Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

Published on May 8, 2020 by Lauren Thomas . Revised on June 22, 2023.

In a longitudinal study, researchers repeatedly examine the same individuals to detect any changes that might occur over a period of time.

Longitudinal studies are a type of correlational research in which researchers observe and collect data on a number of variables without trying to influence those variables.

While they are most commonly used in medicine, economics, and epidemiology, longitudinal studies can also be found in the other social or medical sciences.

Table of contents

How long is a longitudinal study, longitudinal vs cross-sectional studies, how to perform a longitudinal study, advantages and disadvantages of longitudinal studies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about longitudinal studies.

No set amount of time is required for a longitudinal study, so long as the participants are repeatedly observed. They can range from as short as a few weeks to as long as several decades. However, they usually last at least a year, oftentimes several.

One of the longest longitudinal studies, the Harvard Study of Adult Development , has been collecting data on the physical and mental health of a group of Boston men for over 80 years!

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

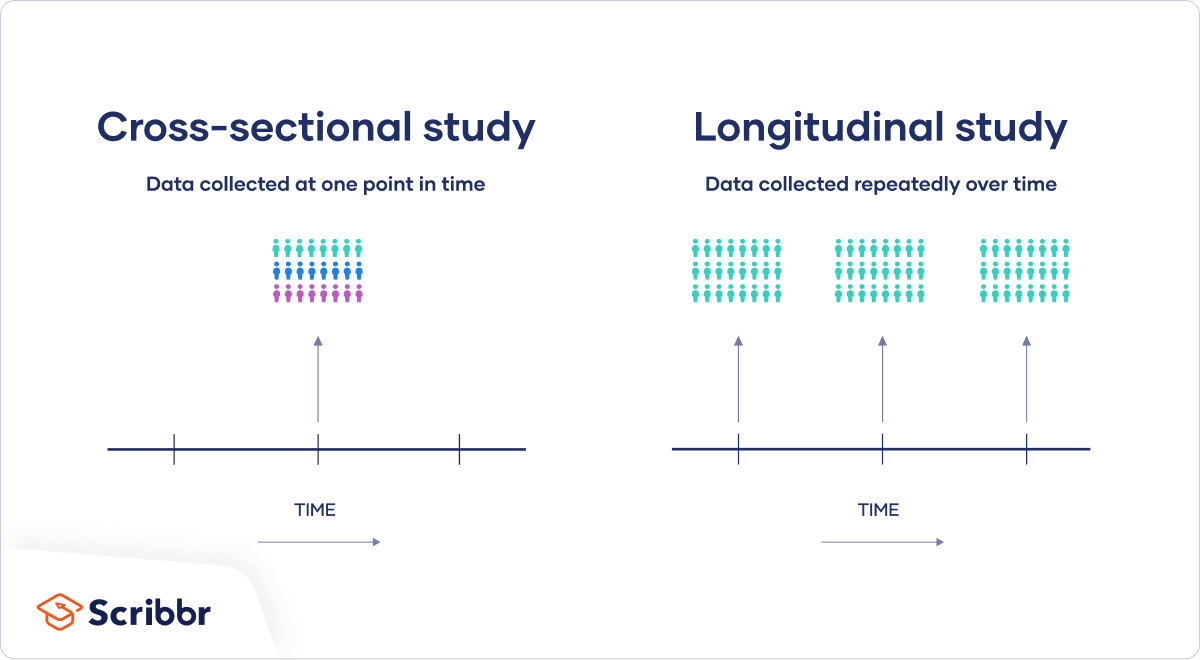

The opposite of a longitudinal study is a cross-sectional study. While longitudinal studies repeatedly observe the same participants over a period of time, cross-sectional studies examine different samples (or a “cross-section”) of the population at one point in time. They can be used to provide a snapshot of a group or society at a specific moment.

Both types of study can prove useful in research. Because cross-sectional studies are shorter and therefore cheaper to carry out, they can be used to discover correlations that can then be investigated in a longitudinal study.

If you want to implement a longitudinal study, you have two choices: collecting your own data or using data already gathered by somebody else.

Using data from other sources

Many governments or research centers carry out longitudinal studies and make the data freely available to the general public. For example, anyone can access data from the 1970 British Cohort Study, which has followed the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in a single week in 1970, through the UK Data Service website .

