Études caribéennes

Home Numéros 16 Problématiques caribéennes The Importance of Reggae Music in...

The Importance of Reggae Music in the Worldwide Cultural Universe

When reggae emerged in the late 1960s, it came as a cultural bombshell not only to Jamaica but the whole world. Reggae has influenced societies throughout the world, contributing to the development of new counterculture movements, particularly in Europe, in the USA and Africa. Indeed, by the end of the 1960s, it participated in the birth of the skinhead movement in the UK. In the 1970s, it impacted on Western punk rock/ pop cultures and inspired the first rappers in the USA. Finally, since the late 1970s onwards, it has also influenced singers originating from Africa, Alpha Blondy, Tiken Jah Fakoly and Lucky Dube being perfect examples. Thus, my paper will examine the impact of Jamaican reggae music on the worldwide cultural universe, especially on Europe, the USA and Africa.

Lorsque le reggae émergea à la fin des années 1960, il eut un impact culturel considérable non seulement à la Jamaïque, mais à travers le monde. Le reggae a influencé les sociétés du monde entier, contribuant au développement de nouveaux mouvements contre-culturels, en particulier en Europe, aux États-Unis et en Afrique. En effet, à la fin des années 1960, il concourut à la naissance du mouvement skinhead au Royaume-Uni. Dans les années 1970, il eut un impact certain sur les cultures punk rock/ pop occidentales et inspira les premiers rappeurs aux États-Unis. Enfin, depuis la fin des années 1970, il influence également de nombreux chanteurs originaires d’Afrique, Alpha Blondy, Tiken Jah Fakoly et Lucky Dube étant de parfaits exemples. Ainsi, cet essai se propose d’étudier l’impact du reggae jamaïcain dans l’univers culturel mondial, notamment en Europe, aux États-Unis et en Afrique.

Index terms

Keywords : , keywords: , geographical index: , introduction.

1 Reggae is the musical genre which revolutionized Jamaican music. When it emerged in the late 1960s, it came as a cultural bombshell not only to Jamaica but the whole world. Its slow jerky rhythm, its militant and spiritual lyrics as well as the rebellious appearance of its singers, among others, have influenced musical genres, cultures and societies throughout the world, contributing to the development of new counterculture movements, especially in Europe, in the USA and Africa. Indeed, by the end of the 1960s, it participated in the birth of the skinhead movement in the UK. In the 1970s, it impacted on Western punk rock/ pop cultures, influencing artists like Eric Clapton and The Clash. During the same decade, it inspired the first rappers in the USA, giving rise to hip-hop culture. Finally, since the end of the 1970s, it has also influenced singers originating from Africa, the Ivorian singers Alpha Blondy and Tiken Jah Fakoly, and the South African Lucky Dube clearly illustrating this point. Thus, my paper will examine the impact of reggae music on the worldwide cultural universe, focusing particularly on Europe, the USA and Africa.

1. The Impact of Reggae Music on Europe

1.1. the british case.

- 1 Sound systems emerged in the late 1940s in Kingston’s ghettos. This subculture appeared for precise (...)

2 “Between 1953 and 1962 […] approximately 175, 000 Jamaicans from town and country boarded the banana boats destined for London, Liverpool and other British ports” (Chevannes 1994: 263). And despite the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, the immigration of Jamaicans to the UK, especially England, remained rather significant throughout the 1960s. Thus, in the late 1960s-early 1970s, England had a large Jamaican community. Most of Jamaican migrants lived in working-class districts such as Tottenham (North London) and Brixton (South London), the latter having probably the largest concentration of Jamaican immigrants in the UK. It was basically in that context that the Jamaican popular music of the time, ska, rocksteady and early reggae, gained followers within the Jamaican expatriate communities through the sound system subculture 1 . In the meantime, a youth counterculture movement was surfacing in the same London working-class districts: the skinheads.

- 2 The term “dancehall” refers to the space in which popular Jamaican recordings were aired by local s (...)

3 Actually, the skinhead movement evolved from the modernist movement, a counterculture youth movement which originated in London in the late 1950s but whose peak corresponds to the mid-1960s. Modernists (often simply called “mods”) were usually from working-class backgrounds. They used to cut their hair close, both to help their fashion and prevent their hair from impeding them in street fights. They used to meet every Saturday to attend football matches and support their local teams, which often ended in massive fights between opposing supporters. They were tough kids for sure but paradoxically they “affected dandyism” (Moore 1993: 24). At night, for example, mods used to dress in their finest clothes and go to Black night clubs to dance to Afro-American music like rhythm and blues and soul music which they were absolutely fond of. They also often went to dancehall 2 so as to dance to new sounds brought by Jamaican immigrants such as ska, rocksteady and early reggae. At these gatherings, mods and Jamaican rude boys danced, laughed and drank together, sharing their taste for these musical genres. It is worth underlining that the rude boy movement erupted in the early 1960s as a distinct force among the unemployed young males of Kingston. Jamaican musicologist Garth White said that these young males “became increasingly disenchanted and alienated from a system which seemed to offer no relief from suffering. Many of the young became rude . ‘Rude boy’ (bwoy) applied to anyone against the system” (White 1967: 40-41). Thus, mods and rude boys merged together giving rise to the skinhead movement. In an interview that I conducted with Roddy Moreno, leader of The Oppressed and an emblematic figure of the skinhead movement, the latter said:

3 Roddy Moreno, interview conducted by myself on 29 September 2008.

4 “As much of Britain kept itself distant from the immigrants the skinheads embraced Jamaican style and music. We would attend all night Blues parties together and many young Blacks were skinheads themselves. Remember the [Jamaican] migrants were relatively poor and so the working class kids had more in common with them than with the middle and upper classes of Britain. We lived on the same streets, went to the same schools and we partied together. While much of Britain saw the migrants as ‘those black people,’ we skinheads saw them as ‘our black mates.’ Of course there were skinheads with racist attitudes, but most skinheads had black mates and most skinhead gangs had black kids amongst their ranks. […] Skinhead would not exist without Jamaica” 3 .

5 At that time, as Roddy Moreno explained, most skinheads were close to Jamaican youth, Jamaican rude boys in particular, whom they had things in common with. Indeed, they lived in the same poor London areas, they were bound by their country history, and they were united by the same spirit of rebellion and a mutual love of football, street fights, clothing, music, drugs (above all marijuana called ganja in Jamaican Patois) and so on. From a musical point of view, Jamaican artists like Prince Buster, Lauren Aitken, Max Romeo, Desmond Dekker and The Hot Red All Stars, among others, met great success within the skinhead movement. Skinheads recognized themselves within their rebel lyrics praising rude boys such as Desmond Dekker’s “Shanty Town”:

“Dem a loot, dem a shoot, dem a wail A Shanty Town Dem rude boys out on probation A Shanty Town Dem a rude boy when dem come up to town A Shanty Town” (Desmond Dekker 1966).

- 4 Tony Harcup, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Journalism Studies at the University of Sheffield (...)

6 Some of the above-mentioned artists even dedicated some of their songs to this faithful audience. Lauren Aitken’s “Skinhead Train” (1969) and The Hot Red All Stars’s “Skinhead Don’t Fear” (1970) clearly illustrate this fact. But, by the mid 1970s, the British National Front (BNF) started recruiting skinheads as street soldiers since they were known for their violence and there was an ideal breeding ground for racism. Indeed, Roddy Moreno emphasized in the interview that “there were skinheads with racist attitudes.” In addition, it is said that assaults on Asians (“Paki-bashing”) and homosexuals (“fag-bashing”) were common forms of skinhead brutality 4 . It was at that stage that racism infiltrated into the skinhead movement. Mark Downie, an ex-skinhead and leader of the English ska band N°1 Station, said regarding that phenomenon:

5 Mark Downie, interview conducted by myself on 30 September 2008.

7 “By 1975, skinheads had grown up and moved on to different things, and the upsurge of far-right politics in the form of the National Front was actively leafleting the football terraces, targeting past and present skinheads, and effectively hijacking the fashion” 5 .

6 For further information on the skinhead movement, see George Marshall 1991.

8 The influence of the BNF led to a split within the movement becoming divided between traditional skinheads, namely non-racist ones who remained faithful to Jamaican music, and Neo-Nazi skinheads (called boneheads by traditional skinheads) who turned to a sort of violent punk music. However, despite this regrettable divide, the traditional skinhead movement has perpetuated itself, giving rise to similar branches throughout the world, especially in Europe and the USA 6 .

