An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

An Examination of US School Mass Shootings, 2017–2022: Findings and Implications

Antonis katsiyannis.

1 Department of Education and Human Development, College of Education, Clemson University, 101 Gantt Circle, Room 407 C, Clemson, SC 29634 USA

Luke J. Rapa

2 Department of Education and Human Development, College of Education, Clemson University, 101 Gantt Circle, Room 409 F, Clemson, SC 29634 USA

Denise K. Whitford

3 Steven C. Beering Hall of Liberal Arts and Education, Purdue University, 100 N. University Street, BRNG 5154, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2098 USA

Samantha N. Scott

4 Department of Education and Human Development, College of Education, Clemson University, 101 Gantt Circle, Room G01A, Clemson, SC 29634 USA

Gun violence in the USA is a pressing social and public health issue. As rates of gun violence continue to rise, deaths resulting from such violence rise as well. School shootings, in particular, are at their highest recorded levels. In this study, we examined rates of intentional firearm deaths, mass shootings, and school mass shootings in the USA using data from the past 5 years, 2017–2022, to assess trends and reappraise prior examination of this issue.

Extant data regarding shooting deaths from 2017 through 2020 were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, the web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS), and, for school shootings in particular (2017–2022), from Everytown Research & Policy.

The number of intentional firearm deaths and the crude death rates increased from 2017 to 2020 in all age categories; crude death rates rose from 4.47 in 2017 to 5.88 in 2020. School shootings made a sharp decline in 2020—understandably so, given the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent government or locally mandated school shutdowns—but rose again sharply in 2021.

Conclusions

Recent data suggest continued upward trends in school shootings, school mass shootings, and related deaths over the past 5 years. Notably, gun violence disproportionately affects boys, especially Black boys, with much higher gun deaths per capita for this group than for any other group of youth. Implications for policy and practice are provided.

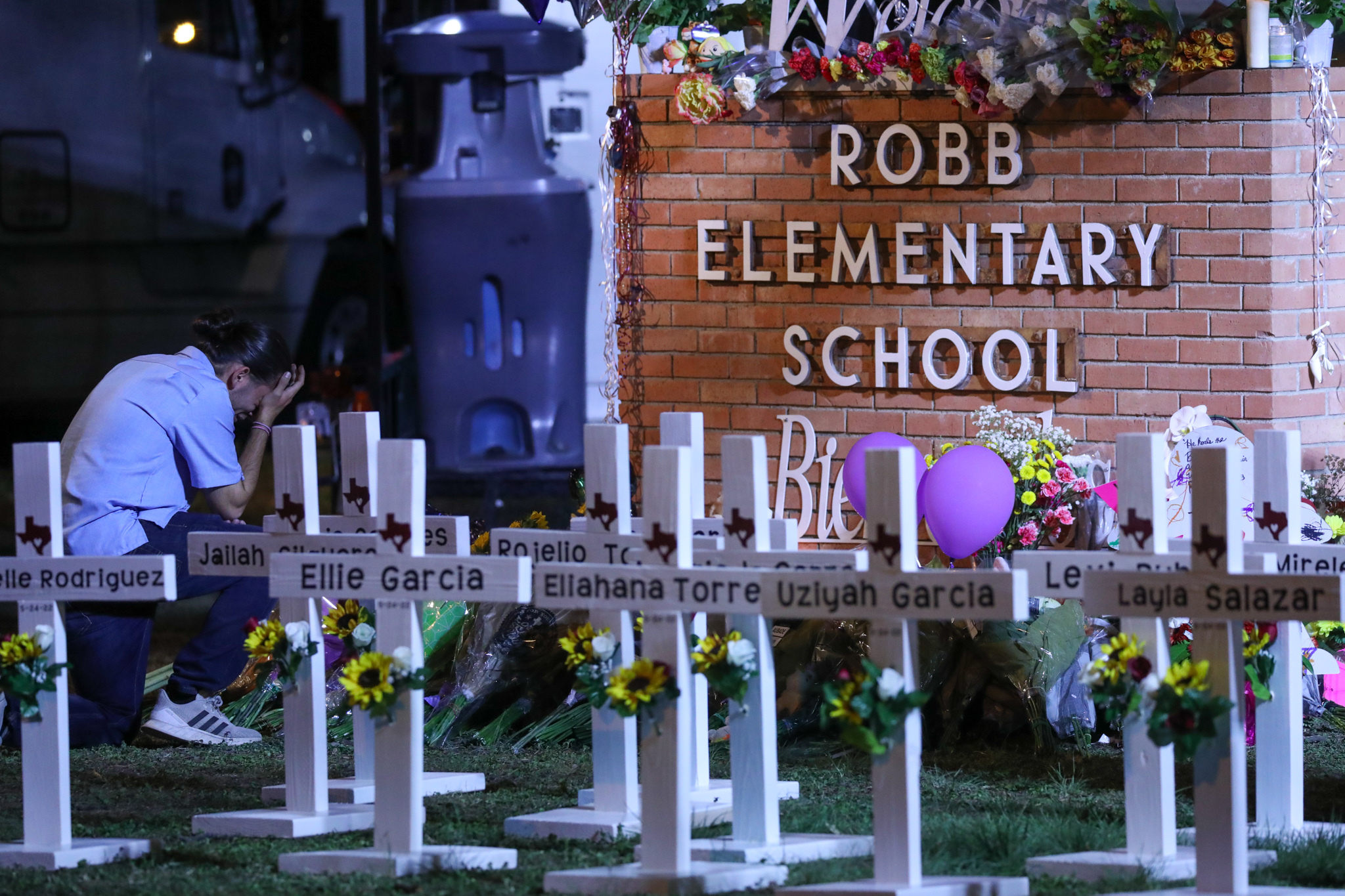

On May 24, 2022, an 18-year-old man killed 19 students and two teachers and wounded 17 individuals at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, TX, using an AR-15-style rifle. Outside the school, he fired shots for about 5 min before entering the school through an unlocked side door and locked himself inside two adjoining classrooms killing 19 students and two teachers. He was in the school for over an hour (78 min) before being shot dead by the US Border Patrol Tactical Unit, though police officers were on the school premises (Sandoval, 2022 ).

The Robb Elementary School mass shooting, the second deadliest school mass shooting in American history, is the latest calamity in a long list of tragedies occurring on public school campuses in the USA. Regrettably, these tragedies are both a reflection and an outgrowth of the broader reality of gun violence in this country. In 2021, gun violence claimed 45,027 lives (including 20,937 suicides), with 313 children aged 0–11 killed and 750 injured, along with 1247 youth aged 12–17 killed and 3385 injured (Gun Violence Archive, 2022a ). Mass shootings in the USA have steadily increased in recent years, rising from 269 in 2013 to 611 in 2020. Mass shootings are typically defined as incidents in which four or more people are killed (Katsiyannis et al., 2018a ). However, the Gun Violence Archive considers mass shootings to be incidents in which four or more people are injured (Gun Violence Archive, 2022b ). Regardless of these distinctions in definition, in 2020, there were 19,384 gun murders, representing a 34% increase from the year before, a 49% increase over a 5-year period, and a 75% increase over a 10-year period (Pew Research Center, 2022 ). Regarding school-based shootings, to date in 2022, there have been at least 95 incidents of gunfire on school premises, resulting in 40 deaths and 76 injuries (Everytown Research & Policy, 2022b ). Over the past few decades, school shootings in the USA have become relatively commonplace: there were more in 2021 than in any year since 1999, with the median age of perpetrators being 16 (Washington Post, 2022 ; see also, Katsiyannis et al., 2018a ). Additionally, analysis of Everytown’s Gunfire on School Grounds dataset and related studies point to several key observations to be considered in addressing this challenge. For example, 58% of perpetrators had a connection to the school, 70% were White males, 73 to 80% obtained guns from home or relatives or friends, and 100% exhibited warning signs or showed behavior that was of cause for concern; also, in 77% of school shootings, at least one person knew about the shooter’s plan before the shooting events occurred (Everytown Research & Policy, 2021a ).

The USA has had 57 times as many school shootings as all other major industrialized nations combined (Rowhani-Rahbar & Moe, 2019 ). Guns are the leading cause of death for children and teens in the USA, with children ages 5–14 being 21 times and adolescents and young adults ages 15–24 being 23 times more likely to be killed with guns compared to other high-income countries. Furthermore, Black children and teens are 14 times and Latinx children and teens are three times more likely than White children to die by guns (Everytown Research & Policy, 2021b ). Children exposed to violence, crime, and abuse face a host of adverse challenges, including abuse of drugs and alcohol, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, school failure, and involvement in criminal activity (Cabral et al., 2021 ; Everytown Research and Policy, 2022b ; Finkelhor et al., 2013 ).

Yet, despite gun violence being considered a pressing social and public health issue, federal legislation passed in 1996 has resulted in restricting funding for the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The law stated that no funding earmarked for injury prevention and control may be used to advocate or promote firearm control (Kellermann & Rivara, 2013 ). More recently, in June 2022, the US Supreme Court struck down legislation restricting gun possession and open carry rights (New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn., Inc. v. Bruen, 2021 ), broadening gun rights and increasing the risk of gun violence in public spaces. Nonetheless, according to Everytown Research & Policy ( 2022a ), states with strong gun laws experience fewer deaths per capita. In the aggregate, states with weaker gun laws (i.e., laws that are more permissive) experience 20.0 gun deaths per 100,000 residents versus 7.4 per 100,000 in states with stronger laws. The association between gun law strength and per capita death is stark (see Table Table1 1 ).