These statistics are generally very trustworthy and allow you to investigate changes over a long period of time. However, they are more restrictive than data you collect yourself. To preserve the anonymity of the participants, the data collected is often aggregated so that it can only be analyzed on a regional level. You will also be restricted to whichever variables the original researchers decided to investigate.

If you choose to go this route, you should carefully examine the source of the dataset as well as what data is available to you.

Collecting your own data

If you choose to collect your own data, the way you go about it will be determined by the type of longitudinal study you choose to perform. You can choose to conduct a retrospective or a prospective study.

- In a retrospective study , you collect data on events that have already happened.

- In a prospective study , you choose a group of subjects and follow them over time, collecting data in real time.

Retrospective studies are generally less expensive and take less time than prospective studies, but are more prone to measurement error.

Like any other research design , longitudinal studies have their tradeoffs: they provide a unique set of benefits, but also come with some downsides.

Longitudinal studies allow researchers to follow their subjects in real time. This means you can better establish the real sequence of events, allowing you insight into cause-and-effect relationships.

Longitudinal studies also allow repeated observations of the same individual over time. This means any changes in the outcome variable cannot be attributed to differences between individuals.

Prospective longitudinal studies eliminate the risk of recall bias , or the inability to correctly recall past events.

Disadvantages

Longitudinal studies are time-consuming and often more expensive than other types of studies, so they require significant commitment and resources to be effective.

Since longitudinal studies repeatedly observe subjects over a period of time, any potential insights from the study can take a while to be discovered.

Attrition, which occurs when participants drop out of a study, is common in longitudinal studies and may result in invalid conclusions.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different types of research design . In a cross-sectional study you collect data from a population at a specific point in time; in a longitudinal study you repeatedly collect data from the same sample over an extended period of time.

| Longitudinal study | Cross-sectional study |

|---|---|

| observations | Observations at a in time |

| Observes the multiple times | Observes (a “cross-section”) in the population |

| Follows in participants over time | Provides of society at a given point |

Longitudinal studies can last anywhere from weeks to decades, although they tend to be at least a year long.

Longitudinal studies are better to establish the correct sequence of events, identify changes over time, and provide insight into cause-and-effect relationships, but they also tend to be more expensive and time-consuming than other types of studies.

The 1970 British Cohort Study , which has collected data on the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in 1970, is one well-known example of a longitudinal study .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Thomas, L. (2023, June 22). Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved October 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/longitudinal-study/

Is this article helpful?

Lauren Thomas

Other students also liked, cross-sectional study | definition, uses & examples, correlational research | when & how to use, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Longitudinal studies

Edward joseph caruana, marius roman, jules hernández-sánchez, piergiorgio solli.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to: Piergiorgio Solli. Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Papworth Everard Cambridgeshire, CB23 3RE, UK. Email: [email protected] .

Corresponding author.

Received 2015 Sep 19; Accepted 2015 Oct 9; Issue date 2015 Nov.

Introduction

Longitudinal studies employ continuous or repeated measures to follow particular individuals over prolonged periods of time—often years or decades. They are generally observational in nature, with quantitative and/or qualitative data being collected on any combination of exposures and outcomes, without any external influenced being applied. This study type is particularly useful for evaluating the relationship between risk factors and the development of disease, and the outcomes of treatments over different lengths of time. Similarly, because data is collected for given individuals within a predefined group, appropriate statistical testing may be employed to analyse change over time for the group as a whole, or for particular individuals ( 1 ).

In contrast, cross-sectional analysis is another study type that may analyse multiple variables at a given instance, but provides no information with regards to the influence of time on the variables measured—being static by its very nature. It is thus generally less valid for examining cause-and-effect relationships. Nonetheless, cross-sectional studies require less time to be set up, and may be considered for preliminary evaluations of association prior to embarking on cumbersome longitudinal-type studies.

Longitudinal study designs

Longitudinal research may take numerous different forms. They are generally observational, however, may also be experimental. Some of these are briefly discussed below:

Repeated cross-sectional studies where study participants are largely or entirely different on each sampling occasion;

Prospective studies where the same participants are followed over a period of time. These may include:

Cohort panels wherein some or all individuals in a defined population with similar exposures or outcomes are considered over time;

Representative panels where data is regularly collected for a random sample of a population;

Linked panels wherein data collected for other purposes is tapped and linked to form individual-specific datasets.

Retrospective studies are designed after at least some participants have already experienced events that are of relevance; with data for potential exposures in the identified cohort being collected and examined retrospectively.

Advantages and disadvantages

Longitudinal cohort studies, particularly when conducted prospectively in their pure form, offer numerous benefits. These include:

The ability to identify and relate events to particular exposures, and to further define these exposures with regards to presence, timing and chronicity;

Establishing sequence of events;

Following change over time in particular individuals within the cohort;

Excluding recall bias in participants, by collecting data prospectively and prior to knowledge of a possible subsequent event occurring, and;

Ability to correct for the “cohort effect”—that is allowing for analysis of the individual time components of cohort (range of birth dates), period (current time), and age (at point of measurement)—and to account for the impact of each individually.

Disadvantages

Numerous challenges are implicit in the study design; particularly by virtue of this occurring over protracted time periods. We briefly consider the below:

Incomplete and interrupted follow-up of individuals, and attrition with loss to follow-up over time; with notable threats to the representative nature of the dynamic sample if potentially resulting from a particular exposure or occurrence that is of relevance;

Difficulty in separation of the reciprocal impact of exposure and outcome, in view of the potentiation of one by the other; and particularly wherein the induction period between exposure and occurrence is prolonged;

The potential for inaccuracy in conclusion if adopting statistical techniques that fail to account for the intra-individual correlation of measures, and;

Generally-increased temporal and financial demands associated with this approach.

Embarking on a longitudinal study

Conducting longitudinal research is demanding in that it requires an appropriate infrastructure that is sufficiently robust to withstand the test of time, for the actual duration of the study. It is essential that the methods of data collection and recording are identical across the various study sites, as well as being standardised and consistent over time. Data must be classified according to the interval of measure, with all information pertaining to particular individuals also being linked by means of unique coding systems. Recording is facilitated, and accuracy increased, by adopting recognised classification systems for individual inputs ( 2 ).

Numerous variables are to be considered, and adequately controlled, when embarking on such a project. These include factors related the population being studied, and their environment; wherein stability in terms of geographical mobility and distribution, coupled with an ability to continue follow-up remotely in case of displacement, are key. It is furthermore essential to appropriately weigh the various measures, and classify these accordingly so as to facilitate the allocation effort at the data collection stage, and also guide the use of possibly limited funds ( 3 ). Additionally, the engagement and commitment of organisations contributing to the project is essential; and should be maintained and facilitated by means of regular training, communication and inclusion as possible.

The frequency and degree of sampling should vary according to the specific primary endpoints; and whether these are based primarily on absolute outcome or variation over time. Ethical and consent considerations are also specific to this type of research. All effort should be made to ensure maximal retention of participants; with exit interviews offering useful insight as to the reason for uncontrolled departures ( 3 ).

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) ( 4 ) offers a series of tools and checklists that are designed to facilitate the evaluation of scientific quality of given literature. This may be extrapolated to critically assess a proposed study design. Additional depth of quality assessment is available through the use of various tools developed alongside the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines, including a structured 33-point checklist proposed by Tooth et al . in 2004 ( 5 ).

Following adequate design, the launch and implementation of longitudinal research projects may itself require a significant amount of time; particularly if being conducted at multiple remote sites. Time invested in this initial period will improve the accuracy of data eventually received, and contribute to the validity of the results. Regular monitoring of outcome measures, and focused review of any areas of concern is essential ( 3 ). These studies are dynamic, and necessitate regular updating of procedures and retraining of contributors, as dictated by events.

Statistical analyses

The statistical testing of longitudinal data necessitates the consideration of numerous factors. Central amongst these are (I) the linked nature of the data for an individual, despite separation in time; (II) the co-existence of fixed and dynamic variables; (III) potential for differences in time intervals between data instances, and (IV) the likely presence of missing data ( 6 ).

Commonly applied approaches ( 7 ) are discussed below: (I) univariate (ANOVA) and multivariate (MANOVA) analysis of variance is often adopted for longitudinal analysis. Note, in both cases, the assumption of equal interval lengths and normal distribution in all groups; and that only means are compared, sacrificing individual-specific data. (II) mixed-effect regression model (MRM) focuses specifically on individual change over time, whilst accounting for variation in the timing of repeated measures, and for missing or unequal data instances, and (III) generalised estimating equation (GEE) models that rely on the independence of individuals within the population to focus primarily on regression data ( 6 ).

With ever-growing computational abilities, the repertoire of statistical tests is ever expanding. In depth understanding and appropriate selection is increasingly more important to ensure meaningful results.

