How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples, frequently asked questions.

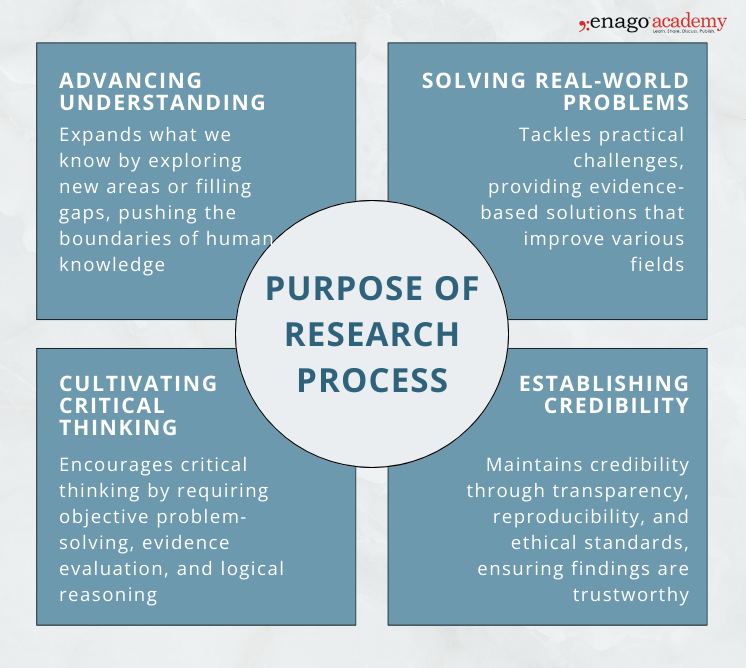

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is an AI academic writing assistant that helps authors write better and faster with real-time writing suggestions and in-depth checks for language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of published scholarly articles and 20+ years of STM experience, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to Paperpal Copilot and premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks, submission readiness and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Chemistry Terms: 7 Commonly Confused Words in Chemistry Manuscripts

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., publish research papers: 9 steps for successful publications , what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how..., 6 tips for post-doc researchers to take their..., presenting research data effectively through tables and figures, ethics in science: importance, principles & guidelines .

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 9. The Conclusion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The conclusion is intended to help the reader understand why your research should matter to them after they have finished reading the paper. A conclusion is not merely a summary of the main topics covered or a re-statement of your research problem, but a synthesis of key points and, if applicable, where you recommend new areas for future research. For most college-level research papers, one or two well-developed paragraphs is sufficient for a conclusion, although in some cases, more paragraphs may be required in summarizing key findings and their significance.

Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Importance of a Good Conclusion

A well-written conclusion provides you with important opportunities to demonstrate to the reader your understanding of the research problem. These include:

- Presenting the last word on the issues you raised in your paper . Just as the introduction gives a first impression to your reader, the conclusion offers a chance to leave a lasting impression. Do this, for example, by highlighting key findings in your analysis that advance new understanding about the research problem, that are unusual or unexpected, or that have important implications applied to practice.

- Summarizing your thoughts and conveying the larger significance of your study . The conclusion is an opportunity to succinctly re-emphasize the "So What?" question by placing the study within the context of how your research advances past research about the topic.

- Identifying how a gap in the literature has been addressed . The conclusion can be where you describe how a previously identified gap in the literature [described in your literature review section] has been filled by your research.

- Demonstrating the importance of your ideas . Don't be shy. The conclusion offers you the opportunity to elaborate on the impact and significance of your findings. This is particularly important if your study approached examining the research problem from an unusual or innovative perspective.

- Introducing possible new or expanded ways of thinking about the research problem . This does not refer to introducing new information [which should be avoided], but to offer new insight and creative approaches for framing or contextualizing the research problem based on the results of your study.

Bunton, David. “The Structure of PhD Conclusion Chapters.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 4 (July 2005): 207–224; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

The function of your paper's conclusion is to restate the main argument . It reminds the reader of the strengths of your main argument(s) and reiterates the most important evidence supporting those argument(s). Do this by stating clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem you investigated in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found in the literature. Make sure, however, that your conclusion is not simply a repetitive summary of the findings. This reduces the impact of the argument(s) you have developed in your essay.

When writing the conclusion to your paper, follow these general rules:

- Present your conclusions in clear, simple language. Re-state the purpose of your study, then describe how your findings differ or support those of other studies and why [i.e., what were the unique or new contributions your study made to the overall research about your topic?].

- Do not simply reiterate your findings or the discussion of your results. Provide a synthesis of arguments presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem and the overall objectives of your study.

- Indicate opportunities for future research if you haven't already done so in the discussion section of your paper. Highlighting the need for further research provides the reader with evidence that you have an in-depth awareness of the research problem and that further investigations should take place.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is presented well:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If, prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from the data.

The conclusion also provides a place for you to persuasively and succinctly restate the research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with all the information about the topic . Depending on the discipline you are writing in, the concluding paragraph may contain your reflections on the evidence presented. However, the nature of being introspective about the research you have conducted will depend on the topic and whether your professor wants you to express your observations in this way.

