JSTOR Daily’s Archives of Art History

Our editors have rounded up a collection of stories about art, artists, museums, and the way (and why) we study them.

Over the past decade, our writers and editors have shared dozens of stories, research summaries, and reading lists on the history of art. We’ve covered individual artists, movements and manifestos, research methods, and museum practices. As a body, these stories reflect the interests of our writers, of course, but they also capture important events in the art world and shifts in methodological trends. And some of them shine a light (but not too brightly—we follow best archival practices here) on overlooked artists and artworks.

We’ve gathered dozens of stories from our archives to inspire, educate, and entertain. They’re loosely categorized by movement or period, but if you have a compelling argument for recategorization, please do let us know (it’s possible our categories could lead to some heated conversations in a historiography and methods seminar).

As always, the research articles linked in the stories and marked with a red J icon are free to read and download.

The Ancient World

Vulture Cultures

Reinterpreting The Chauvet Cave Paintings

Renaissance, baroque, mannerism, northern renaissance.

How Renaissance Art Found Its Way to American Museums

Fruit and Veg: The Sexual Metaphors of the Renaissance

The Renaissance Lets Its Hair Down

How Did Michelangelo Get So Good?

Taking Liberties With Biblical Stories

Restoration Recipes

Who Was the Little Girl in Las Meninas ?

The Lumpy Pearls That Enchanted the Medicis

Jan van der Heyden and the Dawn of Efficient Street Lights

How Buon Fresco Brought Perspective to Drawing

The 17th-Century Dutch Version of Bookstagram

500 Years of Hell With Hieronymus Bosch

Picturing Christina of Denmark

The Climate Canvasses of the Little Ice Age

Delts Don’t Lie

Alexander Calder, Sculptor

The Didarganj Figurine: A Yakshi or a Ganika ?

How Sculptor Meta Warrick Challenged White Supremacy

Fake Stone and the Georgian Ladies Who Made It

Why Are Cities Filled with Metal Men on Horseback?

These Gravity-Defying Sculptures Provoked Accusations of Demonic Possession

Nineteenth century (pre-raphaelites, academic, romanticism).

Peat’s Place in Art

Who Were the Male Models in French History Paintings?

Elizabeth siddal, the real-life “ophelia”.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s Personal #Brand

The Same-Sex Household That Launched 3 Women Artists

Marking the Grave of the First African American Landscape Artist

Did North America’s Longest Painting Inspire Moby-Dick ?

When Landscape Painting Was Protest Art

Caroline Louisa Daly Is Finally Getting Her Due

Haunted Soldiers in Mesopotamia

Rosa Bonheur’s Permission to Wear Pants

Subscription Art for the 19th-Century Set

Nineteenth century (impressionism, post-impressionism).

The Art of Impressionism: A Reading List

Framing Degas

How Impressionist Berthe Morisot Painted Women’s Lives

Why We Connect with Vincent van Gogh’s Paintings

The Controversial Backstory of London’s Most Lavish Room

Experiencing Monet’s Giverny

Photography.

Art, Technology, & Early Photography: William Henry Fox Talbot

Marie Cosindas and the Painterly Photograph

How Photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White Showed Apartheid to Americans

Kwame Brathwaite Showed the World that Black is Beautiful

Challenging Race and Gender Roles, One Photo at a Time

The Photographers Who Captured the Great Depression

From Folkway to Art: The Transformation of Quilts

The Genius of Georgette Chen

Who Belonged to the Beaver Hall Group?

How the Rothko Chapel Creates Spiritual Space

The Rise and Fall of Hologram Art

Why John Baldessari Burned His Own Art

This British Suffragist Used Her Art for Activism

The Mystery behind Charlotte Salomon’s Groundbreaking Art

The Colonialist Gaze of Matisse’s Odalisques

Painter, Proust Scholar, P.O.W.

When Dole Sent Georgia O’Keeffe to Hawaii

The American Art Style that Idolized the Machine

Did Frida Kahlo Suffer From Fibromyalgia?