Common errors

Inaccuracies in the analysis of longitudinal research are rampant, and most commonly arise when repeated hypothesis testing is applied to the data, as it would for cross-sectional studies. This leads to an underutilisation of available data, an underestimation of variability, and an increased likelihood of type II statistical error (false negative) ( 8 ).

Example: the Framingham heart study

The mid-20 th century saw a steady increase in cardiovascular-associated morbidity and mortality after efforts in improving sanitation along with the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s resulted in a significant decline in communicable disease. A drive to identify the risk factors for cardiovascular disease gave birth to the Framingham Heart study in 1948 ( 9 ).

Numerous predisposing factors were postulated to align together to produce cardiovascular disease, with increasing age being considered a central determinant. These formed the basis for the hypothesis that underpinned this longitudinal study.

The Framingham study is widely recognised as the quintessential longitudinal study in the history of medical research. An original cohort of 5,209 subjects from Framingham, Massachusetts between the ages of 30 and 62 years of age was recruited and followed up for 20 years. A number of hypothesis were generated and described by Dawber et al . ( 10 ) in 1980 listing various presupposed risk factors such as increasing age, increased weight, tobacco smoking, elevated blood pressure, elevated blood cholesterol and decreased physical activity. It is largely quoted as a successful longitudinal study owing to the fact that a large proportion of the exposures chosen for analysis were indeed found to correlate closely with the development of cardiovascular disease.

A number of biases exist within the Framingham Heart Study. Firstly it was a study carried out in a single population in a single town, bringing into question the generalisability and applicability of this data to different groups. However, Framingham was sufficiently diverse both in ethnicity and socio-economic status to mitigate this bias to a degree. Despite the initial intent of random selection, they needed the addition of over 800 volunteers to reach the pre-defined target of 5,000 subjects thus reducing the randomisation. They also found that their cohort of patients was uncharacteristically healthy.

The Framingham Heart study has given us invaluable data pertaining to the incidence of cardiovascular disease and further confirming a number of risk factors. The success of this study was further potentiated by the absence of treatments or modifiers, such as statin therapy and anti-hypertensives. This has enabled this study to more clearly delineate the natural history of this complex disease process.

Conclusions

Longitudinal methods may provide a more comprehensive approach to research, that allows an understanding of the degree and direction of change over time. One should carefully consider the cost and time implications of embarking on such a project, whilst ensuring complete and proven clarity in design and process, particularly in view of the protracted nature of such an endeavour; and noting the peculiarities for consideration at the interpretation stage.

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

- 1. Van Belle G, Fisher L, Heagerty PJ, et al. Biostatistics: A Methodology for the Health Sciences. Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. van Weel C. Longitudinal research and data collection in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2005;3 Suppl 1:S46-51. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Newman AB. An overview of the design, implementation, and analyses of longitudinal studies on aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58 Suppl 2:S287-91. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. 12 questions to help you make sense of cohort study. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Cohort Study Checklist. Available online: http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_e37a4ab637fe46a0869f9f977dacf134.pdf

- 5. Tooth L, Ware R, Bain C, et al. Quality of reporting of observational longitudinal research. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:280-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Edwards LJ. Modern statistical techniques for the analysis of longitudinal data in biomedical research. Pediatr Pulmonol 2000;30:330-44. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Nakai M, Ke W. Statistical Models for Longitudinal Data Analysis. Applied Mathematical Sciences 2009; 3:1979-89 [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Liu C, Cripe TP, Kim MO. Statistical issues in longitudinal data analysis for treatment efficacy studies in the biomedical sciences. Mol Ther 2010;18:1724-30. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Dawber TR, Kannel WB, Lyell LP. An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: the Framingham Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1963;107:539-56. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Dawber TR. The Framingham Study: The Epidemiology of Atherosclerotic Disease. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1980. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (113.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

What (Exactly) Is A Longitudinal Study?

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | June 2020

I f you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably feeling a bit overwhelmed by all the technical lingo that’s hitting you. If you’ve landed here, chances are one of these terms is “longitudinal study”, “longitudinal survey” or “longitudinal research”.

Worry not – in this post, we’ll explain exactly:

- What a longitudinal study is (and what the alternative is)

- What the main advantages of a longitudinal study are

- What the main disadvantages of a longitudinal study are

- Whether to use a longitudinal or cross-sectional study for your research

What is a longitudinal study?

