An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence

Annamaria lusardi, olivia s mitchell.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

This paper undertakes an assessment of a rapidly growing body of economic research on financial literacy. We start with an overview of theoretical research which casts financial knowledge as a form of investment in human capital. Endogenizing financial knowledge has important implications for welfare as well as policies intended to enhance levels of financial knowledge in the larger population. Next, we draw on recent surveys to establish how much (or how little) people know and identify the least financially savvy population subgroups. This is followed by an examination of the impact of financial literacy on economic decision-making in the United States and elsewhere. While the literature is still young, conclusions may be drawn about the effects and consequences of financial illiteracy and what works to remedy these gaps. A final section offers thoughts on what remains to be learned if researchers are to better inform theoretical and empirical models as well as public policy.

1. Introduction

Financial markets around the world have become increasingly accessible to the ‘small investor,’ as new products and financial services grow widespread. At the onset of the recent financial crisis, consumer credit and mortgage borrowing had burgeoned. People who had credit cards or subprime mortgages were in the historically unusual position of being able to decide how much they wanted to borrow. Alternative financial services, including payday loans, pawn shops, auto title loans, tax refund loans, and rent-to-own shops have also become widespread. 1 At the same time, changes in the pension landscape are increasingly thrusting responsibility for saving, investing, and decumulating wealth onto workers and retirees, whereas in the past, older workers relied mainly on Social Security and employer-sponsored defined benefit (DB) pension plans in retirement. Today, by contrast, Baby Boomers mainly have defined contribution (DC) plans and Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) during their working years. This trend toward disintermediation increasingly is requiring people to decide how much to save and where to invest, and during retirement, to take on responsibility for careful decumulation so as not to outlive their assets while meeting their needs. 2

Despite the rapid spread of such financially complex products to the retail marketplace, including student loans, mortgages, credit cards, pension accounts, and annuities, many of these have proven to be difficult for financially unsophisticated investors to master. 3 Therefore, while these developments have their advantages, they also impose on households a much greater responsibility to borrow, save, invest, and decumulate their assets sensibly by permitting tailored financial contracts and more people to access credit. Accordingly, one goal of this paper is to offer an assessment of how well-equipped today’s households are to make these complex financial decisions. Specifically we focus on financial literacy , by which we mean peoples’ ability to process economic information and make informed decisions about financial planning, wealth accumulation, debt, and pensions. In what follows, we outline recent theoretical research modeling how financial knowledge can be cast as a type of investment in human capital. In this framework, those who build financial savvy can earn above-average expected returns on their investments, yet there will still be some optimal level of financial ignorance. Endogenizing financial knowledge has important implications for welfare, and this perspective also offers insights into programs intended to enhance levels of financial knowledge in the larger population.

Another of our goals is to assess the effects of financial literacy on important economic behaviors. We do so by drawing on evidence about what people know and which groups are the least financially literate. Moreover, the literature allows us to tease out the impact of financial literacy on economic decision-making in the United States and abroad, along with the costs of financial ignorance. Because this is a new area of economic research, we conclude with thoughts on policies to help fill these gaps; we focus on what remains to be learned to better inform theoretical/empirical models and public policy.

2. A Theoretical Framework for Financial Literacy

The conventional microeconomic approach to saving and consumption decisions posits that a fully rational and well-informed individual will consume less than his income in times of high earnings, thus saving to support consumption when income falls (e.g. after retirement). Starting with Modigliani and Brumberg (1954) and Friedman (1957) , the consumer is posited to arrange his optimal saving and decumulation patterns to smooth marginal utility over his lifetime. Many studies have shown how such a life cycle optimization process can be shaped by consumer preferences (e.g. risk aversion and discount rates), the economic environment (e.g. risky returns on investments and liquidity constraints), and social safety net benefits (e.g. the availability and generosity of welfare schemes and Social Security benefits), among other features. 4

These microeconomic models generally assume that individuals can formulate and execute saving and spend-down plans, which requires them to have the capacity to undertake complex economic calculations and to have expertise in dealing with financial markets. As we show below in detail, however, few people seem to have much financial knowledge. Moreover, acquiring such knowledge is likely to come at a cost. In the past, when retirement pensions were designed and implemented by governments, individual workers devote very little attention to their plan details. Today, by contrast, since saving, investment, and decumulation for retirement are occurring in an increasingly personalized pension environment, the gaps between modeling and reality are worth exploring, so as to better evaluate where the theory can be enriched, and how policy efforts can be better targeted.

Though there is a substantial theoretical and empirical body of work on the economics of education, 5 far less attention has been devoted to the question of how people acquire and deploy financial literacy. In the last few years, however, a few papers have begun to examine the decision to acquire financial literacy and to study the links between financial knowledge, saving, and investment behavior ( Delavande, Rohwedder, and Willis 2008 ; Jappelli and Padula 2013 ; Hsu 2011 ; and Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell 2013 ). 6 For instance, Delavande, Rohwedder, and Willis (2008) present a simple two-period model of saving and portfolio allocation across safe bonds and risky stocks, allowing for the acquisition of human capital in the form of financial knowledge ( à la Ben-Porath, 1967 , and Becker, 1975 ). That work posits that individuals will optimally elect to invest in financial knowledge to gain access to higher-return assets: this training helps them identify better-performing assets and/or hire financial advisers who can reduce investment expenses. Hsu (2011) uses a similar approach in an intra-household setting where husbands specialize in the acquisition of financial knowledge, while wives increase their acquisition of financial knowledge mostly when it becomes relevant (such as prior to the death of their spouses). Jappelli and Padula (2013) also consider a two-period model but additionally sketch a multi-period life cycle model with financial literacy endogenously determined. They predict that financial literacy and wealth will be strongly correlated over the life cycle, with both rising until retirement and falling thereafter. They also suggest that in countries with generous Social Security benefits, there will be fewer incentives to save and accumulate wealth and, in turn, less reason to invest in financial literacy.

Each of these studies represents a useful theoretical advance, yet none incorporates key features now standard in theoretical models of saving – namely borrowing constraints, mortality risk, demographic factors, stock market returns, and earnings and health shocks. These shortcomings are rectified in recent work by Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell (2011 , 2013 ), which calibrates and simulates a multi-period dynamic life cycle model where individuals not only select capital market investments but also undertake investments in financial knowledge. This extension is important in that it permits the researchers to examine model implications for wealth inequality and welfare. Two distinct investment technologies are considered: the first is a simple technology which pays a fixed low rate of return each period ( R ¯ = 1 + r ¯ ) , similar to a bank account, while the second is a more sophisticated technology providing the consumer access to a higher stochastic expected return, R ∼ ( f t ) , which depends on his accumulated level of financial knowledge. Each period, the stock of knowledge is related to what the individual had in the previous period minus a depreciation factor: thus f t +1 = δ f t + i t , where δ represents knowledge depreciation (due to obsolescence or decay), and gross investment in knowledge is indicated with i t . The stochastic return from the sophisticated technology follows the process R ∼ ( f t + 1 ) = R ¯ + r ( f t + 1 ) + σ ε ε t + 1 (where ε t is a N(0,1) iid shock and σ ε refers to the standard deviation of returns on the sophisticated technology). To access this higher expected return, the consumer must pay both a direct cost (c), and a time and money cost ( π ) to build up knowledge. 7

Prior to retirement, the individual earns risky labor income ( y ) from which he can consume or invest so as to raise his return (R) on saving (s) by investing in the sophisticated technology. After retirement, the individual receives Social Security benefits which are a percentage of pre-retirement income. 8 Additional sources of uncertainty include stock returns, medical costs, and longevity. Each period, therefore, the consumer’s decision variables are how much to invest in the capital market, consume ( c ), and whether to invest in financial knowledge.

Assuming a discount rate of β and η o , η y , and ε which refer, respectively, to shocks in medical expenditures, labor earnings, and rate of return, the problem takes the form of a series of Bellman equations with the following value function V d ( s t ) at each age as long as the individual is alive ( p e , t > 0):

The utility function is assumed to be strictly concave in consumption and scaled using the function u ( c t / n t ) where n t is an equivalence scale capturing family size which changes predictably over the life cycle; and by education, subscripted by e . End-of-period assets ( a t +1 ) are equal to labor earnings plus the returns on the previous period’s saving plus transfer income (tr) , minus consumption and costs of investment in knowledge (as long as investments are positive; i.e., κ > 0. Accordingly, a t + 1 = R ∼ κ ( f t + 1 ) ( a t + y e , t + t r t − c t − π ( i t ) − c d I ( κ t > 0 ) ) 9 .

