Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and Templates

A rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations.

Rubrics can help instructors communicate expectations to students and assess student work fairly, consistently and efficiently. Rubrics can provide students with informative feedback on their strengths and weaknesses so that they can reflect on their performance and work on areas that need improvement.

How to Get Started

Best practices, moodle how-to guides.

- Workshop Recording (Fall 2022)

- Workshop Registration

Step 1: Analyze the assignment

The first step in the rubric creation process is to analyze the assignment or assessment for which you are creating a rubric. To do this, consider the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the assignment and your feedback? What do you want students to demonstrate through the completion of this assignment (i.e. what are the learning objectives measured by it)? Is it a summative assessment, or will students use the feedback to create an improved product?

- Does the assignment break down into different or smaller tasks? Are these tasks equally important as the main assignment?

- What would an “excellent” assignment look like? An “acceptable” assignment? One that still needs major work?

- How detailed do you want the feedback you give students to be? Do you want/need to give them a grade?

Step 2: Decide what kind of rubric you will use

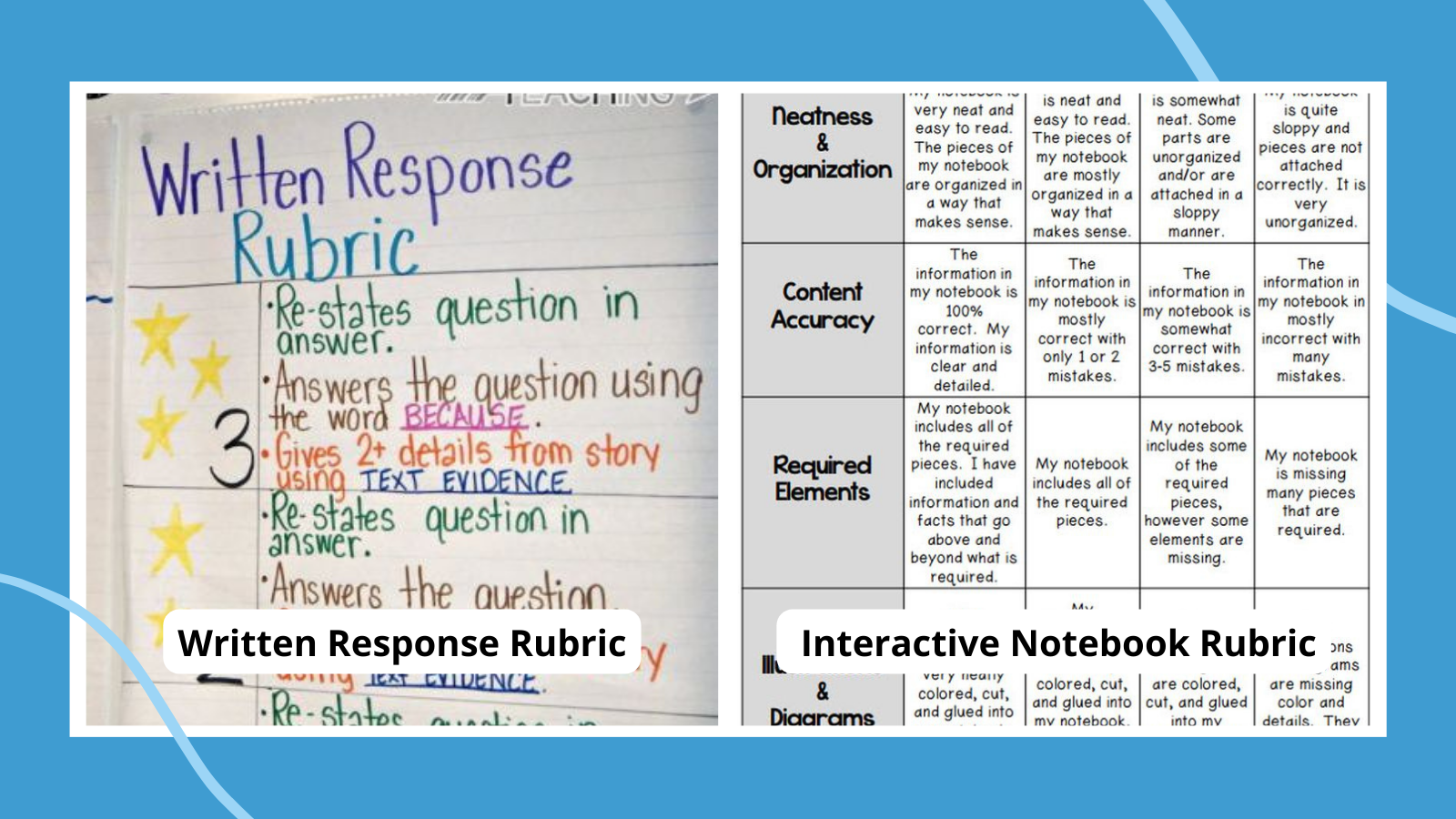

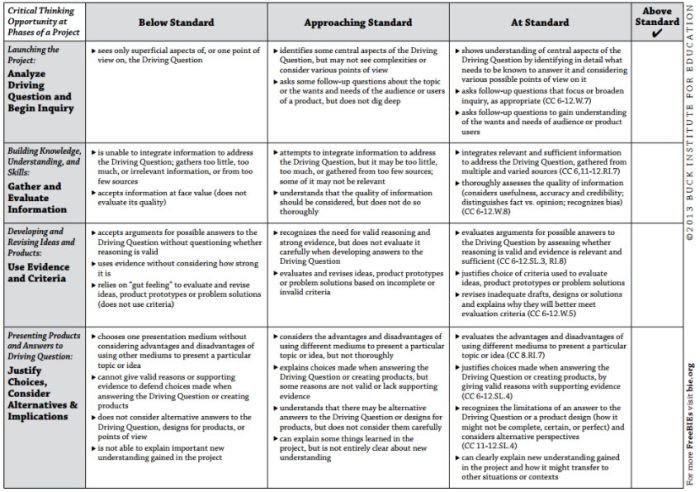

Types of rubrics: holistic, analytic/descriptive, single-point

Holistic Rubric. A holistic rubric includes all the criteria (such as clarity, organization, mechanics, etc.) to be considered together and included in a single evaluation. With a holistic rubric, the rater or grader assigns a single score based on an overall judgment of the student’s work, using descriptions of each performance level to assign the score.

Advantages of holistic rubrics:

- Can p lace an emphasis on what learners can demonstrate rather than what they cannot

- Save grader time by minimizing the number of evaluations to be made for each student

- Can be used consistently across raters, provided they have all been trained

Disadvantages of holistic rubrics:

- Provide less specific feedback than analytic/descriptive rubrics

- Can be difficult to choose a score when a student’s work is at varying levels across the criteria

