Essays About Life Lessons: Top 5 Examples and 7 Prompts

Read our guide to see the top examples and prompts on essays about life lessons to communicate your thoughts effectively.

Jordan Peterson once said, “Experience is the best teacher, and the worst experiences teach the best lessons.” The many life lessons we’ll accumulate in our life will help us veer in the right direction to fulfill our destinies. Whether it’s creative or nonfiction, as long as it describes the author’s personal life experiences or worldview, recounting life lessons falls under the personal or narrative essay category.

To successfully write an essay on this topic, you must connect with your readers and allow them to visualize, understand, and get inspired by what you have learned about life. To do this, you must remember critical elements such as a compelling hook, engaging story, relatable characters, suitable setting, and significant points.

See below five examples of life lessons essays to inspire you:

1. Life Lessons That the First Love Taught Me by Anonymous on GradesFixer.Com

2. the dad’s life lessons and the role model for the children by anonymous on studymoose.com, 3. studying history and own mistakes as life lessons: opinion essay by anonymous on edubirdie.com, 4. life lessons by anonymous on phdessay.com, 5. valuable lessons learned in life by anonymous on eduzaurus.com, 1. life lessons from books, 2. my biggest mistake and the life lesson i learned, 3. the life lessons i’ve learned, 4. life lessons from a popular show, 5. using life lessons in starting a business, 6. life lessons you must know, 7. kids and life lessons.

“I thought I knew absolutely everything about loving someone by the age of fourteen. Clearly I knew nothing and I still have so much to learn about what it is like to actually love someone.”

The author relates how their first love story unfolds, including the many things they learned from it. An example is that no matter how compatible the couple is if they are not for each other, they will not last long and will break up eventually. The writer also shares that situations that test the relationship, such as jealousy, deserve your attention as they aid people in picking the right decisions. The essay further tells how the writer’s relationship became toxic and affected their mental and emotional stability, even after the breakup. To cope and heal, they stopped looking for connections and focused on their grades, family, friends, and self-love.

“I am extremely thankful that he could teach me all the basics like how to ride a bike, how to fish and shoot straight, how to garden, how to cook, how to drive, how to skip a rock, and even how to blow spitballs. But I am most thankful that could teach me to stand tall (even though I’m 5’3”), be full with my heart and be strong with my mind.”

In this essay, the writer introduces their role model who taught them almost everything they know in their seventeen years of life, their father. The writer shares that their father’s toughness, stubbornness, and determination helped them learn to stand up for themselves and others and not be a coward in telling the truth. Because of him, the author learned how to be kind, generous, and mature. Finally, the author is very grateful to their father, who help them to think for themselves and not believe everything they hear.

“In my opinion, I believe it is more important to study the past rather than the present because we can learn more from our mistakes.”

This short essay explains the importance of remembering past events to analyze our mistakes. The author mentions that when people do this, they learn and grow from it, which prevents them from repeating the same error in the present time. The writer also points out that everyone has made the mistake of letting others dictate how their life goes, often leading to failures.

“… I believe we come here to learn a valuable lesson. If we did not learn this lesson through out a life time, our souls would come back to repeat the process.”

This essay presents three crucial life lessons that everyone needs to know. The first is to stop being too comfortable in taking people and things for granted. Instead, we must learn to appreciate everything. The second is to realize that mistakes are part of everyone’s life. So don’t let the fear of making mistakes stop you from trying something new. The third and final lesson is from Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.” People learn and grow as they age, so everyone needs to remember to live their life as if it were their last with no regrets.

“Life lessons are not necessarily learned from bad experiences, it can also be learned from good experiences, accomplishments, mistakes of other people, and by reading too.”

The essay reminds the readers to live their life to the fullest and cherish people and things in their lives because life is too short. If you want something, do not let it slip away without trying. If it fails, do not suffer and move on. The author also unveils the importance of travelling, keeping a diary, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

7 Prompts for Essays About Life Lessons

Use the prompts below if you’re still undecided on what to write about:

As mentioned above, life lessons are not only from experiences but also from reading. So for this prompt, pick up your favorite book and write down the lessons you learned from it. Next, identify each and explain to your readers why you think it’s essential to incorporate these lessons into real life. Finally, add how integrating these messages affected you.

There are always lessons we can derive from mistakes. However, not everyone understands these mistakes, so they keep doing them. Think of all your past mistakes and choose one that had the most significant negative impact on you and the people around you. Then, share with your readers what it is, its causes, and its effects. Finally, don’t forget to discuss what you gained from these faults and how you prevent yourself from doing them again.

Compile all the life lessons you’ve realized from different sources. They can be from your own experience, a relative’s, a movie, etc. Add why these lessons resonate with you. Be creative and use metaphors or add imaginary scenarios. Bear in mind that your essay should convey your message well.

Popular shows are an excellent medium for teaching life lessons to a broad audience. In your essay, pick a well-known work and reflect on it. For example, Euphoria is a TV series that created hubbub for its intrigue and sensitive themes. Dissect what life lessons one can retrieve from watching the show and relate them to personal encounters. You can also compile lessons from online posts and discussions.

If the subject of “life lessons” is too general for you, scope a more specific area, such as entrepreneurship. Which life lessons are critical for a person in business? To make your essay easier to digest, interview a successful business owner and ask about the life lessons they’ve accumulated before and while pursuing their goals.

Use this prompt to present the most important life lessons you’ve collected throughout your life. Then, share why you selected these lessons. For instance, you can choose “Live life as if it’s your last” and explain that you realized this life lesson after suddenly losing a loved one.

Have you ever met someone younger than you who taught you a life lesson? If so, in this prompt, tell your reader the whole story and what life lesson you discovered. Then, you can reverse it and write an incident where you give a good life lesson to someone older than you – say what it was and if that lesson helped them. Read our storytelling guide to upgrade your techniques.

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A narrative essay tells a story. In most cases, this is a story about a personal experience you had. This type of essay , along with the descriptive essay , allows you to get personal and creative, unlike most academic writing .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a narrative essay for, choosing a topic, interactive example of a narrative essay, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about narrative essays.

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college , you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/narrative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write a descriptive essay | example & tips, how to write your personal statement | strategies & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Life

Essay Samples on Life Lesson

The most important lesson i learned in life: embracing resilience.

The journey of life is an intricate tapestry woven with threads of experiences, each contributing to the canvas of our growth and wisdom. Among these experiences, one lesson stands out as the most profound: the art of embracing resilience. In the mosaic of life, resilience...