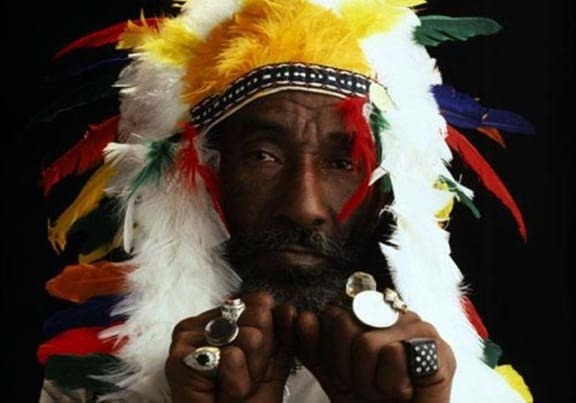

Photo 1. Jamaican ska singer Prince Buster surrounded by Spanish skinheads

Source: Henrique Simoes, April 2004

10 Reggae music not only influenced the skinhead movement, but it also strongly influenced the punk movement, partly thanks to Don Letts, a young black man born in London of Jamaican parents. In 1977, Don Letts was a DJ at the legendary nightclub The Roxy where he introduced reggae and dub to the burgeoning punk rock scene, thereby influencing British punk bands like The Clash and The Sex Pistols. In an interview that I conducted with Don Letts, he explained to me how he happened to play reggae in this famous punk-oriented club:

7 Don Letts, interview conducted by myself on 24 March 2009.

11 “This was so early in the punk movement that there weren’t any punk record to play. So I played what I loved, dub reggae, and lucky for me the punks loved it too, although I did slip in a bit of New York Dolls, Iggy and the Stooges and the MC5 occasionally. They liked the bass lines and the anti-Establishment stance and the fact that the songs were about something (and they didn’t mind the weed either!)” 7 . The same year, The Clash started mixing punk and reggae rhythms together and they covered Junior Murvin’s reggae hit “Police And Thieves.” As for Bob Marley, whom was actually Don Letts’ friend and moreover had been introduced to the punk scene by the latter, he released “Punky Reggae Party,” a tune that became the anthem to the cultural exchange that Don Letts had created at the Roxy. Another song that deserves to be quoted is The Clash’s “The Guns Of Brixton” which evokes police repression in Brixton and echoes the subsequent riots in 1981:

“When they kick out your front door How you gonna come? With your hands on your head Or on the trigger of your gun When the law break in How you gonna go? Shot down on the pavement Or waiting in death row You can crush us You can bruise us But you’ll have to answer to Oh, Guns of Brixton” (The Clash 1979).

- 8 For further information on the links between the punk and reggae movements in the UK during the 197 (...)

12 This song clearly represents the anger of the people against a society which makes them live in misery, the police incarnating this society. Actually, punk rock and reggae music, though completely different from a musical perspective, shared some similarities, to begin with the fact that they both were counterculture musical movements, spreading a message of rebellion against the Establishment. In other words, punks and Rastas shared a same idea of freedom and of rebellion against social norms and the setting of these norms 8 . Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, numerous other British pop and rock artists were inspired by reggae and paid tribute to it, among which: The Rolling Stones; Eric Clapton –– in 1974, he cut Bob Marley’s “I Shot The Sheriff” which was a true hit ––; Nina Hagen, who is German by birth but made a career in Britain; The Police led by Sting –– “Roxanne” was a worldwide hit in 1978 ––; Culture Club led by Boy George and so forth.

13 Most recently, reggae, dub and dancehall have also greatly influenced the British electronic musical scene which finds its roots in the remix technique quasi-intrinsic to Jamaican music since the emergence of dub in the late 1960s (Veal 2007: 2). It gave rise to new musical genres such as drum and bass, jungle and trip-hop, the latter being pioneered by artists like Massive Attack, Portishead or Tricky. The three of them are originating from Bristol (South West, England). Besides remix, the sound system subculture has also greatly impacted on the British electronic musical scene, resulting in the rave or free parties, namely events held outdoors or in disused buildings. Spiral Tribe, a group of artists originating from London were among the first to organize this type of unlicensed parties in the UK in the early 1990s. It is worth adding that dreadlocks and ganja which belong to the world of ravers also seem to result from the Jamaican reggae universe. Last but not least, Jamaican reggae has obviously fathered British reggae whose emblematic figures remain Steel Pulse, Aswad, UB 40, Maxi Priest and Bitty McLean among others. Such musical and social phenomena are not exclusively linked with the UK, but they have spread throughout Europe. France, for instance, is another European country which has been greatly influenced by reggae both musically and culturally.

1.2. The French Case

14 In the late 1970s, lured by the rebellious aspect of reggae, pop singers like Bernard Lavilliers and Serge Gainsbourg were among the first white French artists to record reggae rhythms. In the meantime, numerous young people of African and French Caribbean origins recognized themselves in the socio-politico-spiritual message conveyed by Jamaican reggae music, which gave birth to a French reggae school pioneered by artists like Pablo Master, Princess Erika, Daddy Yod, General Murphy, Daddy Nuttea or Tonton David. The previous mentioned artists remained on top until the mid-1990s when they got overshadowed by a new wave of reggae artists mostly composed of white singers such like Pierpoljak, Sinsemilia, Tryo, Baobab and Mister Gang among others. However, since the early 21 st century, a new generation of reggae/ dancehall artists has emerged headed by people mainly coming from the French West Indies. Among the latter, it is important to mention singers like Lord Kossity, Mr. Janik, Raggasonic and more recently Admiral T, Straika D and Yaniss Odua.

- 9 The May 1968 events started with huge demonstrations in French industry and among students, and cul (...)

- 10 The 2005 civil unrest consisted of a series of riots and violent clashes, involving mainly the burn (...)

15 To understand the importance of reggae in the French popular culture, two major facts must be taken into account. The first one is the old tradition of French rebellious thought characterized among other things by the French revolution of 1789, the widespread unrest of May 1968 9 , the civil turmoil of October and November 2005 10 and the long tradition of left-wing intellectuals and artists such as Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Boris Vian, Jacques Brel, Léo Ferré, Georges Brassens, Barbara and Juliette Gréco. This must certainly be one of the reasons why numerous white people like and/ or play reggae in France. The second fact is that France is a former colonial power, which has played a direct role in the fact that French society is clearly a multicultural and multiethnic one. Consequently, many immigrants and young people of African and West Indian origins have been recognizing themselves in this musical style denouncing slavery, colonialism, exclusion and oppression. Reggae lyrics’ spirituality has also attracted them, all the more so since Rastafari is a Pan-African religion. Indeed, Blacks are generally spiritual and mystic people. Kenyan-born philosopher John Mbiti emphasizes this point in his Concepts of God in Africa stating that “African people do not know how to exist without religion” (Mbiti 1998: 95). Finally, the Jamaican-African reggae rhythm does appeal to these people of African and Caribbean descents. The following excerpts will give the reader a general idea of what French reggae is:

“Issus d’un peuple qui a beaucoup souffert Nous sommes issus d’un peuple qui ne veut plus souffrir Dédicacé par Mosiah Garvey Autour d’un drapeau il faut se rassembler Le rouge pour le sang que l’oppresseur a fait couler Le vert pour l’Afrique et ses forêts Le Jaune pour tout l’or qu’ils nous ont volé Noir parce qu’on n’est pas blanc, on est tous un peu plus foncé Symbole d’unité africaine de solidarité Noir et ensemble faut danser, Tonton reviens DJ…” (Tonton David 1990)

“Originating from a people who has suffered a lot We come from a people who no longer wants to suffer Dedicated by Mosiah Garve y Around a flag we must rally Red for bloodshed made by oppressors Green for Africa and its forests Yellow for all the gold they have stolen from us Black because we’re not White, we’re all a bit darker Symbol of African unity of solidarity Black and together we must dance, Tonton is back as a DJ…” (my own translation);

“Tes yeux sont bleus ta peau est blanche tes lèvres sont rouges Qu’est-ce que je vois au lointain ? C’est un drapeau qui bouge Peux tu me dire ce qui se passe ? Qui représente une menace ? Est-ce toi qui ne veux pas perdre la face ? […] On dit tout haut ce que les jeunes des ghettos pensent tout bas Les fachos éliminent les Rebeus les Renois C’est vrai, certains me diront que c’est une banalité Mais en attendant beaucoup de nos frères se font tuer Tes yeux sont bleus ta peau est blanche tes lèvres sont rouges Si je vois un facho devant moi obligé faut qu’il bouge Je me sers de mon micro comme je me servirais d’un uzi Pour éliminer le FN, Le Pen et tous les fachos à Paris…” (Raggasonic 1995)

“Your eyes are blue, your skin is white, your lips are red What I see looming on the horizon? This is a moving flag Can you tel l me what’s happening? Who represents a threat? Is it you who doesn’t want to lose face? […] We say out loud what ghetto youths are all thinking Fascists eliminate Arabs and Blacks To tell the truth, some people will tell me it’s a banality But by the meantime, many of our brothers are being killed Your eyes are blue, your skin is white, your lips are red If I see a fascist before me, he is forced to move I use my mike as I’d use a Uzi To eliminate the FN, Le Pen and all fascists in Paris…” (my own translation);

“Moi j’sais pas jouer Aut’chose que du reggae J’sais pas danser J’remue que sur du reggae En politique c’est facile il suffit d ’être habile Pour emmener brouter les bœufs Mais j’suis pas le genre de bison qui aime les bâtons Les barbelés pour horizon Ils disent monsieur Pekah tu as une jolie voix Mais pourquoi t’entêter comme ça Prends plutôt une gratte sèche Laisse-toi pousser la mèche Et ta côte va monter en flèche Oh oh oh Bla bla bla…” (Pierpoljak 1998)

“The only thing I can play Is reggae I can’t dance I only jive on reggae In politics it’s easy, you just need to be skilful To take the oxen to the grazing field But I’m not the type of beasts that like canes Barbed wire as horizon They say Mr. Pekah you have a nice voice But why do you in that way You’d rather take an acoustic guitar Grow a stray lock And you will rocket to fame Oh oh oh blah blah blah” (my own translation).

