Content Search

Philippines

Y It Happened: Learning from Typhoon Yolanda

- Govt. Philippines

Attachments

It took only a few hours on 8 November, 2013 for typhoon (TY) Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) to obliterate towns and cities in the Visayas region, drastically altering lives and reshaping thoughts about disasters and how these impact on the country’s preparedness capacity.

It will take time for the stark reminders of that calamitous event to completely vanish from a people’s collective memory even as the process of healing and recovery has begun.

Part of that process was the need to grapple with the realities of what really happened on the ground and the lessons that could be mined from the experiences of people and communities battered by the typhoon and those who responded to the aid of a stricken land.

One particular articulation of this process was the decision of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) together with other government agencies and the regional offices of the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) to set in motion this project to reflect from the experience with the end in view of improving the disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM) practices, systems, and policies in the country.

It specifically aimed to: 1) document the Yolanda experience (including good practices and/or case stories) using the four thematic areas as a general framework; 2) identify gaps under the existing DRRM set-up, mechanisms, and policies vis-à-vis RA 10121 and the National DRRM Framework Plan; 3) extract key lessons which will serve as inputs to the recovery plan and possible revisions needed in the existing set of DRRM policies, plans, and programs in the country; and 4) identify and share key learnings and challenges with the wider international DRRM community, particularly in the ASEAN.

The concept of the project called, “Learning from Typhoon Yolanda” pointed out that, ‘The impact of the disaster highlighted a number of gaps in the existing DRRM (Disaster Risk Reduction and Management) system and set of capacities from the national to the local DRRM councils and related institutions and/or organizations.’

It further said, ‘With this and other typhoons of similar strength, key stakeholders, especially members of the local and international communities, civil society organizations, local government units, and national government agencies need to reflect on what happened and identify how best they can work together and build back forward, not only in the areas hit by Yolanda, but more importantly, in the institutional mechanisms, policies, and programs so that the country can better reduce the risks of disasters to its people, especially the most vulnerable.’

The framework and methodology in putting together this modest volume, which were anchored on the four thematic areas of the DRRM law: Prevention and Mitigation, Preparedness, Response, and Rehabilitation and Recovery, underlines the comprehensive scope of the project despite the challenge of a short time frame.

According to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Framework (NDRRMF), through the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Plan (NDRRMP), the country will have “safer, adaptive, and disaster resilient communities towards sustainable development” to be achieved through the four mutually reinforcing thematic areas earlier mentioned.

The data-gathering process for this project essentially adhered to the proposition that each thematic area has its own long-term goal which, when put together, will lead to the attainment of the country’s DRRM goal.

The research was also guided by the following definitions of the four thematic areas in relation to priorities:

Prevention and Mitigation provides key strategic actions that give importance to activities revolving around hazards evaluation and mitigation, vulnerability analyses, identification of hazard-prone areas, and mainstreaming DRRM into development plans. It is based on sound and scientific analysis of the different underlying factors which contribute to the vulnerability of the people and eventually, their risks and exposure to hazards and disasters.

Preparedness are the key strategic actions that give importance to activities revolving around community awareness and understanding, contingency planning, conduct of local drills, and the development of a national disaster response plan. Risk-related information coming from the prevention and mitigation aspect is necessary for the preparedness activities to be responsive to the needs of the people and to the situation on the ground. Also, the policies, budget, and institutional mechanisms established under the prevention and mitigation priority area will be further enhanced through capacity-building activities and development of coordination mechanisms. Through these, coordination, complementation, and interoperability of work in DRRM operations and essential services will be ensured. Behavioral change created by the preparedness aspect was eventually measured by how well people responded to the disasters. At the frontlines of preparedness are the local government units, local chief executives, and communities.

Response refers to activities during the actual response operations: from needs assessment and search and rescue to relief operations and early recovery. The success and realization of this priority rely heavily on the completion of the activities under both prevention and mitigation and preparedness aspects including, among others, the coordination and communication mechanisms. On-the-ground partnerships and vertical and horizontal coordination work among key stakeholders will contribute to successful disaster response operations and its smooth transition towards early and long-term recovery work.

Rehabilitation and Recovery cover areas like employment and livelihoods, infrastructure and lifeline facilities, and housing and resettlement, among others. These are recovery efforts done when people are already outside of the evacuation centers.

Although the stories that had emerged from the datagathering process did not cover the fourth thematic area given the limited coverage of the research, a number of areas demonstrated initial gains in rehabilitation and recovery

Related Content

Fao philippines newsletter - 2016 issue 1, philippines humanitarian bulletin issue 24 | 1 – 31 may 2014, philippines typhoon haiyan response - appeal phl131 revision 1, humanitarian implementation plan (hip) philippines (echo/phl/bud/2013/91000) last update: 17/12/2013 version 4.

Journal of Nursing Education and Practice International Peer-reviewed and Open Access Journal for the Nursing Specialists

Journal Metrics

Google-based Impact Factor (2019): 7.86

h-index (August 2019): 29

i10-index (August 2019): 194

h5-index (August 2019): 19

h5-median(August 2019): 27

- Other Journals

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

- Announcements

- Recruitment

- Author Guidelines

- Ethical Guidelines

Experiences with Typhoon Yolanda: The voices of young survivors revealed

Journal of Nursing Education and Practice

ISSN 1925-4040 (Print) ISSN 1925-4059 (Online)

Copyright © Sciedu Press To make sure that you can receive messages from us, please add the 'Sciedupress.com' domain to your e-mail 'safe list'. If you do not receive e-mail in your 'inbox', check your 'bulk mail' or 'junk mail' folders.

- COVID-19 Full Coverage

- Cover Stories

- Ulat Filipino

- Special Reports

- Personal Finance

- Other sports

- Pinoy Achievers

- Immigration Guide

- Science and Research

- Technology, Gadgets and Gaming

- Chika Minute

- Showbiz Abroad

- Family and Relationships

- Art and Culture

- Health and Wellness

- Shopping and Fashion

- Hobbies and Activities

- News Hardcore

- Walang Pasok

- Transportation

- Missing Persons

- Community Bulletin Board

- GMA Public Affairs

- State of the Nation

- Unang Balita

- Balitanghali

- News TV Live

Five years later, Yolanda survivors light the way for the rest of the country – and the world

Today, we remember the over 7,000 people whose lives were lost when exactly five years ago, Super Typhoon Yolanda struck central Philippines.

We remember the countless lives and communities that were forever changed by the super typhoon.

But today, too, we honor the millions of Yolanda survivors who remind us what can be done to not only survive but even thrive in the midst of adversity.

There is the small, off-grid community of Sulu-an Island in Guiuan, Eastern Samar — the first community hit by Typhoon Yolanda — beckoning aspirations for a community that will be energized by the powers of the sun and the wind.

It is the local women’s group Sulong Sulu-an (Forward Sulu-an) holding Zumba dance classes with the help of solar-powered speakers, baking bread under solar-powered lights, going door-to-door asking neighbors how much energy do they need to power their households and island barangay, and setting up their own solar home systems that show us what climate resiliency truly means.

Guiuan’s Bantay Dagat (Sea Patrol) is constructing a solar-powered guardhouse to protect its marine reserves, which are showing signs of recovery from the devastation of the typhoon. It is their townsfolk rediscovering all the ways to cook and eat their indigenous rootcrop, the palawan, which they found to be a reliable substitute for rice especially in the aftermath of Yolanda. We also honor today 300 Solar Scholars mostly from Yolanda-affected areas — Samar, Leyte, Eastern Samar, and Iloilo — as well as communities from Rizal, Laguna, and Cagayan who have also been affected by other typhoons.

They are ordinary citizens as well as community leaders, local government officials, and local development workers who are now integrating community disaster preparedness and response interventions with renewable energy solutions.