- Life Lesson

Life Experiences That Taught a Lesson: How Experience Contributes to Our Growth

Life is a journey filled with countless experiences that shape who we are and how we navigate the world around us. Some of these experiences are simple and joyful, while others are challenging and transformative. This essay explores several life experiences that have taught valuable...

A Life Lesson I Have Learned and How It Continues to Shape Me

Life is a continuous journey of learning, filled with moments that impart wisdom and shape our perspectives. Some lessons are gentle whispers, while others are profound experiences that leave an everlasting imprint. In this narrative essay, I will share a significant life lesson that I...

- Life Changing Experience

Rising Above Negativity: A Journey in Music and Self-Belief

My Early Music Career Let me inform you about a time when I realized a life lesson. A couple of weeks ago, I started out producing music; I was once just starting as a producer, and I had no prior expertise in song theory. I...

Traveling Through Life: Learning, Evolving, and Reflecting

Life Lessons Learned on a Journey What is a journey. A journey is an act of traveling from one place to another and the time in between that act. We took a look at many texts relating to people going on a journey such as...

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

"Made In Heaven": An Analysis of Relationships and Life Lessons

Introduction The web series "Made In Heaven" on Amazon Prime has captivated the attention of the younger Indian audience. Created by Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti, the series has received both acclaim and criticism for its explicit depiction of sex, abusive dialogues, and portrayal of...

- Marriage and Family

Best topics on Life Lesson

1. The Most Important Lesson I Learned in Life: Embracing Resilience

2. Life Experiences That Taught a Lesson: How Experience Contributes to Our Growth

3. A Life Lesson I Have Learned and How It Continues to Shape Me

4. Rising Above Negativity: A Journey in Music and Self-Belief

5. Traveling Through Life: Learning, Evolving, and Reflecting

6. “Made In Heaven”: An Analysis of Relationships and Life Lessons

- Career Goals

- Personality

- Perseverance

- Teenage Love

- Fear of Failure

- Multitasking

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Spring Sale

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Telling the Story of Yourself: 6 Steps to Writing Personal Narratives

Jennifer Xue

Table of Contents

Why do we write personal narratives, 6 guidelines for writing personal narrative essays, inspiring personal narratives, examples of personal narrative essays, tell your story.

First off, you might be wondering: what is a personal narrative? In short, personal narratives are stories we tell about ourselves that focus on our growth, lessons learned, and reflections on our experiences.

From stories about inspirational figures we heard as children to any essay, article, or exercise where we're asked to express opinions on a situation, thing, or individual—personal narratives are everywhere.

According to Psychology Today, personal narratives allow authors to feel and release pains, while savouring moments of strength and resilience. Such emotions provide an avenue for both authors and readers to connect while supporting healing in the process.

That all sounds great. But when it comes to putting the words down on paper, we often end up with a list of experiences and no real structure to tie them together.

In this article, we'll discuss what a personal narrative essay is further, learn the 6 steps to writing one, and look at some examples of great personal narratives.

As readers, we're fascinated by memoirs, autobiographies, and long-form personal narrative articles, as they provide a glimpse into the authors' thought processes, ideas, and feelings. But you don't have to be writing your whole life story to create a personal narrative.

You might be a student writing an admissions essay , or be trying to tell your professional story in a cover letter. Regardless of your purpose, your narrative will focus on personal growth, reflections, and lessons.

Personal narratives help us connect with other people's stories due to their easy-to-digest format and because humans are empathising creatures.

We can better understand how others feel and think when we were told stories that allow us to see the world from their perspectives. The author's "I think" and "I feel" instantaneously become ours, as the brain doesn't know whether what we read is real or imaginary.

In her best-selling book Wired for Story, Lisa Cron explains that the human brain craves tales as it's hard-wired through evolution to learn what happens next. Since the brain doesn't know whether what you are reading is actual or not, we can register the moral of the story cognitively and affectively.

In academia, a narrative essay tells a story which is experiential, anecdotal, or personal. It allows the author to creatively express their thoughts, feelings, ideas, and opinions. Its length can be anywhere from a few paragraphs to hundreds of pages.

Outside of academia, personal narratives are known as a form of journalism or non-fiction works called "narrative journalism." Even highly prestigious publications like the New York Times and Time magazine have sections dedicated to personal narratives. The New Yorke is a magazine dedicated solely to this genre.

The New York Times holds personal narrative essay contests. The winners are selected because they:

had a clear narrative arc with a conflict and a main character who changed in some way. They artfully balanced the action of the story with reflection on what it meant to the writer. They took risks, like including dialogue or playing with punctuation, sentence structure and word choice to develop a strong voice. And, perhaps most important, they focused on a specific moment or theme – a conversation, a trip to the mall, a speech tournament, a hospital visit – instead of trying to sum up the writer’s life in 600 words.

In a nutshell, a personal narrative can cover any reflective and contemplative subject with a strong voice and a unique perspective, including uncommon private values. It's written in first person and the story encompasses a specific moment in time worthy of a discussion.

Writing a personal narrative essay involves both objectivity and subjectivity. You'll need to be objective enough to recognise the importance of an event or a situation to explore and write about. On the other hand, you must be subjective enough to inject private thoughts and feelings to make your point.

With personal narratives, you are both the muse and the creator – you have control over how your story is told. However, like any other type of writing, it comes with guidelines.

1. Write Your Personal Narrative as a Story

As a story, it must include an introduction, characters, plot, setting, climax, anti-climax (if any), and conclusion. Another way to approach it is by structuring it with an introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction should set the tone, while the body should focus on the key point(s) you want to get across. The conclusion can tell the reader what lessons you have learned from the story you've just told.

2. Give Your Personal Narrative a Clear Purpose

Your narrative essay should reflect your unique perspective on life. This is a lot harder than it sounds. You need to establish your perspective, the key things you want your reader to take away, and your tone of voice. It's a good idea to have a set purpose in mind for the narrative before you start writing.

Let's say you want to write about how you manage depression without taking any medicine. This could go in any number of ways, but isolating a purpose will help you focus your writing and choose which stories to tell. Are you advocating for a holistic approach, or do you want to describe your emotional experience for people thinking of trying it?

Having this focus will allow you to put your own unique take on what you did (and didn't do, if applicable), what changed you, and the lessons learned along the way.

3. Show, Don't Tell

It's a narration, so the narrative should show readers what happened, instead of telling them. As well as being a storyteller, the author should take part as one of the characters. Keep this in mind when writing, as the way you shape your perspective can have a big impact on how your reader sees your overarching plot. Don't slip into just explaining everything that happened because it happened to you. Show your reader with action.