16 Tonton David’s song is clearly a militant song dealing with Black history. It denounces slavery, African unity and solidarity as well as Black pride. This tune is obviously built in the purest Rasta tradition. Raggasonic’s incisive lyrics are against racism and French extreme right-wing embodied by the FN and its long-term leader Jean-Marie Le Pen. They also implicitly defend the multicultural and multiethnic aspects of French society. As for Pierpoljak’s “Je sais pas jouer,” it rebels against the conventional society which, according to the singer, indoctrinates people with false social beliefs and tends to recommend for white artists like him to embrace pop-rock career and certainly not a reggae career reserved for Blacks. Pierpoljak’s song is a hymn to freedom finding its origins in the old tradition of French rebellious thought mentioned earlier. So for almost three decades, reggae and dancehall, just like rap, rock and techno music, have been part of the French musical universe and numerous French people, from various backgrounds and origins, have embraced the Rasta lifestyle and ideology.

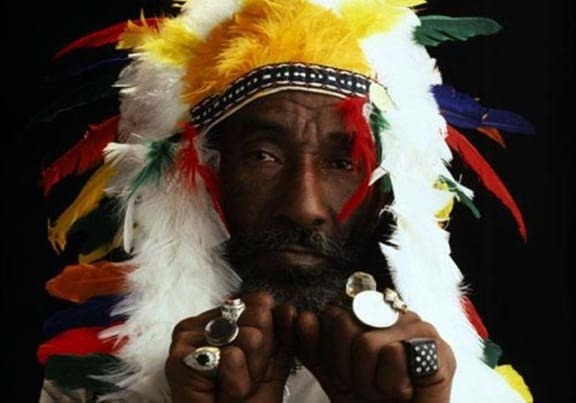

Photo 2. Daddy Mory, founder member of Raggasonic

Source: Jérémie Kroubo Dagnini, April 2008

- 11 See Giulia Bonacci, “De la diffusion musicale à la transmission religieuse : reggae et rastafari en (...)

- 12 German reggae/ dancehall DJ Tilmann Otto, better known by his stage name Gentleman, is today one of (...)

17 Similar ethno-musical phenomena have been taking place, more or less importantly, in the rest of Europe such as in Italy 11 or Germany 12 , as well as in the USA and Africa.

2. The Impact of Reggae Music on the USA

18 The major impact that reggae music has had on the USA concerns rap music. Indeed, in the 1950s and 1960s, like the UK, the USA welcomed hundreds of thousands of Jamaican migrants, many of whom settling in the South Bronx in New York. These migrants remained in contact with Jamaica through regular trips to their homeland and never lost touch with the cultural evolution that took place on the island. Thus, when in the late 1960s-early 1970s, toasting also known as DJ style became in vogue in Jamaica, pioneered by artists like U Roy or Big Youth, this new genre deriving from reggae rapidly reached New York. This Jamaican DJ culture coupled with American urban “ingredients” gave rise to rap music and the hip-hop culture in the 1970s. Jamaican-born DJ Kool Herc, who moved to the Bronx, New York, in 1967, was instrumental in originating rap music and hip-hop culture (Chang 2005: 67-85). In the following decades, numerous American rappers of Jamaican background became famous such as Notorious B.I.G., Busta Rhymes or Heavy D among others.

19 The cultural relationship between hip-hop and reggae cultures implies the existence of common points between these two universes. Firstly, they both emerged from a context of oppression and both reflect the lifestyle and sensibilities of black inhabitants of urban ghettos. Secondly, both cultures rebel against the Establishment. Indeed, Afrika Bambaataa and Public Enemy’s rap as well as Big Youth’s toasting and Burning Spear’s reggae have been denouncing for decades social injustices faced by Blacks respectively in the USA and in Jamaica. In addition, these committed artists fight against Eurocentrism and advocate in their own way Pan-Africanism.

3. The Impact of Reggae Music on Africa

20 The Jamaican population is primarily of African descent, reggae has its roots in ancient African musical forms and since its appearance reggae singers have constantly paid tribute to the motherland Africa. Not surprisingly, reggae has had a strong impact on the African continent. Actually, it is the charismatic and powerful Bob Marley who first hit the continent by the end of the 1970s with tunes like “Africa Unite” (1979) or “Zimbabwe” (1979). He rapidly became a symbol for African youth and many started identifying with Jamaicans and the Rasta culture. Indeed, it was easy for young Africans to compare themselves with Jamaicans for they were both black people living in harsh conditions –– for instance, Jamaican ghettos are rather similar to African ones ––, and above all they were both oppressed by white people from a political, financial and social perspective. Consequently, numerous Africans started playing reggae and eminent artists emerged such as Alpha Blondy –– who is considered by some critics as one of the greatest reggae singers in the world –– and Tiken Jah Fakoly in Cote d’Ivoire or the late Lucky Dube in South Africa.

3.1. The Ivorian Case

13 For further information on the role of France in the Ivorian crisis, see Kroubo Dagnini 2008a: 117.

21 Before moving on the impact of reggae on Cote d’Ivoire, let’s have a quick look at the history of this West African country. It will help us to better understand the overall situation. Cote d’Ivoire borders the countries of Liberia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso and Ghana. The most ancient and principal populations include the Kru, originating from Liberia, the Senoufo, coming from Burkina Faso and Mali, the Mandika (also known as Mandigo or Malinke), coming from Guinea, and the Akan (Agni, Baoulé), originating from Ghana. France took an interest in Cote d’Ivoire in the 1830s-1840s, enticing local chiefs to grant French commercial traders a monopoly along the coast. France’s main goal was to stimulate the production of exports. Coffee, cocoa and pal oil crops were soon planted along the coast and a forced-labour system became the backbone of the economy. In 1893, Cote d’Ivoire was made a French colony after a long war against the Mandika forces led by warlord Samory Touré and the Baoulé people. In 1958, Cote d’Ivoire became an autonomous republic before being given full independence in 1960, headed by Félix Houphouët-Boigny, General de Gaulle’s loyal servant. During his 33-year time in power, Félix Houphouët-Boigny openly favoured his ethnic group (Baoulé) and allowed France to exploit and plunder the mineral resources of his country (coffee, cocoa, hevea, banana, cotton). In return, French Presidents de Gaulle, Pompidou, Giscard d’Estaing and Mitterrand assured him a peaceful reign and turned a blind eye to the fortune he built to the detriment of the Ivorian people. Theses ambiguous, close and opaque relationships that the former Ivorian President had with France inspired François-Xavier Verschave, co-founder of Survie association, who popularized the expression Françafrique . Françafrique (“FrancAfrica”) is a term that ironically refers to the expression used in 1955 by Félix Houphouët-Boigny to describe the “good” relationships between France and Africa. It is a secret criminal club composed of economic, political ad military actors, operating both in France and Africa, organized in lobbies and networks, and centred on the misappropriation of two revenues: raw materials and the ‘Public Aid for Development’ (APD). […] This system is naturally hostile to democracy. The term also refers to confusion, a domestic familiarity looking towards liberties: presidents’ offspring, ministers and generals all take part in trafficking” (Agir ici/ Survie 1996: 8-9; my own translation). The expression also means France à fric , François-Xavier Verschave emphasizing that over the course of four decades, hundreds of billions of euros misappropriated from debt, aid, oil, cocoa…or drained through French importing monopolies have financed French political-business networks –– all of them offshoots of the main neo-Gaullist network ––, shareholders’ dividends, the secret services’ major operations and mercenary expeditions (Diop, Tobner and Verschave 2005: 106-107; my own translation). Houphouët-Boigny ruled with an iron hand until his death in 1993 and was succeeded by a Baoulé of his choice, Henri Konan Bédié, who led the same “FrancAfrican” politics until December 24 th , 1999, the date at which he was overthrown by General Robert Guéï (a member of the Yacouba ethnic group originating from Liberia). A presidential election was held in October 2000 in which Guéï vied with Laurent Gbagbo (a member of the Bété ethnic group originating from Liberia). The latter, Houphouët Boigny’s historic opponent, won the election. It is worth noting that Henri Konan Bédié, accused of embezzlement, and former Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara, whose nationality was questioned, were disqualified from running. Some people saw it as the fruit of a political arrangement between Laurent Gbagbo and Robert Guéï. However, on 26 October 2000, socialist Laurent Gbagbo, Houphouët Boigny’s historic political opponent and therefore France’s most hostile political opponent too, became the fourth president of the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire. On 19 September 2002, only two years after his coming to power, rebels allegedly coming from the north of the country tried to overthrow him but they failed. Nevertheless, they managed to control several strategic cities located in the middle and the north of the country. Since then, despite the French and UN interventions, Cote d’Ivoire has been divided between the pro-government party South (composed mainly of Christians) and the North (composed mainly of Muslims) , held by rebels. As a result, Cote d’Ivoire would suffer from an ethnic and possible religious conflict. Obviously some ethnic tensions are palpable in this country, all the more so since they have been exacerbated by politicians from all sides for decades. Yet, it would seem that economic elements also played a great part in sparking off the crisis. Indeed, it would seem that France itself, which did not want to lose its Ivorian pré-carré with Laurent Gbagbo’s unexpected coming to power, launched the conflict. This is all the more probable since, a short time before the 2002 coup attempt, Laurent Gbagbo was about to challenge French multinationals’ financial interests in Cote d’Ivoire, considering the recourse to international invitations to tender. It is worth keeping in mind that multinationals such as Bouygues and Bolloré, among others, have been controlling every aspects of national life –– transport, water and electricity. Another crucial fact to be mentioned in this crisis is that large oil, gas and gold fields were discovered in and offshore the country, natural resources which are likely to reinforce French interest in Cote d’Ivoire and consequently which are likely to give them the idea of orchestrating a coup 13 .