Gun law strength and gun law deaths per 100,000 residents

Accounting for the top eight and the bottom eight states in gun law strength, gun law strength and gun deaths per 100,000 are correlated at r = − 0.85. Stronger gun laws are thus meaningfully linked with fewer deaths per capita. Data obtained from Everytown Research & Policy ( 2022a )

Notwithstanding the publicity involving gun shootings in schools, particularly mass shootings, violence in schools has been steadily declining. For example, in 2020, students aged 12–18 experienced 285,400 victimizations at school and 380,900 victimizations away from school; an annual decrease of 60% for school victimizations (from 2019 to 2020) (Irwin et al., 2022 ). Similarly, youth arrests in general in 2019 were at their lowest level since at least 1980; between 2010 and 2019, the number of juvenile arrests fell by 58%. Yet, arrests for murder increased by 10% (Puzzanchera, 2021 ).

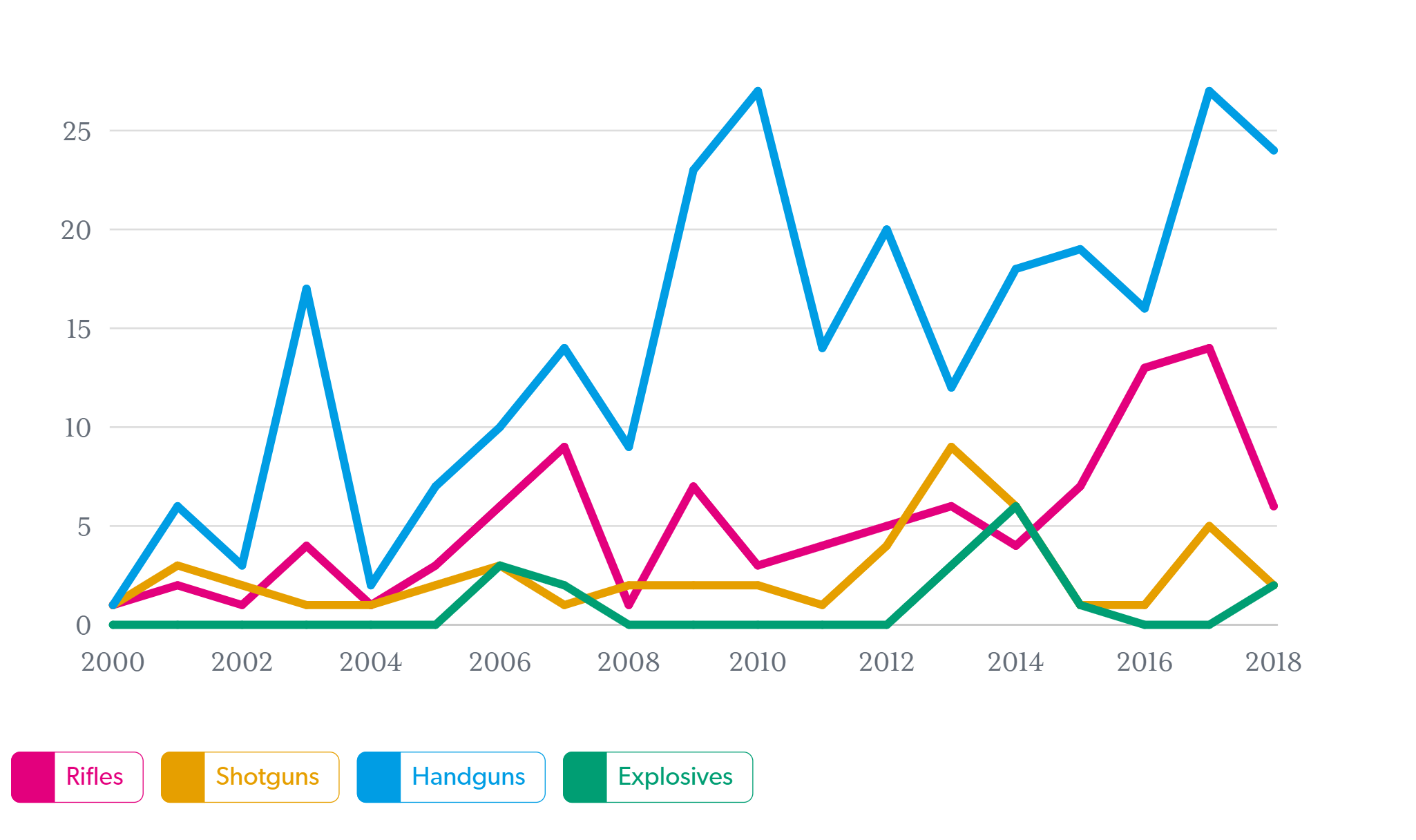

In response to school violence in general, and school shootings in particular, schools have increasingly relied on increased security measures, school resource officers (SROs), and zero tolerance policies (including exclusionary and aversive measures) in their attempts to curb violence and enhance school safety. In 2019–2020, public schools reported controlled access (97%), the use of security cameras (91%), and badges or picture IDs (77%) to promote safety. In addition, high schools (84%), middle schools (81%), and elementary schools (55%) reported the presence of SROs (Irwin et al., 2022 ). Research, however, has indicated that the presence of SROs has not resulted in a reduction of school shooting severity, despite their increased prevalence. Rather, the type of firearm utilized in school shootings has been closely associated with the number of deaths and injuries (Lemieux, 2014 ; Livingston et al., 2019 ), suggesting implications for reconsideration of the kinds of firearms to which individuals have access.

Zero tolerance policies, though originally intended to curtail gun violence in schools, have expanded to cover a host of incidents (e.g., threats, bullying). Notwithstanding these intentions, these policies are generally ineffective in preventing school violence, including school shootings (American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008 ; Losinski et al., 2014 ), and have exacerbated the prevalence of youths’ interactions with law enforcement in schools. From the 2015–2016 to the 2017–2018 school years, there was a 5% increase in school-related arrests and a 12% increase in referrals to law enforcement (U.S. Department of Education, 2021 ); in 2017–18, about 230,000 students were referred to law enforcement and over 50,000 were arrested (The Center for Public Integrity, 2021 ). Law enforcement referrals have been a persistent concern aiding the school-to-prison pipeline, often involving non-criminal offenses and disproportionally affecting students from non-White backgrounds as well as students with disabilities (Chan et al., 2021 ; The Center for Public Integrity, 2021 ).

The consequences of these policies are thus far-reaching, with not only legal ramifications, but social-emotional and academic ones as well. For example, in 2017–2018, students missed 11,205,797 school days due to out-of-school suspensions during that school year (U.S. Department of Education, 2021 ), there were 96,492 corporal punishment incidents, and 101,990 students were physically restrained, mechanically restrained, or secluded (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights, 2020 ). Such exclusionary and punitive measures have long-lasting consequences for the involved students, including academic underachievement, dropout, delinquency, and post-traumatic stress (e.g., Cholewa et al., 2018 ). Moreover, these consequences disproportionally affect culturally and linguistically diverse students and students with disabilities (Skiba et al., 2014 ; U.S. General Accountability Office, 2018 ), often resulting in great societal costs (Rumberger & Losen, 2017 ).

In the USA, mass killings involving guns occur approximately every 2 weeks, while school shootings occur every 4 weeks (Towers et al., 2015 ). Given the apparent and continued rise in gun violence, mass shootings, and school mass shootings, we aimed in this paper to reexamine rates of intentional firearm deaths, mass shootings, and school mass shootings in the USA using data from the past 5 years, 2017–2022, reappraising our analyses given the time that had passed since our earlier examination of the issue (Katsiyannis et al., 2018a , b ).

As noted in Katsiyannis et al., ( 2018a , b ), gun violence, mass shootings, and school shootings have been a part of the American way of life for generations. Such shootings have grown exponentially in both frequency and mortality rate since the 1980s. Using the same criteria applied in our previous work (Katsiyannis et al., 2018a , b ), we evaluated the frequency of shootings, mass shootings, and school mass school shootings from January 2017 through mid-July 2022. Extant data regarding shooting deaths from 2017 through 2020 were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, utilizing the web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS), and for school shootings from 2017 to 2022 from Everytown Research & Policy ( https://everytownresearch.org ), an independent non-profit organization that researches and communicates with policymakers and the public about gun violence in the USA. Intentional firearm death data were classified by age, as outlined in Katsiyannis et al., ( 2018a , b ), and the crude rate was calculated by dividing the number of deaths times 100,000, by the total population for each individual category.

The number of intentional firearm deaths and the crude death rates increased from 2017 to 2020 in all age categories. In absolute terms, the number of deaths rose from 14,496 in 2017 to 19,308 in 2020. In accord with this rise in the absolute number of deaths, crude death rates rose from 4.47 in 2017 to 5.88 in 2020. Table Table2 2 provides the crude death rate in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, the most current years with data available. Figure 1 provides the raw number of deaths across the same time period.