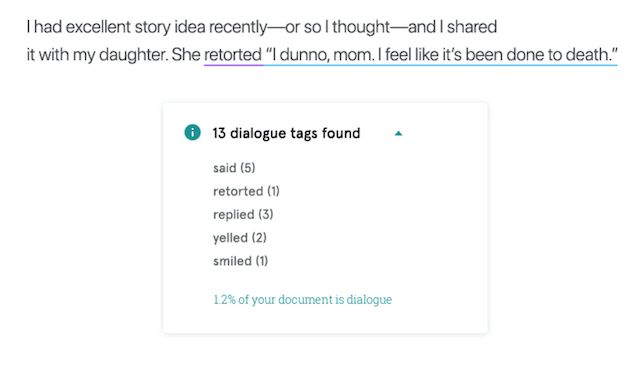

You can check for instances of telling rather than showing with ProWritingAid. For example, instead of:

"You never let me do anything!" I cried disdainfully.

"You never let me do anything!" To this day, my mother swears that the glare I levelled at her as I spat those words out could have soured milk.

Using ProWritingAid will help you find these instances in your manuscript and edit them without spending hours trawling through your work yourself.

4. Use "I," But Don't Overuse It

You, the author, take ownership of the story, so the first person pronoun "I" is used throughout. However, you shouldn't overuse it, as it'd make it sound too self-centred and redundant.

ProWritingAid can also help you here – the Style Report will tell you if you've started too many sentences with "I", and show you how to introduce more variation in your writing.

5. Pay Attention to Tenses

Tense is key to understanding. Personal narratives mostly tell the story of events that happened in the past, so many authors choose to use the past tense. This helps separate out your current, narrating voice and your past self who you are narrating. If you're writing in the present tense, make sure that you keep it consistent throughout.

6. Make Your Conclusion Satisfying

Satisfy your readers by giving them an unforgettable closing scene. The body of the narration should build up the plot to climax. This doesn't have to be something incredible or shocking, just something that helps give an interesting take on your story.

The takeaways or the lessons learned should be written without lecturing. Whenever possible, continue to show rather than tell. Don't say what you learned, narrate what you do differently now. This will help the moral of your story shine through without being too preachy.

GoodReads is a great starting point for selecting read-worthy personal narrative books. Here are five of my favourites.

Owl Moon by Jane Yolen

Jane Yolen, the author of 386 books, wrote this poetic story about a daughter and her father who went owling. Instead of learning about owls, Yolen invites readers to contemplate the meaning of gentleness and hope.

Night by Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel was a teenager when he and his family were sent to Auschwitz concentration camp in 1944. This Holocaust memoir has a strong message that such horrific events should never be repeated.

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

This classic is a must-read by young and old alike. It's a remarkable diary by a 13-year-old Jewish girl who hid inside a secret annexe of an old building during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in 1942.

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

This is a personal narrative written by a brave author renowned for her clarity, passion, and honesty. Didion shares how in December 2003, she lost her husband of 40 years to a massive heart attack and dealt with the acute illness of her only daughter. She speaks about grief, memories, illness, and hope.

Educated by Tara Westover

Author Tara Westover was raised by survivalist parents. She didn't go to school until 17 years of age, which later took her to Harvard and Cambridge. It's a story about the struggle for quest for knowledge and self-reinvention.

Narrative and personal narrative journalism are gaining more popularity these days. You can find distinguished personal narratives all over the web.

Curating the best of the best of personal narratives and narrative essays from all over the web. Some are award-winning articles.

Narratively

Long-form writing to celebrate humanity through storytelling. It publishes personal narrative essays written to provoke, inspire, and reflect, touching lesser-known and overlooked subjects.

Narrative Magazine

It publishes non,fiction narratives, poetry, and fiction. Among its contributors is Frank Conroy, the author of Stop-Time , a memoir that has never been out of print since 1967.

Thought Catalog

Aimed at Generation Z, it publishes personal narrative essays on self-improvement, family, friendship, romance, and others.

Personal narratives will continue to be popular as our brains are wired for stories. We love reading about others and telling stories of ourselves, as they bring satisfaction and a better understanding of the world around us.

Personal narratives make us better humans. Enjoy telling yours!

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

Jennifer Xue is an award-winning e-book author with 2,500+ articles and 100+ e-books/reports published under her belt. She also taught 50+ college-level essay and paper writing classes. Her byline has appeared in Forbes, Fortune, Cosmopolitan, Esquire, Business.com, Business2Community, Addicted2Success, Good Men Project, and others. Her blog is JenniferXue.com. Follow her on Twitter @jenxuewrites].

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 great narrative essay examples + tips for writing.

General Education

A narrative essay is one of the most intimidating assignments you can be handed at any level of your education. Where you've previously written argumentative essays that make a point or analytic essays that dissect meaning, a narrative essay asks you to write what is effectively a story .

But unlike a simple work of creative fiction, your narrative essay must have a clear and concrete motif —a recurring theme or idea that you’ll explore throughout. Narrative essays are less rigid, more creative in expression, and therefore pretty different from most other essays you’ll be writing.

But not to fear—in this article, we’ll be covering what a narrative essay is, how to write a good one, and also analyzing some personal narrative essay examples to show you what a great one looks like.

What Is a Narrative Essay?

At first glance, a narrative essay might sound like you’re just writing a story. Like the stories you're used to reading, a narrative essay is generally (but not always) chronological, following a clear throughline from beginning to end. Even if the story jumps around in time, all the details will come back to one specific theme, demonstrated through your choice in motifs.

Unlike many creative stories, however, your narrative essay should be based in fact. That doesn’t mean that every detail needs to be pure and untainted by imagination, but rather that you shouldn’t wholly invent the events of your narrative essay. There’s nothing wrong with inventing a person’s words if you can’t remember them exactly, but you shouldn’t say they said something they weren’t even close to saying.

Another big difference between narrative essays and creative fiction—as well as other kinds of essays—is that narrative essays are based on motifs. A motif is a dominant idea or theme, one that you establish before writing the essay. As you’re crafting the narrative, it’ll feed back into your motif to create a comprehensive picture of whatever that motif is.

For example, say you want to write a narrative essay about how your first day in high school helped you establish your identity. You might discuss events like trying to figure out where to sit in the cafeteria, having to describe yourself in five words as an icebreaker in your math class, or being unsure what to do during your lunch break because it’s no longer acceptable to go outside and play during lunch. All of those ideas feed back into the central motif of establishing your identity.

The important thing to remember is that while a narrative essay is typically told chronologically and intended to read like a story, it is not purely for entertainment value. A narrative essay delivers its theme by deliberately weaving the motifs through the events, scenes, and details. While a narrative essay may be entertaining, its primary purpose is to tell a complete story based on a central meaning.