After calibrating the model using plausible parameter values, the authors then solve the value functions for consumers with low/medium/high educational levels by backward recursion. 10 Given paths of optimal consumption, knowledge investment, and participation in the stock market, they then simulate 5,000 life cycles allowing for return, income, and medical expense shocks. 11

Several key predictions emerge from this study. First, endogenously-determined optimal paths for financial knowledge are hump-shaped over the life cycle. Second, consumers invest in financial knowledge to the point where their marginal time and money costs of doing so are equated to their marginal benefits; of course, this optimum will depend on the cost function for financial knowledge acquisition. Third, knowledge profiles differ across educational groups because of peoples’ different life cycle income profiles.

Importantly, this model also predicts that inequality in wealth and financial knowledge will arise endogenously without having to rely on assumed cross-sectional differences in preferences or other major changes to the theoretical setup. 12 Moreover, differences in wealth across education groups also arise endogenously; that is, some population subgroups optimally have low financial literacy, particularly those anticipating substantial safety net income in old age. Finally, the model implies that financial education programs should not be expected to produce large behavioral changes for the least educated, since it may not be worthwhile for the least educated to incur knowledge investment costs given that their consumption needs are better insured by transfer programs. 13 This prediction is consistent with Jappelli and Padula’s (2013) suggestion that less financially informed individuals will be found in countries with more generous Social Security benefits (see also Jappelli 2010 ).

Despite the fact that some people will rationally choose to invest little or nothing in financial knowledge, the model predicts that it can still be socially optimal to raise financial knowledge for everyone early in life, for instance by mandating financial education in high school. This is because even if the least educated never invest again and let their knowledge endowment depreciate, they will still earn higher returns on their saving which generates a substantial welfare boost. For instance, providing pre-labor market financial knowledge to the least educated group improves their wellbeing by an amount equivalent to 82 percent of their initial wealth ( Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell 2011 ). The wealth equivalent value for college graduates is also estimated to be substantial, at 56 percent. These estimates are, of course, specific to the calibration, but the approach underscores that consumers would benefit from acquiring financial knowledge early in life even if they made no new investments thereafter.

In sum, a small but growing theoretical literature on financial literacy has made strides in recent years by endogenizing the process of financial knowledge acquisition, generating predictions that can be tested empirically, and offering a coherent way to evaluate policy options. Moreover, these models offer insights into how policymakers might enhance welfare by enhancing young workers’ endowment of financial knowledge. In the next section, we turn to a review of empirical evidence on financial literacy and how to measure it in practice. Subsequently, we analyze existing studies on how financial knowledge matters for economic behavior in the empirical realm.

3. Measuring Financial Literacy

Several fundamental concepts lie at the root of saving and investment decisions as modeled in the life cycle setting described in the previous section. Three such concepts are: (i) numeracy and capacity to do calculations related to interest rates , such as compound interest; (ii) understanding of inflation ; and (iii) understanding of risk diversification . Translating these into easily-measured financial literacy metrics is difficult, but Lusardi and Mitchell (2008 , 2011b , c ) have designed a standard set of questions around these ideas and implemented them in numerous surveys in the United States and abroad.

Four principles informed the design of these questions. The first is Simplicity : the questions should measure knowledge of the building blocks fundamental to decision-making in an intertemporal setting. The second is Relevance : the questions should relate to concepts pertinent to peoples’ day-to-day financial decisions over the life cycle; moreover, they must capture general rather than context-specific ideas. Third is Brevity : the number of questions must be kept short to secure widespread adoption; and fourth is Capacity to differentiate , meaning that questions should differentiate financial knowledge to permit comparisons across people. These criteria are met by the three financial literacy questions designed by Lusardi and Mitchell (2008 Lusardi and Mitchell (2011b ), worded as follows:

Suppose you had $100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2% per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow: [more than $102, exactly $102, less than $102? Do not know, refuse to answer.]

Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year and inflation was 2% per year. After 1 year, would you be able to buy: [more than, exactly the same as, or less than today with the money in this account? Do not know; refuse to answer.]

Do you think that the following statement is true or false? ‘Buying a single company stock usually provides a safer return than a stock mutual fund.’ [Do not know; refuse to answer.]

The first question measures numeracy or the capacity to do a simple calculation related to compounding of interest rates. The second question measures understanding of inflation, again in the context of a simple financial decision. The third question is a joint test of knowledge about ‘stocks’ and ‘stock mutual funds’ and of risk diversification, since the answer to this question depends on knowing what a stock is and that a mutual fund is composed of many stocks. As is clear from the theoretical models described earlier, many decisions about retirement savings must deal with financial markets. Accordingly, it is important to understand knowledge of the stock market as well as differentiate between levels of financial knowledge.

Naturally any given set of financial literacy measures can only proxy for what individuals need to know to optimize behavior in intertemporal models of financial decision-making. 14 Moreover, measurement error is a concern, as well as the possibility that answers might not measure ‘true’ financial knowledge. These issues have implications for empirical work on financial literacy, to be discussed below.

Empirical Evidence of Financial Literacy in the Adult Population

The three questions above were first administered to a representative sample of U.S. respondents age 50 and older, in a special module of the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS). 15 Results, summarized in Table 1 , indicate that this older U.S. population is quite financially illiterate: only about half could answer the simple 2 percent calculation and knew about inflation, and only one third could answer all three questions correctly ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2011b ). This poor showing is notwithstanding the fact that people in this age group had made many financial decisions and engaged in numerous financial transactions over their lifetimes. Moreover, these respondents had experienced two or three periods of high inflation (depending on their age) and witnessed numerous economic and stock market shocks (including the demise of Enron), which should have provided them with information about investment risk. In fact, the question about risk is the one where respondents answered disproportionately with “Do not know.”

Financial Literacy Patterns in the United States

Source: Authors’ computations from HRS 2004 Planning Module

Note: DK = respondent indicated “don’t know.”

These same questions were added to several other U.S. surveys thereafter, including the 2007–2008 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) for young respondents (ages 23–28) ( Lusardi, Mitchell, and Curto 2010 ); the RAND American Life Panel (ALP) covering all ages ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2009 ); and the 2009 and 2012 National Financial Capability Study ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2011d ). 16 In each case, the findings underscore and extend the HRS results, in that for all groups, the level of financial literacy in the U.S. was found to be quite low.

Additional and more sophisticated concepts were then added to the financial literacy measures. For instance, the 2009 and 2012 National Financial Capability Survey included two items measuring sophisticated concepts such as asset pricing and understanding of mortgages/mortgage payments. Results revealed additional gaps in knowledge: for example, data from the 2009 wave show that only a small percentage of Americans (21%) knew about the inverse relationship between bond prices and interest rates ( Lusardi 2011 ). 17 A pass/fail set of 28 questions by Hilgert, Hogarth, and Beverly (2003) covered knowledge of credit, saving patterns, mortgages, and general financial management, and the authors concluded most people earned a failing score on these questions as well. 18 Lusardi, Mitchell and Curto (2012) also examine a set to questions measuring financial sophistication in addition to basic financial literacy and found that a large majority of older respondents are not financially sophisticated. Additional surveys have also examined financial knowledge in the context of debt. For example, Lusardi and Tufano (2009a , b ) examined ‘debt literacy’ regarding interest compounding and found that only one-third of respondents knew how long it would take for debt to double if one were to borrow at a 20 percent interest rate. This lack of knowledge confirms conclusions from Moore’s (2003) survey of Washington state residents, where she found that people frequently failed to understand interest compounding along with the terms and conditions of consumer loans and mortgages. Studies have also looked at different measures of “risk literacy” ( Lusardi, Schneider, and Tufano 2011 ). Knowledge of risk and risk diversification remains low even when the questions are formulated in alternative ways (see, Kimball and Shumway 2006 ; Yoong 2011 ; and Lusardi, Schneider, and Tufano 2011 ). In other words, all of these surveys confirm that most U.S. respondents are not financially literate.