Having experienced firsthand how difficult it is to seek outside help without electricity, the Solar Scholars learned how to power their community command posts, evacuation centers, and health centers with TekPaks, portable solar-powered devices designed and built by Yolanda survivors, to provide immediate light and charging needs in times of emergencies.

Today is also a day to honor the members of the RE-Serve Humanitarian Corps, a volunteer group mostly composed of Yolanda survivors who are trained to provide solar power to humanitarian and emergency responders.

Together, the Solar Scholars and members of the RE-Serve Humanitarian Corps are lighting the way in harnessing renewable energy not just for emergency response but for their communities’ development. They continue to pay it forward by training other people affected by typhoons or dealing with the lack of electricity in their own communities.

Recently, twenty participants from Marabut, Samar and Tacloban were trained as Solar Scholars by a pool of women from the RE-Serve Corps and former Solar Scholar graduates. This latest batch of Solar Scholars, most of whom are also women, led the evacuation drill of the coastal town of Marabut two weeks ago.

“Women have an important role in lighting up our homes and our communities. We have proven in our organization that solar power is useful not only in times of disasters like Yolanda but even in everyday life,” said Lorna Ortilla dela Peña, president of the Marabut Women’s Federation.

A previous Solar Scholar trainee, she was one of the facilitators of the latest Solar Scholars training.

“Houses in upland areas with no electricity still heavily rely on their solar lamps, and everyone uses them during brownouts. I wanted to learn more about solar power to help people in my community and I am glad to pass on my knowledge to other women,” she added.

Last month, two RE-Serve members who are Yolanda survivors led a Solar Scholars training of Cagayan locals affected by Typhoon Mangkhut (Ompong).

“As a survivor of Super Typhoon Yolanda, I was prepared to help survivors of Ompong... I thought at first that they would be more prepared than us because they experienced Typhoon Lawin just two years ago,” according to Glinly Alvero, a RE-Serve Humanitarian Corps volunteer and ICSC technical officer.

“But some areas lacked the basic preparations and knowledge regarding disaster response. I am quite saddened because this means that the whole country is still ill prepared,” he added, while lamenting the limited options for communities affected by Mangkhut.

The people of Suluan, Nanay Lorna, Glinly, and several other Yolanda survivors whom we have had the privilege of knowing and working with are fully aware that they remain vulnerable not just to extreme weather events such as Yolanda but also to the creeping impacts of climate change such as increasing temperatures, sea level rise, and ocean acidification.

“Even if no one talks about climate change we feel its effects here,” said Jocelyn Naing, a barangay health worker from Suluan. “This summer the water in the well tasted like the sea,” Socorro Quiminales, a mother also from Suluan, told us.

Rene Basilenes, a fisherfolk from Suluan, told us it was harder to catch fish nowadays unlike in previous years. His fellow fisherfolk Virgilio Loyola said he has noticed how the seawaters inch ever closer to their homes.

Today, we honor their and other survivors’ grit, resilience, and generosity of spirit. We honor their will to survive and thrive on the frontlines of a warming world.

Today, we recommit ourselves to helping communities like theirs adapt to the impacts of climate change and transition to cleaner and more reliable energy. — LA, GMA News

Denise M. Fontanilla is the associate for policy advocacy of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities, a climate and energy policy group.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Typhoon “Yolanda” Experience of Leyte, Philippines and the Recovery Strategy of Eastern Visayas State University

More than the great casualty incidence, Typhoon “Yolanda” rendered nearly 200 thousand families totally homeless and brought damage to both public and private resources and assets resulting to infrastructure gridlocks and economic setbacks. The main objective of Leyte’s Rehabilitation and Recovery Plan is to bring back the economic and social conditions of the people, at least, at pre-typhoon level and a higher level of disaster resiliency. The sectors include outputs on infrastructure and utilities, housing, health facilities, services, livelihood assistance in agriculture and marginal sectors, and employment opportunities, and support to social welfare services and the environmental, gender and development and the overall poverty alleviation cross cutting themes. For Eastern Visayas State University, it needs at least $18 million to finance mostly the construction of temporary shelter/classrooms, infrastructure restoration/repairs in all campuses, structural retrofitting, equipment procurement and debris/waste materials management. The proposed facilities will entail the integration of disaster-resilient character, with a focus on the functionality, aesthetics, environment-friendly and sustainability of designs.

Related Papers

Pauline Eadie , Maria Ela Atienza , Professor May Tan-Mullins

This working paper assesses what ‘building back better’ really means and how the rhetoric measures up to reality in Leyte. Drawing on fieldwork data we focus on housing, risk reduction and resilience building. These key themes are linked to ‘adaptation’. Successful adaptation is key to moving beyond the pre-disaster vulnerabilities that exposed so many people to Yolanda’s wrath. We address adaptation in the material and social sense as building back better is about sustainable communities as well as physical reconstruction. This paper focuses on housing, as adequate shelter is fundamental to human dignity and well-being and a crucial pre-requisite for the regular functioning of community life. This paper questions whether building back is enough. If economic and social conditions can only be restored, and not improved, to what extent can a higher level of disaster resilience be achieved? We interrogate the notion of building forward, rather than back, and argue that resilience incorporates the adaption, rather than just restoration, of homes and communities. This paper identifies both material adaptations have been made and outstanding adaptations. In social terms we address the problems that face communities that have been disrupted by relocation as a measure of whether these communities can be sustainable and ‘resilient’ over the longer term. We incorporate the self-assessments of ‘building back better’ that we heard in these communities and argue that ‘better’ is actually hard to quantify.

Pollack Periodica

Rowell Ray Shih

Michael Padilla

In 2013 Typhoon Haiyan, the largest typhoon ever recorded in the Philippines, devastated several portions of the country. This resulted in more than 7,000 deaths and thousands of people were misplaced or were made homeless. The aim of this study is to design and produce a transitional shelter prototype, for the victims of typhoon Haiyan. The shelter is affordable, easy to construct using basic tools and that can provide maximum space for a family of five while being able to withstand an onslaught on another incoming typhoon. Furthermore, this paper presents a design concept for a transitional shelter incorporating the Bent Method of construction while only using locally sourced coco lumber and actual validation on a full scale prototype. In order to achieve this objective, site analysis as well as consultations and interviews with the victims were being done and the results evaluated. Second, the conceptual designs as well as the method are presented to the local government and the ...

Infrastructure Risk Assessment and Management

Maria Eduarda Dias

Sudhir Kumar

The Philippines was badly impacted by Typhoon Haiyan on 8 November 2013, which led to several thousand deaths, loss of properties and livelihoods. The Government of Philippines along with development partners undertook massive response and relief exercise, currenlty recovery and reconstruction is underway. This ongoing recovery and reconstruction is mamooth and challenging and has potential to offer a number of lessons to future recovery managers and policy makers. This paper has explored some of these challenges and its significance

The Relocation Site in Brgy. 105 Sn. Isidro, Tacloban City for Typhoon Yolanda Victims: A Beneficiaries’ Perspective

Rannie C O N D E S Agustin

The relocation site in Brgy 105 Sn. Isidro, Tacloban City for the victims of typhoon Yolanda is described by this study to evaluate the resiliency level of the resettlement area for community development. The study gathered information through survey-interview with randomized samples from the population of resident beneficiaries of housing programs in the relocation site. The accounts were categorized and themed into composite indicators framed in SoVI developed by Susan Cutter. Data and information are also provided by PSA and City Planning Office cited in Riel " s (2017) study. The study concluded that the resiliency level of relocation site in Brgy 105 Sn. Isidro, Tacloban City, in particular and the whole barangay in general, as Highly Vulnerable to disaster. Families and individuals for relocation must not be alienated from their socio-cultural background, interests and economic needs. The original settlers are not independent neither unaffected by the relocated group (Yolanda victims) of population and vice versa. Resiliency of a community or society is associated with economic development and general well-being of the population. 2

Disaster medicine and public health preparedness

Christopher Shane M. Gonzales

Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines in November 2013 and left a trail of destruction. As part of its emergency response, Médecins Sans Frontières distributed materials for reconstructing houses and boats as standardized kits to be shared between households. Community engagement was sought and communities were empowered in deciding how to make the distributions. We aimed to answer, Was this effective and what lessons were learned? A cross-sectional survey using a semi-structured questionnaire was conducted in May 2014 and included all community leaders and 269 households in 22 barangays (community administrative areas). All houses were affected by the typhoon, of which 182 (68%) were totally damaged. All households reported having received and used the housing material. However, in 238 (88%) house repair was incomplete because the materials provided were insufficient or inappropriate for the required repairs. This experience of emergency mass distribution of reconstruction or repair m...