Unlike other essay forms, it is totally okay—even expected—to use first-person narration in narrative essays. If you’re writing a story about yourself, it’s natural to refer to yourself within the essay. It’s also okay to use other perspectives, such as third- or even second-person, but that should only be done if it better serves your motif. Generally speaking, your narrative essay should be in first-person perspective.

Though your motif choices may feel at times like you’re making a point the way you would in an argumentative essay, a narrative essay’s goal is to tell a story, not convince the reader of anything. Your reader should be able to tell what your motif is from reading, but you don’t have to change their mind about anything. If they don’t understand the point you are making, you should consider strengthening the delivery of the events and descriptions that support your motif.

Narrative essays also share some features with analytical essays, in which you derive meaning from a book, film, or other media. But narrative essays work differently—you’re not trying to draw meaning from an existing text, but rather using an event you’ve experienced to convey meaning. In an analytical essay, you examine narrative, whereas in a narrative essay you create narrative.

The structure of a narrative essay is also a bit different than other essays. You’ll generally be getting your point across chronologically as opposed to grouping together specific arguments in paragraphs or sections. To return to the example of an essay discussing your first day of high school and how it impacted the shaping of your identity, it would be weird to put the events out of order, even if not knowing what to do after lunch feels like a stronger idea than choosing where to sit. Instead of organizing to deliver your information based on maximum impact, you’ll be telling your story as it happened, using concrete details to reinforce your theme.

3 Great Narrative Essay Examples

One of the best ways to learn how to write a narrative essay is to look at a great narrative essay sample. Let’s take a look at some truly stellar narrative essay examples and dive into what exactly makes them work so well.

A Ticket to the Fair by David Foster Wallace

Today is Press Day at the Illinois State Fair in Springfield, and I’m supposed to be at the fairgrounds by 9:00 A.M. to get my credentials. I imagine credentials to be a small white card in the band of a fedora. I’ve never been considered press before. My real interest in credentials is getting into rides and shows for free. I’m fresh in from the East Coast, for an East Coast magazine. Why exactly they’re interested in the Illinois State Fair remains unclear to me. I suspect that every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember that about 90 percent of the United States lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropological reporting on something rural and heartlandish. I think they asked me to do this because I grew up here, just a couple hours’ drive from downstate Springfield. I never did go to the state fair, though—I pretty much topped out at the county fair level. Actually, I haven’t been back to Illinois for a long time, and I can’t say I’ve missed it.

Throughout this essay, David Foster Wallace recounts his experience as press at the Illinois State Fair. But it’s clear from this opening that he’s not just reporting on the events exactly as they happened—though that’s also true— but rather making a point about how the East Coast, where he lives and works, thinks about the Midwest.

In his opening paragraph, Wallace states that outright: “Why exactly they’re interested in the Illinois State Fair remains unclear to me. I suspect that every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember that about 90 percent of the United States lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropological reporting on something rural and heartlandish.”

Not every motif needs to be stated this clearly , but in an essay as long as Wallace’s, particularly since the audience for such a piece may feel similarly and forget that such a large portion of the country exists, it’s important to make that point clear.

But Wallace doesn’t just rest on introducing his motif and telling the events exactly as they occurred from there. It’s clear that he selects events that remind us of that idea of East Coast cynicism , such as when he realizes that the Help Me Grow tent is standing on top of fake grass that is killing the real grass beneath, when he realizes the hypocrisy of craving a corn dog when faced with a real, suffering pig, when he’s upset for his friend even though he’s not the one being sexually harassed, and when he witnesses another East Coast person doing something he wouldn’t dare to do.

Wallace is literally telling the audience exactly what happened, complete with dates and timestamps for when each event occurred. But he’s also choosing those events with a purpose—he doesn’t focus on details that don’t serve his motif. That’s why he discusses the experiences of people, how the smells are unappealing to him, and how all the people he meets, in cowboy hats, overalls, or “black spandex that looks like cheesecake leotards,” feel almost alien to him.

All of these details feed back into the throughline of East Coast thinking that Wallace introduces in the first paragraph. He also refers back to it in the essay’s final paragraph, stating:

At last, an overarching theory blooms inside my head: megalopolitan East Coasters’ summer treats and breaks and literally ‘getaways,’ flights-from—from crowds, noise, heat, dirt, the stress of too many sensory choices….The East Coast existential treat is escape from confines and stimuli—quiet, rustic vistas that hold still, turn inward, turn away. Not so in the rural Midwest. Here you’re pretty much away all the time….Something in a Midwesterner sort of actuates , deep down, at a public event….The real spectacle that draws us here is us.

Throughout this journey, Wallace has tried to demonstrate how the East Coast thinks about the Midwest, ultimately concluding that they are captivated by the Midwest’s less stimuli-filled life, but that the real reason they are interested in events like the Illinois State Fair is that they are, in some ways, a means of looking at the East Coast in a new, estranging way.

The reason this works so well is that Wallace has carefully chosen his examples, outlined his motif and themes in the first paragraph, and eventually circled back to the original motif with a clearer understanding of his original point.

When outlining your own narrative essay, try to do the same. Start with a theme, build upon it with examples, and return to it in the end with an even deeper understanding of the original issue. You don’t need this much space to explore a theme, either—as we’ll see in the next example, a strong narrative essay can also be very short.

Death of a Moth by Virginia Woolf

After a time, tired by his dancing apparently, he settled on the window ledge in the sun, and, the queer spectacle being at an end, I forgot about him. Then, looking up, my eye was caught by him. He was trying to resume his dancing, but seemed either so stiff or so awkward that he could only flutter to the bottom of the window-pane; and when he tried to fly across it he failed. Being intent on other matters I watched these futile attempts for a time without thinking, unconsciously waiting for him to resume his flight, as one waits for a machine, that has stopped momentarily, to start again without considering the reason of its failure. After perhaps a seventh attempt he slipped from the wooden ledge and fell, fluttering his wings, on to his back on the window sill. The helplessness of his attitude roused me. It flashed upon me that he was in difficulties; he could no longer raise himself; his legs struggled vainly. But, as I stretched out a pencil, meaning to help him to right himself, it came over me that the failure and awkwardness were the approach of death. I laid the pencil down again.

In this essay, Virginia Woolf explains her encounter with a dying moth. On surface level, this essay is just a recounting of an afternoon in which she watched a moth die—it’s even established in the title. But there’s more to it than that. Though Woolf does not begin her essay with as clear a motif as Wallace, it’s not hard to pick out the evidence she uses to support her point, which is that the experience of this moth is also the human experience.