NOTE : If asked to think introspectively about the topics, do not delve into idle speculation. Being introspective means looking within yourself as an author to try and understand an issue more deeply, not to guess at possible outcomes or make up scenarios not supported by the evidence.

II. Developing a Compelling Conclusion

Although an effective conclusion needs to be clear and succinct, it does not need to be written passively or lack a compelling narrative. Strategies to help you move beyond merely summarizing the key points of your research paper may include any of the following strategies:

- If your essay deals with a critical, contemporary problem, warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem proactively.

- Recommend a specific course or courses of action that, if adopted, could address a specific problem in practice or in the development of new knowledge.

- Cite a relevant quotation or expert opinion already noted in your paper in order to lend authority and support to the conclusion(s) you have reached [a good place to look is research from your literature review].

- Explain the consequences of your research in a way that elicits action or demonstrates urgency in seeking change.

- Restate a key statistic, fact, or visual image to emphasize the most important finding of your paper.

- If your discipline encourages personal reflection, illustrate your concluding point by drawing from your own life experiences.

- Return to an anecdote, an example, or a quotation that you presented in your introduction, but add further insight derived from the findings of your study; use your interpretation of results to recast it in new or important ways.

- Provide a "take-home" message in the form of a succinct, declarative statement that you want the reader to remember about your study.

III. Problems to Avoid

Failure to be concise Your conclusion section should be concise and to the point. Conclusions that are too lengthy often have unnecessary information in them. The conclusion is not the place for details about your methodology or results. Although you should give a summary of what was learned from your research, this summary should be relatively brief, since the emphasis in the conclusion is on the implications, evaluations, insights, and other forms of analysis that you make. Strategies for writing concisely can be found here .

Failure to comment on larger, more significant issues In the introduction, your task was to move from the general [the field of study] to the specific [the research problem]. However, in the conclusion, your task is to move from a specific discussion [your research problem] back to a general discussion [i.e., how your research contributes new understanding or fills an important gap in the literature]. In short, the conclusion is where you should place your research within a larger context [visualize your paper as an hourglass--start with a broad introduction and review of the literature, move to the specific analysis and discussion, conclude with a broad summary of the study's implications and significance].

Failure to reveal problems and negative results Negative aspects of the research process should never be ignored. These are problems, deficiencies, or challenges encountered during your study should be summarized as a way of qualifying your overall conclusions. If you encountered negative or unintended results [i.e., findings that are validated outside the research context in which they were generated], you must report them in the results section and discuss their implications in the discussion section of your paper. In the conclusion, use your summary of the negative results as an opportunity to explain their possible significance and/or how they may form the basis for future research.

Failure to provide a clear summary of what was learned In order to be able to discuss how your research fits within your field of study [and possibly the world at large], you need to summarize briefly and succinctly how it contributes to new knowledge or a new understanding about the research problem. This element of your conclusion may be only a few sentences long.

Failure to match the objectives of your research Often research objectives in the social sciences change while the research is being carried out. This is not a problem unless you forget to go back and refine the original objectives in your introduction. As these changes emerge they must be documented so that they accurately reflect what you were trying to accomplish in your research [not what you thought you might accomplish when you began].

Resist the urge to apologize If you've immersed yourself in studying the research problem, you presumably should know a good deal about it [perhaps even more than your professor!]. Nevertheless, by the time you have finished writing, you may be having some doubts about what you have produced. Repress those doubts! Don't undermine your authority by saying something like, "This is just one approach to examining this problem; there may be other, much better approaches that...." The overall tone of your conclusion should convey confidence to the reader.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Concluding Paragraphs. College Writing Center at Meramec. St. Louis Community College; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Leibensperger, Summer. Draft Your Conclusion. Academic Center, the University of Houston-Victoria, 2003; Make Your Last Words Count. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin Madison; Miquel, Fuster-Marquez and Carmen Gregori-Signes. “Chapter Six: ‘Last but Not Least:’ Writing the Conclusion of Your Paper.” In Writing an Applied Linguistics Thesis or Dissertation: A Guide to Presenting Empirical Research . John Bitchener, editor. (Basingstoke,UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 93-105; Tips for Writing a Good Conclusion. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Writing Conclusions. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Writing: Considering Structure and Organization. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Don't Belabor the Obvious!

Avoid phrases like "in conclusion...," "in summary...," or "in closing...." These phrases can be useful, even welcome, in oral presentations. But readers can see by the tell-tale section heading and number of pages remaining to read, when an essay is about to end. You'll irritate your readers if you belabor the obvious.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Another Writing Tip

New Insight, Not New Information!