- Any weighting of c riteria cannot be indicated in the rubric

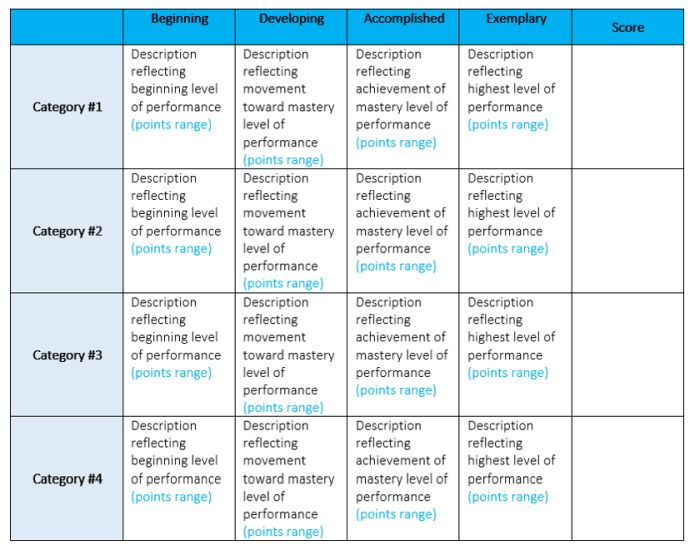

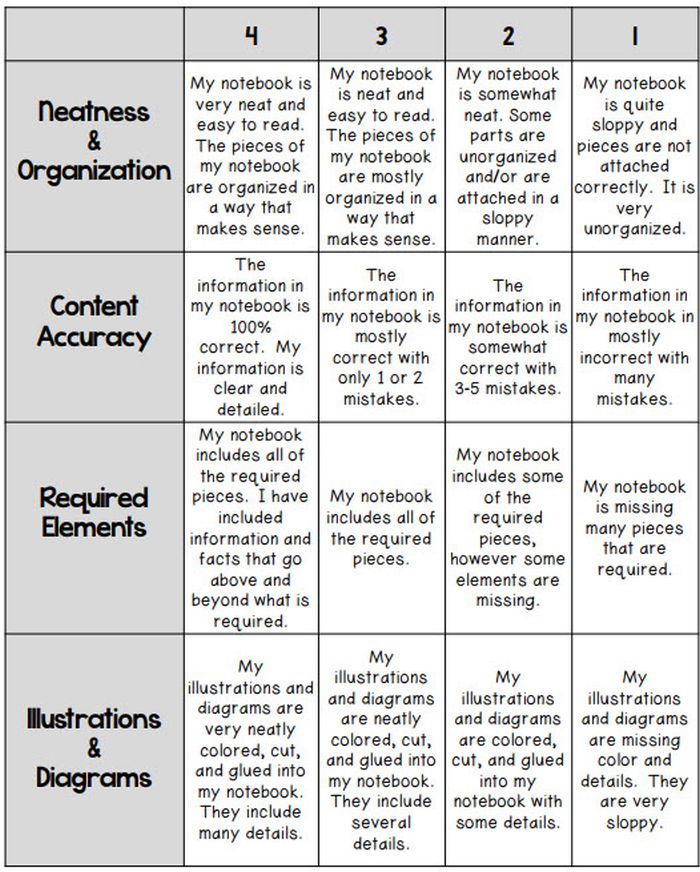

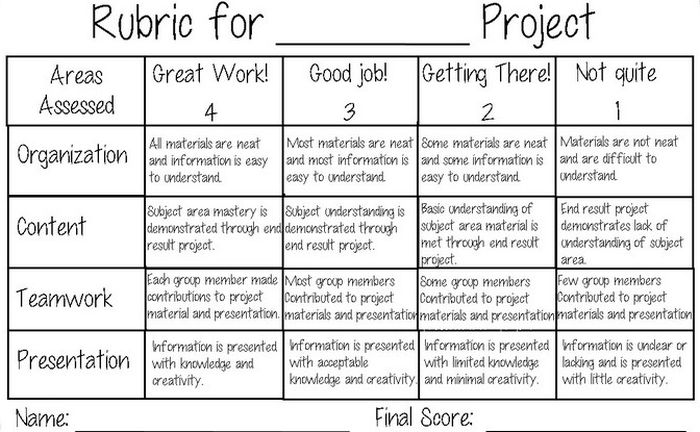

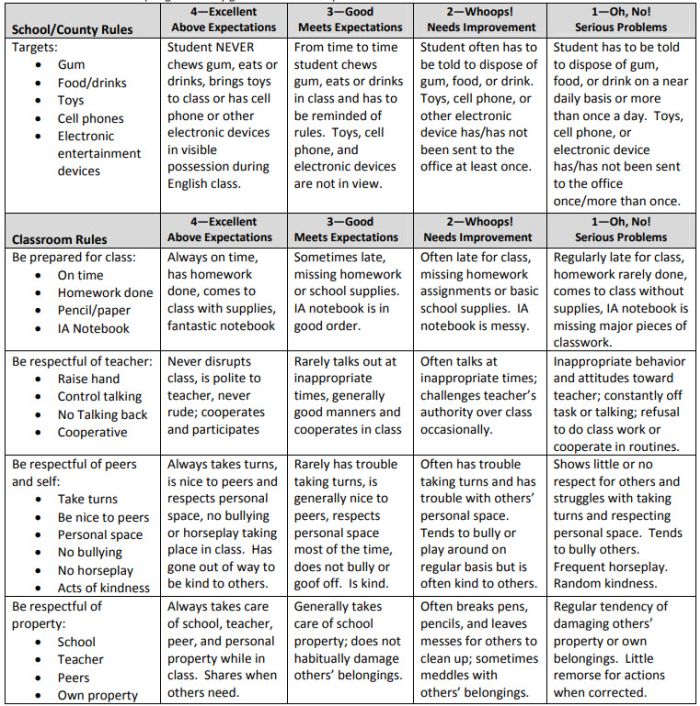

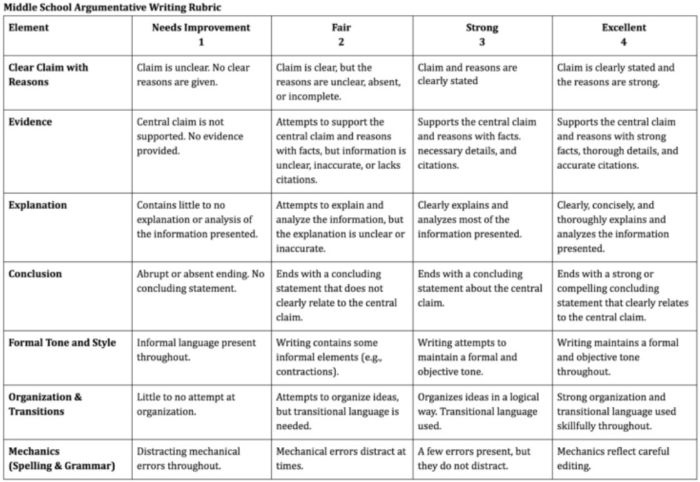

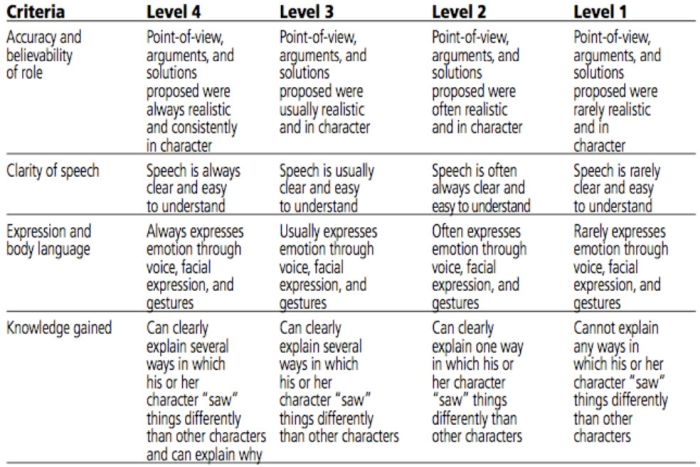

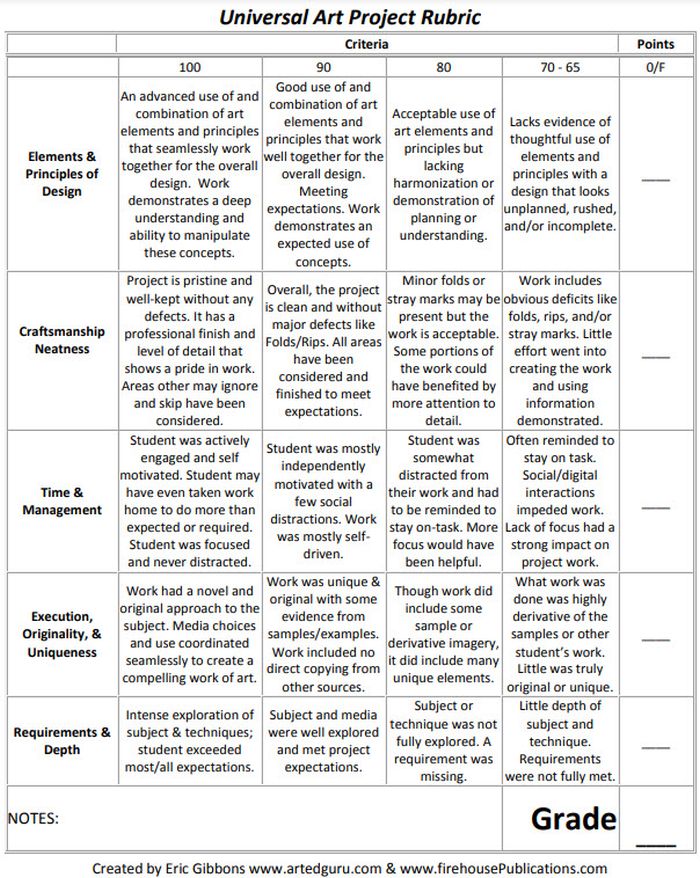

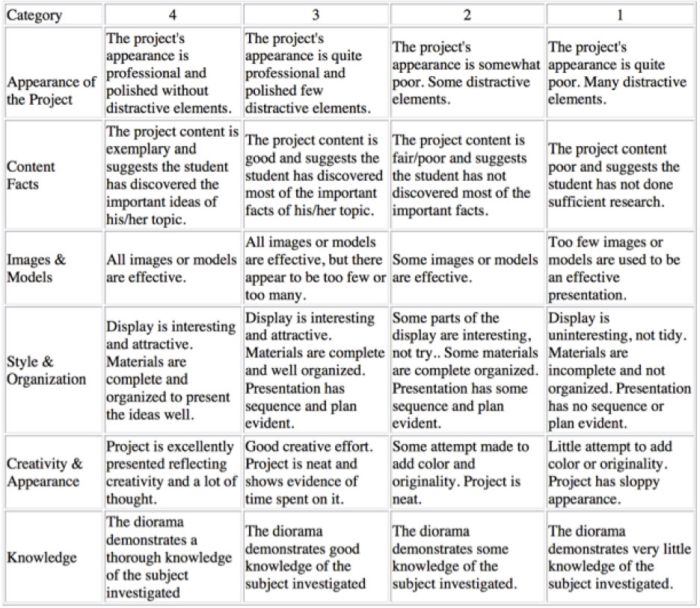

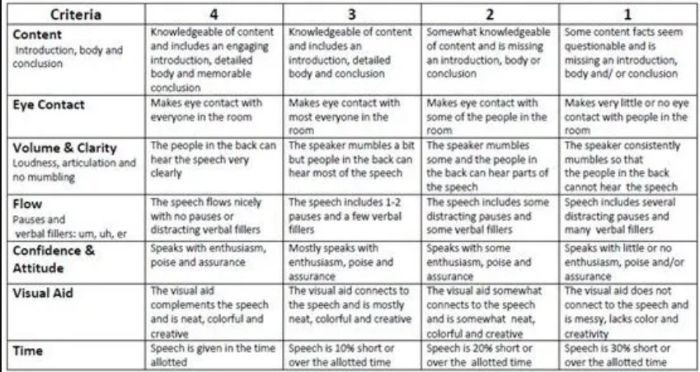

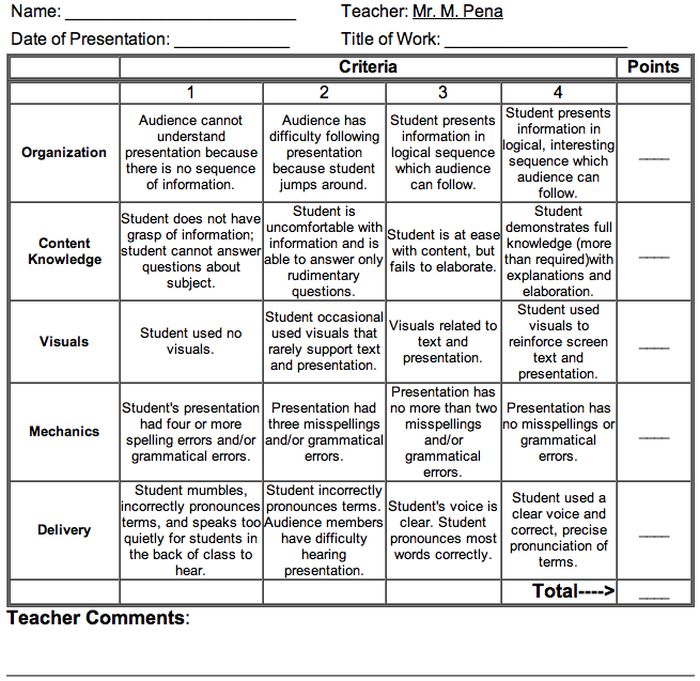

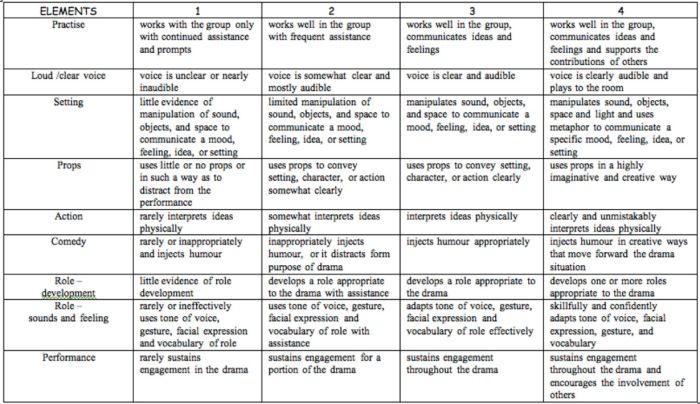

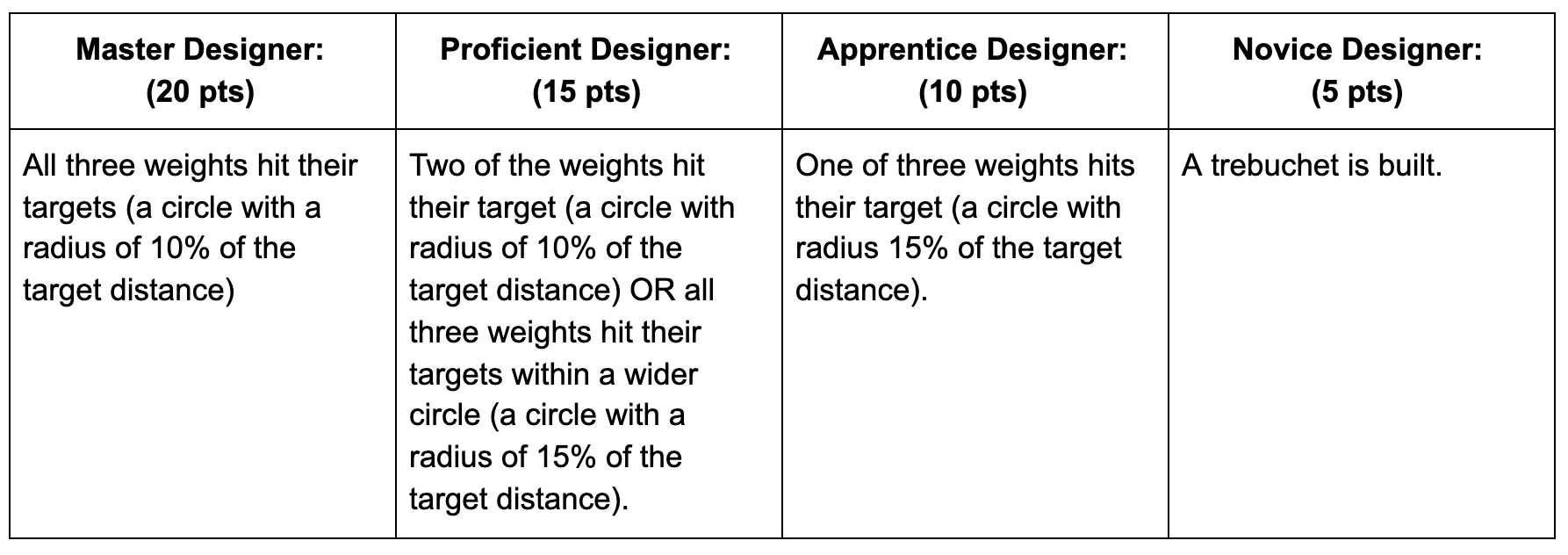

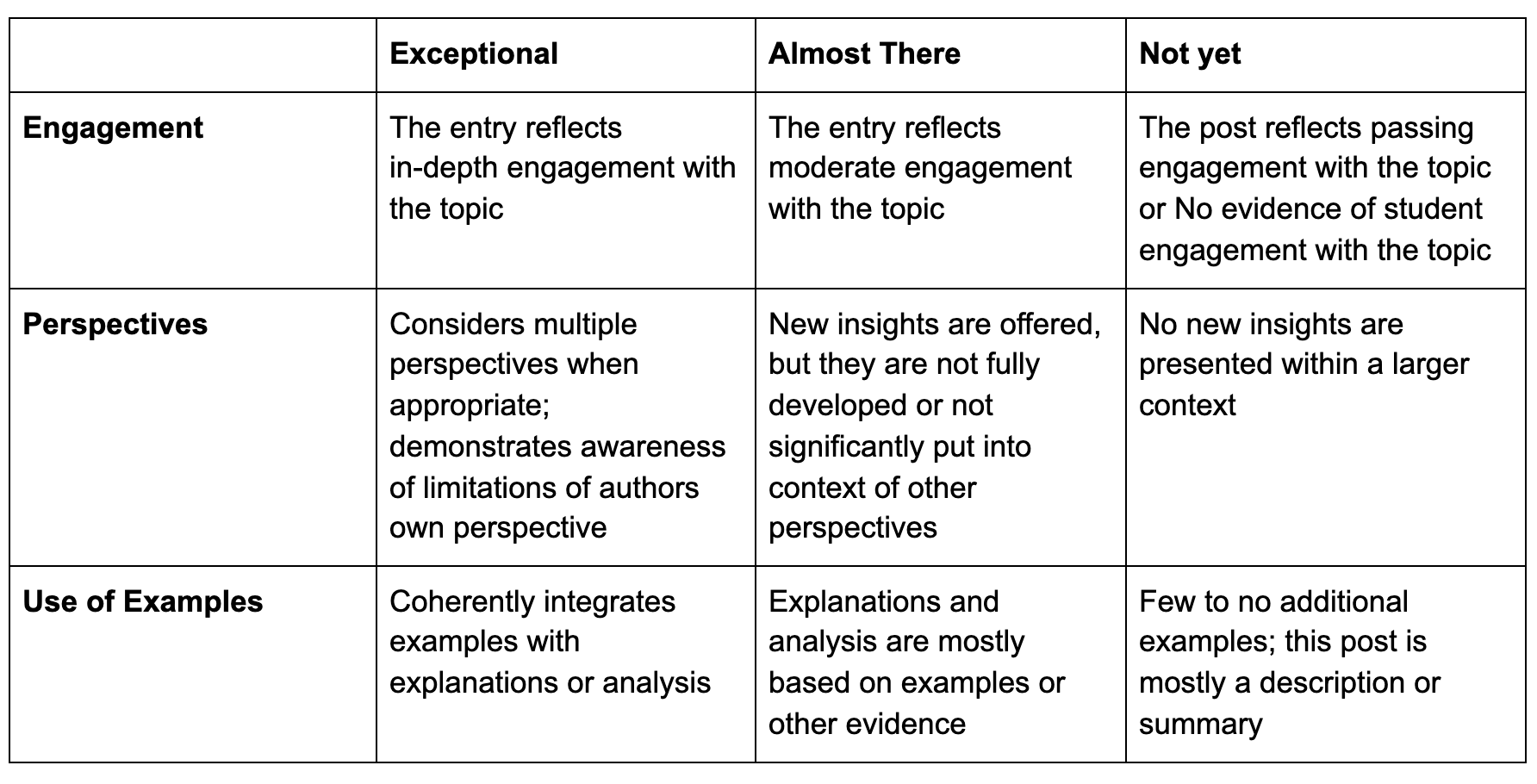

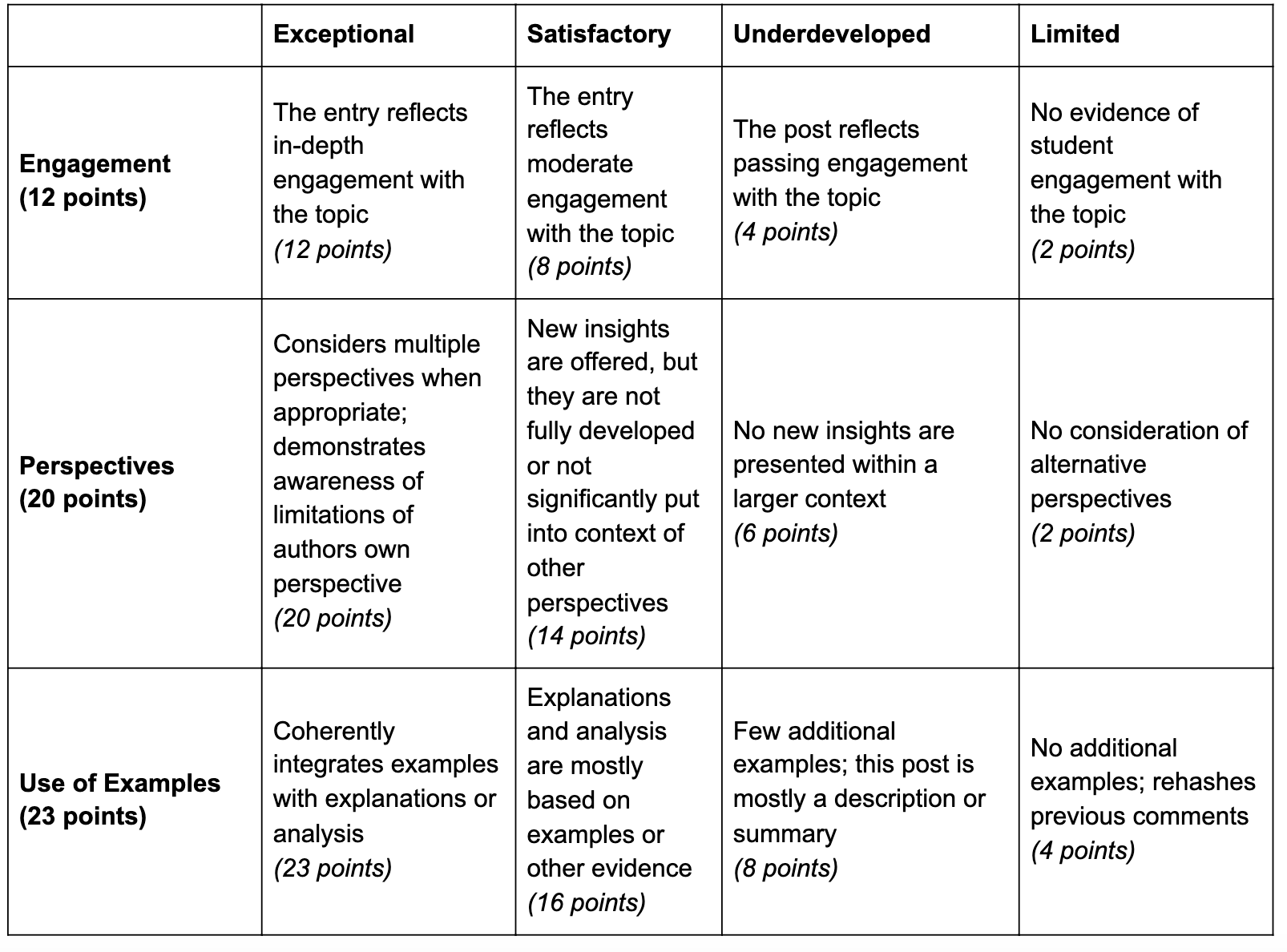

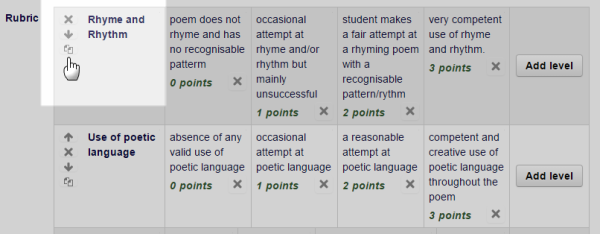

Analytic/Descriptive Rubric . An analytic or descriptive rubric often takes the form of a table with the criteria listed in the left column and with levels of performance listed across the top row. Each cell contains a description of what the specified criterion looks like at a given level of performance. Each of the criteria is scored individually.

Advantages of analytic rubrics:

- Provide detailed feedback on areas of strength or weakness

- Each criterion can be weighted to reflect its relative importance

Disadvantages of analytic rubrics:

- More time-consuming to create and use than a holistic rubric

- May not be used consistently across raters unless the cells are well defined

- May result in giving less personalized feedback

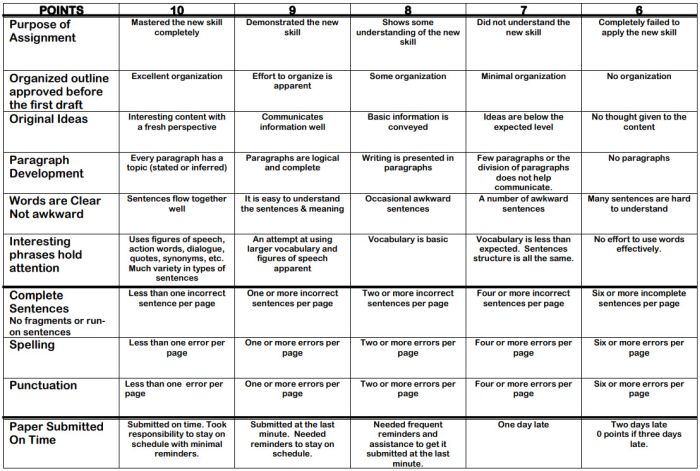

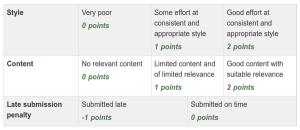

Single-Point Rubric . A single-point rubric is breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria, but instead of describing different levels of performance, only the “proficient” level is described. Feedback space is provided for instructors to give individualized comments to help students improve and/or show where they excelled beyond the proficiency descriptors.

Advantages of single-point rubrics:

- Easier to create than an analytic/descriptive rubric

- Perhaps more likely that students will read the descriptors