In the title, Woolf tells us this essay is about death. But in the first paragraph, she seems to mostly be discussing life—the moth is “content with life,” people are working in the fields, and birds are flying. However, she mentions that it is mid-September and that the fields were being plowed. It’s autumn and it’s time for the harvest; the time of year in which many things die.

In this short essay, she chronicles the experience of watching a moth seemingly embody life, then die. Though this essay is literally about a moth, it’s also about a whole lot more than that. After all, moths aren’t the only things that die—Woolf is also reflecting on her own mortality, as well as the mortality of everything around her.

At its core, the essay discusses the push and pull of life and death, not in a way that’s necessarily sad, but in a way that is accepting of both. Woolf begins by setting up the transitional fall season, often associated with things coming to an end, and raises the ideas of pleasure, vitality, and pity.

At one point, Woolf tries to help the dying moth, but reconsiders, as it would interfere with the natural order of the world. The moth’s death is part of the natural order of the world, just like fall, just like her own eventual death.

All these themes are set up in the beginning and explored throughout the essay’s narrative. Though Woolf doesn’t directly state her theme, she reinforces it by choosing a small, isolated event—watching a moth die—and illustrating her point through details.

With this essay, we can see that you don’t need a big, weird, exciting event to discuss an important meaning. Woolf is able to explore complicated ideas in a short essay by being deliberate about what details she includes, just as you can be in your own essays.

Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

On the twenty-ninth of July, in 1943, my father died. On the same day, a few hours later, his last child was born. Over a month before this, while all our energies were concentrated in waiting for these events, there had been, in Detroit, one of the bloodiest race riots of the century. A few hours after my father’s funeral, while he lay in state in the undertaker’s chapel, a race riot broke out in Harlem. On the morning of the third of August, we drove my father to the graveyard through a wilderness of smashed plate glass.

Like Woolf, Baldwin does not lay out his themes in concrete terms—unlike Wallace, there’s no clear sentence that explains what he’ll be talking about. However, you can see the motifs quite clearly: death, fatherhood, struggle, and race.

Throughout the narrative essay, Baldwin discusses the circumstances of his father’s death, including his complicated relationship with his father. By introducing those motifs in the first paragraph, the reader understands that everything discussed in the essay will come back to those core ideas. When Baldwin talks about his experience with a white teacher taking an interest in him and his father’s resistance to that, he is also talking about race and his father’s death. When he talks about his father’s death, he is also talking about his views on race. When he talks about his encounters with segregation and racism, he is talking, in part, about his father.

Because his father was a hard, uncompromising man, Baldwin struggles to reconcile the knowledge that his father was right about many things with his desire to not let that hardness consume him, as well.

Baldwin doesn’t explicitly state any of this, but his writing so often touches on the same motifs that it becomes clear he wants us to think about all these ideas in conversation with one another.

At the end of the essay, Baldwin makes it more clear:

This fight begins, however, in the heart and it had now been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair. This intimation made my heart heavy and, now that my father was irrecoverable, I wished that he had been beside me so that I could have searched his face for the answers which only the future would give me now.

Here, Baldwin ties together the themes and motifs into one clear statement: that he must continue to fight and recognize injustice, especially racial injustice, just as his father did. But unlike his father, he must do it beginning with himself—he must not let himself be closed off to the world as his father was. And yet, he still wishes he had his father for guidance, even as he establishes that he hopes to be a different man than his father.

In this essay, Baldwin loads the front of the essay with his motifs, and, through his narrative, weaves them together into a theme. In the end, he comes to a conclusion that connects all of those things together and leaves the reader with a lasting impression of completion—though the elements may have been initially disparate, in the end everything makes sense.

You can replicate this tactic of introducing seemingly unattached ideas and weaving them together in your own essays. By introducing those motifs, developing them throughout, and bringing them together in the end, you can demonstrate to your reader how all of them are related. However, it’s especially important to be sure that your motifs and clear and consistent throughout your essay so that the conclusion feels earned and consistent—if not, readers may feel mislead.

5 Key Tips for Writing Narrative Essays

Narrative essays can be a lot of fun to write since they’re so heavily based on creativity. But that can also feel intimidating—sometimes it’s easier to have strict guidelines than to have to make it all up yourself. Here are a few tips to keep your narrative essay feeling strong and fresh.

Develop Strong Motifs

Motifs are the foundation of a narrative essay . What are you trying to say? How can you say that using specific symbols or events? Those are your motifs.

In the same way that an argumentative essay’s body should support its thesis, the body of your narrative essay should include motifs that support your theme.

Try to avoid cliches, as these will feel tired to your readers. Instead of roses to symbolize love, try succulents. Instead of the ocean representing some vast, unknowable truth, try the depths of your brother’s bedroom. Keep your language and motifs fresh and your essay will be even stronger!

Use First-Person Perspective

In many essays, you’re expected to remove yourself so that your points stand on their own. Not so in a narrative essay—in this case, you want to make use of your own perspective.

Sometimes a different perspective can make your point even stronger. If you want someone to identify with your point of view, it may be tempting to choose a second-person perspective. However, be sure you really understand the function of second-person; it’s very easy to put a reader off if the narration isn’t expertly deployed.

If you want a little bit of distance, third-person perspective may be okay. But be careful—too much distance and your reader may feel like the narrative lacks truth.

That’s why first-person perspective is the standard. It keeps you, the writer, close to the narrative, reminding the reader that it really happened. And because you really know what happened and how, you’re free to inject your own opinion into the story without it detracting from your point, as it would in a different type of essay.

Stick to the Truth

Your essay should be true. However, this is a creative essay, and it’s okay to embellish a little. Rarely in life do we experience anything with a clear, concrete meaning the way somebody in a book might. If you flub the details a little, it’s okay—just don’t make them up entirely.

Also, nobody expects you to perfectly recall details that may have happened years ago. You may have to reconstruct dialog from your memory and your imagination. That’s okay, again, as long as you aren’t making it up entirely and assigning made-up statements to somebody.

Dialog is a powerful tool. A good conversation can add flavor and interest to a story, as we saw demonstrated in David Foster Wallace’s essay. As previously mentioned, it’s okay to flub it a little, especially because you’re likely writing about an experience you had without knowing that you’d be writing about it later.

However, don’t rely too much on it. Your narrative essay shouldn’t be told through people explaining things to one another; the motif comes through in the details. Dialog can be one of those details, but it shouldn’t be the only one.