Empirical Evidence of Financial Literacy among the Young

As noted above, it would be useful to know how well-informed people are at the start of their working lives. Several authors have measured high school students’ financial literacy using data from the Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy and the Council for Financial Education (CEE). Because those studies included a long list of questions, they provide a rather nuanced evaluation of what young people know when they enter the workforce. As we saw for their adult counterparts, most high school students in the U.S. receive a failing financial literacy grade ( Mandell 2008 ; Markow and Bagnaschi 2005 ). Similar findings are reported for college students ( Chen and Volpe 1998 ; and Shim, Barber, Card, Xiao, and Serido 2010 ).

International Evidence on Financial Literacy

The three questions mentioned earlier and that have been used in several surveys in the United States have also been used in several national surveys in other countries. Table 2 reports the findings from the twelve countries that have used these questions and where comparisons can be made for the total population. 19 For brevity, we only report the proportion of correct and do not know answers to each questions and for all questions.

Comparative Statistics on Responses to Financial Literacy Questions around the World

indicates questions that have slightly different wording than the baseline financial literacy questions enumerated in the text.

The table highlights a few key findings. First, few people across countries can correctly answer three basic financial literacy questions. In the U.S., only 30 percent can do so, with similar low percentages in countries having well-developed financial markets (Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, Australia and others), as well as in nations where financial markets are changing rapidly (Russia and Romania). In other words, low levels of financial literacy found in the U.S. are also prevalent elsewhere, rather than being specific to any given country or stage of economic development. Second, some of what adult respondents know is related to national historical experience. For example, Germans and Dutch are more likely to know the answer to the inflation question, whereas many fewer people do in Japan, a country that has experienced deflation. Countries that were planned economies in the past (such as Romania and Russia) displayed the lowest knowledge of inflation. Third, of the questions examined, risk diversification appears to be the concept that people have the most difficulty grasping. Virtually everywhere, a high share of people respond that they ‘do not know’ the answer to the risk diversification question. For instance, in the U.S., 34 percent of respondents state they do not know the answer to the risk diversification question; in Germany 32 percent and the Netherlands 33 percent do so; and even in the most risk-savvy country of Sweden and Switzerland, 18 and 13 percent respectively report they do not know the answer to the risk diversification question.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been a pioneer in highlighting the lack of financial literacy across countries. For example, an OECD report in 2005 documented extensive financial illiteracy in Europe, Australia, and Japan, among others. 20 More recently, Atkinson and Messy (2011 Atkinson and Messy (2012) confirmed the patterns of financial illiteracy mentioned earlier in the text across 14 countries at different stages of development in four continents, using a harmonized set of financial literacy as in the three questions that were used in many countries. 21

The goal of evaluating student financial knowledge around the world among the young (high school students) has recently been taken up by the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), 22 which in 2012 added a module on financial literacy to its review of proficiency in mathematics, science, and reading. Accordingly, 15-year olds around the world will be able to be compared with regard to their financial knowledge. In so doing, PISA has taken the position that financial literacy should be recognized as a skill essential for participation in today’s economy.

Objective versus Subjective Measures of Financial Literacy

Another interesting finding on financial literacy is that there is often a substantial mismatch between peoples’ self-assessed knowledge versus their actual knowledge , where the latter is measured by correct answers to the financial literacy questions posed. As one example, several surveys include questions asking people to indicate their self-assessed knowledge, as the following questions used in the United States and also in the Netherlands and Germany:

On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means very low and 7 means very high, how would you assess your overall financial knowledge?’

Even though actual financial literacy levels are low, respondents are generally rather confident of their financial knowledge and, overall, they tend to overestimate how much they know ( Table 3 ). For instance in the 2009 U.S. Financial Capability Study, 70 percent of respondents gave themselves score of 4 or higher (out of 7), but only 30 percent of the sample could answer the factual questions correctly ( Lusardi 2011 ). Similar findings were reported in other U.S. surveys and in Germany and the Netherlands ( Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and van Rooij 2012 ). One exception is Japan, where respondents gave themselves low grades in financial knowledge. In other words, though actual financial literacy is low, most people are unaware of their own shortcomings.

Comparative Statistics on Responses to Self-reported Financial Literacy

Note: This table reports respondents’ answers to the question: “On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means very low and 7 means very high, how would you assess your overall financial knowledge?” Note that the question posed in Lusardi and Mitchell (2009) is different and asks the following: “How would you assess your understanding of economics (on a 7-point scale;1 means very low and 7 means very high)?” In Japan, respondents were asked whether they think that they know a lot about finance on a 1–5 point scale ( Sekita 2011 ).

Financial Literacy and Framing

Peoples’ responses to survey questions cannot always be taken at face value, a point well-known to psychometricians and economic statisticians. One reason, as noted above, is that financial literacy may be measured with error, depending on the way questions are worded. To test this possibility, Lusardi and Mitchell (2009) and van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie (2011) randomly asked two groups of respondents the same risk question, but randomized their order of presentation. Thus half the group received format (a) and the other half format (b), as follows:

Buying a company stock usually provides a safer return than a stock mutual fund. True or false?

Buying a stock mutual fund usually provides a safer return than a company stock. True or false?

They found that people’s responses were, indeed, sensitive to how the question was worded in both the U.S. American Life Panel ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2009 ) and the Dutch Central Bank Household Survey (DHS; van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie 2011 ). For example, fewer DHS respondents responded correctly when the wording was ‘buying a stock mutual fund usually provides a safer return than a company stock’; conversely, the fraction of correct responses doubled when shown the alternative wording: ‘buying a company stock usually provides a safer return than a stock mutual fund.’ This was not simply due to people using a crude rule of thumb (such as always picking the first as the correct answer), since that would generate a lower rather than a higher percentage of correct answers for version (a). Instead, it appeared that some respondents did not understand the question, perhaps because they were unfamiliar with stocks, bonds, and mutual funds. What this means is that some answers judged to be ‘correct’ may instead be attributable to guessing. In other words, analysis of the financial literacy questions should take into account the possibility that these measures may be noisy proxies of true financial knowledge levels. 23

4. Disaggregating Financial Literacy

To draw out lessons about which people most lack financial knowledge, we turn next to a disaggregated assessment of the data. In what follows, we briefly review evidence by age and sex, race/ethnicity, income and employment status, and other factors of interest to researchers.