- Areas of concern and excellence are open-ended

- May removes a focus on the grade/points

- May increase student creativity in project-based assignments

Disadvantage of analytic rubrics: Requires more work for instructors writing feedback

Step 3 (Optional): Look for templates and examples.

You might Google, “Rubric for persuasive essay at the college level” and see if there are any publicly available examples to start from. Ask your colleagues if they have used a rubric for a similar assignment. Some examples are also available at the end of this article. These rubrics can be a great starting point for you, but consider steps 3, 4, and 5 below to ensure that the rubric matches your assignment description, learning objectives and expectations.

Step 4: Define the assignment criteria

Make a list of the knowledge and skills are you measuring with the assignment/assessment Refer to your stated learning objectives, the assignment instructions, past examples of student work, etc. for help.

Helpful strategies for defining grading criteria:

- Collaborate with co-instructors, teaching assistants, and other colleagues

- Brainstorm and discuss with students

- Can they be observed and measured?

- Are they important and essential?

- Are they distinct from other criteria?

- Are they phrased in precise, unambiguous language?

- Revise the criteria as needed

- Consider whether some are more important than others, and how you will weight them.

Step 5: Design the rating scale

Most ratings scales include between 3 and 5 levels. Consider the following questions when designing your rating scale:

- Given what students are able to demonstrate in this assignment/assessment, what are the possible levels of achievement?

- How many levels would you like to include (more levels means more detailed descriptions)

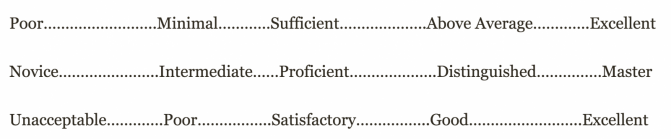

- Will you use numbers and/or descriptive labels for each level of performance? (for example 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 and/or Exceeds expectations, Accomplished, Proficient, Developing, Beginning, etc.)