22 Thus, like most African countries, Cote d’Ivoire’s history has been associated with colonialism, neo-colonialism, tribalism, political manoeuvres, tyrannies, corruption, and the plundering of natural resources by the former colonial power. So, like Jamaica, Cote d’Ivoire has been a favorable place for the explosion and development of reggae which has become the principal medium to point the finger at the scourges previously mentioned. Such plagues are denounced by Alpha Blondy and Tiken Jah Fakoly who are the indisputable ambassadors of reggae in Cote d’Ivoire and the genuine spearheads of reggae in Africa. Alpha Blondy’s “Bloodshed in Africa” (1986) and Tiken Jah Fakoly’s “Françafrique” (2002) give an insight of what African reggae is. The first song denounces the bloody neocolonial policy developed by Western countries in Africa:

“Bloodshed in Africa Bloodshed in Africa What a shame, what a shame

It’s a bloody shame oh yeah! It’s a mighty shame oh Lord! See Babylonians are coming around and messing around…” (Alpha Blondy 1986).

23 As for Tiken Jah Fakoly’s song, it accuses France and America of being at the origin of poverty and conflicts in most African countries, encouraging arms trafficking and looting African natural resources:

“Réveillez-vous! La politique France Africa C’est du blaguer tuer Blaguer tuer La politique Amérique Africa C’est du blaguer tuer Blaguer tuer

Ils nous vendent des armes Pendant que nous nous battons Ils pillent nos richesses Et se disent être surpris de voir l’Afrique toujours en guerre Ils ont brûlé le Congo Enflammé l’Angola Ils ont brûlé Kinshasa Ils ont Brûlé le Rwanda…” (Tiken Jah Fakoly 2002)

“Wake up! Politics France Africa That’s bullshit Bullshit Politics America Africa That’s bullshit Bullshit

They sell us weapons While we’re fighting They steal our natural resources And claim being astonished to see Africa always at war They have burned down Congo Set fire to Angola They have burned down Kinshasa They have burned Rwanda…” (my own translation).

24 Alpha Blondy and Tiken Jah Fakoly are therefore among the greatest reggae singers in Africa, if not in the world. In Cote d’Ivoire, most reggae singers model themselves upon them, including Ismaël Isaac, Ras Goody Brown, Pablo Uwa, Naphtaline, Kajeem and Beta Simon just to name a few, and reggae pulse has become the heartbeat of the country. Cote d’Ivoire really positions itself among the major reggae countries in the world. Like the French case, the growth of reggae in Cote d’Ivoire has been accompanied by significant social impacts.

25 The most striking social impact of reggae on Cote d’Ivoire is without a doubt the fact that reggae is everywhere: live and recorded, in the country and the city, at home, in bars, in taxis etc. Ex-Wailer Tyrone Downie, who produced Tiken Jah Fakoly’s françafrique album, was really and agreeably surprised the first time he went to Cote d’Ivoire:

14 Tyrone Downie, interview conducted by myself on 8 February 2008.

26 “The first time I went to Abidjan, I was astonished by the fact that all cafés played reggae, all bands played reggae, you could hear reggae everywhere, in taxis, at people’s houses, at dances, in the ghetto, EVERYWHERE! I said to myself, ‘I am in Africa or in Jamaica?’ Even in some traditional music you can hear reggae sounds. Then Tiken told me, ‘You know Tyrone, Cote d’Ivoire is the second reggae country in the world after Jamaica!” 14 .

15 Abdou Aziz Kane, interview conducted by myself on 28 December 2004.

27 Indeed, reggae is everywhere in Cote d’Ivoire, which has resulted in a “Rastafarization” of Ivorian society with more and more people wearing dreadlocks, wearing Ethiopian colours and smoking ganja, among other things, especially among poor urban youth. The Rasta culture is such a vital part of society in Cote d’Ivoire that a Rasta village was born a few years ago in the district of Vridi in Abidjan. This is a place where Rastas, reggae musicians, singers, painters and some other artists dealing with Rasta culture usually meet. Moreover, Alpha Blondy himself recorded the video clip of his song “Demain t’appartient” over there. Nevertheless, even if young people in Cote d’Ivoire have been identifying with Jamaican reggae music and Rasta culture, elders generally have a low opinion on these musical and cultural movements which they still associate with drugs and gangsterism. Furthermore, as mentally ill people commonly wear dreadlocks (simply because they never comb their hair), they usually consider dreadlocks a dirty and messy hairstyle, if not insanity. One could conclude this part quoting Dr Abdou Aziz Kane, a Rastafarian from Senegal living in France who sadly remarked: “Africans have apparently forgotten that wearing dreadlocks used to be part of an ancestral tradition in Africa. Check your history!” 15 .

Photo 3. Alpha Blondy performing in Paris

Source: Jérémie Kroubo Dagnini, May 2009

3.2. The South African Case

28 South Africa, with apartheid (officially abolished in 1991), is indisputably the African country which best symbolizes racial and social injustices mentioned earlier. In this extremely tense socio-political climate, a voice emerged to denounce such evils: Lucky Dube, Alpha Blondy and Tiken Jah Fakoly’s counterpart, the emblematic figure of South African reggae. Throughout his fertile career which he started in 1980, Lucky Dube never stopped denouncing discrimination, segregation and exclusion, which black South Africans were the victims of. He also advocated unity among people. Among his most representative albums, one must mention Slave , Prisoner and Victims . Lucky Dube was killed in October 2007, in the Johannesburg suburb where the criminality rate is, like Kingston’s, one of the highest in the world.

- 16 Shinichiro Suzuki, ““Samurai Looking to the West”: Japan and Its Others as (Un)sung in Japanese Reg (...)

- 17 Shuji Kamimoto, “Spirituality within Subculture: Rastafarianism in Japan,” paper presented on Sunda (...)

29 To conclude on the importance of reggae music in the worldwide cultural universe, it is essential to mention the influence of reggae in Latin America, especially in Brazil with the development of samba-reggae since the early 1980s as well as in Puerto Rico, Panama or Costa Rica with the success of reggaeton since the early 2000s. It is also crucial to emphasize the Pacific region. As Jennifer Raoult claims in her article entitled “La scène reggae de Nouvelle-Zélande” (“The Reggae Scene of New Zealand”), reggae and Rastafari are extremely popular in New Zealand as well as in New Caledonia and Australia, especially among the native people. Indeed, like Jamaicans and Africans, Maori, Aborigines and Kanaks have experienced colonialism, enslavement, genocides and denial of their traditions and religious beliefs. So, many of them have been recognizing themselves through reggae songs’ lyrics and the Rastafari movement, which in a way help them to recover their rights and dignity. Last but not least, reggae music and Rastafari are getting rather popular in Asia too, in Japan in particular as showed the papers of Shinichiro Suzuki (Shinshu University) and Shuji Kamimoto (Kyoto University) presented during the 2008 ACS Crossroads Conference which took place at the University of the West Indies (UWI) in Mona, Jamaica, and respectively entitled ““Samurai Looking to the West”: Japan and Its Others as (Un)sung in Japanese Reggae” 16 and “Spirituality within Subculture: Rastafarianism in Japan.” 17 Noting that Bob Marley’s concerts in Japan, New Zealand and Australia in April 1979 are credited with being the genesis of reggae music and Rasta culture in these regions of the world.