Was Marsden Hartley Really a Great Painter?

How to Talk About Diego Rivera and Mexican Art

Francis Picabia’s Chameleonic Style

Remembering Maud Lewis

The “Refus Global”

Black in the USSR

Elena Guro and the Cubo-Futurism Group

Art Nouveau: Art of Darkness

The Triumphant Return of Jacob Lawrence

Visiting “Soul of a Nation”

Surrealism, dada.

Painting Race

How René Magritte Became the Grudging Father of Pop Art

Victor Hugo: Surrealist Artist

Dalí, Surrealism and…Fashion Magazines?

DADA at 100, or, I Zimbra!

Surrealism at 100: A Reading List

Late twentieth century (pop, post modernism, street).

Feminist Art History: An Introductory Reading List

Why David Hockney Makes Both Paintings and Photographs

Power in the Painting: Faith Ringgold and her Story Quilts

The Global Rise of Street Art

The Women of Pop

How Basquiat Used His Surroundings as a Canvas

Andy Warhol from A to B and Back Again

Printmaking.

Country Roads and City Scenes in Japanese Woodblock Prints

Under Hokusai’s Great Wave

Museums, methods, and more.

How Black Artists Fought Exclusion in Museums

The Other Monuments Men

Metadata for Image Search and Discovery

Lady with an Ermine Meets Nazi Art Thief Hans Frank

Our Obsession with Art Heists

Alfred Stieglitz’s Art Journal

The Claude Glass Revolutionized the Way People Saw Landscapes

Preventing Art Fraud In Today’s Art Market

What About the Art in “Apesh*t”?

Making Egypt’s Museums

Olympic Art: Mega Events and the Museum

Saving Art from the Revolution, for the Revolution

The Mystery of the Mona Lisa

AI and the Creative Process: Part One

Linda Nochlin on “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists”

How to Find and Choose the Best Images for Your Project

How to Look at Art and Understand What You See

The Benin Bronzes and the Cultural History of Museums

The Origins of the Feminist Art Movement

How 1971’s Womanhouse Shaped Today’s Feminist Art

How an Unrealized Art Show Created an Archive of Black Women’s Art

Wait, Why Are the Parthenon Marbles in London?

How Museums Tidy Up

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- Can You Photograph a Ghost?

- Judy-Lynn del Rey

- Ghosts in the Machine

How to Be a British Villain

Recent posts.

- Ghost of the Forest: Monotropa uniflora

- Inventing Silk Roads

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Discover the story of art and global culture through The Met collection. Funded by the Heilbrunn Foundation, New Tamarind Foundation, and Zodiac Fund.

Explore more than 1,000 essays on a wide range of topics, including artists, materials, movements, and themes.

Andean Textiles

For centuries prior to the Spanish Conquest, Andean textiles were used to express status and identity.

Allegories of the Four Continents

European artists from the Renaissance onward have visualized the known world through allegorical figures.

Works of Art

Browse a selection of more than 8,000 works from the collection.

Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise

Giovanni di Paolo

Untitled Film Still #21

Cindy Sherman

Chronologies

Trace the global evolution of art and culture across millennia.

Ancient Greece, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

China, 500–1000 A.D.

Eastern Africa, 1600–1800 A.D.

Discover connections across time and cultures through more than 150 essays and 800 works of art in this book inspired by the Timeline .

What is art history and where is it going?

Peter Paul Rubens, three paintings from the 24-picture cycle Rubens painted for the Medici Gallery in the Luxembourg Palace, Paris. From left to right: Peter Paul Rubens, The Presentation of the Portrait of Marie de’ Medici , The Wedding by Proxy of Marie de’ Medici to King Henry IV , Arrival (or Disembarkation) of Marie de’ Medici at Marseilles , 1621–25, oil on canvas (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Art history might seem like a relatively straightforward concept: “art” and “history” are subjects most of us first studied in elementary school. In practice, however, the idea of “the history of art” raises complex questions. What exactly do we mean by art, and what kind of history (or histories) should we explore? Let’s consider each term further.