- Don’t use too many columns, and recognize that some criteria can have more columns that others . The rubric needs to be comprehensible and organized. Pick the right amount of columns so that the criteria flow logically and naturally across levels.

Step 6: Write descriptions for each level of the rating scale

Artificial Intelligence tools like Chat GPT have proven to be useful tools for creating a rubric. You will want to engineer your prompt that you provide the AI assistant to ensure you get what you want. For example, you might provide the assignment description, the criteria you feel are important, and the number of levels of performance you want in your prompt. Use the results as a starting point, and adjust the descriptions as needed.

Building a rubric from scratch

For a single-point rubric , describe what would be considered “proficient,” i.e. B-level work, and provide that description. You might also include suggestions for students outside of the actual rubric about how they might surpass proficient-level work.

For analytic and holistic rubrics , c reate statements of expected performance at each level of the rubric.

- Consider what descriptor is appropriate for each criteria, e.g., presence vs absence, complete vs incomplete, many vs none, major vs minor, consistent vs inconsistent, always vs never. If you have an indicator described in one level, it will need to be described in each level.

- You might start with the top/exemplary level. What does it look like when a student has achieved excellence for each/every criterion? Then, look at the “bottom” level. What does it look like when a student has not achieved the learning goals in any way? Then, complete the in-between levels.

- For an analytic rubric , do this for each particular criterion of the rubric so that every cell in the table is filled. These descriptions help students understand your expectations and their performance in regard to those expectations.

Well-written descriptions:

- Describe observable and measurable behavior

- Use parallel language across the scale

- Indicate the degree to which the standards are met

Step 7: Create your rubric

Create your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle. Rubric creators: Rubistar , iRubric

Step 8: Pilot-test your rubric

Prior to implementing your rubric on a live course, obtain feedback from:

- Teacher assistants

Try out your new rubric on a sample of student work. After you pilot-test your rubric, analyze the results to consider its effectiveness and revise accordingly.

- Limit the rubric to a single page for reading and grading ease

- Use parallel language . Use similar language and syntax/wording from column to column. Make sure that the rubric can be easily read from left to right or vice versa.

- Use student-friendly language . Make sure the language is learning-level appropriate. If you use academic language or concepts, you will need to teach those concepts.

- Share and discuss the rubric with your students . Students should understand that the rubric is there to help them learn, reflect, and self-assess. If students use a rubric, they will understand the expectations and their relevance to learning.

- Consider scalability and reusability of rubrics. Create rubric templates that you can alter as needed for multiple assignments.

- Maximize the descriptiveness of your language. Avoid words like “good” and “excellent.” For example, instead of saying, “uses excellent sources,” you might describe what makes a resource excellent so that students will know. You might also consider reducing the reliance on quantity, such as a number of allowable misspelled words. Focus instead, for example, on how distracting any spelling errors are.

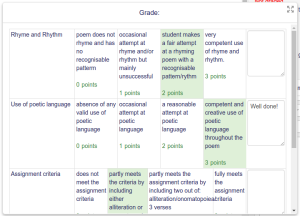

Example of an analytic rubric for a final paper

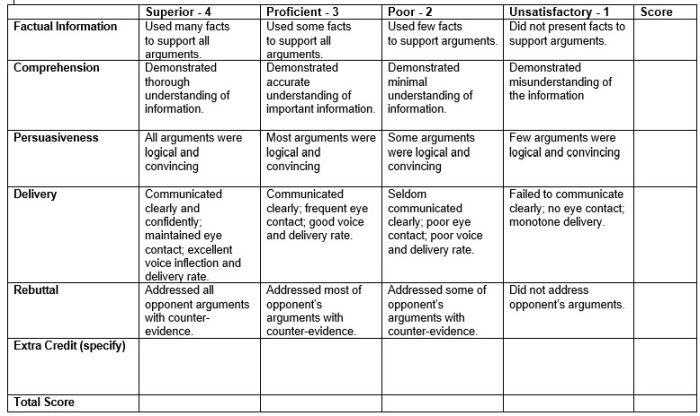

Example of a holistic rubric for a final paper, single-point rubric, more examples:.

- Single Point Rubric Template ( variation )

- Analytic Rubric Template make a copy to edit

- A Rubric for Rubrics

- Bank of Online Discussion Rubrics in different formats

- Mathematical Presentations Descriptive Rubric

- Math Proof Assessment Rubric

- Kansas State Sample Rubrics

- Design Single Point Rubric

Technology Tools: Rubrics in Moodle

- Moodle Docs: Rubrics

- Moodle Docs: Grading Guide (use for single-point rubrics)

Tools with rubrics (other than Moodle)

- Google Assignments

- Turnitin Assignments: Rubric or Grading Form

Other resources

- DePaul University (n.d.). Rubrics .

- Gonzalez, J. (2014). Know your terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics . Cult of Pedagogy.

- Goodrich, H. (1996). Understanding rubrics . Teaching for Authentic Student Performance, 54 (4), 14-17. Retrieved from

- Miller, A. (2012). Tame the beast: tips for designing and using rubrics.

- Ragupathi, K., Lee, A. (2020). Beyond Fairness and Consistency in Grading: The Role of Rubrics in Higher Education. In: Sanger, C., Gleason, N. (eds) Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Assessment Rubrics

A rubric is commonly defined as a tool that articulates the expectations for an assignment by listing criteria, and for each criteria, describing levels of quality (Andrade, 2000; Arter & Chappuis, 2007; Stiggins, 2001). Criteria are used in determining the level at which student work meets expectations. Markers of quality give students a clear idea about what must be done to demonstrate a certain level of mastery, understanding, or proficiency (i.e., "Exceeds Expectations" does xyz, "Meets Expectations" does only xy or yz, "Developing" does only x or y or z). Rubrics can be used for any assignment in a course, or for any way in which students are asked to demonstrate what they've learned. They can also be used to facilitate self and peer-reviews of student work.

Rubrics aren't just for summative evaluation. They can be used as a teaching tool as well. When used as part of a formative assessment, they can help students understand both the holistic nature and/or specific analytics of learning expected, the level of learning expected, and then make decisions about their current level of learning to inform revision and improvement (Reddy & Andrade, 2010).

Why use rubrics?

Rubrics help instructors:

Provide students with feedback that is clear, directed and focused on ways to improve learning.

Demystify assignment expectations so students can focus on the work instead of guessing "what the instructor wants."

Reduce time spent on grading and develop consistency in how you evaluate student learning across students and throughout a class.

Rubrics help students:

Focus their efforts on completing assignments in line with clearly set expectations.

Self and Peer-reflect on their learning, making informed changes to achieve the desired learning level.

Developing a Rubric

During the process of developing a rubric, instructors might:

Select an assignment for your course - ideally one you identify as time intensive to grade, or students report as having unclear expectations.

Decide what you want students to demonstrate about their learning through that assignment. These are your criteria.

Identify the markers of quality on which you feel comfortable evaluating students’ level of learning - often along with a numerical scale (i.e., "Accomplished," "Emerging," "Beginning" for a developmental approach).

Give students the rubric ahead of time. Advise them to use it in guiding their completion of the assignment.

It can be overwhelming to create a rubric for every assignment in a class at once, so start by creating one rubric for one assignment. See how it goes and develop more from there! Also, do not reinvent the wheel. Rubric templates and examples exist all over the Internet, or consider asking colleagues if they have developed rubrics for similar assignments.

Sample Rubrics

Examples of holistic and analytic rubrics : see Tables 2 & 3 in “Rubrics: Tools for Making Learning Goals and Evaluation Criteria Explicit for Both Teachers and Learners” (Allen & Tanner, 2006)

Examples across assessment types : see “Creating and Using Rubrics,” Carnegie Mellon Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and & Educational Innovation

“VALUE Rubrics” : see the Association of American Colleges and Universities set of free, downloadable rubrics, with foci including creative thinking, problem solving, and information literacy.

Andrade, H. 2000. Using rubrics to promote thinking and learning. Educational Leadership 57, no. 5: 13–18. Arter, J., and J. Chappuis. 2007. Creating and recognizing quality rubrics. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall. Stiggins, R.J. 2001. Student-involved classroom assessment. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448.

Center for Teaching Innovation

Resource library.

- AACU VALUE Rubrics

Using rubrics

A rubric is a type of scoring guide that assesses and articulates specific components and expectations for an assignment. Rubrics can be used for a variety of assignments: research papers, group projects, portfolios, and presentations.

Why use rubrics?

Rubrics help instructors:

- Assess assignments consistently from student-to-student.

- Save time in grading, both short-term and long-term.

- Give timely, effective feedback and promote student learning in a sustainable way.

- Clarify expectations and components of an assignment for both students and course teaching assistants (TAs).

- Refine teaching methods by evaluating rubric results.

Rubrics help students:

- Understand expectations and components of an assignment.

- Become more aware of their learning process and progress.

- Improve work through timely and detailed feedback.

Considerations for using rubrics

When developing rubrics consider the following:

- Although it takes time to build a rubric, time will be saved in the long run as grading and providing feedback on student work will become more streamlined.

- A rubric can be a fillable pdf that can easily be emailed to students.

- They can be used for oral presentations.

- They are a great tool to evaluate teamwork and individual contribution to group tasks.

- Rubrics facilitate peer-review by setting evaluation standards. Have students use the rubric to provide peer assessment on various drafts.

- Students can use them for self-assessment to improve personal performance and learning. Encourage students to use the rubrics to assess their own work.

- Motivate students to improve their work by using rubric feedback to resubmit their work incorporating the feedback.

Getting Started with Rubrics

- Start small by creating one rubric for one assignment in a semester.

- Ask colleagues if they have developed rubrics for similar assignments or adapt rubrics that are available online. For example, the AACU has rubrics for topics such as written and oral communication, critical thinking, and creative thinking. RubiStar helps you to develop your rubric based on templates.

- Examine an assignment for your course. Outline the elements or critical attributes to be evaluated (these attributes must be objectively measurable).

- Create an evaluative range for performance quality under each element; for instance, “excellent,” “good,” “unsatisfactory.”

- Avoid using subjective or vague criteria such as “interesting” or “creative.” Instead, outline objective indicators that would fall under these categories.

- The criteria must clearly differentiate one performance level from another.

- Assign a numerical scale to each level.

- Give a draft of the rubric to your colleagues and/or TAs for feedback.

- Train students to use your rubric and solicit feedback. This will help you judge whether the rubric is clear to them and will identify any weaknesses.

- Rework the rubric based on the feedback.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

IUPUI IUPUI IUPUI

- Center Directory

- Hours, Location, & Contact Info

- Plater-Moore Conference on Teaching and Learning

- Teaching Foundations Webinar Series

- Associate Faculty Development

- Early Career Teaching Academy

- Faculty Fellows Program

- Graduate Student and Postdoc Teaching Development

- Awardees' Expectations

- Request for Proposals

- Proposal Writing Guidelines

- Support Letter

- Proposal Review Process and Criteria

- Support for Developing a Proposal

- Download the Budget Worksheet

- CEG Travel Grant

- Albright and Stewart

- Bayliss and Fuchs

- Glassburn and Starnino

- Rush Hovde and Stella

- Mithun and Sankaranarayanan

- Hollender, Berlin, and Weaver

- Rose and Sorge

- Dawkins, Morrow, Cooper, Wilcox, and Rebman

- Wilkerson and Funk

- Vaughan and Pierce

- CEG Scholars

- Broxton Bird

- Jessica Byram

- Angela and Neetha

- Travis and Mathew

- Kelly, Ron, and Jill

- Allison, David, Angela, Priya, and Kelton

- Pamela And Laura

- Tanner, Sally, and Jian Ye

- Mythily and Twyla

- Learning Environments Grant

- Extended Reality Initiative(XRI)

- Champion for Teaching Excellence Award

- Feedback on Teaching

- Consultations

- Equipment Loans

- Quality Matters@IU

- To Your Door Workshops

- Support for DEI in Teaching

- IU Teaching Resources

- Just-In-Time Course Design

- Teaching Online

- Scholarly Teaching Taxonomy

- The Forum Network

- Media Production Spaces

- CTL Happenings Archive

- Recommended Readings Archive

Center for Teaching and Learning

- Assessing Student Learning

Creating and Using Rubrics

Rubrics are both assessment tools for faculty and learning tools for students that can ease anxiety about the grading process for both parties. Rubrics lay out specific criteria and performance expectations for an assignment. They help students and instructors stay focused on those expectations and to be more confident in their work as a result. Creating rubrics does require a substantial time investment up front, but this process will result in reduced time spent grading or explaining assignment criteria down the road.