Use Sensory Descriptions

Because a narrative essay is a story, you can use sensory details to make your writing more interesting. If you’re describing a particular experience, you can go into detail about things like taste, smell, and hearing in a way that you probably wouldn’t do in any other essay style.

These details can tie into your overall motifs and further your point. Woolf describes in great detail what she sees while watching the moth, giving us the sense that we, too, are watching the moth. In Wallace’s essay, he discusses the sights, sounds, and smells of the Illinois State Fair to help emphasize his point about its strangeness. And in Baldwin’s essay, he describes shattered glass as a “wilderness,” and uses the feelings of his body to describe his mental state.

All these descriptions anchor us not only in the story, but in the motifs and themes as well. One of the tools of a writer is making the reader feel as you felt, and sensory details help you achieve that.

What’s Next?

Looking to brush up on your essay-writing capabilities before the ACT? This guide to ACT English will walk you through some of the best strategies and practice questions to get you prepared!

Part of practicing for the ACT is ensuring your word choice and diction are on point. Check out this guide to some of the most common errors on the ACT English section to be sure that you're not making these common mistakes!

A solid understanding of English principles will help you make an effective point in a narrative essay, and you can get that understanding through taking a rigorous assortment of high school English classes !

Melissa Brinks graduated from the University of Washington in 2014 with a Bachelor's in English with a creative writing emphasis. She has spent several years tutoring K-12 students in many subjects, including in SAT prep, to help them prepare for their college education.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Autobiographies

How to Write a Life Story Essay

Last Updated: May 28, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Alicia Cook . Alicia Cook is a Professional Writer based in Newark, New Jersey. With over 12 years of experience, Alicia specializes in poetry and uses her platform to advocate for families affected by addiction and to fight for breaking the stigma against addiction and mental illness. She holds a BA in English and Journalism from Georgian Court University and an MBA from Saint Peter’s University. Alicia is a bestselling poet with Andrews McMeel Publishing and her work has been featured in numerous media outlets including the NY Post, CNN, USA Today, the HuffPost, the LA Times, American Songwriter Magazine, and Bustle. She was named by Teen Vogue as one of the 10 social media poets to know and her poetry mixtape, “Stuff I’ve Been Feeling Lately” was a finalist in the 2016 Goodreads Choice Awards. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 101,214 times.

A life story essay involves telling the story of your life in a short, nonfiction format. It can also be called an autobiographical essay. In this essay, you will tell a factual story about some element of your life, perhaps for a college application or for a school assignment.

Preparing to Write Your Essay

- If you are writing a personal essay for a college application, it should serve to give the admissions committee a sense of who you are, beyond the basics of your application file. Your transcript, your letters of recommendation, and your resume will provide an overview of your work experience, interests, and academic record. Your essay allows you to make your application unique and individual to you, through your personal story. [2] X Research source

- The essay will also show the admissions committee how well you can write and structure an essay. Your essay should show you can create a meaningful piece of writing that interests your reader, conveys a unique message, and flows well.

- If you are writing a life story for a specific school assignment, such as in a composition course, ask your teacher about the assignment requirements.

- Include important events, such as your birth, your childhood and upbringing, and your adolescence. If family member births, deaths, marriages, and other life moments are important to your story, write those down as well.

- Focus on experiences that made a big impact on you and remain a strong memory. This may be a time where you learned an important life lesson, such as failing a test or watching someone else struggle and succeed, or where you felt an intense feeling or emotion, such as grief over someone’s death or joy over someone’s triumph.

- Have you faced a challenge in your life that you overcame, such as family struggles, health issues, a learning disability, or demanding academics?

- Do you have a story to tell about your cultural or ethnic background, or your family traditions?

- Have you dealt with failure or life obstacles?

- Do you have a unique passion or hobby?

- Have you traveled outside of your community, to another country, city, or area? What did you take away from the experience and how will you carry what you learned into a college setting?

- Remind yourself of your accomplishments by going through your resume. Think about any awards or experiences you would like spotlight in your essay. For example, explaining the story behind your Honor Roll status in high school, or how you worked hard to receive an internship in a prestigious program.

- Remember that your resume or C.V. is there to list off your accomplishments and awards, so your life story shouldn't just rehash them. Instead, use them as a jumping-off place to explain the process behind them, or what they reflect (or do not reflect) about you as a person.

- The New York Times publishes stellar examples of high school life story essays each year. You can read some of them on the NYT website. [8] X Research source

Writing Your Essay

- For example, you may look back at your time in foster care as a child or when you scored your first paying job. Consider how you handled these situations and any life lessons you learned from these lessons. Try to connect past experiences to who you are now, or who you aspire to be in the future.

- Your time in foster care, for example, may have taught you resilience, perseverance and a sense of curiosity around how other families function and live. This could then tie into your application to a Journalism program, as the experience shows you have a persistent nature and a desire to investigate other people’s stories or experiences.

- Certain life story essays have become cliche and familiar to admission committees. Avoid sports injuries stories, such as the time you injured your ankle in a game and had to find a way to persevere. You should also avoid using an overseas trip to a poor, foreign country as the basis for your self transformation. This is a familiar theme that many admission committees will consider cliche and not unique or authentic. [11] X Research source

- Other common, cliche topics to avoid include vacations, "adversity" as an undeveloped theme, or the "journey". [12] X Research source

- Try to phrase your thesis in terms of a lesson learned. For example, “Although growing up in foster care in a troubled neighborhood was challenging and difficult, it taught me that I can be more than my upbringing or my background through hard work, perseverance, and education.”

- You can also phrase your thesis in terms of lessons you have yet to learn, or seek to learn through the program you are applying for. For example, “Growing up surrounded by my mother’s traditional cooking and cultural habits that have been passed down through the generations of my family, I realized I wanted to discover and honor the traditions of other, ancient cultures with a career in archaeology.”

- Both of these thesis statements are good because they tell your readers exactly what to expect in clear detail.

- An anecdote is a very short story that carries moral or symbolic weight. It can be a poetic or powerful way to start your essay and engage your reader right away. You may want to start directly with a retelling of a key past experience or the moment you realized a life lesson.

- For example, you could start with a vivid memory, such as this from an essay that got its author into Harvard Business School: "I first considered applying to Berry College while dangling from a fifty-food Georgia pine tree, encouraging a high school classmate, literally, to make a leap of faith." [15] X Research source This opening line gives a vivid mental picture of what the author was doing at a specific, crucial moment in time and starts off the theme of "leaps of faith" that is carried through the rest of the essay.

