational studies; research method.

© 2020 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (The Royal Australasian College of Physicians).

- Case-Control Studies

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Research Design*

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Braunwald's Corner

- ESC Guidelines

- EHJ Dialogues

- Issue @ a Glance Podcasts

- CardioPulse

- Weekly Journal Scan

- European Heart Journal Supplements

- Year in Cardiovascular Medicine

- Asia in EHJ

- Most Cited Articles

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EHJ?

- Open Access Options

- Submit from medRxiv or bioRxiv

- Author Resources

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Journals Career Network

- About European Heart Journal

- Editorial Board

- About the European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- War in Ukraine

- ESC Membership

- ESC Journals App

- Developing Countries Initiative

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, conclusions, acknowledgements, supplementary data, declarations, data availability, ethical approval, pre-registered clinical trial number.

- < Previous

Human papillomavirus infection and cardiovascular mortality: a cohort study

Yoosoo Chang and Seungho Ryu contributed equally as co-corresponding authors.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Hae Suk Cheong, Yoosoo Chang, Yejin Kim, Min-Jung Kwon, Yoosun Cho, Bomi Kim, Eun-Jeong Joo, Young Ho Bae, Chanmin Kim, Seungho Ryu, Human papillomavirus infection and cardiovascular mortality: a cohort study, European Heart Journal , Volume 45, Issue 12, 21 March 2024, Pages 1072–1082, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae020

- Permissions Icon Permissions

High-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) infection—a well-established risk factor for cervical cancer—has associations with cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, its relationship with CVD mortality remains uncertain. This study examined the associations between HR-HPV infection and CVD mortality.

As part of a health examination, 163 250 CVD-free Korean women (mean age: 40.2 years) underwent HR-HPV screening and were tracked for up to 17 years (median: 8.6 years). National death records identified the CVD mortality cases. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for CVD mortality were estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression analyses.

During 1 380 953 person-years of follow-up, 134 CVD deaths occurred, with a mortality rate of 9.1 per 10 5 person-years for HR-HPV(−) women and 14.9 per 10 5 person-years for HR-HPV(+) women. After adjustment for traditional CVD risk factors and confounders, the HRs (95% CI) for atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), ischaemic heart disease (IHD), and stroke mortality in women with HR-HPV infection compared with those without infection were 3.91 (1.85–8.26), 3.74 (1.53–9.14), and 5.86 (0.86–40.11), respectively. The association between HR-HPV infection and ASCVD mortality was stronger in women with obesity than in those without ( P for interaction = .006), with corresponding HRs (95% CI) of 4.81 (1.55–14.93) for obese women and 2.86 (1.04–7.88) for non-obese women.

In this cohort study of young and middle-aged Korean women, at low risks for CVD mortality, those with HR-HPV infection had higher death rates from CVD, specifically ASCVD and IHD, with a more pronounced trend in obese individuals.

High-risk human papillomavirus infection and cardiovascular mortality. HR, hazard ratio; HR-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus infection; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Human papilloma virus and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease’, by N.C. Chan, https://doi.org10.1093/eurheartj/ehad829 .

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the world’s leading cause of death, accounting for an estimated 17.9 million deaths (32% of all global deaths) in 2019, with this number projected to increase to 23.6 million by 2030. 1–3 Despite considerable advancements in the management strategies targeting conventional CVD risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, dyslipidaemia, high blood pressure, and diabetes, CVD remains a leading cause of death and disability. 3–6 Furthermore, these conventional risk factors alone do not completely explain the high incidence and prevalence of CVD, 3 with ∼20% of CVD cases lacking these conventional risk factors. 7 Identifying modifiable non-conventional risk factors of CVD is, therefore, crucial in developing optimal preventive and treatment strategies for reducing CVD.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a sexually transmitted infection, 8 with a prevalence rate of 2%–44% in the general female population. 9 High-risk strains of HPV (HR-HPV) infection are well-established causative agents of anogenital cancers in women. 10 Several cross-sectional studies have suggested a possible association between HR-HPV and atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD). 9 , 11 Our recent prospective cohort study supports this association in new-onset CVD. 12 However, no cohort studies have evaluated the long-term CVD outcomes associated with HR-HPV infection.

Understanding the contribution of HR-HPV infection to long-term cardiovascular consequences in women with HPV may have important clinical significance, particularly considering the availability of HPV vaccines. 13 Thus, we conducted a large-scale cohort study of Korean women who underwent a HR-HPV test as part of a health screening programme to verify our hypothesis that HR-HPV infection in women is associated with increased CVD mortality, with potential effect modification by obesity.

Study design and participants

The Kangbuk Samsung Health Study is a cohort study of Korean adults aged 18 years or older who underwent annual or biennial health examinations at the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Healthcare Centers in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea. 12 , 14 Data were collected as part of health screening examinations, which included questionnaires, blood tests, and imaging examinations. 14

The study population comprised women aged ≥30 years who underwent a comprehensive health screening examination between 2004 and 2018 ( n = 178 854). The final sample size was 163 250 after we excluded 15 604 participants who met the following criteria ( Figure 1 ): unknown vital status due to invalid identifiers, missing data on body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, lipid profiles, glucose, insulin, or high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels, as well as history of CVD, hysterectomy, or cancer.