Reasons for Using Rubrics

Research indicates that rubrics:

- Rubrics can help normalize the work of multiple graders, e.g., across different sections of a single course or in large lecture courses where TAs manage labs or discussion groups.

- Well-crafted rubrics can reduce the time that faculty spend grading assignments.

- Timely feedback has a positive impact on the learning process.

- When coupled with other forms of feedback (e.g., brief, individualized comments) rubrics show students how to improve.

- By giving students a clear sense of what constitutes different levels of performance, rubrics can make self- and peer-assessments more meaningful and effective.

- If students complete an assignment with a rubric as a guide, then students are better equipped to think critically about their work and to improve it.

- Rubrics establish, in great detail, what different levels of student work look like. If students have seen an assignment rubric in advance and know that they will be held accountable to it, defending grade decisions can be much easier.

Tips for Creating Effective Rubrics

- To create performance descriptions for a new rubric, first rank student responses to an assignment from best to mediocre to worst. Read back through the assignments in that order. Record the characteristics that define student work at each of the three levels. Use your notes to craft the performance descriptions for each criteria category of your new rubric.

- Alternately, start by drafting your high and low performance descriptions for each criteria category, then fill in the mid-range descriptions.

- Use the language of your assignment prompt in your rubric.

- Consider rubric language carefully—how do you encapsulate the range of student responses that could realistically fall in a given cell? Lots of “and/or” statements.

- E.g., “Introduction and/or conclusion handled well but may leave some points unaddressed;” “Sources may be improperly cited or may be missing”

- Completely Effective, Reasonably Effective, Ineffective

- Superb, Strong, Acceptable, Weak

- Compelling, Reasonable, Basic

- Advanced, Intermediate, Novice

- Proficient, Not Yet Proficient, Beginning

- Outstanding, Very Good, Good, Basic, Unsatisfactory

- Exemplary, Proficient, Competent, Developing, Beginning

Tips for Testing and Revising Rubrics

- Score sample assignments without a rubric and then with one. Compare the results. Ask a colleague to use your rubric to do the same.

- Ask a colleague to use your rubric to score student work you've already scored with the rubric and then compare results.

- Get your colleagues' feedback on the alignment of your rubric's grading criteria with your assignment and course-level learning objectives.

- Discuss your rubrics with your students and determine what they do and do not like or understand about them.

Tips for Using Rubrics

- Create a generic rubric template that you can modify for specific assignments.

- Keep the rubric to one page if at all possible. Give the rubric a descriptive title that clearly links it to the assignment prompt and/or digital grade book.

- Give the rubric to students in advance (i.e., with the related assignment prompt) and discuss it with them. Explain the purpose of the rubric, and require students to use the rubric for self-assessment and to reflect on process.

- Allow students to score example work with the rubric before attempting actual peer- or self-review. Discuss with the students how the example work correlates to the competency levels on the rubric.

- Consider engaging in active-learning, rubric development exercises with your students. Have your students help you identify relevant assignment components or develop drafts of your performance descriptions, etc.

- When returning work to students, only highlight those portions of the rubric text that are relevant.

- Couple rubrics with other measures or forms of feedback. Giving brief additional feedback that responds holistically and/or subjectively to student work is a good way to support formative assessment.

- Include relevant learning objectives on your rubrics and/or related assignment prompts.

- To document trends in your teaching, keep copies of rubrics that you return to students and review them later on. Analyzing groups of graded rubrics over time can give you a sense of what might be weak in your teaching and what you need to focus on in the future.

- Canvas has a built-in rubric tool .

- iRubric can be used create be used to create rubrics in Canvas as well (availability varies by department).

Online Resources

- Rubrics resource page from the Eberly Center at Carnegie Mellon University (includes several discipline-specific examples):

- Sample Rubrics from the Association for the Assessment of Learning in Higher Education

- Association of American Colleges and Universities VALUE (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education) Rubrics

- Holistic Essay-Grading Rubrics at the University of Georgia, Athens

- Quality Matters Rubric for Assessing University-Level Online and Blended Courses (Seventh Edition)

- iRubric Tool and Samples

- Canvas Guides on Rubrics:

- Creating a rubric

- Editing a rubric

- Managing course rubrics

- Rubrics in Speedgrader

Barkley, E.F., Cross, P.K., and Major, C.H. (2005). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Barney, Sebastian, et al . “Improving Students with Rubric-Based Self-Assessment and Oral Feedback.” IEEE Transaction on Education 55, no. 3 (August 2012): 319-25.

Besterfield-Sacre, Mary, et al . “Scoring Concept Maps: An Integrated Rubric for Assessing Engineering Education.” Journal of Engineering Education 93, no. 2 (2004): 105-15.

Broad, Brian. What we Really Value: Beyond Rubrics in Teaching and Writing Assessment . Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2003.

Hout, Brian. Rearticulating Writing Assessment for Teaching and Learning . Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2002.

Howell, Rebecca J. “Exploring the Impact of Grading Rubrics on Academic Performance: Findings from a Quasi-Experimental, Pre-Post Evaluation.” Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 22, no. 2 (2011): 31-49.

Jonsson, Anders and Gunilla Svingby. “The Use of Scoring Rubrics: Reliability, Validity, and Educational Consequences.” Educational Research Review 2 (2007): 130-44.

Kishbaugh, Tara L.S., et al . “Measuring Beyond Content: A Rubric Bank for Assessing Skills in Authentic Research Assignments in the Sciences.” Chemistry Education Research and Practice 13 (2012): 268-76.

Leist, Cathy, et al . “The Effects of Using a Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric to Assess Undergraduate Students’ Reading Skills.” Journal of College Reading and Learning 43, no. 1 (Fall 2012): 31-58.

Livingston, Michael and Lisa Storm Fink. “The Infamy of Grading Rubrics.” English Journal, High School Edition 102, no. 2 (Nov. 2012): 108-13.

Stevens, Dannelle D. and Antonia J. Levi. Introduction to Rubrics: An Assessment Tool to Save GradingTime, Convey Effective Feedback and Promote Student Learning . (Sterling, VA: Stylus Press, 2005).

Wilson, Maja. Rethinking Rubrics in Writing Assessment . (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2006).

Authored by James Gregory (September, 2014)

Updated by James Gregory (September, 2015)

Updated by James Gregory (February, 2016)

Updated by Andi Rehak (February, 2017)

Center for Teaching and Learning resources and social media channels

Skip to Content

Other ways to search:

- Events Calendar

Rubrics are a set of criteria to evaluate performance on an assignment or assessment. Rubrics can communicate expectations regarding the quality of work to students and provide a standardized framework for instructors to assess work. Rubrics can be used for both formative and summative assessment. They are also crucial in encouraging self-assessment of work and structuring peer-assessments.

Why use rubrics?

Rubrics are an important tool to assess learning in an equitable and just manner. This is because they enable:

- A common set of standards and criteria to be uniformly applied, which can mitigate bias

- Transparency regarding the standards and criteria on which students are evaluated

- Efficient grading with timely and actionable feedback

- Identifying areas in which students need additional support and guidance

- The use of objective, criterion-referenced metrics for evaluation

Some instructors may be reluctant to provide a rubric to grade assessments under the perception that it stifles student creativity (Haugnes & Russell, 2018). However, sharing the purpose of an assessment and criteria for success in the form of a rubric along with relevant examples has been shown to particularly improve the success of BIPOC, multiracial, and first-generation students (Jonsson, 2014; Winkelmes, 2016). Improved success in assessments is generally associated with an increased sense of belonging which, in turn, leads to higher student retention and more equitable outcomes in the classroom (Calkins & Winkelmes, 2018; Weisz et al., 2023). By not providing a rubric, faculty may risk having students guess the criteria on which they will be evaluated. When students have to guess what expectations are, it may unfairly disadvantage students who are first-generation, BIPOC, international, or otherwise have not been exposed to the cultural norms that have dominated higher-ed institutions in the U.S (Shapiro et al., 2023). Moreover, in such cases, criteria may be applied inconsistently for students leading to biases in grades awarded to students.

Steps for Creating a Rubric

Clearly state the purpose of the assessment, which topic(s) learners are being tested on, the type of assessment (e.g., a presentation, essay, group project), the skills they are being tested on (e.g., writing, comprehension, presentation, collaboration), and the goal of the assessment for instructors (e.g., gauging formative or summative understanding of the topic).

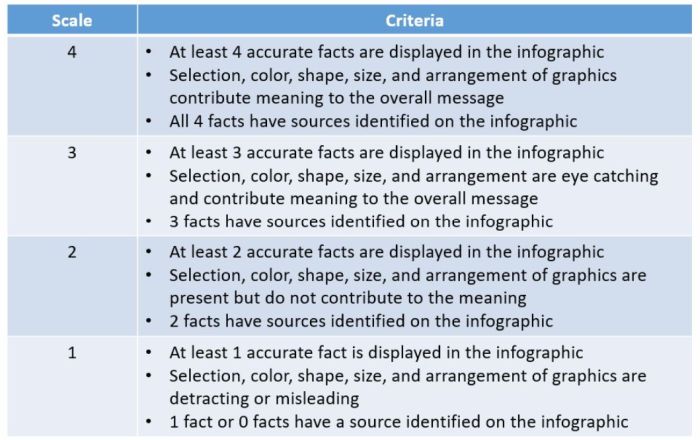

Determine the specific criteria or dimensions to assess in the assessment. These criteria should align with the learning objectives or outcomes to be evaluated. These criteria typically form the rows in a rubric grid and describe the skills, knowledge, or behavior to be demonstrated. The set of criteria may include, for example, the idea/content, quality of arguments, organization, grammar, citations and/or creativity in writing. These criteria may form separate rows or be compiled in a single row depending on the type of rubric.

(See row headers of Figure 1 )

Create a scale of performance levels that describe the degree of proficiency attained for each criterion. The scale typically has 4 to 5 levels (although there may be fewer levels depending on the type of rubrics used). The rubrics should also have meaningful labels (e.g., not meeting expectations, approaching expectations, meeting expectations, exceeding expectations). When assigning levels of performance, use inclusive language that can inculcate a growth mindset among students, especially when work may be otherwise deemed to not meet the mark. Some examples include, “Does not yet meet expectations,” “Considerable room for improvement,” “ Progressing,” “Approaching,” “Emerging,” “Needs more work,” instead of using terms like “Unacceptable,” “Fails,” “Poor,” or “Below Average.”

(See column headers of Figure 1 )

Develop a clear and concise descriptor for each combination of criterion and performance level. These descriptors should provide examples or explanations of what constitutes each level of performance for each criterion. Typically, instructors should start by describing the highest and lowest level of performance for that criterion and then describing intermediate performance for that criterion. It is important to keep the language uniform across all columns, e.g., use syntax and words that are aligned in each column for a given criteria.