30 In conclusion, the impact of reggae and Rastafari on the worldwide cultural universe is colossal. It is not an overstatement to say that almost the whole world have been culturally influenced by reggae music and its Rastafarian message. How can we explain such a scattering? It would seem that Jamaican large migrations as well as Bob Marley’s huge success have played a major role in spreading these fundamental elements of Jamaican culture throughout the world. Besides, foreigners appear to be captivated by reggae music because of its militant, rebellious and spiritual message as well as its positive and universal message dealing with the concept of unity. Rasta symbols such as dreadlocks, Ethiopian colours, ganja or military clothing also play an important part in charming foreign audience. In other respects, a final remark could be made: the great importance of reggae and Rastafari in the worldwide cultural universe raise the question of the place of reggae and Rastafari in Caribbean studies in France. Like rock, punk or hippie movements, reggae and Rastafari have influenced societies from a musical, cultural and political point of view. For that reason, they really can not be ignored, especially in the field of Caribbean Studies, which in France and the French West Indies, unfortunately, tend to focus on topics like tourism, migrations or environmental geography.

Bibliography

Agir ici/ Survie (1996). Dossier noir de la politique africaine de la France n°7. France-Cameroun, Croisement dangereux !, Paris, L’Harmattan.

Bonacci, G. (2003). « De la diffusion musicale à la transmission religieuse : reggae et rastafari en Italie » in G. Bonacci et S. Fila-Bakabadio (dir ), Musiques populaires. Usages sociaux et sentiments d’appartenance. Dossiers africains , Paris, EHESS, p.73-93.

Bradley, L. (2000). Bass Culture , Londres, Penguin Books.

Chang, J. (2005). Can’t Stop Won’t Stop , New York, Picador.

Chevannes, B. (1994). Rastafari Roots and Ideology , New York, Syracuse University Press.

Diop, B.B., O. Tobner et F-X. Verschave (2005). Négrophobie . Paris : Éditions les Arènes.

Kroubo, Dagnini J. (2008a). «Dictatures et protestantisme en Afrique noire depuis la décolonisation: le résultat d’une politique françafricaine, et d’une influence américaine certaine», Historia Actual Online , 17 : 113-128.

Kroubo Dagnini, J. (2008b). Les origines du reggae : retour aux sources. Mento, ska, rocksteady, early reggae , Paris, L’Harmattan.

Letts, D. (2008). Culture Clash: Dread Meets Punk Rockers , Londres, SAF Publishing.

Marshall, G . (1991). Spirit of ’69: A Skinhead Bible , Dunoon, S.T. Publishing.

Mbiti, J-S. (1970). Concepts of God in Africa , Londres, SPCK.

Moore, J-B. (1993). Skinheads Shaved for Battle , Bowling Green, OH, Popular Press.

Raoult J. (2006). «La Scène Reggae de Nouvelle Zélande». Reggae.fr. 20 Octobre 2006. URL : < http://www.reggae.fr/liste-articles/6_841_La-Scene-Reggae-de-Nouvelle-Zelande.html >, dernière consultation: 8 décembre 2008.

Salewicz, C. et A. Boot (2001). Reggae Explosion: histoire des musiques de Jamaïque , Paris, Éditions du Seuil.

Sherlock, P. and H. Bennett ( 199 8). The Story of the Jamaican People , Kingston, Ian Randle Publishers.

Veal, M-E. (2007). Dub: Soundscapes & Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae , Middletown, Wesleyan University Press.

White, G. (1967). “Rudie, Oh Rudie”. Caribbean Quarterly , 13(3) : 39-45.

Discographie

Aitken, Laurel (1969). “Skinhead Train” (Laurel Aitken). Londres, Nu Beat, NB 047-A, 45 tours.

Blondy, Alpha and The Wailers (1986). “Bloodshed in Africa” (Alpha Blondy). Blondy, Alpha and The Wailers. 1986. Jerusalem. Paris: Pathé Marconi EMI, 7464642, CD, chanson n°1.

Blondy, Alpha (2007). « Demain t’appartient » (Alpha Blondy et Lester Bilal). Blondy, Alpha,. 2007, Jah Victory, Paris: Mediacom, MED 0307, CD, chanson n°5.

Clapton, Eric (1974). “I Shot The Sheriff” (Bob Marley). New York: RSO Records, 2090 132-A, 45 tours.

Clash, The (1977). “Police and Thieves” (Junior Murvin et Lee Perry). Clash, The. 1977. The Clash. Londres: CBS Records, CBS 82 000, 33 tours, face B, chanson n°4.

Clash, The (1979). “The Guns Of Brixton” (Paul Simonon). Clash, The. 1979. London Calling. New York: CBS, 460114 4, cassette, face A, chanson n°10.

David, Tonton (1990). « Peuples du monde » (David Grammont et j. Boudhouallal). Paris: Virgin, 90621, 45 tours.

Dekker, Desmond (1966). “Shanty Town” (Desmond Dekker). Kingston: Beverley’s, WIRL LK 1687-1, 45 tours.

Dube, L. (1989). Slave. Newton: Shanachie Records, SH 43060, CD.

Dube, L. (1990). Prisoner. Newton: Shanachie Records, SH 43073, CD.

Dube, L. (1993). Victims. Newton: Shanachie Records, SH 45008, CD.

Hot Red All Stars, The (1970). “Skinhead Don’t Fear”. Londres: Torpedo, TOR 05-A, 45 tours.

Marley, B. and The Wailers (1977). “Punky Reggae Party” (Bob Marley et Lee Perry). Londres: Island Records, WIP 6410-B, 45 tours.

Marley, B. and The Wailers (1979). “Africa Unite” (Bob Marley). Londres: Island Records, WIP 6597-A, 45 tours.

Marley, Bob and The Wailers (1979). “Zimbabwe” (Bob Marley). Londres: Island Records, WIP 6597-A, 45 tours.

Pierpoljak (1998). « Je sais pas jouer » (Pierpoljak). Pierpoljak. 1998. Kingston Karma. Paris: Barclay, 559 206-2, CD, chanson n°1.

Police, The (1978). “Roxanne” (Sting). Londres: A&M Records, AMS 7348-A, 45 tours.

Raggasonic (1995). « Bleu, Blanc, Rouge » (Big Red et Daddy Mory). Raggasonic. 1995. Raggasonic. Paris: Source Records, 7243 8 40934 2 6, CD, chanson n°10.

Tiken Jah Fakoly (2002). « Françafrique» (Tiken Jah Fakoly) . Tiken Jah Fakoly . 2002 . F rançafrique, Paris: Barclay, 589613-2, CD, chanson n°1.

1 Sound systems emerged in the late 1940s in Kingston’s ghettos. This subculture appeared for precise reasons. First, at the time, only the white and brown elite had access to theatres and clubs. Similarly, radio was not within the reach of everyone. Last but not least, both clubs and radio played folk mento songs and jazz, but certainly not rhythm and blues which was in vogue among youth during the decade of the 1950s. So, the black ghetto youth turned to dancehall , accessible to everyone, where censorship did not exist and where music was definitely rousing. It is worth pointing out that major Jamaican musical genres such as ska, rocksteady and reggae were largely popularized by sound systems. This subculture was brought along to the UK by Jamaican immigrants. For further details, see Kroubo Dagnini 2008b: 104-119.

2 The term “dancehall” refers to the space in which popular Jamaican recordings were aired by local sound systems.

4 Tony Harcup, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Journalism Studies at the University of Sheffield, interview conducted by myself on 26 October 2008.

8 For further information on the links between the punk and reggae movements in the UK during the 1970s, see Don Letts 2008.

9 The May 1968 events started with huge demonstrations in French industry and among students, and culminated in a general strike which was perceived both as a challenge to the Establishment and a cry for freedom.

10 The 2005 civil unrest consisted of a series of riots and violent clashes, involving mainly the burning of cars and public buildings. This wave of violence was triggered by the accidental death of two teenagers, Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré, in Clichy-sous-Bois, a working-class commune in the Eastern suburbs of Paris. They were chased by the police – though they were guilty of nothing but “being of foreign origins” – and tried to hide in a power substation where they were electrocuted.

11 See Giulia Bonacci, “De la diffusion musicale à la transmission religieuse : reggae et rastafari en Italie,” in Giulia Bonacci et S. Fila-Bakabadio, (dirs.), 2003, Musiques populaires. Usages sociaux et sentiments d’appartenance. Dossiers africains , Paris, EHESS, 73-93.

12 German reggae/ dancehall DJ Tilmann Otto, better known by his stage name Gentleman, is today one of the most popular reggae artists in the world.