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS)

Glenne Lagura

This case study aimed to determine the rehabilitation program for typhoon Pablo victims in the province of Davao del Norte. Using the purposive sampling technique, twelve (12) informants were interviewed in three (3) municipalities, namely the municipality of Kapalong, San Isidro, and Talaingod, Davao del Norte covering three (3) commodities such as; banana, cacao, and coffee rehabilitation program. A qualitative research instrument was used to capture all data relevant to their experiences, challenges, and overcoming strategies. Thematic analysis by Creswell (2009) was employed to analyze the data. Under the experiences, the result revealed the following themes; living comfortably after the typhoon, damaged farmlands and crops, income loss in agriculture, generation of alternative income and employment, the existence of disaster resiliency and management, provision of inputs, and cash assistance and implementation of the rehabilitation program. Furthermore, the challenges experienced by the victims are climate change, market instability, financial incapacity, lack of information and education, low-quality seedlings and high cost of production, lack of crop insurance, and delayed distribution of seedlings. The overcoming strategies they identified were as follows; develop a positive attitude toward family welfare, develop ways for sustainable farming, availing of the loan program, and intensify coordination for assistance. Finally, the success stories revealed the following cluster; development of self-reliance and perseverance, recovery as a result of hard work and assistance, development of a positive outlook for the future, and government response helped to expedite rehabilitation. The implementation of the typhoon Pablo rehabilitation program must couple with appropriate policy frameworks and political and financial support for the farmers to bridge the gap. Thus, creating a sustainable agricultural program and planning a disaster response will benefit the farmers in the long term. Farmers, scientists, and institutions continually aim to uncover techniques that boost crop yields, improve agricultural productivity, minimize loss due to disease, insects, and disasters, create more efficient equipment, and improve food quality overall. Lastly, the Department of Agriculture, Local Government Units, National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council, Non-government Organizations, and other concerned agencies can help the farmers live a decent life by providing appropriate intervention and assistance that promote the interests and needs of the agricultural sector.

Reinna Bermudez

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

Livelihood and vulnerability in the wake of Typhoon Yolanda: lessons of community and resilience

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2020

- Volume 103 , pages 211–230, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Pauline Eadie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7866-2720 2 ,

- Maria Ela Atienza 1 &

- May Tan-Mullins ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0236-5145 3

36k Accesses

12 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Livelihood strategies that are crafted in ‘extra-ordinary’ post-disaster conditions should also be able to function once some semblance of normalcy has resumed. This article aims to show that the vulnerability experienced in relation to Typhoon Yolanda was, and continues to be, directly linked to inadequate livelihood assets and opportunities. We examine the extent to which various livelihood strategies lessened vulnerability post-Typhoon Yolanda and argue that creating conditions under which disaster survivors have the freedom to pursue sustainable livelihood is essential in order to foster resilience and reduce vulnerability against future disasters. We offer suggestions to improve future relief efforts, including suggestions made by the survivors themselves. We caution against rehabilitation strategies that knowingly or unknowingly, resurrect pre-disaster vulnerability. Strategies that foster dependency, fail to appreciate local political or ecological conditions or undermine cooperation and cohesion in already vulnerable communities will be bound to fail. Some of the livelihood strategies that we observed post-Typhoon Yolanda failed on some or all of these points. It is important for future policy that these failings are addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Vulnerability and Disaster in Thailand: Scale, Power, and Collaboration in Post-tsunami Recovery

Community Resettlement in Louisiana: Learning from Histories of Horror and Hope

Sustainable Development Through Post-Disaster Reconstruction: A Unique Example in Sri Lanka

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Livelihood can be threatened by a complex array of issues such as disasters and wars, which could deprive households of productive assets and access to markets, and potentially disrupt livelihood related mutual support mechanisms that often exist in poor communities. In this article, we argue that strategies to restore livelihood after a disaster must be devised so that they can function effectively under ‘ordinary’, as opposed to ‘extraordinary’ conditions (or times). Ordinary and extraordinary are not polar opposites; they are points on a shifting and complex matrix of socio-economic life and the impact of disasters. Ordinary conditions may include, but are not limited to, exposure to various anticipated risks such as seasonal storms and flooding, inadequate shelter, discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, age or gender, limited livelihood related capability or governmental inadequacy. These are at times structural and consistent conditions that could happen on a regular basis. Disasters such as super typhoon Yolanda (international name Haiyan) are considered to be extraordinary. They are extreme in terms of their sheer scale and severity, are unusually disruptive and result in unanticipated impacts.

In the aftermath of Typhoon Yolanda thousands of aid workers arrived in the disaster zone and millions of dollars in foreign aid poured into the local economy in support of the humanitarian relief and rehabilitation effort. Many agencies stayed for up to 2 years, some for longer, creating new opportunities for business, investment and local employment but demand also increased for local goods and service, inflating prices and creating jobs (Secret Aid Worker 2015 ). However, when aid agencies move on, and the post-disaster economic bubble Footnote 1 has run its course, a return to socio-economic ‘normalcy’ may be suboptimal, impossible or hard to quantify. Nevertheless, livelihood strategies created in the aftermath of a disaster should still be viable in ‘ordinary’ circumstances. For livelihood initiatives to be truly sustainable, they should be capable of reducing vulnerability over the longer term and making the ‘ordinary’ better.

Human vulnerability is a multi-dimensional and dynamic condition. Age, gender, disability, sexuality, ethnic difference, locality and levels of wealth can all influence how vulnerable people are to specific threats and how these threats are perceived and experienced. Poor individuals or communities may not, on the face of it, appear insecure as they are functioning and their vulnerability may be latent. However, natural hazards can expose this latent vulnerability that poor communities live with on a daily basis. When this exposure is sudden, as in the case of major typhoons or earthquakes, the impact of the event dictates that the event itself and the subsequent relief effort is presented in ‘extraordinary’ terms.

This was the case when Typhoon Yolanda struck the Eastern Visayas region of the Philippines on 8 November 2013. It was one of the strongest typhoons ever to make landfall with wind speeds up to 315 kms per hour and a strong surge that reached six metres in places. More than 6000 people died, 1785 were reported missing and 28,626 were injured (National Operational Assessment of Hazards, n.d.). The total number of people affected by Typhoon Yolanda, in relation to their livelihood, environmental and food security, was approximately 16 million. The livelihoods of 5.9 million people were ‘destroyed, lost or disrupted’ (OCHA/UNEP 2014 : 5) by Typhoon Yolanda.