Intentional firearm deaths across the USA (2017–2020)

Data obtained from WISQARS (2022)

Intentional firearm deaths across the USA (2017–2020). Note. Data obtained from WISQARS (2022)

As expected, in 2020, the number of fatal firearm injuries increased sharply from age 0–11 years, roughly elementary school age, to age 12–18 years, roughly middle school and high school age. Table Table3 3 provides the crude death rates of children in 2020 who die from firearms. Males outnumbered females in every category of firearm deaths, including homicide, police violence, suicide, and accidental shootings, as well as for undetermined reasons for firearm discharge. Black males drastically surpassed all other children in the number of firearm deaths (2.91 per 100,000 0–11-year-olds; 57.10 per 100,000 12–18-year-olds). Also, notable is the high number of Black children 12–18 years killed by guns (32.37 per 100,000), followed by American Indian and Alaska Native children (18.87 per 100,000), in comparison to White children (12.40 per 100,000 children), Hispanic/Latinx children (8.16 per 100,000), and Asian and Pacific Islander children (2.95 per 100,000). A disproportionate number of gun deaths were also seen for Black girls relative to other girls (1.52 per 100,000 0–11-year-olds; 7.01 per 100,000 12–18-year-olds).

Fatal firearm injuries for children age 0–18 across the USA in 2020

AN Alaska Native; – indicates 20 or fewer cases

Mass shootings and mass shooting deaths increased from 2017 to 2019, decreased in 2020, and then increased again in 2021. School shootings made a sharp decline in 2020—understandably so, given the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent government or locally mandated school shutdowns—but rose again sharply in 2021. Current rates reveal a continued increase, with numbers at the beginning of 2022 already exceeding those of 2017. School mass shooting counts were relatively low between 2017 through 2022, with four total during that time frame. Figure 2 provides raw numbers for mass shootings, school shootings, and school mass shootings from 2017 through 2022. Importantly, figures from the recent Uvalde, TX, school mass shooting at Robb Elementary School had not yet been recorded in the relevant databases at the time of this writing. With those deaths accounted for, 2022 is already the deadliest year for school mass shootings in the past 5 years.

Mass shootings, school shootings, and mass school shootings across the USA (2017–2022). Note. Data obtained from Everytown Research and Policy. Overlap present between all three categories

Gun violence in the USA, particularly mass shootings on the grounds of public schools, continues to be a pressing social and public health issue. Recent data suggest continued upward trends in school shootings, school mass shootings, and related deaths over the past 5 years—patterns that disturbingly mirror general gun violence and intentional shooting deaths in the USA across the same time period. The impacts on our nation’s youth are profound. Notably, gun violence disproportionately affects boys, especially Black boys, with much higher gun deaths per capita for this group than for any other group of youth. Likewise, Black girls are disproportionately affected compared to girls from other ethnic/racial groups. Moreover, while the COVID-19 pandemic and school shutdowns tempered gun violence in schools at least somewhat during the 2020 school year—including school shootings and school mass shootings—trend data show that gun violence rates are still continuing to rise. Indeed, gun violence deaths resulting from school shootings are at their highest recorded levels ever (Irwin et al., 2022 ).

Implications for Schools: Curbing School Violence

In recent years, the implementation of Multi-Tier Systems and Supports (MTSS), including Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and Response to Intervention (RTI), has resulted in improved school climate and student engagement as well as improved academic and behavioral outcomes (Elrod et al., 2022 ; Santiago-Rosario et al., 2022 ; National Center for Learning Disabilities, n.d.). Such approaches have implications for reducing school violence as well. PBIS uses a tiered framework intended to improve student behavioral and academic outcomes; it creates positive learning environments through the implementation of evidence-based instructional and behavioral interventions, guided by data-based decision-making and allocation of students across three tiers. In Tier 1, schools provide universal supports to all students in a proactive manner; in Tier 2, supports are aimed to students who need additional academic, behavioral, or social-emotional intervention; and in Tier 3, supports are provided in an intensive and individualized manner (Lewis et al., 2010 ). The implementation of PBIS has resulted in an improved school climate, fewer office referrals, and reductions in out-of-school suspensions (Bradshaw et al., 2010 ; Elrod et al., 2010 , 2022 ; Gage et al., 2018a , 2018b ; Horner et al., 2010 ; Noltemeyer et al., 2019 ). Likewise, RTI aims to improve instructional outcomes through high-quality instruction and universal screening for students to identify learning challenges and similarly allocates students across three tiers. In Tier 1, schools implement high-quality classroom instruction, screening, and group interventions; in Tier 2, schools implement targeted interventions; and in Tier 3, schools implement intensive interventions and comprehensive evaluation (National Center for Learning Disabilities, n.d ). RTI implementation has resulted in improved academic outcomes (e.g., reading, writing) (Arrimada et al., 2022 ; Balu et al., 2015 ; Siegel, 2020 ) and enhanced school climate and student behavior.

In order to support students’ well-being, enhance school climate, and support reductions in behavioral issues and school violence, schools should consider the implementation of MTSS, reducing reliance on exclusionary and aversive measures such as zero tolerance policies, seclusion and restraints, corporal punishment, or school-based law enforcement referrals and arrests (see Gage et al., in press ). Such approaches and policies are less effective than the use of MTSS, exacerbate inequities and enhance disproportionality (particularly for youth of color and students with disabilities), and have not been shown to reduce violence in schools.

Implications for Students: Ensuring Physical Safety and Supporting Mental Health

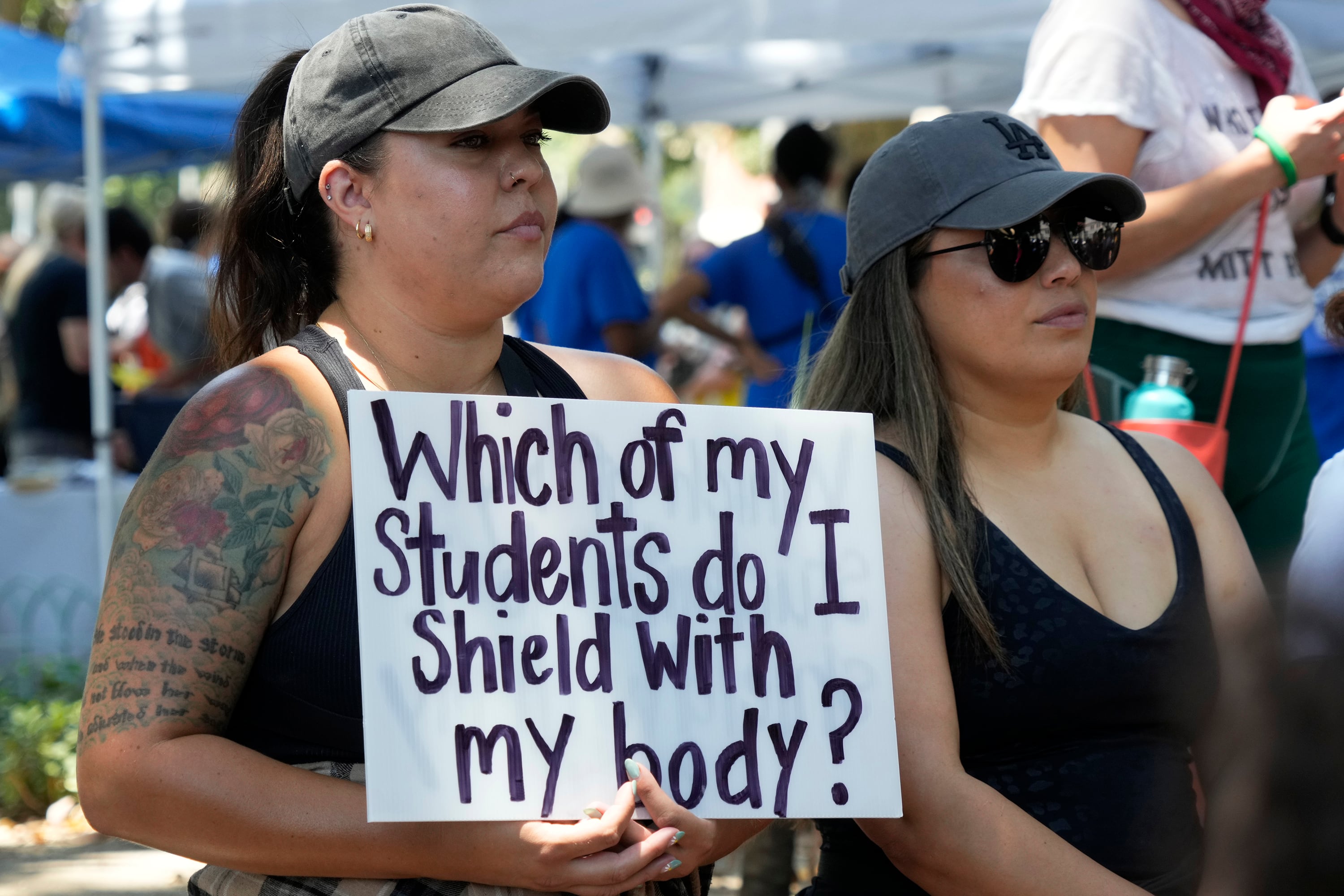

Students should not have to attend school and fear becoming victims of violence in general, no less gun violence in particular. Schools must ensure the physical safety of their students. Yet, as the substantial number of school shootings continues to rise in the USA, so too does concern about the adverse impacts of violence and gun violence on students’ mental health and well-being. Students are frequently exposed to unavoidable and frightening images and stories of school violence (Child Development Institute, n.d. ) and are subject to active shooter drills that may not actually be effective and, in some cases, may actually induce trauma (Jetelina, 2022 ; National Association of School Psychologists & National Association of School Resources Officers, 2021 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). In turn, students struggle to process and understand why these events happen and, more importantly, how they can be prevented (National Association of School Psychologists, 2015 ). School personnel should be prepared to support the mental health needs of students, both in light of the prevalence of school gun violence and in the aftermath of school mass shootings.