- Another great example clearly communicates the author's emotional state from the opening moments: "Through seven-year-old eyes I watched in terror as my mother grimaced in pain." This essay, by a prospective medical school student, goes on to tell about her experience being at her brother's birth and how it shaped her desire to become an OB/GYN. The opening line sets the scene and lets you know immediately what the author was feeling during this important experience. It also resists reader expectations, since it begins with pain but ends in the joy of her brother's birth.

- Avoid using a quotation. This is an extremely cliche way to begin an essay and could put your reader off immediately. If you simply must use a quotation, avoid generic quotes like “Spread your wings and fly” or “There is no ‘I’ in ‘team’”. Choose a quotation that relates directly to your experience or the theme of your essay. This could be a quotation from a poem or piece of writing that speaks to you, moves you, or helped you during a rough time.

- Always use the first person in a personal essay. The essay should be coming from you and should tell the reader directly about your life experiences, with “I” statements.

- For example, avoid something such as “I had a hard time growing up. I was in a bad situation.” You can expand this to be more distinct, but still carry a similar tone and voice. “When I was growing up in foster care, I had difficulties connecting with my foster parents and with my new neighborhood. At the time, I thought I was in a bad situation I would never be able to be free from.”

- For example, consider this statement: "I am a good debater. I am highly motivated and have been a strong leader all through high school." This gives only the barest detail, and does not allow your reader any personal or unique information that will set you apart from the ten billion other essays she has to sift through.

- In contrast, consider this one: "My mother says I'm loud. I say you have to speak up to be heard. As president of my high school's debate team for the past three years, I have learned to show courage even when my heart is pounding in my throat. I have learned to consider the views of people different than myself, and even to argue for them when I passionately disagree. I have learned to lead teams in approaching complicated issues. And, most importantly for a formerly shy young girl, I have found my voice." This example shows personality, uses parallel structure for impact, and gives concrete detail about what the author has learned from her life experience as a debater.

- An example of a passive sentence is: “The cake was eaten by the dog.” The subject (the dog) is not in the expected subject position (first) and is not "doing" the expected action. This is confusing and can often be unclear.

- An example of an active sentence is: “The dog ate the cake.” The subject (the dog) is in the subject position (first), and is doing the expected action. This is much more clear for the reader and is a stronger sentence.

- Lead the reader INTO your story with a powerful beginning, such as an anecdote or a quote.

- Take the reader THROUGH your story with the context and key parts of your experience.

- End with the BEYOND message about how the experience has affected who you are now and who you want to be in college and after college.

Editing Your Essay

- For example, a sentence like “I struggled during my first year of college, feeling overwhelmed by new experiences and new people” is not very strong because it states the obvious and does not distinguish you are unique or singular. Most people struggle and feel overwhelmed during their first year of college. Adjust sentences like this so they appear unique to you.

- For example, consider this: “During my first year of college, I struggled with meeting deadlines and assignments. My previous home life was not very structured or strict, so I had to teach myself discipline and the value of deadlines.” This relates your struggle to something personal and explains how you learned from it.

- It can be difficult to proofread your own work, so reach out to a teacher, a mentor, a family member, or a friend and ask them to read over your essay. They can act as first readers and respond to any proofreading errors, as well as the essay as a whole.

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://education.seattlepi.com/write-thesis-statement-autobiographical-essay-1686.html

- ↑ https://study.com/learn/lesson/autobiography-essay-examples-steps.html

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/fulfillment-any-age/201101/writing-compelling-life-story-in-500-words-or-less

- ↑ Alicia Cook. Professional Writer. Expert Interview. 11 December 2020.

- ↑ https://mycustomessay.com/blog/how-to-write-an-autobiography-essay.html

- ↑ http://www.ahwatukee.com/community_focus/article_c79b33da-09a5-11e3-95a8-001a4bcf887a.html

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/10/your-money/four-stand-out-college-essays-about-money.html

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xY9AdFx0L4s

- ↑ https://www.medina-esc.org/Downloads/Practical%20Advice%20Writing%20College%20App%20Essay.pdf

- ↑ http://www.businessinsider.com/successful-harvard-business-school-essays-2012-11?op=1

- ↑ http://www.grammar-monster.com/glossary/passive_sentences.htm

About This Article

A life story essay is an essay that tells the story of your life in a short, nonfiction format. Start by coming up with a thesis statement, which will help you structure your essay. For example, your thesis could be about the influence of your family's culture on your life or how you've grown from overcoming challenging circumstances. You can include important life events that link to your thesis, like jobs you’ve worked, friendships that have influenced you, or sports competitions you’ve won. Consider starting your essay with an anecdote that introduces your thesis. For instance, if you're writing about your family's culture, you could start by talking about the first festival you went to and how it inspired you. Finish by writing about how the experiences have affected you and who you want to be in the future. For more tips from our Education co-author, including how to edit your essay effectively, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Waitlisted? No Brags. No Updates. Learn About Ivy Coach's Letter of Continued Interest

The Ivy Coach Daily

- College Admissions

- College Essays

- Early Decision / Early Action

- Extracurricular Activities

- Standardized Testing

- The Rankings

October 21, 2016

Life Lessons in College Essays

It’s important to have a life lesson in college essays, right? A great Personal Statement wouldn’t be compelling if it didn’t wrap up with a story about a life lesson learned, right? Maybe it’s about understanding the value of hard work. Maybe it’s about understanding the importance of perseverance and overcoming adversity in pursuit of your goals. Maybe it’s about realizing that all people are, in many ways, more alike than different. These are the kinds of life lessons that make for compelling storytelling not only in the Common Application’s Personal Statement but in the unique supplemental essays for the schools to which students apply, right?

One of these things doesn’t belong in college essays: a life lesson, great storytelling, and colloquial writing. Which one is it, you ask?

No, not right. But the regular readers of our college admissions blog know that the entire introductory paragraph above was one big setup. Life lessons have no place in college admissions essays to highly selective schools. Life lessons are cliche. You pulled your hamstring but nursed your way back from injury to compete in the 100 meter dash again? You may not have won but you tried your best? Cliche. You realized that the folks in Soweto, South Africa are just the same as you and your neighbors in Greenwich, Connecticut? Cliche. You learn about the importance of love and family from your wise grandfather? Cliche.

Life lessons have no place in college essays. Let’s say it again. Life lessons have no place in college essays. When admissions officers are reading hundreds upon hundreds of essays, how many come-from-behind races can they possibly enjoy? The answer is zero. “Full House” was a terrific television show on ABC. And its sequel “Fuller House” is a nice followup on Netflix. For those not familiar with “Full House,” Danny, Jesse, and Joey often imparted life lessons on D.J., Stephanie, Michelle at the end of each episode. But college admissions essays are not episodes of “Full House.” So leave the life lesson out and don’t think twice about it.