Financial Literacy Patterns by Age

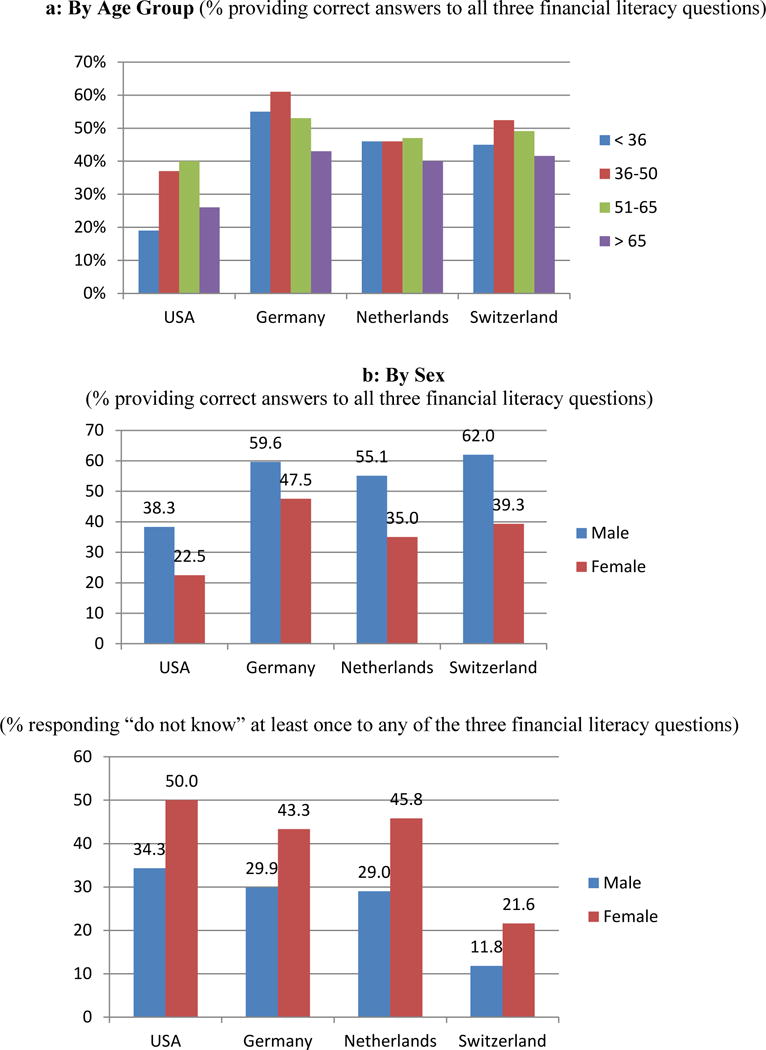

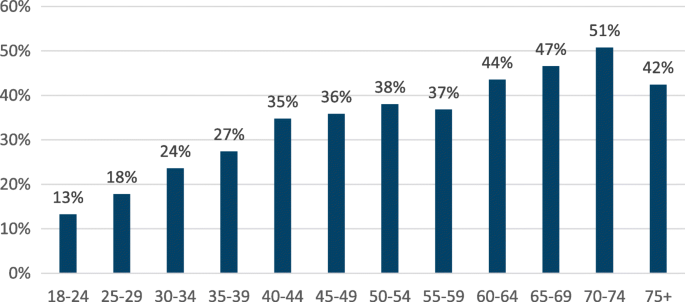

The theoretical framework sketched above implies that the life cycle profile of financial literacy will be hump-shaped, and survey data confirm that financial literacy is, in fact, lowest among the young and the old. 24 This is a finding which is robust across countries and we report a selected set of countries in Figure 1 .

Financial Literacy Across Demographic Groups (Age, Sex, and Education)

Note: Data for Figure 1c are taken from Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011d (USA); Alessie, van Rooij, and Lusardi, 2011 (Netherlands), Bucher-Koenen and Lusardi, 2011 (Germany), and Brown and Graf, 2013 (Switzerland).

Of course with cross-sectional data, one cannot cleanly disentangle age from cohort effects, so further analysis is required to identify these clearly, and below we comment further on this point ( Figure 1a ). Nevertheless, it is of interest that older people give themselves very high scores regarding their own financial literacy, despite scoring poorly on the basic financial literacy questions ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2011b ; Lusardi and Tufano 2009a ) and not just in the US but other countries as well ( Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ). Similarly, Finke, Howe, and Houston (2011) develop a multidimensional measure of financial literacy for the old and confirm that, though actual financial literacy falls with age, peoples’ confidence in their own financial decision-making abilities actually increases with age. The mismatch between actual and perceived knowledge might explain why financial scams are often perpetrated against the elderly ( Deevy, Lucich, and Beals 2012 ).

Financial Literacy Differences by Sex

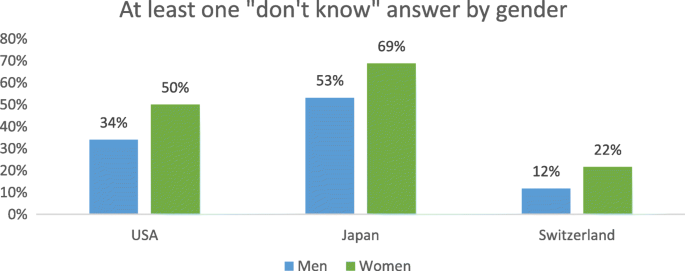

One striking feature of the empirical data on financial literacy is the large and persistent gender difference described in Figure 1b . Not only are older men generally more financially knowledgeable than older women, but similar patterns also show up among younger respondents as well ( Lusardi, Mitchell, and Curto 2010 ; Lusardi and Mitchell 2009 ; Lusardi and Tufano 2009a , b ). Moreover, these gaps persist across both the basic and the more sophisticated literacy questions ( Lusardi, Mitchell, and Curto 2012 ; Hung, Parker, and Yoong 2009 ).

One twist on the differences by sex, however, is that while women are less likely to answer financial literacy questions correctly than men, they are also far more likely to say they ‘do not know’ an answer to a question, a result that is strikingly consistent across countries ( Figure 1b ). 25 This awareness of their own lack of knowledge may make women ideal targets for financial education programs.

Because these sex differences in financial literacy are so persistent and widespread across surveys and countries, several researchers have sought to explain them. Consistent with the theoretical framework described earlier, Hsu (2011) proposed that some sex differences may be rational, with specialization of labor within the household leading married women to build up financial knowledge only late in life (close to widowhood). Nonetheless, that study did not explain why financial literacy is also lower among single women in charge of their own finances. Studies of financial literacy in high school and college also revealed sex differences in financial literacy early in life ( Chen and Volpe 2002 ; Mandell 2008 ). 26 Other researchers seeking to explain observed sex differences concluded that traditional explanations cannot fully account for the observed male/female knowledge gap ( Fonseca, Mullen, Zamarro, and Zissimopolous 2012 ; Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie, and van Rooij 2012 ). Fonseca, Mullen, Zamarro, and Zissimopoulos (2012) suggested that women may acquire or ‘produce’ financial literacy differently from men, while Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie, and van Rooij (2012) pointed to a potentially important role for self-confidence that differs by sex. Brown and Graf (2013) also showed that sex differences are not due to differential interest in finance and financial matters between women and men.

To shed more light on women’s financial literacy, Mahdavi and Horton (2012) examined alumnae from a highly selective U.S. women’s liberal arts college. Even in this talented and well-educated group, women’s financial literacy was found to be very low. In other words, even very well educated women are not particularly financially literate, which could imply that women may acquire financial literacy differently from men. Nevertheless this debate is far from closed, and additional research will be required to better understand these observed sex differences in financial literacy.

Literacy Differences by Education and Ability

As illustrated in Figure 1c , there are substantial differences in financial knowledge by education: specifically, those without a college education are much less likely to be knowledgeable about basic financial literacy concepts, as reported in several U.S. surveys and across countries ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2007a , 2011c ). Moreover, numeracy is especially poor for those with low educational attainment ( Christelis, Jappelli, and Padula 2010 , Lusardi, 2012 ).

How to interpret the finding of a positive link between education and financial savvy has been subject to some debate in the economics literature. One possibility is that the positive correlation might be driven by cognitive ability ( McArdle, Smith, and Willis 2009 ), implying that one must control on measures of ability when seeking to parse out the separate impact of financial literacy. Fortunately, the NLSY has included both measures of financial literacy and of cognitive ability (i.e., the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery). Lusardi, Mitchell, and Curto (2010) did find a positive correlation between financial literacy and cognitive ability among young NLSY respondents, but they also showed that cognitive factors did not fully account for the variance in financial literacy. In other words, substantial heterogeneity in financial literacy remains even after controlling on cognitive factors.

Other Literacy Patterns

There are numerous other empirical regularities in the financial literacy literature, that are again persistent across countries. Financial savvy varies by income and employment type, with lower-paid individuals doing less well and employees and the self-employed doing better than the non-employed ( Lusardi and Tufano 2009a ); Lusardi and Mitchell 2011c ). Several studies have also reported marked differences by race and ethnicity, with African Americans and Hispanics displaying the lowest level of financial knowledge in the U.S. context ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2007a , b , 2011d ). These findings hold across age groups and many different financial literacy measures ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2009 ). Those living in rural areas generally score worse than their city counterparts ( Klapper and Panos 2011 ). These findings might suggest that financial literacy is more easily acquired via interactions with others, in the workplace or in the community. 27 Relatedly, there are also important geographic differences in financial literacy; for example, Fornero and Monticone (2011) report substantial financial literacy dispersion across regions in Italy and so does Beckmann (2013) for Romania Bumcrot, Lin, and Lusardi (2013) report similar differences across U.S. states.