Building on the earlier work of Cannon et al. ( 2003 ), we argue that post-disaster livelihood strategies that are informed by a central reference point of vulnerability (during the ‘ordinary’ times) could help build more resilient futures. We argue that ex ante livelihood ‘buffers’ (Marschke and Berkes 2006 ; Scoones 1998 ) could help reduce vulnerability and that these buffers should be mainstreamed into disaster risk reduction (DRR). We have chosen to focus on livelihood because this issue was central to the rehabilitation efforts post-Typhoon Yolanda and is more broadly a key driver of sustainable post-disaster recovery. In connection with the other related literature, livelihood is one of two (the other being housing) aspects of recovery that ‘play a critical role in the perception of affected individuals about their general recovery after disasters’ (Taheri Tafti and Tomlinson 2015 : 168).

The communities examined in this article are all located in the adjacent Local Government Units (LGUs) of Palo, Tanauan and Tacloban City, in the Eastern Visayas region (also known as Region VIII) of the Philippines. This region bore the brunt of Typhoon Yolanda in November 2013. Governance in the Philippines is devolved through a system of LGUs, namely provinces, cities, municipalities, and barangays (the smallest political-administrative units) run by elected officials. LGUs have various powers that are devolved from the national government under the 1991 Local Government Code (Brillantes 1998 ). Palo is a third class municipality and Tanauan is designated second class; government classification is based on income. Tacloban is a highly urbanised city with a population of over 242,089 in 2015 (Philippines Statistics Authority 2016 ) and an annual income over 50 million PHP (constant price using 1991 as base year).

The Visayas islands are home to some of the poorest provinces in the Philippines Footnote 2 . The three areas were chosen as the focus of this study as they were at the centre of a massive and prolonged international relief effort. They are not conflict zones; however, many coastal dwellers lived ‘close to the subsistence level and [were] thus structurally positioned at the edge of socio-economic disaster’ (Siar 2003 : 272). In this case, socio-economic disaster was triggered by a ‘natural disaster’, Typhoon Yolanda. An assessment of the extent to which relief strategies reduced or increased vulnerability via livelihood, is one useful way of testing whether disaster relief strategies really managed to foster resilience after Typhoon Yolanda. As vulnerability is understood and experienced in many different ways, this article draws on a wide range of primary survey and interview data gathered in our chosen communities.

This article first outlines our data gathering strategies and elaborates on vulnerability as a conceptual framework. We then summarise the different concepts such as livelihood, resilience, disasters and vulnerability and their relation to each other. We argue that the vulnerability experienced in relation to Typhoon Yolanda was, and continues to be, directly linked to inadequate livelihood assets and opportunities. The next section examines the pre-disaster vulnerability that existed during ‘ordinary’ conditions. This is followed by an assessment of how post-disaster interventions during ‘extraordinary’ circumstances contributed, or did not contribute, to resilience and lessening of vulnerability. The final section summarises our findings and we conclude by cautioning against rehabilitation strategies that knowingly or unknowingly, resurrect pre-disaster vulnerability. Strategies that foster dependency, fail to appreciate local political or ecological conditions or undermine cooperation and cohesion in already vulnerable communities will be bound to fail.

2 Data gathering

In this article, we use a comparative and mixed methods approach using quantitative and qualitative data. Evidence is drawn mostly from 20 barangays of comparable size across three LGUs: eight in Tacloban City, six in Palo and six in Tanauan. The uneven sample size across the LGUs relates to the differing size, and hence number of barangays, within each LGU. Assessing post-disaster activity across space at the barangay level allowed us to compare what strategies worked better or worse in similarly impacted, but different, localities in terms of post-disaster resilience building. This is important as community resilience building is best understood from the bottom up in order to avoid ‘disaster management interventions [that] have a propensity to follow a paternalistic mode that can lead to the skewing of activities towards supply rather than demand’ (Manyena 2006 : 438).

Coastal geography alone dictated our choice of barangays Footnote 3 , and we had no prior assumptions about the degree of social cohesion or effective leadership and capacity building within each barangay. This paper is based on the premise that there was great value in information drawn directly from local ‘communities’ that had lived experience of the disaster and its aftermath. We treat communities as being a group of people living within the geographically and politically defined area of a barangay. These communities are linked by family ties and embedded interaction between neighbours, especially where populations are stable. However, such communities do not operate in isolation. Networks of social interaction and joint action that impacted upon these communities operated at a number of levels including locally, nationally and internationally. The idea of community is important as without ‘community participation, disaster relief often inadvertently rebuilds […] structures of vulnerability’ (Bhatt and Reynolds 2012 : 74).

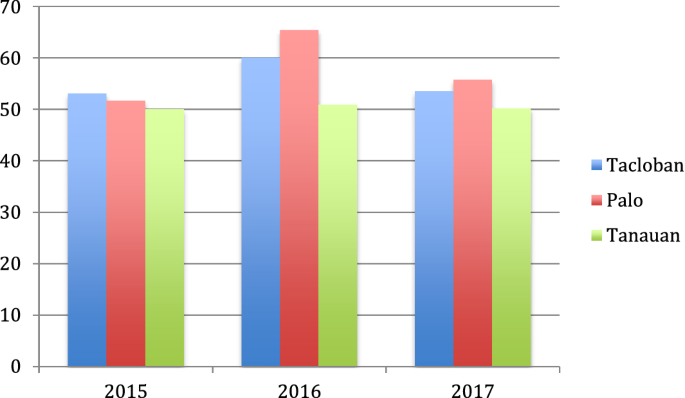

Vulnerability is a material and social condition and, to a certain extent, subjective. Therefore, we aimed to gather a broad range of data on the material and social experience of rehabilitation as systematically as possible. We interviewed a sample of the population large enough to allow for the cross-checking of responses and conducted about 800 household surveys annually in 2015, 2016 and 2017. This allowed us to identify general trends in how the rehabilitation efforts were perceived and experienced across time and space and teased out the nuances of power relations between the different stakeholders. The data cited in this paper refers only to the survey responses that directly address livelihood. We instructed our fieldworkers to survey an equal balance of men and women; nevertheless, our respondents were predominately female: 61 per cent in 2015, 74.7 per cent in 2016 and 75 per cent in 2017. As our surveys were conducted during daylight hours this gender imbalance was indicative that it was predominantly women who were at home during the working day.

Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with a range of governmental and non-governmental stakeholders over 4 years from 2014 to 2018. We interviewed each barangay captain (or representative) and mayor annually for the duration of our project. Twenty-four focus group discussions with various sectors including women, the elderly, youth, persons with disabilities and mixed groups, across the three LGUs were held over 3 years. We also identified two families in each barangay, one most affected and one least affected, that were willing to be interviewed year on year. By selecting 20 most affected and 20 least affected families, we aimed to establish the factors that helped or hindered disaster recovery given their similar but perhaps different experiences. We asked every family the same questions. By interviewing 40 families in a semi-structured and systematic fashion, we aimed to go beyond mere anecdotal evidence.

The virtue of gathering evidence over time is that we were able to monitor first-hand the extent to which relief operations ameliorated the vulnerability of communities beyond the initial emergency phase. We were able to go back to the same communities and the same respondents to see whether their situation had improved or changed and what the primary obstacles were to their rehabilitation. We were also able to observe the shift in activity when many international aid agencies left and tease out the sustainability of these livelihood strategies in both extraordinary and ordinary conditions. The production of both quantitative survey data and qualitative interview data allowed us to compare quantitative trends with rich empirical data from interviews. Gathering data from a range of stakeholders allowed us to assess how livelihood strategies were both produced and applied and to compare the stated aims and objectives of the strategies with how they were actually experienced.

We also took note of the existing institutional governance structures. While the form of government is unitary, devolution was established in the Philippines via the 1991 Local Government Code (Republic Act No. 7160). The Code devolved wide-ranging responsibilities to LGUs, including disaster response and management (Atienza et al. 2019 ). Furthermore, the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010 (Republic Act No. 10121), in setting up the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Framework as well as the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), puts in the frontline both the national government and LGUs (Eadie 2019 : 93–94). LGUs are mandated to have their own local DRRM budgets, plans, and offices. The national DRRM framework also enables various government agencies at various levels not only to coordinate with each other but with civil society organizations as well as international and foreign bilateral agencies.