A longitudinal study or a longitudinal survey (both of which make up longitudinal research) is a study where the same data are collected more than once, at different points in time . The purpose of a longitudinal study is to assess not just what the data reveal at a fixed point in time, but to understand how (and why) things change over time.

The opposite of a longitudinal study is a cross-sectional study , which is a design where you only collect data at one point in time.

Example: Longitudinal vs Cross-Sectional

Here are two examples – one of a longitudinal study and one of a cross-sectional study – to give you an idea of what these two approaches look like in the real world:

Longitudinal study: a study which assesses how a group of 13-year old children’s attitudes and perspectives towards income inequality evolve over a period of 5 years, with the same group of children surveyed each year, from 2020 (when they are all 13) until 2025 (when they are all 18).

Cross-sectional study: a study which assesses a group of teenagers’ attitudes and perspectives towards income equality at a single point in time. The teenagers are aged 13-18 years and the survey is undertaken in January 2020.

Additionally, in the cross-sectional group, each age group (i.e. 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18) are all different people (obviously!) with different life experiences – whereas, in the longitudinal group, each the data at each age point is generated by the same group of people (for example, John Doe will complete a survey at age 13, 14, 15, and so on).

What are the advantages of a longitudinal study?

Longitudinal studies and longitudinal surveys offer some major benefits over cross-sectional studies. Some of the main advantages are:

Patterns – because longitudinal studies involve collecting data at multiple points in time from the same respondents, they allow you to identify emergent patterns across time that you’d never see if you used a cross-sectional approach.

Order – longitudinal studies reveal the order in which things happened, which helps a lot when you’re trying to understand causation. For example, if you’re trying to understand whether X causes Y or Y causes X, it’s essential to understand which one comes first (which a cross-sectional study cannot tell you).

Bias – because longitudinal studies capture current data at multiple points in time, they are at lower risk of recall bias . In other words, there’s a lower chance that people will forget an event, or forget certain details about it, as they are only being asked to discuss current matters.

Need a helping hand?

What are the disadvantages of a longitudinal study?

As you’ve seen, longitudinal studies have some major strengths over cross-sectional studies. So why don’t we just use longitudinal studies for everything? Well, there are (naturally) some disadvantages to longitudinal studies as well.

Cost – compared to cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies are typically substantially more expensive to execute, as they require maintained effort over a long period of time.

Slow – given the nature of a longitudinal study, it takes a lot longer to pull off than a cross-sectional study. This can be months, years or even decades. This makes them impractical for many types of research, especially dissertations and theses at Honours and Masters levels (where students have a predetermined timeline for their research)

Drop out – because longitudinal studies often take place over many years, there is a very real risk that respondents drop out over the length of the study. This can happen for any number of reasons (for examples, people relocating, starting a family, a new job, etc) and can have a very detrimental effect on the study.

Which one should you use?

Choosing whether to use a longitudinal or cross-sectional study for your dissertation, thesis or research project requires a few considerations. Ultimately, your decision needs to be informed by your overall research aims, objectives and research questions (in other words, the nature of the research determines which approach you should use). But you also need to consider the practicalities. You should ask yourself the following:

- Do you really need a view of how data changes over time, or is a snapshot sufficient?

- Is your university flexible in terms of the timeline for your research?

- Do you have the budget and resources to undertake multiple surveys over time?

- Are you certain you’ll be able to secure respondents over a long period of time?

If your answer to any of these is no, you need to think carefully about the viability of a longitudinal study in your situation. Depending on your research objectives, a cross-sectional design might do the trick. If you’re unsure, speak to your research supervisor or connect with one of our friendly Grad Coaches .

Learn More About Methodology

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

5 Signs You Need A Dissertation Helper

Discover the 5 signs that suggest you need a dissertation helper to get unstuck, finish your degree and get your life back.

Triangulation: The Ultimate Credibility Enhancer

Triangulation is one of the best ways to enhance the credibility of your research. Learn about the different options here.

Research Limitations 101: What You Need To Know

Learn everything you need to know about research limitations (AKA limitations of the study). Includes practical examples from real studies.