16 Shinichiro Suzuki, ““Samurai Looking to the West”: Japan and Its Others as (Un)sung in Japanese Reggae,” paper presented on Sunday 6 July 2008 at UWI, Mona, Jamaica, during the 2008 ACS Crossroads Conference.

17 Shuji Kamimoto, “Spirituality within Subculture: Rastafarianism in Japan,” paper presented on Sunday 6 July 2008 at UWI, Mona, Jamaica, during the 2008 ACS Crossroads Conference.

List of illustrations

Electronic reference.

Jérémie Kroubo Dagnini , “ The Importance of Reggae Music in the Worldwide Cultural Universe ” , Études caribéennes [Online], 16 | Août 2010, Online since 15 August 2010 , connection on 01 November 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudescaribeennes/4740; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/etudescaribeennes.4740

About the author

Jérémie kroubo dagnini.

Université des Antilles et de la Guyane ; ATER ; [email protected]

The text only may be used under licence CC BY-NC 4.0 . All other elements (illustrations, imported files) are “All rights reserved”, unless otherwise stated.

- Geographical index

Call for papers

- Current Calls

- Closed Calls

Abstracting and Indexing

- Abstracting-Indexing

Full text issues

- 57-58 | Avril-Août 2024 Tourism, Security and Multidimensional Violence in Latin America

- 56 | décembre 2023 Haiti's dilemma: from crisis to crisis? (Part 2)

- 55 | Août 2023 The Maritimization: Diverse Perspectives

- 54 | Avril 2023 Cuba and the United States: the Genesis of a Conflictual Relationship

- 53 | Décembre 2022 Ressources marines et gestion des littoraux

- 52 | Août 2022 Haiti's dilemma: from crisis to crisis?

- 51 | Avril 2022 Technologies and Smart Tourist Destinations: between Rhetoric and Experimentation

- 50 | Décembre 2021 Anthropology of the Experience of Childbirth Around the World

- 49 | Août 2021 The Caribbean against the Covid-19: A Global Crisis and Local Solutions

- 48 | Avril 2021 Coastal planning - Haitian chronicles

- 47 | Décembre 2020 Cruise Tourism: Challenges and Prospects

- 45-46 | Avril-Août 2020 Haitian studies

- 43-44 | Août-Décembre 2019 The Caribbean Economy

- 42 | Avril 2019 The Caribbean faces an Emerging International Order

- 41 | Décembre 2018 Biodiversity and Management of Spaces and Natural Ressources

- 39-40 | Avril-Août 2018 The Caribbean City, the Cities in the Caribbean

- 37-38 | Août-Décembre 2017 Tourism, travels, Utopias

- 36 | Avril 2017 Yachting : Tourism Development vs Coastal Protection?

- 35 | Décembre 2016 Entrepreneuriat : Quelle voie pour le développement d'Haïti?

- 33-34 | Avril-Août 2016 Tourism and Natural Resources

- 31-32 | Août-Décembre 2015 Mass Tourism vs. Alternative Tourism

- 30 | Avril 2015 Luxury in all its States: Foundations, Dynamic and Plurality

- 29 | Décembre 2014 Social Movements, Here and There; from the Past and the Present

- 27-28 | Avril-Août 2014 Island Worlds: Spaces, Temporalities, Resources

- 26 | Décembre 2013 Marine Resources and Coastal Development: Vulnerability, Management and Adaptation to Global Change

- 24-25 | Avril-Août 2013 Tourism and Fight against Poverty: Theoretical Approach and Case Studies

- 23 | Décembre 2012 Insularity and Tourism: Territorial Project Matter

- 22 | Août 2012 Globalization: different faces, different perspectives

- 21 | Avril 2012 The Caribbean coast of Central America: fragmentation or regional integration

- 20 | Décembre 2011 Tourism, culture(s) and Territorial Attractiveness

- 19 | Août 2011 The changing world of coastal, island and tropical tourism

- 18 | Avril 2011 Cruise Tourism: Territorialisation, Construction and Development Issues

- 17 | Décembre 2010 Islands in crisis: Haiti, Jamaica, France's overseas

- 16 | Août 2010 Protean Diaspora

- 15 | Avril 2010 Marine Resources: Current Situations, Usages and Management

- 13-14 | Août-Décembre 2009 Tourism in Latin America: Development Challenges and Perspectives

- 12 | Avril 2009 Spaces and Protected Areas: Integrative Management and Participatory governance

- 11 | Décembre 2008 Small Island Territories and Sustainable Development

- 9-10 | Avril-Août 2008 Tourism in the Tropical and Subtropical Islands and Coastlines: Places Usages and Development Issues

- 8 | Décembre 2007 Migrations, Mobilities and Caribbean Identical Constructions

- 7 | Août 2007 The Major Natural Risks in the Caribbean

- 6 | Avril 2007 Ecotourism in the Caribbean

- 5 | Décembre 2006 Micro-Insularity and Marine Environments Degradation: Example of the Caribbean

- 4 | Juillet 2006

- 3 | Décembre 2005

Conference Proceedings

- 12 | Avril 2024 The development of overseas through the prism of its institutional status and specific economic and geographical features

- 11 | Novembre 2023 Jacques Stephen Alexis Awakenings, Exiles, Echoes

- 10 | Octobre 2023 Language and Society: Creole in the French West Indies From the 17th to the 19th Century

- 9 | Septembre 2023 Tourism, Crisis and Innovation

- 8 | décembre 2021 René Maran

- 7 | Juillet 2021 Regards sur Cuba

- 6 | Décembre 2020 Tourisme et environnement en Afrique

- 5 | Avril 2020 Cartographies et topologies identitaires

- 4 | Décembre 2019 Empreintes de l'esclavage dans la Caraïbe

- 3 | mars 2019 Écriture hors-pair d'André et de Simone Schwarz-Bart

- 2 | Novembre 2018 Risques, résilience et pérennité des destinations touristiques

- 1 | Juillet 2018 Patrimoines naturels, socio-économiques et culturels des territoires insulaires : quel avenir ?

Presentation

- Guidelines for Authors

- Publication Ethics and Malpractice Statement

- Copyright Transfer Agreement

Informations

- Mentions légales & crédits

- Politique de dépôt en archives ouvertes

- Publishing policies

Newsletters

- OpenEdition Newsletter

In collaboration with

Electronic ISSN 1961-859X

Read detailed presentation

Site map – Syndication

Privacy Policy – About Cookies – Report a problem

OpenEdition Journals member – Published with Lodel – Administration only

You will be redirected to OpenEdition Search

History of Jamaican Music Essay

Natty Rebel (U-Roy). The genre of this track is reggae. The bits have splits. A lot of keyboard and trumpets are used. The soft female voices humming in the background add to the atmosphere of a typical Jamaican reggae and create an impressive contrast between the soothing sound and the rebellious protest of the lyrics.

I Shot The Sheriff (Bob Marley & The Wailers). The slow tempo makes it clear from the very start that the off-beat song belongs to the genre of reggae. In this song, Bob Marley and Waivers tell a story of how he shot and killed a Sherriff. Emphasizing that this was self-defense, the singer demands more freedom for people. The song is another mini-revolt in disguise.

I’ll Never Grow Old (The Maytals). This song also belongs to the reggae genre. The composition has an ascending beat and the consistent slow rhythm, which creates the atmosphere of suspense and anticipation. A story of a man who is searching for the love of his life, the song revolves around personal issues rather than social ones, which makes it stand out among the rest of reggae songs.

House Call (Shebba Ranks ft. Maxi Priest). Beating in a slow ascending rhythm, this reggae song also touches upon the delicate issue of love and the beauty of body language.

Zunguzung (Yellow man). Due to a relaxed, laid-back melody and the rhythmic beat, this song has taken its place in the treasure trove of the reggae hits. Revealing a not-a-care-in-the-world philosophy of a Rastafarian, this song is the essence of Jamaican music.

Girl I’ve got A Date (Alton Ellis& The Flames). This song is a rock steady genre composition. It has a mixture of reggae, pop and dance styles. Sending its audience back in the times when reggae was only beginning to gain weight, this song tells about the singer’s relationships with a girl. The phrase “I can’t stay late” seems a motto of a typical reggae singer, free as a bird and with just as little care about anything.

- Hip-Hop Theory and Culture in the Discography

- Artists in Jazz Music and Dance Development

- Reggae, Disco, and Funk Musical Styles

- “Redemption” Song by Bob Marley and The Wailers

- “The Life and Times of Bob Marley” by Mikal Gilmore

- Mystery Compositions in Church Music

- Afro-American Influence on Western Music Development

- Rock'n'Roll: Musical Genre of the Twentieth Century

- Literature Study on the Hip-Hop Concept: A Social Movement and Part of the Industry

- Hip Hop Definition

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, January 12). History of Jamaican Music. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-jamaican-music/

"History of Jamaican Music." IvyPanda , 12 Jan. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-jamaican-music/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'History of Jamaican Music'. 12 January.