A consideration of the prevailing governance structures helps us to assess some of the institutional factors that affected the sustainability of the livelihood strategies introduced in the three areas that we studied. It is also useful to reflect on whether there were problems with the governance structures themselves or only in policy implementation.

3 Resilience, livelihood, disaster and vulnerability

Resilience has been debated across disciplines in physical/material and social terms. Footnote 4 The word resilience is derived from the Latin word resilio meaning to leap or spring back. It can be defined as ‘the capacity of any entity—an individual, a community, an organisation, of a natural system—to prepare for disruptions, to recover from shocks and stresses, and to adapt and grow from a disruptive experience’ (Rodin 2015 : 3). Resilience does not just relate to the ability to deflect and counter threats; it is also about physical and social adaptation. Therefore, resilience can be equated to capabilities. Ideally survivors should have the capabilities to reduce their own vulnerability and work towards a resilient future. Resilience may be subjective and ‘comparable disasters could generate quite different articulations of resilience from similarly affected communities’ (Eadie 2019 : 98). Vulnerability and resilience can also coexist. From the outside, vulnerable communities may look like their ability to take action is constrained but the various hardships faced on a daily basis can mean that resilience is inbuilt. People are used to coping with living in close proximity to each other, economic stress and environmental threats. Therefore, coping strategies and ‘psychological resilience’ (Usamah et al. 2014 : 187) are quickly activated during disasters.

Livelihood, as a means of resilience, needs to be understood in a framework of changing social, political, economic and environmental contexts (Davidson-Hunt and Berkes 2003 ; de Haan and Zoomers 2005 ; Delisle and Turner 2016 ). Indeed, the notion of livelihood itself should be seen in context: ‘livelihood is a larger, more universal and more useful concept for seeing what best to do, encompassing as it does for many of the poor so much more than the employment of a job, which for many is not and cannot be a reality’ (Chambers 1995 : 183). Livelihood is not just a salary or a job; it is about the various ways that individuals and communities sustain themselves. Livelihood is commonly defined as, ‘the capabilities, assets (both natural and social) and activities required for a means of living: a livelihood is sustainable when it can cope with and recover from stresses and shocks, maintain or enhance capabilities and assets, both now and in the future, while not undermining the natural resource base’ (Chambers and Conway 1992 : 7).

Livelihood is socially and ecologically situated. How intangible assets such as skills and social support, and tangible assets such as finance and ecological resources are accessed is an important determinant of livelihood (Bebbington 1999 ; Sok and Xu 2015 ). Many of the world’s poor secure a living via the creation of multiple strategies that cannot be quantified on the basis of income alone. The poor exist in conditions that are ‘local, complex, diverse and dynamic’ (Chambers 1995 : 173) and inevitably impact on the lived experience of the search for livelihood.

Livelihood decisions may involve meeting immediate needs even if this increases future vulnerability, e.g. going into debt, skipping education to go to work or engaging in unhealthy or dangerous work. These trade-offs have to be seen within the context that they are made and how people rationalise their own circumstances, ‘the constraints under which they make these decisions and the power relations at play’ (Bebbington 1999 : 2033). Wealth, access to credit and productive assets such as land (Borras and Franco 2005 ), institutional policy (Scoones 2009 : 176–183), human ingenuity, skills, training, equipment and social networks are important capability indicators. Issues such as gender (Angeles and Hill 2009 ; Gaillard et al. 2015 ; Siar 2003 ), disability (Tabuga and Mina 2011 ; Yamagata 2015 ), culture and social norms can also dictate how livelihood assets are accessed and utilised. The livelihood opportunities of women may be compromised because they are expected to take on unpaid care work that impact on their ‘share in the distribution of resources post-disaster because their productive and reproductive contributions remain undervalued, uncounted and unpaid’ (Tanyag 2018 : 566). These issues present us with a set of complex indicators that are not always easy to measure, isolate or replicate.

Livelihood activities play out in different ways in different places. Rural livelihoods are likely to involve a combination of ‘different activities in a complex bricolage or portfolio of activities’ (Scoones 2009 : 172) that are closely connected to the natural environment and the rhythm of the seasons. However, the focus on capabilities and assets in relation to shocks and stresses also translates to the urban environment. The variables that affect rural dwellers such as access to land, the depletion of open access resources such as fisheries, shelter and credit, skills and training and a government that can be held to account for the well-being of the population play out in different ways in the urban context, but they are still relevant.

In relation to shocks and stress Ian Scoones suggests that livelihood ‘buffers’ can be created if (a) livelihood resources are kept in reserve, (b) single and multiple livelihood activities can be diversified and realigned so that if a particular activity or complementary set of activities come under threat, alternative livelihood options are still available, (c) risk to livelihood is ‘pooled’ so the threats are minimised, and (d) resilient systems are built so that shocks and stresses have less impact (Scoones 1998 : 10). These strategies are laudable in relation to building sustainable livelihoods; however, such interventions are seldom easy in poor communities that may be functioning at a bare level of existence. Nevertheless, they are sound benchmarks against which vulnerability can be measured.

Such buffers are particularly important in areas prone to disasters and ‘sustainable livelihood’ approaches can provide a valuable opportunity for combining disaster reduction and development interventions in one unifying approach’ (Sanderson 2000 : 51). Sustainable livelihood approaches have typically focused on how human, social, physical, natural and financial capital can be ‘assessed in terms of their vulnerability to shocks and the institutional context in which they exist’ (Morse and MacNamara 2013 : 19). For livelihood to be resilient, it should be adaptable in the face of adverse conditions, and if necessary be realigned or reinvented ex post in the face of sometimes drastically altered socio-economic or ecological realities. Careful attention to the capabilities and assets could help ameliorate future vulnerability and aid disaster recovery.

The United Nations (UN) defines disasters as ‘a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope with its own resources’ (UNISDR 2009 : 9). Environmental events, such as typhoons or earthquakes, are only classed as disasters when populations are seriously overwhelmed by the impact. The social aspect of disasters is a common but important theme in disaster research. Wisner et al. acknowledge that disasters are products ‘of social, political and economic environments because of the way these structure the lives of different groups of people’ ( 2004 : 4). The nature of this interplay is complex, contested and varies widely across time and space, meaning that ‘disasters cannot be understood to be “natural” in any straightforward way’ (Wisner et al. 2004 : 9). Meanwhile, Daniel P. Aldrich highlights social systems and resources that are overwhelmed by disaster. Aldrich defines disasters as ‘event[s] that suspend normal activities and threatens or cause severe, community wide damage’ ( 2012 : 3). The use of the word community is notable as disaster is seen to impact on some sort of collective that is not necessarily the state.

Disasters often have the greatest impact on the most vulnerable populations and ‘disasters occur when natural hazards and human vulnerabilities interact’ (Bacon 2014 : 23). Vulnerability to disasters is heightened by poverty and measures to mitigate and prevent disasters that ignore ‘underlying, hazard independent structural constraints’ (Gaillard et al. 2009 : 126), inevitably ending up treating the symptoms, as opposed to the root causes of vulnerability. Omar D. Cardona defines vulnerability as ‘the physical, economic, political or social susceptibility or predisposition of a community to damage’ ( 2004 : 37). Meanwhile, Bankoff argues that ‘vulnerable populations are created by particular social systems in which the state apportions risk unevenly amongst its citizens’ ( 2003 : 12). Not all poor people are at risk from disasters. Nevertheless, those who live in fragile housing in exposed localities or risky locations and lack access to financial or material safety nets (in other words buffers) are particularly vulnerable to calamities.