Don't surprise the reader with new information in your conclusion that was never referenced anywhere else in the paper and, as such, the conclusion rarely has citations to sources. If you have new information to present, add it to the discussion or other appropriate section of the paper. Note that, although no actual new information is introduced, the conclusion, along with the discussion section, is where you offer your most "original" contributions in the paper; the conclusion is where you describe the value of your research, demonstrate that you understand the material that you’ve presented, and locate your findings within the larger context of scholarship on the topic, including describing how your research contributes new insights or valuable insight to that scholarship.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

- << Previous: Limitations of the Study

- Next: Appendices >>

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 9:59 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

The research process, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Draw Conclusions

As a writer, you are presenting your viewpoint, opinions, evidence, etc. for others to review, so you must take on this task with maturity, courage and thoughtfulness. Remember, you are adding to the discourse community with every research paper that you write. This is a privilege and an opportunity to share your point of view with the world at large in an academic setting.

Because research generates further research, the conclusions you draw from your research are important. As a researcher, you depend on the integrity of the research that precedes your own efforts, and researchers depend on each other to draw valid conclusions.

To test the validity of your conclusions, you will have to review both the content of your paper and the way in which you arrived at the content. You may ask yourself questions, such as the ones presented below, to detect any weak areas in your paper, so you can then make those areas stronger. Notice that some of the questions relate to your process, others to your sources, and others to how you arrived at your conclusions.

Checklist for Evaluating Your Conclusions

Key takeaways.

- Because research generates further research, the conclusions you draw from your research are important.

- To test the validity of your conclusions, you will have to review both the content of your paper and the way in which you arrived at the content.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Conclusions

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain the functions of conclusions, offer strategies for writing effective ones, help you evaluate conclusions you’ve drafted, and suggest approaches to avoid.

About conclusions

Introductions and conclusions can be difficult to write, but they’re worth investing time in. They can have a significant influence on a reader’s experience of your paper.

Just as your introduction acts as a bridge that transports your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. Such a conclusion will help them see why all your analysis and information should matter to them after they put the paper down.

Your conclusion is your chance to have the last word on the subject. The conclusion allows you to have the final say on the issues you have raised in your paper, to synthesize your thoughts, to demonstrate the importance of your ideas, and to propel your reader to a new view of the subject. It is also your opportunity to make a good final impression and to end on a positive note.

Your conclusion can go beyond the confines of the assignment. The conclusion pushes beyond the boundaries of the prompt and allows you to consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of your findings.

Your conclusion should make your readers glad they read your paper. Your conclusion gives your reader something to take away that will help them see things differently or appreciate your topic in personally relevant ways. It can suggest broader implications that will not only interest your reader, but also enrich your reader’s life in some way. It is your gift to the reader.

Strategies for writing an effective conclusion

One or more of the following strategies may help you write an effective conclusion:

- Play the “So What” Game. If you’re stuck and feel like your conclusion isn’t saying anything new or interesting, ask a friend to read it with you. Whenever you make a statement from your conclusion, ask the friend to say, “So what?” or “Why should anybody care?” Then ponder that question and answer it. Here’s how it might go: You: Basically, I’m just saying that education was important to Douglass. Friend: So what? You: Well, it was important because it was a key to him feeling like a free and equal citizen. Friend: Why should anybody care? You: That’s important because plantation owners tried to keep slaves from being educated so that they could maintain control. When Douglass obtained an education, he undermined that control personally. You can also use this strategy on your own, asking yourself “So What?” as you develop your ideas or your draft.

- Return to the theme or themes in the introduction. This strategy brings the reader full circle. For example, if you begin by describing a scenario, you can end with the same scenario as proof that your essay is helpful in creating a new understanding. You may also refer to the introductory paragraph by using key words or parallel concepts and images that you also used in the introduction.

- Synthesize, don’t summarize. Include a brief summary of the paper’s main points, but don’t simply repeat things that were in your paper. Instead, show your reader how the points you made and the support and examples you used fit together. Pull it all together.

- Include a provocative insight or quotation from the research or reading you did for your paper.

- Propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or questions for further study. This can redirect your reader’s thought process and help them to apply your info and ideas to their own life or to see the broader implications.

- Point to broader implications. For example, if your paper examines the Greensboro sit-ins or another event in the Civil Rights Movement, you could point out its impact on the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. A paper about the style of writer Virginia Woolf could point to her influence on other writers or on later feminists.

Strategies to avoid

- Beginning with an unnecessary, overused phrase such as “in conclusion,” “in summary,” or “in closing.” Although these phrases can work in speeches, they come across as wooden and trite in writing.

- Stating the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion.

- Introducing a new idea or subtopic in your conclusion.

- Ending with a rephrased thesis statement without any substantive changes.

- Making sentimental, emotional appeals that are out of character with the rest of an analytical paper.

- Including evidence (quotations, statistics, etc.) that should be in the body of the paper.