The literature also points to differences in financial literacy by family background. For instance, Lusardi, Mitchell, and Curto (2010) linked financial literacy of 23–28-year-old NLSY respondents to characteristics of the households in which they grew up, controlling for a set of demographic and economic characteristics. Respondents’ financial literacy was also significantly positively correlated with parental education (in particular, that of their mothers), and whether their parents held stocks or retirement accounts when the respondents were teenagers. Mahdavi and Horton (2012) reported a connection between financial literacy and parental background; in this case, fathers’ education was positively associated with their female children’s financial literacy. 28 In other words, financial literacy may well get its start in the family, perhaps when children observe their parents’ saving and investing habits, or more directly by receiving financial education from parents ( Chiteji and Stafford 1999 ; Li 2009 ; Shim, Xiao, Barber, and Lyons 2009 ).

Other studies have noted a nationality gap in financial literacy, with foreign citizens reporting lower financial literacy than the native born ( Brown and Graf 2013 ). Others have found differences in financial literacy according to religion ( Alessie, Van Rooij and Lusardi, 2011 ) and political opinions ( Arrondel, Debbich and Savignac 2013 ). These findings may also shed light on how financial literacy is acquired.

To summarize, while financial illiteracy is widespread, it is also concentrated among specific population sub-groups in most countries studied to date. Such heterogeneity in financial literacy suggests that different mechanisms may be appropriate for tracking the causes and possible consequences of the shortfalls. In the U.S., those facing most challenges are the young and the old, women, African-Americans, Hispanics, the least educated, and those living in rural areas. To date, these differences have not been fully accounted for, though the theoretical framework outlined above provides guidelines for explaining some of these.

5. How Does Financial Literacy Matter?

We turn next to a discussion of whether and how financial literacy matters for economic decision-making. 29 Inasmuch as individuals are increasingly being asked to take on additional responsibility for their own financial well-being, there remains much to learn about these facts. And as we have argued above, when financial literacy itself is a choice variable, it is important to disentangle cause from effect. For instance, those with high net worth who invest in financial markets may also be more likely to care about improving their financial knowledge, since they have more at stake. In what follows, we discuss research linking financial literacy with economic outcomes, taking into account the endogeneity issues as well.

Financial Literacy and Economic Decisions

The early economics literature in this area began by documenting the link between financial literacy and several economic behaviors. For example Bernheim (1995 , 1998 ) was among the first to emphasize that most U.S. households lacked basic financial knowledge and that they also used crude rules of thumb when engaging in saving behavior. More recently, Calvet, Campbell, and Sodini (2007 Calvet, Campbell, and Sodini (2009) evaluated Swedish investors’ actions that they classified as ‘mistakes.’ While that analysis included no direct financial literacy measure, the authors did report that poorer, less educated, and immigrant households (attributes associated with low financial literacy, as noted earlier) were more likely to make financial errors. Agarwal, Driscoll, Gabaix, and Laibson (2009) also focused on financial ‘mistakes’, showing that these were most prevalent among the young and the old, groups which normally display the lowest financial knowledge.

In the wake of the financial crisis of 2008–9, the U.S. federal government has also begun to express substantial concern about another and more extreme case of mistakes, namely where people fall prey to financial scams. As often noted, scams tend to be perpetrated against the elderly, since they are among those with the least financial savvy and often have accumulated some assets. 30 A survey of older financial decision makers (age 60+) indicated that more than half of them reported having made a bad investment, and one in five of those respondents felt they had been misled or defrauded but failed to report the situation ( FINRA 2006 ). As Baby Boomers age, this problem is expected to grow ( Blanton 2012 ), since this cohort is a potentially lucrative target.

Several researchers have examined the relationships between financial literacy and economic behavior. It is much harder to establish a causal link between the two and we will discuss the issue of endogeneity and other problems in more detail below. Hilgert, Hogarth, and Beverly (2003) uncovered a strong correlation between financial literacy and day-to-day financial management skills. Several other studies both in the United States and other countries have found that the more numerate and financially literate are also more likely to participate in financial markets and invest in stocks ( Kimball and Shumway 2006 ; Christelis, Jappelli, and Padula 2010 ; van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie 2011 ; Yoong 2011 ; Almenberg and Dreber 2011 ; Arrondel, Debbich, and Savignac 2012 ). Financial literacy can also be linked to holding precautionary savings ( de Bassa Scheresberg 2013 ).

The more financially savvy are also more likely to undertake retirement planning, and those who plan also accumulate more wealth ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2007a , b , 2011a , 2011b ). Some of the first studies on the effects of financial literacy were linked to its effects on retirement planning in the United States and these studies have been replicated in most of the countries covered in Table 2 , showing that the correlation between financial literacy and different measures of retirement planning is quite robust. 31 Studies breaking out specific components of financial literacy tend to conclude that what matters most is advanced financial knowledge (for example, risk diversification) and the capacity to do calculations ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2011d ; Alessie, van Rooij, and Lusardi 2011 ; Fornero and Monticone 2011 ; Klapper and Panos 2011 ; Sekita 2011 ).

Turning to the liability side of the household balance sheet, Moore (2003) reported that the least financially literate are also more likely to have costly mortgages. Campbell (2006) pointed out that those with lower income and less education (characteristics strongly related to financial illiteracy) were less likely to refinance their mortgages during a period of falling interest rates. Stango and Zinman (2009) concluded that those unable to correctly calculate interest rates out of a stream of payments ended up borrowing more and accumulating less wealth. Lusardi and Tufano (2009a ) confirmed that the least financially savvy incurred high transaction costs, paying higher fees and using high-cost borrowing. In their study, the less knowledgeable also reported that their debt loads were excessive, or that they were unable to judge their debt positions. Similarly, Mottola (2013) found that those with low financial literacy were more likely to engage in costly credit card behavior, and Utkus and Young (2011) concluded that the least literate were also more likely to borrow against their 401(k) and pension accounts.

Moreover, both self-assessed and actual literacy is found to have an effect on credit card behavior over the life cycle ( Allgood and Walstad, 2013 ). A particularly well-executed study by Gerardi, Goette, and Meier (2013) matched individual measures of numerical ability to administrative records that provide information on subprime mortgage holders’ payments. Three important findings flowed from this analysis. First, numerical ability was a strong predictor of mortgage defaults. Second, the result persisted even after controlling for cognitive ability and general knowledge. Third, the estimates were quantitatively important, as will be discussed in more detail below, an important finding for both regulators and policymakers.

Many high-cost methods of borrowing have proliferated over time, with negative effects for less savvy consumers. 32 For instance, Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg (2013) examined high-cost borrowing in the U.S. including payday loans, pawn shops, auto title loans, refund anticipation loans, and rent-to-own shops. They concluded that the less financially literate were substantially more likely to use high-cost methods of borrowing, a finding that is particularly strong among young adults (age 25–34) ( Bassa Scheresberg 2013 ). While most attention has been devoted to the supply side, these studies suggest it may also be important to look at the demand side and the financial literacy of borrowers. The large number of mortgage defaults during the financial crisis has likewise suggested to some that debt and debt management is a fertile area for mistakes; for instance, many borrowers do not know what interest rates were charged on their credit card or mortgage balances ( Moore 2003 ; Lusardi 2011 ; Disney and Gathergood 2012 ). 33

It is true that education can be quite influential in many of these arenas. For instance, research has shown that the college educated are more likely to own stocks and less prone to use high-cost borrowing ( Haliassos and Bertaut 1995 ; Campbell 2006 ; Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg 2012 ). Likewise, there is a very strong positive correlation between education and wealth-holding ( Bernheim and Scholz 1993 ). But for our purposes, including controls for educational attainment in empirical models of stock holding, wealth accumulation, and high-cost methods of borrowing, does not diminish the statistical significance of financial literacy and in fact it often enhances it ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2011b ; Behrman, Mitchell, Soo, and Bravo 2012 ; van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie 2011 , 2012 ; Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg 2013 ). Evidently, general knowledge (education) and more specialized knowledge (financial literacy) both contribute to more informed financial decision-making. In other words, investment in financial knowledge appears to be a specific form of human capital, rather than being simply associated with more years of schooling. Financial literacy is also linked to the demand for on-the-job training ( Clark, Ogawa, and Matsukura 2010 ) and being able to cope with financial emergencies ( Lusardi, Schneider, and Tufano 2011 ).