Art versus artifact

The word “art” is derived from the Latin ars , which originally meant “skill” or “craft.” These meanings are still primary in other English words derived from ars , such as “artifact” (a thing made by human skill) and “artisan” (a person skilled at making things). The meanings of “art” and “artist,” however, are not so straightforward. We understand art as involving more than just skilled craftsmanship. What exactly distinguishes a work of art from an artifact, or an artist from an artisan?

When asked this question, students typically come up with several ideas. One is beauty. Much art is visually striking, and in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, the analysis of aesthetic qualities was indeed central in art history. During this time, art that imitated ancient Greek and Roman art (the art of classical antiquity ), was considered to embody a timeless perfection. Art historians focused on the so-called fine arts—painting, sculpture, and architecture—analyzing the virtues of their forms. Over the past century and a half, however, both art and art history have evolved radically.

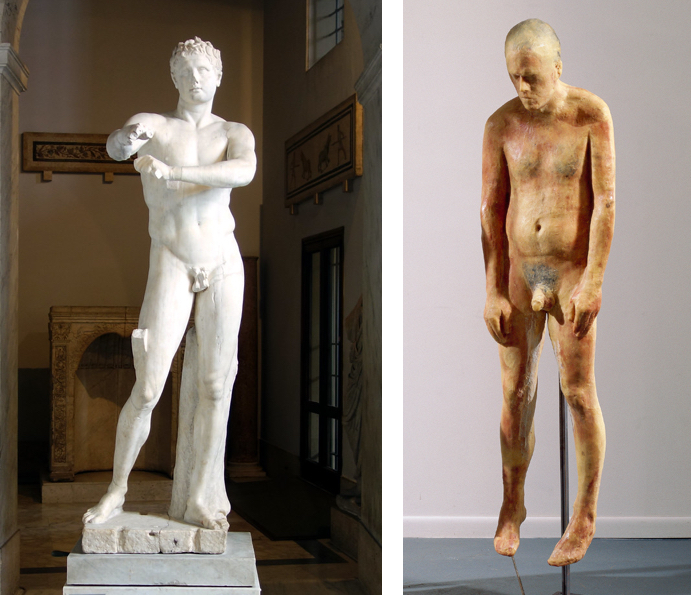

Left: Lysippos, Apoxyomenos (Scraper) , Roman copy after a bronze statue from c. 330 B.C.E., 81 inches high (Vatican Museums, photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Kiki Smith, male figure from Untitled , 1990, 198.1 x 181.6 x 54 cm, beeswax and microcrystalline wax figures on metal stands (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) © Kiki Smith

Artists turned away from the classical tradition , embracing new media and aesthetic ideals, and art historians shifted their focus from the analysis of art’s formal beauty to interpretation of its cultural meaning. Today we understand beauty as subjective—a cultural construct that varies across time and space. While most art continues to be primarily visual, and visual analysis is still a fundamental tool used by art historians, beauty itself is no longer considered an essential attribute of art.

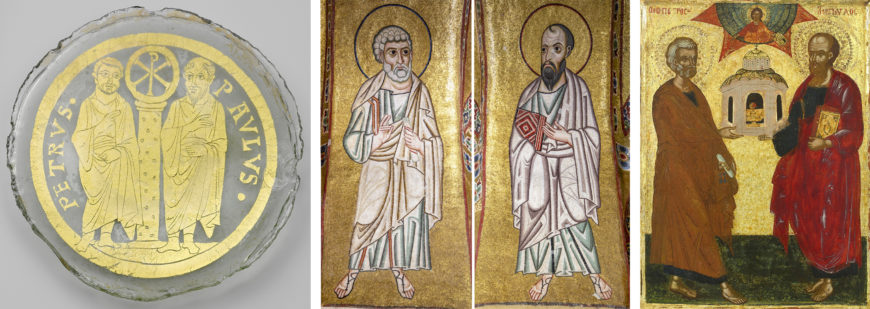

Images of Peter and Paul appear much the same through the centuries in Byzantine icons. Left: glass bowl base, 4th century, Roman ( The Metropolitan Museum of Art ); center: mosaics, 11th century, Hosios Loukas Monastery, Greece; right: panel icon, 17th century, Greek ( Temple Gallery ).