(See cells of Figure 1 )

It is important to consider how each criterion is weighted and for each criterion to reflect the importance of learning objectives being tested. For example, if the primary goal of a research proposal is to test mastery of content and application of knowledge, these criteria should be weighted more heavily compared to other criteria (e.g., grammar, style of presentation). This can be done by associating a different scoring system for each criteria (e.g., Following a scale of 8-6-4-2 points for each level of performance in higher weight criteria and 4-3-2-1 points for each level of performance for lower weight criteria). Further, the number of points awarded across levels of performance should be evenly spaced (e.g., 10-8-6-4 instead of 10-6-3-1). Finally, if there is a letter grade associated with a particular assessment, consider how it relates to scores. For example, instead of having students receive an A only if they received the highest level of performance on each criterion, consider assigning an A grade to a range of scores (28 - 30 total points) or a combination of levels of performance (e.g., exceeds expectations on higher weight criteria and meets expectations on other criteria).

(See the numerical values in the column headers of Figure 1 )

Figure 1: Graphic describing the five basic elements of a rubric

Note : Consider using a template rubric that can be used to evaluate similar activities in the classroom to avoid the fatigue of developing multiple rubrics. Some tools include Rubistar or iRubric which provide suggested words for each criteria depending on the type of assessment. Additionally, the above format can be incorporated in rubrics that can be directly added in Canvas or in the grid view of rubrics in gradescope which are common grading tools. Alternately, tables within a Word processor or Spreadsheet may also be used to build a rubric. You may also adapt the example rubrics provided below to the specific learning goals for the assessment using the blank template rubrics we have provided against each type of rubric. Watch the linked video for a quick introduction to designing a rubric . Word document (docx) files linked below will automatically download to your device whereas pdf files will open in a new tab.

Types of Rubrics

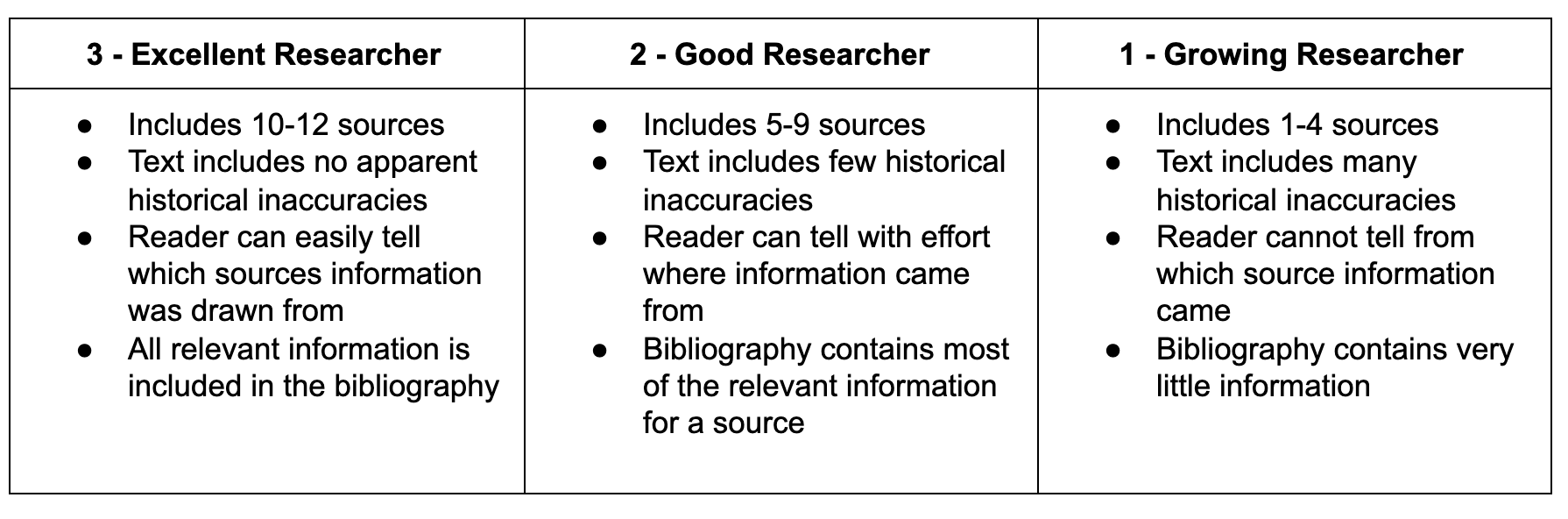

In these rubrics, one specifies at least two criteria and provides a separate score for each criterion. The steps outlined above for creating a rubric are typical for an analytic style rubric. Analytic rubrics are used to provide detailed feedback to students and help identify strengths as well as particular areas in need of improvement. These can be particularly useful when providing formative feedback to students, for student peer assessment and self-assessments, or for project-based summative assessments that evaluate student learning across multiple criteria. You may use a blank analytic rubric template (docx) or adapt an existing sample of an analytic rubric (pdf) .

Fig 2: Graphic describing a sample analytic rubric (adopted from George Mason University, 2013)

These are a subset of analytical rubrics that are typically used to assess student performance and engagement during a learning period but not the end product. Such rubrics are typically used to assess soft skills and behaviors that are less tangible (e.g., intercultural maturity, empathy, collaboration skills). These rubrics are useful in assessing the extent to which students develop a particular skill, ability, or value in experiential learning based programs or skills. They are grounded in the theory of development (King, 2005). Examples include an intercultural knowledge and competence rubric (docx) and a global learning rubric (docx) .

These rubrics consider all criteria evaluated on one scale, providing a single score that gives an overall impression of a student’s performance on an assessment.These rubrics also emphasize the overall quality of a student’s work, rather than delineating shortfalls of their work. However, a limitation of the holistic rubrics is that they are not useful for providing specific, nuanced feedback or to identify areas of improvement. Thus, they might be useful when grading summative assessments in which students have previously received detailed feedback using analytic or single-point rubrics. They may also be used to provide quick formative feedback for smaller assignments where not more than 2-3 criteria are being tested at once. Try using our blank holistic rubric template docx) or adapt an existing sample of holistic rubric (pdf) .

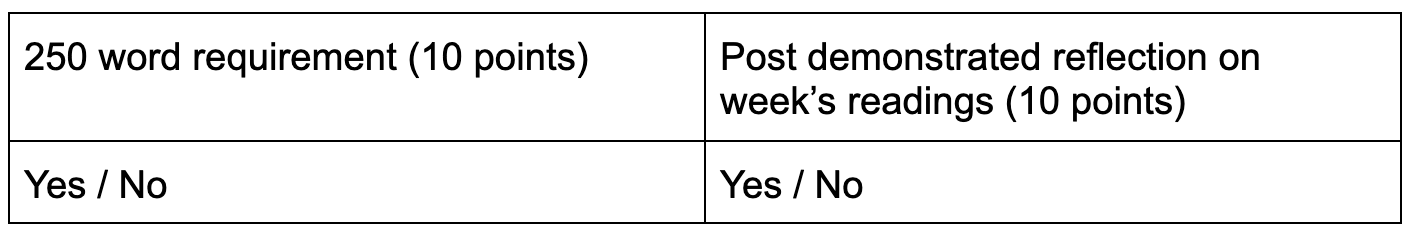

Fig 3: Graphic describing a sample holistic rubric (adopted from Teaching Commons, DePaul University)

These rubrics contain only two levels of performance (e.g., yes/no, present/absent) across a longer list of criteria (beyond 5 levels). Checklist rubrics have the advantage of providing a quick assessment of criteria given the binary assessment of criteria that are either met or are not met. Consequently, they are preferable when initiating self- or peer-assessments of learning given that it simplifies evaluations to be more objective and criteria can elicit only one of two responses allowing uniform and quick grading. For similar reasons, such rubrics are useful for faculty in providing quick formative feedback since it immediately highlights the specific criteria to improve on. Such rubrics are also used in grading summative assessments in courses utilizing alternative grading systems such as specifications grading, contract grading or a credit/no credit grading system wherein a minimum threshold of performance has to be met for the assessment. Having said that, developing rubrics from existing analytical rubrics may require considerable investment upfront given that criteria have to be phrased in a way that can only elicit binary responses. Here is a link to the checklist rubric template (docx) .

Fig. 4: Graphic describing a sample checklist rubric

A single point rubric is a modified version of a checklist style rubric, in that it specifies a single column of criteria. However, rather than only indicating whether expectations are met or not, as happens in a checklist rubric, a single point rubric allows instructors to specify ways in which criteria exceeds or does not meet expectations. Here the criteria to be tested are laid out in a central column describing the average expectation for the assignment. Instructors indicate areas of improvement on the left side of the criteria, whereas areas of strength in student performance are indicated on the right side. These types of rubrics provide flexibility in scoring, and are typically used in courses with alternative grading systems such as ungrading or contract grading. However, they do require the instructors to provide detailed feedback for each student, which can be unfeasible for assessments in large classes. Here is a link to the single point rubric template (docx) .

Fig. 5 Graphic describing a single point rubric (adopted from Teaching Commons, DePaul University)

Best Practices for Designing and Implementing Rubrics

When designing the rubric format, descriptors and criteria should be presented in a way that is compatible with screen readers and reading assistive technology. For example, avoid using only color, jargon, or complex terminology to convey information. In case you do use color, pictures or graphics, try providing alternative formats for rubrics, such as plain text documents. Explore resources from the CU Digital Accessibility Office to learn more.

Co-creating rubrics can help students to engage in higher-order thinking skills such as analysis and evaluation. Further, it allows students to take ownership of their own learning by determining the criteria of their work they aspire towards. For graduate classes or upper-level students, one way of doing this may be to provide learning outcomes of the project, and let students develop the rubric on their own. However, students in introductory classes may need more scaffolding by providing them a draft and leaving room for modification (Stevens & Levi 2013). Watch the linked video for tips on co-creating rubrics with students . Further, involving teaching assistants in designing a rubric can help in getting feedback on expectations for an assessment prior to implementing and norming a rubric.

When first designing a rubric, it is important to compare grades awarded for the same assessment by multiple graders to make sure the criteria are applied uniformly and reliably for the same level of performance. Further, ensure that the levels of performance in student work can be adequately distinguished using a rubric. Such a norming protocol is particularly important to also do at the start of any course in which multiple graders use the same rubric to grade an assessment (e.g., recitation sections, lab sections, teaching team). Here, instructors may select a subset of assignments that all graders evaluate using the same rubric, followed by a discussion to identify any discrepancies in criteria applied and ways to address them. Such strategies can make the rubrics more reliable, effective, and clear.

Sharing the rubric with students prior to an assessment can help familiarize students with an instructor’s expectations. This can help students master their learning outcomes by guiding their work in the appropriate direction and increase student motivation. Further, providing the rubric to students can help encourage metacognition and ability to self-assess learning.

Sample Rubrics

Below are links to rubric templates designed by a team of experts assembled by the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) to assess 16 major learning goals. These goals are a part of the Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE) program. All of these examples are analytic rubrics and have detailed criteria to test specific skills. However, since any given assessment typically tests multiple skills, instructors are encouraged to develop their own rubric by utilizing criteria picked from a combination of the rubrics linked below.

- Civic knowledge and engagement-local and global

- Creative thinking

- Critical thinking

- Ethical reasoning

- Foundations and skills for lifelong learning

- Information literacy

- Integrative and applied learning

- Intercultural knowledge and competence

- Inquiry and analysis

- Oral communication

- Problem solving

- Quantitative literacy

- Written Communication

Note : Clicking on the above links will automatically download them to your device in Microsoft Word format. These links have been created and are hosted by Kansas State University . Additional information regarding the VALUE Rubrics may be found on the AAC&U homepage .

Below are links to sample rubrics that have been developed for different types of assessments. These rubrics follow the analytical rubric template, unless mentioned otherwise. However, these rubrics can be modified into other types of rubrics (e.g., checklist, holistic or single point rubrics) based on the grading system and goal of assessment (e.g., formative or summative). As mentioned previously, these rubrics can be modified using the blank template provided.

- Oral presentations

- Painting Portfolio (single-point rubric)

- Research Paper

- Video Storyboard

Additional information:

Office of Assessment and Curriculum Support. (n.d.). Creating and using rubrics . University of Hawai’i, Mānoa

Calkins, C., & Winkelmes, M. A. (2018). A teaching method that boosts UNLV student retention . UNLV Best Teaching Practices Expo , 3.

Fraile, J., Panadero, E., & Pardo, R. (2017). Co-creating rubrics: The effects on self-regulated learning, self-efficacy and performance of establishing assessment criteria with students. Studies In Educational Evaluation , 53, 69-76

Haugnes, N., & Russell, J. L. (2016). Don’t box me in: Rubrics for àrtists and Designers . To Improve the Academy , 35 (2), 249–283.

Jonsson, A. (2014). Rubrics as a way of providing transparency in assessment , Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education , 39(7), 840-852

McCartin, L. (2022, February 1). Rubrics! an equity-minded practice . University of Northern Colorado

Shapiro, S., Farrelly, R., & Tomaš, Z. (2023). Chapter 4: Effective and Equitable Assignments and Assessments. Fostering International Student Success in higher education (pp, 61-87, second edition). TESOL Press.

Stevens, D. D., & Levi, A. J. (2013). Introduction to rubrics: An assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning (second edition). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Teaching Commons (n.d.). Types of Rubrics . DePaul University

Teaching Resources (n.d.). Rubric best practices, examples, and templates . NC State University

Winkelmes, M., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., & Weavil, K.H. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college students’ success . Peer Review , 8(1/2), 31-36.

Weisz, C., Richard, D., Oleson, K., Winkelmes, M.A., Powley, C., Sadik, A., & Stone, B. (in progress, 2023). Transparency, confidence, belonging and skill development among 400 community college students in the state of Washington .

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2009). Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE) .

Canvas Community. (2021, August 24). How do I add a rubric in a course? Canvas LMS Community.

Center for Teaching & Learning. (2021, March 03). Overview of Rubrics . University of Colorado, Boulder

Center for Teaching & Learning. (2021, March 18). Best practices to co-create rubrics with students . University of Colorado, Boulder.

Chase, D., Ferguson, J. L., & Hoey, J. J. (2014). Assessment in creative disciplines: Quantifying and qualifying the aesthetic . Common Ground Publishing.

Feldman, J. (2018). Grading for equity: What it is, why it matters, and how it can transform schools and classrooms . Corwin Press, CA.

Gradescope (n.d.). Instructor: Assignment - Grade Submissions . Gradescope Help Center.

Henning, G., Baker, G., Jankowski, N., Lundquist, A., & Montenegro, E. (Eds.). (2022). Reframing assessment to center equity . Stylus Publishing.

King, P. M. & Baxter Magolda, M. B. (2005). A developmental model of intercultural maturity . Journal of College Student Development . 46(2), 571-592.

Selke, M. J. G. (2013). Rubric assessment goes to college: Objective, comprehensive evaluation of student work. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

The Institute for Habits of Mind. (2023, January 9). Creativity Rubrics - The Institute for Habits of Mind .

- Assessment in Large Enrollment Classes

- Classroom Assessment Techniques

- Creating and Using Learning Outcomes

- Early Feedback

- Five Misconceptions on Writing Feedback

- Formative Assessments

- Frequent Feedback

- Online and Remote Exams

- Student Learning Outcomes Assessment

- Student Peer Assessment

- Student Self-assessment

- Summative Assessments: Best Practices

- Summative Assessments: Types

- Assessing & Reflecting on Teaching

- Departmental Teaching Evaluation

- Equity in Assessment

- Glossary of Terms

- Attendance Policies

- Books We Recommend

- Classroom Management

- Community-Developed Resources

- Compassion & Self-Compassion

- Course Design & Development

- Course-in-a-box for New CU Educators

- Enthusiasm & Teaching

- First Day Tips

- Flexible Teaching

- Grants & Awards

- Inclusivity

- Learner Motivation

- Making Teaching & Learning Visible

- National Center for Faculty Development & Diversity

- Open Education

- Student Support Toolkit

- Sustainaiblity

- TA/Instructor Agreement

- Teaching & Learning in the Age of AI

- Teaching Well with Technology

Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Creating and using rubrics.

A rubric describes the criteria that will be used to evaluate a specific task, such as a student writing assignment, poster, oral presentation, or other project. Rubrics allow instructors to communicate expectations to students, allow students to check in on their progress mid-assignment, and can increase the reliability of scores. Research suggests that when rubrics are used on an instructional basis (for instance, included with an assignment prompt for reference), students tend to utilize and appreciate them (Reddy and Andrade, 2010).

Rubrics generally exist in tabular form and are composed of:

- A description of the task that is being evaluated,

- The criteria that is being evaluated (row headings),

- A rating scale that demonstrates different levels of performance (column headings), and

- A description of each level of performance for each criterion (within each box of the table).

When multiple individuals are grading, rubrics also help improve the consistency of scoring across all graders. Instructors should insure that the structure, presentation, consistency, and use of their rubrics pass rigorous standards of validity , reliability , and fairness (Andrade, 2005).

Major Types of Rubrics

There are two major categories of rubrics:

- Holistic : In this type of rubric, a single score is provided based on raters’ overall perception of the quality of the performance. Holistic rubrics are useful when only one attribute is being evaluated, as they detail different levels of performance within a single attribute. This category of rubric is designed for quick scoring but does not provide detailed feedback. For these rubrics, the criteria may be the same as the description of the task.

- Analytic : In this type of rubric, scores are provided for several different criteria that are being evaluated. Analytic rubrics provide more detailed feedback to students and instructors about their performance. Scoring is usually more consistent across students and graders with analytic rubrics.

Rubrics utilize a scale that denotes level of success with a particular assignment, usually a 3-, 4-, or 5- category grid:

Figure 1: Grading Rubrics: Sample Scales (Brown Sheridan Center)

Sample Rubrics

Instructors can consider a sample holistic rubric developed for an English Writing Seminar course at Yale.

The Association of American Colleges and Universities also has a number of free (non-invasive free account required) analytic rubrics that can be downloaded and modified by instructors. These 16 VALUE rubrics enable instructors to measure items such as inquiry and analysis, critical thinking, written communication, oral communication, quantitative literacy, teamwork, problem-solving, and more.

Recommendations

The following provides a procedure for developing a rubric, adapted from Brown’s Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning :

- Define the goal and purpose of the task that is being evaluated - Before constructing a rubric, instructors should review their learning outcomes associated with a given assignment. Are skills, content, and deeper conceptual knowledge clearly defined in the syllabus , and do class activities and assignments work towards intended outcomes? The rubric can only function effectively if goals are clear and student work progresses towards them.

- Decide what kind of rubric to use - The kind of rubric used may depend on the nature of the assignment, intended learning outcomes (for instance, does the task require the demonstration of several different skills?), and the amount and kind of feedback students will receive (for instance, is the task a formative or a summative assessment ?). Instructors can read the above, or consider “Additional Resources” for kinds of rubrics.

- Define the criteria - Instructors can review their learning outcomes and assessment parameters to determine specific criteria for the rubric to cover. Instructors should consider what knowledge and skills are required for successful completion, and create a list of criteria that assess outcomes across different vectors (comprehensiveness, maturity of thought, revisions, presentation, timeliness, etc). Criteria should be distinct and clearly described, and ideally, not surpass seven in number.

- Define the rating scale to measure levels of performance - Whatever rating scale instructors choose, they should insure that it is clear, and review it in-class to field student question and concerns. Instructors can consider if the scale will include descriptors or only be numerical, and might include prompts on the rubric for achieving higher achievement levels. Rubrics typically include 3-5 levels in their rating scales (see Figure 1 above).

- Write descriptions for each performance level of the rating scale - Each level should be accompanied by a descriptive paragraph that outlines ideals for each level, lists or names all performance expectations within the level, and if possible, provides a detail or example of ideal performance within each level. Across the rubric, descriptions should be parallel, observable, and measurable.

- Test and revise the rubric - The rubric can be tested before implementation, by arranging for writing or testing conditions with several graders or TFs who can use the rubric together. After grading with the rubric, graders might grade a similar set of materials without the rubric to assure consistency. Instructors can consider discrepancies, share the rubric and results with faculty colleagues for further opinions, and revise the rubric for use in class. Instructors might also seek out colleagues’ rubrics as well, for comparison. Regarding course implementation, instructors might consider passing rubrics out during the first class, in order to make grading expectations clear as early as possible. Rubrics should fit on one page, so that descriptions and criteria are viewable quickly and simultaneously. During and after a class or course, instructors can collect feedback on the rubric’s clarity and effectiveness from TFs and even students through anonymous surveys. Comparing scores and quality of assignments with parallel or previous assignments that did not include a rubric can reveal effectiveness as well. Instructors should feel free to revise a rubric following a course too, based on student performance and areas of confusion.

Additional Resources

Cox, G. C., Brathwaite, B. H., & Morrison, J. (2015). The Rubric: An assessment tool to guide students and markers. Advances in Higher Education, 149-163.

Creating and Using Rubrics - Carnegie Mellon Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and & Educational Innovation

Creating a Rubric - UC Denver Center for Faculty Development

Grading Rubric Design - Brown University Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning

Moskal, B. M. (2000). Scoring rubrics: What, when and how? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 7(3).

Quinlan A. M., (2011) A Complete Guide to Rubrics: Assessment Made Easy for Teachers of K-college 2nd edition, Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Andrade, H. (2005). Teaching with Rubrics: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. College Teaching 53(1):27-30.

Reddy, Y. M., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448.

Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning , Brown University

Downloads

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

Instructional Enhancement Fund

The Instructional Enhancement Fund (IEF) awards grants of up to $500 to support the timely integration of new learning activities into an existing undergraduate or graduate course. All Yale instructors of record, including tenured and tenure-track faculty, clinical instructional faculty, lecturers, lectors, and part-time acting instructors (PTAIs), are eligible to apply. Award decisions are typically provided within two weeks to help instructors implement ideas for the current semester.

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

- Faculty and Staff

Assessment and Curriculum Support Center

Creating and using rubrics.

Last Updated: 4 March 2024. Click here to view archived versions of this page.

On this page:

- What is a rubric?

- Why use a rubric?

- What are the parts of a rubric?

- Developing a rubric

- Sample rubrics

- Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration

- Suggestions for using rubrics in courses

- Equity-minded considerations for rubric development

- Tips for developing a rubric

- Additional resources & sources consulted

Note: The information and resources contained here serve only as a primers to the exciting and diverse perspectives in the field today. This page will be continually updated to reflect shared understandings of equity-minded theory and practice in learning assessment.

1. What is a rubric?

A rubric is an assessment tool often shaped like a matrix, which describes levels of achievement in a specific area of performance, understanding, or behavior.

There are two main types of rubrics:

Analytic Rubric : An analytic rubric specifies at least two characteristics to be assessed at each performance level and provides a separate score for each characteristic (e.g., a score on “formatting” and a score on “content development”).

- Advantages: provides more detailed feedback on student performance; promotes consistent scoring across students and between raters

- Disadvantages: more time consuming than applying a holistic rubric

- You want to see strengths and weaknesses.

- You want detailed feedback about student performance.

Holistic Rubric: A holistic rubrics provide a single score based on an overall impression of a student’s performance on a task.

- Advantages: quick scoring; provides an overview of student achievement; efficient for large group scoring

- Disadvantages: does not provided detailed information; not diagnostic; may be difficult for scorers to decide on one overall score

- You want a quick snapshot of achievement.

- A single dimension is adequate to define quality.

2. Why use a rubric?

- A rubric creates a common framework and language for assessment.

- Complex products or behaviors can be examined efficiently.

- Well-trained reviewers apply the same criteria and standards.

- Rubrics are criterion-referenced, rather than norm-referenced. Raters ask, “Did the student meet the criteria for level 5 of the rubric?” rather than “How well did this student do compared to other students?”

- Using rubrics can lead to substantive conversations among faculty.

- When faculty members collaborate to develop a rubric, it promotes shared expectations and grading practices.

Faculty members can use rubrics for program assessment. Examples:

The English Department collected essays from students in all sections of English 100. A random sample of essays was selected. A team of faculty members evaluated the essays by applying an analytic scoring rubric. Before applying the rubric, they “normed”–that is, they agreed on how to apply the rubric by scoring the same set of essays and discussing them until consensus was reached (see below: “6. Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration”). Biology laboratory instructors agreed to use a “Biology Lab Report Rubric” to grade students’ lab reports in all Biology lab sections, from 100- to 400-level. At the beginning of each semester, instructors met and discussed sample lab reports. They agreed on how to apply the rubric and their expectations for an “A,” “B,” “C,” etc., report in 100-level, 200-level, and 300- and 400-level lab sections. Every other year, a random sample of students’ lab reports are selected from 300- and 400-level sections. Each of those reports are then scored by a Biology professor. The score given by the course instructor is compared to the score given by the Biology professor. In addition, the scores are reported as part of the program’s assessment report. In this way, the program determines how well it is meeting its outcome, “Students will be able to write biology laboratory reports.”

3. What are the parts of a rubric?

Rubrics are composed of four basic parts. In its simplest form, the rubric includes:

- A task description . The outcome being assessed or instructions students received for an assignment.

- The characteristics to be rated (rows) . The skills, knowledge, and/or behavior to be demonstrated.

- Beginning, approaching, meeting, exceeding

- Emerging, developing, proficient, exemplary

- Novice, intermediate, intermediate high, advanced

- Beginning, striving, succeeding, soaring

- Also called a “performance description.” Explains what a student will have done to demonstrate they are at a given level of mastery for a given characteristic.

4. Developing a rubric

Step 1: Identify what you want to assess

Step 2: Identify the characteristics to be rated (rows). These are also called “dimensions.”

- Specify the skills, knowledge, and/or behaviors that you will be looking for.

- Limit the characteristics to those that are most important to the assessment.

Step 3: Identify the levels of mastery/scale (columns).

Tip: Aim for an even number (4 or 6) because when an odd number is used, the middle tends to become the “catch-all” category.

Step 4: Describe each level of mastery for each characteristic/dimension (cells).

- Describe the best work you could expect using these characteristics. This describes the top category.

- Describe an unacceptable product. This describes the lowest category.

- Develop descriptions of intermediate-level products for intermediate categories.

Important: Each description and each characteristic should be mutually exclusive.

Step 5: Test rubric.

- Apply the rubric to an assignment.

- Share with colleagues.

Tip: Faculty members often find it useful to establish the minimum score needed for the student work to be deemed passable. For example, faculty members may decided that a “1” or “2” on a 4-point scale (4=exemplary, 3=proficient, 2=marginal, 1=unacceptable), does not meet the minimum quality expectations. We encourage a standard setting session to set the score needed to meet expectations (also called a “cutscore”). Monica has posted materials from standard setting workshops, one offered on campus and the other at a national conference (includes speaker notes with the presentation slides). They may set their criteria for success as 90% of the students must score 3 or higher. If assessment study results fall short, action will need to be taken.

Step 6: Discuss with colleagues. Review feedback and revise.

Important: When developing a rubric for program assessment, enlist the help of colleagues. Rubrics promote shared expectations and consistent grading practices which benefit faculty members and students in the program.

5. Sample rubrics

Rubrics are on our Rubric Bank page and in our Rubric Repository (Graduate Degree Programs) . More are available at the Assessment and Curriculum Support Center in Crawford Hall (hard copy).

These open as Word documents and are examples from outside UH.

- Group Participation (analytic rubric)

- Participation (holistic rubric)

- Design Project (analytic rubric)

- Critical Thinking (analytic rubric)

- Media and Design Elements (analytic rubric; portfolio)

- Writing (holistic rubric; portfolio)

6. Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration

When using a rubric for program assessment purposes, faculty members apply the rubric to pieces of student work (e.g., reports, oral presentations, design projects). To produce dependable scores, each faculty member needs to interpret the rubric in the same way. The process of training faculty members to apply the rubric is called “norming.” It’s a way to calibrate the faculty members so that scores are accurate and consistent across the faculty. Below are directions for an assessment coordinator carrying out this process.

Suggested materials for a scoring session:

- Copies of the rubric

- Copies of the “anchors”: pieces of student work that illustrate each level of mastery. Suggestion: have 6 anchor pieces (2 low, 2 middle, 2 high)

- Score sheets

- Extra pens, tape, post-its, paper clips, stapler, rubber bands, etc.

Hold the scoring session in a room that:

- Allows the scorers to spread out as they rate the student pieces

- Has a chalk or white board, smart board, or flip chart

- Describe the purpose of the activity, stressing how it fits into program assessment plans. Explain that the purpose is to assess the program, not individual students or faculty, and describe ethical guidelines, including respect for confidentiality and privacy.

- Describe the nature of the products that will be reviewed, briefly summarizing how they were obtained.

- Describe the scoring rubric and its categories. Explain how it was developed.

- Analytic: Explain that readers should rate each dimension of an analytic rubric separately, and they should apply the criteria without concern for how often each score (level of mastery) is used. Holistic: Explain that readers should assign the score or level of mastery that best describes the whole piece; some aspects of the piece may not appear in that score and that is okay. They should apply the criteria without concern for how often each score is used.

- Give each scorer a copy of several student products that are exemplars of different levels of performance. Ask each scorer to independently apply the rubric to each of these products, writing their ratings on a scrap sheet of paper.

- Once everyone is done, collect everyone’s ratings and display them so everyone can see the degree of agreement. This is often done on a blackboard, with each person in turn announcing his/her ratings as they are entered on the board. Alternatively, the facilitator could ask raters to raise their hands when their rating category is announced, making the extent of agreement very clear to everyone and making it very easy to identify raters who routinely give unusually high or low ratings.

- Guide the group in a discussion of their ratings. There will be differences. This discussion is important to establish standards. Attempt to reach consensus on the most appropriate rating for each of the products being examined by inviting people who gave different ratings to explain their judgments. Raters should be encouraged to explain by making explicit references to the rubric. Usually consensus is possible, but sometimes a split decision is developed, e.g., the group may agree that a product is a “3-4” split because it has elements of both categories. This is usually not a problem. You might allow the group to revise the rubric to clarify its use but avoid allowing the group to drift away from the rubric and learning outcome(s) being assessed.

- Once the group is comfortable with how the rubric is applied, the rating begins. Explain how to record ratings using the score sheet and explain the procedures. Reviewers begin scoring.

- Are results sufficiently reliable?

- What do the results mean? Are we satisfied with the extent of students’ learning?

- Who needs to know the results?

- What are the implications of the results for curriculum, pedagogy, or student support services?

- How might the assessment process, itself, be improved?

7. Suggestions for using rubrics in courses

- Use the rubric to grade student work. Hand out the rubric with the assignment so students will know your expectations and how they’ll be graded. This should help students master your learning outcomes by guiding their work in appropriate directions.

- Use a rubric for grading student work and return the rubric with the grading on it. Faculty save time writing extensive comments; they just circle or highlight relevant segments of the rubric. Some faculty members include room for additional comments on the rubric page, either within each section or at the end.

- Develop a rubric with your students for an assignment or group project. Students can the monitor themselves and their peers using agreed-upon criteria that they helped develop. Many faculty members find that students will create higher standards for themselves than faculty members would impose on them.

- Have students apply your rubric to sample products before they create their own. Faculty members report that students are quite accurate when doing this, and this process should help them evaluate their own projects as they are being developed. The ability to evaluate, edit, and improve draft documents is an important skill.

- Have students exchange paper drafts and give peer feedback using the rubric. Then, give students a few days to revise before submitting the final draft to you. You might also require that they turn in the draft and peer-scored rubric with their final paper.

- Have students self-assess their products using the rubric and hand in their self-assessment with the product; then, faculty members and students can compare self- and faculty-generated evaluations.

8. Equity-minded considerations for rubric development

Ensure transparency by making rubric criteria public, explicit, and accessible

Transparency is a core tenet of equity-minded assessment practice. Students should know and understand how they are being evaluated as early as possible.

- Ensure the rubric is publicly available & easily accessible. We recommend publishing on your program or department website.

- Have course instructors introduce and use the program rubric in their own courses. Instructors should explain to students connections between the rubric criteria and the course and program SLOs.

- Write rubric criteria using student-focused and culturally-relevant language to ensure students understand the rubric’s purpose, the expectations it sets, and how criteria will be applied in assessing their work.

- For example, instructors can provide annotated examples of student work using the rubric language as a resource for students.

Meaningfully involve students and engage multiple perspectives

Rubrics created by faculty alone risk perpetuating unseen biases as the evaluation criteria used will inherently reflect faculty perspectives, values, and assumptions. Including students and other stakeholders in developing criteria helps to ensure performance expectations are aligned between faculty, students, and community members. Additional perspectives to be engaged might include community members, alumni, co-curricular faculty/staff, field supervisors, potential employers, or current professionals. Consider the following strategies to meaningfully involve students and engage multiple perspectives:

- Have students read each evaluation criteria and talk out loud about what they think it means. This will allow you to identify what language is clear and where there is still confusion.

- Ask students to use their language to interpret the rubric and provide a student version of the rubric.

- If you use this strategy, it is essential to create an inclusive environment where students and faculty have equal opportunity to provide input.

- Be sure to incorporate feedback from faculty and instructors who teach diverse courses, levels, and in different sub-disciplinary topics. Faculty and instructors who teach introductory courses have valuable experiences and perspectives that may differ from those who teach higher-level courses.

- Engage multiple perspectives including co-curricular faculty/staff, alumni, potential employers, and community members for feedback on evaluation criteria and rubric language. This will ensure evaluation criteria reflect what is important for all stakeholders.

- Elevate historically silenced voices in discussions on rubric development. Ensure stakeholders from historically underrepresented communities have their voices heard and valued.

Honor students’ strengths in performance descriptions

When describing students’ performance at different levels of mastery, use language that describes what students can do rather than what they cannot do. For example:

- Instead of: Students cannot make coherent arguments consistently.

- Use: Students can make coherent arguments occasionally.

9. Tips for developing a rubric

- Find and adapt an existing rubric! It is rare to find a rubric that is exactly right for your situation, but you can adapt an already existing rubric that has worked well for others and save a great deal of time. A faculty member in your program may already have a good one.

- Evaluate the rubric . Ask yourself: A) Does the rubric relate to the outcome(s) being assessed? (If yes, success!) B) Does it address anything extraneous? (If yes, delete.) C) Is the rubric useful, feasible, manageable, and practical? (If yes, find multiple ways to use the rubric: program assessment, assignment grading, peer review, student self assessment.)

- Collect samples of student work that exemplify each point on the scale or level. A rubric will not be meaningful to students or colleagues until the anchors/benchmarks/exemplars are available.

- Expect to revise.

- When you have a good rubric, SHARE IT!

10. Additional resources & sources consulted:

Rubric examples:

- Rubrics primarily for undergraduate outcomes and programs

- Rubric repository for graduate degree programs

Workshop presentation slides and handouts:

- Workshop handout (Word document)

- How to Use a Rubric for Program Assessment (2010)

- Techniques for Using Rubrics in Program Assessment by guest speaker Dannelle Stevens (2010)

- Rubrics: Save Grading Time & Engage Students in Learning by guest speaker Dannelle Stevens (2009)

- Rubric Library , Institutional Research, Assessment & Planning, California State University-Fresno

- The Basics of Rubrics [PDF], Schreyer Institute, Penn State

- Creating Rubrics , Teaching Methods and Management, TeacherVision

- Allen, Mary – University of Hawai’i at Manoa Spring 2008 Assessment Workshops, May 13-14, 2008 [available at the Assessment and Curriculum Support Center]

- Mertler, Craig A. (2001). Designing scoring rubrics for your classroom. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 7(25).

- NPEC Sourcebook on Assessment: Definitions and Assessment Methods for Communication, Leadership, Information Literacy, Quantitative Reasoning, and Quantitative Skills . [PDF] (June 2005)

Contributors: Monica Stitt-Bergh, Ph.D., Yao Z. Hill Ph.D., TJ Buckley.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

How do You Use Social Media? Be entered to win a $50 gift card!

15 Helpful Scoring Rubric Examples for All Grades and Subjects

In the end, they actually make grading easier.