Costs of Financial Ignorance Pre-retirement

In the wake of the financial crisis, many have become interested in the costs of financial illiteracy as well as its distributional impacts. For instance, in the Netherlands, van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie (2011) estimate that being in the 75 th versus the 25 th percentile of the financial literacy index equals around €80,000 in terms of differential net worth (i.e., roughly 3.5 times the net disposable income of a median Dutch household). They also point out that an increase in financial literacy from the 25 th to the 75 th percentile for an otherwise average individual is associated with a 17–30 percentage point higher probability of stock market participation and retirement planning, respectively. In the U.S., simulations from a life-cycle model that incorporates financial literacy shows that financial literacy alone can explain more than half the observed wealth inequality ( Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell 2013 ). This result is obtained by comparing wealth to income ratios across education groups in models with and without financial literacy, which allows individuals to earn higher returns on their savings. For this reason, if the effects of financial literacy on financial behavior can be taken as causal, the costs of financial ignorance are substantial.

In the U.S., investors are estimated to have foregone substantial equity returns due to fees, expenses, and active investment trading costs, in an attempt to ‘beat the market.’ French (2008) calculates that this amounts to an annual total cost of around $100 billion, which could be avoided by passive indexing. Since the least financially literate are unlikely to be sensitive to fees, they are most likely to bear such costs. Additionally, many of the financially illiterate have been shown to shun the stock market, which Cocco, Gomes, and Maenhout (2005) suggested imposed welfare losses amounting to four percent of wealth. The economic cost of under-diversification computed by Calvet, Campbell, and Sodini (2007) is also substantial: they concluded that a median investor in Sweden experienced an annual return loss of 2.9 percent on a risky portfolio, or 0.5 percent of household disposable income. But for one in 10 investors, these annual costs were much higher, 4.5 percent of disposable income.

Costs of financial ignorance arise not only in the saving and investment arena, but also influence how consumers manage their liabilities. Campbell (2006) reported that suboptimal refinancing among U.S. homeowners resulted in 0.5–1 percent per year higher mortgage interest rates, or in aggregate, $50–100 billion annually. And as noted above, the least financially savvy are least likely to refinance their mortgages. Gerardi, Goette, and Meier (2013) showed that numerical ability may have contributed substantially to the massive defaults on subprime mortgages in the recent financial crisis. According to their estimates, those in the highest numerical ability grouping had about a 20 percentage point lower probability of defaulting on their subprime mortgages than those in the lowest financial numeracy group.

One can also link ‘debt literacy’ regarding credit card behaviors that generate fees and interest charges to paying bills late, going over the credit limit, using cash advances, and paying only the minimum amount due. Lusardi and Tufano (2009a ) calculated the “cost of ignorance” or transaction costs incurred by less-informed Americans and the component of these costs related to lack of financial knowledge. Their calculation of expected costs had two components—the likelihood and the costs of various credit card behaviors. These likelihoods were derived directly from empirical estimates using the data on credit card behavior, debt literacy, and a host of demographic controls that include income. They showed that, while less knowledgeable individuals constitute only 29 percent of the cardholder population, they accounted for 42 percent of these charges. Accordingly, the least financially savvy bear a disproportionate share of the costs associated with fee-inducing behaviors. Indeed, the average fees paid by those with low knowledge were 50 percent higher than those paid by the average cardholder. And of these four types of charges incurred by less-knowledgeable cardholders, one-third were incremental charges linked to low financial literacy.

Another way that the financially illiterate spend dearly for financial services is via high-cost forms of borrowing, including payday loans. 34 While the amount borrowed is often low ($300 on average), such loans are often made to individuals who have five or more such transactions per year ( Center for Responsible Lending 2004 ). It turns out that these borrowers also frequently fail to take advantage of other, cheaper opportunities to borrow. Agarwal, Skiba, and Tobacman (2009) studied payday borrowers who also have access to credit cards, and they found that two-thirds of their sample had at least $1,000 in credit card liquidity on the day they took out their first payday loan. This points to a pecuniary mistake: given average charges for payday loans and credit cards and considering a two-week payday loan of $300, the use of credit cards would have saved these borrowers substantial amounts – around $200 per year (and more if they took out repeated payday loans). While there may be good economic reasons why some people may want to keep below their credit card limits, including unexpected shocks, Bertrand and Morse (2011) determined that payday borrowers often labored under cognitive biases, similar to those with low financial literacy ( Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg 2013 ).

Costs of Financial Ignorance in Retirement

Financial knowledge impacts key outcomes including borrowing, saving, and investing decisions not only during the worklife, but afterwards, in retirement, as well. In view of the fact that people over the age of 65 hold more than $18 trillion in wealth, 35 this is an important issue.

Above we noted that financial literacy is associated with greater retirement planning and greater retirement wealth accumulation. 36 Hence it stands to reason that the more financially savvy will likely be better financially endowed when they do retire. A related point is that the more financially knowledgeable are also better informed about pension system rules, pay lower investment fees in their retirement accounts, and diversify their pension assets better ( Arenas de Mesa, Bravo, Behrman, Mitchell, and Todd 2008 ; Chan and Stevens 2008 ; Hastings, Mitchell, and Chyn 2011 ). 37 To date, however, relatively little has been learned about whether more financially knowledgeable older adults are also more successful at managing their resources in retirement, though the presence of scams among the elderly suggests that this topic is highly policy-relevant.

This is a particularly difficult set of decisions requiring retirees to look ahead to an uncertain future when making irrevocable choices with far-reaching consequences. For instance, people must forecast their (and their partner’s) survival probabilities, investment returns, pension income, and medical and other expenditures. Moreover, many of these financial decisions are once-in-a-lifetime events, including when to retire and claim one’s pension and Social Security benefits. Accordingly, it would not be surprising if financial literacy enhanced peoples’ ability to make these important and consequential decisions.

This question is especially relevant when it comes to the decision of whether retirees purchase lifetime income streams with their assets, since by so doing, they insure themselves from running out of income in old age. 38 Nevertheless, despite the fact that this form of longevity protection is very valuable in theory, relatively few payout annuities are purchased in practice in virtually every country ( Mitchell, Piggott, and Takayama 2011 ). New research points to the importance of framing and default effects in this decision process ( Agnew and Szkyman 2011 ; Brown, Kapteyn, and Mitchell 2013 ). This conclusion was corroborated by Brown, Kapteyn, Luttmer, and Mitchell (2011) , who demonstrated experimentally that people valued annuities less when they were offered the opportunity to buy additional income streams, and they valued annuities more if offered a chance to exchange their annuity flows for a lump sum. 39 Importantly for the present purpose, the financially savvy provided more consistent responses across alternative ways of eliciting preferences. By contrast, the least financially literate gave inconsistent results and respond to irrelevant cues when presented with the same set of choices. In other words, financial literacy appears to be highly influential in helping older households equip themselves with longevity risk protection in retirement.

Much more must be learned about how peoples’ financial decision-making abilities change with age, and how these are related to financial literacy. For instance, Agarwal, Driscoll, Gabaix, and Laibson (2009) reported that the elderly pay much more than the middle-aged for 10 financial products; 40 the 75-year-olds in their sample paid about $265 more per year for home equity lines of credit than did the 50-year-olds. How the patterns might vary by financial literacy is not yet known, but it might be that those with greater baseline financial knowledge are better able to deal with financial decisions as they move into the second half of their lifetimes. 41

Coping with Endogeneity and Measurement Error

Despite an important assembly of facts on financial literacy, relatively few empirical analysts have accounted for the potential endogeneity of financial literacy and the problem of measurement error in financial literacy alluded to above. In the last five years or so, however, several authors have implemented instrumental variables (IV) estimation to assess the impact of financial literacy on financial behavior, and the results tend to be quite convincing. To illustrate the ingenuity of the instruments used, Table 4 lists several studies along with the instruments used in their empirical analysis. Some of the descriptive evidence on financial literacy discussed earlier may explain why these instruments may be anticipated to predict financial literacy.

Instrumental Variable (IV) Estimation of the Effect of Financial Literacy on Behavior

It is useful to offer a handful of comments on some of the papers with particularly strong instruments. Christiansen, Joensen, and Rangvid (2008) used the opening of a new university in a local area—arguably one of the most exogenous variables one can find— as instrument for knowledge, and they concluded that economics education is an important determinant of investment in stocks. Following this lead, Klapper, Lusardi and Panos (2012) used the number of public and private universities in the Russian regions and the total number of newspapers in circulation as instruments for financial literacy. They found that financial literacy affected a variety of economic indicators including having bank accounts, using bank credit, using informal credit, having spending capacity, and the availability of unspent income. Lusardi and Mitchell (2009) instrumented financial literacy using the fact that different U.S. states mandated financial education in high school in different states and at different points in time and they interacted these mandates with state expenditures on education. Behrman, Mitchell, Soo, and Bravo (2012) employed several instruments including exposure to a new educational voucher system in Chile to isolate the causal effects of financial literacy and schooling attainment on wealth. Their IV results showed that both financial literacy and schooling attainment were positively and significantly associated with wealth levels.

Van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie (2011) instrumented financial literacy with the financial experiences of siblings and parents, since these were arguably not under respondents’ control, to rigorously evaluate the relationship between financial literacy and stock market participation. The authors reported that instrumenting greatly enhanced the measured positive impact of financial literacy on stock market participation. These instruments were also recently used by Agnew, Bateman and Thorp (2013) to assess the effect of financial literacy on retirement planning in Australia. Bucher-Koenen and Lusardi (2011) used political attitudes at the regional level in Germany as an instrument, arguing that free-market oriented supporters are more likely to be financially literate, and the assumption is that individuals can learn from others around them. The study by Arrondel, Debbich, and Savignac (2013) also shows some differences in financial literacy across political affiliation.

Interestingly, in all these cases, the IV financial literacy estimates always proves to be larger than the ordinary least squares estimates ( Table 4 ). This might be that people affected by the instruments have large responses or there is severe measurement error, but on the other hand, it seems clear that the non-instrumented estimates of financial literacy may underestimate the true effect.

Despite these advances, one might worry that other omitted variables could still influence financial decisions in ways that could bias results. For example, unobservables such as discount rates ( Meier and Sprenger 2008 ), IQ ( Grinblatt, Keloharju, and Linnainmaa 2011 ), or cognitive abilities could influence saving decisions and portfolio choice ( Delavande, Rohwedder, and Willis 2008 ; Korniotis and Kumar 2011 ). If these cannot be controlled for, estimated financial literacy impacts could be biased. However, Alessie, van Rooij, and Lusardi’s (2011) work using panel data and fixed-effects regression as well as IV estimation confirmed the positive effect of financial literacy on retirement planning, and several studies, as mentioned earlier (c.f., Gerardi, Goette and Meier 2013 ), account explicitly for cognitive ability. Nevertheless, they show that numeracy has an effect above and beyond cognitive ability.

A different way to parse out the effects of financial literacy on economic outcomes is to use a field experiment in which one group of individuals (the treatment group) is exposed to a financial education program and their behavior is then compared to that of a second group not thus exposed (the control group). Yet even in countries with less developed financial markets and pension systems, financial literacy impacts are similar to those found when examining the effect of financial literacy on retirement planning and pension participation ( Lusardi and Mitchell 2011c ). For example, Song (2011) showed that learning about interest compounding produces a sizeable increase in pension contributions in China. Randomized experimental studies in Mexico and Chile demonstrated that more financially literate individuals were more likely to choose pension accounts with lower administrative fees ( Hastings and Tejeda-Ashton 2008 ; Hastings and Mitchell 2011 ; Hastings, Mitchell, and Chyn 2011 ). More financially sophisticated individuals in Brazil were also less affected by their peers’ choices in their financial decisions ( Bursztyn, Ederer, Ferman, and Yuchtman 2013 ).

The financial crisis has also provided a laboratory to study the effects of financial literacy against a backdrop of economic shocks. For example, when stock markets dropped sharply around the world, investors were exposed to large losses in their portfolios. This combined with much higher unemployment has made it even more important to be savvy in managing limited resources. Bucher-Koenen and Ziegelmeyer (2011) examined the financial losses experienced by German households during the financial crisis and confirmed that the least financially literate were more likely to sell assets that had lost value, thus locking in losses. 42 In Russia, Klapper, Lusardi, and Panos (2012) found that the most financially literate were significantly less likely to report having experienced diminished spending capacity and had more available saving. Additionally, estimates from different time periods implied that financial literacy better equips individuals to deal with macroeconomic shocks.

Given this evidence on the negative outcomes and costs of financial illiteracy, we turn next to financial education programs to remedy these shortfalls.

6. Assessing the Effects of Financial Literacy Programs

Another way to assess the effects of financial literacy is to look at the evidence on financial education programs whose aims and objectives are to improve financial knowledge. Financial education programs in the U.S. and elsewhere have been implemented over the years in several different settings: in schools, workplaces, and libraries, and sometimes population subgroups have been targeted. As one example, several U.S. states mandated financial education in high school at different points in time, generating ‘natural experiments’ utilized by Bernheim, Garrett, and Maki (2001) , one of the earliest studies in this literature. Similarly, financial education in high schools has recently been examined in Brazil and Italy ( Bruhn, Legovini, and Zia 2012 ; Romagnoli and Trifilidis 2012 ). In some instances, large U.S. firms have launched financial education programs (c.f. Bernheim and Garrett (2003) , Clark and D’Ambrosio (2008) , and Clark, Morrill, and Allen (2012a , b )). Often the employer’s intention is to boost defined benefit pension plan saving and participation ( Duflo and Saez 2003 , 2004 ; Lusardi, Keller, and Keller 2008 ; Goda, Manchester, and Sojourner 2012 ). Programs have also been adopted for especially vulnerable groups such as those in financial distress ( Collins and O’Rourke 2010 ).

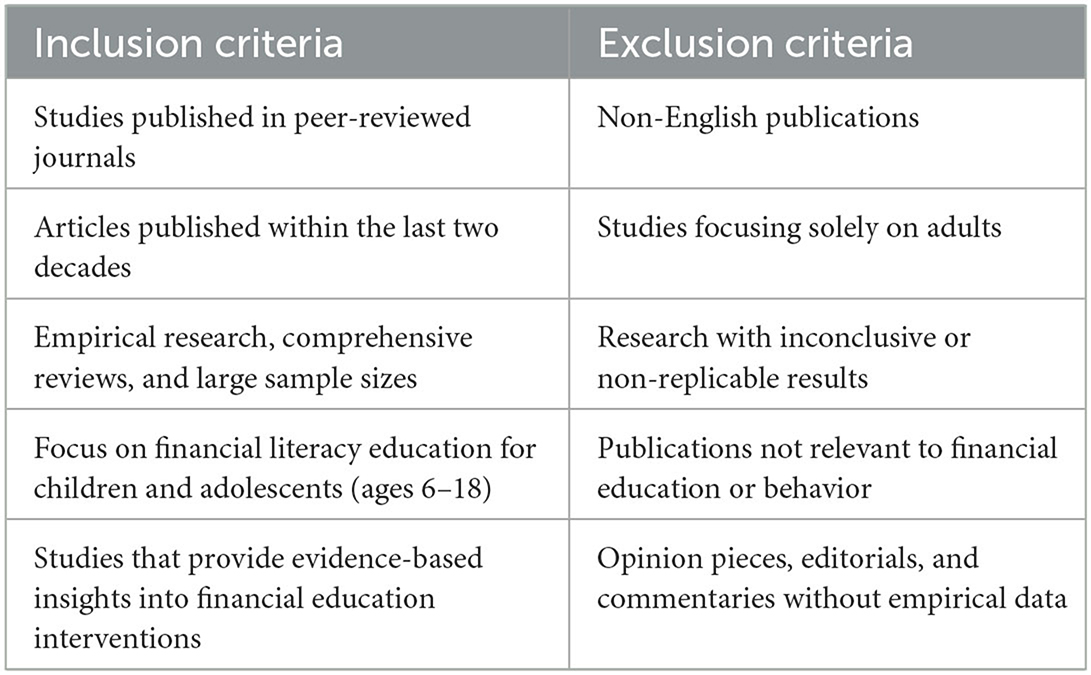

Despite the popularity of the programs, only a few authors have undertaken careful evaluations of the impact of financial education programs. Rather than detailing or reviewing the existing literature, 43 here we instead draw attention to the key issues which future researchers must take into account when evaluating the effectiveness of financial education programs. 44 We also highlight key recent research not reviewed in prior surveys.

A concern emphasized above in Section 2 is that evaluation studies have sometimes been conducted without a clear understanding of how financial knowledge is developed. That is, if we define financial literacy as a form of human capital investment, it stands to reason that some will find it optimal to invest in financial literacy while others will not. Accordingly, if a program were to be judged based on specific behavioral changes such as increasing retirement saving or participation in retirement accounts, it should be recognized that the program is unlikely, both theoretically and practically, to change everyone’s behavior in the same way. 45 For example, a desired outcome from a financial education program might be to boost saving. Yet for some, it may not be optimal to save; for others, it might be rational to reduce debt. Hence, unless an evaluator focused on the household portfolio problem including broader saving measures, a program might (incorrectly) be judged a failure.

A related concern is that, since such a large portion of the population is not financially knowledgeable about even the basic concepts of interest compounding, inflation, and risk diversification, it is unlikely that short exposure to financial literacy training would make much of a dent in consumers’ decision-making prowess. For this reason, offering a few retirement seminars or sending employees to a benefit fair can be fairly ineffective ( Duflo and Saez 2003 , 2004 ). Additionally, few studies have undertaken a careful cost-benefit analysis, which should be a high priority for future research.

The evidence reported previously also shows there is substantial heterogeneity in both financial literacy and financial behavior, so that programs targeting specific groups are likely to be more effective than one-size-fits-all financial education programs. For example, Lusardi, Michaud and Mitchell (2013) show theoretically that there is substantial heterogeneity in individual behavior, implying that not everyone will gain from financial education. Accordingly, saving will optimally be zero (or negative) for some, and financial education programs in this case would not be expected to change that behavior. In other words, one should not expect a 100 percent participation rate in financial education programs. In this respect, the model delivers an important prediction: in order to change behavior, financial education programs must be targeted to specific groups of the population since people have different preferences and economic circumstances.

As in other fields of economic research, program evaluations must also be rigorous if they are to persuasively establish causality and effectiveness. As noted by Collins and O’Rourke (2010) , the ‘golden rule’ of evaluation is the experimental approach in which a ‘treatment’ group exposed to financial literacy education is compared with a ‘control’ group that is not (or that is exposed to a different treatment). Thus far, as noted above, few financial educational programs have been designed or evaluated with these standards in mind, making it difficult to draw inferences. A related point is that confounding factors may bias estimated impacts unless the evaluation is carefully structured. As an example, we point to the debate over the efficacy of teaching financial literacy in high school, a discussion that will surely be fed by the new financial literacy module in the 2012 PISA mentioned above. Some have argued against financial education in school (e.g., Willis 2008 ), drawing on the findings from the Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy ( Mandell 2004 , 2008 ). The Jump$tart studies concluded that students scored no better in financial literacy tests even if they attended school in states having financial education; in fact, in some cases, Mandell (1997 , 2008 ) found that they scored even worse than students in states lacking these programs. Yet subsequent analyses ( Walstad, Rebeck, and MacDonald 2010 ) pointed out that this research was incomplete as it did not account for course content, test measurement, teacher preparation, and amount of instruction. These points were underscored by Tennyson and Nguyen (2001) who revisited the Jump$tart data by looking more closely at state education requirements for personal finance education. They concluded that when students were mandated to take a financial education course, they perform much better than students in states with no personal finance mandates. Accordingly, there is reason to believe that mandating personal finance education may, in fact, be effective in increasing student knowledge—but only when it requires significant exposure to personal finance concepts.

It is likewise risky to draw inferences without knowing about the quality of teaching in these courses. For instance, Way and Holden (2009) examined over 1,200 K–12 teachers, prospective teachers, and teacher education faculty representing four U.S. census regions, along with teachers’ responses to questions about their personal and educational backgrounds in financial education. Almost all of the teachers recognized the importance of and need for financial education, yet fewer than one-fifth stated they were prepared to teach any of the six personal finance concepts normally included in the educational rubrics. Furthermore, prospective teachers felt least competent in the more technical topics including risk management and insurance, as well as saving and investing. Interestingly, these are also the concepts that the larger adult population struggles with, as noted above. That study concluded that state education mandates appeared to have no effect on whether teachers took courses in personal finance, taught the courses, or felt competent to teach such a course, consistent with the fact that the states mandating high school financial education did not necessarily provide or promote teacher training in the field.

It would also be valuable to further investigate whether the knowledge scores actually measured what was taught in school and whether students self-selected into the financial education classes. Walstad, Rebeck, and MacDonald (2010) used a quasi-experimental set up to assess a well-designed video course covering several fundamental concepts for both students and teachers. The test they employed was aligned with what was taught in school, and it measured students’ initial levels of understanding of personal finance so as to capture improvements in financial knowledge. Results indicated a significant increase in personal finance knowledge among the ‘treated’ students, suggesting that carefully crafted experiments can and do detect important improvements in knowledge. This is an area that would benefit from additional careful evaluative research ( Collins and O’Rourke 2010 ).

Compared to the research on schooling, evaluating workplace financial education seems even more challenging. There is evidence that employees who attended a retirement seminar were much more likely to save and contribute to their pension accounts ( Bernheim and Garrett 2003 ). Yet those who attended such seminars could be a self-selected group, since attendance was voluntary; that is, they might already have had a proclivity to save.

Another concern is that researchers have often little or no information on the content and quality of the workplace seminars. A few authors have measured the information content of the seminars ( Clark and D’Ambrosio 2008 ; Lusardi, Keller, and Keller 2008 ) and conducted pre- and post- evaluations to detect behavioral changes or intentions to change future behavior. Their findings, including in-depth interviews and qualitative analysis, are invaluable for shedding light on how to make programs more effective. One notable recent experiment involved exposing a representative sample of the U.S. population to short videos explaining several fundamental concepts including the power of interest compounding, inflation, risk diversification, all topics that most people fail to comprehend ( Heinberg, Hung, Kapteyn, Lusardi, and Yoong 2010 ). Compared to a control group who did not receive such education, those exposed to the informational videos were more knowledgeable and better able to answer hypothetical questions about saving decisions. 46 While more such research is needed, when researchers target concepts using carefully-designed experiments, they are more likely to detect changes in knowledge and behavior critical for making financial decisions.

A related challenge is that it may be difficult to evaluate empirically how actual workers’ behavior changes after an experimental treatment of the type just discussed. Goda, Manchester, and Sojourner (2012) asked whether employee decisions to participate in and contribute to their company retirement plan were affected by information about the correlation between retirement savings and post-retirement income. Since the computation involves complex relationships between contributions, investment returns, retirement ages, and longevity, this is an inherently difficult decision. In that study, employees were randomly assigned to control and treatment groups; the treatment group received an information intervention while nothing was sent to the control group. The intervention contained projections of the additional account balance and retirement income that would result from additional hypothetical contribution amounts, customized to each employee’s current age. Results showed that the treatment group members were more likely than the control group to boost their pension contributions and contribution rates; the increase was an additional 0.17 percent of salary. Moreover, the treatment group felt better informed about retirement planning and was more likely to have figured out how much to save. This experiment is notable in that it rigorously illustrates the effectiveness of interventions—even low-cost informational ones—in increasing pension participation and contributions. 47

Very promising work assessing the effects of financial literacy has also begun to emerge from developing countries. Frequently analysts have focused on people with very low financial literacy and in vulnerable subgroups which may have the most to gain. Many of these studies have also used the experimental method described above, now standard in development economics research. These studies contribute to an understanding of the mechanisms driving financial literacy as well as economic advances for financial education program participants. One example, by Carpena, Cole, Shapiro, and Zia (2011) , sought to disentangle how financial literacy programs influence financial behavior. The authors used a randomized experiment on low income urban households in India who underwent a five-week comprehensive video-based financial education program with modules on savings, credit, insurance and budgeting. They concluded that financial education in this context did not increase respondent numeracy, perhaps not surprisingly given that only four percent of respondents had a secondary education. Nevertheless, financial education did positively influence participant awareness of and attitudes toward financial products and financial planning tools.