Four kinds of ineffective conclusions

- The “That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It” Conclusion. This conclusion just restates the thesis and is usually painfully short. It does not push the ideas forward. People write this kind of conclusion when they can’t think of anything else to say. Example: In conclusion, Frederick Douglass was, as we have seen, a pioneer in American education, proving that education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

- The “Sherlock Holmes” Conclusion. Sometimes writers will state the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion. You might be tempted to use this strategy if you don’t want to give everything away too early in your paper. You may think it would be more dramatic to keep the reader in the dark until the end and then “wow” them with your main idea, as in a Sherlock Holmes mystery. The reader, however, does not expect a mystery, but an analytical discussion of your topic in an academic style, with the main argument (thesis) stated up front. Example: (After a paper that lists numerous incidents from the book but never says what these incidents reveal about Douglass and his views on education): So, as the evidence above demonstrates, Douglass saw education as a way to undermine the slaveholders’ power and also an important step toward freedom.

- The “America the Beautiful”/”I Am Woman”/”We Shall Overcome” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion usually draws on emotion to make its appeal, but while this emotion and even sentimentality may be very heartfelt, it is usually out of character with the rest of an analytical paper. A more sophisticated commentary, rather than emotional praise, would be a more fitting tribute to the topic. Example: Because of the efforts of fine Americans like Frederick Douglass, countless others have seen the shining beacon of light that is education. His example was a torch that lit the way for others. Frederick Douglass was truly an American hero.

- The “Grab Bag” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion includes extra information that the writer found or thought of but couldn’t integrate into the main paper. You may find it hard to leave out details that you discovered after hours of research and thought, but adding random facts and bits of evidence at the end of an otherwise-well-organized essay can just create confusion. Example: In addition to being an educational pioneer, Frederick Douglass provides an interesting case study for masculinity in the American South. He also offers historians an interesting glimpse into slave resistance when he confronts Covey, the overseer. His relationships with female relatives reveal the importance of family in the slave community.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Douglass, Frederick. 1995. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. New York: Dover.

Hamilton College. n.d. “Conclusions.” Writing Center. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://www.hamilton.edu//academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/conclusions .

Holewa, Randa. 2004. “Strategies for Writing a Conclusion.” LEO: Literacy Education Online. Last updated February 19, 2004. https://leo.stcloudstate.edu/acadwrite/conclude.html.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Organizing Academic Research Papers: 9. The Conclusion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

The conclusion is intended to help the reader understand why your research should matter to them after they have finished reading the paper. A conclusion is not merely a summary of your points or a re-statement of your research problem but a synthesis of key points. For most essays, one well-developed paragraph is sufficient for a conclusion, although in some cases, a two-or-three paragraph conclusion may be required.

Importance of a Good Conclusion

A well-written conclusion provides you with several important opportunities to demonstrate your overall understanding of the research problem to the reader. These include:

- Presenting the last word on the issues you raised in your paper . Just as the introduction gives a first impression to your reader, the conclusion offers a chance to leave a lasting impression. Do this, for example, by highlighting key points in your analysis or findings.

- Summarizing your thoughts and conveying the larger implications of your study . The conclusion is an opportunity to succinctly answer the "so what?" question by placing the study within the context of past research about the topic you've investigated.

- Demonstrating the importance of your ideas . Don't be shy. The conclusion offers you a chance to elaborate on the significance of your findings.

- Introducing possible new or expanded ways of thinking about the research problem . This does not refer to introducing new information [which should be avoided], but to offer new insight and creative approaches for framing/contextualizing the research problem based on the results of your study.

Conclusions . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion . San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2018/07/conclusions_uwmadison_writingcenter_aug2012.pdf I. General Rules

When writing the conclusion to your paper, follow these general rules:

- State your conclusions in clear, simple language.

- Do not simply reiterate your results or the discussion.

- Indicate opportunities for future research, as long as you haven't already done so in the discussion section of your paper.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to restate the main argument . It reminds the reader of the strengths of your main argument(s) and reiterates the most important evidence supporting those argument(s). Make sure, however, that your conclusion is not simply a repetitive summary of the findings because this reduces the impact of the argument(s) you have developed in your essay.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or point of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If, prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from the data.

The conclusion also provides a place for you to persuasively and succinctly restate your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with all the information about the topic . Depending on the discipline you are writing in, the concluding paragraph may contain your reflections on the evidence presented, or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the research you have done will depend on the topic and whether your professor wants you to express your observations in this way.

NOTE : Don't delve into idle speculation. Being introspective means looking within yourself as an author to try and understand an issue more deeply not to guess at possible outcomes.

II. Developing a Compelling Conclusion

Strategies to help you move beyond merely summarizing the key points of your research paper may include any of the following.

- If your essay deals with a contemporary problem, warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend a specific course or courses of action.

- Cite a relevant quotation or expert opinion to lend authority to the conclusion you have reached [a good place to look is research from your literature review].

- Restate a key statistic, fact, or visual image to drive home the ultimate point of your paper.

- If your discipline encourages personal reflection, illustrate your concluding point with a relevant narrative drawn from your own life experiences.

- Return to an anecdote, an example, or a quotation that you introduced in your introduction, but add further insight that is derived from the findings of your study; use your interpretation of results to reframe it in new ways.

- Provide a "take-home" message in the form of a strong, succient statement that you want the reader to remember about your study.

III. Problems to Avoid Failure to be concise The conclusion section should be concise and to the point. Conclusions that are too long often have unnecessary detail. The conclusion section is not the place for details about your methodology or results. Although you should give a summary of what was learned from your research, this summary should be relatively brief, since the emphasis in the conclusion is on the implications, evaluations, insights, etc. that you make. Failure to comment on larger, more significant issues In the introduction, your task was to move from general [the field of study] to specific [your research problem]. However, in the conclusion, your task is to move from specific [your research problem] back to general [your field, i.e., how your research contributes new understanding or fills an important gap in the literature]. In other words, the conclusion is where you place your research within a larger context. Failure to reveal problems and negative results Negative aspects of the research process should never be ignored. Problems, drawbacks, and challenges encountered during your study should be included as a way of qualifying your overall conclusions. If you encountered negative results [findings that are validated outside the research context in which they were generated], you must report them in the results section of your paper. In the conclusion, use the negative results as an opportunity to explain how they provide information on which future research can be based. Failure to provide a clear summary of what was learned In order to be able to discuss how your research fits back into your field of study [and possibly the world at large], you need to summarize it briefly and directly. Often this element of your conclusion is only a few sentences long. Failure to match the objectives of your research Often research objectives change while the research is being carried out. This is not a problem unless you forget to go back and refine your original objectives in your introduction, as these changes emerge they must be documented so that they accurately reflect what you were trying to accomplish in your research [not what you thought you might accomplish when you began].

Resist the urge to apologize If you've immersed yourself in studying the research problem, you now know a good deal about it, perhaps even more than your professor! Nevertheless, by the time you have finished writing, you may be having some doubts about what you have produced. Repress those doubts! Don't undermine your authority by saying something like, "This is just one approach to examining this problem; there may be other, much better approaches...."

Concluding Paragraphs. College Writing Center at Meramec. St. Louis Community College; Conclusions . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions . The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Leibensperger, Summer. Draft Your Conclusion. Academic Center, the University of Houston-Victoria, 2003; Make Your Last Words Count . The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Tips for Writing a Good Conclusion . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion . San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Writing Conclusions . Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Writing: Considering Structure and Organization . Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Don't Belabor the Obvious!

Avoid phrases like "in conclusion...," "in summary...," or "in closing...." These phrases can be useful, even welcome, in oral presentations. But readers can see by the tell-tale section heading and number of pages remaining to read, when an essay is about to end. You'll irritate your readers if you belabor the obvious.

Another Writing Tip

New Insight, Not New Information!

Don't surprise the reader with new information in your Conclusion that was never referenced anywhere else in the paper. If you have new information to present, add it to the Discussion or other appropriate section of the paper. Note that, although no actual new information is introduced, the conclusion is where you offer your most "original" contributions in the paper; it's where you describe the value of your research, demonstrate your understanding of the material that you’ve presented, and locate your findings within the larger context of scholarship on the topic.

- << Previous: Limitations of the Study

- Next: Appendices >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 11:58 AM

- URL: https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803

- QuickSearch

- Library Catalog

- Databases A-Z

- Publication Finder

- Course Reserves

- Citation Linker

- Digital Commons

- Our Website

Research Support

- Ask a Librarian

- Appointments

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Research Guides

- Databases by Subject

- Citation Help

Using the Library

- Reserve a Group Study Room

- Renew Books

- Honors Study Rooms

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Policies

- Library Technology

User Information

- Grad Students

- Online Students

- COVID-19 Updates

- Staff Directory

- News & Announcements

- Library Newsletter

My Accounts

- Interlibrary Loan

- Staff Site Login

FIND US ON

- Conclusion to Research Process

Many of us have experienced research writing projects as a way to “prove” what we already believe. An essay assignment may ask us to take a position on a matter, and then support that position with evidence found in research. You will likely encounter projects like this in several classes in college.

Because you enter a project like this with a thesis in hand (you already know what you believe!), it is very tempting to look for and use only those sources that agree with you and to discard or overlook the others. If you are lucky, you find enough such sources and construct a paper. Ask yourself the following question, though: what have you found out or investigated during your research? Have you discovered new theories, opinions, or aspects of your subject? Did anything surprise you, intrigue you, or make you look further? If you answered no to these questions, you did not fulfill the purpose of true research, which is to explore, to discover, and to investigate.

So, should you begin every research project as a disinterested individual without opinions, ideas, and beliefs? Of course not! There is nothing wrong about having opinions, ideas, and beliefs about your subject before beginning the research process. Good researchers and writers are passionate about their work and want to share their passion with the world. Moreover, pre-existing knowledge can be a powerful research-starter. But what separates a true researcher from someone who simply looks for “proofs” for a pre-fabricated thesis is that a true researcher is willing to question those pre-existing beliefs and to take his or her understanding of the research topic well beyond what he or she knew at the outset. Speaking in terms of the process theory of writing, a good researcher and writer is willing to create new meaning, a new understanding of his or her subject through research and writing and based on the ideas and beliefs that he or she had entering the research project.

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of the mind as a galaxy. Authored by : Eddi van W.. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/7XaciB . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Research Writing as Process. Authored by : Pavel Zemliansky. Located at : https://threerivers.digication.com/mod/modchap2 . Project : Methods of Discovery. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Table of Contents

Instructor Resources (available upon sign-in)

- Overview of Instructor Resources

- Quiz Survey

Reading: Types of Reading Material

- Introduction to Reading

- Outcome: Types of Reading Material

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 1

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 2

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 3

- Characteristics of Texts, Conclusion

- Self Check: Types of Writing

Reading: Reading Strategies

- Outcome: Reading Strategies

- The Rhetorical Situation

- Academic Reading Strategies

- Self Check: Reading Strategies

Reading: Specialized Reading Strategies

- Outcome: Specialized Reading Strategies

- Online Reading Comprehension

- How to Read Effectively in Math

- How to Read Effectively in the Social Sciences

- How to Read Effectively in the Sciences

- 5 Step Approach for Reading Charts and Graphs

- Self Check: Specialized Reading Strategies

Reading: Vocabulary

- Outcome: Vocabulary

- Strategies to Improve Your Vocabulary

- Using Context Clues

- The Relationship Between Reading and Vocabulary

- Self Check: Vocabulary

Reading: Thesis

- Outcome: Thesis

- Locating and Evaluating Thesis Statements

- The Organizational Statement

- Self Check: Thesis

Reading: Supporting Claims

- Outcome: Supporting Claims

- Types of Support

- Supporting Claims

- Self Check: Supporting Claims

Reading: Logic and Structure

- Outcome: Logic and Structure

- Rhetorical Modes

- Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

- Diagramming and Evaluating Arguments

- Logical Fallacies

- Evaluating Appeals to Ethos, Logos, and Pathos

- Self Check: Logic and Structure

Reading: Summary Skills

- Outcome: Summary Skills

- How to Annotate

- Paraphrasing

- Quote Bombs

- Summary Writing

- Self Check: Summary Skills

- Conclusion to Reading

Writing Process: Topic Selection

- Introduction to Writing Process

- Outcome: Topic Selection

- Starting a Paper

- Choosing and Developing Topics

- Back to the Future of Topics

- Developing Your Topic

- Self Check: Topic Selection

Writing Process: Prewriting

- Outcome: Prewriting

- Prewriting Strategies for Diverse Learners

- Rhetorical Context

- Working Thesis Statements

- Self Check: Prewriting

Writing Process: Finding Evidence

- Outcome: Finding Evidence

- Using Personal Examples

- Performing Background Research

- Listening to Sources, Talking to Sources

- Self Check: Finding Evidence

Writing Process: Organizing

- Outcome: Organizing

- Moving Beyond the Five-Paragraph Theme

- Introduction to Argument

- The Three-Story Thesis

- Organically Structured Arguments

- Logic and Structure

- The Perfect Paragraph

- Introductions and Conclusions

- Self Check: Organizing

Writing Process: Drafting

- Outcome: Drafting

- From Outlining to Drafting

- Flash Drafts

- Self Check: Drafting

Writing Process: Revising

- Outcome: Revising

- Seeking Input from Others

- Responding to Input from Others

- The Art of Re-Seeing

- Higher Order Concerns

- Self Check: Revising

Writing Process: Proofreading

- Outcome: Proofreading

- Lower Order Concerns

- Proofreading Advice

- "Correctness" in Writing

- The Importance of Spelling

- Punctuation Concerns

- Self Check: Proofreading

- Conclusion to Writing Process

Research Process: Finding Sources

- Introduction to Research Process

- Outcome: Finding Sources

- The Research Process

- Finding Sources

- What are Scholarly Articles?

- Finding Scholarly Articles and Using Databases

- Database Searching

- Advanced Search Strategies

- Preliminary Research Strategies

- Reading and Using Scholarly Sources

- Self Check: Finding Sources

Research Process: Source Analysis

- Outcome: Source Analysis

- Evaluating Sources

- CRAAP Analysis

- Evaluating Websites

- Synthesizing Sources

- Self Check: Source Analysis

Research Process: Writing Ethically

- Outcome: Writing Ethically

- Academic Integrity

- Defining Plagiarism

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Using Sources in Your Writing

- Self Check: Writing Ethically

Research Process: MLA Documentation

- Introduction to MLA Documentation

- Outcome: MLA Documentation

- MLA Document Formatting

- MLA Works Cited

- Creating MLA Citations

- MLA In-Text Citations

- Self Check: MLA Documentation

Grammar: Nouns and Pronouns

- Introduction to Grammar

- Outcome: Nouns and Pronouns

- Pronoun Cases and Types

- Pronoun Antecedents

- Try It: Nouns and Pronouns

- Self Check: Nouns and Pronouns

Grammar: Verbs

- Outcome: Verbs

- Verb Tenses and Agreement

- Non-Finite Verbs

- Complex Verb Tenses

- Try It: Verbs

- Self Check: Verbs

Grammar: Other Parts of Speech

- Outcome: Other Parts of Speech

- Comparing Adjectives and Adverbs

- Adjectives and Adverbs

- Conjunctions

- Prepositions

- Try It: Other Parts of Speech

- Self Check: Other Parts of Speech

Grammar: Punctuation

- Outcome: Punctuation

- End Punctuation

- Hyphens and Dashes

- Apostrophes and Quotation Marks

- Brackets, Parentheses, and Ellipses

- Semicolons and Colons

- Try It: Punctuation

- Self Check: Punctuation

Grammar: Sentence Structure

- Outcome: Sentence Structure

- Parts of a Sentence

- Common Sentence Structures

- Run-on Sentences

- Sentence Fragments

- Parallel Structure

- Try It: Sentence Structure

- Self Check: Sentence Structure

Grammar: Voice

- Outcome: Voice

- Active and Passive Voice

- Using the Passive Voice

- Conclusion to Grammar

- Try It: Voice

- Self Check: Voice

Success Skills

- Introduction to Success Skills

- Habits for Success

- Critical Thinking

- Time Management

- Writing in College

- Computer-Based Writing

- Conclusion to Success Skills

OASIS: Writing Center

Writing a paper: conclusions, writing a conclusion.

A conclusion is an important part of the paper; it provides closure for the reader while reminding the reader of the contents and importance of the paper. It accomplishes this by stepping back from the specifics in order to view the bigger picture of the document. In other words, it is reminding the reader of the main argument. For most course papers, it is usually one paragraph that simply and succinctly restates the main ideas and arguments, pulling everything together to help clarify the thesis of the paper. A conclusion does not introduce new ideas; instead, it should clarify the intent and importance of the paper. It can also suggest possible future research on the topic.

An Easy Checklist for Writing a Conclusion

It is important to remind the reader of the thesis of the paper so he is reminded of the argument and solutions you proposed.

Think of the main points as puzzle pieces, and the conclusion is where they all fit together to create a bigger picture. The reader should walk away with the bigger picture in mind.

Make sure that the paper places its findings in the context of real social change.

Make sure the reader has a distinct sense that the paper has come to an end. It is important to not leave the reader hanging. (You don’t want her to have flip-the-page syndrome, where the reader turns the page, expecting the paper to continue. The paper should naturally come to an end.)

No new ideas should be introduced in the conclusion. It is simply a review of the material that is already present in the paper. The only new idea would be the suggesting of a direction for future research.

Conclusion Example

As addressed in my analysis of recent research, the advantages of a later starting time for high school students significantly outweigh the disadvantages. A later starting time would allow teens more time to sleep--something that is important for their physical and mental health--and ultimately improve their academic performance and behavior. The added transportation costs that result from this change can be absorbed through energy savings. The beneficial effects on the students’ academic performance and behavior validate this decision, but its effect on student motivation is still unknown. I would encourage an in-depth look at the reactions of students to such a change. This sort of study would help determine the actual effects of a later start time on the time management and sleep habits of students.

Related Webinar

Didn't find what you need? Search our website or email us .

Read our website accessibility and accommodation statement .

- Previous Page: Thesis Statements

- Next Page: Writer's Block

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.6: Conclusion to Research Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 5298

- Lumen Learning

Many of us have experienced research writing projects as a way to “prove” what we already believe. An essay assignment may ask us to take a position on a matter, and then support that position with evidence found in research. You will likely encounter projects like this in several classes in college.

Because you enter a project like this with a thesis in hand (you already know what you believe!), it is very tempting to look for and use only those sources that agree with you and to discard or overlook the others. If you are lucky, you find enough such sources and construct a paper. Ask yourself the following question, though: what have you found out or investigated during your research? Have you discovered new theories, opinions, or aspects of your subject? Did anything surprise you, intrigue you, or make you look further? If you answered no to these questions, you did not fulfill the purpose of true research, which is to explore, to discover, and to investigate.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The purpose of research is not to look for proofs that would fit the author’s pre-existing theories, but to learn about the subject of the investigation as much as possible and then form those theories, opinions, and arguments on the basis of this newly found knowledge and understanding. And what if there is no data that prove your theory? What if, after hours and days of searching, you realize that there is nothing out there that would allow you to make the claim that you wanted to make? Most likely, this will lead to frustration, a change of the paper’s topic, and having to start all over again.

So, should you begin every research project as a disinterested individual without opinions, ideas, and beliefs? Of course not! There is nothing wrong about having opinions, ideas, and beliefs about your subject before beginning the research process. Good researchers and writers are passionate about their work and want to share their passion with the world. Moreover, pre-existing knowledge can be a powerful research-starter. But what separates a true researcher from someone who simply looks for “proofs” for a pre-fabricated thesis is that a true researcher is willing to question those pre-existing beliefs and to take his or her understanding of the research topic well beyond what he or she knew at the outset. Speaking in terms of the process theory of writing, a good researcher and writer is willing to create new meaning, a new understanding of his or her subject through research and writing and based on the ideas and beliefs that he or she had entering the research project.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

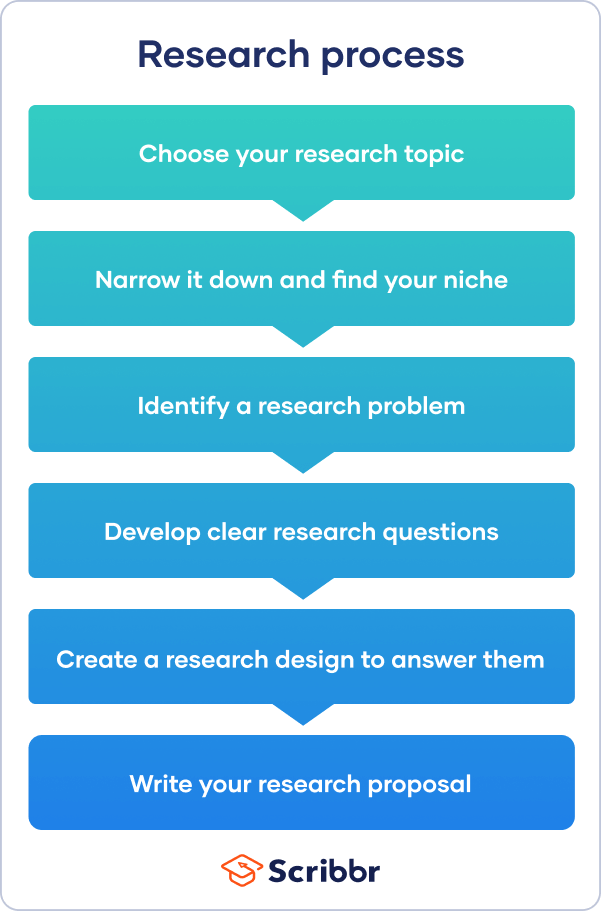

Research Process Steps: What they are + How To Follow

There are various approaches to conducting basic and applied research. This article explains the research process steps you should know. Whether you are doing basic research or applied research, there are many ways of doing it. In some ways, each research study is unique since it is conducted at a different time and place.

Conducting research might be difficult, but there are clear processes to follow. The research process starts with a broad idea for a topic. This article will assist you through the research process steps, helping you focus and develop your topic.

Research Process Steps

The research process consists of a series of systematic procedures that a researcher must go through in order to generate knowledge that will be considered valuable by the project and focus on the relevant topic.

To conduct effective research, you must understand the research process steps and follow them. Here are a few steps in the research process to make it easier for you:

Step 1: Identify the Problem

Finding an issue or formulating a research question is the first step. A well-defined research problem will guide the researcher through all stages of the research process, from setting objectives to choosing a technique. There are a number of approaches to get insight into a topic and gain a better understanding of it. Such as:

- A preliminary survey

- Case studies

- Interviews with a small group of people

- Observational survey

Step 2: Evaluate the Literature

A thorough examination of the relevant studies is essential to the research process . It enables the researcher to identify the precise aspects of the problem. Once a problem has been found, the investigator or researcher needs to find out more about it.

This stage gives problem-zone background. It teaches the investigator about previous research, how they were conducted, and its conclusions. The researcher can build consistency between his work and others through a literature review. Such a review exposes the researcher to a more significant body of knowledge and helps him follow the research process efficiently.

Step 3: Create Hypotheses

Formulating an original hypothesis is the next logical step after narrowing down the research topic and defining it. A belief solves logical relationships between variables. In order to establish a hypothesis, a researcher must have a certain amount of expertise in the field.

It is important for researchers to keep in mind while formulating a hypothesis that it must be based on the research topic. Researchers are able to concentrate their efforts and stay committed to their objectives when they develop theories to guide their work.

Step 4: The Research Design

Research design is the plan for achieving objectives and answering research questions. It outlines how to get the relevant information. Its goal is to design research to test hypotheses, address the research questions, and provide decision-making insights.

The research design aims to minimize the time, money, and effort required to acquire meaningful evidence. This plan fits into four categories:

- Exploration and Surveys

- Data Analysis

- Observation

Step 5: Describe Population

Research projects usually look at a specific group of people, facilities, or how technology is used in the business. In research, the term population refers to this study group. The research topic and purpose help determine the study group.

Suppose a researcher wishes to investigate a certain group of people in the community. In that case, the research could target a specific age group, males or females, a geographic location, or an ethnic group. A final step in a study’s design is to specify its sample or population so that the results may be generalized.

Step 6: Data Collection

Data collection is important in obtaining the knowledge or information required to answer the research issue. Every research collected data, either from the literature or the people being studied. Data must be collected from the two categories of researchers. These sources may provide primary data.

- Questionnaire

Secondary data categories are:

- Literature survey

- Official, unofficial reports

- An approach based on library resources