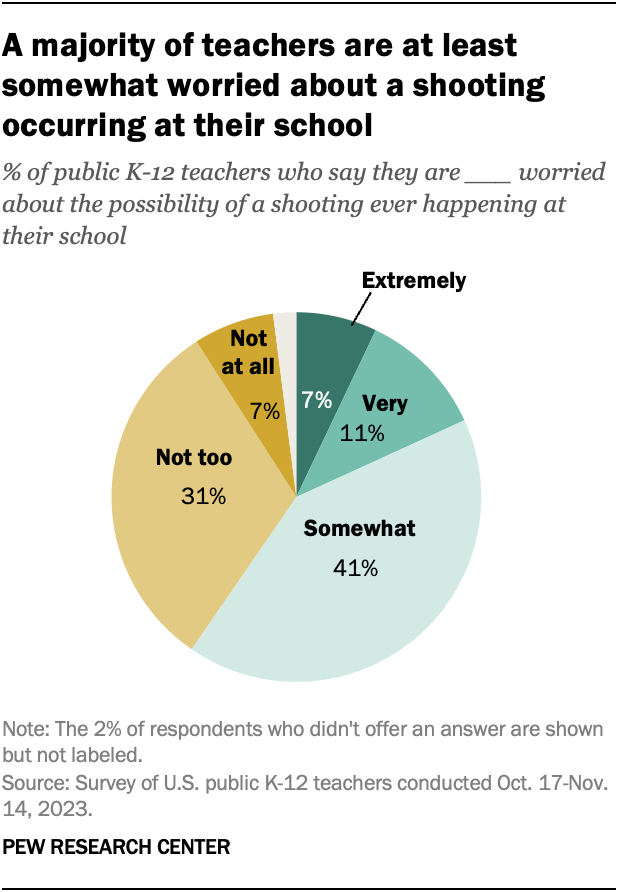

Research provides evidence that traumatic events, such as school mass shootings, can and do have mental health consequences for victims and members of affected communities, leading to an increase in post-traumatic stress syndrome, depression, and other psychological systems (Lowe & Galea, 2017 ). At the same time, high media attention to such events indirectly exposes and heightens feelings of fear, anxiety, and vulnerability in students—even if they did not attend the school where the shooting occurred (Schonfeld & Demaria, 2020 ). Students of all ages may experience adjustment difficulties and engage in avoidance behaviors (Schonfeld & Demaria, 2020 ). As a result, school personnel may underestimate a student’s distress after a shooting and overestimate their resilience. In addition, an adult’s difficulty adjusting in the wake of trauma may also threaten a student’s sense of well-being because they may believe their teachers cannot provide them with the protection they need to remain safe in school (Schonfeld & Demaria, 2020 ).

These traumatic events have resounding consequences for youth development and well-being. However, schools continue to struggle to meet the demands of student mental health needs as they lack adequate funding for resources, student support services, and staff to provide the level of support needed for many students (Katsiyannis et al., 2018a ). Despite these limiting factors, children and youth continue to look to adults for information and guidance on how to react to adverse events. An effective response can significantly decrease the likelihood of further trauma; therefore, all school personnel must be prepared to talk with students about their fears, to help them feel safe and establish a sense of normalcy and security in the wake of tragedy (National Association of School Psychologists, 2016 ). Research suggests a number of strategies can be utilized by educators, school leaders, counselors, and other mental health professionals to support the students and staff they serve.

Recommendations for Educators

The National Association of School Psychologists ( 2016 ) recommends the following practices for educators to follow in response to school mass shootings. Although a complex topic to address, the issue needs to be acknowledged. In particular, educators should designate time to talk with their students about the event, and should reassure students that they are safe while validating their fears, feelings, and concerns. Recognizing and stressing to students that all feelings are okay when a tragedy occurs is essential. It is important to note that some students do not wish to express their emotions verbally. Other developmentally appropriate outlets, such as drawing, writing, reading books, and imaginative play, can be utilized. Educators should also provide developmentally appropriate explanations of the issue and events throughout their conversations. At the elementary level, students need brief, simple answers that are balanced with reassurances that schools are safe and that adults are there to protect them. In the secondary grades, students may be more vocal in asking questions about whether they are truly safe and what protocols are in place to protect them at school. To address these questions, educators can provide information related to the efforts of school and community leaders to ensure school safety. Educators should also review safety procedures and help students to identify at least one adult in the building to whom they can go if they feel threatened or at risk. Limiting exposure to media and social media is also important, as developmentally inappropriate information can cause anxiety or confusion. Educators should also maintain a normal routine by keeping a regular school schedule.

Recommendations for School Leaders

Superintendents, principals, and other school administrative personnel are looked upon to provide leadership and comfort to staff, students, and parents during a tragedy. Reassurance can be provided by reiterating safety measures and student supports that are in place in their district and school (The National Association of School Psychologists, 2015 ). The NASP recommends the following practices for school leaders regarding addressing student mental health needs directly. First, school leaders should be a visible, welcoming presence by greeting students and visiting classrooms. School leaders should also communicate with the school community, including parents and students, about their efforts to maintain safe and caring schools through clear behavioral expectations, positive behavior interventions and supports, and crisis planning preparedness. This can include the development of press releases for broad dissemination within the school community. School leaders should also provide crisis training and professional development for staff, based upon assessments of needs and targeted toward identified knowledge or skill gaps. They should also ensure the implementation of violence prevention programs and curricula in school and review school safety policies and procedures to ensure that all safety issues are adequately covered in current school crisis plans and emergency response procedures.

Recommendations for Counselors and Mental Health Professionals

School counselors offer critical assistance to their buildings’ populations as they experience crises or respond to emergencies (American School Counselor Association, 2019 ; Brown, 2020 ). Two models that stand out in the literature utilized by counselors in the wake of violent events are the Preparation, Action, Recovery (PAR) model and the Prevent and prepare; Reaffirm; Evaluate; provide interventions and Respond (PREPaRE) model. PREPaRE is the only comprehensive, nationally available training curriculum created by educators for educators (The National Association of School Psychologists, n.d. ). Although beneficial, neither the PAR nor PREPaRE model directly addresses school counselors’ responses to school shootings when their school is directly affected (Brown, 2020 ). This led to the development of the School Counselor’s Response to School Shootings-Framework of Recommendations (SCRSS-FR) model, which includes six stages, each of which has corresponding components for school counselors who have lived through a school mass shooting. Each of these models provides the necessary training to school-employed mental health professionals on how to best fill the roles and responsibilities generated by their membership on school crisis response teams (The National Association of School Psychologists, n.d. ).

Other Implications: Federal and State Policy

Recent events at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, TX, prompted the US Congress to pass landmark legislation intended to curb gun violence, enhancing background checks for prospective gun buyers who are under 21 years of age as well as allowing examination of juvenile records beginning at age 16, including health records related to prospective gun buyers’ mental health. Additionally, this legislation provides funding that will allow states to implement “red flag laws” and other intervention programs while also strengthening laws related to the purchase and trafficking of guns (Cochrane, 2022 ). Yet, additional legislation reducing or eliminating access to assault rifles and other guns with large capacity magazines, weapons that might easily be deemed “weapons of mass destruction,” is still needed (Interdisciplinary Group on Preventing School & Community Violence, 2022 ; see also Flannery et al., 2021 ). In 2019, the US Congress started to appropriate research funding to support research on gun violence, with $25 million in equal shares provided on an annual basis from both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health (Roubein, 2022 ; Wan, 2019 ). Additional research is, of course, still needed.

Despite legislative progress, and while advancements in gun legislation are meaningful and have the potential to aid in the reduction of gun violence in the USA, school shootings and school mass shootings are something schools and students will contend with in the months and years ahead. This reality has serious implications for schools and for students, points that need serious consideration. Therefore, it is imperative that gun violence is framed as a pressing national public health issue deserving attention, with drastic steps needed to curb access to assault rifles and guns with high-capacity magazines, based on extensive and targeted research. As noted, Congress, after many years of inaction, has started to appropriate funds to address this issue. However, the level of funding is still minimal in light of the pressing challenge that gun violence presents. Furthermore, the messaging of conservative media, the National Rifle Association (NRA) and republican legislators framing access to all and any weapons—including assault rifles—as a constitutional right under the second amendment bears scrutiny. Indeed, the second amendment denotes that “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Security of the nation is arguably the intent of the amendment, an intent that is clearly violated as evidenced in the ever-increasing death toll associated with gun violence in the USA.

Whereas federal legislation would be preferable, the possibility of banning assault weapons is remote (in light of recent Congressional action). Similarly, state action has been severely curtailed in light of the US Supreme Court’s decision regarding New York state law. However, data on gun fatalities and injuries, the correspondence of gun violence to laws regulating access across the world and states, and failed security measures such as armed guards posted in schools (e.g., Robb Elementary School) must be consistently emphasized. Additionally, the widespread sense of immunity for gun manufacturers should be tested in the same manner that tobacco manufacturers and opioid pharmaceuticals have been. The success against such tobacco and opioid manufacturers, once unthinkable, is a powerful precedent to consider for how the threat of gun violence against public health might be addressed.