A second common answer to the question of what distinguishes art emphasizes originality, creativity, and imagination. This reflects a modern understanding of art as a manifestation of the ingenuity of the artist. This idea, however, originated five hundred years ago in Renaissance Europe , and is not directly applicable to many of the works studied by art historians. For example, in the case of ancient Egyptian art or Byzantine icons , the preservation of tradition was more valued than innovation. While the idea of ingenuity is certainly important in the history of art, it is not a universal attribute of the works studied by art historians.

All this might lead one to conclude that definitions of art, like those of beauty, are subjective and unstable. One solution to this dilemma is to propose that art is distinguished primarily by its visual agency, that is, by its ability to captivate viewers. Artifacts may be interesting, but art, I suggest, has the potential to move us—emotionally, intellectually, or otherwise. It may do this through its visual characteristics (scale, composition, color, etc.), expression of ideas, craftsmanship, ingenuity, rarity, or some combination of these or other qualities. How art engages varies, but in some manner, art takes us beyond the everyday and ordinary experience. The greatest examples attest to the extremes of human ambition, skill, imagination, perception, and feeling. As such, art prompts us to reflect on fundamental aspects of what it is to be human. Any artifact, as a product of human skill, might provide insight into the human condition. But art, in moving beyond the commonplace, has the potential to do so in more profound ways. Art, then, is perhaps best understood as a special class of artifact, exceptional in its ability to make us think and feel through visual experience.

Coatlicue , c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza Mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

History: Making Sense of the Past

Like definitions of art and beauty, ideas about history have changed over time. It might seem that writing history should be straightforward—it’s all based on facts, isn’t it? In theory, yes, but the evidence surviving from the past is vast, fragmentary, and messy. Historians must make decisions about what to include and exclude, how to organize the material, and what to say about it. In doing so, they create narratives that explain the past in ways that make sense in the present. Inevitably, as the present changes, these narratives are updated, rewritten, or discarded altogether and replaced with new ones. All history, then, is subjective—as much a product of the time and place it was written as of the evidence from the past that it interprets.

The discipline of art history developed in Europe during the colonial period (roughly the 15th to the mid-20th century). Early art historians emphasized the European tradition, celebrating its Greek and Roman origins and the ideals of academic art . By the mid-20th century, a standard narrative for “Western art” was established that traced its development from the prehistoric , ancient , and medieval Mediterranean to modern Europe and the United States . Art from the rest of the world, labeled “non-Western art,” was typically treated only marginally and from a colonialist perspective.

The immense sociocultural changes that took place in the 20th century led art historians to amend these narratives. Accounts of Western art that once featured only white males were revised to include artists of color and women. The traditional focus on painting, sculpture, and architecture was expanded to include so-called minor arts such as ceramics and textiles and contemporary media such as video and performance art . Interest in non-Western art increased, accelerating dramatically in recent years.

Queen Mother Pendant Mask (Iyoba), 16th century, Edo peoples, Court of Benin, Nigeria, ivory, iron, copper, 23.8 x 12.7 x 8.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Today, the biggest social development facing art history is globalism. As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, familiarity with different cultures and facility with diversity are essential. Art history, as the story of exceptional artifacts from a broad range of cultures, has a role to play in developing these skills. Now art historians ponder and debate how to reconcile the discipline’s European intellectual origins and its problematic colonialist legacy with contemporary multiculturalism and how to write art history in a global era.

Smarthistory’s videos and articles reflect this history of art history. Since the site was originally created to support a course in Western art and history, the content initially focused on the most celebrated works of the Western canon . With the key periods and civilizations of this tradition now well-represented and a growing number of scholars contributing, the range of objects and topics has increased in recent years. Most importantly, substantial coverage of world traditions outside the West has been added. As the site continues to expand, the works and perspectives presented will evolve in step with contemporary trends in art history. In fact, as innovators in the use of digital media and the internet to create, disseminate, and interrogate art historical knowledge, Smarthistory and its users have the potential to help shape the future of the discipline.

Important fundamentals

“ Introduction: Learning to look and think critically ,” a chapter in Reframing Art History (our free art history textbook).

“ Introduction: Close looking and approaches to art ,” a chapter in Reframing Art History (our free art history textbook)—especially useful for materials related to formal (visual) analysis.

Check out all the chapters on world art in Reframing Art History .

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Virtual Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Policy

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Publish with Art History?

- About Art History

About the Association for Art History

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Editor

Lucy Bradnock

Deputy Editor

Rebecca Wade

Reviews Editor

Fiona Anderson

Managing Editor

Samuel Bibby

Hear from Editor Lucy Bradnock about the mission, vision, and priorities of the journal.

More about the journal

Through advocacy, events, networks, membership, grants and publications, the Association for Art History celebrates and promotes the value of art history and visual culture today.

Keep up with new articles

Register to receive email alerts from Art History as soon as new content from the journal is published online.

Virtual issues

To complement our on-going programme of special issues, Art History has commissioned a number of scholars to draw together thematic collections of articles to form virtual issues of the journal.

Access the virtual issues

Author resources

Learn about how to submit your article, our publishing process, and tips on how to promote your article.

Submit your research

Read the instructions for authors to learn how to prepare your manuscript for publication.

Access the instructions

Frequently asked questions

Read our frequently asked questions before submitting your work.

Developing countries initiative

Your institution could be eligible to free or deeply discounted online access to Art History through the Oxford Developing Countries Initiative.

Related titles

- Recommend to your Library

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1467-8365

- Print ISSN 0141-6790

- Copyright © 2024 Association for Art History

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

art history, historical study of the visual arts, being concerned with identifying, classifying, describing, evaluating, interpreting, and understanding the art products and historic development of the fields of painting, sculpture, architecture, the decorative arts, drawing, printmaking, photography, interior design, etc.

The history of art focuses on objects made by humans for any number of spiritual, narrative, philosophical, symbolic, conceptual, documentary, decorative, and even functional and other purposes, but with a primary emphasis on its aesthetic visual form.

Over the past decade, our writers and editors have shared dozens of stories, research summaries, and reading lists on the history of art. We’ve covered individual artists, movements and manifestos, research methods, and museum practices.

Art history is an interdisciplinary practice that analyzes the various factors—cultural, political, religious, economic or artistic—which contribute to visual appearance of a work of art. Art historians employ a number of methods in their research into the ontology and history of objects.

The brilliant histories of art belong to everyone, no matter their background. Smarthistory’s free, award-winning digital content unlocks the expertise of hundreds of leading scholars, making the history of art accessible and engaging to more people, in more places, than any other publisher. About Smarthistory. Smarthistory's blog.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Discover the story of art and global culture through The Met collection. Funded by the Heilbrunn Foundation, New Tamarind Foundation, and Zodiac Fund.

At the most basic level, art historians analyze function by identifying types—an altarpiece, portrait, Book of Hours, tomb, palace, etc. Studying the history and use of a given type provides a context for understanding specific examples.

Art historians focused on the so-called fine arts—painting, sculpture, and architecture—analyzing the virtues of their forms. Over the past century and a half, however, both art and art history have evolved radically.

Art History, the journal of the Association for Art History, is an international, refereed journal that promotes world-class art-historical scholarship from across the globe. Learn more.

The Dignity of Every Human Being: New Brunswick Artists and Canadian Culture between the Great Depression and the Cold War. 2015. Dimensions of Aesthetic Encounters: Perception, Interpretation, and the Signs of Art. 2022.