Selection process of the study population

The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the use of de-identified data obtained as part of routine health screening examinations. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (KBSMC 2022-05-029).

Measurements

Demographic characteristics, health behaviours, medical history, and medication use were assessed as a basic part of the health examinations using standardized, self-administered questionnaires, as previously described. 14 Smoking status was classified as never, former, or current. Alcohol consumption was categorized as ≤20 or >20 g/day. Regular exercise was defined as engaging in vigorous physical activity at least three times per week. 14 , 15 The assessment of weekly vigorous physical activity frequency varied over time: (i) from 2004 to 2008, it was based on activities inducing perspiration; (ii) in 2009–10, it focused on vigorous activities like running, aerobics, fast bicycling, or hiking that made participants breathe much harder than normal; and (iii) starting in 2011, the validated Korean version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form was used for this assessment. 16 , 17 A high level of education is characterized by having a college graduate degree or higher.

Trained nurses measured the participants’ height, weight, and blood pressure. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m 2 according to Asian-specific criteria. 18 Hypertension was defined based on systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or the current use of blood pressure–lowering medications.

Blood samples were drawn from the antecubital vein after a minimum 10 h fast. Blood tests included total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides, alanine transaminase (ALT), fasting glucose, insulin, and hsCRP. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as fasting insulin (mg/dL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/405. Diabetes mellitus was assessed according to fasting serum glucose levels ≥126 mg/dL, glycated haemoglobin levels ≥6.5%, self-reports of a previous diagnosis, or the use of blood glucose–lowering agents.

High-risk human papillomavirus tests were performed as part of cervical cancer screening, using cervical specimens, and all samples were analysed in a core laboratory located at Kangbuk Samsung hospital. 12 From 2004 until April 2016, the HR Hybrid Capture 2 assay (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used for HR-HPV testing, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The HR Hybrid Capture 2 is a sandwich-capture molecular hybridization assay that utilizes chemiluminescence detection to provide a semi-quantitative result. Specifically, the assay denatures HPV DNA and then hybridizes single-stranded HPV DNA with a mixture of single-stranded, full-genomic-length RNA probes that are specific for 13 HR-HPV genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68). The results were considered negative if the measurements were below the relative light-unit cut-off of 1.0. After April 2016, the Roche Cobas HPV assay was used for HR-HPV testing. This is a fully automated real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay that involves DNA extraction and purification using a Cobas ×480 Instrument (Roche Molecular Systems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), followed by real-time PCR amplification and type-specific hybridization that is performed by the Cobas z480 Analyzer (Roche Molecular Systems). The assay utilizes a mixture of primer pairs and probes to amplify and detect the 14 HR-HPV DNAs. The results were considered as positive when the cycle threshold was <40.0. The result is reported as either negative or positive for HPV16 and HPV18 and as a pooled result for the other 12 HR-HPVs (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68). To maintain quality control (QC), two QC materials with positive and negative controls provided by the manufacturer were included in each run. Moreover, prior to replacing an obsolete analyser with a new one in the laboratory, a performance evaluation was conducted to ensure that the samples could be successfully validated for precision and comparisons of quantitative measurements based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines EP5 and EP12-A2. During the majority of study periods, the measurement of HR-HPV did not differentiate between Types 16 and 18 and the other HR-HPV types. Therefore, for the analysis, HR-HPV positivity was categorized as binary (HR-HPV negative vs. HR-HPV positive). Both HR-HPV testing procedures in this study were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for HR-HPV screening and were subjected to rigorous QC measures to ensure accuracy and reliability of the results. 19

The Framingham Risk Score (FRS) was calculated based on age, smoking status (current, past, or never), diabetes mellitus (absence or presence), systolic blood pressure (mmHg), HDL-C concentration (mg/dL), and total cholesterol concentration (mg/dL). The 10-year risk of developing CVD was considered low if the result was <10%. 20

Mortality follow-up

We followed up on mortality until the end of 2020 using nationwide death certificate data from the Korea National Statistical Office. Because all deaths of Koreans must be reported to the Korea National Statistical Office, death certificate data for Korean adults are virtually complete. To determine the cause of death, we used the single most relevant underlying cause of death as identified by the Korean National Statistical Office and classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (10th revision) (ICD-10). The concordance rate between the causes of death listed on death certificates and the patient diagnoses in the medical utilization data was in the range of 72.2%–91.9%. 21 , 22 Circulatory system disease ICD-10 I00–I99 was used to define CVD mortality, while ASCVD mortality was defined by ICD-10 I20–I25, I63–I64, G45, and I70–I74. The mortality data were further divided into the following causes of death: ischaemic heart disease (IHD, I20–25); ischaemic stroke [I63–64, no death caused due to transient cerebral ischaemic attacks (G45)]; peripheral artery disease (I70–I74); and other CVDs except for ASCVD (I codes except for the ASCVD codes stated above). 23 , 24

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint was CVD mortality, including its subtypes. We followed each participant from their baseline examination until the occurrence of CVD death or until the end of 2020, whichever occurred first. Participants who died of other causes were censored on the date of death. Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for CVD mortality. Using age as the timescale, the age of subjects was recorded at their first health check-up exam (left truncation) and the age at which subjects exited the analysis, either at the time of death or on 31 December 2020. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by examining the graphs of the estimated log–log survival; no violation of the assumption was found.

Initially, the models were adjusted for age (timescale), and then, these were further adjusted for confounding variables between HR-HPV and CVD mortality, including the centre attended (Seoul or Suwon); year of screening exam; BMI; smoking (never, past, current, or unknown); alcohol intake (0, <20, ≥20 g/day, or unknown); regular exercise (no, yes, or unknown); education level (<community college graduate, ≥community college graduate, or unknown); history of diabetes; history of hypertension; and lipid-lowering medication use (Model 1). Model 2 was further adjusted for triglycerides, LDL-C, HDL-C, HOMA-IR, and hsCRP. As obesity is associated with an increased risk of HPV infection or its persistence, 25 , 26 to examine whether the associations between HR-HPV and CVD mortality differ according to the presence of obesity, we performed a stratified analysis according to the presence of obesity (defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m 2 according to Asian-specific criteria). Furthermore, an additional analysis stratified according to FRS categories (FRS < 10% vs. FRS ≥ 10% 20 ) was performed to assess whether the associations are modified by traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

To account for competing risks, a counterfactual framework to define the marginal cumulative incidence (net risk) was employed, which represents the risk under elimination of competing events. 27 This estimation was carried out using the parametric g -formula method. In this assessment, we examined each distinct cause of death separately, while considering deaths unrelated to the specific cause as alternative competing risks. For instance, when assessing cardiovascular deaths through the g -formula approach, non-cardiovascular deaths were treated as competing risks.

To address the potential imbalance in characteristics between participants with and without HPV infection and enhance comparability between the two groups, we calculated the propensity score for HPV infection. These individual scores were then utilized to more effectively address the existing imbalance between the two groups. 28 , 29 We employed two analytical approaches: inverse probability weights (IPWs) and covariate adjustment using propensity scores. 28 We estimated the probability of HPV infection as a function of the baseline characteristics and used these probabilities to assign weights to each individual in the analysis. Each individual was weighted by the inverse of the predicted probability of HPV infection.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis including data from women with a history of cervical cancer who had undergone HPV testing, despite being initially excluded from the main analysis due to the potential removal of the cervix (which is the primary site of HPV infection) via hysterectomy.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 17.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and R version 4.3.0. All reported P -values were two-tailed, with P < .05 considered statistically significant.

The mean age ± standard deviation (SD) and mean BMI ± SD of the 163 250 participants were 40.2 ± 9.7 years and 22.0 ± 3.1 kg/m 2 , respectively. The prevalence rate of HR-HPV infections was 9.2%. High-risk human papillomavirus infection was positively associated with age, current smoking status, alcohol intake, regular exercise, history of hypertension, history of diabetes, blood pressure, HDL-C, ALT, and HOMA-IR, whereas it was inversely associated with education level, use of lipid-lowering medications, LDL-C, and hsCRP ( Table 1 ).

Estimated a mean values (95% confidence interval) and adjusted a proportions (95% confidence interval) of the baseline characteristics of the study participants according to high-risk human papillomavirus status

CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; BP, blood pressure; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance.

a Adjusted for age.

b BMI ≥ 25 kg/m 2 .

c ≥20 g of ethanol per day.

d ≥3 times per week.

e ≥College graduate.

Table 2 shows the association between HR-HPV positivity and CVD mortality rates. During 1 380 953 person-years of follow-up, 134 CVD deaths occurred, resulting in a mortality rate of 9.7 per 10 5 person-years (refer to Supplementary data online , Table S1 for specific disease code information related to CVD deaths). The median follow-up was 8.6 years (inter-quartile range: 5.4–11.5). High-risk human papillomavirus infection was significantly associated with an increased risk of ASCVD and IHD mortality; however, no significant association was observed between HR-HPV infection and mortality due to ischaemic stroke or other forms of CVD, aside from ASCVD ( Figure 2 ). The multivariable-adjusted HRs (95% CI) for ASCVD and IHD mortality were 3.56 (1.67–7.56) and 3.36 (1.37–8.25), respectively, for participants who were HR-HPV–positive compared with those who were HR-HPV–negative. Upon additional adjustment for triglycerides, LDL-C, HDL-C, HOMA-IR, and hsCRP, the associations remained consistent. Treating HR-HPV and potential confounders as time-varying variables resulted in stronger associations between HR-HPV infections and overall circulatory system disease, ASCVD, and IHD mortality compared with those of time-fixed models ( Table 2 ). In our study, where we conducted five separate tests, we applied Bonferroni adjustment, considering a score as significant only if the corresponding P -value was ≤α/5. The association between HR-HPV and ASCVD/IHD mortality remained significant, even after Bonferroni correction (see Supplementary data online , Table S2 ).

A Kaplan–Meier curve of cumulative mortality of cardiovascular disease mortality by human papillomavirus positivity: ( A ) circulatory system disease, ( B ) atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, ( C ) ischaemic heart disease, ( D ) ischaemic stroke, and ( E ) other circulatory system diseases except for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. CVD, cardiovascular disease; HPV, human papillomavirus; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease

Hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for cardiovascular disease mortality according to high-risk human papillomavirus status

HPV, human papillomavirus; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; BMI, body mass index; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

a Estimated from the Cox proportional hazards model with age as a timescale to estimate HRs and 95% CIs. The multivariable model was adjusted for age (timescale), centre, year of screening examination, smoking status, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, BMI, education level, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, and use of medication for hyperlipidaemia; Model 2: the same factors used in Model 1 plus an adjustment for triglycerides, LDL-C, HDL-C, HOMA-IR, and hsCRP.

b Estimated from the proportional hazard model with HPV status, smoking, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, BMI, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, and use of medication for hyperlipidaemia as time-dependent categorical variables and baseline sex, centre, year of screening, and education level as time-fixed variables.

In the counterfactual framework for the marginal cumulative incidence (net risk), the risk under HR-HPV infection for ASCVD mortality was significantly higher than the risk without HR-HPV infection (see Supplementary data online , Table S3 and Figure S1 ). Specifically, risk differences (%) at year 10 were as follows: 0.080 (95% CI: 0.018–0.250) for ASCVD mortality, 0.036 (95% CI: 0.000–0.115) for IHD mortality, and 0.014 (95% CI: −0.006–0.104) for ischaemic stroke mortality.

In sensitivity analyses using propensity score, the results obtained using either IPWs or covariate adjustment were found to be very similar to those obtained without using propensity score analyses (see Supplementary data online , Table S4 ). In sensitivity analyses including women with a history of cervical cancer, the prevalence of HPV infection was 11.2%, which was higher compared with that of the group without a history of cervical cancer (9.2%). In this analysis, no cardiovascular deaths occurred among the women with cervical cancer. The results, including those with a history of cervical cancer, yielded similar findings. Notably, the association between HR-HPV infection and ASCVD mortality remained statistically significant (see Supplementary data online , Table S5 ).

When stratified by obesity status, a trend was observed towards stronger associations between HR-HPV and CVD mortality (especially ASCVD mortality) in the obese group (defined as BMI ≥ 25 kg/m 2 ) compared with the non-obese group. The multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI) for ASCVD mortality when comparing HR-HPV–positive participants with HR-HPV–negative participants was 4.81 (1.55–14.93) in the obese group, whereas the corresponding HR (95% CI) was 2.86 (1.04–7.88) in the non-obese group ( P for interaction = .006; Table 3 and Figure 3 ). No such patterns were observed for mortality from other forms of CVD, aside from ASCVD.

A Kaplan–Meier curve of cumulative mortality of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease mortality by human papillomavirus positivity among ( A ) non-obese and ( B ) obese women. CVD, cardiovascular disease; HPV, human-papillomavirus; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease

Hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for cardiovascular disease mortality according to high-risk human papillomavirus status by obesity

CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; HR, hazard ratio; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease.

a Estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model with age as a timescale to estimate HRs and 95% CIs. The multivariate model was adjusted for age (timescale), centre, year of screening examination, smoking status, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, education level, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, and use of medication for hyperlipidaemia.

When stratified by FRS (FRS < 10% and FRS ≥ 10%, see Supplementary data online , Table S6 ), significantly elevated risks of ASCVD and IHD mortality were found in individuals positive for HR-HPV, regardless of their FRS group.

In this large-scale cohort study of 163 250 apparently healthy young and middle-aged women without pre-existing CVD, the absolute risks of CVD mortality were low. However, those with HR-HPV infection had a higher rate of deaths attributed to CVD mortality, specifically ASCVD and IHD mortality. These associations remained significant even after adjusting for CVD risk factors and other possible confounders. The strength of this association was greater in women with obesity, indicating that the relationship between HR-HPV infection and CVD mortality may be modified by obesity ( Structured Graphical Abstract ).

Recent research has expanded its focus beyond HPV’s association with cancer development, and accumulating epidemiological evidence suggests that HPV is associated with CVD risk. A cross-sectional study conducted in the USA found that women with genital HPV infection, especially HR-HPV, had a nearly three-fold higher history of myocardial infarction or stroke compared with that in women without HPV. 11 However, this study was limited by their cross-sectional design, use of self-collected samples of HPV, and/or reliance on self-reported outcome data. Another study found that patients with head and neck cancer who tested positive for HPV had a four-fold increased risk of stroke. 30 In a previous cohort study, we demonstrated that young Korean women infected with HR-HPV, as ascertained by clinician-collected samples, were at elevated risk of CVD events, especially those who were obese and metabolically unhealthy. 12 Nonetheless, no studies have examined the association between HR-HPV and long-term CVD outcomes to our knowledge. The present study extends our earlier work on HR-HPV and CVD by demonstrating that HR-HPV infection is associated with an increased risk of CVD mortality, particularly due to ASCVD or IHD. We did not directly examine the association among HPV infection, non-fatal CVD, and CVD mortality within a single dataset. However, the collective evidence from these two studies suggests that HPV infection may indeed act as a risk factor for the development of non-fatal CVD and contribute to poor prognosis, ultimately leading to CVD mortality. Several factors contribute to an elevated risk of cardiovascular mortality. Firstly, HPV is not recognized as a cardiovascular risk factor, and effective strategies for managing HPV infections in relation to cardiovascular complications are lacking. Additionally, there is a notable absence of antiviral drugs designed specifically for HPV treatment as well as a lack of pharmaceutical interventions targeting inflammation, which is a potential mechanism through which HPV increases cardiovascular events.

Chronic infection has emerged as a non-conventional risk factor of unexplained cardiovascular events, and recent studies suggest that it may play a role in the development of atherosclerosis. 13 , 31 Recently, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 has been shown to cause direct myocardial injury, and worsen pre-existing CVD, potentially leading to an increased risk of cardiovascular complications and mortality. 32 , 33 Although there is relatively limited evidence on the relationship between HR-HPV and atherosclerotic processes compared with other viral pathogens, our findings support the notion that the connection between HPV and increased CVD risks is likely mediated by the involvement of HPV in ASCVD. 34 HPV may promote atherogenesis by infecting vascular cells or non-vascular cells and inducing systemic inflammation. 35–37 Contrary to the traditional belief that HPV replicates only locally and has limited systemic effects, several reports have demonstrated that HPV DNA can be isolated from white blood cells in circulating blood, both in healthy blood donors and patients with HPV-associated cancers; thus, this suggests that HPV may reach arterial structures via the bloodstream. 35 , 38 , 39 HPV infection may also accelerate atherogenesis by eliciting a persistent inflammatory response and systemic inflammation. 35–37

In our study, the association between HR-HPV and ASCVD mortality remained even after adjustment for hsCRP levels (a well-established low-grade inflammatory biomarker) and lipid profiles (including triglycerides, LDL-C, and HDL-C levels). Although it is uncertain whether the observed associations are due to effects beyond inflammation, hsCRP (despite being a predictor of atherosclerotic risk) is unlikely to be causally involved in atherogenic pathways. 40 While the inflammatory role in CVD is crucial, 41 investigating the mechanistic pathogenesis of CVD based on the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerosis suggests that gaining insights by moving upstream in the inflammatory cascade from hsCRP to interleukin (IL)-6 to IL-1 could be valuable. 42 Indeed, clinical trials and mechanistic studies suggest that colchicine and other anti-inflammatory agents targeting upstream inflammatory markers, such as IL-1 and IL-6, have potential atheroprotective effects. 42–44 Thus, future research should explore upstream markers (such as IL-1 and IL-6) to gain a better understanding of the connection among HR-HPV, inflammation, atherosclerotic progression, and CVD mortality.

The present study found a stronger association between HR-HPV and CVD mortality in obese individuals compared with that in non-obese individuals, which is consistent with our previous study results where obesity modified the association between HR-HPV and incident CVD. 12 The mechanisms explaining this association have been previously discussed, 12 with suggestions including compromised immune responses to HPV infection due to obesity-associated metabolic abnormalities and obesity-induced systemic inflammation, which exacerbate the atherosclerotic process and contribute to the risk of CVD and CVD mortality in conjunction with HPV. 45 , 46

In the stratified analyses based on the FRS, the excess relative risks of ASCVD and IHD mortality in HPV-positive individuals with respect to HPV-negative individuals were similar in both the FRS < 10% and FRS ≥ 10% groups, with a four-fold increase in risk. Thus, based on traditional risk factors, HR-HPV infection poses an additional risk of CVD mortality, even in low-risk individuals. Particularly, the limitations of the FRS include the underestimation of coronary heart disease risk in women, in whom up to 20% of coronary artery diseases that occur are unrelated to these traditional risk factors. 7 , 47 The observed associations between HR-HPV and ASCVD mortality, strongly modified by obesity than by the conventional risk factors assessed by the FRS, suggest that chronic systemic inflammation may constitute a key pathogenic mechanism in HPV–CVD dynamics, 34 as inflammation is also a primary mediator linking obesity and CVD. 48 Further mechanistic studies are required to confirm these findings.

In sensitivity analyses including women with a history of cervical cancer, the association between HR-HPV infection and ASCVD mortality remained statistically significant. No cardiovascular deaths were observed among the subjects with cervical cancer, limiting further assessment of cervical cancer, HPV infection, and CVD risk. However, it is important to note that the number of subjects with cervical cancer in our study was only 734 patients, potentially limiting its ability to assess the relationship among HPV infection, cervical cancer, and their association with CVD risk. To further investigate the persistence of HPV infection in patients with treated cervical cancer and its potential association with cardiovascular events, future studies with a larger sample size specifically focused on this population and incorporating measures of HPV persistence are warranted.