You are permitted to use www.ivycoach.com (including the content of the Blog) for your personal, non-commercial use only. You must not copy, download, print, or otherwise distribute the content on our site without the prior written consent of Ivy Coach, Inc.

Related Articles

Using A.I. to Write College Admission Essays

October 13, 2023

Word and Character Limits in College Essays

September 27, 2023

What English Teachers Get Wrong About Writing College Essays

Bragging in College Essays: Is It Ever Okay?

September 26, 2023

What Not to Write: 3 College Essay Topics to Avoid

September 24, 2023

2023-2024 Caltech Supplemental Essay Prompts

September 14, 2023

TOWARD THE CONQUEST OF ADMISSION

If you’re interested in Ivy Coach’s college counseling, fill out our complimentary consultation form and we’ll be in touch.

Fill out our short form for a 20-minute consultation to learn about Ivy Coach’s services.

How to Write a Perfect Narrative Essay (Step-by-Step)

By Status.net Editorial Team on October 17, 2023 — 10 minutes to read

- Understanding a Narrative Essay Part 1

- Typical Narrative Essay Structure Part 2

- Narrative Essay Template Part 3

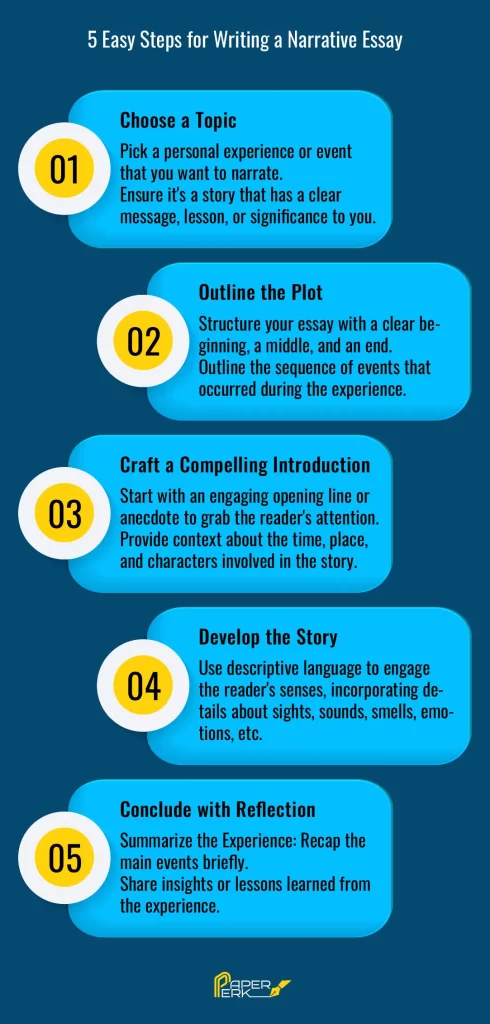

- Step 1. How to Choose Your Narrative Essay Topic Part 4

- Step 2. Planning the Structure Part 5

- Step 3. Crafting an Intriguing Introduction Part 6

- Step 4. Weaving the Narrative Body Part 7

- Step 5. Creating a Conclusion Part 8

- Step 6. Polishing the Essay Part 9

- Step 7. Feedback and Revision Part 10

Part 1 Understanding a Narrative Essay

A narrative essay is a form of writing where you share a personal experience or tell a story to make a point or convey a lesson. Unlike other types of essays, a narrative essay aims to engage your audience by sharing your perspective and taking them on an emotional journey.

- To begin, choose a meaningful topic . Pick a story or experience that had a significant impact on your life, taught you something valuable, or made you see the world differently. You want your readers to learn from your experiences, so choose something that will resonate with others.

- Next, create an outline . Although narrative essays allow for creative storytelling, it’s still helpful to have a roadmap to guide your writing. List the main events, the characters involved, and the settings where the events took place. This will help you ensure that your essay is well-structured and easy to follow.

- When writing your narrative essay, focus on showing, not telling . This means that you should use descriptive language and vivid details to paint a picture in your reader’s mind. For example, instead of stating that it was a rainy day, describe the sound of rain hitting your window, the feeling of cold wetness around you, and the sight of puddles forming around your feet. These sensory details will make your essay more engaging and immersive.

- Another key aspect is developing your characters . Give your readers an insight into the thoughts and emotions of the people in your story. This helps them connect with the story, empathize with the characters, and understand their actions. For instance, if your essay is about a challenging hike you took with a friend, spend some time describing your friend’s personality and how the experience impacted their attitude or feelings.

- Keep the pace interesting . Vary your sentence lengths and structures, and don’t be afraid to use some stylistic devices like dialogue, flashbacks, and metaphors. This adds more depth and dimension to your story, keeping your readers engaged from beginning to end.

Part 2 Typical Narrative Essay Structure

A narrative essay typically follows a three-part structure: introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Introduction: Start with a hook to grab attention and introduce your story. Provide some background to set the stage for the main events.

- Body: Develop your story in detail. Describe scenes, characters, and emotions. Use dialogue when necessary to provide conversational elements.

- Conclusion: Sum up your story, revealing the lesson learned or the moral of the story. Leave your audience with a lasting impression.

Part 3 Narrative Essay Template

- 1. Introduction : Set the scene and introduce the main characters and setting of your story. Use descriptive language to paint a vivid picture for your reader and capture their attention.

- Body 2. Rising Action : Develop the plot by introducing a conflict or challenge that the main character must face. This could be a personal struggle, a difficult decision, or an external obstacle. 3. Climax : This is the turning point of the story, where the conflict reaches its peak and the main character must make a critical decision or take action. 4. Falling Action : Show the consequences of the main character’s decision or action, and how it affects the rest of the story. 5. Resolution : Bring the story to a satisfying conclusion by resolving the conflict and showing how the main character has grown or changed as a result of their experiences.

- 6. Reflection/Conclusion : Reflect on the events of the story and what they mean to you as the writer. This could be a lesson learned, a personal realization, or a message you want to convey to your reader.

Part 4 Step 1. How to Choose Your Narrative Essay Topic

Brainstorming ideas.

Start by jotting down any ideas that pop into your mind. Think about experiences you’ve had, stories you’ve heard, or even books and movies that have resonated with you. Write these ideas down and don’t worry too much about organization yet. It’s all about getting your thoughts on paper.

Once you have a list, review your ideas and identify common themes or connections between them. This process should help you discover potential topics for your narrative essay.

Narrowing Down the Choices

After brainstorming, you’ll likely end up with a few strong contenders for your essay topic. To decide which topic is best, consider the following: