How to Write an Evidence-Based Practice Paper in Nursing

Some call it an EBP paper while some evidence-based research paper, and it comes in many other forms as well, including EBP case reports, EBP capstone projects, EBP coursework, or EBP thesis. Regardless of the name, without explicit knowledge on how to write an evidence-based practice paper, you cannot wrap your mind around it. Evidence-based papers are written by students so that they can develop confidence, research interests, critical thinking, creativity, and decision-making skills that are applicable in real-world clinical settings.

Any nursing school student must write an evidence-based practice paper. In most cases, EBP papers can come in the form of change management papers where quality improvement processes are recommended. To avoid making blunders when writing, it is vital to grasp the entire writing process.

Unlike other nursing papers and essays, evidence-based practice papers require in-depth reasoning, research, and reading. We acknowledge that writing a great evidence-based paper that is gradable takes sweat and is very challenging.

We have compiled this guideline for writing an evidence-based nursing paper to ease the burden on your side. If you quite can't find it easy even after reading this article, we have experienced nursing paper writers who can always help you.

We are the best nursing paper writing service; we do this to help you take care of your wellbeing, achieve freedom, and extend your time caring for others in your clinical. Let us dig right into it, won't we?

What is Evidence-Based Practice?

Evidence-Based Practice in the field of nursing focuses on the premise that medical practice should focus on adapted and developed principles through a cycle of evidence, research, and analysis of theory. Evidence-based practice intends to address the changes in practice based on the nursing and non-nursing theories developed through proper research.

In nursing, the implementation of EBP comes in the form of a systematic review, where research is reviewed based on a particular guideline to determine its suitability for being used as a gold standard in practice.

The systematic review helps in sense-making from the mammoth of information available for effective change management, implementation, and institutionalization.

The EBP process involves six significant steps:

- Assessment of the need for change : This entails the formulation of a research question or hypothesis based on the gaps in current practice.

- Location of the best evidence : Depending on the levels of nursing resources or evidence, the next step entails assessing the credibility, reliability, and relevance of the evidence or peer-reviewed articles.

- Synthesis of evidence : This step involves the comparison and contrast of available sources of evidence to establish similarities and differences to determine the best course of approach.

- Designing change : through the results of the synthesis of the available evidence, the next step is to create an effective change based on the evidence collected. It also involves drafting the change implementation plan within the clinical setting.

- Implementing and Evaluating Change : After the design comes to the process of initiating the change through change advocates such as nurse leaders and nurses themselves, it is the phase where the new process is established into practice. Various change management theories can be followed to ensure the fruition of the change management plan.

- Integration and Sustaining Change : Once the new evidence has been used to implement change, it is adopted through policy or guidelines within the clinical settings. It also entails the process of continuous improvement to achieve the best.

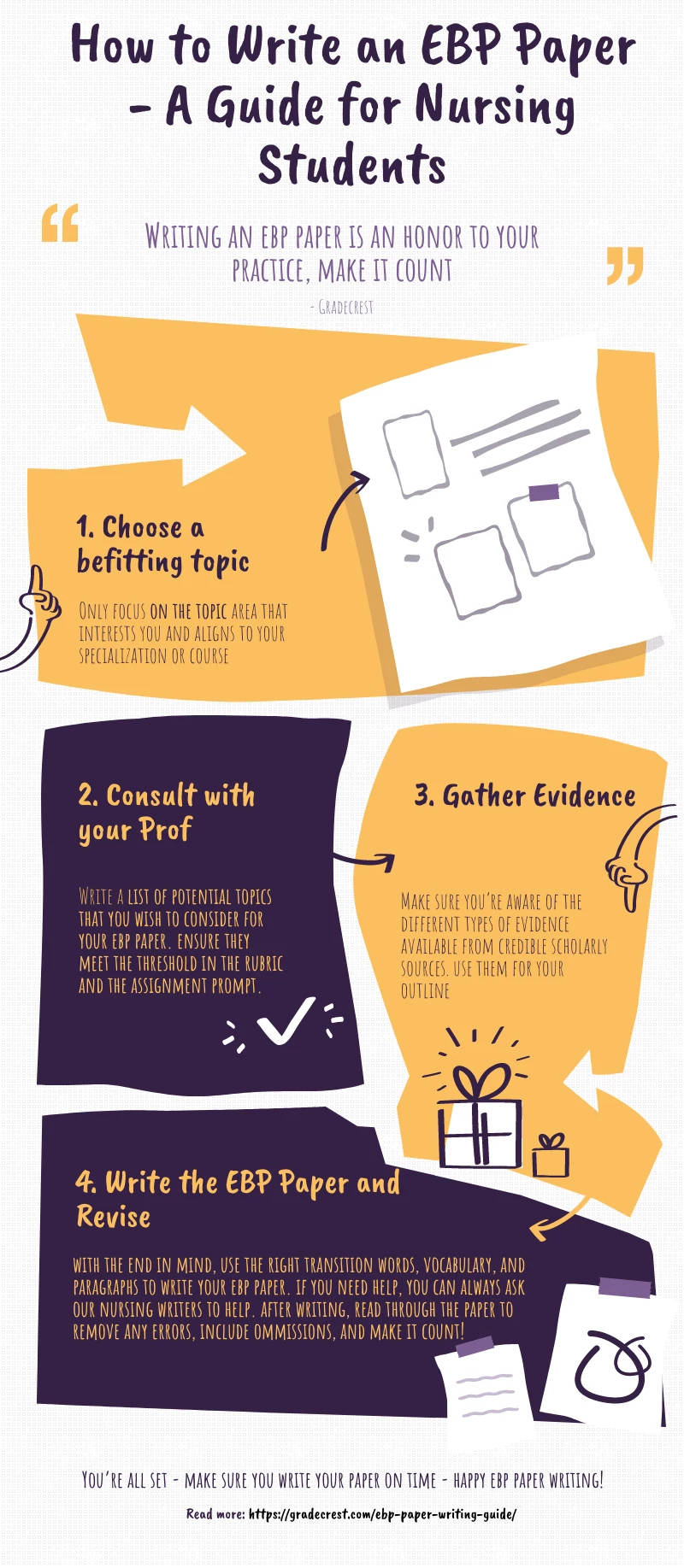

Steps of Writing an EBP Research Paper in Nursing

Once you have been assigned to write an evidence-based paper, you need to follow the steps below to write the best essay.

1. Choose a Topic for your Paper

There are many methods you can use when choosing an EBP topic. You can get ideas from your coursework, peer-reviewed sources, class assignments, and past evidence-based projects done. Thanks to the Internet, there are various evidence-based practice topic ideas. However, choose a topic that resonates well with your passion and interest in nursing practice. For instance, if you are looking forward to improving patient flow in the ED using technology, be sure that you are cognizant of such technology as EHR or HIT. Begin by exploring the assignment and make some notes; you should then settle for a tentative topic.

2. Consult with your Professor/Instructor

Nursing education, just like nursing practice, calls for collaboration and getting feedback. Therefore, once you have selected a creative, evidence-based practice topic , you must make an appointment with either the writing center or the professor/instructor for confirmation. In some instances, your professor/instructor will request for an evidence-based practice proposal. In the EBP proposal, you must state the nursing issue you intend to solve, the change management process, and the rationale for the change. If it is convincing enough, you will get a go-ahead. Otherwise, you will need to revise the EBP nursing proposal.

Tip: SELECT a good health indicator (disease, health conditions, working/living conditions) , DESCRIBE the population or sub-population of the target, find EVIDENCE of around 7-10 peer-reviewed sources that support your proposal, and DESCRIBE the intended outcomes and rationale of the change proposed in the clinical setting.

Some of the health indicators you can use for your EBP paper include socio-economic status; gender, education, environment, employment, genetic endowment, culture, child development, healthcare services, access, quality, cost of care, social support, coping skills, etc.

The EBP papers can include a change model, population health model, nursing theory, and nursing interventions and each must be justified using credible evidence.

3. Gathering Supporting Evidence - Research

The backbone of an evidence-based paper is evidence. Therefore, you need to extensively research both online and print sources to get facts to support your EBP paper thesis statement. Once you have developed the problem statement and outlined the thesis statement, you should critically evaluate the sources to determine those that support the thesis.

In some instances, the instructor might request you to write an annotated bibliography or critically analyze each of the articles or the main article that supports your evidence-based practice paper. A common approach is through using an evidence evaluation table. When selecting the sources, remember that there are both primary and secondary sources.

You can get primary and secondary sources from databases such as PubMed, EBSCO, UpToDate, TRIP Database, OVID, The Cochrane Collaboration, and CINAHL. Besides, you can depend on .gov, .org, and .edu websites to get information. Professional and government organizations, as well as NGOs, can be a starting point of research. They are an excellent resource for statistics, epidemiology data, and further information. Excellent research means that the research question, hypothesis, and thesis statement will be supported and answered.

Related: How to write a great thesis statement for any paper.

Deciding on the Best Resources for EBP Papers

There are primary and secondary data sources when it comes to scientific writing. Instead of collecting and analyzing real data as students do for qualitative and quantitative or mixed methods thesis, dissertation, and research papers, an EBP paper is purely based on the published findings from primary research. It is imperative, therefore, that a nursing student only uses credible, valid, and reliable sources. Here are three criteria to select a good source for your EBP paper:

- A research journal article is only reliable if published in a reliable database/journal and is peer-reviewed. It depends on the level of the evidence as well. Will the same test yield similar results if replicated?

- A valid research study has followed the strict research protocols, is up to date, and is relevant to the chosen EBP paper topic selected. Does the study measure what it says it intends to measure?

- Credible research that can be incorporated into an EBP paper must have verifiable findings, published in a reputable journal, and is scholarly. Is the research study from a reputable journal?

- Is the research report, article, or journal primary research such as qualitative research, quantitative research, randomized controlled trial, controlled case studies, or quasi-experimental study?

It is only natural that you can dislike the entire process of writing an EBP paper, not because you don't know how to, but probably because of the strict and laborious process. If this is the case, our nursing writing service is all you need for your peace of mind. We have experienced nursing assignment help experts who can craft the best papers for you. Stop, think about it, and let us know if you need some help.

Related reading: How to title an article in an academic paper.

Outline of an Evidence-Based Practice Paper

A good evidence-based paper in nursing must have several parts, each of which are completed with precision, care, and wit. If you have researched online for evidence-based practice paper examples , you will agree with us that the format or structure is more or less as broken down below. It is the same structure you will see on an evidence-based practice paper template that you will likely receive from class. Here is a critical breakdown of what to include in your nursing evidence-based practice paper:

1. Title of the EBP Paper

A good title will either attract and keep or turn off your audience, instructor/professor. Therefore, having an excellent title for your evidence-based practice case study, report, write-up, or research paper is paramount. The title aims to set the scope of the EBP paper and provide a hint about the hypothesis or thesis statement. It is, therefore, imperative that it is concise, clear, and fine-tuned. If you decide to write the title as a question, you could paraphrase the PICOT statement, for example. Otherwise, it can also take forms such as statements or facts opposing the status quo. Whichever direction you choose to align to, the aim remains constant to give more insight to the reader from the onset.

2. Thesis Statement

While the PICOT statement can already tell what your entire EBP paper is all about, you need to develop a great thesis statement. A thesis statement, usually the last sentence or two, is like a blueprint of the entire paper. It is the foundation upon which the whole paper is built. Take note that a thesis is not a hypothesis, which is an idea that you either want to prove or refute based on a set of available evidence. An evidence-based practice paper with a thesis ultimately earns the best grade without leaving the reader to look for it the entire paper.

The thesis statement must be specific, manageable, and enjoyable. A sample EBP thesis statement can be: According to new developments in genomics and biotechnology, stem cells have reportedly been used in breast cancer treatment with higher chances of remission in the patients. Novel approaches to pain management dictate that a nurse must obtain three kinds of knowledge to respond effectively to patients' pain: knowledge of self, knowledge of standards of care, and knowledge of pain.

A thesis can also be an implied argument, which makes it descriptive. However, not so many professors like such. This paper discusses

3. Introduction

The introduction of evidence-based practice must reflect certain elements. First, you must present a background to the research question or nursing issue. It would help if you also painted a clear picture of the problem through a thorough and brief problem statement and at the same time, provide the rationale. You can organize your intro into a PICO:

Patient/Problem : What problems does the patient group have? What needs to be solved?

Intervention : What intervention is being considered or evaluated? Cite appropriate literature.

Comparison : What other interventions are possible? Cite appropriate literature.

Outcome : What is the intended outcome of the research question?

The thesis statement we have discussed above then comes in as either a sentence or two in the last part of the introduction. The research problem should help generate the research question or hypothesis for the entire EBP paper.

4. Methodology

As indicated before, an EBP research paper does not focus on research; instead, it focuses on a body of knowledge or evidence. For that matter, when writing an EBP paper, you only collect data from literature produced on your chosen topic. A confusing bit when researching evidence to use is deciding on what level of evidence to use. There are systematic reviews, literature reviews, white papers, opinion papers, practice papers, peer-reviewed journals, critically appraised topics, RCTs, Case-controlled studies, or cohort studies, you name it. You must decide which level of evidence is appropriate. It trickles down to the scholarly source's validity, reliability, and credibility. Your methodology should include:

- The databases you searched, the search terms, the total articles yielded per search, the inclusion and selection criteria, the exclusion criteria.

- You should indicate the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the articles and the number of articles you finally end up with.

You can further choose to use knowledge as evidence based on authority, a priori, theory, and tenacity, as advised by Fawcett and Garity in their book Evaluating research for evidence-based nursing practice.

5. EBP Literature Review

In the literature review section, you aim to explore the associations of the evidence chosen given your topic. It aims at either finding the gap in those studies or using the knowledge to build on the topic. For instance, if you are to come up with a new management approach for pressure ulcers in palliative care, choose credible evidence on the topic. Find the effectiveness of your proposed approach in other environments, what works well, and what precautions should be taken. It is more of comparing and contrasting the sources. You also ought to be critical as it is the only way you can develop the best EBP paper. It is here that you report your findings from the literature. You can do it in the form of a table outlining the aspects of each study including demographics, samples, methodology, and level of evidence, results, and limitations.

6. Discussion

Like any other professional research setting, the discussion section often discusses the changed practice, implementation approach, and evaluation strategies. This can be your approach as well in your EBP paper. However, go further to explore how the findings led to a given change in practice, the efficiency after that, and suggest the best strategy for implementing the change in your chosen organization. Make comparisons if necessary.

7. Conclusion

In your conclusion, you should wind up the paper, summarize the EBP paper, and leave the readers satisfied. Your revamped thesis statement can feature in the conclusion. Make your conclusion count.

Finally, your EBP paper must have references, works cited, or a bibliography section. You realize that most EBP papers are written in either APA formatting or Harvard formatting .

Furthermore, it would be best if you wrote your abstract section last, which is about 150-250 words. It aims to offer a highlight of the entire evidence-based paper.

Here is a graphic/visual representation of the entire EBP writing process for students.

You can Buy Evidence-Based Papers in Nursing Here!

If your worry was how to write an evidence-based practice paper in nursing at the beginning, it is possible that you feel like a pro to this end. It is a super feeling that every reader who interacted with our article on how to write nursing care plans had, and they suggested we do this article as well.

As the best nursing assignment help service , we gave in to the pressure and put our best feet forward. We intend to create a resource for nursing students and learners. We also have expert writers to help in various academic fields. If you feel stuck with anything, do not hesitate to ask for help.

You can get a sample EBP research paper to benchmark on as you complete your nursing evidence-based research paper. Apart from the EBP research paper examples online, we offer you the chance to have a custom sample that matches your instructions.

In this article, we have answered the question: what is EBP? What is an EBP research paper? and how to write an APA evidence-based research paper in nursing.

If you are far ahead in your nursing level, our article on nursing capstone ideas can also be an excellent place to sojourn and drink from the fountain of wisdom. The students who have sourced examples of evidence-based practice assignments from us have ended up mastering concepts. Do not just wait, be part of the excelling team!

Gradecrest is a professional writing service that provides original model papers. We offer personalized services along with research materials for assistance purposes only. All the materials from our website should be used with proper references. See our Terms of Use Page for proper details.

What is Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing? (With Examples, Benefits, & Challenges)

Are you a nurse looking for ways to increase patient satisfaction, improve patient outcomes, and impact the profession? Have you found yourself caught between traditional nursing approaches and new patient care practices? Although evidence-based practices have been used for years, this concept is the focus of patient care today more than ever. Perhaps you are wondering, “What is evidence-based practice in nursing?” In this article, I will share information to help you begin understanding evidence-based practice in nursing + 10 examples about how to implement EBP.

What Is Evidence-Based Practice In Nursing?

When was evidence-based practice first introduced in nursing, who introduced evidence-based practice in nursing, what is the difference between evidence-based practice in nursing and research in nursing, what are the benefits of evidence-based practice in nursing, top 5 benefits to the patient, top 5 benefits to the nurse, top 5 benefits to the healthcare organization, 10 strategies nursing schools employ to teach evidence-based practices, 1. assigning case studies:, 2. journal clubs:, 3. clinical presentations:, 4. quizzes:, 5. on-campus laboratory intensives:, 6. creating small work groups:, 7. interactive lectures:, 8. teaching research methods:, 9. requiring collaboration with a clinical preceptor:, 10. research papers:, what are the 5 main skills required for evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. critical thinking:, 2. scientific mindset:, 3. effective written and verbal communication:, 4. ability to identify knowledge gaps:, 5. ability to integrate findings into practice relevant to the patient’s problem:, what are 5 main components of evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. clinical expertise:, 2. management of patient values, circumstances, and wants when deciding to utilize evidence for patient care:, 3. practice management:, 4. decision-making:, 5. integration of best available evidence:, what are some examples of evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. elevating the head of a patient’s bed between 30 and 45 degrees, 2. implementing measures to reduce impaired skin integrity, 3. implementing techniques to improve infection control practices, 4. administering oxygen to a client with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (copd), 5. avoiding frequently scheduled ventilator circuit changes, 6. updating methods for bathing inpatient bedbound clients, 7. performing appropriate patient assessments before and after administering medication, 8. restricting the use of urinary catheterizations, when possible, 9. encouraging well-balanced diets as soon as possible for children with gastrointestinal symptoms, 10. implementing and educating patients about safety measures at home and in healthcare facilities, how to use evidence-based knowledge in nursing practice, step #1: assessing the patient and developing clinical questions:, step #2: finding relevant evidence to answer the clinical question:, step #3: acquire evidence and validate its relevance to the patient’s specific situation:, step #4: appraise the quality of evidence and decide whether to apply the evidence:, step #5: apply the evidence to patient care:, step #6: evaluating effectiveness of the plan:, 10 major challenges nurses face in the implementation of evidence-based practice, 1. not understanding the importance of the impact of evidence-based practice in nursing:, 2. fear of not being accepted:, 3. negative attitudes about research and evidence-based practice in nursing and its impact on patient outcomes:, 4. lack of knowledge on how to carry out research:, 5. resource constraints within a healthcare organization:, 6. work overload:, 7. inaccurate or incomplete research findings:, 8. patient demands do not align with evidence-based practices in nursing:, 9. lack of internet access while in the clinical setting:, 10. some nursing supervisors/managers may not support the concept of evidence-based nursing practices:, 12 ways nurse leaders can promote evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. be open-minded when nurses on your teams make suggestions., 2. mentor other nurses., 3. support and promote opportunities for educational growth., 4. ask for increased resources., 5. be research-oriented., 6. think of ways to make your work environment research-friendly., 7. promote ebp competency by offering strategy sessions with staff., 8. stay up-to-date about healthcare issues and research., 9. actively use information to demonstrate ebp within your team., 10. create opportunities to reinforce skills., 11. develop templates or other written tools that support evidence-based decision-making., 12. review evidence for its relevance to your organization., bonus 8 top suggestions from a nurse to improve your evidence-based practices in nursing, 1. subscribe to nursing journals., 2. offer to be involved with research studies., 3. be intentional about learning., 4. find a mentor., 5. ask questions, 6. attend nursing workshops and conferences., 7. join professional nursing organizations., 8. be honest with yourself about your ability to independently implement evidence-based practice in nursing., useful resources to stay up to date with evidence-based practices in nursing, professional organizations & associations, blogs/websites, youtube videos, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered by our expert, 1. what did nurses do before evidence-based practice, 2. how did florence nightingale use evidence-based practice, 3. what is the main limitation of evidence-based practice in nursing, 4. what are the common misconceptions about evidence-based practice in nursing, 5. are all types of nurses required to use evidence-based knowledge in their nursing practice, 6. will lack of evidence-based knowledge impact my nursing career, 7. i do not have access to research databases, how do i improve my evidence-based practice in nursing, 7. are there different levels of evidence-based practices in nursing.

• Level One: Meta-analysis of random clinical trials and experimental studies • Level Two: Quasi-experimental studies- These are focused studies used to evaluate interventions. • Level Three: Non-experimental or qualitative studies. • Level Four: Opinions of nationally recognized experts based on research. • Level Five: Opinions of individual experts based on non-research evidence such as literature reviews, case studies, organizational experiences, and personal experiences.

8. How Can I Assess My Evidence-Based Knowledge In Nursing Practice?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction to Evidence-Based Practice

How to use this tutorial.

This tutorial is organized into a number of chapters. Each chapter has accompanying case studies and activities to check your knowledge. We suggest following the pages in order until you arrive at a Case Studies page, and then follow your appropriate Case Study link.

To navigate, you can either:

Evidence-Based Practice Copyright © by Various Authors - See Each Chapter Attribution is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Evidence-Based Practice

What is evidence-based practice, the process of evidence-based practice.

- PICO(T) for Clinical Questions

- Qualitative Questions This link opens in a new window

- 3. Appraise

- Study Design

- Resources about EBP

Your Health Sciences Librarian

Creative Commons License

Evidence-Based Practice (or Evidence-Based Medicine) is, "the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research." (Sackett et al., 1996)

"Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) isn’t about developing new knowledge or validating existing knowledge. It’s about translating the evidence and applying it to clinical decision-making. The purpose of EBP is to use the best evidence available to make patient-care decisions. Most of the best evidence stems from research. But EBP goes beyond research use and includes clinical expertise as well as patient preferences and values. The use of EBP takes into consideration that sometimes the best evidence is that of opinion leaders and experts, even though no definitive knowledge from research results exists." (Conner, 2014)

The Evidence-Based Practice process has five steps. The process begins with the patient's situation and proceeds to asking an answerable question, finding and getting the evidence, evaluating the evidence and then applying the information to the patient's situation. Lastly, perform a reflective review of the process and consider areas for improvement.

ASK

acquire , appraise , apply , assess.

- Next: 1. Ask >>

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 11:48 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.gonzaga.edu/EBP

Eugene McDermott Library

Evidence-based practice (ebp), introduction.

- Ask a Question

- Acquire the Evidence - Strategy

- Acquire the Evidence - Tools

- Appraise the Evidence

- Apply & Act

- Streaming Media

- Additional Resources

Subject Guide

About This Guide

The purpose of this guide is to define the subject of Evidence-Based Practice and to inform students, faculty, and our community of the many types of resources available to explore this topic.

While the concepts of evidence-based practice (EBP) are now commonly embraced in fields such as education, law and management, much of it emerged in medicine. Accordingly, most of the examples and resources suggested in this guide are based on clinical research.

Use the tabs to learn more about the five-step Evidence-Based Practice cycle and navigate to further reading.

"Evidence based practice (EBP) is the integration of clinical expertise, patient values, and the best evidence into the decision making process for patient care."

Sackett, D.L., et al. (2000). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

In contrast with a reliance on history or traditional solutions, EBP is the combination of existing clinical knowledge, consideration of the patient's needs and choices, and the most up-to-date and credible scientific research available. In an evidence-based approach, the clinician will begin by forming answerable questions about diagnosis, treatment, harm / etiology, prognosis or prevention with the patient's specific needs factored in. A research path is then chosen depending on the question type. The clinician (and often, a medical librarian) will gather information from the appropriate types of studies based on the strength and precision of their research methodology (more on the next page). The research is appraised for quality and relevance and then implemented based on each unique scenario. EBP also includes evaluation of the efficacy of the implemented clinical decision.

Adoption of evidence-based practices can be found across many disciplines in the sciences, medicine and academia. Here are just a few of the statements you'll find among professional associations:

- The National Council of State Boards of Nursing's Evidence-based Regulation of Nursing Education page and position statement .

- The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association's Evidence-Based Practice in Communication Disorders [Position Statement]

- The American Psychological Association's Policy Statement on Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology

The EBP Cycle

There are 5 steps in the EBP cycle:

Construct an answerable clinical question derived from the patient dilemma

Systematically retrieve the best available research

Critically appraise the validity and applicability of the evidence

Integrate evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and apply to practice

Evaluate the performance and success of the change in practice. Ask new questions...

This guide focuses on the first three steps in the cycle: developing a searchable question, finding the evidence and appraising the quality of the evidence.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this guide's content were reused with kind permission from Curtin University Library.

- Next: Ask a Question >>

- Last Updated: Feb 3, 2024 1:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.utdallas.edu/evidence-based-practice

Evidence-Based Practice in Health

Introduction: about this guide, what is evidence-based practice.

- PICO Framework and the Question Statement

- Types of Clinical Question

- Hierarchy of Evidence

- Selecting a Resource

- Searching PubMed

- Module 3: Appraise

- Module 4: Apply

- Module 5: Audit

- Reference Shelf

How to cite this Guide:

Turner, M. (2014). "Evidence-Based Practice in Health.” Retrieved from University of Canberra website: https://canberra.libguides.com/evidence

Read more about Evidence-Based Medicine

Supporting your practice: Evidence-Based Medicine. By Dr Mary Bushell MPS . 6 Read this article and you should be able to:

- Define Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM)

- Explain different study designs and the level of evidence they generate

- Explain the significance of probability (p) values, confidence intervals (CI), relative risk (RR), odds ratios (OR), hazard ratios (HR), and number-needed-to-treat (NNT)

- Discuss the importance of EBM for healthcare professionals.

This guide includes a tutorial about Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) in Health, a Reference Shelf of supporting eBooks, and a Toolkit of online sources of evidence.

The goals of the tutorial are to clearly outline the theory of EBP and to explain how that theory can be put to practice in the day-to-day work of caring for patients. The tutorial includes an introduction and modules that follow the "5A's Cycle" of EBP that include assessing the patient and prioritizing questions about his/her care, asking a focused clinical question, acquiring the evidence to answer the question, appraising the research, applying the research findings to patient care, and finally auditing your performance.. The cycle begins again with an assessment of the patient and the patient's care. 1

The tutorial focuses largely on efficient literature searching and therefore on asking questions and acquiring the best evidence. In particular, it suggests specific strategies for finding evidence from primary studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses using EBP tools. Appraisal is also touched upon, with suggestions for scanning search results to identify articles more likely to yield robust, applicable evidence.

At the end of the tutorial, you should be able to:

- Formulate a clinical question using the PICO framework;

- Identify five common categories of clinical questions;

- Identify which research methodologies provide the best evidence for your question type;

- Distinguish between systematic reviews, meta-analyses and narrative or clinical topic reviews;

- Search Medline/PubMed effectively for studies likely to provide the current best evidence by

- Identifying appropriate search terms, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms; and

- Employ evidence filters such as PubMed's Clinical Queries;

- Identify articles from your PubMed search results that are most likely to provide current, valid, reliable and relevant evidence to answer your question.

This tutorial assumes you already have some familiarity with basic and advanced PubMed search techniques, as well as with MeSH searching.

There are many excellent on-line and print guides that address the critical appraisal of a research report and the application of evidence to an individual patient's care. You will find links to selected resources that provide especially rich content in these areas in the Appraise and Apply modules of this tutorial.

It is best to work systematically through the various modules, starting with Introduction: About Evidence-Based Practice, and then the five modules.

Reference Shelf of EBP eBooks and Books

The Library has a vast range of books and ebooks about EBP that can be found via Library Search (the Library Catalogue). The Reference Shelf in this guide lists a range of the EBP eBooks and Books by category and discipline area.

What is Evidence-Based Practice?

The classic definition of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is from Dr David Sackett. EBP is “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research”. 2

EBP has developed over time to now integrate the best research evidence, clinical expertise, the patient's individual values and circumstances, and the characteristics of the practice in which the health professional works. 3

So, EBP is not only about applying the best research evidence to your decision-making, but also using the experience, skills and training that you have as a health professional and taking into account the patient's situation and values (e.g. social support, financial situation), as well as the practice context (e.g. limited funding) in which you are working. The process of integrating all of this information is known as clinical reasoning. When you consider all of these four elements in a way that allows you to make decisions about the care of a patient, you are engaging in EBP. 4

Why is Evidence-Based Practice Important?

EBP is important because it aims to provide the most effective care that is available, with the aim of improving patient outcomes. Patients expect to receive the most effective care based on the best available evidence. EBP promotes an attitude of inquiry in health professionals and starts us thinking about: Why am I doing this in this way? Is there evidence that can guide me to do this in a more effective way? As health professionals, part of providing a professional service is ensuring that our practice is informed by the best available evidence. EBP also plays a role in ensuring that finite health resources are used wisely and that relevant evidence is considered when decisions are made about funding health services. 4

What happened before Evidence-Based Practice?

Before EBP health professionals relied on the advice of more experienced colleagues, often taken at face value, their intuition, and on what they were taught as students. Experience is subject to flaws of bias and what we learn as students can quickly become outdated. Relying on older, more knowledgeable colleagues as a sole information source can provide dated, biased and incorrect information. This is not to say that clinical experience is not important - it is in fact part of the definition of EBP. However, rather than relying on clinical experience alone for decision making, health professionals need to use clinical experience together with other types of evidence-based information. 5

Is not all Published Research of Good Quality?

Not all research is of sufficient quality to inform clinical decision making. Therefore you need to critically appraise evidence before using it to inform your clinical decision making. The three major aspects of evidence that you need to critically appraise are:

- Validity - can you trust it?

- Impact - are the results clinically important?

- Applicability - can you apply it to your patient?

1. Guyatt, G.H., Haynes, R.B., Jaeschke, R.Z., & Cook, D.J. (2000). Users' guides to the medical literature: XXV. evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the users' guides to patient care. JAMA , 284, 1290-1296. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.10.1290

2. Sackett, D., Rosenberg, W., Gray, J., et al. (1996). Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't: it's about integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence. BMJ , 312, 71-72. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

3. Mayer, D. (2010). Essential evidence-based medicine (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

4. Hoffman, T., Bennett, S., & Del Mar, C. (2013). Evidence-based practice: across the health professions (2nd ed.). Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier.

5. Straus, S., Glasziou, P., Richardson, W., & Haynes, R. (2011). Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach it (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier

6. Bushell, M. (2019). Supporting your practice: Evidence-based medicine. Australian Pharmacist , 38, 3, 46-55.

- Next: Module 1: Ask >>

- Last Updated: Jul 24, 2023 4:08 PM

- URL: https://canberra.libguides.com/evidence

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

The Effectiveness of an Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Educational Program on Undergraduate Nursing Students’ EBP Knowledge and Skills: A Cluster Randomized Control Trial

Daniela cardoso.

1 Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing, Nursing School of Coimbra, Portugal Centre for Evidence-Based Practice: A Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, 3004-011 Coimbra, Portugal; tp.cfnese@osodracf (A.F.C.); tp.cfnese@oiregor (R.R.); moc.liamg@7ramed (M.A.R.); tp.cfnese@olotsopa (J.A.)

2 FMUC—Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, 3000-370 Coimbra, Portugal

Filipa Couto

3 Alfena Hospital—Trofa Health Group, Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing, Nursing School of Coimbra, 3000-232 Coimbra, Portugal; moc.liamg@otuoccdapilif

Ana Filipa Cardoso

Elzbieta bobrowicz-campos.

4 Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing, Nursing School of Coimbra, 3004-011 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] (E.B.-C.); tp.cfnese@stnasasiul (L.S.); tp.cfnese@ohnituocv (V.C.); tp.cfnese@otnipaleinad (D.P.)

Luísa Santos

Rogério rodrigues, verónica coutinho, daniela pinto, mary-anne ramis.

5 Mater Health, Evidence in Practice Unit & Queensland Centre for Evidence Based Nursing and Midwifery: A Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, 4101 Brisbane, Australia; [email protected]

Manuel Alves Rodrigues

João apóstolo, associated data.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because this issue was not considered within the informed consent signed by the participants of the study.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) prevents unsafe/inefficient practices and improves healthcare quality, but its implementation is challenging due to research and practice gaps. A focused educational program can assist future nurses to minimize these gaps. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of an EBP educational program on undergraduate nursing students’ EBP knowledge and skills. A cluster randomized controlled trial was undertaken. Six optional courses in the Bachelor of Nursing final year were randomly assigned to the experimental (EBP educational program) or control group. Nursing students’ EBP knowledge and skills were measured at baseline and post-intervention. A qualitative analysis of 18 students’ final written work was also performed. Results show a statistically significant interaction between the intervention and time on EBP knowledge and skills ( p = 0.002). From pre- to post-intervention, students’ knowledge and skills on EBP improved in both groups (intervention group: p < 0.001; control group: p < 0.001). At the post-intervention, there was a statistically significant difference in EBP knowledge and skills between intervention and control groups ( p = 0.011). Students in the intervention group presented monographs with clearer review questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and methodology compared to students in the control group. The EBP educational program showed a potential to promote the EBP knowledge and skills of future nurses.

1. Introduction

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is defined as “clinical decision-making that considers the best available evidence; the context in which the care is delivered; client preference; and the professional judgment of the health professional” [ 1 ] (p. 2). EBP implementation is recommended in clinical settings [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ] as it has been attributed to promoting high-value health care, improving the patient experience and health outcomes, as well as reducing health care costs [ 6 ]. Nevertheless, EBP is not the standard of care globally [ 7 , 8 , 9 ], and some studies acknowledge education as an approach to promote EBP adoption, implementation, and sustainment [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

It has been recommended that educational curricula for health students should be based on the five steps of EBP in order to support developing knowledge, skills, and positive attitudes toward EBP [ 16 ]. These steps are: translation of uncertainty into an answerable question; search for and retrieval of evidence; critical appraisal of evidence for validity and clinical importance; application of appraised evidence to practice; and evaluation of performance [ 16 ].

To respond to this recommendation, undergraduate nursing curricula should include courses, teaching strategies, and training that focus on the development of research and EBP skills for nurses to be able to incorporate valid and relevant research findings in practice. Nevertheless, teaching research and EBP to undergraduate nursing students is a challenging task. Some studies report that undergraduate students have negative attitudes/beliefs toward research and EBP, especially toward the statistical components of the research courses and the complex terminology used. Additionally, students may not understand the importance of the link between research and clinical practice [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. In fact, a lack of EBP and research knowledge is commonly reported by nurses and nursing students as a barrier to EBP. It is imperative to provide the future nurses with research and EBP skills in order to overcome the barriers to EBP use in clinical settings.

At an international level, several studies have been performed with undergraduate nursing students to assess the effectiveness of EBP interventions on multiple outcomes, such as EBP knowledge and skills [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. The Classification Rubric for EBP Assessment Tools in Education (CREATE) [ 24 ] suggests EBP knowledge should be assessed cognitively using paper and pencil tests, as EBP knowledge is defined as “learners’ retention of facts and concepts about EBP” [ 24 ] (p. 5). Additionally, the CREATE framework suggests EBP skills should be assessed using performance tests, as skills are defined as “the application of knowledge” [ 24 ] (p. 5). Despite these recommendations, few studies have assessed EBP knowledge and skills using both cognitive and performance instruments.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of an EBP educational program on undergraduate nursing students’ EBP knowledge and skills using a specific cognitive and performance instrument. The intervention used in this study was recently developed [ 25 ], and this is the first study designed to assess its effectiveness in undergraduate EBP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. design.

A cluster randomized controlled trial with two-armed parallel group design was undertaken (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT03411668","term_id":"NCT03411668"}} NCT03411668 ).

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated using the software G*Power 3.1.9.2. (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Dusseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) Recognizing that there were no studies performed a priori using a cognitive and performance instrument to assess the effectiveness of an EBP educational program on undergraduate nursing students’ EBP knowledge and skills, we used an effect size of 0.25, which is a small effect size as proposed by Cohen [ 26 ]. A power analysis based on a type I error of 0.05; power of 0.80; effect size f = 0.25; and ANOVA repeated measures between factors determined a sample size of 98 as total.

Taking into account that our study used clusters (optional courses) and that each one had an average of 25 students, we needed at least four clusters to cover the total sample size of 98. However, to cover potential losses to follow-up, we included a total of six optional courses.

2.3. Participants’ Recruitment and Randomization

We recruited participants from one Portuguese nursing school in 2018. From the 12 optional clinical nursing courses (such as Community Nursing Intervention in Vulnerable Groups; Ageing; Health and Citizenship; The Child with Special Needs: Diagnoses and Interventions in Pediatric Nursing; Liaison Psychiatry Nursing; Nursing in the Emergency Room; etc.) in the 8th semester of the nursing program (last year before graduation), students from three clinical nursing courses were randomly assigned to the experimental group (EBP educational program) and students from another three clinical nursing courses were randomly assigned to the control group (no intervention— education as usual ) before the baseline assessment. An independent researcher performed this assignment using a random number generator from the random.org website [ 27 ]. This assignment was performed based on a list of the 12 optional courses provided through the nursing school’s website.

2.4. Intervention Condition

The participants in the intervention group received education as usual plus the EBP educational program, which was developed by Cardoso, Rodrigues, and Apóstolo [ 25 ]. This intervention included EBP contents regarding models of thinking about EBP, systematic reviews types, review question development, searching for studies, study selection process, data extraction, and data synthesis.

This program was implemented in 6 sessions over 17 weeks:

- Sessions 1–3—total of 12 h (4 h per session) during the first 7 weeks using expository methods with practice tasks to groups of 20–30 students.

- Sessions 4–6—total of 6 h (2 h per session) during the last 10 weeks using active methods through mentoring to groups of 2–3 students.

Due to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants regarding treatment assignment nor was it feasible to blind the individuals delivering treatment.

2.5. Control Condition

The participants in the control group received only education as usual; i.e., students allocated to this control condition received the standard educational contents (theoretical, theoretical–practical, practical) delivered by the nursing educators of the selected nursing school.

2.6. Assessment

All participants were assessed before (week 0) and after the intervention (week 18) using a self-report instrument. EBP knowledge and skills were assessed by the Adapted Fresno Test for undergraduate nursing students [ 28 ]. This instrument was adapted from the Fresno Test, which was originally developed in 2003 to measure knowledge and skills on EBP in family practice residents [ 29 ]. The Adapted Fresno Test for undergraduate nursing students has seven short answer questions and two fill-in-the-blank questions [ 28 ]. At the beginning of the instrument, two scenarios, which suggest clinical uncertainty, are presented. These two scenarios are used to guide the answers to questions 1 to 4: (1) write a clinical question; (2) identify and discuss the strengths and weaknesses of information sources as well as the advantages and disadvantages of information sources; (3) identify the type of study most suitable for answering the question of one of the clinical scenarios and justify the choice; and (4) describe a possible search strategy in Medline for one of the clinical scenarios, explaining the rationale. The next three short answer questions require that the students identify topics for determining the relevance and validity of a research study and address the magnitude and value of research findings. The last two questions are fill-in-the-blank questions. The answers are scored using a modified standardized grading system [ 28 ], which was adapted from the original [ 29 ]. The instrument has a total minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 101. The inter-rater correlation for the total score of the Adapted Fresno Test was 0.826 [ 28 ]. The rater that graded the answers to the Adapted Fresno Test was blinded to treatment assignment.

Despite the fact that in the study proposal we did not consider any kind of qualitative analysis in order to assess EBP knowledge and skills in a more practical context, we decided during the development of the study to perform a qualitative analysis of monographs at the posttest. The monographs were developed by small groups of nursing students and were the final written work submitted by the students for their bachelor’s degree course. In this work, the students were asked to define a review question regarding the context of clinical practice where they were performing their clinical training. Students then proceeded to answer the review question through a systematic process of searching and selecting relevant studies and extracting and synthesizing the data. From the 58 submitted monographs (30 from the control group and 28 from the intervention group), 18 were randomized for evaluation (nine from the control group and nine from the intervention group) by an independent researcher using the random.org website [ 27 ] based on a list provided by the research team. Three independent experts (one psychologist with a doctoral qualification and two qualified nurses, one with a master’s degree) performed a qualitative analysis of the selected monographs. All experts had experience with the EBP approach and were blinded to treatment assignment. The experts independently used an evaluation form to guide the qualitative analysis of each monograph. This form presented 11 guiding criteria regarding review questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, methodology (namely search strategy, study selection process, data extraction, and data synthesis), results presentation, and congruency between the review questions and the answers to them that were provided in the conclusion section. Thereafter, the experts met to discuss any discrepancies in their qualitative analysis until consensus was reached.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; version 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences in sociodemographic characteristics of study participants and outcome data at baseline were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-squared test for nominal data and independent the t -test for continuous data.

Taking into account the central limit theorem and that ANOVA tests are robust to violation of assumptions [ 30 ], we decided to perform two-way mixed ANOVA to compare the outcome between and within groups. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyze how many participants had improved their EBP knowledge and skills item-by-item, how many remained the same, and how many had decreased performance within each group. Statistical significance was determined by p -values less than 0.05.

To minimize the noncompliance impact, an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was used to analyze participants in the groups that they were initially randomized to [ 31 ] by using the last observation carried forward imputation method.

2.8. Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Coimbra (Reference: CE-037/2017). The institution where the study was carried out provided written approval. All participants gave informed consent, and the data were managed in a confidential way.

Twelve potential clusters (optional courses in the 8th semester of the nursing program) were identified as eligible for this study. Of these, three were randomized for the intervention group and three for the control group. During the intervention, eight participants (two in the intervention group and six in the control group) were lost to follow-up because they did not fill-in the instrument in the post-intervention. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through each stage of the trial.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram showing the flow of participants through each stage of the trial. ITT: intention-to-treat.

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

As Table 1 displays, 148 undergraduate nursing students with an average age of 21.95 years (SD = 2.25; range: 21–41) participated in the study. A large majority of the sample were female ( n = 118, 79.7%), had a 12th grade educational level ( n = 144, 97.3%), and had participated in some form of EBP training ( n = 121, 81.8%).

Socio-demographic characterization of the sample—ITT analysis.

* Defined as any kind and duration of evidence-based practice (EBP) training, such as EBP contents in a course, a workshop, a seminar.

At baseline, the experimental and control groups were comparable regarding sex, age, education, EBP training, and performance on the Adapted Fresno Test ( Table 1 and Table 3). The baseline data were similar with dropouts excluded; therefore, only ITT analysis results are presented.

3.2. EBP Knowledge and Skills

3.2.1. adapted fresno test.

The two-way mixed ANOVA showed a statistically significant interaction between the intervention and time on EBP knowledge and skills, F (1, 146) = 9.550, p = 0.002, partial η 2 = 0.061 ( Table 2 ). Excluding the dropouts, the two-way mixed ANOVA analysis was similar. Thus, only the ITT analysis results are presented.

Main effects of time and group and interaction effects on EBP knowledge and skills—ITT analysis.

To determine the difference between groups at baseline and post-intervention, two separate between-subjects ANOVAs (i.e., two separate one-way ANOVAs) were performed. At the pre-intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in EBP knowledge and skills between groups: F (1,146) = 0.221, p = 0.639, partial η 2 = 0.002. At the post-intervention, there was a statistically significant difference in EBP knowledge and skills between groups: F (1,146) = 6.720, p = 0.011, partial η 2 = 0.044 ( Table 3 ).

Repeated measures ANOVA and between-subjects ANOVA—ITT analysis.

To determine the differences within groups from the baseline to post-intervention, two separate within-subjects ANOVAs (repeated measures ANOVAs) were performed. There was a statistically significant effect of time on EBP knowledge and skills for the intervention group: F (1,73) = 53.028, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.421 and for the control group: F (1,73) = 13.832, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.159 ( Table 3 ).

The results of repeated measures ANOVA and between-subjects ANOVA analysis are similar if we exclude the dropouts; therefore, only ITT analysis results are presented.

The results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for each item of the Adapted Fresno Test are presented in Table 4 . The results of this analysis revealed that students in both the intervention and control groups significantly improved their knowledge and skills in writing a focused clinical question (Item 1) (intervention group: Z = −4.572, p < 0.000; control group: Z = −2.338, p = 0.019), in building a search strategy (item 3) (intervention group: Z = −4.740, p < 0.000; control group: Z = −4.757, p < 0.000), in identifying and justifying the study design most suitable for answering the question of one of the clinical scenarios (item 4) (intervention group: Z = −4.508, p < 0.000; control group: Z = −3.738, p < 0.000), and in describing the characteristics of a study to determine its relevance (item 5) (intervention group: Z = −2.699, p = 0.007; control group: Z = −1.980, p = 0.048).

Within groups comparison with Wilcoxon signed-rank test for each item of the Adapted Fresno Test—ITT analysis.

The students in the control group significantly improved their knowledge and skills in describing the characteristics of a study to determine its validity (item 6) ( Z = −2.714, p = 0.007). The students in the intervention group significantly improved their knowledge and skills in describing the characteristics of a study to determine its magnitude and significance (item 7) ( Z = −2.543, p = 0.011). No other significant differences were detected.

The results of the within groups comparison with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test are similar if we exclude the dropouts; therefore, only ITT analysis results are presented.

3.2.2. Qualitative Analysis of Monographs

Based on the experts’ consensus report of each monograph, the analysis of the intervention group monographs showed that the students’ groups clearly defined their review questions and inclusion/exclusion criteria. These groups of students effectively searched for studies using appropriate databases, keywords, Boolean operators, and truncation. Additionally, we found thorough descriptions from students concerning the selection process, data extraction, and data synthesis. However, only three students’ groups provided a good description of the review findings with an appropriate data synthesis as well as a clear answer to the review question in the conclusion section of their monographs. It is noted that the criteria for the results and conclusion sections were more difficult to successfully achieve, even in the intervention group.

The monographs of the control groups showed weaknesses throughout. From the nine monographs of the control group, only two presented the review question in a way that was clearly defined. In all of the monographs, the inclusion/exclusion criteria were either not very informative, unclear, or did not match with the defined review questions. Additionally, the search strategies were not clear and demonstrated limited understanding, such as lack of use of appropriate synonyms, absent truncations, and no definition of the search field for each word or expression to be searched. None of the monographs from the control group reported information about the methods used to study the selection process, to extract data, or to synthesize data. In the conclusion section, students from the control group also demonstrated difficulties in synthesizing the data and limitations by providing a clear answer to the review question.

4. Discussion

This study sought to evaluate the effectiveness of an EBP educational program on undergraduate nursing students’ EBP knowledge and skills. Even though both groups improved after the intervention in EBP knowledge and skills, the study results showed that the improvement was greater in the intervention group. This result was reinforced by the results of the qualitative analysis of monographs.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use a cognitive and performance assessment instrument (Adapted Fresno Test) with undergraduate nursing students, as suggested by CREATE [ 24 ]. Additionally, it is the first study conducted using the EBP education program [ 25 ]. Therefore, comparison of our findings with similar studies in terms of the type of assessment instrument and intervention is limited.

However, comparing our study with other previous research using other types of instruments and interventions demonstrates similar results [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. In a quasi-experimental study [ 20 ], it was found that an EBP educational teaching strategy showed positive results in improving EBP knowledge in undergraduate nursing students. A study showed that undergraduate nursing students who received an EBP-focused interactive teaching intervention improved their EBP knowledge [ 21 ]. Another study indicated that a 15-week educational intervention in undergraduate nursing students (second- and third-year) significantly improved their EBP knowledge and skills [ 22 ]. In addition, a study by Zhang, Zeng, Chen, and Li revealed a significant improvement in undergraduate nursing students’ EBP knowledge after participating in a two-phase intervention: a self-directed learning process and a workshop for critical appraisal of literature [ 23 ].

Despite the effectiveness of the program in improving EBP knowledge and skills, the students included in the present study had low levels of EBP knowledge and skills as assessed by the Adapted Fresno Test at the pretest and posttest. These low levels of EBP knowledge and skills, especially at the pretest, might have influenced our study results. As a matter of fact, the Adapted Fresno Test is a demanding test since it requires that students retrieve and apply knowledge while doing a task associated with EBP based on scenarios involving clinical uncertainty. Consequently, this kind of test is very useful to truly assess EBP knowledge retention and abilities in clinical scenarios that do not allow guessing the answers. Notwithstanding, due to these characteristics, the Adapted Fresno Test may possibly be less sensitive when small changes occur or when students have low levels of EBP knowledge and skills. Nevertheless, even using instruments with Likert scales, other studies also showed that students have low levels of EBP knowledge and skills [ 21 , 22 , 23 ].

The low levels of EBP knowledge and skills of the undergraduate nursing students may be a reflection of a persistent, traditional education with regard to research. By this we mean that the focus of training remains on primary research—preparing students to be “research generators” instead of preparing them to be “evidence users” [ 32 ]. Furthermore, the designed and tested intervention used in this study was limited in time (only 17 weeks), was provided by only two instructors, and was delivered to fourth-year undergraduate nursing students, which are limitations for curriculum-wide integration of EBP.

Indeed, a curriculum that promotes EBP should facilitate students’ acquisition of EBP knowledge and skills over time and with levels of increasing complexity through their participation in EBP courses and during their clinical practice experiences [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. As Moch, Cronje, and Branson suggest, “It is only in such practical settings that students can experience the challenges intrinsic to applying scientific evidence to the care of real patients. In these clinical settings, students can experience both the frustrations and the triumphs inevitable to integrating scientific knowledge into patient care.” [ 35 ] (p. 11). Therefore, in future studies, other broad approaches for curriculum-wide integration of EBP as well as its long-term effects should be evaluated.

Previously in the Discussion, we highlighted the limitations of the proposed intervention in terms of time constraints (only 17 weeks), instructors’ constraints (only two instructors provided the intervention), and participants’ constraints (fourth-year undergraduate nursing students). In addition, the study was also restricted to one Portuguese nursing school, which can limit the generalization of the results. However, our study tried to address some of the fragilities identified in other studies [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ] on the effectiveness of EBP educational interventions by including a control group and by measuring EBP knowledge and skills with an objective measure and not a self-reported measure.

Bearing this in mind, future studies in multiple sites should assess the long-term effects of the EBP educational intervention and the impact on EBP knowledge and skills of potential variations in contents and teaching methods. In addition, studies using more broad interventions for curriculum-wide integration of EBP should also be performed.

5. Conclusions

Our findings show that the EBP educational program was effective in improving the EBP knowledge and skills of undergraduate nursing students. Therefore, the use of an EBP approach as a complement to the research education of undergraduate nursing students should be promoted by nursing schools and educators. This will help to prepare the future nurses with the EBP knowledge and skills that are essential to overcome the barriers to EBP use in clinical settings, and consequently, to contribute to better health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This paper contributed toward the D.C. PhD in Health Sciences—Nursing. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing (UICISA: E), hosted by the Nursing School of Coimbra (ESEnfC) and funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT). Moreover, the authors gratefully thank Catarina Oliveira for all the support as a Ph.D. supervisor and Isabel Fernandes, Maria da Nazaré Cerejo, and Irma Brito for help and facilitation of data collection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C., M.A.R., and J.A.; methodology, D.C., M.A.R., and J.A.; validation, D.C., M.A.R., and J.A.; formal analysis, D.C., F.C., and A.F.C.; investigation, D.C., F.C., A.F.C., E.B.-C., L.S., R.R., V.C., D.P., M.-A.R., M.A.R., and J.A.; resources, D.C., M.A.R., and J.A.; data curation, D.C., F.C., and A.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.; writing—review and editing, F.C., A.F.C., E.B.-C., L.S., R.R., V.C., D.P., M.-A.R., M.A.R., and J.A.; supervision, M.A.R. and J.A.; project administration, D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work was funded by National Funds through the FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of the project Ref. UIDP/00742/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethical Committee of Faculty of Medicine of the University of Coimbra (protocol code: CE-037/2017 and date of approval: 22 May 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Brechin A. Introducing critical practice. In: Brechin A, Brown H, Eby MA (eds). London: Sage/Open University; 2000

Introduction to evidence informed decision making. 2012. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45245.html (accessed 8 March 2022)

Cullen L, Adams SL. Planning for implementation of evidence-based practice. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2012; 42:(4)222-230 https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e31824ccd0a

DiCenso A, Guyatt G, Ciliska D. Evidence-based nursing. A guide to clinical practice.St. Louis (MO): Mosby; 2005

Implementing evidence-informed practice: International perspectives. In: Dill K, Shera W (eds). Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press; 2012

Dufault M. Testing a collaborative research utilization model to translate best practices in pain management. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004; 1:S26-S32 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04049.x

Epstein I. Promoting harmony where there is commonly conflict: evidence-informed practice as an integrative strategy. Soc Work Health Care. 2009; 48:(3)216-231 https://doi.org/10.1080/00981380802589845

Epstein I. Reconciling evidence-based practice, evidence-informed practice, and practice-based research: the role of clinical data-mining. Social Work. 2011; 56:(3)284-288 https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/56.3.284

Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. 2005. https://tinyurl.com/mwpf4be4 (accessed 6 March 2022)

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map?. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006; 26:(1)13-24 https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.47

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, MacFarlane F, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in health service organisations. A systematic literature review.Malden (MA): Blackwell; 2005

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis?. BMJ. 2014; 348 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3725

Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH. Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine and patient choice. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2002; 7:36-38 https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm.7.2.36

Hitch D, Nicola-Richmond K. Instructional practices for evidence-based practice with pre-registration allied health students: a review of recent research and developments. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017; 22:(4)1031-1045 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9702-9

Jerkert J. Negative mechanistic reasoning in medical intervention assessment. Theor Med Bioeth. 2015; 36:(6)425-437 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-015-9348-2

McSherry R, Artley A, Holloran J. Research awareness: an important factor for evidence-based practice?. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2006; 3:(3)103-115 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00059.x

McSherry R, Simmons M, Pearce P. An introduction to evidence-informed nursing. In: McSherry R, Simmons M, Abbott P London: Routledge; 2002

Implementing excellence in your health care organization: managing, leading and collaborating. In: McSherry R, Warr J (eds). Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2010

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Stillwell SB, Williamson KM. Evidence-based practice: step by step: the seven steps of evidence-based practice. AJN, American Journal of Nursing. 2010; 110:(1)51-53 https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000366056.06605.d2

Implementing evidence-based practices: six ‘drivers’ of success. Part 3 in a Series on Fostering the Adoption of Evidence-Based Practices in Out-Of-School Time Programs. 2007. https://tinyurl.com/mu2y6ahk (accessed 8 March 2022)

Muir-Gray JA. Evidence-based healthcare. How to make health policy and management decisions.Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997

Nevo I, Slonim-Nevo V. The myth of evidence-based practice: towards evidence-informed practice. British Journal of Social Work. 2011; 41:(6)1176-1197 https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq149

Newhouse RP, Dearholt S, Poe S, Pugh LC, White K. The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice Rating Scale.: The Johns Hopkins Hospital: Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing; 2005

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code. 2018. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code (accessed 7 March 2022)

Nutley S, Walter I, Davies HTO. Promoting evidence-based practice: models and mechanisms from cross-sector review. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009; 19:(5)552-559 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509335496

Reed JE, Howe C, Doyle C, Bell D. Successful Healthcare Improvements From Translating Evidence in complex systems (SHIFT-Evidence): simple rules to guide practice and research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019; 31:(3)238-244 https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy160

Rosswurm MA, Larrabee JH. A model for change to evidence-based practice. Image J Nurs Sch. 1999; 31:(4)317-322 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00510.x

Rubin A. Improving the teaching of evidence-based practice: introduction to the special issue. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007; 17:(5)541-547 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507300145

Shlonsky A, Mildon R. Methodological pluralism in the age of evidence-informed practice and policy. Scand J Public Health. 2014; 42:18-27 https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494813516716

Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ. 2009; 181:(3-4)165-168 https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.081229

Titler MG, Everett LQ. Translating research into practice. Considerations for critical care investigators. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001; 13:(4)587-604 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-5885(18)30026-1

Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman V Infusing research into practice to promote quality care. Nurs Res. 1994; 43:(5)307-313 https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199409000-00009

Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman VJ The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001; 13:(4)497-509 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-5885(18)30017-0

Ubbink DT, Guyatt GH, Vermeulen H. Framework of policy recommendations for implementation of evidence-based practice: a systematic scoping review. BMJ Open. 2013; 3:(1) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001881

Wang LP, Jiang XL, Wang L, Wang GR, Bai YJ. Barriers to and facilitators of research utilization: a survey of registered nurses in China. PLoS One. 2013; 8:(11) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081908

Warren JI, McLaughlin M, Bardsley J, Eich J, Esche CA, Kropkowski L, Risch S. The strengths and challenges of implementing EBP in healthcare systems. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016; 13:(1)15-24 https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12149

Webber M, Carr S. Applying research evidence in social work practice: Seeing beyond paradigms. In: Webber M (ed). London: Palgrave; 2015

Evidence-based practice vs. evidence-based practice: what's the difference?. 2014. https://tinyurl.com/2p8msjaf (accessed 8 March 2022)

Evidence-informed practice: simplifying and applying the concept for nursing students and academics

Elizabeth Adjoa Kumah

Nurse Researcher, Faculty of Health and Social Care, University of Chester, Chester

View articles · Email Elizabeth Adjoa

Robert McSherry

Professor of Nursing and Practice Development, Faculty of Health and Social Care, University of Chester, Chester

View articles

Josette Bettany-Saltikov

Senior Lecturer, School of Health and Social Care, Teesside University, Middlesbrough

Paul van Schaik

Professor of Research, School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Law, Teesside University, Middlesbrough

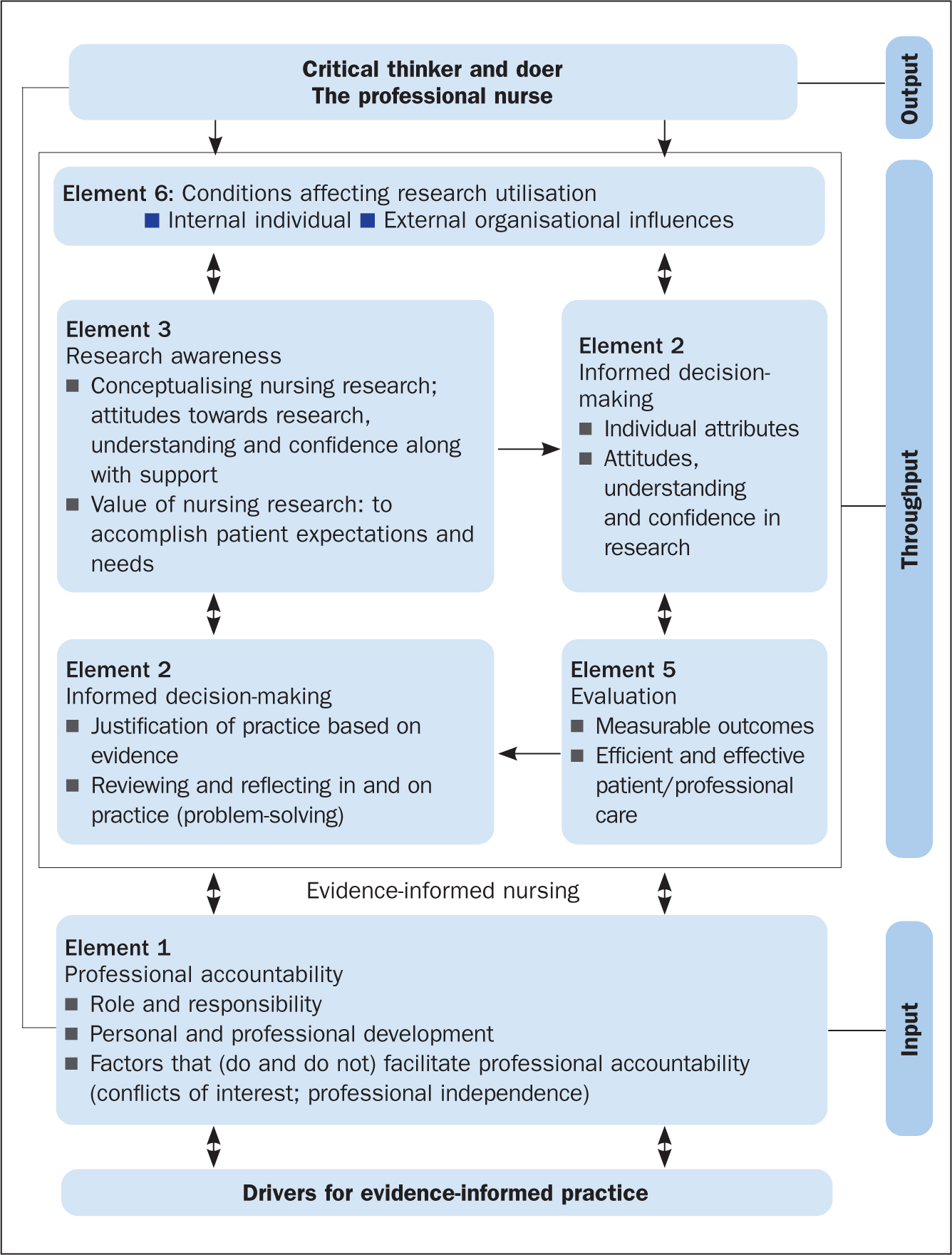

Background:

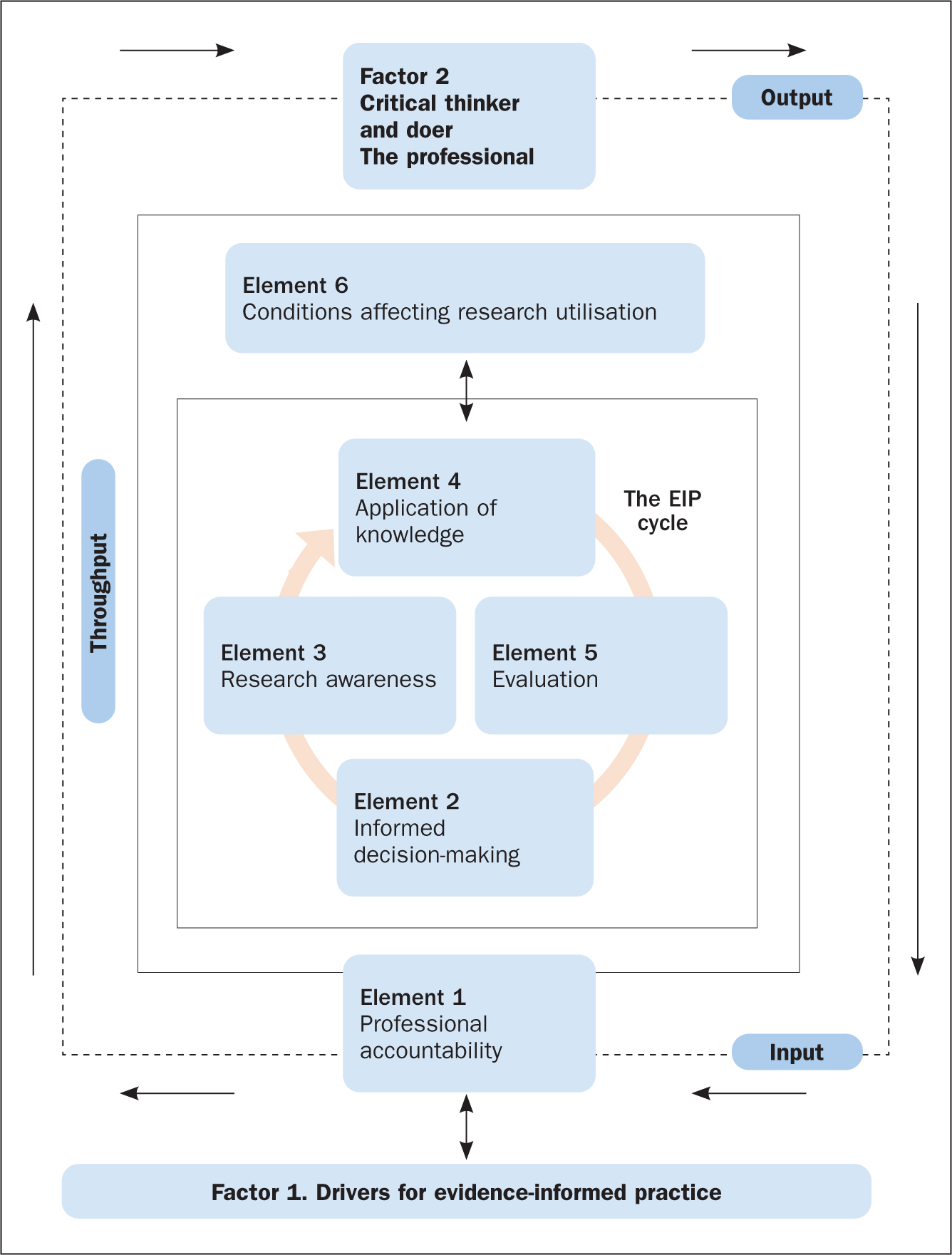

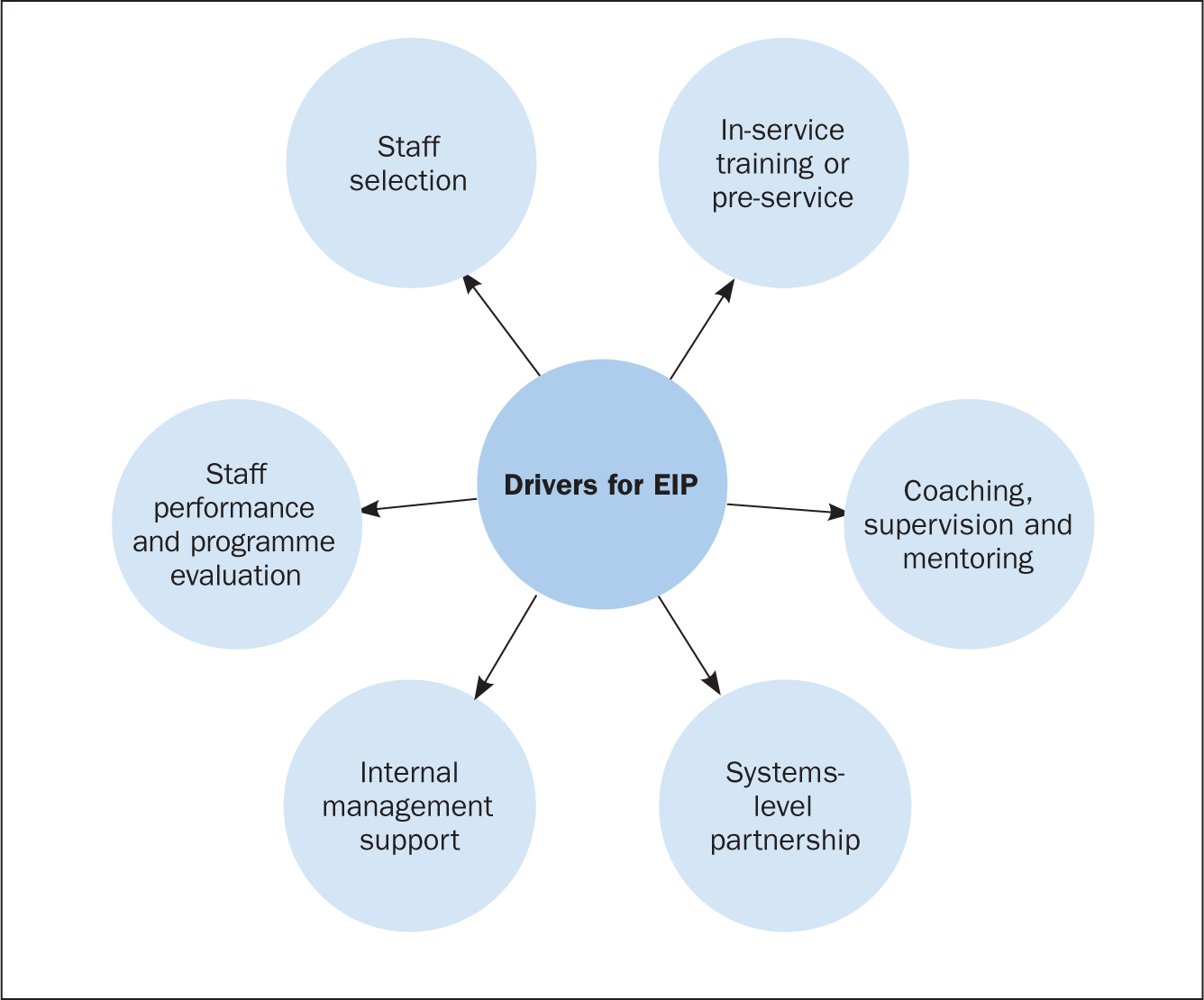

Nurses' ability to apply evidence effectively in practice is a critical factor in delivering high-quality patient care. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is recognised as the gold standard for the delivery of safe and effective person-centred care. However, decades following its inception, nurses continue to encounter difficulties in implementing EBP and, although models for its implementation offer stepwise approaches, factors, such as the context of care and its mechanistic nature, act as barriers to effective and consistent implementation. It is, therefore, imperative to find a solution to the way evidence is applied in practice. Evidence-informed practice (EIP) has been mooted as an alternative to EBP, prompting debate as to which approach better enables the transfer of evidence into practice. Although there are several EBP models and educational interventions, research on the concept of EIP is limited. This article seeks to clarify the concept of EIP and provide an integrated systems-based model of EIP for the application of evidence in clinical nursing practice, by presenting the systems and processes of the EIP model. Two scenarios are used to demonstrate the factors and elements of the EIP model and define how it facilitates the application of evidence to practice. The EIP model provides a framework to deliver clinically effective care, and the ability to justify the processes used and the service provided by referring to reliable evidence.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) was first mentioned in the literature by Muir-Gray, who defined EBP as ‘an approach to decision-making in which the clinician uses the best available evidence in consultation with the patient to decide upon the option which suits the patient best’ (1997:97). Since this initial definition was set out in 1997, EBP has gained prominence as the gold standard for the delivery of safe and effective health care.

There are several models for implementing EBP. Examples include:

- Rosswurm and Larrabee's (1999) model

- The Iowa model ( Titler et al, 2001 )

- Collaborative research utilisation model ( Dufault, 2004 ); DiCenso et al's (2005) model

- Greenhalgh et al's (2005) model

- Johns Hopkins Nursing model ( Newhouse et al, 2005 )

- Melnyk et al's (2010) model.