Indeed, as indicated by Rigg et al., ‘natural events may appear cruelly random but their impacts, who they affect and how, the degree of resilience that societies and individuals exhibit, and the trajectories of recovery, are far from random’ ( 2008 : 138). As we can see from the above, there is consensus that vulnerability is socially determined. For this reason, an approach to disasters that focuses on vulnerability and widens the discussion to ‘consider context, human rights and security more generally’ (Brown and Westaway 2011 : 333) is of value. For without social change, pre-existing vulnerability is likely to prevail in the aftermath of a disaster. This indicates that to devise sustainable livelihood in ‘extraordinary’ times in the aftermath of disasters, we need to re-evaluate the social injustice and vulnerability in the pre-disaster moments, i.e. the ordinary times.

This means getting ‘back to normal’ after a disaster is both a moving target and not necessarily an ideal state of affairs (Kelman et al. 2016 : S137–S138). This is especially crucial when extreme weather events are arguably the new normal (Mondragon 2015 ; David et al. 2013 ; IPCC 2018 ) in countries where hurricanes, cyclones and typhoons or drought and high temperatures already appear with seasonal regularity. As such livelihood strategies need to be sustainable in environmental as well as socio-economic terms. There is also a tension between the need to devise sustainable livelihood strategies that ameliorate immediate and local shocks and stresses with the bigger picture of climate change. Thus far the literature on mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) and development has tended to focus broadly on agriculture (Trujillo and Bass 2015 ), the physical environment (Chmutina and Bosher 2015 ; Wamsler 2006 ), governance (Tanner et al. 2019 ) and gender (Ginige et al. 2009 ; Khoza et al. 2019 ; Yumarni and Amaratunga 2018 ). A specific focus on the complexity of sustainable livelihood in both the ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’ is lacking. This is where this article will turn to next.

4 Pre-disaster livelihood vulnerability (ordinary conditions)

One day before Yolanda, on 7 November 2013, barangay captains and local government officials were tasked with encouraging people to go to designated evacuation centres or higher ground in anticipation of the coming super typhoon. National government leaders and agencies, through television and radio, warned of the strength of the coming typhoon. Key informants noted that while some followed the warning and evacuated, others remained or decided to stay at home to guard their property. Despite the vulnerability of their housing and coastal location, poor householders chose to stay put in the face of an impending disaster in order to safeguard their scarce possessions, which represented ‘their life’s work and sacrifices’ (Dalisay and de Guzman 2016 : 708–709). The coping strategies for many of the poor when warned of the imminent danger of a major typhoon was for the women and young children to evacuate to storm shelters whilst the men and older boys stay put and guard their houses and scarce possessions. This meant many of the men and older boys perished in the typhoon. This was evidenced by Bernardita Valenzuela, Footnote 5 Head of Tacloban City Information Office and executive assistant to Mayor Alfred Romualdez, who described trying to convince a family to leave:

I asked a fisher family to leave and said that the mayor has sent vehicles for them to go to the evacuation centre. The head of family responded, “Ma’am I cannot leave my house, my belongings and my pig”. His pig is his means of livelihood […] “What is the use of my life if I have no roof over my head and no food to put on the table for my family?” He said, “don’t get angry Ma’am you bring my wife and my daughters” […] He and his sons, they were all washed away (Valenzuela 2015 ).

People also refused to leave because they underestimated the impact of Yolanda. This led to the high casualty rate. We heard the phrase ‘We were used to typhoons, but we did not expect the storm surge’ repeatedly. A combination of past experience and the perceived importance of safeguarding livelihood assets and material goods meant that vulnerable householders were prepared to engage in ‘risky’ behaviour in the face of an incoming disaster. The ‘buffers’ discussed earlier in this article were either weak or absent in some cases. Even though the family above engaged in both fishing and raising a pig, the loss of the pig would have equated to the loss of a significant livelihood asset. In Region VIII as a whole, pre-Typhoon Yolanda (2012) statistics show that 24.9 per cent of the urban population were living in poverty. However, the numbers were much higher for certain groups e.g. 49.2 per cent of farmers, 46.4 per cent of fishermen and 40.4 per cent of self-employed or unpaid family workers (Philippine Statistics Authority 2016 : 2–15) meaning that these groups were potentially more vulnerable to shocks and stresses. This gives credence to the argument that ‘people and their vulnerability or resilience, instead of the physical implications of natural hazards, should be at the core of [disaster] analysis’ (Bambals 2015 : 150). Many people were vulnerable before Typhoon Yolanda and were subsequently left completely destitute in the aftermath of the disaster. Homes and possessions were swept away and family members were lost. The loss of tangible assets such as land, equipment (for example, tools, boats), livestock, crops and manpower from the household had a significant effect on livelihood.

5 Post-disaster livelihood interventions (extraordinary conditions)

USAID estimated that Typhoon Yolanda affected the income stream of 5.9 million, workers ‘as a result of infrastructure damage, lack of access to markets, and disrupted cash flow’ (USAID 2014 : 2). Of those 5.9 million ‘44 per cent (2.6 million) of those affected were engaged in vulnerable employment as own account or contributing family workers with limited income and social security prior to the disaster’ (ILO 2015 : 11). ‘Vulnerable employees’, that is the self-employed who are directly dependent on the profit made from the goods and services produced, are most exposed to sudden and hurtful disruptions to livelihood.

Employment figures in the aftermath of Yolanda remained steady, most likely because of the multiple livelihood programmes available and the opportunities that came with the post-typhoon reconstruction fuelled economic boom. However, 47.7 per cent in 2013 and 50.4 per cent in 2014 of those classed as employed were working less than 40 h a week (Philippine Statistics Authority 2016b : 11.3) meaning that the line between employed and underemployed Footnote 6 was perhaps questionable. Please see the table below for a list of livelihood initiatives mentioned by our informants. The list is non-exhaustive but gives an idea of the kinds of programmes offered by government and other agencies in operation post Yolanda (Table 1 ).

Despite the relatively healthy employment figures detailed above, the predominantly female respondents in the barangays under investigation gave far higher rates of unemployment and underemployment than the official averages for Region VIII. As evidenced in the chart below (Fig. 1 ).

Rate of unemployment based on authors’ survey data. [For full survey results see (Berja 2015 )]

These figures are perhaps indicative that the region wide averages masked significant pockets of unemployment in the most vulnerable communities.

During our first survey round in 2015, 91.2 per cent of our survey respondents indicated that Typhoon Yolanda affected their livelihood. In 2016, 50 per cent reported that sourcing livelihood was more difficult in the time period since Yolanda and by 2017 this had dropped to 38 per cent. But despite this improvement over time 76 per cent in 2015, 82 per cent in 2016 and 83 per cent in 2017 reported that they had received no livelihood assistance or training. Before Typhoon Yolanda, most residents in the areas under investigation were engaged in the manufacturing and services sector, such as working in factories, and as sellers and traders and other labour-based jobs. However, less than half of our survey respondents living below the poverty threshold relied on salaries for their income, 33.2 per cent ran small businesses, 4.3 per cent received financial assistance of some sort, 1.9 per cent lived off a pension with 18.3 per cent citing ‘other’ sources of income. The diversity of activity reported as ‘livelihood’ reinforces the validity of Chambers’ claim ( 1995 : 191) that livelihood is a much more meaningful term than employment when capturing how people make a living. According to Chambers, ‘on livelihood, the strategies of the poor are usually diverse and often complex’ ( 1995 : 192). Consequently, the measurement of monetary income as a determinant of sustainable livelihood may be problematic as income may be fluctuating, fragmented and fail to capture other forms of material exchange. The high level of non-salary income amongst the poor is also indicative that livelihood schemes and entrepreneurial training are extremely important. Our interviewees repeatedly cited lack of livelihood as a source of vulnerability for Yolanda survivors.

5.1 Aid allocation

In the mid-term recovery phase numerous agencies handed out free cash without any need to contribute labour to the projects. This created a competition between the different aid agencies and within communities, as people naturally took the free cash rather than work for it. Free cash can also create a dependency mentality, as people begin to rely on further donations to sustain them. In the longer term, vulnerability cannot be countered by dole outs. It is, therefore, important that aid enables survivors the freedom to pursue efficient, contextually appropriate and sustainable livelihood strategies. In other words, after the initial emergency phase, government agencies and aid agencies should focus on capability building and the building of ‘livelihood’ buffers in order to minimise risk, stabilise livelihood and reduce vulnerability. The failure to diversify was evident in relation to fisheries and coconut farming as detailed below.

Typhoon Yolanda directly affected 39,000 fisher families. Multiplier effects meant that up to 400,000 people, whose livelihoods were indirectly related to fisheries, were affected (ReliefWeb 2014 : 15). The Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) organised a mechanism to monitor the distribution of clearly needed boats. However, we found numerous examples of duplicated aid. Fishermen were favoured recipients of equipment and aid but in some cases individual fisherman received up to three boats (with others not receiving even one), by different donors. Footnote 7 This is because boat donations make good headlines and positive public relations for the donor agencies, which could encourage more donations to that particular agency. Poorly planned over-generosity often results in greater competition among the fisherfolk, as boats were also given to non-fishers. The increase in fishing activity depletes the fishery resources and threatens the sustainability of livelihoods. Alternatively, boats are accepted but lie unused and are simply a waste of much-needed resources.

Many of our interviewees also indicated that there were sectoral preferences on helping fishermen, but very little on farmers, factory workers and people working in the informal sector. The government has come under criticism as farming programs ‘do not necessarily address the issue of agriculture backwardness and underdevelopment that should be the priority of action’ (IBON 2016 ); in other words, the overarching social order remains the same and farmers remain vulnerable. Most farmers affected by Yolanda rely on coconut farming for their livelihood, but most of the trees were destroyed by the storm and it will take several years for coconut seedlings to grow full-term. However, coco farmers received scant assistance. According to some of our informants, farmers need support for alternative crops suitable for the area, alternative livelihoods, as well as support for irrigation and cooperative building. Without this support, farmers are trapped in a cycle of insecurity as they lack the freedom or capacity to build sustainable livelihood solutions.

5.2 Gender and livelihood

Another phenomenon in evidence was that many livelihood options are gender-biased. As evidenced above, livelihood programmes tend to focus on the rehabilitation of fisherfolks, who are usually men. Darina Romero, barangay captain of Barangay Libertad in Palo Footnote 8 , explained that the women in her community:

Want to do a lot more, to bring in income and also make life easier for our community. We would be grateful if there are some kind of livelihood options available to us, such as an investment to buy an oven so we can start a bakery cooperative, or a weaving cooperative, so we can weave and watch over our kids, and make money at the same time [….] I have asked the government again and again but there are no available funds.

There were some international organisations and donors, such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and CARE that recognised the specific impact of the disaster on women. 50 per cent of their efforts targeted female worker beneficiaries with considerable success. Of the 3354 workers provided with decent work by the ILO, 1536 were women (ILO 2014 ), while CARE have supported 60 women entrepreneurs to build sustainable enterprises (CARE 2015 ). However, these examples are few and far between. In Tacloban, the social arm of the Catholic Church has an ongoing training program in dressmaking for women. In Sta. Cruz, Tanauan, the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is developing a milkfish (bangus) processing facility that will be turned over to a women’s association. However, these programmes are selective and targeted, with very few beneficiaries.

We also found that the (re)creation of women focused sari-sari store entrepreneurial activity met with mixed success. Sari-sari stores are small local stalls that sell a variety of household goods. Typically, goods are sold in small units or sachets that are affordable to ‘micro consumers’ otherwise known as the ‘bottom of the pyramid market’ (Prahalad 2014 : 6). Sari-sari store schemes were promoted by a number of donors including USAID in partnership with Coca Cola and Procter and Gamble (US Embassy 2015 ). The stores were lauded (Padua 2014 ) as a means to foster entrepreneurial spirit and were highly desired as evidenced in our focus group discussions with women.

However, the sari-sari store initiatives suffered from a number of problems including oversupply. In 2016, all of the barangay officials that we interviewed reported that the number of stores had increased substantially after Yolanda, typically a figure of 30 per cent was cited. This meant that storeowners in poor communities were competing for limited customers with low spending power. We also found that beneficiaries of the sari-sari store schemes were sometimes out of their depth in their new role as ‘micro-entrepreneurs’. Whilst business training was given, including by the local government, we were also told of cases where beneficiaries could not afford to buy new stock after their start-up capital ran out or they simply spent the money they were given on household expenditure Footnote 9 and the business subsequently collapsed. It seemed that sari-sari store ownership worked best with experienced owners; those who had no experience of running a small business tended to fare less well in some cases.

In a Typhoon Yolanda response review published in April 2014, women interviewees cited sustainable livelihood as a primary need (Sanderson and Willison 2014 : 4). We repeatedly heard calls for more women’s livelihood options during our interviews and FGDs in all 3 years of our data gathering. It is vital to scale up women’s cooperative or livelihood options and extend them to other regions, especially those that are more rural and less accessible. It is also evident from the examples above that post-disaster livelihood strategies must acknowledge women’s role as caregivers and make reasonable adjustments that allow women to maximise their capabilities without compromising the care of their families.

If governmental and non-governmental agencies fail to adapt their strategies to the needs of women, or only pay lip service to gender based issues, they are discriminating against an already vulnerable group and reinforcing the social structure in ordinary times. This has a knock-on effect to the wider community as ‘the security of children and other dependents is at risk when women’s own lives are insecure’ (Enarson 2014 : 46). Even agencies that are full of good intentions may inadvertently add to the insecurity of these women if they do not take full account of their capabilities and commitments, such as their dual roles as workers and family caregivers. As mentioned in the opening paragraphs of this article age, gender, disability, sexuality, ethnic difference, locality and levels of wealth all contribute to how vulnerability and insecurity is experienced. Livelihood assistance that fails to adequately account for the practical limitations of certain groups will fail. Focus group discussions indicated that survivors with complex needs, such as women with children with disabilities, found it extremely difficult to juggle their caring responsibilities with the training and livelihood options offered by relief agencies. Sustainable livelihood strategies have to take account of complex needs, cannot be gender blind and have to be built from the bottom up.

6 Livelihood: a sustainable rebuilding?

The communities assessed in this article were still undergoing rehabilitation and rebuilding more than 6 years after Typhoon Yolanda. In the aftermath of Yolanda, INGOs and NGOs were extremely active, but by November 2016, only four to five international organisations/NGOs were still active. A lack of sustainable livelihood, inadequate and unsafe housing, the inadequate provision of utilities such as water and electricity and incomplete infrastructures such as roads and drainage in the resettlement areas continue to threaten human security. Livelihood opportunities in the resettlement sites, situated mostly away from original areas of residence and work, are generally inadequate and based on micro-entrepreneurial schemes such as food vending, sari-sari stores, and manicure and pedicure treatments. Whilst efforts were made to monitor the viability of these businesses (Roca 2017 ), intense competition, a lack of economies of scale and low profit margins has led to a bare level of subsistence. Some traditional household livelihood strategies such as the raising of pigs were banned in the resettlements, thus depriving households of a much-needed source of income. We observed schemes such as quail egg production, funded by Operation Blessing, fail over the course of our visits to the communities due to lack of demand. Consequently, people are travelling back to their original places of residence in unsafe areas to engage in their former occupations.