IvyPanda . 2021. "History of Jamaican Music." January 12, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-jamaican-music/.

1. IvyPanda . "History of Jamaican Music." January 12, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-jamaican-music/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "History of Jamaican Music." January 12, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-jamaican-music/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Evolution in Modern Indian Music Words: 997

- The Evolution of Classical Music to Modern Times Words: 884

- Classical Arab Music Words: 1922

- Music of the Renaissance Words: 1292

- Bachata as a Music Genre and Artists’ Creativity Words: 1656

- Bachata Music and Drivers Behind Its Popularity Words: 1435

- Popular and Serious Music Words: 589

- Music Evolution and Historical Roots Words: 839

- Philosophizing About Music and Emotions Words: 1387

- The Definition and Genres of World Music Words: 884

- Researching of Music of the Caribbean Words: 858

- Music and Its Impact on Cognition and Emotions Words: 1173

- Music Therapy: Review Words: 1453

Jamaican Music’s Evolution and Forms

Introduction, mento music, jamaican rocksteady music, jamaican reggae music, jamaican music today, works cited.

When one talks about Jamaican music, the first music genre that comes to mind is reggae music by Bob Marley. However, the history of Jamaican music spans beyond the music legend. The history of Jamaican music is based on drumbeat with a bit of European influence. Today Jamaican Music has evolved over the years to include these roots and has influenced the emergence of other genres. Jamaican music has also propelled several artists to international status. In fact, without Jamaican music, musical sounds such as Mento, Reggae, Ska, and Hip-Hop would not have come to the world’s knowledge (Henry). The paper traces the evolution of these musical sounds in Jamaica and how they spread to other parts of the world.

Mento draws its musical origins from enslaved West African people. These enslaved people were often rewarded for playing music for their masters. In addition to singing, they incorporated dance into the Music (Henry), and with time, Mento came to be considered Jamaican folk music. Mento music was the first form of music predating Ska and Reggae. It combines African and European rhythmic elements, which gained popularity in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The distinguishable feature of Mento was that it solely used instruments to produce sound. Some of these instruments were but were not limited to hand drums, banjos, acoustic guitar, and the rhumba box. The rhumba box produced the bass part of the Music (Kauppila), which brought in more harmony to most Mento pieces.

Due to the similarities Mento shares with Calypso, a form of music originating from Trinidad and Tobago, Mento is often confused with Calypso. Despite the similarities, the two forms of music are separate and distinct. The confusion was more predominant in the mid-20 th century when most Mento artists used Calypso techniques and vice versa. Unlike Calypso, Mento uses topical lyrics, which contain humor to highlight major social problems such as poverty, crime, and corruption. It also had some sexual innuendoes (Perry). Mento could be considered a precursor of other forms of Music in Jamaica, such as Dancehall, which also points out social problems and contains sexual innuendoes. Although Mento is an old form of music, bands in modern Jamaica perform the music in hotels to entertain tourists.

Ska gained popularity in the 1950s as it emerged from the Mento genre. Musicians adding other techniques into Mento music from other forms of music such as Calypso, American Jazz, Blues, and so on choreographed the emergence of Ska. The distinguishing feature of Ska is that it features a bass line accompanied by an offbeat rhythm. Notable musicians who popularized Ska were Prince Buster, Clement Dodd, and Stranger Cole after forming sound systems and playing American Blues. Over time, in the early 1960s, Ska had become the most popular music genre in Jamaica (Perry). Some of the popular songs from famous artists that were initially Ska music are “Oh Carolina” by the Folkes Brothers , the very popular “My Boy Lollipop” by Millie Small , and “Simmer Down” by the Wailers in 1963. Legends such as Bob Marley and Toots Hibert began their music career with Ska music (Henry). Other countries that embraced Ska music were the United States and the United Kingdom. Chris Blackwell Island Records was one of the labels in the 1960s, which popularized Jamaica Ska music by recording several songs by Ska artists.

Similar to past music genres such as Ska, Rocksteady incorporated music elements such as jazz, blues, and African drumming. The Rocksteady music genre originated from Jamaica around 1966 (BBC). It is considered the successor of Ska and predecessor of reggae music. After its discovery, Rocksteady dominated the Jamaican music industry for two years. During the two years, music groups such as the Paragons, the Hepstones, and the Techniques produced popular songs under the Rocksteady music genre. Solo musicians who created songs using Rocksteady techniques were Alton Ellis and Delroy Wilson. The name Rocksteady was coined from a popular dance style witnessed in Alton Ellis song “Rocksteady,” which matched the song’s rhythm (ZonaReGGae). Over time, the music genre became popular to capture international attention when popular Rocksteady songs became hits internationally. This helped lay out the strong foundation reggae enjoys today.

Reggae is the most famous music genre known to have originated from Jamaica in the late 1960s. By the 1970s, it has gained international recognition being popular in the US, UK, and Africa. It was mainly regarded as the voice of the oppressed (Cooper). Reggae, like its predecessors, was based on Ska, Rocksteady, and Mento but applied a heavy rhythm accompanied by drums, electric, and bass guitar. The music is associated with the Rastafari religion, which gained popularity in the 1930s and promoted pan-Africanism. The Rastafari religion assisted reggae music in gaining international recognition by helping in spreading the Rastafari gospel (Warner). Like other forms of music, Reggae draws heavily from African folk song rhythms with a bit of European touch due to the introduction of the guitar and piano. Some of the popular musicians of reggae music were Bob Marley, the Wailers, and the Skatalites, among others.

Although most of the pioneers of Jamaican Reggae, such as Bob Marley and the Wailers, died, the reggae music still reigns continues. With the advancement in music recording technology in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Jamaican music industry was revolutionized, leading to the creation of Ragga. This generic form of reggae music was marked with simplistic lyrics, paving the way for young artists to make their mark in the local and international music scene. Contemporary musicians such as Sean Paul, Beenie Man, and Shaggy, among others, continue to sell reggae music to the world. The raga genre comes in several forms, including roots, lovers rock, and Rastafarian (Henry). This has made reggae music popular in most parts of the world because the various categories target a specific demographic.

Jamaican music finds its origin in enslaved West Africans who sang for their masters and got rewarded for the skill. This form of music was known as the Mento, which only involved acoustic performance. Ska, which in addition to acoustics, included some form of dance and some European touch in the form of pianos and bass guitars. The Rocksteady music was a slight variation of Ska, which incorporated jazz and blues in its rendition. Finally, the reggae music included all the elements of Mento, Ska, and Rocksteady.

BBC. “BBC Four – Rocksteady: The Roots of Reggae.” BBC , 2011. Web.

Cooper, Carolyn J. “Reggae | Music.” Encyclopædia Britannica , 2016. Web.

Henry, Ricardo. “Jamaican Music – from Mento to Dancehall.” Jamaica Land We Love . Web.

Perry, Andrew. “ Chris Blackwell Interview: Island Records. “ telegraph. 2009. Web.

“Shaping Freedom, Finding Unity – the Power of Music Displayed in Early Mento.” Jamaica-Gleaner. Web.

Warner, Keith Q. “Calypso, Reggae, and Rastafarianism: Authentic Caribbean Voices.” Popular Music and Society , vol. 12, no. 1. 1988, pp. 53–62.

ZonaReGGae. “ZonaReGGae Reviews’ Many Moods of…Alton Ellis.’” ZonaReGGaeRadioshow , 2007. Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2023, May 27). Jamaican Music’s Evolution and Forms. https://studycorgi.com/jamaican-musics-evolution-and-forms/

"Jamaican Music’s Evolution and Forms." StudyCorgi , 27 May 2023, studycorgi.com/jamaican-musics-evolution-and-forms/.

StudyCorgi . (2023) 'Jamaican Music’s Evolution and Forms'. 27 May.

1. StudyCorgi . "Jamaican Music’s Evolution and Forms." May 27, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/jamaican-musics-evolution-and-forms/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Jamaican Music’s Evolution and Forms." May 27, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/jamaican-musics-evolution-and-forms/.

StudyCorgi . 2023. "Jamaican Music’s Evolution and Forms." May 27, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/jamaican-musics-evolution-and-forms/.

This paper, “Jamaican Music’s Evolution and Forms”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: September 18, 2024 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Green Global Travel

World's largest independently owned Ecotourism / Green Travel / Sustainable Travel / Animal & Wildlife Conservation site. We share transformative Responsible Travel, Sustainable Living & Going Green Tips that make a positive impact.

The History of Jamaican Music Genres (From Ska and Reggae to Dub)

Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links. All hosted affiliate links follow our editorial policies .

Measuring just 145 miles long and 50 miles wide, with a population of around 2.8 million, Jamaica ranks 139th among the world’s most populous countries (putting it just ahead of Mongolia and Latvia).

But it’s impossible to quantify the remarkable impact the island has had on global culture, thanks in large part to a legacy of musical innovation stretching back over 50 years.