Human papillomavirus vaccines have been widely introduced since 2007 and have been effective in preventing HPV-related cancers and benign conditions. 49 , 50 In countries with high vaccine uptake, HPV vaccination programmes have also been effective in reducing the risk of HPV 16 and 18 infection (up to an 83% reduction), as well as the risk of anogenital warts (up to a 67% reduction) and cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia 2 (up to a 51% reduction). 50 In a recent analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination, it was reported that significant associations between vaginal HPV infection and CVD were not observed among HPV-vaccinated women. 51 Although it remained unclear in the study whether the loss of the pathogenic activities of HPV in women post-vaccination reduced the risk of CVD or whether the vaccine itself had direct cardioprotective effects via some unknown mechanism, the findings, together with ours, potentially suggest that HPV risk reduction through vaccination may have benefits in preventing adverse long-term CVD outcomes. Human papillomavirus vaccination is recommended before sexual debut for both sexes and has been approved for selective therapy in older adults. 49 Successful national HPV vaccination campaigns may reduce not only HPV-related cancers but also CVD and CVD-related mortality. Future longitudinal studies should further evaluate the potential benefits of HPV vaccination or treatment in reducing CVD mortality.

Our study had several limitations. First, we lacked information on the duration of exposure to HR-HPV infection before the baseline visit, which precluded lifetime HPV infection status assessment, including initial infection, regression, and persistence. Second, we did not identify specific HR-HPV genotypes, low-risk HPV infection cases, or cervical pathology data. We also lacked data on the vaccination status and type-specific HPV genotypes of the vaccinated women in this study. In Korea, the quadrivalent and bivalent HPV vaccines have been approved for use in women aged 9–26 since 2007 and 2008, respectively. Human papillomavirus vaccination was initially introduced in South Korea as part of the National Immunization Program in 2016 targeting 12-year-old girls. 52 Considering that our study included female participants with a mean age of 40.2 ± 9.7 years who attended a health check-up programme between 2004 and 2018, it is reasonable to assume that the HPV vaccination rate among individuals in our study might be relatively low. Furthermore, the prevalence of HPV 16 and HPV 18, the most aggressive oncogenic strains covered by the HPV vaccine, may have decreased over time as vaccine uptake increased, whereas the prevalence of other non-vaccine HPV subtypes may not differ or may be slightly lower between vaccinated and non-vaccinated women. 53 , 54 This could result in an underestimation of the association between the most oncogenic HR-HPV types (16 and 18) and CVD mortality. Third, our study population consisted of young and middle-aged Korean women with relatively high socioeconomic statuses and education levels, in whom the HR-HPV prevalence rate was 9.2%, similar to the 8.4% reported based on health check-ups in Korean women 55 but lower than the overall prevalence rate of 14%–19% in US women aged 30 years or older. 56 Thus, it is important to acknowledge that the findings of this study are limited to Korean women, and caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to other populations. The study focused on HR-HPV testing as part of a health examination exclusively for women, while HPV testing is not routinely performed in men. However, a previous study involving patients with head and neck cancer, predominantly males (74.9%), discovered that HPV-positive status was linked to an increased risk of stroke or transient ischaemic attack. 30 This implies that HPV infection may also be considered a risk factor for CVD in men as well. In recent years, the significance of HPV testing and vaccination in men for the prevention and early detection of HPV-related diseases has been increasingly recognized. 57 Given the high prevalence of HPV infection in both men and women, it is crucial to further investigate whether HPV infection serves as an unconventional risk factor in CVD development and prognosis, considering larger and more diverse populations. Fourth, the relatively small number of CVD deaths in the study sample may have constrained the statistical power to detect significant associations. Furthermore, despite the relative risk for ASCVD mortality being 3.5 times higher in HPV-positive women compared with HPV-negative women, it is crucial to note that the absolute risk for these outcomes is small among these relatively healthy and young individuals, equalling to 7.1 deaths per 100.000 person-years of follow-up. It is also important to clarify that this study did not establish a causal relationship between HR-HPV infection and CVD mortality. Further research is needed to confirm these findings through studies involving different populations with varied demographics, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and comorbidities.

In this large cohort study of young and middle-aged Korean women, who have low absolute risks of CVD mortality, we identified a positive association between HR-HPV infection and elevated risk of CVD mortality, particularly among individuals with obesity. Our findings suggest that HR-HPV infection, especially when combined with obesity, may be associated with an increased risk of CVD mortality. Considering the absence of specific antiviral drugs targeting HPV and the limited pharmaceutical interventions for inflammation associated with HPV, further research is warranted to explore potential vaccine strategies aimed at reducing HR-HPV infection and the potential use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the context of HPV-associated CVD, with the goal of mitigating CVD mortality and improving patient outcomes.

We express our gratitude to the staff of the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study for their diligent efforts, unwavering commitment, and ongoing support.

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal online.

Disclosure of Interest

All authors declare no disclosure of interest for this contribution.

The data will not be made publicly available owing to our institutional review board’s regulations. However, the analytical methods are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This study was supported by the SKKU Excellence in Research Award Research Fund (Sungkyunkwan University, 2022).

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (KBSMC 2022-05-029).

Not applicable.

Roth GA , Forouzanfar MH , Moran AE , Barber R , Nguyen G , Feigin VL , et al . Demographic and epidemiologic drivers of global cardiovascular mortality . N Engl J Med 2015 ; 372 : 1333 – 41 . https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1406656

Google Scholar

Timmis A, Vardas P, Townsend N, Torbica A, Katus H, De Smedt D, et al . European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. Eur Heart J 2022; 43 :716–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab892

Benjamin EJ , Blaha MJ , Chiuve SE , Cushman M , Das SR , Deo R , et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association . Circulation 2017 ; 135 : e146 – 603 . https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485

Piepoli MF , Hoes AW , Agewall S , Albus C , Brotons C , Catapano AL , et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) . Eur Heart J 2016 ; 37 : 2315 – 81 . https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106

Arnett DK , Blumenthal RS , Albert MA , Buroker AB , Goldberger ZD , Hahn EJ , et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines . Circulation 2019 ; 140 : e596 – 646 . https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

Visseren FLJ , Mach F , Smulders YM , Carballo D , Koskinas KC , Back M , et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice . Eur Heart J 2021 ; 42 : 3227 – 337 . https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484

Khot UN , Khot MB , Bajzer CT , Sapp SK , Ohman EM , Brener SJ , et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease . JAMA 2003 ; 290 : 898 – 904 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.7.898

Satterwhite CL , Torrone E , Meites E , Dunne EF , Mahajan R , Ocfemia MC , et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008 . Sex Transm Dis 2013 ; 40 : 187 – 93 . https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53

Brito LMO , Brito HO , Correa R , de Oliveira Neto CP , Costa JPL , Monteiro SCM , et al. Human papillomavirus and coronary artery disease in climacteric women: is there an association? ScientificWorldJournal 2019 ; 2019 : 1872536 . https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1872536

Koshiol J , Lindsay L , Pimenta JM , Poole C , Jenkins D , Smith JS . Persistent human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Am J Epidemiol 2008 ; 168 : 123 – 37 . https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn036

Kuo HK , Fujise K . Human papillomavirus and cardiovascular disease among U.S. women in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003 to 2006 . J Am Coll Cardiol 2011 ; 58 : 2001 – 6 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.038

Joo EJ , Chang Y , Kwon MJ , Cho A , Cheong HS , Ryu S . High-risk human papillomavirus infection and the risk of cardiovascular disease in Korean women . Circ Res 2019 ; 124 : 747 – 56 . https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313779

Muhlestein JB . Chronic infection and coronary atherosclerosis. Will the hypothesis ever really pan out? J Am Coll Cardiol 2011 ; 58 : 2007 – 9 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.015

Chang Y , Ryu S , Choi Y , Zhang Y , Cho J , Kwon MJ , et al. Metabolically healthy obesity and development of chronic kidney disease: a cohort study . Ann Intern Med 2016 ; 164 : 305 – 12 . https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-1323

Haskell WL , Lee IM , Pate RR , Powell KE , Blair SN , Franklin BA , et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association . Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007 ; 39 : 1423 – 34 . https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27

Craig CL , Marshall AL , Sjostrom M , Bauman AE , Booth ML , Ainsworth BE , et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity . Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003 ; 35 : 1381 – 95 . https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

Chun MY . Validity and reliability of Korean version of international physical activity questionnaire short form in the elderly . Korean J Fam Med 2012 ; 33 : 144 – 51 . https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2012.33.3.144

World Health Organization Western Pacific Region . The Asia-Pacific Perspective: Redefining Obesity and Its Treatment . Sydney : Health Communications Australia , 2000 .

Google Preview

cobas HPV test . https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf10/p100020s017c.pdf (28 February 2023, date last accessed).

D’Agostino RB Sr , Vasan RS , Pencina MJ , Wolf PA , Cobain M , Massaro JM , et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study . Circulation 2008 ; 117 : 743 – 53 . https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579

Song YM , Sung J . Body mass index and mortality: a twelve-year prospective study in Korea . Epidemiology 2001 ; 12 : 173 – 9 . https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200103000-00008

Won TY , Kang BS , Im TH , Choi HJ . The study of accuracy of death statistics . J Korean Soc Emerg Med 2007 ; 18 : 256 – 62 . http://www.jksem.org/journal/view.php?number=924

Kim KS , Hong S , Han K , Park CY . Assessing the validity of the criteria for the extreme risk category of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a nationwide population-based study . J Lipid Atheroscler 2022 ; 11 : 73 – 83 . https://doi.org/10.12997/jla.2022.11.1.73

Lee HH , Cho SMJ , Lee H , Baek J , Bae JH , Chung WJ , et al. Korea heart disease fact sheet 2020: analysis of nationwide data . Korean Circ J 2021 ; 51 : 495 – 503 . https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2021.0097

Molokwu JC , Penaranda E , Lopez DS , Dwivedi A , Dodoo C , Shokar N . Association of metabolic syndrome and human papillomavirus infection in men and women residing in the United States . Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017 ; 26 : 1321 – 7 . https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0129

Huang X , Zhao Q , Yang P , Li Y , Yuan H , Wu L , et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cervical human papillomavirus incident and persistent infection . Medicine (Baltimore) 2016 ; 95 : e2905 . https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002905

Young JG , Stensrud MJ , Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ , Hernan MA . A causal framework for classical statistical estimands in failure-time settings with competing events . Stat Med 2020 ; 39 : 1199 – 236 . https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8471

Austin PC . An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies . Multivariate Behav Res 2011 ; 46 : 399 – 424 . https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

Rosenbaum PR , Rubin DB . The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects . Biometrika 1983 ; 70 : 41 – 55 . https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

Addison D , Seidelmann SB , Janjua SA , Emami H , Staziaki PV , Hallett TR , et al. Human papillomavirus status and the risk of cerebrovascular events following radiation therapy for head and neck cancer . J Am Heart Assoc 2017 ; 6 : e006453 . https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006453

Pothineni NVK , Subramany S , Kuriakose K , Shirazi LF , Romeo F , Shah PK , et al. Infections, atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease . Eur Heart J 2017 ; 38 : 3195 – 201 . https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx362

Tobler DL , Pruzansky AJ , Naderi S , Ambrosy AP , Slade JJ . Long-term cardiovascular effects of COVID-19: emerging data relevant to the cardiovascular clinician . Curr Atheroscler Rep 2022 ; 24 : 563 – 70 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-022-01032-8

Aleksova A , Fluca AL , Gagno G , Pierri A , Padoan L , Derin A , et al. Long-term effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality . Life Sci 2022 ; 310 : 121018 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2022.121018

Tonhajzerova I , Olexova LB , Jurko A Jr , Spronck B , Jurko T , Sekaninova N , et al. Novel biomarkers of early atherosclerotic changes for personalised prevention of cardiovascular disease in cervical cancer and human papillomavirus infection . Int J Mol Sci 2019 ; 20 : 3720 . https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20153720

Hemmat N , Ebadi A , Badalzadeh R , Memar MY , Baghi HB . Viral infection and atherosclerosis . Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018 ; 37 : 2225 – 33 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3370-z

Lawson JS , Glenn WK , Tran DD , Ngan CC , Duflou JA , Whitaker NJ . Identification of human papilloma viruses in atheromatous coronary artery disease . Front Cardiovasc Med 2015 ; 2 : 17 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2015.00017

Manzo-Merino J , Massimi P , Lizano M , Banks L . The human papillomavirus (HPV) E6 oncoproteins promotes nuclear localization of active caspase 8 . Virology 2014 ; 450–451 : 146 – 52 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2013.12.013

Bodaghi S , Wood LV , Roby G , Ryder C , Steinberg SM , Zheng ZM . Could human papillomaviruses be spread through blood? J Clin Microbiol 2005 ; 43 : 5428 – 34 . https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.11.5428-5434.2005

Foresta C , Bertoldo A , Garolla A , Pizzol D , Mason S , Lenzi A , et al. Human papillomavirus proteins are found in peripheral blood and semen Cd20+ and Cd56+ cells during HPV-16 semen infection . BMC Infect Dis 2013 ; 13 : 593 . https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-593

Elliott P , Chambers JC , Zhang W , Clarke R , Hopewell JC , Peden JF , et al. Genetic loci associated with C-reactive protein levels and risk of coronary heart disease . JAMA 2009 ; 302 : 37 – 48 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.954

Ridker PM , Bhatt DL , Pradhan AD , Glynn RJ , MacFadyen JG , Nissen SE , et al. Inflammation and cholesterol as predictors of cardiovascular events among patients receiving statin therapy: a collaborative analysis of three randomised trials . Lancet 2023 ; 401 : 1293 – 301 . https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00215-5

Ridker PM . From C-reactive protein to interleukin-6 to interleukin-1: moving upstream to identify novel targets for atheroprotection . Circ Res 2016 ; 118 : 145 – 56 . https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306656

Ridker PM , Everett BM , Thuren T , MacFadyen JG , Chang WH , Ballantyne C , et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease . N Engl J Med 2017 ; 377 : 1119 – 31 . https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1707914

Nidorf SM , Fiolet ATL , Mosterd A , Eikelboom JW , Schut A , Opstal TSJ , et al. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease . N Engl J Med 2020 ; 383 : 1838 – 47 . https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021372

Henning RJ . Obesity and obesity-induced inflammatory disease contribute to atherosclerosis: a review of the pathophysiology and treatment of obesity . Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2021 ; 11 : 504 – 29 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8449192/

Scott M , Nakagawa M , Moscicki AB . Cell-mediated immune response to human papillomavirus infection . Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001 ; 8 : 209 – 20 . https://doi.org/10.1128/CDLI.8.2.209-220.2001

Ridker PM , Buring JE , Rifai N , Cook NR . Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the Reynolds Risk Score . JAMA 2007 ; 297 : 611 – 9 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.6.611

Khafagy R , Dash S . Obesity and cardiovascular disease: the emerging role of inflammation . Front Cardiovasc Med 2021 ; 8 : 768119 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.768119

Dilley S , Miller KM , Huh WK . Human papillomavirus vaccination: ongoing challenges and future directions . Gynecol Oncol 2020 ; 156 : 498 – 502 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.10.018

Drolet M , Benard E , Perez N , Brisson M ; HPV Vaccination Impact Study Group . Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis . Lancet 2019 ; 394 : 497 – 509 . https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30298-3

Liang X , Chou OHI , Cheung BMY . The effects of human papillomavirus infection and vaccination on cardiovascular diseases, NHANES 2003–2016 . Am J Med 2023 ; 136 : 294 – 301.e2 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.09.021