The withdrawal of many aid agencies left people worse off than before as the drying up of material provision and livelihood options coincided with their exit. The sheer volume of aid created by the extraordinary conditions that initially inundated Yolanda affected areas contributed to a dependence mentality in various communities. Significant free handouts, and a lack of other viable options created expectations of further assistance. Many of the interviewees we spoke to were extremely concerned as rehabilitation processes were turned over to the government, whom they considered to be the least active actor in the rehabilitation process.

Government agencies are mandated by existing national laws and frameworks and help rebuild local communities. However, work needs to be done on inter-agency and community coordination to enhance effective community rehabilitation. Agencies working in the aftermath of any disaster should concern themselves with ‘the stability and security of people’s capabilities’ (Gasper and Truong 2005 : 377). New opportunities could be offered to the survivors, capitalising on the resources and knowledge available within the region and local communities. Social and material reconstruction could come about through new, locally sensitive and more proactive ways of doing things.

Livelihood transformation programs that enable marginalized communities to reduce vulnerability through stronger social resilience should be promoted. In many of the barangays we visited, locals proposed livelihood alternatives that would actually be sustainable even when external assistance stops. We heard suggestions utilising local resources that are readily available in ordinary times, such as sand and cement factories, bakery and sewing and other forms of cooperatives. We heard calls for gender focused livelihood programs. However, the reality is that communities and individuals have little control over the creation of ‘buffers’ or the trajectory of their recovery, which are mostly initiated by external stakeholders who are only privy to the ‘extraordinary’ conditions. This entrenches them in their marginalized position in society in the pre-disaster context. They remain vulnerable and powerless and resilience remains an aspiration rather than a sustainable reality.

Thus, crucial in post-disaster livelihood recovery are DRRM plans prepared by national and local governments, together with partner agencies and communities, which anticipate possible losses and prepare for sustainable alternative livelihoods. In the three localities, we investigated there were no comprehensive local DRRM plans, which were mandated by law, before Typhoon Yolanda hit in 2013. In Tacloban, the city’s DRRM plan was only created in 2016. In Palo, there was a draft DRRM plan in existence in 2013 but it was not yet approved when Yolanda struck. Tanauan appeared to be the most advance in this respect, as the municipality was the first local government to submit a recovery roadmap or plan to the national government after Yolanda. But across all three locations plans were crafted under ‘extra-ordinary’ circumstances. Overall national and local government agency data and monitoring systems were inadequate and lacked systematic coordination with different stakeholders. This led to duplication of aid, neglect of certain areas and sectors and waste via oversupply in others.

To summarise, if livelihood is to be sustainable then it must enhance pre-disaster skills and productive assets, be scaled up and the supply of goods produced must be linked to market demand. This is why it is important that sustainable livelihoods should be crafted for ‘ordinary’ (pre-disaster) rather than ‘extraordinary’ (post-disaster) conditions. Economic booms based on the initial rehabilitation phase will inevitably collapse unless great care is taken to foster longer-term demand for goods and services and the capability to meet this demand. If local demand collapses or access to markets further afield is impractical then even initially functioning livelihood projects will be doomed to failure. For livelihood strategies to be sustainable in the long run, they must be cognizant of ‘normal’ (or ordinary) realities such as care giving duties, ease of access to the workplace, weak or corrupt governance and exposure to flooding or drought. All these should be factored in local DRRM plans that should anticipate future disasters.

7 Conclusion

Before Typhoon Yolanda, many of the population in Tacloban, Palo and Tanauan living in low-lying coastal areas were vulnerable to inundation during typhoons (Lagmay et al. 2015 ). In some locations, this is still the case. Many residents in impoverished coastal barangays lived on the shore, or even over, the water with houses supported by wooden or bamboo stilts. The communities were chronically vulnerable to the elements. The capacity to build buffers against shocks or stresses to livelihood or to diversify activity was somewhat limited in these communities. People did not have the freedom to move away from the sea as land was scarce and livelihood opportunities were tied to proximity to the sea and other nearby means of making a living. Meanwhile, attempts at diversification were sometimes hindered by the inexperience of ‘micro-entrepreneurs’, intense competition over limited local markets and the piecemeal relocation of communities to higher ground.

There needs to be a carefully managed transition between emergency cash for work or cash for no work programs and diverse and sustainable livelihood building. Cosmetic post-disaster relief strategies that result in similar or equal but different vulnerabilities do not result in resilience. Similarly, the restoration of a pre-disaster status quo does not equate to resilience if suboptimal pre-disaster socio-economic structures remain entrenched. People and communities remain vulnerable under such conditions as they cannot effectively mitigate the risks that they face. This vulnerability is experienced unevenly. Certain livelihood sectors such as fishermen, farmers and own account workers; and certain demographics, such as women and the elderly, were particularly vulnerable.

The overarching objective of this article has been to critically assess the livelihood strategies that were used to reduce individuals’ and communities’ vulnerability in the aftermath of Yolanda. It appears that despite the significant relief and rehabilitation effort in the aftermath of the Typhoon Yolanda, individuals and communities in the areas we studied remain vulnerable. They are functioning, and people often see themselves as resilient. However, they still face a range of obstacles that impede the building of buffers against future shocks and stresses as most strategies are tailored in, and towards, ‘extraordinary’ conditions. Post-disaster livelihood assistance often failed to account for actual need, the sustainability of projects, pre-existing skills sets or caregiving responsibilities. Complex vulnerabilities experienced by women, the elderly, and those tasked with caring for people with disabilities were often overlooked. Coordination mechanisms and legal frameworks that should have anticipated these considerations were often either ignored or weakly implemented. The local governments that were supposed to be at the frontline of DRRM work were unprepared, overwhelmed, and caught off-guard by Yolanda and its aftermath. It also appears that participatory mechanisms where substantial community inputs are considered, especially in livelihood plans, were lacking.

Overall resilience must be about bouncing ‘forward’ rather than bouncing ‘back’ to an improved socio-economic normalcy, especially for the most vulnerable in society. For livelihood to be sustainable, we need to address pre-disaster social vulnerability entrenched by multiple factors such as gender and other protected characteristics. Post-disaster resilience can be meaningfully related to sustainable livelihood but bringing about change that builds capacity and alleviates vulnerability is key. Across cases this could include a realistic examination of local environmental factors and natural resource dependence, culture and the role of women, infrastructure and market access for locally produced goods and services and the extent to which livelihood can be organised on a collective basis. Government agencies and non-governmental organisations should also consider further the diverse earning streams of the poor that can be adjusted to account for factors such as caregiving, seasonal changes in the weather or market demand in holiday or celebration periods. We observed strategies that neglected empowerment, capacity building and the importance of giving voice to individuals and their communities, especially the most vulnerable ones. If agency is to be effectively built, survivors should be helped to identify for themselves the livelihood strategies that reduce vulnerability and help build secure futures.

Finally, in the future DRRM strategies need to mainstream sustainable livelihood into development planning in ways that boost capabilities and reduce vulnerability. A systematic mapping of vulnerability, even before disaster strikes, with the participation of local people and communities, could help aid agencies and governments identify policy shortcomings and become more reflective about what disaster relief could and should achieve, particularly in building sustainable livelihoods.

In the aftermath of disasters, asset bubbles can be created whereby the cost of goods and services are rapidly inflated due to demand generated by aid influx. Such assets could include e.g. catering and accommodation, office space, interpreters, drivers and labourers, construction materials and machinery or water. Where local economies rely on sectors significantly affected by the disaster such as tourism, farming or fisheries, and piecemeal own account working is common dependence on the disaster economy is likely to be higher. This means that when demand contracts and asset prices fall, or the bubble bursts, the local economy could end up worse off than before the disaster.