Without Jamaican music genres such as ska, reggae and dub (all of which were born on this tiny island in the West Indies), popular artists such as The Police, No Doubt, the Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Sublime, and Skrillex might never have existed.

Here’s a brief look at the rich history of Jamaican music, including our picks for the most influential Jamaican musicians and their must-own albums.

READ MORE: Top 10 Things to Do in Jamaica (For Nature Lovers)

ROCKSTEADY: A BRIEF SKA HISTORY

Though most people associate the island with the laid-back rhythms of reggae, Jamaica’s first major musical movement was the more uptempo sound of ska.

Combining elements of Caribbean mento and calypso with American jazz and rhythm & blues, ska arose in the wake of American soldiers stationed in Jamaica during and after World War II. Its celebratory sound coincided with Jamaica’s independence from the UK in 1962.

Early acts such as The Skatalites and The Wailers remain legends today, influencing ‘80s acts such as Madness, The Specials and English Beat and ‘90s icons such as Sublime, No Doubt and the Mighty Mighty Bosstones.

But by the late ‘60s, as American soul music was becoming slower and smoother, ska began to evolve into reggae. Led by artists such as Bob Marley, Burning Spear, and Peter Tosh, reggae’s central themes of peace, love, justice, and equality mirrored the ideals of the American counter-cultural movement of the same era.

READ MORE: Interview with Reggae Music Legends The Wailers

ONE LOVE: REGGAE MUSIC HISTORY

The dawn of reggae found Jamaican music spreading throughout the world, with Bob Marley & the Wailers leading the charge.

With lyrics that balanced sociopolitical discourse, religious themes and messages of love and positivity, songs such as “Get Up, Stand Up” and “I Shot the Sheriff” made them international superstars (particularly after the latter was covered by Eric Clapton in 1974).

But they weren’t the only Jamaican musicians to break out on the roots reggae scene. Prominent acts such as ex-Wailer Peter Tosh, Jimmy Cliff, Burning Spear , Black Uhuru, Toots & the Maytals, Israel Vibration, and Culture all emerged as stars on the global stage.

Wailers producer Lee “Scratch” Perry was chosen to work with British punk legends The Clash, while British bands such as The Police and Steel Pulse proved reggae’s influence was spreading far beyond Jamaica’s borders.

In 1985, the Grammy Awards introduced a Best Reggae Album category, signaling the Jamaican sound’s firm place in the mainstream. READ MORE: Ziggy Marley on Jamaica, Ganga & Reggae Music

THE BRANCHES: DUB MUSIC & BEYOND

While the influence of ska and reggae cannot be overstated, it was another Jamaican music sub-genre that ultimately changed the world.

Popularized by production wizards such as Lee “Scratch” Perry and King Tubby , dub is a largely instrumental version of reggae that was originally used to test sound systems.

The DJ would remove vocals from reggae records, remixing them to focus on the beat and toasting over the top in a chatty style that boasted of his prowess, gave shout-outs to his friends, and dissed his competitors. Sound familiar? If you love hip-hop, it should!

When Kingston native Clive “DJ Kool Herc” Campbell moved to the Bronx, his legendary parties gave birth to the sound we now know as hip-hop, influencing practically every DJ and MC that followed.

In the last two decades, a bevy of popular musical forms have evolved out of Jamaican styles, including dancehall, reggaeton, and trip-hop.

Whether it’s Bob’s son Ziggy Marley singing the theme song to the children’s TV show Arthur, pop star Sean Kingston , or the futuristic techno hybrid known as dubstep, these days Jamaican music is everywhere.

And as its sounds continue to evolve and spread all across the world, we can be sure that the little island will continue to be a big influence for many years to come.

READ MORE: The History & Evolution of Dub Music

JAMAICA ATTRACTIONS FOR MUSIC LOVERS

The Bob Marley Museum (Kingston)- This museum features the world’s largest collection of writings, photographs, artifacts, memorabilia and other mementos from the reggae legend’s extraordinary life.

The Jamaica Music Museum (Kingston)- This museum chronicles the history and evolution of the island’s music, from mento and ska to reggae, dub and dancehall.

Peter Tosh Memorial Park (Westmoreland)- This memorial (overseen by Tosh’s mother) includes his mausoleum, a small museum/gift shop and memorabilia of the legend’s life.

Reggae Xplosion Museum (Ocho Rios)- Provides an extensive overview of Jamaican music history, including digital photo archives, music-related art, vinyl albums and a replica of a mobile record shack.

About the Author

As seen on….

Join the 300,000+ people who follow Green Global Travel’s Blog and Social Media

Daddy U-Roy’s tribute to Count Machukie illuminates the profound impact of toasting on early American songs, underscoring Machukie’s enduring influence on dance enthusiasts. Reggae, synonymous with Jamaican music, is a vibrant mosaic of styles, encompassing the folk-inspired Mento of the 1950s, the soul-stirring Jamaican Gospel, the upbeat rhythms of Ska, the smooth melodies of Rocksteady, and the anthemic Festival Songs. It also includes the inventive Dubs & Specials, the tender sentiments of Reggae Love Songs (Lovers Rock), the profound messages of Root & Culture, and the high-energy beats of Dancehall. While some attempt to delineate Dancehall from reggae, the two are inextricably linked, with Dancehall forming an integral part of Jamaican music’s foundation. Each style has played a unique role in the development of both the music and Jamaican culture. Despite changes over time, all these styles remain actively part of the Jamaican music experience, with Rocksteady serving as a timeless reminder of the “good vibes” found in parties, oldies sessions, street dances, and clubs. For Jamaicans born before the 1970s, these genres are not just musical forms but a lived experience, a testament to the enduring legacy of reggae.

“It was a healing in the barnyard, Alellujah:”

“Come wi guh dung a Solas, fi guh by banana…”

In the 1950s, one Jamaican music style reigned King, serving all audiences. Mento , a fusion of African and European rhythmic sounds, peaked in popularity in the 1940s and 1950s. While Trinidad bragged about its calypso sound across the Caribbean, the unique sound of mento was famous in Jamaica. Instruments that make the distinctive sound of mento include the acoustic guitar, banjo, rhumba box, and hand drum. The rhumba box provided the bass. Mento goes along with a special kind of dance: the Quadrille. Without delving into the three types of Quadrille (Ballroom Style, Camp Style, and Contra Style), mento compliments the Jamaican Contra Style Quadrille performed from beginning to end of the mento song. In earlier decades, Mento was the music of choice for entertaining visitors. It is still predominantly found in hotels across the North Coast, the tourism sector, and schools that compete in cultural dance and song competitions.

Jamaican Gospel

“There’ll be singing, there’ll be shouting when the saints go marching home…”

“Im gonna lay down my burdens, down by the riverside…Down by!…”

“Study war no more… I ain’t going to study war no more…”

Jamaican Gospe l songs, like reggae music, have come a long way. The genre is highly spiritual, with oversight of God ever-present. It has evolved from the Jim Reeves, Mahalia Jackson, and Praise & Worship tradition into various streams, such as Mento gospel, Festival Song Gospel, Reggae Gospel, and Dancehall Gospel . The Mento Gospel , for example, invoked a “getting-into-the-spirit” and “God-moving-in-the-body, shaking and speaking in tongues kind of dancing. Lately, the new streams moved into a type of religious celebration and dance made famous by singers such as Papa San , Junior Tucker, Lieutenant Stitchie, and Marion Hall . More recently, we have seen the emergence of the duppy band, which involves the live band playing Mento Gospel m usic at nine nights, wakes, and funerals, sparking immense excitement and an array of dance styles in sending the deceased off to heaven. Whatever the gospel style, God is in the middle.

“W ash, wash; wash all my troubles away…”

“It was Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers; Deuteronomy…”

After Jamaica moved out of the plans for a West Indies Federation, the next natural move was to push for an independent nation. That sparked a shift in the music. Mento was replaced by Ska , a more upbeat, vibrant, and triumphant sound that matched the excitement of a people who were “ridding themselves of the Monarchy” (or so they thought). Ska combines the feeling of mento and calypso with American jazz, twist, rhythm, and blues. The cello replaced the rhumba box for bass, the horn section, and the rhythm guitars, creating music for the top-end sound with the walking bass line accented with rhythms on the off-beat. These were exciting times, and people started to snap-fall, shuffle, twist, and wash the night away. Ska music was not for lovers or the faint of heart. Instead, it was fast-paced jumping, falling to the ground with the body shifting from place to place. It was perfect as Independence rolled around in August 1962. Ska had a fast tempo, and people danced to lyrical and instrumental ska music by artists such as Stranger Cole, Prince Buster, Derrick Morgan, Byron Lee, Skatalites, and Jimmy Cliff.

Reggae Love Song (Lovers Rock)

“If I had a pair of wings over the prison walls, I’d fly…”

“As I write this letter, my heart’s beating much too fast for my pen…”