Author Contribution

AK conceived of and designed the study and led the writing of the manuscript. LJR collaborated on the study design, contributed to the writing of the study, and contributed to the editing of the final manuscript. DKW analyzed the data and wrote up the results. SNS contributed to the writing of the study.

Declarations

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. The American Psychologist. 2008; 63 (9):852–862. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.63.9.852. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American School Counselor Association (2019). ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th edn.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

- Arrimada M, Torrance M, Fidalgo R. Response to intervention in first-grade writing instruction: A large-scale feasibility study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2022; 35 (4):943–969. doi: 10.1007/s11145-021-10211-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Balu, R., Zhu, P., Doolittle, F., Schiller, E., Jenkins, J., & Gersten, R. (2015). Evaluation of response to intervention practices for elementary school reading (NCEE 2016–4000). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Bradshaw CP, Mitchell MM, Leaf PJ. Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2010; 12 (3):133–148. doi: 10.1177/1098300709334798. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown CH. School counselors’ response to school shootings: Framework of recommendations. Journal of Educational Research and Practice. 2020; 10 (1):18. doi: 10.5590/jerap.2020.10.1.18. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cabral, M., Kim, B., Rossin-Slater, M., Schnell, M., & Schwandt, H. (2021). Trauma at school: The impacts of shootings on students’ human capital and economic outcomes. A working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved June 21, 2022, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w28311

- Chan P, Katsiyannis A, Yell M. Handcuffed in school: Legal and practice considerations. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2021; 5 (3):339–350. doi: 10.1007/s41252-021-00213-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Child Development Institute. (n.d.). How to talk to kids about violence. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://childdevelopmentinfo.com/how-to-be-a-parent/communication/talk-to-kids-violence/

- Cholewa B, Hull MF, Babcock CR, Smith AD. Predictors and academic outcomes associated with in-school suspension. School Psychology Quarterly. 2018; 33 (2):191–199. doi: 10.1037/spq0000213. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cochrane, E. (2022). Congress passes bipartisan gun legislation, clearing it for Biden. The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/us/politics/gun-control-bill-congress.html

- Elrod BG, Rice KG, Bradshaw CP, Mitchell MM, Leaf PJ. Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2010; 12 (3):133–148. doi: 10.1177/1098300709334798. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elrod BG, Rice KG, Meyers J. PBIS fidelity, school climate, and student discipline: A longitudinal study of secondary schools. Psychology in the Schools. 2022; 59 (2):376–397. doi: 10.1002/pits.22614. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Everytown Research & Policy. (2021a). Keeping our schools safe: A plan for preventing mass shootings and ending all gun violence in American schools. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://everytownresearch.org/report/preventing-gun-violence-in-american-schools/

- Everytown Research & Policy. (2021b). The impact of gun violence on children and teens. Retrieved, June 21, 2022, from https://everytownresearch.org/report/the-impact-of-gun-violence-on-children-and-teens/

- Everytown Research & Policy. (2022a). Gun law rankings. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://everytownresearch.org/rankings/

- Everytown Research & Policy. (2022b). Gunfire on school grounds in the United States. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://everytownresearch.org/maps/gunfire-on-school-grounds/

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck AM, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013; 167 (7):614–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flannery, D. J., Fox, J. A., Wallace, L., Mulvey, E., & Modzeleski, W. (2021). Guns, school shooters, and school safety: What we know and directions for change. School Psychology Review, 50 (2-3), 237–253.

- Gage NA, Lee A, Grasley-Boy N, Peshak GH. The impact of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports on school suspensions: A statewide quasi-experimental analysis. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2018; 20 (4):217–226. doi: 10.1177/1098300718768204. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gage, N. A., Rapa, L. J., Whitford, D. K., & Katsiyannis, A. (Eds.) (in press). Disproportionality and social justice in education . Springer

- Gage N, Whitford DK, Katsiyannis A. A review of schoolwide positive behavior interventions and supports as a framework for reducing disciplinary exclusions. The Journal of Special Education. 2018; 52 :142–151. doi: 10.1272/74060629214686796178874678. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gun Violence Archive. (2022a). Gun violence archives 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/past-tolls

- Gun Violence Archive. (2022b). Charts and maps. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/

- Horner RH, Sugai G, Anderson CM. Examining the evidence base for schoolwide positive behavior support. Focus on Exceptional Children. 2010; 42 (8):1–14. doi: 10.17161/fec.v42i18.6906. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Interdisciplinary Group on Preventing School and Community Violence. (2022). Call for action to prevent gun violence in the United States of America. Retrieved July 15, 2022, from https://www.dropbox.com/s/006naaah5be23qk/2022%20Call%20To%20Action%20Press%20Release%20and%20Statement%20COMBINED%205-27-22.pdf?dl=0

- Irwin, V., Wang, K., Cui, J., & Thompson, A. (2022). Report on indicators of school crime and safety: 2021 (NCES 2022–092/NCJ 304625). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Washington, DC. Retrieved July 21, 2022 from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2022092

- Jetelina, K. (2022). Firearms: What you can do right now. Retrieved July 15, 2022, from https://yourlocalepidemiologist.substack.com/p/firearms-what-you-can-do-right-now

- Katsiyannis A, Whitford D, Ennis R. Historical examination of United States school mass shootings in the 20 th and 21 st centuries: Implications for students, schools, and society. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018; 27 :2562–2573. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1096-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Katsiyannis A, Whitford D, Ennis R. Firearm violence across the lifespan: Relevance and theoretical impact on child and adolescent educational prospects. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018; 27 :1748–1762. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1035-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kellermann AL, Rivara FP. Silencing the science on gun research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013; 309 (6):549–550. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.208207. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lemieux F. Effect of gun culture and firearm laws on firearm violence and mass shootings in the United States: A multi-level quantitative analysis. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences. 2014; 9 (1):74–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis T, Jones S, Horner R, Sugai G. School-wide positive behavior support and students with emotional/behavioral disorders: Implications for prevention, identification and intervention. Exceptionality. 2010; 18 :82–93. doi: 10.1080/09362831003673168. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Livingston MD, Rossheim ME, Stidham-Hall K. A descriptive analysis of school and school shooter characteristics and the severity of school shootings in the United States, 1999–2018. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019; 64 (6):797–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.12.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Losinski M, Katsiyannis A, Ryan J, Baughan C. Weapons in schools and zero-tolerance policies. NASSP Bulletin. 2014; 98 (2):126–141. doi: 10.1177/0192636514528747. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lowe SR, Galea S. The mental health consequences of mass shootings. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2017; 18 (1):62–82. doi: 10.1177/1524838015591572. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Association of School Psychologists. (n.d.). About PREPaRE. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/professional-development/prepare-training-curriculum/aboutprepare#:~:text=Specifically%2C%20the%20PREPaRE,E%E2%80%94Evaluate%20psychological%20trauma%20risk

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2015). Responding to school violence: Tips for administrators. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis/school-violence-resources/school-violence-prevention/responding-to-school-violence-tips-for-administrators

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2016). Talking to children about violence: Tips for parents and teachers. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis/school-violence-resources/talking-to-children-about-violence-tips-for-parents-and-teachers

- National Association of School Psychologists & National Association of School Resource Officers (2021). Best practice considerations for armed assailant drills in schools. Bethesda, MD: Author. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis/systems-level-prevention/best-practice-considerations-for-armed-assailant-drills-in-schools

- National Center for Learning Disabilities. (n.d.). What is RTI? Retrieved July 21, 2022 from http://www.rtinetwork.org/learn/what/whatisrti

- New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn., Inc. v. Bruen, 20–843. (United States Supreme Court, 2021). Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-843_7j80.pdf

- Noltemeyer A, Palmer K, James AG, Wiechman S. School-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports (SWPBIS): A synthesis of existing research. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. 2019; 7 :253–262. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2018.1425169. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pew Research Center. (2022). What the data says about gun deaths in the U.S. Retrieved June 21, 2022 from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/02/03/what-the-data-says-about-gun-deaths-in-the-u-s/

- Puzzanchera, C. (2021). Juvenile arrests, 2019 . U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. Juvenile Justice Statistics National Report Series Bulletin. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/publications/juvenile-arrests-2019.pdf

- Roubein, R. (2022). Now the government is funding gun violence research, but it’s years behind. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 17, 2022 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/05/26/now-government-is-funding-gun-violence-research-it-years-behind/

- Rowhani-Rahbar A, Moe C. School shootings in the U.S.: What is the state of evidence? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019; 64 (6):683–684. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.016. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rumberger, R. W., & Losen, D. J. (2017). The hidden costs of California’s harsh school discipline: And the localized economic benefits from suspending fewer high school students . California Dropout Research Project : The Civil Rights Project. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/resources/projects/center-for-civil-rights-remedies/school-to-prison-folder/summary-reports/the-hidden-cost-of-californias-harsh-discipline/CostofSuspensionReportFinal-corrected-030917.pdf

- Sandoval, E. (2022). Inside a Uvalde classroom: A taunting gunman and 78 minutes of terror. The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/10/us/uvalde-injured-teacher-reyes.html

- Santiago-Rosario, M. R., McIntosh, K., & Payno-Simmons, R. (2022). Centering equity within the PBIS framework: Overview and evidence of effectiveness. Center on PBIS, University of Oregon. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from www.pbis.org

- Schonfeld DJ, Demaria T. Supporting children after school shootings. Pediatric Clinics. 2020; 67 (2):397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.12.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Skiba RJ, Arredondo MI, Williams NT. More than a metaphor: The contribution of exclusionary discipline to a school-to-prison pipeline. Equity & Excellence in Education. 2014; 47 (4):546–564. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2014.958965. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Siegel LS. Early identification and intervention to prevent reading failure: A response to Intervention (RTI) initiative. Educational and Developmental Psychologist. 2020; 37 (2):140–146. doi: 10.1017/edp.2020.21. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The Center for Public Integrity. (2021). When schools call police on kids. Retrieved June 21, 2022 from https://publicintegrity.org/education/criminalizing-kids/police-in-schools-disparities/

- Towers S, Gomez-Lievano A, Khan M, Mubayi A, Castillo-Chavez C. Contagion in mass killings and school shootings. PLoS One. 2015; 10 (7):e0117259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117259. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- U. S. Department of Education. (2021). An overview of exclusionary discipline practices in public schools for the 2017–18 school year . Civil Rights Data Collection. Retrieved June 21, 2022, from https://ocrdata.ed.gov/estimations/2017-2018

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights. (2020). 2017–18 civil rights data collection: The use of restraint and seclusion in children with disabilities in K-12 schools. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/restraint-and-seclusion.pdf

- U.S. General Accountability Office (2018). K-12 education: Discipline disparities for Black students, boys, and students with disabilities (GAO-18–258). Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-258

- Wan, W. (2019). Congressional deal could fund gun violence research for first time since 1990s. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 17, 2022 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/12/16/congressional-deal-could-fund-gun-violence-research-first-time-since-s/

- Wang, K., Chen, Y., Zhang, J., & Oudekerk, B. A. (2020). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2019 (NCES 2020–063/NCJ 254485). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020063-temp.pdf

- Washington Post. (2022). The Washington Post’s database of school shootings. Retrieved June 21, 2022 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/local/school-shootings-database/

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Next Article

US School Shootings, 1997–1998 Through 2021–2022

Us school mass shootings, 1997–1998 through 2021–2022, us school mass shootings, 1997–1998 through 2021–2022: fatalities and injuries, conclusions, school shootings in the united states: 1997–2022.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Luke J. Rapa , Antonis Katsiyannis , Samantha N. Scott , Olivia Durham; School Shootings in the United States: 1997–2022. Pediatrics April 2024; 153 (4): e2023064311. 10.1542/peds.2023-064311

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Video Abstract

Gun violence in the United States is a public health crisis. In 2019, gun injury became the leading cause of death among children aged birth to 19 years. Moreover, the United States has had 57 times as many school shootings as all other major industrialized nations combined. The purpose of this study was to understand the frequency of school-related gun violence across a quarter century, considering both school shootings and school mass shootings.

We drew on 2 publicly available datasets whose data allowed us to tabulate the frequency of school shootings and school mass shootings. The databases contain complementary data that provide a longitudinal, comprehensive view of school-related gun violence over the past quarter century.

Across the 1997–1998 to 2021–2022 school years, there were 1453 school shootings. The most recent 5 school years reflected a substantially higher number of school shootings than the prior 20 years. In contrast, US school mass shootings have not increased, although school mass shootings have become more deadly.

School shootings have risen in frequency in the recent 25 years and are now at their highest recorded levels. School mass shootings, although not necessarily increasing in frequency, have become more deadly. This leads to detrimental outcomes for all the nation’s youth, not just those who experience school-related gun violence firsthand. School-based interventions can be used to address this public health crisis, and effective approaches such as Multi-Tiered Systems of Supports and services should be used in support of students’ mental health and academic and behavioral needs.

Gun violence in the United States is a public health crisis. In 2019, gun injury became the leading cause of death among children aged birth-19 years. Similarly, school-related gun violence (eg, school shootings) has recently reached peak levels.

This study provides a longitudinal, comprehensive view of school-related gun violence over the past quarter century. Results reveal acceleration in school shootings in recent years, but not in school mass shootings; however, school mass shootings have become more deadly.

Gun violence in the United States is a public health crisis, with severe consequences for the nation’s youth. In 2019, gun injury became the leading cause of death among children aged birth to 19 years, surpassing vehicle-related deaths for the first time. 1 In 2020, the United States was the only country among its higher-income peers in which guns were the leading cause of death among children and adolescents. 2 , 3 In the 2021–2022 school year, the average number of gunfire incidents on school grounds had virtually quadrupled over the prior year, reaching an all-time high. 4 Likewise, during that same year, there were a total of 93 school shootings with casualties in elementary and secondary schools—more than in any other year since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began collecting such data. 5 In all, the United States has had 57 times as many school shootings as all other major industrialized nations combined. 6

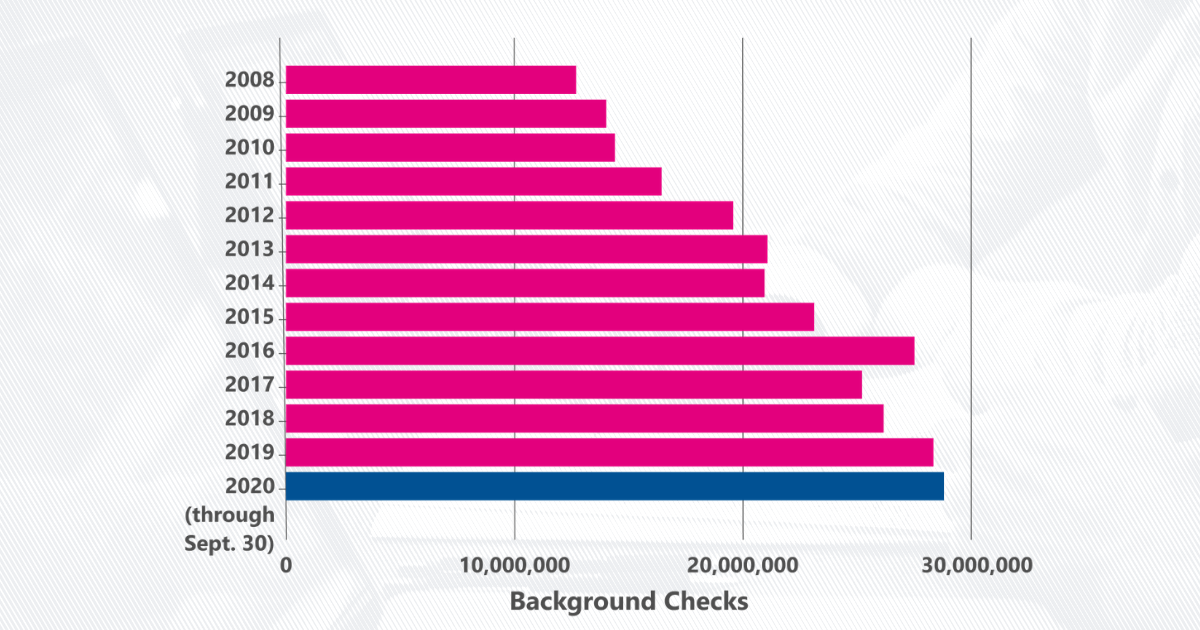

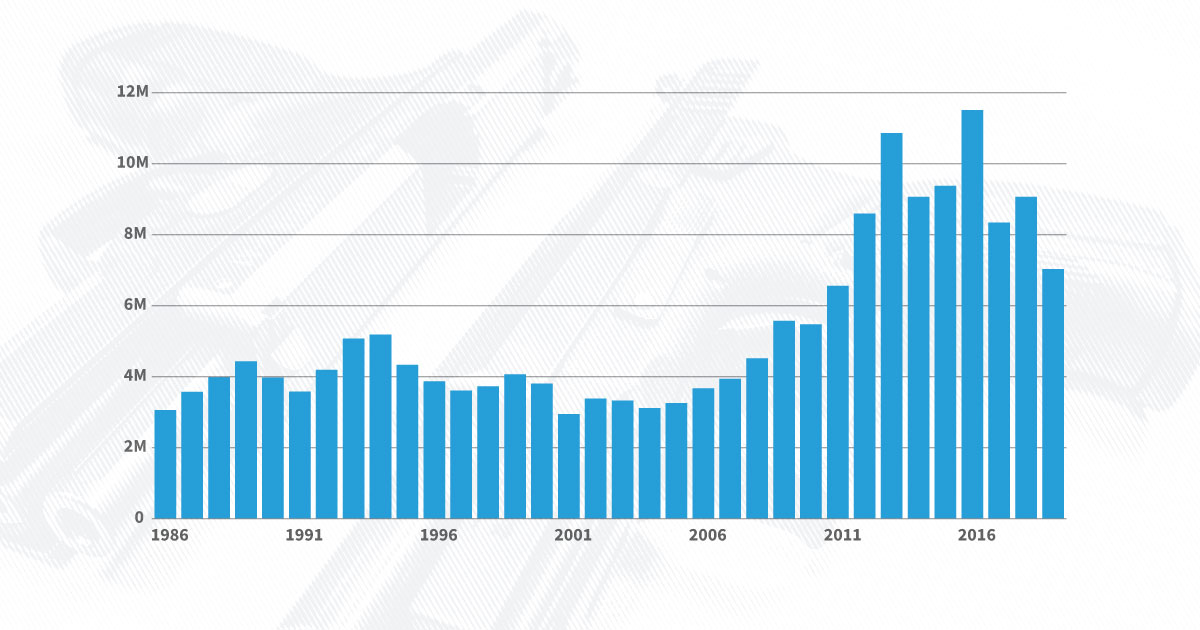

In addition to these dire statistics, gun purchases have recently reached an all-time high in the United States, with more than 22 million guns procured in 2022. 7 Stronger gun laws are linked with fewer deaths per capita, and recent empirical evidence suggests that states that instantiate more restrictive gun regulations have reduced gun deaths. 8 – 10 For example, child access protection legislation in 29 states and Washington, D.C., has resulted in a 22% decrease in firearm injuries per capita in those jurisdictions; notwithstanding, strong child access protection legislation has seen a 41% decrease in recent years. 11

Sadly, children’s exposure to gun violence in the United States, including gun violence associated with school shootings, has become commonplace over the past quarter century. The Columbine High School massacre that occurred in April 1999 heightened American discourse—and remains symbolically at the forefront of the American psyche—about school-related gun violence. Since that time, gun violence has come to typify schooling experiences of the nation’s youth. As such, the issue of gun violence in the United States, including school-related gun violence, demands continued attention, especially in terms of its effects on youth. Consequently, the purpose of this study was to assess school-related gun violence over the recent past 25-year period, starting approximately with the Columbine High School massacre. Specifically, we set out to examine school-related gun violence vis-à-vis kindergarten through grade 12 school shootings and school mass shootings across a recent 25-year period, 1997–1998 through 2021–2022. Our primary aim was to understand the frequency of school-related gun violence across the quarter century, from the 1997–1998 school year through the 2021–2022 school year, considering both school shootings and school mass shootings.

To accomplish the aim of our study, we drew on 2 publicly available datasets whose data would allow us to tabulate the frequency of school shootings and school mass shootings from the 1997–1998 school year through the 2021–2022 school year. The databases were selected because they contain complementary data that, when taken together, would provide a longitudinal, comprehensive view of school shootings and school mass shootings in the United States over the past quarter century. Data on school shootings were retrieved from the Center for Homeland Defense and Security’s School Shooting Safety Compendium. 12 Data on school mass shootings were retrieved from the US Mass Shootings, 1982–2023 database, developed by Mother Jones . 13 Two noteworthy challenges that exist when studying school shootings and school mass shootings are the lack of a central or unified database that contains all incidents of gun violence in the United States, and the varied definitions used, within disparate databases, for what constitutes respective datapoints—for example, what counts as a school shooting or a school mass shooting. 14 For the purposes of this study, we followed the definitions provided in each respective database for the outcome of interest. As such, in our study, a “school shooting” constituted “each and every instance a gun is brandished, is fired, or a bullet hits school property for any reason, regardless of the number of victims, time of day, or day of week”; incidents are cataloged in the database when they are noted in news reports published in print or online, and all specified incidents were included in our study. 12 Similarly, in our study, a “school mass shooting” was a shooting noted to have occurred at a kindergarten through 12th grade school site during which 3 or more victims were killed (shootings that occurred before January 2013 were counted if 4 or more victims were killed, pursuant to the operational definition of “mass shooting” that was in place at the time the database was initiated). 13 Again, all specified incidents in the database were included in our study. The analyses we conducted drew on incidents logged in each respective database in accord with these definitions. Data presented are holistic, as tabulated from each respective data source and calculated for each school year (which we denoted as July 1 through June 30). Results are presented descriptively.

Across the 1997–1998 to 2021–2022 school years, there were 1453 school shootings. The number of school shootings in the United States within a given school year has increased noticeably over the past 25 years, with the number of incidents per year initially appearing to be somewhat steady, then declining slightly, but then rising sharply in more recent years ( Fig 1 ). The number of school shootings in a given school year numbered between 15 and 328, with a low of 15 occurring during the 2009–2010 school year and a high of 328 occurring during the 2021–2022 school year. The most recent 5 school years reflected a substantially higher number of school shootings than the previous 20 years. Over the latest 5 school years—that is, across the 2017–2018 to the 2021–2022 school years—there were 794 school shootings. That was 135 more than the number of school shootings that occurred across the previous 15 school years combined ( n = 659).

US school shootings by school year, 1997–1998 through 2021–2022. School year denoted as July 1–June 30. Source: CHDS School Shooting Safety Compendium. Per the definition provided in the Compendium, a school shooting is defined as brandishing a gun, firing a gun, or a bullet hitting school property for any reason.

Although the number of US school shootings has substantially increased in recent years ( Fig 1 ), US school mass shootings have not increased in parallel ( Fig 2 ). There was a total of 11 school mass shootings across the 1997–1998 to 2021–2022 school years. A school mass shooting occurred in 8 of the 25 school year periods examined, with 2 school mass shootings occurring in 3 of the last 25 school year periods examined. There were 17 school years when no mass shooting occurred, whereas no more than 2 school mass shootings occurred during a given school year.

US school mass shootings by school year, 1997–1998 through 2021–2022. School year denoted as July 1–June 30. School mass shootings tabulated here are included in the school shooting counts reported in Fig 1 . Source: Mother Jones. 13

Across the 1997–1998 to 2021–2022 school years, a total of 122 people were killed and 126 were injured in the 11 school mass shootings that occurred, for a total of 248 victims ( Fig 3 ). On average then, over the 25-year time span examined, there were approximately 5 fatalities and 5 injuries per school year that could be attributed to school mass shootings. The greatest number of fatalities and injuries sustained from school mass shootings, combined, was in the 2017–2018 school year, with 27 fatalities and 30 injuries. The 2021–2022 school year had the second greatest number of fatalities and injuries sustained from school mass shootings, combined, with 25 fatalities and 24 injuries. The most recent 10 years had more fatalities and injuries ( n = 141) than the previous 15 years ( n = 107), with 34 more victims overall. As such, although the number of school mass shootings did not dramatically increase over the 25-year period spanning the 1997–1998 to 2021–2022 school years—in contrast to the number of school shootings more generally—school mass shootings became more deadly. For example, there were 7.6 fatalities per school mass shooting event ( n = 5) from 1997–1998 to 2011–2012, compared with 14 fatalities per school mass shooting event ( n = 6) from 2012–2013 to 2021–2022. Thus, the number of deaths per mass shooting event has effectually almost doubled when comparing the most recent school mass shooting events with those that occurred earlier.

US school mass shootings by school year: number of fatalities and number injured, 1997–1998 through 2021–2022. School year denoted as July 1–June 30. Source: Mother Jones. 13

Rates of gun violence in the United States continue to rise and, as a consequence, so do deaths resulting from that gun violence. 9 , 15 School shootings on the premises of U.S. kindergarten through twelfth grade schools are at their highest recorded levels. School-related gun violence and school mass shootings continue to be a serious public health concern, uniquely affecting youth within the United States. 16 In the discussion that follows, we draw on our findings and connect them to recent scholarship to consider the implications of increased school-related gun violence, including the psychological trauma that coincides with the rising prevalence of school shootings and the increased deadliness of school mass shootings in the United States.

The prevalence of school shootings and school mass shootings induces trauma in school-aged youth. Coping with the aftermath of violence—including school shootings and school mass shootings—is stressful and exacerbates that trauma. Children and adolescents directly exposed to violence and crime face a host of ancillary challenges, including drug and alcohol use and abuse, depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, school failure, and involvement in criminal activity. 4 , 17 – 19 Moreover, youth indirectly exposed are peripherally impacted through extensive media coverage of school shootings and school mass shootings; this leads to more people suffering the effects of these tragedies, with resultant outcomes tied to worsened mental health consequences among members of communities in which gun violence occurs. 18 , 20

Traumatic events—proximal or distal—affect youth’s development and well-being. Yet, schools often lack the financing for resources, student support programs, and personnel to provide students with optimal care. That is, schools sometimes struggle to meet the demands of students’ mental health needs even as the prevalence of school shootings increases and as the consequences of school mass shootings become more dire. 21 Successful school-based interventions and responses are possible, and they can lessen the probability of further trauma among youth impacted by gun violence. 22 Such interventions are needed in addition to broader policy changes and further restrictions in access to firearms. 16

After the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, President Obama promised to fund hundreds more school resource officers (SROs) and school-based mental health specialists across the nation. 23 In the wake of the Sandy Hook tragedy, more than 450 bills were introduced in state or federal legislatures with a focus on school safety. 9 , 24 , 25 To reduce violence and improve school safety, schools have relied increasingly on heightened security measures, including increased numbers of SROs and the implementation of zero-tolerance policies (including exclusionary and aversive measures). Despite their prevalence, however, research suggests that the presence of SROs has not decreased school shootings. 26 , 27 Similarly, though initially designed to reduce gun violence in schools, zero-tolerance policies have been broadened to cover a variety of incidents (eg, threats, bullying). Despite best intentions, these policies have generally failed to stop school shootings and other forms of violence. 28 , 29 Instead, such policies have increased the number of times students interact with law enforcement in and around schools.

Along with armed security, schools throughout the nation are teaching their students how to “run, hide, or fight” if approached by an active shooter. 16 During Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, and Evacuate drills, students are frequently exposed to unavoidable and frightening images and stories of school violence. 30 They are subject to active shooter drills that may not be effective and, in some cases, may themselves actually induce trauma. Simulation drills expose students to aggressive and frightening elements—for example, the use of fake blood, the shooting of guns loaded with blanks or rubber pellets, and the false pretense that it the occurrence is not a drill but an actual attack. 16 , 31 Despite the potential for induced fear, anxiety, and trauma to come from these drills, school administrators view these activities as a suitable response to parental demands to keep children safe. 16 , 32 Whatever benefit physical security, active shooter drills, and SROs may have in safeguarding students, imposing fortress-like settings on youth can increase fear and introduce trauma rather than reduce it. 16 , 33 , 34 In effect, the supports designed to keep students safe may be inadvertently doing harm to their mental health. To enhance efforts to support student safety, district and school leaders must aspire to implement discrete security measures to prevent gun violence and school shootings, for example, through environmental design. 16 , 35 , 36

Although security measures surely play an important role in protecting students from gun violence, it may be insufficient to focus only on shooting prevention through “hardening the target” 16 —that is by making school sites more secure to preemptively mitigate disaster. Prevention starts long before a shooter enters a school, and it includes more than just security measures on school premises. Instead, a comprehensive and scientifically supported public health approach is needed to address gun violence and school shootings. The Coalition of National Researchers proposed such an approach for safeguarding both children and adults against gun violence; the approach involves 3 levels of prevention: (1) universal approaches promoting safety and well-being for everyone; (2) practices for reducing risk and promoting protective factors for persons experiencing difficulties; and (3) interventions for individuals where violence is present or appears imminent. 37

Recently, the framework of Multi-Tiered Systems of Supports (MTSS)—including Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports and Response to Intervention—has been implemented in schools. 9 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 This evidence-based framework enables school personnel to address students’ educational, social, emotional, and behavioral needs. The Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports offers a wealth of resources and implementation strategies, and also provides information about data-driven decision-making, integration of evidence-based behavioral and academic interventions, preventive measures, culturally sensitive practices, and mental health support. 41 , 42 Schools should consider the implementation of MTSS as a means to counter the threat of gun violence, school shootings, and school mass shootings because it reduces reliance on exclusionary and aversive measures like zero-tolerance policies, seclusion and restraints, corporal punishment, and school-based law enforcement referrals and arrests. Instead, MTSS engenders support for students’ well-being, improves school climate, and supports reductions in behavioral issues and school violence. 9 , 43

This study, like any empirical inquiry, has some limitations that should be considered as its results are interpreted. First, the databases used for this study were compiled directly from news reports and other publicly available or publicly reported information. Although the authors of each respective database have endeavored to do their due diligence to verify the accuracy of the data compiled in their database, because of reliance on public reporting, there is certainly the potential for undercounting the number of school-related gun violence incidents that occurred each year. As media attention on gun violence has increased over the years, there is also the potential for the number of reported incidents each year to be higher, such that incidents overall may not have increased or be increasing, but rather the observed increases may be an artifact of more attention paid to this issue by news media in more recent years. Given the similar national trends in gun violence and gun-related deaths, however, this explanation seems unlikely. 15 , 44

The analyses in this study were also limited by and linked to the definitions of school shootings and school mass shootings as delineated in the databases from which we drew for the study’s data. This naturally constrained our ability to consider these outcomes from vantage points that are either beyond the scope or different in scope from those advanced by and reported in each respective database. 14 There is no singular national database that contains all pertinent information and complete statistics on school shootings and school mass shootings. This limits researchers’ ability to conduct empirical analyses on school shootings and school mass shootings.

These limitations notwithstanding, the analyses we conducted did provide new insights into the issue of school shootings and school mass shootings across a recent 25-year span, school years 1997–1998 through 2021–2022. Rates of school shootings have increased, and school mass shootings have become more deadly. In light of these results, we considered the effects of these increasing rates and risks associated with school-related gun violence for the nation’s youth, who have spent their entire lives attending schools marked by the specter of school shootings and school mass shootings.

Gun violence in United States is a public health crisis affecting the nation’s youth. School shootings have risen in frequency in the recent 25 years, and they are now at their highest recorded levels. School mass shootings, while they have not necessarily increased in frequency, have become more deadly. This public health crisis leads to detrimental outcomes for all the nation’s youth—not just those who experience school-related gun violence firsthand. School-based interventions can be used to address this public health crisis, and effective approaches such as MTSS and services should be used in support of students’ mental health and academic and behavioral needs.

Drs Rapa and Katsiyannis conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to analyses, drafted portions of the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Scott and Ms Durham drafted portions of the initial manuscript and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2023-065281 .

FUNDING: No external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Multi-Tiered Systems of Supports

school resource officer

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Sorry, we did not find any matching results.

We frequently add data and we're interested in what would be useful to people. If you have a specific recommendation, you can reach us at [email protected] .

We are in the process of adding data at the state and local level. Sign up on our mailing list here to be the first to know when it is available.

Search tips:

• Check your spelling

• Try other search terms

• Use fewer words

The latest government data on school shootings

The 2021–22 school year had the highest number of school shootings since records began in 2000.

Updated on Tue, February 20, 2024 by the USAFacts Team

In the wake of the school shooting at Perry High School in Perry, Iowa, USAFacts has collected recent data about school shootings in the United States. Here’s what current data has to say about these incidents.

The Center for Homeland Defense and Security maintains a collection of metrics on school shootings: the K–12 School Shooting Database (or K–12 SSDB) .

How many people have died in school shootings?

From the 2000–01 to 2021–22 school years, there were 1,375 school shootings at public and private elementary and secondary schools, resulting in 515 deaths and 1,161 injuries.

School shootings, defined

The definition of a school shooting is provided by the School Shooting Safety Compendium (SSSC) from the Center for Homeland Defense and Security. The SSSC defines “school shootings” as incidents in which “a gun is brandished, is fired, or a bullet hits school property for any reason, regardless of the number of victims, time of day, or day of week.” During the coronavirus pandemic, this definition included shootings that happened on school property during remote instruction.

The highest number of school shootings and casualties occurred during the 2021–22 school year, with 327 incidences resulting in 81 deaths and 269 injuries.

Between the 2000–01 and the 2021–22 school years, 70.8% of the 1,375 school shootings resulted in deaths or injuries.

Approximately 61.0% of recorded school shootings occurred at high schools, followed by 23.6% at elementary schools, 12.0% at middle or junior high schools, and 3.4% at other educational institutions. [1] School shootings at college-level institutions are not included in this dataset.

Where do school shootings occur most often?

The most common spot for a school shooting was the parking lot, accounting for 28.3% of recorded cases, followed by any area directly outside the front or side entrances of the school (20.4%), and then “elsewhere inside of the school building,” meaning any area outside from the classroom, hallways, or basketball court (12.5%).

Where does this data come from?

The K-12 SSDB aims to compile information on school shootings from publicly available sources into a single comprehensive database. It defines school shootings as situations when someone brandishes or fires a gun on school property or a bullet hits school property for any reason, regardless of the number of victims, time or day of the week, or motivation.

For a fuller picture of crime in the US , read about how many high schoolers in the US carry guns , and get more USAFacts data in your inbox by subscribing to our weekly newsletter .

Includes schools for which school-level information was unknown or unspecified as well as those whose school level was "other."

Explore more of USAFacts

Related articles, the federal data available on active shooter incidents, mass killings and domestic terrorism.

2020 has been a record-setting year for background checks, but other firearm data is incomplete

How many guns are made in the US?

Firearm background checks: Explained

Related Data

Public School Staff

6.63 million

Firearm Deaths in the US: Statistics and Trends

Data delivered to your inbox.

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

SIGN UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER

School shootings: What we know about them, and what we can do to prevent them

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, robin m. kowalski, ph.d. robin m. kowalski, ph.d. professor, department of psychology - clemson university @cuprof.

January 26, 2022

On the morning of Nov. 30, 2021, a 15-year-old fatally shot four students and injured seven others at his high school in Oakland County, Michigan. It’s just one of the latest tragedies in a long line of the horrific K-12 school shootings now seared into our memories as Americans.

And we have seen that the threat of school shootings, in itself, is enough to severely disrupt schools. In December, a TikTok challenge known as “ National Shoot Up Your School Day ” gained prominence. Although vague and with no clear origin, the challenge warned of possible acts of violence at K-12 schools. In response, some schools nationwide cancelled classes, others stepped up security. Many students stayed home from school that day. (It’s worth noting that no incidents of mass violence ended up occurring.)

What are the problems that appear to underlie school shootings? How can we better respond to students that are in need? If a student does pose a threat and has the means to carry it out, how can members of the school community act to stop it? Getting a better grasp of school shootings, as challenging as it might be, is a clear priority for preventing harm and disruption for kids, staff, and families. This post considers what we know about K-12 school shootings and what we might do going forward to alleviate their harms.

Who is perpetrating school shootings?

As the National Association of School Psychologists says, “There is NO profile of a student who will cause harm.” Indeed, any attempt to develop profiles of school shooters is an ill-advised and potentially dangerous strategy. Profiling risks wrongly including many children who would never consider committing a violent act and wrongly excluding some children who might. However, while an overemphasis on personal warning signs is problematic, there can still be value in identifying certain commonalities behind school shootings. These highlight problems that can be addressed to minimize the occurrence of school shootings, and they can play a pivotal role in helping the school community know when to check in—either with an individual directly or with someone close to them (such as a parent or guidance counselor). Carefully integrating this approach into a broader prevention strategy helps school personnel understand the roots of violent school incidents and assess risks in a way that avoids the recklessness of profiling.

Within this framework of threat assessment, exploring similarities and differences of school shootings—if done responsibly—can be useful to prevention efforts. To that end, I recently published a study with colleagues that examined the extent to which features common to school shootings prior to 2003 were still relevant today. We compared the antecedents of K-12 shootings, college/university shootings, and other mass shootings.