In Vivo Coding 101: Full Explainer With Examples

Learn about in vivo coding, a popular qualitative coding technique ideal for studies where the nuances of language are central to the aims.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > The Cambridge Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology

- > Designing and Managing Longitudinal Studies

Book contents

- The Cambridge Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology

- Copyright page

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Clinical Psychological Science

- Part II Observational Approaches

- Part III Experimental and Biological Approaches

- Part IV Developmental Psychopathology and Longitudinal Methods

- 15 Studying Psychopathology in Early Life

- 16 Adolescence and Puberty

- 17 Quantitative Genetic Research Strategies for Studying Gene-Environment Interplay in the Development of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology

- 18 Designing and Managing Longitudinal Studies

- 19 Measurement and Comorbidity Models for Longitudinal Data

- Part V Intervention Approaches

- Part VI Intensive Longitudinal Designs

- Part VII General Analytic Considerations

18 - Designing and Managing Longitudinal Studies

from Part IV - Developmental Psychopathology and Longitudinal Methods

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 March 2020

This chapter outlines critical design decisions for longitudinal research and provides practical tips for managing such studies. It emphasizes that generative longitudinal studies are driven by conceptual and theoretical insights and describes four foundational design issues including questions about time lags and sample sizes. It then provides advice about how to manage a longitudinal study and reduce attrition. The chapter concludes by considering how the advice offered comports with recent discussions about ways to improve psychological science and providing recommended further reading.

Access options

Recommended reading.

Block’s chapter provides an insider perspective on longitudinal studies of personality and offers nine desiderata for studies.

This paper summarizes the thorny issues involved in selecting time lags for longitudinal studies.

Although it is over 25 years old, this piece provides practical advice and tips for running a large-scale longitudinal study. The advice holds for many less expansive designs as well.

This article offers a wealth of advice about reducing attrition beyond what was covered in this chapter.

Transparency and an awareness of researcher degrees of freedom are helpful for all kinds of psychological research. The guidelines in this article seem especially relevant when analyzing data from existing longitudinal studies.

This work provides an overview of the kinds of choices facing researchers and the checklist may increase awareness of p-hacking and improve the rigor of longitudinal analyses.

Save book to Kindle

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Designing and Managing Longitudinal Studies

- By M. Brent Donnellan , Deborah A. Kashy

- Edited by Aidan G. C. Wright , University of Pittsburgh , Michael N. Hallquist , Pennsylvania State University

- Book: The Cambridge Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology

- Online publication: 23 March 2020

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316995808.022

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The purpose of this article is to present cutting-edge research on issues relating to the theory, design, and analysis of change. Rather than a highly technical review, our goal is to provide ...

Longitudinal studies are a type of correlational research in which researchers observe and collect data on a number of variables without trying to influence those variables. While they are most commonly used in medicine, economics, and epidemiology, longitudinal studies can also be found in the other social or medical sciences.

Longitudinal cohort studies, particularly when conducted prospectively in their pure form, offer numerous benefits. These include: The ability to identify and relate events to particular exposures, and to further define these exposures with regards to presence, timing and chronicity;

Longitudinal study: a study which assesses how a group of 13-year old children’s attitudes and perspectives towards income inequality evolve over a period of 5 years, with the same group of children surveyed each year, from 2020 (when they are all 13) until 2025 (when they are all 18).

This study attempts to address the lack of comprehensive knowledge linking various characteristics to the degree of attrition across longitudinal aging studies. While it has become common practice to address attrition effects in individual research, few studies have sought to define the dimensions and characteristics of attrition. Moreover, to

The purpose of this article is to present cutting-edge research on issues relating to the theory, design, and analysis of change. Rather than a highly technical review, our goal is to provide management scholars with a relatively nontechnical single source useful for helping them develop and evaluate longitudinal research.

It emphasizes that generative longitudinal studies are driven by conceptual and theoretical insights and describes four foundational design issues including questions about time lags and sample sizes. It then provides advice about how to manage a longitudinal study and reduce attrition.

Longitudinal studies are observational studies used to measure the outcomes of an exposure over a period of time and determine if outcomes vary in time. These studies can be retrospective or prospective.

Objective: In this review article, we present an overview of the results of longitudinal studies on the consequences of job insecurity for health and well-being. We discuss the evidence for normal causation (“Does job insecurity influence outcomes?”), reversed causation (“Do specific outcomes predict job insecurity?”), and reciprocal ...

This handbook offers resources to investigators for conducting longitudinal studies. Recommended readings: Hay, D. F., Paine, A. L., Perra, O., Cook, K. V., Hashmi, S., Robinson, C., Kairis, V., & Slade, R. (2021).